Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Surrogacy is a popular form of assisted reproductive technology of which only gestational form is approved by most of the religious scholars in Iran. Little evidence exists about the Iranian infertile women's viewpoint regarding gestational surrogacy.

AIM:

To assess the viewpoint of Iranian infertile women toward gestational surrogacy.

SETTING AND DESIGN:

This descriptive study was conducted at the infertility clinic of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Iran.

MATERIALS AND METHODS:

The study sample consisted of 238 infertile women who were selected using the eligible sampling method. Data were collected by using a researcher developed questionnaire that included 25 items based on a five-point Likert scale.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS:

Data analysis was conducted by SPSS statistical software using descriptive statistics.

RESULTS:

Viewpoint of 214 women (89.9%) was positive. 36 (15.1%) women considered gestational surrogacy against their religious beliefs; 170 women (71.4%) did not assume the commissioning couple as owners of the baby; 160 women (67.2%) said that children who were born through surrogacy would better not know about it; and 174 women (73.1%) believed that children born through surrogacy will face mental problems.

CONCLUSION:

Iranian infertile women have positive viewpoint regarding the surrogacy. However, to increase the acceptability of surrogacy among infertile women, further efforts are needed.

KEY WORDS: Assisted reproductive technology, infertility, surrogacy

INTRODUCTION

Infertility is defined as 1 year of unprotected intercourse without pregnancy.[1] According to a women and health report published by World Health Organization, data from 47 developing countries (excluding China) shows that in 2004 an estimated 187 million couples were affected by infertility.[2] The result of national population-based study in Iran showed that 8% of Iranian women experience infertility during their reproductive life.[3]

Infertility has been conceptualized emotionally stressful and psychologically threatening experience and reaction to it have been compared with grief. It negatively affects different aspects of couples’ life, which includes, but not limited to, disruptions in couples’ personal life, quality of emotional and sexual relationships, as well as their relationship with co-workers, family, and friends.[4–6] Abedinia et al. reported that 40.8% of infertile women referred to infertility clinic in Tehran, capital city of Iran, were depressed and 86.6% of them were anxious.[7] Similarly, Behdani et al. in another study in Mashad, a metropolis city of Iran, found that infertile women suffer from anxiety (44.1%) and depression (30.4%).[8] Also, Besharat and Hossein-Zadeh Bazargan reported that the mental health of fertile women was better than that of infertile women.[9]

Social transformations as well as medical science advances regarding infertility treatment has resulted in increasing demand of infertility services.[10] Today, advances in assisted reproductive technology (ART) can offer hope to many couples with infertility where, a few years ago, none existed.[11] The need for ART has increased and will probably continue to rise worldwide.[12–14] One of the most popular ART methods is surrogacy.[15,16]

The practice of surrogacy, whereby one woman bears a child for another woman, is one of the most popular methods in the field of ART associated with plenty of controversies.[17] In surrogacy, one woman (surrogate mother) carries a child for other persons (commissioning couples) based on an agreement before conception, requiring the child to be handed over to commissioning couples following birth.[18,19] It takes place in two forms: First, partial or straight surrogacy, where the host is inseminated with the commissioning male's spermatozoa; second, full or host surrogacy, where the embryo is the genetic material of the commissioning couple.[10,19,20] Although surrogacy offers several advantages, this procedure has given rise to some ethical and legal issues.[15] However, gestational surrogacy as a treatment for infertility is being practiced in some well-known medical institutions in Tehran and some other cities in Iran.[21]

One important thing in using ART, such as surrogacy, by infertile couples is that their viewpoint regarding this technology may influence the future legislation for ART methods. Little empirical research has been conducted in Iran to explore the viewpoint of infertile women toward surrogacy. Therefore, the aim of the present study was to assess the Iranian infertile women's viewpoint regarding gestational surrogacy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This descriptive study was conducted in the infertility clinic of Al-Zahra hospital related to Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Iran, the main clinic providing ART services in the northwest of Iran. The study sample consisted of 238 infertile married women with a definite diagnosis of infertility that visited the infertility clinic from March 2009 to September in 2009 and were selected by using the eligible sampling method. All women agreed to participate in our study. None of them had undergone gestational surrogacy before completing the questionnaire. The researcher developed a questionnaire consisted of three sections, which assesses demographic data, maternal history, and the viewpoint of the infertile women. The third section included 23 items considering participants’ viewpoint in five domains, covering legal and religious issues (7 items), conditions for the use of surrogacy (5 items), children born through surrogacy (5 items), surrogate mother (2 items), and tendency to use surrogacy (4 items). Most of these items were derived from previous relevant studies;[5,12,17,18,22] however, some items were added by researchers according to their experience and considering cultural issues. Each item was rated based on a five-point Likert scale, with 1 = ‘completely disagree’ and 5 = ‘completely agree’. The scores ranged from 25 to 125; the higher scores represented positive viewpoint regarding gestational surrogacy. Scores from 25 to 75 were considered as negative viewpoint, and scores greater than and equal to 76 were considered as positive viewpoint. In each item, scores 1–3 were considered as ‘agree’, and scores 3.01–5 were considered as ‘disagree’.

