Abstract

Epiphora is a common complaint of patients who present to an Ophthalmology Clinic. In many cases, epiphora is due to an obstruction in the lacrimal drainage system. However, a subgroup of symptomatic patients with epiphora has a patent lacrimal drainage system. Such cases are usually termed ‘functional obstruction’ and / or ‘stenosis of the lacrimal drainage system’. Various etiologies and diagnostic and therapeutic approaches have been described in literature, which implies the lack of a standardized approach. This article will review the evolving diagnostic and therapeutic approaches in literature, and in the end, propose a paradigm in approaching this group of patients.

Keywords: Canalicular stenosis, Epiphora, Functional lacrimal obstruction, Nasolacrimal duct, Stenosis, Punctal stenosis

INTRODUCTION

Anatomy

The lacrimal drainage apparatus is divided into the proximal and distal sections. The proximal section includes the punctum, canaliculus, and the common canaliculus, successively.1–3 The distal lacrimal drainage system consists of the lacrimal sac and the nasolacrimal duct that finally open into the lateral nasal wall, below the inferior meatus.1 The lacrimal drainage system begins at the superior and inferior puncta. The external lacrimal punctum is approximately 0.3 mm in diameter.4 The papilla is the elevated tissue surrounded internally by a ring of connective tissue.4 The lacrimal puncta are components of tarsal plates in both the upper and lower lids.5 The upper punctum is 6.0 mm from the medial canthus and the lower 6.5 mm.2 Both the superior and inferior puncta should sit in apposition to the globe in the tear lake.4 The puncta allow entrance into the ampulla, which is directed perpendicularly to the lid margin for 2 mm and after a 90-degree bend continues as the canaliculi.1 The upper and lower canaliculi course along the lid margins and measure 8 – 10 mm in length and 0.5 – 1.0 mm in diameter.3 In approximately 90% of the individuals, the distal section of the canaliculi joins to form the common canaliculus before entering the lacrimal sac.3 At the entrance of the lacrimal sac, the common canaliculus may dilate slightly, forming the sinus of Maier.3 The canaliculi are lined with stratified, squamous, non-keratinized, non-mucin-producing epithelium surrounded by elastic tissue, which permits dilation up to two-to-three times the normal diameter.3 The valve of Rosenmuller is a functional one-way valve that is presumably formed by the mucosal folds and the manner in which it enters the sac.1–3 The common canaliculus bends behind the medial canthal tendon before entering the lacrimal sac at an acute angle. The oblique entrance prevents a tear reflux from the sac back into the canaliculi.1,2 The lacrimal sac lies in the lacrimal sac fossa, behind the medial canthal tendon.1,2 The lacrimal fossa is bordered by the anterior and posterior lacrimal crests, to which the medial canthal tendon attaches.2 Its medial aspect is tightly adherent to the periosteal lining of the fossa. The medial canthal tendon is a complex structure, composed of anterior and posterior crura.1,2 The superficial head attaches to the anterior lacrimal crest, and the deep head (Horner's muscle), to the posterior lacrimal crest.1,2 The medial wall of the fossa (lamina papyracea) is composed of the lacrimal bone posteriorly and the frontal process of the maxillary bone anteriorly.1 The total sac measures a length of 12–15 mm vertically and 4–8 mm anteroposteriorly.1 The fundus of the sac extends above the tendon for 3 to 5 mm. The sac rests in the lacrimal sac fossa, with its medial aspect tightly adherent to the periosteal lining of the fossa. The nasolacrimal duct travels inferolaterally and slightly posteriorly, in its bony course, to the inferior turbinate for an intraosseous course of 12–13 mm and extends another 2–3 mm into the inferior meatus.1 The opening of the nasolacrimal duct is located 25–30 mm posterior to the lateral margin of the anterior nares.1 The lacrimal pump actively drains the tears into the puncta, propelling them forward.2 The pump action is due to blinking, which results in a contraction of the deep heads of pretarsal and preseptal orbicularis.1 A classic disorder of this functional component is seen in facial nerve palsy — the power of the blink reflex (orbicularis muscle) is decreased, and tearing occurs without obvious anatomical obstruction.

PUNCTAL STENOSIS

Punctal stenosis is a common cause of epiphora.6,7 It might be congenital or arise from acquired causes.8 Punctal stenosis can be an isolated disorder or associated with canalicular stenosis, eyelid laxity or malposition.8–12 An associated nasolacrimal duct obstruction can be found in 8.5% of the cases.6 Kashkouli et al.6 suggest that associated upper tear drainage stenosis (canaliculi and common canalicular) is present in almost 50% of the patients with acquired external punctal stenosis (AEPS). Association of AEPS with canalicular and common canalicular stenosis has been reported with trachoma,13 systemic chemotherapy,8,10,11,14 cicatrizing diseases of the conjunctiva,15,16 and medial ectropion.17 Fezza et al.,18 have evaluated the sequelae of systemic 5-FU and have found varying degrees of punctal and canalicular stenosis, severe enough to warrant surgical intervention. McNab19 has reported about 14 patients on topical ocular medications (six on topical anti-glaucoma therapy) from three weeks to 20 years, who developed lacrimal punctal and canalicular stenosis.

Etiology

The common causes of acquired punctual stenosis include infectious and inflammatory eyelid disorders, ocular surface diseases, systemic and topical medications, such as, antiviral, anti-glaucoma and anti-neoplastic medications, eyelid tumors, and trauma.6,8–10,13,14,19–22 Chronic punctal eversion may also result in stenosis.17 Paclitaxel used for the treatment of head and neck angiosarcoma can cause severe punctual and canalicular stenosis.23 Kashkouli et al.6 reported punctal stenosis after one year of topical latanoprost therapy. They6 reported chronic blepharitis (infectious ulcerative, seborrheic, or rosacea) as a cause of external punctual stenosis in 45% of their patients, unknown etiology in 27%, and medial ectropion in 23%.6 Edelstein and Reiss24 found that cicatricial changes from chronic blepharitis caused recurrent punctal stenosis after wedge punctoplasty. Stenosis of the punctum and proximal canaliculus are reported to be frequent after spontaneous loss of punctal plugs, by accumulation of debris, including inflammatory reactions resulting in scar formation or the act of probing itself, prior to plug insertion.25–32 Boldin et al.,33 hypothesized that mechanical stress on the mucosa might lead to mild chronic inflammation, causing stenosis of the punctum. The histological findings associated with topical anti-glaucoma medications include conjunctival metaplasia, decrease in goblet cells and increased number of sub-conjunctival fibroblasts, macrophages, and other inflammatory cells, which may account for punctal-canalicular stenosis in this group of patients.16,34–41 Tissue atrophy and involutional changes cause the dense fibrotic structures of the punctum to be less resilient and the surrounding orbicularis fibers to become atonic, resulting in punctal stenosis.15

