Abstract

Aim:

To study the views of ophthalmologists on their attitude to and the resources for ophthalmic health research in Nigeria and draw appropriate policy implications.

Materials and Methods:

Structured questionnaires were distributed to 120 ophthalmologists and ophthalmic residents who were attending an annual congress in Nigeria. Data were collected on background information, importance attributed to research, motivation for conducting research, funding, ethical oversight, literature search, and statistical support. The coded responses were statistically analyzed. P < 0.05 was statistically significant.

Results:

Eighty-nine of the 120 questionnaires were returned giving a response rate of 74.2%. Research function was rated a distant last by 49.5% of the respondents after clinical service (93.2%), teaching (63.1%), and community service (62.8%). Advancement of knowledge was the strongest motivating factor for conducting research (78.2 %). Securing funding (91.8%) and finding time (78.8%) were the major constraints. The ethical review committees were considered suboptimal by the respondents. Literature searches for research were conducted on the internet (79.3%) and was independent of age (P = 0.465). Research data were stored and analyzed on commonly available statistical software.

Conclusions:

Although study respondents regarded research highly, they were severely constrained in conducting research due to lack of access to funds and finding time away from the clinical workload. We recommend periodic (re)training on conducting good research including preparation of successful applications for research grants and allotting protected research time for ophthalmologists in Nigeria.

Keywords: Health Research, Nigeria, Ophthalmic Research, Physician Scientists

INTRODUCTION

Aspproximately 500 ophthalmologists currently practice in Nigeria that has a population of 140 million.1 Most ophthalmologists are based in tertiary eye health institutions, which are over-burdened with ophthalmic conditions that could have been appropriately addressed at the primary and secondary health care facilities if appropriate eye care resources were available.2 Apart from rendering clinical care, these ophthalmologists are routinely expected to teach, render diverse community services, and conduct research. A recent study on the views of Nigerian ophthalmologists on the issues of ophthalmic research priorities and practices revealed that the very few research works that were being conducted in Nigeria were low-budget ones that rarely had significant impacts and outcomes.3 The weak national health research systems that characterize African countries including Nigeria hinder the generation of new information and knowledge for diagnosis and treatment of diseases that are endemic to the country. Additionally, the weak national research infrastructure restricts the monitoring of health system performance; the development of new technology and products for addressing priority diseases and health conditions; and innovation directed to accessing and implementing cost-effective nationwide preventive and therapeutic interventions.4 In 2004, the World Health Organization (WHO) reviewed the current state of global health research and concluded that health research must be managed more effectively if it is to help strengthen health systems and build public confidence in science.5

Given the current deplorable state of eye health in Nigeria that was revealed in the findings of a recent nationwide ophthalmic survey,6 the need for ophthalmic research is even more acute. In Nigeria, the prevalence of blindness (<20/400 in the better eye) and severe visual impairment (<20/200–20/400; presenting vision) was 4.2% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 3.8%–4.6%) and 1.5% (95% CI: 1.3%–1.7%), respectively among adults 40 years or older.6 Blindness was associated with increasing age, being female, poor literacy, and residence in the North.6 It is estimated that 4.25 million adults, 40 years or older, have moderate to severe visual impairment or blindness (<20/63 in the better eye).6 Having recognized that there is limited capacity for conducting eye research in many developing countries, the WHO noted that other fields that are developing robust national research systems such as HIV/AIDS, malaria, and tuberculosis should be utilized where appropriate, to develop and foster ophthalmic research.7

Routine appraisals of ophthalmic research elsewhere8,9 have been beneficial in gaining insights into the various challenges and prospects for the future of ophthalmic research in the region. Particularly relevant are the insights from the third-world setting in Asia where the burden of blinding eye diseases rivals that of Nigeria and appears to be stunting the development of ophthalmic research.8 Ideally clinical ophthalmic research in a resource-challenged Sub-Saharan country such as Nigeria should thrive in view of the unique opportunities. Some of the unique opportunities as identified by Sommer10 such as the unique clinical conditions encountered due to poor populations, and the significantly higher rates of certain disease (trachoma, onchocerciasis, xerophthalmia, loa-loa, agricultural injuries). Other advantages are that the larger sample size allows for more definitive diagnostic criteria; areas where a disease is common allow for much faster evaluation of drug therapy or surgical treatment, and resource poor populations provide the only relevant setting for studying and testing simplified interventions appropriate to low-resource settings.10 In this study, we surveyed the views of medical ophthalmologists in Nigeria regarding their attitude towards ophthalmic research and the status of resources for conducting ophthalmic research. From this data we drew policy implications for ophthalmic research in Nigeria.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

