Abstract

Aims:

The aim of this study was to report the incidence of retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) and the contribution of various risk factors to ROP in the south-western region of Iran.

Material and Methods:

This cross-sectional case-control series reviewed all low birth weight (LBW, ≤2000 g) neonates and/or neonates less than 32 weeks gestational age who had been hospitalized in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit from 2006 to 2010. The cohort was divided into infants without ROP (nonROP group) and infants with ROP (ROP group). Infants were first examined by a group of pediatric ophthalmologists 6 weeks after delivery, and then were followed every 1-2 weeks until death, discharge or complete retinal avascularization. If an infant developed ROP, further examinations were performed based on the Early Treatment for Retinopathy of Prematurity Study protocol. Demographic data, medical treatment, and ophthalmic disorders were all statistically analyzed.

Results:

A total of 576 infants met the criteria for evaluation. Of 576 total patients, 183 infants (32%) (88 males, 95 females) had ROP. There were significant differences between groups in gestational age, body weight, and duration of oxygen administration, and sepsis (P<0.05). Male/female ratio, single and multiple births, and jaundice, phototherapy, and blood transfusion were not significant. The majority of ROP was stage I or II (137, 74.8%). Stage III or greater developed in 46 infants (25.1%) [Note: The ocular history and ocular outcomes are not risk factors.]

Conclusions:

The incidence of ROP in this study is higher than that in other parts of the world. Awareness and knowledge of ROP and its relative risks need to be reinforced in ophthalmologists and other health practitioners.

Keywords: Incidence, Prematurity, Retinopathy, Risk Factors

INTRODUCTION

Retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) is an ocular disorder involving vascular proliferation in premature infants.1 ROP affects motor, lingual, mental, and social development of affected individuals.2,3 Neovascularization in the retina due to ROP is similar to retinopathies, such as diabetic retinopathy.4,5 The incidence of ROP varies considerably from country to country depending on the economy, social conditions, and the quality of the infant health care system.6–8 Previous studies have reported an increase in the incidence of blindness, visual loss, and impairment due to ROP.9 For example, Sri Lanka,10 Lithuania,11 and Thailand12 have all reported an increase in the incidence of ROP.

An increased incidence of ROP as the body weight of an infant decreases has been previously reported.13–15 For example 7.6% of infants weighing 1500 g had ROP13 whereas 81% of infants weighing less than 1000 g had ROP.14 The pathogenesis of retinopathy of prematurity is a two-phase event: in phase I, increased oxygen in the retina causes a decrease in vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). In phase II, decreased oxygen in the retina causes an increase in VEGF with subsequent neovascularization.5 Thus, oxygen therapy plays an important role in the development of ROP in premature infants.16 It is well-known that preterm babies of low gestational age are more likely to develop ROP and that clinical conditions of patients of low gestational age differ from those of more mature infants.17,18 This study evaluates the contribution of various risk factors to ROP and reports the incidence of ROP in a southwest region of Iran.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This cross-sectional case-control study reviewed ROP in all low birth weight neonates (LBW, ≤2000 g) and/or neonates who were less than 32 weeks gestational age and were hospitalized from January 2006 to July 2010 at the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU) at all educational Hospitals in Khuzestan province, Ahvaz, Iran. The study was approved by the University Hospital and Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences Ethics Committees, and all subjects guardians, granted informed consent to participate. If an infant developed ROP, informed consent was obtained from the parents for further examination based on the Early Treatment for Retinopathy of Prematurity (ETROP) Study protocol.19,20 Briefly, when prethreshold ROP developed, a risk determination was performed using the computerized risk model, RM-ROP2.21 Data were entered into computerized forms.