Diagnosis

A detailed history of any systemic or topical medication, surgery, trauma or scarring, and infection is warranted. It is valuable to grade the severity of epiphora using a uniform grading system such as the Munk scale [Table 1].42 Slit lamp examination starts with recognizing the papilla, presence of a membrane or fibrosis over the punctum, punctum size, tear meniscus height, eyelid margin, conjunctiva around the punctum, eyelid malposition, position of the punctum in the tear lake, and any sign of previous surgery. The Schirmer test,43 tear break up time,44 ocular surface staining, and tear meniscus height will highlight any associated ocular surface abnormalities. Abnormal dye disappearance test shows an abnormal tear drainage system and is especially helpful in pediatric patients.44 Examination of eyelid laxity [Figure 1] by means of the eyelid distraction test45 will assist in determining the health of the lacrimal pump

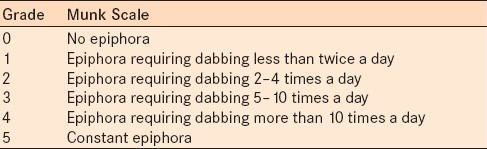

Table 1.

Munk scale for epiphora grading42

Figure 1.

Digital subtraction test of lower eyelid laxity

Recognizing the relative degrees of punctal stenosis is a fundamental parameter for assessment of the severity of the underlying fibrosis and inflammation, and directs the practitioner to the best treatment option. Hence, recording the punctal size will make management easier. The benefits of grading are to standardize the terms describing the external lacrimal punctum, which would make comparison of the outcomes of various studies easier.46 A lacrimal punctal grading system (grades 0 – 5) has been introduced by Kashkouli et al.,6 in 2003 [Figure 2]. The reliability and good inter-observer correlation of this grading system were confirmed in 2008.46 Kashkouli et al.'s6 grading system is based on punctual shape and size on slit lamp examination as well as the ease of introducing a punctal dilator [Table 2]. Although very good agreement was found between the observers, less experienced observers tended to overestimate the punctal grading.46 Any other lacrimal drainage stenosis could be defined by performing diagnostic irrigation and probing. Following punctal dilation, a #00 Bowman probe was passed through the punctum and ampulla into the canaliculus. A hard stop signifies a patent canaliculus. Usually a gritty sensation or mild resistance while passing the probe implies canalicular stenosis. Soft resistance to the probe that cannot be overcome may signify obstruction. Location of the canalicular stenosis and obstruction can be measured by grasping the punctal end of the probe and withdrawing it from the canaliculus [Figure 3]. Irrigation of the lacrimal system can provide valuable information about the anatomic patency of the lacrimal drainage system, especially the inferior section [Figure 3]. Irrigation is performed with a 2-ml syringe filled with normal saline and a 26-G lacrimal cannula. Return from the same punctum with some passage of fluid to the nose could imply canalicular stenosis. Common canalicular stenosis typically results in the return of clear fluid from the opposite punctum, with some nasal passage. Complete nasolacrimal duct (NLD) obstruction results in the regurgitation of saline and some mucous through the other punctum. Patients with stenotic NLD show passage of fluid to the nose and minimum reflux from the other canaliculus.

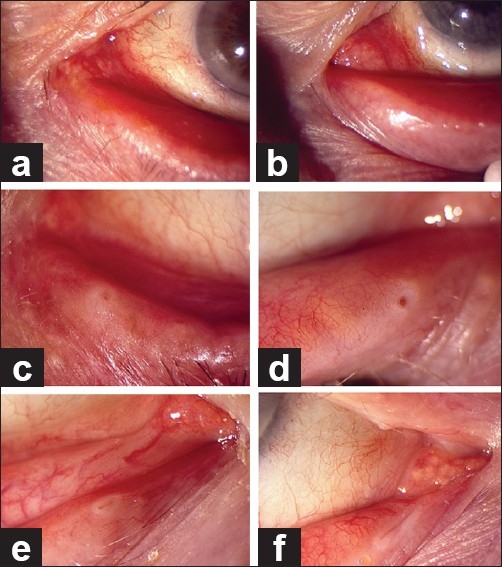

Figure 2.

External lacrimal punctal grading: Grade 0 (a), 1 (b), 2 (c), 3 (d), 4 (e), and 5 (f)

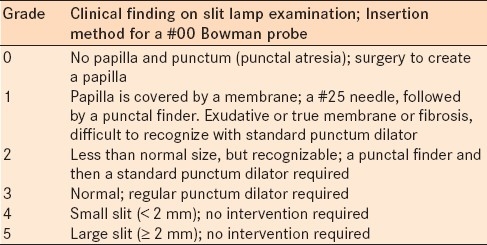

Table 2.

Grading of External Lacrimal Puncum46

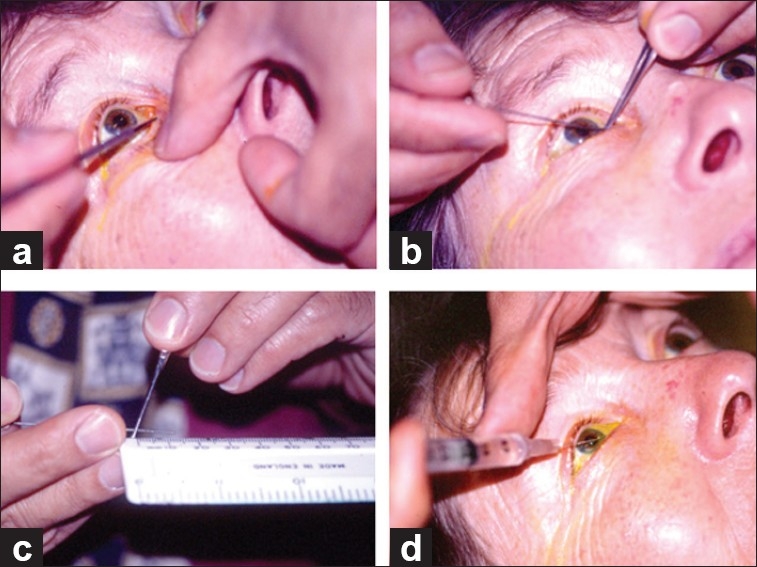

Figure 3.