As part of a larger study on various facets of research undertaken by ophthalmologists in Nigeria, this aspect of the study aimed to study the attitudes of ophthalmologists on ophthalmic research and on the status of resources for conducting health research. The data were used to recommend appropriate policy implications for ophthalmic research in Nigeria. A structured questionnaire was the primary source of data for this study. The questionnaire was distributed and collected during the 34th Annual Congress and Scientific Conference of the Ophthalmological Society of Nigeria, which was held in Lagos, Nigeria, from September 14th-17th, 2009. Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Aminu Kano Teaching Hospital, Kano, Nigeria.

Copies of the study questionnaire were distributed to 120 ophthalmologists and ophthalmic residents that attended the conference. The self-administered, anonymous questionnaire was distributed after full confidentiality of the data collected was ensured to all the study participants and the assurance that the results of this study would not be presented either at an individual study participant or hospital level. A pre-test was conducted prior to the study to assess comprehension and feasibility of the questionnaire. In the pre-test, questionnaires were administered in January 2010 on ten practicing ophthalmologists in Ilorin City, Nigeria. Findings from the pre-test indicated the need to broaden the latitude of the response options to 4 (0-3) rather than limit it to fewer options such as categorical yes or no responses.

In all, 13 questions were included in the study questionnaire. The first four were queried the background information of the respondent; others were on the relative importance of research, motivation for conducting research, sources of funding, ethical oversight, literature search, and utilization of statistician and statistical software. Generally the responses were on a graded scale of 0–3, with 0 representing none/never/lowest/least and 3 representing most/highest/greatest/always/strongest depending on the specific context of the question posed. All analyses and statistical tests were conducted using SPSS version 15.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Il, USA). Simple descriptive statistics were used to generate frequencies, percentages, and proportions. Where necessary, the Chi-square test was used to determine any significant difference with a P < 0.05 considered as statistically significant.

RESULTS

Eighty-nine out of the 120 questionnaires distributed were completed and returned (response rate, 74.2%). The age range of the respondents was 24 years to 63 years with a mean of 41.65±7.24 years. Forty-three of the 87 respondents were males and 44 were females (M:F = 1:1). Of the 86 who stated their status, 51 were Fellows/Consultants with full fellowship qualification of national or international medical postgraduate training colleges, 12 senior ophthalmic residents, 18 junior ophthalmic residents, and 5 were Diplomates i.e. mid-level ophthalmologists with Diploma certificates of national or international medical postgraduate training colleges. Of the 53 respondents who indicated their years in ophthalmic practice, 25 (47.2%) were less than 5 years, 8 (15.1%) 5–9 years, 11 (20.8%) 10–15 years, and (17.0%) over 15 years.

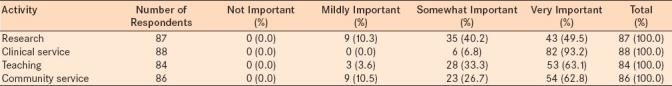

Table 1 presents the relative importance that each respondent attributed to each of the four roles that an ophthalmologist is expected to serve in a tertiary hospital in Nigeria: core hospital/clinical service, research, teaching, and community service. Though none of these roles was judged unimportant, research was rated a distant fourth (49.5%) as “very important” after clinical service (93.2%), teaching (63.1%), and community service (62.8%) [Table 1].

Table 1.