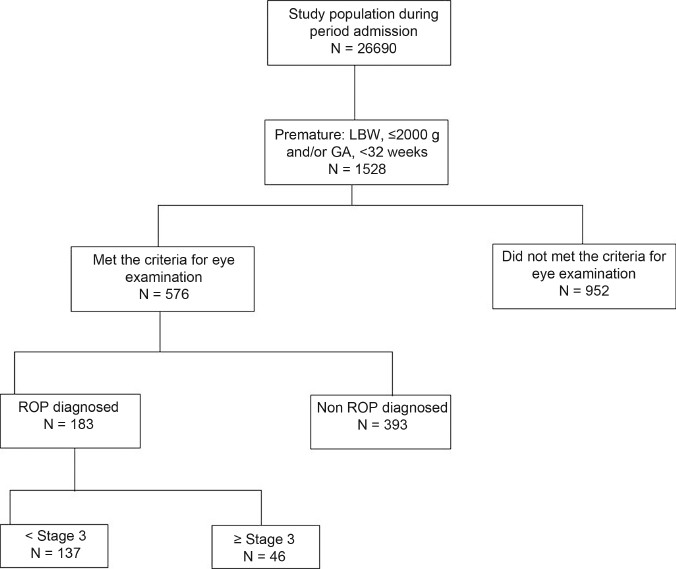

The cohort distribution in this study is illustrated in Figure 1. The gestational age was determined by either the last menstrual period or ultrasound and confirmed with neonatal examination. Surfactant was given to infants who met clinical and radiologic criteria for respiratory distress syndrome as a rescue treatment within 2-6 hours of life. Subjects were grouped according to the presence (ROP group) or absence of ROP (non-ROP group).

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the cohort distribution of infants with and without retinopathy of prematurity in south-western Iran from 2006 to 2010

Exclusion criteria were fatal systemic anomaly, unilateral or bilateral retinal or choroidal disease (or than ROP), a media opacity precluding fundus visualization (e.g., cataract). Infants were also excluded if a neonatologist considered inclusion in the study would unduly challenge the infant, or there was refusal of initial consent or refusal of subsequent evaluation.

All subjects were initially examined by pediatric ophthalmologists 6 weeks after delivery followed by eye examinations every 1-2 weeks until death, discharge or complete retinal vascularization. All infants were kept NPO for 3 hours. For fundus examination, the pupils were dilated with 0.25% cyclopentolate or 0.5% tropicamide (in cases when cyclopentolate was unavailable) and 2.5% phenylephrine, the infant was swaddled, and the indirect ophthalmoscopy was performed with a 30 diopter aspheric lens. In some cases, an infant eye speculum and scleral indentation were used to view the retinal periphery. ROP classification was based on the International Classification of Retinopathy of PrematurityRevisited.22

All statistical analyses were performed with SSPS software (SPSS 13.0 for Windows, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The mean Incidence of ROP was calculated for both groups. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed to analyze continuous variables between groups, and the chi-square test was used to compare categorical variables. The multiple logistic analyses were performed. The results were considered significant for P<0.05, with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI).

RESULTS

A total of 576 infants were included in this study and underwent full ophthalmic examination. Table 1 presents demographic data, and the risk factors introduced by medical intervention for both groups: oxygen duration, sepsis, jaundice, phototherapy, transfusion. There were 393 infants (38%) (212 males, 181 females) in the non-ROP group, and 183 infants (32%) (88 males, 95 females) in the ROP group.

Table 1.

Comparison of demographics, medical conditions, medical therapy, ophthalmic disorders among neonates with or without retinopathy of prematurity

The ROP group underwent a statistically longer periods of oxygen therapy compared to the non-ROP group (P =0.001) [Table 1]. Oxygenation methods included an oxygen hood in 52% of the cases, the nasal method in 14% of the cases, an oxygen mask in 2% of the cases, a ventilator in 5% of the cases, and a combination of hood and nasal methods in 13% of the cases and a combination of hood, oxygen mask, and nasal methods in 2% of entire cohort cases.

The observed risk factors were subjected to multiple logistic regression analysis [Table 2]. Infants with lower birth weight and gestational age were more likely at risk of ROP (OR, 0.52 and 0.92; P< 0.001, respectively). Other significantly increased odds ratios included sepsis (OR, 2.85; P<0.001), and oxygen therapy (OR, 1.51; P< 0.001) [Table 2].

