Abstract

Pars plana vitrectomy is an established surgical method for the treatment of proliferative diabetic retinopathy and its complications. Anti-vascular endothelial growth factor agents suppress vascular proliferation and may be used as pharmacological adjuvants to reduce the incidence of postoperative hemorrhage in the vitreous cavity and to facilitate the surgical approach. We conducted an electronic search to identify prospective randomized controlled trials looking at the use of —perioperative vascular endothelial growth factor suppression in diabetic patients undergoing vitrectomy. We found six prospective randomized trials with only one being double-masked. We present a summary of the findings. Four studies suggest that the use of perioperative, anti-vascular endothelial growth factor agents facilitate vitrectomy surgery, but only one study supports their use to reduce the chances of early postoperative vitreous bleeding. Two studies did not find a significant benefit for their use before surgery to reduce the recurrence of vitreous hemorrhage in proliferative diabetic retinopathy. More randomized double blinded studies with a larger number of patients are needed to establish a clear recommendation regarding the use of these agents. Those studies should factor in the use of endo-tamponade with gas or silicone oil following vitrectomy.

Keywords: Anti-Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor, Diabetic Retinopathy, Vitrectomy

INTRODUCTION

Vitrectomy surgery has emerged as a cornerstone for treatment of proliferative diabetic retinopathy and its complications. Advances in surgical techniques and equipment continue to evolve and shape up the future of this modality of treatment. The use of anti- vascular endothelial growth factor (anti-VEGF) agents as an adjuvant pharmacotherapy in the perioperative period has been proposed to provide better surgical outcomes. These agents reduce the vascularity of neovascular tissues and inhibit vascular proliferation,1 which will conceptually provide a better view for the surgeon and lower the chances of vitreous cavity hemorrhage following the procedure. This review will address the use and efficacy of anti-VEGFs in the perioperative period in diabetic vitrectomy and will scrutinize the available data on this issue.

We searched PubMed, MEDLINE, EMBASE, CENTRAL and LILACS for all trials that looked at the use of anti-VEGFs in the perioperative period for diabetic vitrectomy. Randomized prospective studies were identified and reviewed.

Background

Pars plana vitrectomy (PPV) is an important modality to treat proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR). In one report, PPV was required in up to 10% of patients presenting with PDR within one year.2 The most common indications for surgery are nonclearing vitreous hemorrhage (VH), tractional retinal detachments (TRDs) threatening the macula and combined tractional/rhegmatogenous detachments.3 A significant and rather common complication is vitreous cavity hemorrhage which may range from 10 to 80% of cases.4 This hemorrhage can either be early (present within the first postoperative days) or late, recurring within two to six months after a clear vitreous cavity postoperatively.

Causes of early or persistent hemorrhage include:

Remnants of new vessels or oozing dissected tissues during or after surgery

Sclerotomy site bleeding

Blood clot lysis

Hemorrhage from residual anterior vitreous “shake out bleeding”.

Late or recurrent hemorrhage can result from:

New vessel growth

Recurrent traction on remnant dissected tissue

Entry site neovascularization5 in which new anterior vessels grow at the inner sclerotomy sites accompanied with traction. This occurrence can be visualized by indirect ophthalmoscopy with deep scleral depression or documented with anterior segment high resolution ultrasonography.6

Management of this complication ranges from observation7 to timely revision surgery. This depends on a number of factors including the status of the eye, the status of the fellow eye and the general condition of the patient. It is estimated that 30 to 50% of patients with postoperative vitreous hemorrhage would need revision surgery.8

Management of postoperative vitreous cavity bleeding and the proposed role of Anti-VEGFs

A number of surgical strategies are considered the standard of clinical care and are aimed to prevent the occurrence of postoperative vitreous cavity hemorrhage. Achieving adequate hemostasis, removal of posterior vitreo-retinal traction and aggressive panretinal photocoagulation treatment are widely adopted surgical principles. Cryotherapy or laser to the sclerotomy site is thought to inhibit entry-site neovascularization.9 Identifying the true vitreo-retinal plane and eliminating recurrent traction is crucial to prevent neovascularization. Physical agents like air, gas and silicone oil play an important role as tamponade agents and therefore reduce the incidence of postoperative bleeding.

Pharmacological agents such as triamcinolone have been used intra-operatively to reduce inflammation and vascular proliferation.10 Oral tranexamic acid has been given to patients after vitrectomy for PDR to inhibit clot dissolution and fibrinolysis.11 Anti-VEGF therapy has become the standard of care in many ophthalmic conditions, and is considered an important modality for treatment of diabetic macular edema. VEGF suppression pre- and intra-operatively12 has been used to reduce neovascularization. This review aims to put the information regarding this modality into perspective.