Relative importance of research graded by Nigerian ophthalmologists

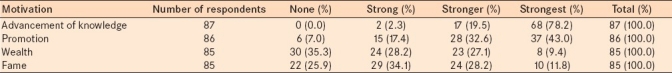

Advancement of knowledge (78.2%) and promotion (43.0%) were ranked as the two major motivating factors for conducting research among the respondents [Table 2]. Wealth (35.3%) and fame (25.9%) were not motivating factors for the majority of respondents [Table 2].

Table 2.

Motivation for conducting research by Nigerian ophthalmologists

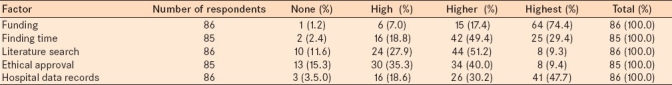

Table 3 presents the rating of the respondents to factors that impacted negatively on conducting research. Nearly all (91.8%) of the respondents rated securing funding as either the “higher” or the “highest” among factors that negatively impacted conducting research in Nigeria. This was closely followed by finding time from other schedules to conduct research (78.8%) and getting useful data from hospital records (77.9%). Table 3 illustrates the detailed rating given by the respondents on the factors [Table 3].

Table 3.

Factors that impact negatively on conducting research by Nigerian ophthalmologists

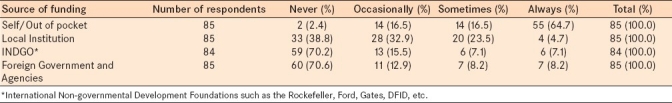

Table 4 shows the detailed frequency of utilization of various sources of funding for research by the respondents. The majority (70.2%) of the respondents had never accessed funding for research from an International Non-governmental Organization (INDGO) and 70.6% had not done so from a foreign government or agency. The majority (64.7%) had always funded their research from their personal income [Table 4].

Table 4.

Frequency of utilization of various sources of funding for research by Nigerian ophthalmologists

The Internet was “always” the source of literature search for 79.3% of the respondents while the library was "always" used by only 20.2%. The ages of the respondents appeared not to influence the overwhelming preference for the Internet for literature searches (p = 0.465)

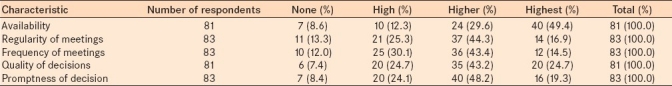

Table 5 shows the detailed characteristics of the rating of the institution ethical committees. Ethic review committees were not available to 8.6% of the respondents. Only a minority of the respondents (<20%) positively rated the various indices of functionality of their institution's ethical committees in the highest category.

Table 5.

Characterization of Institution Ethical Committees by Nigerian ophthalmologists

The respondents were also asked to rate the degree of familiarity with commonly used statistical software packages such as Excel (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA, USA), SPSS, Epi Info (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA, USA), G Power, etc. Even though about a quarter of the respondents were “very familiar” with the Excel, SPSS and Epi Info, a roughly equal proportion was “not familiar at all” with these software packages. On the question on how often the respondents had consulted a statistician in the design and/or analysis of their research projects, 12.3% had never done so, but close to half (45.7%) did so often.

DISCUSSION

The age and sex distribution of the respondents is a fair reflection of ophthalmologists in Nigeria. Our finding of near-equal representation of females relative to males among the respondents is contrary to some studies in the US,11,12 one of which11 cites low self-ability as a major barrier toward female involvement in research. The explanation may be that the cultural and social expectations and responsibilities faced by females in the Nigerian setting in contrast to males, such as household and marital responsibilities are such that they could accommodate their professional demands.

The respondents ranked their research role fourth after their clinical, community service, and teaching roles, because they were probably overwhelmed with their core ophthalmic roles. This would also explain why “finding time” was also rated in the “higher” and “highest” categories as a negatively impacting factor by 78.8% of our respondents.

Advancement of knowledge was the strongest motivating factor for 78.2% of the respondents to pursue research. This outcome is similar to findings in Australia13 among researchers who considered the “excitement of discovery” as “very” or “extremely” important by 86% of all respondents. The roles of fame and wealth as motivating factors for research were rated low in both studies.13 The challenge of adequate funding for research appears to be universal even in countries where strides have been made in funding research.13–16 Nevertheless, it is surprising that the adequacy of funding was rated either “very” or “extremely” important by 91% of all respondents in the Australian study,13 a figure that is similar to our study (91.8%).