The validity of the prepared questionnaire has been established by content validity for which 15 academic members of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences revised the questionnaire. After receiving the academic members’ comments, the questionnaire was edited. The test-retest reliability of the questionnaire was established by Cronbach's alpha coefficient (0.89) following a pilot study on a sample of 25 infertile women.

Two of the researchers were involved in data collection from the infertility clinic. Everyday before data collection, the necessary information about gestational surrogacy was given to all study subjects. Literate subjects filled out the questionnaire and only in the case of the need for guidance were they helped out, but for illiterate subjects and subjects with a lesser level of education the questionnaires were filled out by interviewers.

The ethics committee of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences approved the study. Participation in the study was voluntary and informed consent was obtained from all respondents before enrollment in the study.

Statistical analyses were performed using the software Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS), version 17.0. Descriptive statistics, including frequencies, mean, and standard deviation, were considered for analyzing the data.

RESULTS

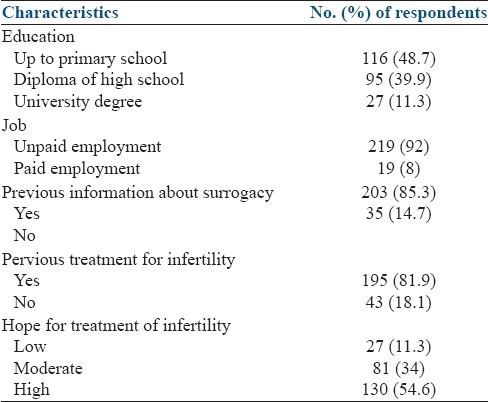

All participants were Shiite Muslim, and the mean age of 238 infertile women was 26.9 ± 5.8 years. The mean of their marriage age was 20.3 ± 5.2 years, and the mean of the infertility period was 6.6 ± 4.9 years. Other demographic characteristics and the maternal history of participants are reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of infertile women

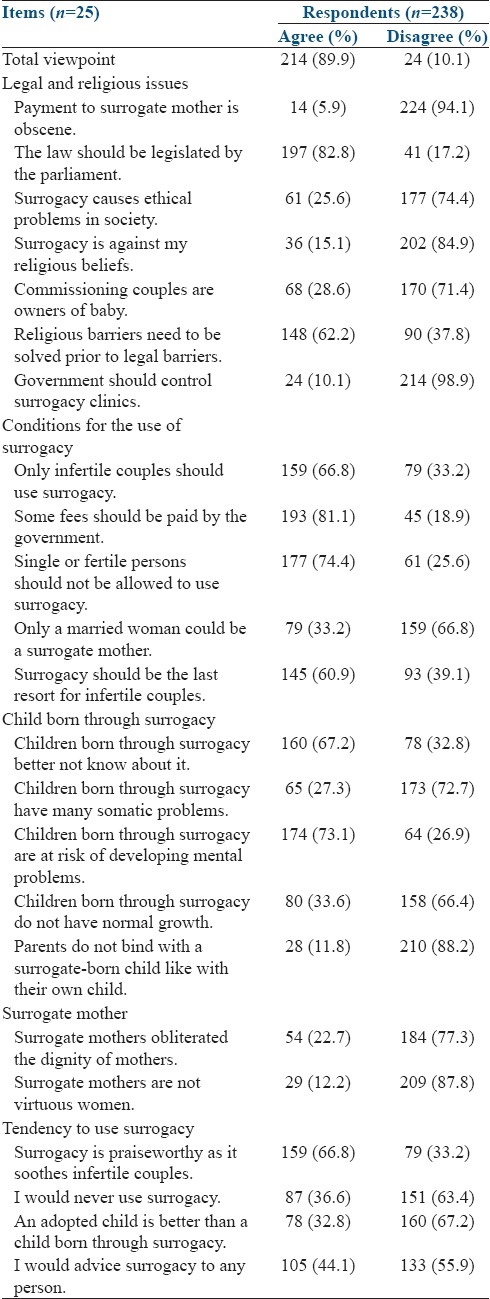

Infertile women's responses to each item of questionnaire and their overall viewpoint are presented in Table 2. As can be seen in Table 2, 214 women (89.9%) have positive viewpoint about gestational surrogacy.