Methods

Studies considered for review

An electronic search was performed last on December 8th 2011 to identify studies that addressed the use of anti-VEGFs in the perioperative period to reduce bleeding in patients undergoing vitrectomy for PDR. The patients had to be undergoing their first vitrectomy. A total of 96 records were screened after eliminating duplicates.

After excluding irrelevant and retrospective reports, 6 prospective randomized studies were identified. We will highlight the characteristics of these randomized studies and aim to draw conclusions based on each study design. The different methodology used in those studies precludes a meta-analysis.

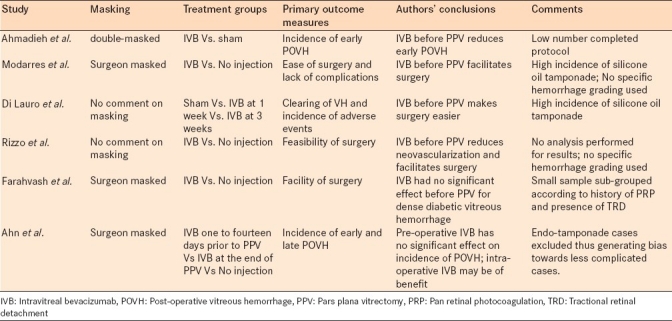

Table 1 summarizes the six clinical trials in terms of characteristics and results.

Table 1.

Summary of the six randomized prospective clinical trials with pertinent characteristics and results

The only double-masked prospective randomized clinical trial comes from Iran, where Ahmadieh et al randomized 68 eyes of 68 patients undergoing PPV for PDR.13 Thirty five eyes received 1.25mg of intravitreal bevacizumab (IVB) one week prior to surgery while 33 received sham injections. The study clearly randomized and allocated patients into the treatment and control group and it accounts for participants who failed to complete the study protocol.

The primary outcome measure in this study was the incidence of early postoperative vitreous hemorrhage (defined as occurring before or at 4 weeks after surgery). Secondary outcomes included mean change in best corrected visual acuity (BCVA) and injection related adverse events. Follow up was at 1 day, 1 week and 1 month after surgery.

The authors reported the outcomes based on the intention to treat analysis and the per-protocol analysis. In the intention-to-treat analysis, the incidence of postvitrectomy hemorrhage 1 week and 1 month after surgery was significantly lower in the treatment group compared with the control group (P = 0.023 and P = 0.001, respectively). Mean BCVA improved from 1.88 logarithm of minimum angle of resolution (logMAR) units in both study groups before surgery to 0.91 logMAR units and 1.46 logMAR units 1 month after vitrectomy in the treatment and control groups, respectively (P= 0.001). The authors reported no significant local or systemic injection related complications. Only one participant developed ocular hypertension after vitrectomy.

The per-protocol analysis included 16 eyes in the treatment group and 18 eyes in the control group. Postvitrectomy hemorrhage occurred less frequently 1 week and 1 month after surgery in the IVB group compared with the control group (P = 0.033 and P = 0.003, respectively). Mean improvement in BCVA 1 month after vitrectomy was -1.05 logMAR units in the IVB group and -0.42 logMAR units in the control group (P = 0.004).

The main reasons for not completing this study protocol were reabsorption of the vitreous hemorrhage before surgery (9 patients) and the use of silicone oil tamponade (6 patients).

Modarres et al undertook a prospective surgeon-masked randomized clinical trial where 40 eyes of 40 diabetic patients were given either an IVB injection of 2.5mg 3 to 5 days before operation or no injection at all.14 No details of the randomization methods used were presented by the authors. The surgeons were masked but no details were available regarding masking the study personnel. The study looked at the facilitation of surgery as a primary endpoint (including the duration of surgery, number of endodiathermy applications and number of backflush needle applications). Mean surgical time was 62+/-57.3 minutes in the injected group versus 95.5+/-36 minutes in the noninjected group (P=0.03). Endodiathermy applications 6.0+/-4.3 versus 11.0+/-5.8 (P=0.004). Backflush cannula applications 11.0+/-7.2 versus 18.1+/-7.8 (P=0.004). Visual and anatomic outcomes at 6 months were the secondary outcome measures. Postoperative visual acuities were significantly better than preoperative visual acuities. Preoperative and 3-month postoperative visual acuities were the same for both groups. In the last follow-up examinations (mean 7+/- 3.6 months), the injected group had better visual acuities than the noninjected group (1.1+/-0.4 and 1.4+/-0.3 logMAR, respectively, P=0.006). This study had a high rate of silicone oil tamponade (10/22 in the treatment group and 7/18 in the control group).