The source of most local institutional research grants are ultimately from the Nigerian government and the local grants range from the poorly funded university senates, research institutions and hospitals to the better funded Science and Technology Education at the Post-Basic level (STEP-B), which is facilitated through a world bank loan arrangement with the Nigerian Federal Government. Local charitable bodies and Corporations are yet to play significant roles in funding major research in Nigeria.

The external research grants that are potentially available to an ophthalmic researcher from foreign governments and agencies include: Centers for Disease Control Prevention (U.S.A.), Medical Research Council (U.K.), Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft : science and humanities (DAAD, Germany), WHO, United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and UNICEF. Charitable bodies and foundations such as Gates, Ford, Carnegie, and El-Maghraby are additional potential sources of funding for ophthalmic research. All these foreign sources are very competitive and strictly merit-based to the top scorers in research grant applications; and the awards are often confined to topics of interest to the funding agencies (thematic areas) and sometimes to awardees from only some geographical locations. Research grants can only be successfully accessed through better capability to access these funds and conduct excellent research. The individual researcher however needs to take into account any bias of the different funding agencies for topics of interest, geographical areas, gender, etc.

There is a significant need to ascertain the exact reason(s) why the majority of Nigerian ophthalmologists had never accessed these popular and significant sources of external governmental and non-governmental research funds and instead funded their research from their personal savings. Their savings could only provide relatively paltry amounts needed for meaningful research and this would consequently limit the depth, scope, outcome, and impact of research. Were they either unwilling or more likely unable to write convincing applications for research grants? This is an important area for further study as governmental and non-governmental sources of funding are crucial to researchers worldwide and especially in a resource-challenged setting such as Nigeria.

Recent improvement in information technology and access to information technology has greatly improved the capability of third-world researchers to search for literature and store and analyze their data using affordable statistical software. Recently, libraries have been unable to acquire volumes of journals and books, which would explain why only a minority of our respondents would conduct their literature searches at libraries. However, recently major Nigerian biomedical libraries have acquired subscriptions to a number of electronic information resources (databases), which has continued to enhance teaching, learning, and research. Notable databases for free medical journal articles for an ophthalmic researcher include the African Journal Online (AJOL), WHO HINARI, Iowa University Library, and Biomedical Central.

Though the respondents in our study confirmed the availability of ethical review committees in their tertiary health facilities,17 most of the committee did not appear to be functioning optimally. This would probably explain why our respondents did not give high ratings to the quality of the decisions and the promptness of decisions of their local ethical boards. A recent revelation that about 25% of health-related studies in developing countries were not subjected to some form of ethics review by an international review board, national ethics board, or ministry/department of health is troublesome.16 In the current era of globalized biomedical research, good ethics stewardship demands that every country, irrespective of its level of economic development, should have in place a functional research ethics review system in order to protect the dignity, integrity, and safety of its citizens, who participate in research.18

Although the Nigerian heath reform bill is yet to be formally promulgated into law, it is comforting to note that the draft bill devotes a section to health research issues. A proposed national health research committee shall have the responsibility to: (a) determine the extent of health research to be conducted by public and private health authorities; (b) ensure that the health research agenda and research resources focus on priority health problems; (c) develop and advise the Minister on the application and implementation of an integrated national strategy for health research; and (d) coordinate the research activities of public and private health establishments. Findings from this study should be of use to the would-be members of the proposed Nigerian national health research committee, in their quest to implement the goals outlined in the research agenda of the WHO Task Force on Health Systems Research.19

CONCLUSION

A majority of ophthalmologists in our study sample did not rate their research role highly and were motivated to conduct research largely by their wish to advance knowledge. Their major constraints to conduct research were research funding and protected time from their clinical functions. They had very poor access to national and international sources of research funding and had to largely fund their research personally. Ethical review committees in their institutions needed to be more functional. Most literature searches were conducted on the Internet and researchers stored and analyzed their research data with readily available statistical software. Training in conducting good research and on how to successfully apply for research grants should be compulsory during undergraduate as well as post-graduate training. Providing some protected research time to ophthalmologists is highly recommended. Further studies with an emphasis on the quality of research training and outcomes from the training are recommended.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Federal Republic of Nigeria: 2006 population census. [Last accessed on 2008 Sep 22]. Available from: http://www.nigerianstat.gov.ng/Connections/Pop2006.pdf .