Diagnostic probing and irrigation of the lacrimal drainage system: punctal dilation (a), advancement of probe (b), measuring the soft stop in the canaliculus, up to the tip of the probe (c), and nasolacrimal irrigation (d)

TREATMENT

The basic principles in the treatment of punctal stenosis include creating an adequate opening, while maintaining the position of the punctum against the lacrimal lake, and preserving the lacrimal pump function.47,48 The reported success rate ranges between 76 and 96% for the treatment of acquired external punctal stenosis, with better results in cases of the lower eyelid position and normal diagnostic probing and irrigation test.8,24,48–54

Repeated dilation of the stenotic punctum is a simple procedure that may provide temporary improvement of the symptoms, but recurrences of stenosis are common unless additional procedures are performed.48

Different methods of punctoplasty have been used to augment punctal size, including 1, 2, and 3-snip punctoplasty,55–58 punctum pucker procedure,51 posterior punctectomy with intraoperative mitomycin-C (MMC),47 one-snip punctoplasty, with mini Monoka tube insertion,52 microsurgical punctoplasty,53 punch (wedge) punctoplasty,24 laser punctoplasty, and electrocautery.49 Two-snip57 and three-snip58 punctoplasties have been advocated after failure of one-snip punctoplasty. Bodian59 introduced unroofing the proximal canaliculus and noted recurrent scarring in two of the seven eyes. Offut and Cowen53 reported a microsurgical technique in which they externalized the vertical canaliculus using an operating microscope for meticulous dissection of tissues around the punctum.

Mathew et al.7 described a simple technique of inserting the mini Monoka using a Nettleship dilator without a snip procedure. Kashkouli et al.,52 suggested a horizontal one-snip procedure to facilitate punctal canalicular insertion. Kashkouli et al.52 performed punctoplasty and monocanalicular stenting in order to address the associated canalicular and common canalicular stenosis and concluded that while less stenotic puncta (grade 2) responded well to simpler procedures such as a snip procedure or punctal dilation, more stenotic puncta (grade 1 or 0) were needed to maintain patency.52 Complete functional success in 77.4% and anatomical success in 96.2%, after a mean follow-up of 18.5 months, was reported.52 In patients with AEPS and NLD stenosis, punctoplasty with bicanalicular stent insertion was performed.

Fein49 reported early success in 28 of 35 eyes after cautery to treat AEPS, with recurrence of epiphora in nine cases of 24 eyes after a one-year follow-up. Kristan and Branch15 inserted a temporary punctal plug after a one-snip punctoplasty and achieved symptomatic improvement in all 25 AEPS. Microsurgical punctoplasty had 96% functional and 100% anatomic success rates in 28 AEPS cases.53 Posterior punctectomy with the use of MMC was performed by Ma’luf et al.,47 with a functional success rate of 96% and an anatomical success rate of 100% at a one-year follow-up. MMC was also used with one-snip punctoplasty to open the stenotic punctum after two unsuccessful attempts.54 Chak60 reported a conservative method of rectangular three-snip punctoplasty (two vertical cuts on either side of the vertical canaliculus and one cut at the base).

CANALICULAR STENOSIS

The frequency of canalicular obstruction has been reported to be between 16 and 25% in patients with epiphora.61 The most common symptom is intermittent or constant tearing. Canalicular obstructions could be anatomically classified as: proximal with involvement of the proximal 2–3 mm, mid-canalicular obstructions 3–8 mm from the punctum, and distal obstructions as defined by a membrane at the opening of the common canaliculus to the lacrimal sac.62

Etiology

A plethora of factors have been reported to be associated with canalicular obstructions [Table 3]. In congenital anophthalmos or severe microphthalmos the lacrimal system is affected in up to 78% of the cases, mostly due to canalicular stenosis (58%), and less commonly, common canalicular stenosis (7.3%).62,63

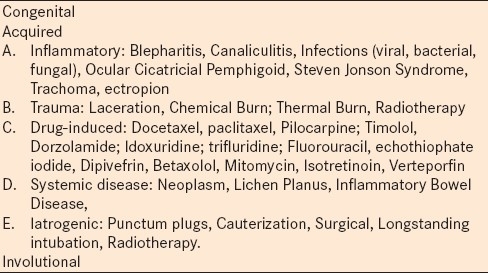

Table 3.

Etiologies of Punctal-Canalicular Obstruction

Topical anti-glaucoma medications have repeatedly been associated with lacrimal drainage stenosis.19,37–40,64,65 Kashkouli et al.,64,65 reported a significantly higher frequency of both upper (76.92%) and lower (50%) lacrimal drainage system obstruction in patients receiving topical anti-glaucoma medications, including pilocarpine, timolol, and dorzolamide, as a single or combination therapy. Additionally, the risk of lacrimal drainage obstruction was increased by the use of combination therapy and the risk of obstruction was almost twice that of the general population and significantly higher in the upper lacrimal drainage system.64,65 Docetaxel has been reported to cause epiphora due to canalicular stenosis.66 The mechanisms of drug-induced lacrimal drainage obstruction may be related to the medications themselves, preservatives or duration of topical treatment.64 This condition has been proposed to be either dose-related or idiosyncratic.19 There are some reports of upper lacrimal drainage system obstruction associated with topical MMC, used in glaucoma filtering surgery and ocular surface neoplasia.12 However, Kashkouli et al.,67 conducted a comparative study and concluded that there was no significant effect of topical MMC, used during filtration surgery, on lacrimal system obstruction. Canalicular obstruction could also occur after photodynamic therapy with verteporfin, used for treating choroidal neovascular membranes.68

Diagnosis

History of any concurrent ocular or systemic disease, topical and systemic medications, surgeries, allergy, trauma, previous ocular interventions, including those for dry eye disease, need to be recorded. A comprehensive ophthalmic examination should be performed, including staining of the ocular surface, to detect any tear film abnormality, examination of lid, especially the medial aspect, for malpositions (entropion, ectropion), punctual grading, and assessment of conjunctival and caruncular apposition to the punctum. The medial canthal region should be palpated and compressed, looking for any regurgitation through the puncta (regurgitation test). Mucopurulent regurgitation signifies NLD obstruction.

Dye disappearance test (DDT) is useful to differentiate hyperlacrimation from lacrimal drainage obstruction (whether functional or anatomical). In this test, one drop of fluorescein 2% or a fluorescein strip wetted by artificial tears is gently placed or briefly inserted in the inferior fornix of each eye. The tear meniscus height is evaluated with cobalt blue light after five minutes for the clearance of fluorescein and symmetry of dye in both eyes. Anatomic patency of the lacrimal drainage system can further be assessed by lacrimal irrigation and in-office probing [Figure 3].

Dacryocystography is of little diagnostic value in canalicular disorders, especially canalicular stenosis.69 Lacrimal scintigraphy could be useful in those patients with presumed functional epiphora.70 Canalicular endoscopy can directly reveal the site and nature of the obstructing lesion.71 However, the price and availability hinder its use on a routine basis in most clinics.