Table 2.

Regression analysis of risk factors for retinopathy of prematurity

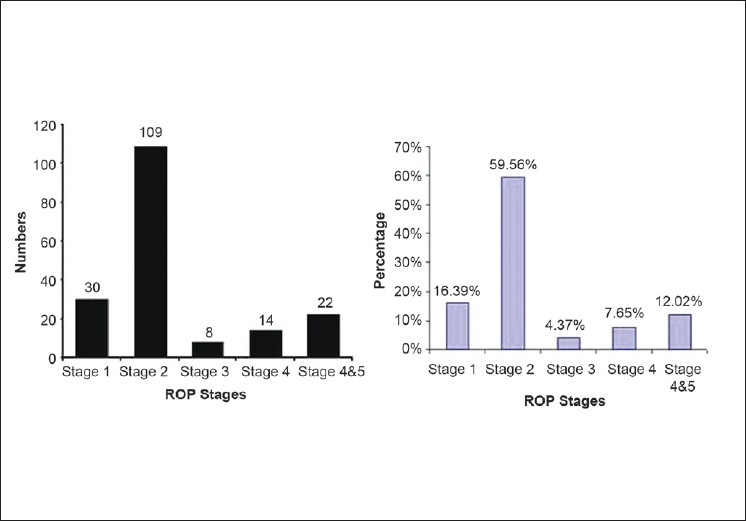

The majority of ROP was stage I or II (137, 74.8%). Stage III or greater developed in 46 infants (25.1%). The various stages of ROP diagnosed in this study and their distribution are presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

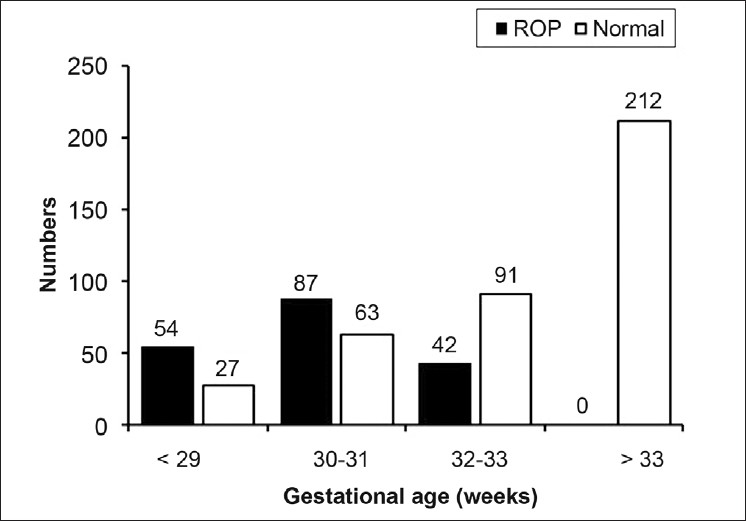

The distribution of gestational ages of infants with and without retinopathy of prematurity in south-western Iran from 2006 to 2010

The mean gestational age of the non-ROP group was significantly higher than that of the ROP group (should give these two means) (P = 0.019) [Table 1, Figure 3]. The ROP group had statistically significant lower mean body weight than the non-ROP group (723 ± 134 vs. 1428 ± 300, P = 0.001) [Table 1].

Figure 3.

The numbers of the different stages of ROP of infants with and without retinopathy of prematurity in south-western Iran from 2006 to 2010