Table 2.

Attitudes of study participants toward gestational surrogacy

DISCUSSION

The results of the present study showed that 89.9% of the infertile women had positive viewpoint toward gestational surrogacy. In a similar study, which is the only published study in this field in Iran, Sohrabvand and Jafarabadi reported contradictory results, in which 95% of the infertile couples in Tehran had negative viewpoint toward gestational surrogacy. However, they assessed the knowledge and attitude of infertile couples about all ART methods with a few questions without considering all aspects of couples’ attitude.[22] It sounds that infertile women's attitudes toward surrogacy practice have changed over the next few years. In other words, the popularity of surrogacy as the ART method might be increasing in Iran. The results of some studies that have been performed in other countries show negative public attitudes toward this method. In a similar study from a mainly Muslim country, Turkey, Kilic et al. reported that only 24% of Turkish infertile women had a positive attitude regarding gestational surrogacy.[18] Poote and Van den Akker revealed that the majority of British women had a negative attitude toward surrogacy.[5] Similarly, Stöbel-Richter et al. found that only 43.7% of German respondents have positive attitude toward surrogacy and approved this method less than other ART methods.[23] It should be noted that attitudes toward infertility and the treatment services can be affected by religious and cultural beliefs and values as well as ethical and legal factors.[18] Acceptability of surrogacy may be different among different cultural and religious groups.[24] We expected that in the present study many of the infertile women had a positive viewpoint toward surrogacy, because we only assessed the viewpoint of infertile women regarding gestational surrogacy. The results might be different if we had investigated public's opinion or infertile women's viewpoint that decided not to use the infertility clinic services or chose to use traditional treatments. In general, the viewpoint toward ART methods in which the children are genetically related to both of their parents is more positive than that toward other methods.[25]

Regarding legal aspect of gestational surrogacy, most infertile women agreed with the activity of institutions in the field of surrogacy and surrogacy laws. Most of them opposed to paying money to surrogate mothers. Similarly, Jadva et al. concluded that only 3% of British surrogate mothers considered money as their main motivation for accepting surrogacy.[17] It should be noted that due to the absence of clear surrogacy laws, most Iranian women accept to be surrogate mothers because of the money. However, many of the respondents did not know commissioning couples as the owner of children born through gestational surrogacy. It is possibly related to effects of pregnancy in creating a sense of motherhood. Qualitative research is needed to better explain the rationale behind this perception.

Concerning religious issues, results showed that most women considered gestational surrogacy with no conflict with religious and moral issues. This perception is likely due to the fact that all the partisans were Shiite and surrogacy has been approved by Shiite scholars.[21] It seems that religion scholars have an important role in improving acceptability of ART methods such as gestational surrogacy. A significant percentage of these women believed that religious problems should be resolved before the legal barriers. It should be noted that this viewpoint might be due to lack of awareness. While most Sunni scholars are opposed to surrogacy, Shitte scholars often agree with gestational surrogacy if done for legally married couples.[21] These results indicate the need for further informing of community on religious aspects of surrogacy.

In conditions of surrogacy application, most of these infertile women accepted surrogacy only for infertile couples. Also, participants believed that married women should not be a surrogate mother. In other words, 60.9% of infertile women believed that surrogacy should be used as the last method of ART. Genuis et al. showed that 74% of American people believed that the surrogacy should be used only for therapeutic purposes and only for married infertile couples.[24]

Regarding attitude toward children born through surrogacy, the infertile women had a positive viewpoint toward these children and believed that it is better these children would not know this matter. Although many of these women believed that these children may face mental problems, it is not clear why they believed that these children are at risk of psychological problems. A possible reason for this viewpoint is that they believed the children's knowledge about surrogacy may associate with a devastating impact on their mental health. This result is different with the results of studies conducted in Western countries; Jadva et al. found that British surrogate mothers believed that it is better that children born through surrogacy better be aware of it.[17] Also, Genuis et al. (1993) reported that most American people believed that children born through this method should be informed about it.[24] Concerns about the health of children born through surrogacy and other ART methods always exist. However, results of many studies have shown that children born through surrogacy are healthy.[26–28]