Treatment

Goals of treatment for canalicular stenosis include: relieving the patients’ symptoms; maintenance of anatomic patency of the canaliculi; preventing progression to complete obstruction, and maintaining the function of the opposite canaliculus. Timely diagnosis and appropriate management of a canalicular stricture can prevent more complicated surgeries such as conjunctivodacryocystorhinostomy (CJDCR). The underlying causes of canalicular obstruction must be determined and addressed [Table 3]. The site and extent of stenosis must be determined.

One-snip punctoplasty and canalicular intubation (mini Monoka) is a simple and effective method of treating punctal canalicular stenosis.52 Balloon canaliculoplasty is an alternative treatment option in patients with canalicular stenosis. Following graded dilation of canaliculus with Bowman's probes, a 2-mm balloon dilator is introduced into the canaliculus and advanced approximately 10 mm to the lacrimal sac, until a hard stop is felt. The balloon is then inflated to a pressure of four bars for 90 seconds and then deflated. Subsequently it is inflated to four bars for 60 seconds and then deflated. The procedure is concluded with a silicone intubation.71 Zoumalan et al.,72 performed this method on 41 canaliculi and achieved 76.2% partial or complete success.

Caversaccio et al.,73 studied the results of double bicanalicular silicone tubes placed after endoscopic DCR in 44 patients with canalicular stenosis. They73 found that 32 (63%) of the patients became symptom-free.73 Hwang et al.,74 compared double versus single intubation of canaliculi during dacryocystorhinostomy (DCR) for canalicular stenosis and found higher anatomical success rates (96.5%) in the double intubation group and the same functional success rate in both groups. A fine membranous obstruction of the common canaliculus can be easily visualized by passing a lacrimal probe and can be removed during DCR.75

Endocanalicular approaches for severe stenosis and complete obstruction of canaliculi have recently gained popularity.71 Endocanalicular lacrimal probes are fine metal tubes within which instruments such as laser, drill or trephine may be used to investigate or treat the lacrimal drainage system.76 Non-endoscopic canalicular trephination for obstruction yielded variable results, depending on the affected segment. Eyes with distal bicanalicular, common canalicular, and proximal bicanalicular obstruction achieved 66, 59, and 55% success, respectively.76 Nemet et al.,77 found this approach effective in four of five (80%) cases with common canalicular and distal canalicular obstructions. Both microtrephination and balloon canaliculoplasty have also been used in canalicular strictures.78 Laser canaliculoplasty71,79 has also been used in focal stenosis (approximately 2 mm or less) within the canaliculi. The success rate varies between 43 and 84%.62,71,79

PARTIAL AND FUNCTIONAL NASOLACRIMAL DUCT OBSTRUCTION

Functional NLD obstruction, by definition, is epiphora without detectable lacrimal drainage system obstruction. The term ‘functional obstruction’ is confusing, as it implies anatomically patent lacrimal passages with a physiological dysfunction.80 Different reasons have been cited in the literature, including partial obstruction of NLD, which is patent upon positive-pressure irrigation through the canaliculus,81–83 lacrimal pump failure due to eyelid laxity,84 conjunctivochalasis85 and megalo-caruncle [Figure 4]86 occluding the punta, punctal apposition [Figure 5],87 and subtle medial ectropion [Figure 6]preventing punctual apposition to the lacrimal lake.17 Tearing without mucopurulent discharge is the most common presenting symptom.

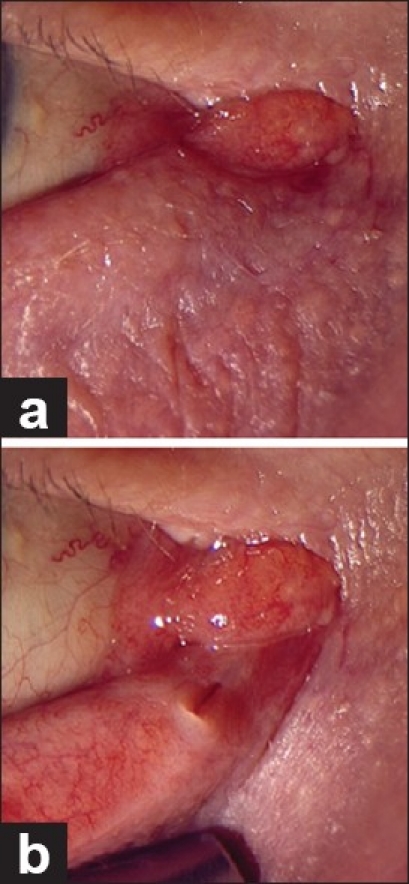

Figure 4.

Megalo-caruncle obstructing the punctum before (a) and after (b) lower eyelid pull

Figure 5.

Punctal apposition in primary gaze (a) and up-gaze (b)

Figure 6.

Subtle punctal ectropion

The caruncle may increase in size in older patients, probably as a result of senile hypertrophic changes, and in Graves’ ophthalmopathy.86 This enlarged caruncle may prevent nasal sliding of the lower punctum during eyelid closure and push the medial lower eyelid off the globe. Similarly, conjunctivochalasis may cause epiphora due to blockage of the punctum by redundant bulbar conjunctiva protruding over the lower eyelid margin and blocking the entrance to the punctum.85

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of functional lacrimal system obstruction is based on a history of epiphora, positive dye disappearance test, and free passage of fluid on irrigation test. The diagnosis of partial NLD obstruction is the same, except for some cases that might have both passage of fluid into the nose as well as minimum reflux from the other canaliculus.88,89 Some90 define the functional obstruction as (a) a negative Jones I and positive Jones II dye test, or (b) a freely patent nasolacrimal system to irrigation with minimum or no reflux from the upper canaliculus or punctum. At times, a technetium scan or dacryocystography assist in establishing the diagnosis and classification of NLD stenosis.70,90,91 Based on lacrimal scintigraphy, a pre-sac delay is diagnosed if the tracer fails to reach the sac by the end of the dynamic phase. A post-sac delay is diagnosed if there is early filling of the sac, but it continues to remain full of contrast at the end of the study.90 Appropriate examination of the eyelid and conjunctiva reveals laxity of the eyelid, facial nerve palsy, conjunctivochalasis, megalo-caruncle, and punctal apposition, if they are taken into consideration at the time of examination. Rosenstock et al.,80 have shown that physiological dysfunctions are almost always located in the upper system. Others90 believe that partial NLD obstruction, whether pre-sac or post-sac, are also in this category. In fact, most of the time there are multiples causes of functional obstruction of the lacrimal drainage system. Hence, all entities other than complete obstruction of the lacrimal system might be included in the category of functional obstruction. Recognizing each etiology and treating it appropriately may obviate more invasive procedures.

