Abstract

Vertebrate Dlx genes have been implicated in the differentiation of multiple neuronal subtypes, including cortical GABAergic interneurons, and mutations in Dlx genes have been linked to clinical conditions such as epilepsy and autism. Here we show that the single Drosophila Dlx homolog, distal-less, is required both to specify chemosensory neurons and to regulate the morphologies of their axons and dendrites. We establish that distal-less is necessary for development of the mushroom body, a brain region that processes olfactory information. These are important examples of distal-less function in an invertebrate nervous system and demonstrate that the Drosophila larval olfactory system is a powerful model in which to understand distal-less functions during neurogenesis.

Keywords: amos, antennal lobe, atonal, dorsal organ

Although the distal-less (dll) gene is best known for its conserved role in limb patterning, its homologs play essential roles in vertebrate neural development (reviewed in ref. 1). Indeed, it has been proposed that the ancestral role for dll was in some aspect of neural development (2). Consistent with this hypothesis, four of the six mammalian Dlx genes play essential roles in embryonic neural development, including development of multiple components of the olfactory system. Three Dlx genes also are required for neurogenesis in regenerating components of the adult olfactory epithelium and the olfactory bulb. However, outside of the vertebrate lineage, the role of dll in olfaction has not been examined. Given the biological importance of olfaction and its lengthy evolutionary history, we hypothesized that dll also plays significant roles in the developing invertebrate olfactory system and tested this idea in the genetically tractable model Drosophila melanogaster.

Most previous studies of Drosophila olfaction have been carried out with the adult. However, the larval system represents a substantially simpler model in which to dissect neural development and wiring (reviewed in ref. 3). In addition, portions of the larval olfactory system serve as templates for corresponding structures in the adult, forming during embryogenesis, growing during the larval instars, and being remodeled during metamorphosis. Thus, elucidating the earliest events in the specification and differentiation of larval olfactory receptor neurons (ORNs) and olfactory information processing centers is highly relevant to later development. We therefore asked whether dll was required for the differentiation of larval ORNs or other larval neurons required for relaying or processing of olfactory information.

The larval Drosophila olfactory organ is called the dorsal organ (DO; Fig. 1A). The DO is of mixed modalities, mediating part of the gustatory response as well as all of the olfactory response (reviewed in refs. 3 and 4). The DO consists of 21 ORNs, 15 gustatory receptor neurons (GRNs), and 42 support cells (reviewed in ref. 4). Each ORN possesses a single dendrite that innervates a domelike cuticular structure. The 21 ORN dendrites are clustered into seven triplets. Each ORN also possesses a single axon that projects to a distinct glomerulus of the larval antennal lobe (LAL) (Fig. 1A). The LAL consists of 21 glomeruli and their associated local interneurons and projection neurons (5, 6). From the LAL, projection neurons relay olfactory information to the mushroom body (MB) and the lateral horn (reviewed in refs. 3 and 4). In adults, the MB plays roles in the regulation of sleep, locomotion, male courtship behavior, and learning, including olfactory learning (7–12).

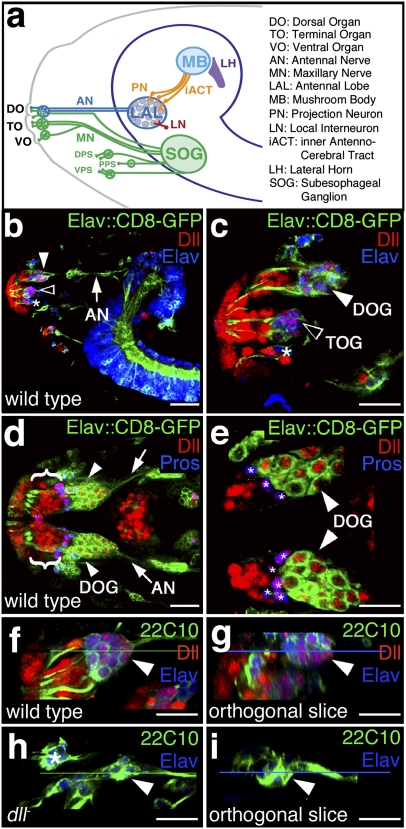

Fig. 1.

dll is expressed in neurons and associated support cells during larval olfactory system development and is required for neuronal development. (A) Schematic of the larval chemosensory system (adapted from ref. 3). Neurons in the DOG, TOG, and VO ganglion (VOG) and the dorsal, posterior, and ventral pharyngeal sense organs (DPS, PPS, and VPS) respond to chemical compounds encountered in the environment and relay chemosensory information to target areas in the central nervous system. ORNs in the DOG (white arrowheads in B–D) send afferent projections via the antennal nerve (AN; arrows in B and D) to the LAL where they form glomeruli connected by local interneurons (LNs). Projection neurons (PNs) of the LAL relay information via the inner antennocerebral tract (iACT) to brain areas associated with learning and memory: the lateral horn (LH) and MB. MN, maxillary nerve. (B and C) Lateral views at low (B) and high (C) magnification of a stage 16 elav-GAL4;UAS-mCD8-GFP Drosophila embryo stained for Dll (red) and the neuronal marker for embryonic lethal, abnormal vision (Elav; blue). GFP is localized to the membranes of neurons. Dll expression is detected in the DOG (white arrowheads in B and C), the TOG (open arrowheads in B and C), and the VOG (asterisk in C) as well as in support cells and epidermal cells. (D and E) Dorsal views at low (D) and high (E) magnification of a stage 16 elav-GAL4;UAS-mCD8-GFP Drosophila embryo stained for Dll (red) and Pros (blue). Dll is detected in DO neurons (white arrowheads in D and E) as well as the socket, sheath, and shaft support cells (brackets in D). Dll and Pros colocalize in sheath cells (purple; asterisks in E). (F–I) Dorsal views of stage 16 30wild-type (F and G) and dll-null (H and I) embryos stained for sensory neurons (monoclonal antibody 22C10; green), Dll (red), and Elav (blue). The wild-type DOG (arrowheads in F and G) consists of ∼36 neurons (21 ORNs plus ∼15 GRNs), whereas dll-null embryos (arrowheads in H and I) have an average of 7 DOG neurons. Orthogonal slices through the corresponding confocal Z-series are shown in G and I. The horizontal green lines in F and H represent the planes of section for G and I. The horizontal blue lines in G and I represent the depths within each Z-series of the images shown F and H. The asterisk in H marks neurons that are not part of the DO. Absence of Dll staining was used to identify dll-null embryos. Anterior is to the left in all images. (B–F and H) Optical sections (0.4 μm) were collected with a 40× objective. (C, E, F, and H) A 1.25× digital zoom was used. (Scale bars: 50 mm.)