Di Lauro et al conducted a prospective randomized clinical trial on 72 eyes of 68 participants who required vitrectomy for PDR.15 This study had three treatment groups: Group A received sham injections; group B received 1.25 mg of bevacizumab one week before vitrectomy; and group C received 1.25 mg of bevacizumab 3 weeks before the surgery. The authors did not comment on the randomization or sequence of allocation of participants and there were no comments on the masking of participants or investigators. The primary outcome measures were the clearing of vitreous hemorrhage, the incidence of adverse effects and the need for other procedures during surgery. The average difference in the surgical time was statistically significant between group A and group B (P = 0.025), and between group A and group C (P = 0.031). Again this study had a high rate of silicone oil tamponade (33.3% overall) and those patients were not excluded in the statistical analysis.

Rizzo et al preformed an interventional, consecutive, randomized prospective study on 22 eyes of 22 participants.16 The treatment group received 1.25 mg of IVB 5 to 7 days prior to PPV and the control group received PPV alone. Again there was no comment on masking. The authors used a table of random numbers to assign each participant to a study group. The primary outcome was the feasibility of surgery but no analysis was undertaken. Visual acuity at six months was analyzed as a secondary outcome. There was no direct comment on the rate of postoperative bleeding. The authors concluded that IVB before PPV reduces neovascularization and facilitates surgery.

Farahvash and collaborators randomized 35 eyes of 35 patients undergoing PPV for dense diabetic vitreous hemorrhage.17 Despite the less number of patients, both groups were divided into 4 subgroups according to patient characteristics, mainly history of pan retinal photocoagulation (PRP) and the presence of TRD. Eighteen eyes received 1.25mg of IVB one week prior to surgery versus 17 in the control group who received nothing and were considered the control group. An intraoperative complexity score and PDR stage were recoded to compare the complexity of both groups. Surgeons were masked to the groups and subgroups.

The primary outcome measures in this study were the facility of surgery (severity of intraoperative bleeding and break formation, quantified by a surgeon based scoring system) and the incidence of early and/ or late postoperative vitreous hemorrhage (defined as occurring before or after 4 weeks of surgery, respectfully). Secondary outcomes included mean change in (BCVA) and injection related adverse events. Follow up was 1 day, 1 week and 1 month and every 3 months after surgery.

The mean scores of postoperative bleeding between the two groups were not significantly different (P=0.35), nor were the endodiathermy applications and break formations. Anatomical outcome and visual acuity at three months and at the final follow up visit were also similar.

Limitations of this study include the use of endotamponade in 9 patients and the lack of evaluation of induction or progression of TRD by ultrasonography. The surgeries were done by three different surgeons and this might be of significance given the small sample size.

The largest prospective randomized clinical trial to date comes from Korea where Ahn et al randomly assigned 107 eyes of 91 patients to three groups: group 1 received 1.25 mg IVB injection 1 to 14 days before PPV for PDR related complications. Group 2 received the same injection at the end of surgery and group 3 got no injection.18

The primary outcome was the incidence of early (less or equal to 4 weeks) and late (more than 4 weeks) recurrent VH. Secondary outcome measures were the initial time of vitreous clearing (ITVC) and BCVA at 6 months after surgery.

The incidences of early recurrent VH were 22.2, 10.8 and 32.4% in groups 1, 2 and 3 respectively (P=0.087). A subgroup pairwise analysis showed significantly decreased early VH incidence in group 2 compared to that of group 3 (P=0.026). The ITVC was significantly shorter in group 2 when compared with groups 1 and 3 (P=0.45 and P=0.015, respectfully). The BCVA at 6 months postoperatively did not differ significantly between the three groups.

This study included a good number of patients but was not double masked. The period in which IVB was injected was variable (1-14 days) nor were sham injections performed. All cases which needed endo-tamponade were excluded from the study, which introduces a possible bias towards including less complicated PDR patients. The researchers point out that the proportion of those patients where similar among the three groups and their inclusion did not alter the main outcomes of the study, but no data is provided.

The authors therefore found no evidence to support the use of preoperative IVB to reduce the recurrence of VH in vitrectomy for PDR but maintained that in some cases, its intraoperative use may be of benefit. They recommend a multicenter prospective trial with still a larger number of patients to obtain more conclusive evidence.