Treatment

Management of partial NLD obstruction includes dacryocystorhinostomy, balloon catheter dilatation, with and without silicone intubation, silicone intubation (monocanalicular, bicanalicular, double bicanalicular), and probing.70,90–107

External DCR is a widely used standard procedure with success rates ranging from 70 to 95%, but may be complicated by nasal bleeding, infection, cerebrospinal fluid leak, punctal eversion, and a skin scar.90,93,94 Delaney90 reviewed the success rate of external DCR for adult patients with partial LD obstruction and found subjective success rates of 84% at four months of follow-up and 70% at three years of follow-up. Endonasal DCR success rates vary from 63 to 94% and may be complicated by nasal bleeding, nasal mucosal scarring, granuloma, osteotomy-nasal septal adhesion, and damage to the orbital contents.96,97 Wormald and Tsirbas70 assessed the results of endonasal DCR in adult patients with partial LD obstruction at a minimum of 12 months’ follow-up, and reported an 84% success rate . In another study, standard endonasal DCR was compared with laser endonasal DCR in adult patients with partial LD obstruction, with a success rate of 82% in the former and 71.5% in the latter.98 Better success of DCR for post-sac stenosis (80%) rather than pre-sac stenosis (46%), with three years of follow-up has been reported.90

Balloon catheter dilatation with and without intubation has been used for NLD stenosis and yielded success rates between 53 and 68%.82,91,99,100 Perry et al.,101 reported an objective success rate of 73% at six months and a subjective success rate of 60% at six months in adult patients. Couch and White82 reported lower success rates, with complete resolution of tearing in 56% of the patients and reduced tearing in 34%, after a mean follow-up of seven months. However, Kashkouli and associates102 compared endoscopically assisted balloon dacryocystoplasty and silicone intubation with silicone intubation alone in adults, and found no difference in the outcome between the two treatment methods (61 vs. 54%).

Bicanalicular or monocanalicular silicone intubation have been used with success rates of 53 to 60%.92,95,103,104 Kashkouli and associates89 compared monocanalicular versus bicanalicular intubation for NLD stenosis in adults and found no difference in the success rates (61.5 vs. 59%, respectively). Double bicanalicular silicone intubation was used in 18 patients with NLD stenosis and resulted in complete resolution of symptoms in 79% of the patients.81 Fayet et al.,105 found that the success rate did not seem to correlate with the duration of intubation after one month, but the complication rate did. Frueh106 mentioned that most complications from silicone tubing occurred in the interval of two to four months after placement of the tubing. In general, a shorter time of intubation is now being considered.89,102

Probing was shown to have limited success in approximately 50% of the adult patients with NLD stenosis.107

One important point in comparing different results is the duration of the follow-up. In general, longer follow-up is associated with lower success rates regardless of the type of treatment.

Eyelid and conjunctival causes of functional lacrimal drainage obstruction should also be addressed appropriately. One of the major causes in this category is the eyelid laxity in which lacrimal pump failure occurs and results in a matted eye.45 Lateral canthal tightening is the mainstay of treatment in this regard.84,108,109 Liu and Stasior108 suggested a cause and effect relation between longer flaccid eyelids and tearing.

Caruncle and bulbar conjunctiva can mechanically occlude the entrance to the lacrimal drainage system. Some patients with Epiphora, classified as functional lacrimal drainage obstruction at presentation, have presented with enlarged caruncles.86 Carunculectomy has been reported to alleviate epiphora in 77% of these patients.86 Bulbar conjunctivochalasis occluding the lower punctum must be treated.85

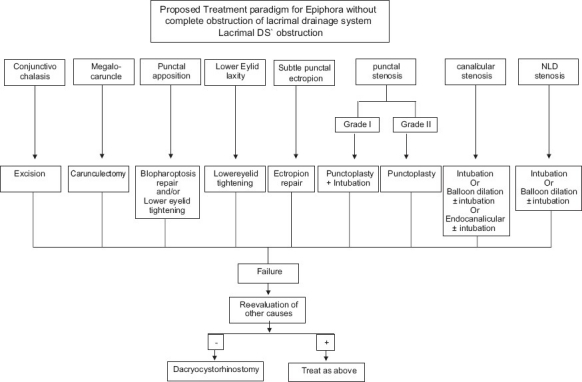

In conclusion, there are different etiologies to be evaluated and addressed in patients with epiphora without complete obstruction of the lacrimal drainage system, a condition referred to as functional obstruction. We propose a paradigm for treatment of such patients, taking into consideration that in some cases there may be more than one cause of epiphora requiring simultaneous treatment [Figure 7].

Figure 7.

Proposed paradigm for treatment of epiphora without complete obstruction of the lacrimal drainage system