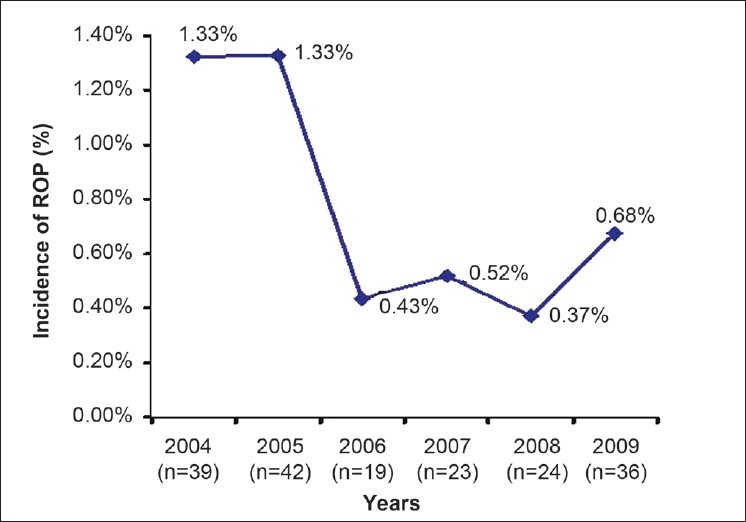

The incidence of ROP changed in the neonatal care units during the time course of the study. In spite of the increase in the population at risk, the incidence showed a major decrease from 2006 to 2008 and a minor change after 2008 [Figure 4]. The incidence of ROP in Khuzestan province, Iran, with a population of 4.3 million, was 32% in premature infants less than or equal to 2000 g birth weight and 32 weeks gestational age at birth.

Figure 4.

Incidence of retinopathy of prematurity of infants with and without retinopathy of prematurity in southwestern Iran from 2006 to 2010

DISCUSSION

We found that 183 premature newborn had ROP out of a total 576 infants. The incidence of ROP in Iran during 2003-2007 was 34.5%.23–25 The incidence reported in the current study (32% from 2006-2010) is about the same as in other regions of Iran over approximately the same time period.23–25

The majority of previous studies have reported the incidence of ROP in infants below 26 weeks gestational age and birth weight of 1000 g.26–29 The current study found only 54 (30%) cases of ROP cases were less than of equal to 29-week gestational age and 87 (48%) cases were 30-31 weeks gestational age, and 42 (22%) cases were greater than or equal to 32 weeks gesationalage. In infants over 1000 g, the incidence of ROP varies from 7.6% to 46.9%.13 Note: in the current study, give correct numbers for 1000 g, example 11 (6%) cases with ROP were less than 1000 g at birth. The low rate of cases less than 1000 g in the current study could be due to a number of factors. One factor is the inadequate nursery and health care systems for premature infants resulting in greater mortality of infants less than 1000 g who are at a greater risk of ROP. Another factor is the lack of follow-up by the parents despite an aggressive approach at educating them on the necessity of a visual examination. Lastly a poor referral system may also compound the low presentation rate of infants less than 1000 g.

The mean gestational age was clearly different between the two groups. Additionally, low gestational age is associated with the presence of ROP, especially gestational age below 28 weeks. Previous studies have documented an association between low-weight infants and ROP.30–32 Our study concurs, as documented by the statistically significantly lower birth weight of infants with ROP (P=0.001). We were also able to show an association with sepsis and the presence of ROP. In the current study, risk factors for ROP including blood transfusion, jaundice, and phototherapy which concur with previous studies were not found to be significantly associated with ROP. The incidence of ROP in the current study (36%) was fairly in agreement with the reported values in countries such as such as China (27%),33 Brazil (18.2%),34 and Saudi Arabia (56%),35 The role of the genetic, social, economic, nutritional factors in ROP should be the focus of future studies in this region of Iran. Limitations of our study include poor patient follow-up, high mortality rate in infants under 1000 g and 28 weeks gestational age, and the lack of comprehensive records. Also it should be noted that 4 weeks postnatal age or 31 weeks postmenstrual age is recommended for the initial ophthalmic examination; however we examined infants at 6 weeks after birth. This may also have affected the outcomes of this study.