- 2.Mahmoud AO, Kuranga SA, Ayanniyi AA, Babata AL, Adido J, Uyanne IA. Appropriateness of ophthalmic cases presenting to a Nigerian tertiary health facility: Implications for service delivery in a developing country. Niger J Clin Pract. 2010;13:280–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mahmoud AO, Ayanniyi AA, Lawal A, Omolase CO, Ologunsua Y, Samaila E. Ophthalmic research priorities and practices in Nigeria: An assessment of the views of Nigerian ophthalmologists. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol. 2011;18:164–9. doi: 10.4103/0974-9233.80707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kirigia JM, Wambebe C. Status of national health research systems in ten countries of the WHO African Region. BMC Health Serv Res. 2006;6:135. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-6-135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Report on Knowledge for Better Health - Strengthening Health Systems. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2004. World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kyari F, Gudlavalleti MV, Sivsubramaniam S, Clare E, Gilbert CE, Abdull MM, et al. Prevalence of blindness and visual impairment in Nigeria: The national blindness and visual impairment survey. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50:2033–9. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-3133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Opportunities in Global Eye Research: Report of a WHO Consultation. Geneva: WHO; 2003. Sep 8-10, World Health Organization Prevention of Deafness and Blindness; p. 1. WHO/PBL/04.94. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wong TY, Tan DT. The SERI-ARVO meeting and future challenges of ophthalmic research in Asia. Br J Ophthmol. 2003;87:379–80. doi: 10.1136/bjo.87.4.379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stefansson E, Zetterstrom C, Ehlers N, Kiilgaard JF, la Cour M, Sigurdsson H, et al. Nordic research in ophthalmology. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2003:556–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1395-3907.2003.00177.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sommer A. Clinical research: A primer for ophthalmologists. Prepared for the International Council of Ophthalmology. [Last accessed on 2010 Jul 20]. Available from: http://www.icoph.org/pdf/PrimerClinicalResearch.pdf .

- 11.Bakken LL, Sheridan J, Carnes M. Gender differences among physician-scientists in self-assessed abilities to perform clinical research. Acad Med. 2003;78:1281–6. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200312000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lloyd T, Phillips BR, Aber RC. Factors that influence doctors’ participation in clinical research. Med Educ. 2004;38:848–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2004.01895.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shewan LG, Glatz JA, Bennett CC, Coats AJ. Contemporary (post-Wills) survey of the views of Australian medical researchers: Importance of funding, infrastructure and motivators for a research career. Med J Aust. 2005;183:604–5. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2005.tb00051.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kavallaris M, Meachem SJ, Hulett MD, West CM, Pitt RE, Chesters JJ, et al. Perceptions in health and medical research careers: The Australian Society for Medical Research Workforce Survey. Med J Aust. 2008;188:520–4. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2008.tb01766.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zinner DE, Campbell EG. Life-science research within US academic medical centres. JAMA. 2009;302:969–76. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Campbell EG. The future of research funding in academic medicine. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1482–3. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0900132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hyder AA, Wali SA, Khan AN, Teoh NB, Kass NE, Dawson L. Ethical review of health research: A perspective from developing country researchers. J Med Ethics. 2004;30:68–72. doi: 10.1136/jme.2002.001933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kirigia JM, Wambebe C, Baba-Moussa A. Status of national research bioethics committees in the WHO African region. BMC Med Ethics. 2005;6:10. doi: 10.1186/1472-6939-6-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Task force on health systems research. Informed choices for attaining the millennium development goals: Towards a cooperative agenda for health systems research. Lancet. 2004;364:997–1003. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17026-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]