Footnotes

Source of Support: Tehran University Eye Research Center, Tehran, Iran

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Basic and Clinical course. Section 7, Orbit, Eyelids and Lacrimal System. American Academy of Opthalmology. 2008-2009:259–64. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Basic and Clinical course. Section 2, Fundamentals and Principles of Ophthalmology. American Academy of Opthalmology. 2008-2009:36. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tucker NA, Tucker SM, Linberg JV. The anatomy of the common canaliculus. Arch Ophthalmol. 1996;114:1231–4. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1996.01100140431010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hirschbein MJ, Stasior GO. In: Oculoplastic surgery, the Essentials. 1st ed. New York: Theime; 2001. Lacrimal System; pp. 263–4. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Takahashi Y, Kakizak H, Nakano T, Asamoto K, Ichinose A, Iwaki M. Anatomy of the vertical lacrimal canaliculus and lacrimal punctum: A macroscopic study. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;27:384–6. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0b013e318219a54b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kashkouli MB, Beigi B, Murthy R, Astbury N. Acquired external punctal stenosis: Etiology and associated findings. Am J Ophthalmol. 2003;136:1079–84. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(03)00664-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mathew RG, Olver JM. Mini-Monoka made easy: A simple technique for Mini-Monika insertion in acquired punctal stenosis. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;27:293–4. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0b013e31820ccfaf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hurwitz JJ. The Lacrimal System. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott-Raven; 1996. pp. 149–53. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weston BC, Loveless JW. Canalicular stenosis due to topical use of fortified antibiotics. Can J Ophthalmol. 2000;35:334–5. doi: 10.1016/s0008-4182(00)80062-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Esmaeli B, Valero V, Ahmadi MA, Booser D. Canalicular stenosis secondary to docetaxel (taxotere): A newly recognized side effect. Ophthalmology. 2001;108:994–5. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(00)00640-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee V, Bentley CR, Olver JM. Sclerosing canaliculitis after 5-fluorouracil breast cancer chemotherapy. Eye (Lond) 1998;12:343–9. doi: 10.1038/eye.1998.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Billing K, Karagiannis A, Selva D. Punctal-canalicular stenosis associated with mitomycin-C for corneal epithelial dysplasia. Am J Ophthalmol. 2003;136:746–7. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(03)00393-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tabbara KF, Bobb AA. Lacrimal system complications in trachoma. Ophthalmology. 1980;87:298–301. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(80)35234-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Seiff SR, Shorr N, Adams T. Surgical treatment of punctal-canalicular fibrosis from 5-fluorouracil therapy. Cancer. 1985;56:2148–9. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19851015)56:8<2148::aid-cncr2820560845>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kristan RW, Branch L. Treatment of lacrimal punctal stenosis with a one snip canaliculotomy and temporary punctal plugs. Arch Ophthalmol. 1988;106:878–9. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1988.01060140020006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schwab IR, Linberg JV, Gioia VM, Benson WH, Chao GM. Foreshortening of the inferior conjunctival fornix associated with chronic glaucoma medications. Ophthalmology. 1992;99:197–202. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(92)32001-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O’Donnell FE., Jr Medial ectropion: Association with lower lacrimal obstruction and combined management. Ophthalmic Surg. 1986;17:573–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fezza JP, Wesley RE, Klippenstein KA. The treatment of punctal and canalicular stenosis in patients on systemic 5-FU. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers. 1999;30:105–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McNab AA. Lacrimal canalicular obstruction associated with topical ocular medication. Aust N Z J Ophthalmol. 1998;26:219–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.1998.tb01315.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jager GV, Van Bijsterveld OP. Canalicular stenosis in the course of primary herpes simplex infection. Br J Ophthalmol. 1997;81:332. doi: 10.1136/bjo.81.4.329d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brink HM, Beex LV. Punctal and canalicular stenosis associated with systemic fluorouracil therapy. Report of five cases and review of the literature. Doc Ophthalmol. 1995;90:1–6. doi: 10.1007/BF01203288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cherry PM, Falcon MG. Letter: Punctal stenosis caused by idoxuridine or acrodermatitis entropathica. Arch Ophthalmol. 1976;94:1632. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1976.03910040462032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mc Cartney E, Valluri S, Rushing D, Burgett R. Upper and lower nasolacrimal duct stenosis secondary to paclitaxel. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;23:170–1. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0b013e318032e908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Edelstein J, Reiss G. The wedge punctoplasty for treatment of punctal stenosis. Ophthalmic Surg. 1992;23:818–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fayet B, Bernard JA, Ammar J, Taylor Y, Bati E, Hurbi T, et al. Complications of punctum plug in the symptomatic treatment of dry eye. J Fr Ophtalmol. 1990;13:135–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fayet B, Koster H, Benabder Razik S, Bernard JA, Pouliquen Y. Six canalicular stenoses after 34 punctal plugs. Eur J Ophthalmol. 1991;1:154–5. doi: 10.1177/112067219100100310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fayet B, Benabderrazik S, Bernard JA, Deligne L, Hurbi T, D’Hermies F, et al. Canalicular stenoses complicating the insertion of lacrimal plugs: Incidence and mechanisms. J Fr Ophtalmol. 1992;15:25–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fayet B, Assouline M, Hanush S, Bernard J, D’Hermies F, Renard G. Silicone punctal plug extrusion resulting from spontaneous dissection of canalicular mucosa: A clinical and histopathologic report. Ophthalmology. 2001;108:405–9. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(00)00534-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shimizu K, Yokoi N, Kinoshita S. Fiberscopic observation of canaliculi after punctal plug extrusion. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2002;506:1285–8. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-0717-8_187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nelson CC. Complications of Freeman plugs. Arch Ophthalmol. 1991;109:923–4. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1991.01080070033019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maguire LJ, Bartley GB. Complications associated with the new smaller size Freeman punctal plug. Arch Ophthalmol. 1989;107:961–2. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1989.01070020023015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Horwath-Winter J, Thaci A, Gruber A, Boldin I. Long-term retention rates and complications of silicone punctal plugs in dry eye. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007;144:441–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2007.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Boldin I, Klein A, Haller-Schober EM, Howarth-Winter J. Long-term follow-up of punctal and proximal canalicular stenoses after silicone punctal plug treatment in dry eye patients. Am J Ophthalmol. 2008;146:968–72.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2008.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fiore PM, Jacobs IH, Goldberg DB. Drug-induced pemphigoid: A spectrum of diseases. Arch Ophthalmol. 1987;105:1660–3. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1987.01060120058023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brandt JD, Wittpenn JR, Katz LJ, Steinmann WN, Spaeth GL. Conjunctival impression cytology in patients with glaucoma using long-term topical medication. Am J Ophthalmol. 1991;112:297–301. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)76730-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Broadway DC, Grierson J, O’Brien C, Hitchings RA. Adverse effects of topical anti-glaucoma medication. Arch Ophthalmol. 1994;112:1437–45. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1994.01090230051020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sherwood MB, Grierson J, Millar L, Hitchings RA. Long-term morphologic effect of anti-glaucoma drug on the conjunctiva and tenon's capsule in glaucomatous patients. Ophthalmology. 1989;96:327–35. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(89)32888-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Herreras JM, Pastor JC, Calonge M, Asensio VM. Ocular surface alteration after long term treatment with an anti-glaucomatous drug. Ophthalmology. 1992;99:1082–8. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(92)31847-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pisella PJ, Pouliquen P, Baudouin C. Prevalence of ocular symptoms and signs with preserved and preservative free glaucoma medication. Br J Ophthalmol. 2002;86:418–23. doi: 10.1136/bjo.86.4.418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Van Buskirk EM. Side effects from glaucoma therapy. Ann Ophthalmol. 1980;23:964–65. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Smith DL, Skuta GL, Kincaid MC, Rabbani R, Cruess DF, Kao SF. The effects of glaucoma medications on tenon's capsule and conjunctiva in the rabbit. Ophthalmic Surg. 1991;22:336–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Munk PL, Lin DT, Morris DC. Epiphora: Treatment by means of dacryocystoplasty with balloon dilation of the nasolacrimal drainage apparatus. Radiology. 1990;177:687–90. doi: 10.1148/radiology.177.3.2243969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kashkouli MB, Pakdel F, Amani A, Asefi M, Aghai GH, Falavarjani KG. A modified Schirmer test in dry eye and normal subjects: Open versus closed eye and 1-minute versus 5-minute tests. Cornea. 2010;29:384–7. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e3181ba6ef3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mainville N, Jordan DR. Etiology of tearing: A retrospective analysis of referrals to a tertiary care ocuplastics practice. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;27:155–7. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0b013e3181ef728d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Narayanan K, Barnes EA. Epiphora with eyelid laxity. Orbit. 2005;24:201–3. doi: 10.1080/01676830500192126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kashkouli MB, Nilfroushan N, Nojomi M, Rezaee R. External lacrimal punctum grading: Reliability and interobserver variation. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2008;18:507–11. doi: 10.1177/112067210801800401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ma’luf RN, Hamush NG, Awwad ST, Noureddin B. Mitomycin C as adjunct therapy in correcting punctal stenosis. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;18:285–8. doi: 10.1097/00002341-200207000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Konuk O, Urgancioglu B, Unal M. Long-term success rate of perforated punctal plugs in the management of acquired punctal stenosis. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;24:399–402. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0b013e318185a9ca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fein W. Cautery applications to relieve punctal stenosis. Arch Ophthalmol. 1977;95:145–6. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1977.04450010145015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Awan KJ. Laser punctoplasty for the treatment of punctal stenosis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1985;100:341–2. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(85)90814-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dolin SL, Hecht SD. The punctum pucker procedure for stenosis of the lacrimal punctum. Arch Ophthalmol. 1986;104:1086–7. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1986.01050190144055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kashkouli MB, Beigi B, Astbury N. Acquired external punctal stenosis: Surgical management and long-term follow-up. Orbit. 2005;24:73–8. doi: 10.1080/01676830490916055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Offutt WN, 4th, Cowen DE. Stenotic puncta: Microsurgical punctoplasty. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 1993;9:201–5. doi: 10.1097/00002341-199309000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lam S, Tessler HH. Mitomycin as adjunct therapy in correcting iatrogenic punctal stenosis. Ophthalmic Surg. 1993;24:123–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bowman W. Methode de traitment applicable a’ l’epiphora dependent durenversement en dehors ou de l’obliteration des points lacrymaux. Ann Oculist. 1853;29:52–5. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Arlit F. Operationen an den Thränenwegen. In: Graefe A, Saemisch T, editors. Handbuch der gesammten Augenheilkunde. Leipzig: Verlag von Wilhelm Engelmann; 1874. pp. 479–80. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jones LT, Wobig JL. Surgery of the eyelids and lacrimal system. New York, NY: Aesculapius Publishers Inc; 1976. pp. 201–12. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Veirs ER. Lacrimal Disorders: Diagnosis and treatment. St Louis, Mo: CV Mosby; 1976. pp. 68–71. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bodian M. Repair of occluded lower canaliculus. Arch Ophthalmol. 1977;95:1839–40. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1977.04450100141020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chak M, Irvine F. Rectangular 3-snip Punctoplasty Outcomes: Preservation of the lacrimal pump in punctoplasty surgery. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;25:134–5. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0b013e3181994062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lüchtenberg M, Berkefeld J, Bink A. Presaccal stenosis as a cause of epiphora. Radiologe. 2008;48:1164–8. doi: 10.1007/s00117-008-1692-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Liarakos VS, Boboridis KG, Mavrikakis E, Mavrikakis I. Management of canalicular obstructions. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2009;20:395–400. doi: 10.1097/ICU.0b013e32832ec3e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Schittkowski MP, Guthoff RF. Results of lacrimal assessment in patients with congenital clinical anophthalmos or blind microphthalmos. Br J Ophthalmol. 2007;91:1624–6. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2007.120121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kashkouli MB, Rezaee R, Nilforoushan N, Salimi S, Foroutan A, Naseripour M. Topical antiglaucoma medications and lacrimal drainage system obstruction. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;24:172–5. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0b013e3181706829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kashkouli MB, Pakdel F, Hashemi M, Ghaempanah MJ, Rezaee R, Kaghaz-Kanani R, et al. Comparing anatomical pattern of topical anti-glaucoma medications associated lacrimal obstruction with a control group. Orbit. 2010;29:65–9. doi: 10.3109/01676830903324284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Esmaeli B, Amin S, Valero V, Adinin R, Arbuckle R, Banay R, et al. Prospective study of incidence and severity of epiphora and canalicular stenosis in patients with metastatic breast cancer receiving docetaxel. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3619–22. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.4453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kashkouli MB, Parvaresh MM, Mirzajani H, Astaraki A, Falavarjani KG, Ahadian A. Intraoperative mitomycin C use during filtration surgery and lacrimal drainage system obstruction. Am J Ophthalmol. 2009;147:453–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2008.08.037. e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yim JF, Crofts KP. Bilateral punctal-canalicular stenosis following photodynamic therapy for choroidal neovascularization. Cutan Ocul Toxicol. 2011;30:78–9. doi: 10.3109/15569527.2010.521221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Jones LT. The cure of epiphora due to canalicular disorders, trauma and surgical failures on the lacrimal passages. Trans Am Acad Ophthalmol Otolaryngol. 1962;66:506–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wormald PJ, Tsirbas A. Investigation and endoscopic treatment for functional and anatomical obstruction of the nasolacrimal duct system. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 2004;29:352–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2273.2004.00836.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Athanasiov PA, Prabhakaran VC, Mannor G, Woog JJ, Selva D. Transcanalicular approach to adult lacrimal duct obstruction: A review of instruments and methods. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging. 2009;40:149–59. doi: 10.3928/15428877-20090301-04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zoumalan CI, Maher EA, Lelli GJ, Jr, Lisman RD. Balloon canaliculoplasty for acquired canalicular stenosis. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;26:459–61. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0b013e3181eea303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Caversaccio M, Hausler R. Insertion of double bicanalicular silicone tubes after endonasal dacryocystorhinostomy in lacrimal canalicular stenosis: A 10-year experience. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec. 2006;68:266–9. doi: 10.1159/000093096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hwang SW, Khwarg SI, Kim JH, Choung HK, Kim NJ. Bicanalicular double silicone intubation in external dacryocystorhinostomy and canaliculoplasty for distal canalicular obstruction. Acta Ophthalmol. 