In summary, incidence of ROP in the current study indicates there is an urgent need for better care of preterm and low birth weight infants in south-western region of Iran. Health professional such as neonatologists and ophthalmologists require education on the risk factors of ROP and a public education campaign is required for the general population.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors want to thank Seyed Mahmmod Latifi, Dr. Yazdi, Dr. Borna, Dr. Samaeili, Miss Saidi, Miss Mirzaei for their contribution and guidance in the research and manuscript preparation.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Research deputy of Ahwaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.VanStone W. Retinopathy of prematurity: An example of a successful screening program. Neonatal Netw. 2010;29:15–21. doi: 10.1891/0730-0832.29.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hellström A, Engström E, Hård AL, Albertsson-Wikland K, Carlsson B, Niklasson A, et al. Postnatal serum insulin-like growth factor I deficiency is associated with retinopathy of prematurity and other complications of premature birth. Pediatrics. 2003;112:1016–20. doi: 10.1542/peds.112.5.1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Quiram PA, Capone A., Jr Current understanding and management of retinopathy of prematurity. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2007;18:228–34. doi: 10.1097/ICU.0b013e3281107fd3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Akula JD, Favazza TL, Mocko JA, Benador IY, Asturias AL, Kleinman MS, et al. The anatomy of the rat eye with oxygen-induced retinopathy. Doc Ophthalmol. 2010;120:41–50. doi: 10.1007/s10633-009-9198-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sola A, Rogido MR, Deulofeut R. Oxygen as a neonatal health hazard: Call for détente in clinical practice. Acta Paediatr. 2007;96:801–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2007.00287.x. Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fortes Filho JB, Eckert GU, Valiatti FB, da Costa MC, Bonomo PP, Procianoy RS. Prevalence of retinopathy of prematurity: An institutional cross-sectional study of preterm infants in Brazil. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2009;26:216–20. doi: 10.1590/s1020-49892009000900005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shah VA, Yeo CL, Ling YL, Ho LY. Incidence, risk factors of retinopathy of prematurity among very low birth weight infants in Singapore. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2005;34:169–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Delport SD, Swanepoel JC, Odendaal PJ, Roux P. Incidence of retinopathy of prematurity in very-low-birth-weight infants born at Kalafong Hospital, Pretoria. S Afr Med J. 2002;92:986–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tompkins C. A sudden rise in the prevalence of retinopathy of prematurity blindness? Pediatrics. 2001;108:526. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rawoof UH. A situation analysis to provide information for developing a screening and treatment programme for retinopathy of prematurity in Sri Lanka. Community Eye Health. 2007;20:12. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kocur I, Resnikoff S, Foster A International study group. Eye healthcare services in Eastern Europe: Part 2:Vitreoretinal surgical services. Br J Ophthalmol. 2002;86:851–3. doi: 10.1136/bjo.86.8.851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Trinavarat A, Atchaneeyasakul LO, Udompunturak S. Applicability of American and British criteria for screening of the retinopathy of prematurity in Thailand. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2004;48:50–3. doi: 10.1007/s10384-003-0014-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chiang MF, Arons RR, Flynn JT, Starren JB. Incidence of retinopathy of prematurity from 1996 to 2000: Analysis of a comprehensive New York state patient database. Ophthalmology. 2004;111:1317–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2003.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fledelius HC. Central nervous system damage and retinopathy of prematurity: An ophthalmic follow-up of prematures born in 1982-84. Acta Paediatr. 1996;85:1186–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1996.tb18226.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Good WV, Hardy RJ, Dobson V, Palmer EA, Phelps DL, Quintos M, et al. The incidence and course of retinopathy of prematurity: Findings from the early treatment for retinopathy of prematurity study. Pediatrics. 2005;116:15–23. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mechoulam H, Pierce EA. Retinopathy of prematurity: Molecular pathology and therapeutic strategies. Am J Pharmacogenomics. 2003;3:261–77. doi: 10.2165/00129785-200303040-00004. Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brownfoot FC, Crowther CA, Middleton P. Different corticosteroids and regimens for accelerating fetal lung maturation for women at risk of preterm birth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;4:CD006764. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006764.pub2. Review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Effect of corticosteroids for fetal maturation on perinatal outcomes. NIH Consensus development panel on the effect of corticosteroids for fetal maturation on perinatal outcomes. JAMA. 1995;273:413–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.1995.03520290065031. Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Early Treatment for Retinopathy of Prematurity Cooperative Group. Manual of Procedures. Springfield, VA: National Technical Information Service; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hardy RJ, Good WV, Dobson V, Palmer EA, Phelps DL, Quintos M, et al. Multicenter trial of early treatment for retinopathy of prematurity: Study design. Control Clin Trials. 2004;25:311–25. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2004.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hardy RJ, Palmer EA, Dobson V, Summers CG, Phelps DL, Quinn GE, et al. Risk analysis of prethreshold retinopathy of prematurity. Arch Ophthalmol. 2003;121:1697–701. doi: 10.1001/archopht.121.12.1697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.International Committee for the Classification of Retinopathy of Prematurity. The International Classification of Retinopathy of Prematurity revisited. Arch Ophthalmol. 2005;123:991–9. doi: 10.1001/archopht.123.7.991. Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Karkhaneh R, RiaziEsfahani M, Ghojezade L, Kadivar M, Nayeri F, Chams H, et al. Incidence and risk factors of retinopathy of prematurity. Bina J Ophthalmol. 2005;11:81–90. [Google Scholar]