Regarding viewpoint on surrogate mothers, most of the infertile women considered them chaste and had a positive viewpoint toward them. The results of the study of Kilic et al. showed that 58.3% of Turkish infertile women who agreed with surrogacy approved only their sisters, family members, and friends as a surrogate mother.[18] Also, Stern et al. declared that 89.5% of respondents in United States had accepted only their family and friends as a surrogate mother.[29] Fischer and Gillman reported that surrogate mothers were not different from other women in social support, quality of attachment, and attitude toward pregnancy.[30]

Regarding tendency to use surrogacy, the infertile women believed that surrogacy is better than adoption or not having children. However, 43.1% of the women expressed that they would not advice surrogacy to other women. This view is consistent with their view of using surrogacy as a last ART method. Kilic et al. reported that 25.6% of Turkish infertile women have no tendency to use any form of ART methods, 59.6% accepted the adoption, and only 24% accepted the gestational surrogacy.[18] Consistently, the results of the study of Baykal et al. also showed that only 15.1% of Turkish infertile women confirm surrogacy.[31] The facts that Turkey like Iran is mainly a Muslim country and most of the Turkish people are Sunni Muslims[32] and as we had already discussed that Sunni scholars do not approve surrogacy partially explain a negative attitude toward surrogacy in this country. However, these results are not consistent with the results of the present study. We think that due to the impact of cultural, social, religious, and economic factors on viewpoint toward surrogacy, it is predictable to obtain different results from various countries.

Although the infertile women had a positive viewpoint regarding gestational surrogacy, a significant percentage of them believed that gestational surrogacy is against sharia (the sacred law of Islam) and did not accept the commissioning couples as owners of child. In general, increasing acceptability and implementation of gestational surrogacy in community need further efforts. Increasing public awareness about this fact that surrogacy provides infertile women an opportunity to have their genetic child may improve acceptance of commissioning couples as owners of a surrogate child in the society. Using media to increase the awareness of public about various aspects of gestational surrogacy, particularly the religious and legal aspects and availability of results of studies conducted about children born through this method to public, is suggested. Also, lawmakers should try to pass more legislation about surrogacy.

This study has some limitations that should be considered when using the results of the study. First, the infertile women were selected with the eligible sampling method. Second, the data were gathered with the self-report of infertile women. Third, this study had just assessed the viewpoint of infertile women and did not assess fertile women's viewpoint about gestational surrogacy. Fourth, this study did not assess the viewpoint of the husbands of infertile women. This issue is particularly important in Middle Eastern cultures where men often make health-related decisions in the family. Furthermore, stigma against surrogate mothers, children born through surrogacy, and the commissioning couples impedes applicability of surrogacy. The viewpoint of public about the gestational surrogacy and other forms of ART methods should be investigated. Culturally competent interventions to reduce the related stigma against surrogacy may improve the acceptability of this method.

Acknowledgments

This study has been done by the scientific and financial support of the ethics and medical history research center of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences. We thank all the women who participated in this study.

Footnotes

Source of Support: The ethics and medical history research center of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Berek JS, Novak E. 14th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2011. Berek and Novak's gynecology. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Woman and health: Today's evidence, tomorrow's agenda. World Health Organization. 2009. [Last cited on 2011 Jun 05]. Available from: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2009/9789241563857_eng.pdf .