CONCLUSION

The use of preoperative IVB has been shown to reduce the incidence of postoperative vitreous hemorrhage in one randomized double blind prospective study (Ahmadieh et al),13 although the number of patients who completed the protocol was small. A prospective randomized (but not double blind) trial by Ahn and collaborators18 maintained that preoperative IVB had no significant effect on postoperative bleeding but reported that intra-operative injections may be of added benefit. Other randomized (and nonrandomized) trials that looked at different outcome measures produced inconclusive recommendations. Using Anti-VEGFs in the perioperative period for diabetic vitrectomy may offer certain advantages but multicenter double masked, prospective studies should address the occurrence of early and late vitreous cavity bleeding as primary end points, with clear grading of the hemorrhage based on established criteria (e.g. diabetic vitrectomy study criteria). The studies should also incorporate the effects of using endo-tamponade with gas or silicone oil on the statistical analysis of the data.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Research to Prevent Blindess, New York, NY

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Smith JM, Steel DH. Anti-vascular endothelial growth factor for prevention of postoperative vitreous cavity haemorrhage after vitrectomy for proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011:CD008214. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008214.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaiser RS, Maguire MG, Grunwald JE, Lieb D, Jani B, Brucker AJ, et al. One-year outcomes of panretinal photocoagulation in proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Am J Ophthalmol. 2000;129:178–85. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(99)00322-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ho T, Smiddy WE, Flynn HW., Jr Vitrectomy in the management of diabetic eye disease. Surv Ophthalmol. 1992;37:190–202. doi: 10.1016/0039-6257(92)90137-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Virata SR, Kylstra JA. Postoperative complications following vitrectomy for proliferative diabetic retinopathy with sewon and noncontact wide-angle viewing lenses. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers. 2001;32:193–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.West JF, Gregor ZJ. Fibrovascular ingrowth and recurrent haemorrhage following diabetic vitrectomy. Br J Ophthalmol. 2000;84:822–5. doi: 10.1136/bjo.84.8.822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Steel DH, Habib MS, Park S, Hildreth AJ, Owen RI. Entry site neovascularization and vitreous cavity hemorrhage after diabetic vitrectomy. The predictive value of inner sclerostomy site ultrasonography. Ophthalmology. 2008;115:525–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.08.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tolentino FI, Cajita VN, Gancayco T, Skates S. Vitreous hemorrhage after closed vitrectomy for proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Ophthalmology. 1989;96:1495–500. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(89)32700-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blankenship GW. Management of vitreous cavity hemorrhage following pars plana vitrectomy for diabetic retinopathy. Ophthalmology. 1986;93:39–44. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(86)33791-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yeh PT, Yang CM, Yang CH, Huang JS. Cryotherapy of the anterior retina and sclerotomy sites in diabetic vitrectomy to prevent recurrent vitreous hemorrhage: An ultrasound biomicroscopy study. Ophthalmology. 2005;112:2095–102. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2005.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Faghihi H, Taheri A, Farahvash MS, Esfahani MR, Rajabi MT. Intravitreal triamcinolone acetonide injection at the end of vitrectomy for diabetic vitreous hemorrhage: A randomized, clinical trial. Retina. 2008;28:1241–6. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e31817d5be3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ramezani AR, Ahmadieh H, Ghaseminejad AK, Yazdani S, Golestan B. Effect of tranexamic acid on early postvitrectomy diabetic haemorrhage: A randomised clinical trial. Br J Ophthalmol. 2005;89:1041–4. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2004.062638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Romano MR, Gibran SK, Marticorena J, Wong D, Heimann H. Can an intraoperative bevacizumab injection prevent recurrent postvitrectomy diabetic vitreous hemorrhage? Eur J Ophthalmol. 2009;19:618–21. doi: 10.1177/112067210901900416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ahmadieh H, Shoeibi N, Entezari M, Monshizadeh R. Intravitreal bevacizumab for prevention of early postvitrectomy hemorrhage in diabetic patients: a randomized clinical trial. Ophthalmology. 2009;116:1943–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Modarres M, Nazari H, Falavarjani KG, Naseripour M, Hashemi M, Parvaresh MM. Intravitreal injection of bevacizumab before vitrectomy or proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2009;19:848–52. doi: 10.1177/112067210901900526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.di Lauro R, De Ruggiero P, di Lauro R, di Lauro MT, Romano MR. Intravitreal bevacizumab for the surgical treatment of severe proliferative retinopathy. Graefe's Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2010;248:785–91. doi: 10.1007/s00417-010-1303-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rizzo S, Genovesi-Ebert F, Di Bartolo E, Vento A, Miniaci S, Williams G. Injection of intravitreal bevacizumab (Avastin) as a preoperative adjunct before vitrectomy surgery in the treatment of severe proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR) Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2008;246:837–42. doi: 10.1007/s00417-008-0774-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Farahvash MS, Majidi AR, Roohipoor R, Ghassemi F. Preoperative injection of intravitreal bevacizumab in dense diabetic vitreous hemorrhage. Retina. 2011;31:1254–60. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e31820a68e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ahn J, Woo SJ, Chung H, Park KH. The effect of adjunctive bevacizumab for preventing postvitrectomy hemorrhage in proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Ophthalmology. 2011;118:2218–26. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]