2009;87:438–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.2008.01292.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Boboridis KG, Bunce C, Rose GE. Outcome of external dacryocystorhinostomy combined with membranectomy of a distal canalicular obstruction. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;139:1051–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2005.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Khoubian JF, Kikkawa DO, Gonnering RS. Trephination and silicone stent intubation for the treatment of canalicular obstruction: Effect of the level of obstruction. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;22:248–52. doi: 10.1097/01.iop.0000226863.21961.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Nemet AY, Wilcsek G, Francis IC. Endoscopic dacryocystorhinostomy with adjunctive mitomycin C for canalicular obstruction. Orbit. 2007;26:97–100. doi: 10.1080/01676830601174627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Yang SW, Park HY, Kikkawa DO. Ballooning canaliculoplasty after lacrimal trephination in monocanalicular and common canalicular obstruction. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2008;52:444–9. doi: 10.1007/s10384-008-0598-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Dutton JJ, Holck DE. Holmium laser canaliculoplasty. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 1996;12:211–7. doi: 10.1097/00002341-199609000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Rosenstock T, Hurwitz JJ. Functional obstruction of the lacrimal drainage passages. Can J Ophthalmol. 1982;17:249–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Demirci H, Elner VM. Double silicone tube intubation for the management of partial lacrimal system obstruction. Ophthalmology. 2008;115:383–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.03.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Couch SM, White WR. Endoscopically assisted balloon dacryoplasty treatment of incomplete nasolacrimal duct obstruction. Ophthalmology. 2004;111:585–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2003.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bleyen I, van den Bosch WA, Bockhholts D, Mulder P, Paridaens D. Silicone intubation with or without balloon dacryocystoplasty in acquired partial nasolacrimal duct obstruction. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007;144:776–80. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2007.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kielhorn I, Rowson NJ. Lateral canthal surgery in the management of epiphora. Orbit. 2002;21:111–6. doi: 10.1076/orbi.21.2.111.7184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Liu D. Conjunctivochalasis. A cause of tearing and its management. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 1986;2:25–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Mombaerts I, Colla B. Partial Lacrimal Carunculectomy A simple procedure for epiphora. Ophthalmology. 2001;108:793–7. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(00)00637-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Cheema MM, Meyer DR. Epiphora secondary to punctal apposition in the setting of Graves’ orbitopathy. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 1995;11:122–4. doi: 10.1097/00002341-199506000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wearne MJ, Pitts J, Frank J, Rose GE. Comparison of dacryocystoplasty and lacrimal scintigraghy in the diagnosis of functional nasolacrimal duct obstruction. Br J Ophthalmol. 1999;83:1032–5. doi: 10.1136/bjo.83.9.1032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kashkouli MB, Kempster RC, Galloway GD, Beigi B. Monocanalicular versus bicanalicular silicone intubation for nasolacrimal duct stenosis in adults. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;21:142–7. doi: 10.1097/01.iop.0000155524.04390.7b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Delaney YM, Khooshabeh R. External dacryocystorhinostomy for the treatment of acquired partial nasolacrimal obstruction in adults. Br J Ophthalmol. 2002;86:533–5. doi: 10.1136/bjo.86.5.533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Konuk O, Ilgit E, Erdinc A, Onal B, Unal M. Longterm results of balloon dacryocystoplasty: Success rates according to the site and severity of the obstruction. Eye (Lond) 2008;22:1483–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6702912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Connell PP, Fulcher TP, Chacko E, O’connor MJ, Moriarty P. Long term follow up of nasolacrimal intubation in adults. Br J Ophthlamol. 2006;90:435–6. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2005.084590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Zaidi FH, Symanski S, Olver JM. A clinical trial of endoscopic vs external dacryocystorhinostomy for partial nasolacrimal duct obstruction. Eye (Lond) 2011;25:1219–24. doi: 10.1038/eye.2011.77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kashkouli MB, Parvaresh MM, Modarreszadeh M, Hashemi M, Beigi B. Factors affecting the success of external dacyocystorhinostomy. Orbit. 2003;22:247–55. doi: 10.1076/orbi.22.4.247.17255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Fulcher T, O’connor M, Moriarty P. Nasolacrimal intubation in adults. Br J Ophthlamol. 1998;82:1039–41. doi: 10.1136/bjo.82.9.1039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Tripathi A, Lesser TH, O’Donnell NP, White S. Local anaesthetic endonasal endoscopic laser dacryocystorhinostomy: Analysis of patients’ acceptability and various factors affecting the success of this procedure. Eye (Lond) 2002;16:146–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6700083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Ishio K, Sugasawa M, Tayama N, Kaga K. Clinical usefulness of endoscopic intranasal dacryocystorhinostomy. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl. 2007;559:95–102. doi: 10.1080/03655230701597499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.More WM, Bentley CR, Olver JM. Functional and anatomic results after two types of endoscopic endonasal dacryocystorhinostomy: Surgical and holmium laser. Ophthalmology. 2002;109:1575–82. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(02)01114-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Lee JM, Song HM, Han YM, Chung GH, Sohn MH, Kim CS, et al. Balloon dacryocystoplast: Results in the treatment of complete and partial obstructions of the nasolacrimal system. Radiology. 1994;192:503–8. doi: 10.1148/radiology.192.2.8029423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Yazici Z, Yazici B, Parlak M, Erturk H, Savci G. Treatment of obstructive epiphora in adults by balloon dacryocystoplasty. Br J Ophthalmol. 1999;83:692–6. doi: 10.1136/bjo.83.6.692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Perry JD, Maus JD, Maus M, Nowinski TS, Penne TS, Penne RB. Balloon catheter dilation for treatment of adults with partial nasolacrimal duct obstruction. Am J Ophthalmol. 1998;126:811–6. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(98)00278-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Kashkouli MB, Beigi B, Tarassoly K, Kempster RC. Endoscopically assisted balloon dacryocystoplasty and silicone intubation versus silicone intubation alone in adults. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2006;16:514–9. doi: 10.1177/112067210601600402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Delcoigne C, Hennekes R. Probing and silicone intubation of the lacrimal system in adults. Bull Soc Belge Ophthalmol. 1994;254:63–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Ariturk N, Oge I, Oge F, Erkan D, Havuz E. Silicone intubation for obstruction of the nasolacrimal duct in adults. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 1999;77:481–2. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0420.1999.770429.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Fayet B, Bernard JA, Assouline M. Bicanalicular versus monocanalicular silicone intubation for nasolacrimal duct impotency in children: A comparative study. Orbit. 1993;12:149–56. [Google Scholar]

- 106.Frueh BR. Silicone intubation for the treatment of congenital lacrimal duct obstruction: Successful results removing the tubes after six weeks [discussion] Ophthalmology. 1988;95:795. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(88)33122-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Bell TA. An investigation into the efficacy of probing the nasolacrimal duct as a treatment for epiphora in adults. Trans Ophthalmol Soc UK. 1986;105:494–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Liu D, Stasior OG. Lower eyelid laxity and ocular symptoms. Am J Ophthalmol. 1983;95:545–51. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(83)90279-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Vick VL, Holds JB, Hartstein ME, Masry GG. Tarsal strip procedure for the correction of tearing. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;20:37–9. doi: 10.1097/01.IOP.0000103005.81708.FD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]