- 24.RiaziEsfahani M, Karkhane R, Shokravi N. Assessment of retinopathy of prematurity among 150 premature neonates in Farabi Eye Hospital. Acta Med Iranica. 2001;39:35–8. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Karkhaneh R, Mousavi SZ, Riazi-Esfahani M, Ebrahimzadeh SA, Roohipoor R, Kadivar M. Incidence and risk factors of retinopathy of prematurity in a tertiary eye hospital in Tehran. Br J Ophthalmol. 2008;92:1446–9. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2008.145136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fischer N, Steurer MA, Adams M, Berger TM Swiss Neonatal Network. Survival rates of extremely preterm infants (gestational age <26 weeks) in Switzerland: Impact of the Swiss guidelines for the care of infants born at the limit of viability. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2009;94:F407–13. doi: 10.1136/adc.2008.154567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mathew MR, Fern AI, Hill R. Retinopathy of prematurity: Are we screening too many babies? Eye (Lond) 2002;16:538–42. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6700031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Austeng D, Källen KB, Ewald UW, Jakobsson PG, Holmström GE. Incidence of retinopathy of prematurity in infants born before 27 weeks’ gestation in Sweden. Arch Ophthalmol. 2009;127:1315–9. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2009.244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Teed RG, Saunders RA. Retinopathy of prematurity in extremely premature infants. J AAPOS. 2009;13:370–3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2009.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fortes Filho JB, Eckert GU, Procianoy L, Barros CK, Procianoy RS. Incidence and risk factors for retinopathy of prematurity in very low and in extremely low birth weight infants in a unit-based approach in southern Brazil. Eye (Lond) 2009;23:25–30. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6702924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shah VA, Yeo CL, Ling YL, Ho LY. Incidence, risk factors of retinopathy of prematurity among very low birth weight infants in Singapore. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2005;34:169–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shrestha JB, Bajimaya S, Sharma A, Shresthal J, Karmacharya P. Incidence of retinopathy of prematurity in a neonatal intensive care unit in Nepal. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 2010;47:297–300. doi: 10.3928/01913913-20091118-08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen Y, Li XX, Yin H, Gilbert C, Liang JH, Jiang YR, et al. Risk factors for retinopathy of prematurity in six neonatal intensive care units in Beijing, China. Br J Ophthalmol. 2008;92:326–30. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2007.131813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fortes Filho JB, Eckert GU, Procianoy L, Barros CK, Procianoy RS. Incidence and risk factors for retinopathy of prematurity in very low and in extremely low birth weight infants in a unit-based approach in southern Brazil. Eye (Lond) 2009;23:25–30. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6702924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Binkhathlan AA, Almahmoud LA, Saleh MJ, Srungeri S. Retinopathy of prematurity in Saudi Arabia: Incidence, risk factors, and the applicability of current screening criteria. Br J Ophthalmol. 2008;92:167–9. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2007.126508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]