- 3.Safarinejad MR. Infertility among couples in a population based study in Iran: Prevalence and associated risk factors. Int J Androl. 2008;31:303–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2605.2007.00764.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peterson BD, Pirritano M, Christensen U, Schmidt L. The impact of partner coping in couples experiencing infertility. Hum Reprod. 2008;23:1128–37. doi: 10.1093/humrep/den067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Poote AE, Van den Akker OB. British women's attitudes to surrogacy. Hum Reprod. 2009;24:139–45. doi: 10.1093/humrep/den338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schmidt1 L, Christensen U, Holstein BE. The social epidemiology of coping with infertility. Hum Reprod. 2005;20:1044–52. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abedinia N, Ramazanzadeh f, Aghssa MM. The relationship between anxiety and depression with duration of infertility. Payeh. 2003;2:253–8. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Behdani F, Mousavifar N, Hobrani P, Soltanifar A, Mohammadnezhad M. Anxiety and mood disorders in infertile women referred to Montaserie infertility clinic in Mashhad. Iran J Obstet, Gynecol Infertil. 2008;11:15–23. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Besharat MA, Hossein-Zadeh Bazargan R. A comparative study of fertile and infertile women's mental health and sexual problems. Iran J Psychiatry Clin Psycholo. 2006;12:146–53. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Callman J. Surrogacy-a case for normalization. Hum Reprod. 1999;14:277–8. doi: 10.1093/humrep/14.2.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gardner DK, Weissman A, Howles CM, Shoham Z. 1st ed. London: Informa Healthcare; 2001. Textbook of assisted reproductive techniques: Laboratory and clinical perspectives. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Minai J, Suzuki K, Takeda Y, Hoshi K, Yamagata Z. There are gender differences in attitudes toward surrogacy when information on this technique is provided. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2007;132:193–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2006.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Andersen AN, Goossens V, Gianaroli L, Felberbaum R, de Mouzon J, Nygren KG. Assisted reproductive technology in Europe, 2003.Results generated from European registers by ESHRE. Hum Reprod. 2007;22:1513–25. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dem053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang Y, Dean J, Badgery-Parker T, Sullivan E. Assisted reproduction technology in Australia and New Zealand 2006. [Last Cited on 2011 Jun 07];Australian Institute of Health and Welfare National Perinatal Statistics Unit (2008) Available at: http://www.preru.unsw.edu.au/PRERUWeb.nsf/resources/ART_2005_06/$file/art12+web+tables.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 15.Suzuki K, Hoshi K, Minai J, Yanaihara T, Takeda Y, Yamagata Z. Analysis of national representative opinion surveys concerning gestational surrogacy in Japan. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2006;126:39–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2005.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brinsden PR. Gestational surrogacy. Hum Reprod Update. 2003;9:483–91. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmg033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jadva V, Murray C, Lycett E, MacCallum F, Golombok S. Surrogacy: The experiences of surrogate mothers. Hum Reprod. 2003;18:2196–204. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deg397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kilic S, Ucar M, Yaren H, Gulec M, Atac A, Demirel F, et al. Determination of the attitudes of Turkish infertile women toward surrogacy and oocyte donation. Pak J Med Sci. 2009;25:36–40. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sills ES, Healy CM. Building Irish families through surrogacy: Medical and judicial issues for the advanced reproductive technologies. Reprod Health. 2008;5:9. doi: 10.1186/1742-4755-5-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reilly DR. Surrogate pregnancy: A guide for Canadian prenatal health care providers. CMAJ. 2007;176:483–5. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.060696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aramesh K. Iran's experience with surrogate motherhood: An Islamic view and ethical concerns. J Med Ethics. 2009;35:320–2. doi: 10.1136/jme.2008.027763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sohrabvand F, Jafarabadi M. Knowledge and attitudes of infertile couples about assisted reproductive technology. Iran J Reprod Med. 2005;3:90–4. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stöbel-Richter Y, Goldschmidt S, Brähler E, Weidner K, Beutel M. Egg donation, surrogate mothering, and cloning: Attitudes of men and women in Germany based on a representative survey. Fertil Steril. 2009;92:124–30. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Genuis SJ, Chang WC, Genuis SK. Public attitudes in Edmonton toward assisted reproductive technology. CMAJ. 1993;149:153–61. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Halman LJ, Abbey A, Andrews FM. Attitudes about infertility interventions among fertile and infertile couples. Am J Public Health. 1992;82:191–4. doi: 10.2105/ajph.82.2.191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Golombok S, Murray C, Jadva V, MacCallum F, Lycett E. Families created through surrogacy arrangements: Parent-child relationships in the 1st year of life. Dev Psychol. 2004;40:400–11. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.40.3.400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Serafini P. Outcome and follow-up of children born after IVF-surrogacy. Hum Reprod Update. 2001;7:23–7. doi: 10.1093/humupd/7.1.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Golombok S, MacCallum F, Murray C, Lycett E, Jadva V. Surrogacy families: Parental functioning, parent-child relationships and children's psychological development at age 2. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2006;47:213–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01453.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stern JE, Cramer CP, Garrod A, Green RM. Attitudes on access to services at assisted reproductive technology clinics: Comparisons with clinic policy. Fertil Steril. 2002;77:537–41. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(01)03208-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fischer S, Gillman I. Surrogate motherhood: Attachment, attitudes and social support. Psychiatry. 1991;54:13–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baykal B, Korkmaz C, Ceyhan ST, Goktolga U, Baser I. Opinions of infertile Turkish women on gamete donation and gestational surrogacy. Fertil Steril. 2008;89:817–22. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chapin H. Washington: Kissinger Publishing; 1995. Federal Research Division. Turkey: A country study. [Google Scholar]