Both the DO and the LAL to which it sends olfactory information arise from cells in the embryonic antennal segment. Fourteen sense organ precursors (SOPs) contribute to the DO (13). Seven of these give rise to the olfactory portion of the DO, and seven are gustatory. Relatively few genes have been identified to date that function during DO development. These include three basic helix–loop–helix (bHLH) transcription factor-encoding proneural genes: atonal (ato), absent multidendritic neurons and olfactory sensilla (amos), and scute (sc) (13). Specification of four of the olfactory SOPs requires ato while three require amos, and the DO gustatory SOPs are specified by sc (13). The cephalic gap genes orthodenticle (otd), empty spiracles (ems), and buttonhead (btd), which are coexpressed in the antennal head segment, also are required for DO development. Individual otd, ems, and btd mutants lack both cuticular and neuronal components of the DO (14). dll is downstream of otd, ems, and btd (15), and the cuticular components of the DO and terminal organ (TO) are missing in dll-null embryos (ref. 16 and this work). Here, we show that the neuronal components of DO also are defective in dll mutants and propose that dll is a key effector of cephalic gap gene function during DO development.

The MB arises from the embryonic labral and ocular segments. Four neuroblasts on either side of the brain serve as MB stem cells, proliferating throughout embryonic, larval, and pupal life to give rise to the hundreds of larval and thousands of adult MB neurons called Kenyon cells (17, 18). The dendrites and axon collaterals of the Kenyon cells cluster in the MB calyces, along with afferents from the ORNs. Kenyon cell axons form a large tract called the peduncle (reviewed in ref. 19). Although the genes that specify MB precursors remain unknown, both an orphan nuclear receptor encoded by the tailless (tll) gene and a transcription factor encoded by the Drosophila Pax6 homolog eyeless (ey) are required during the larval instars for proliferation of MB neuroblasts (20, 21). In addition, ey and a transcription factor encoded by dachshund (dac) are expressed in embryonic MB neuroblasts and required to establish the axon tracts of the MB (21–24).

Here, we establish that dll is expressed during the initial stages of olfactory system development and that dll mutants have strong phenotypes in the Drosophila larval olfactory system. The DO phenotypes are more severe than those of other genes required for ORN development and include the loss of most ORNs. We also observe defects in MB neuron differentiation in dll mutants. Because of the severity of the defects and their early onset, it is likely that dll acts near the top of the genetic hierarchy governing DO development. In addition, dll continues to be expressed in neurons and support cells that constitute the DO, and behavioral assays indicate that dll functions in postmitotic ORNs to mediate larval olfactory behavior. The findings presented here provide support for a fundamental role for dll in invertebrate neural development and neuronal function. Importantly, because the defects are reminiscent of those observed in Dlx mutant mice, these results indicate that dll/Dlx may play similar roles in the invertebrate and vertebrate olfactory systems.

Results

dll Is Expressed During the Development of Peripheral and Central Components of the Larval Chemosensory System.

Using immunohistochemical staining and confocal microscopy, we have characterized dll expression during the development of the larval chemosensory system. The larval chemosensory system is specified and differentiates during embryogenesis and is fully formed by hatching (13, 25, 26). dll is expressed in the developing larval chemosensory organs throughout embryogenesis (Fig. 1 B–E and Fig. S1 A–A′′) from the specification of sensory organ precursors (Fig. S1 A–A′′′) into the three larval instars (third instar, Fig. S1 B and C). During sense organ specification, dll is coexpressed with the proneural gene ato and the zinc-finger transcription factor senseless (sens) in the antennal, maxillary, and labial head segments (Fig. S1 A–A′′′).

The larval Drosophila chemosensory system consists of three paired external cephalic chemosensory organs (reviewed in refs. 3 and 4) and three pairs of internal gustatory pharyngeal sensilla: the dorsal, ventral, and posterior pharyngeal sense organs (DPS, VPS, and PPS, respectively, in Fig. 1A). dll is expressed in all of these (e.g., Fig. 1 B–E). In the cephalic chemosensory organs, dll is expressed in neurons, support cells (sheath, socket, and shaft cells), and associated epidermal cells (Fig. 1 B–E). We also found that dll is expressed in the cephalic neuroectoderm early in embryonic development in precursors of the protocerebrum and deutocerebrum, which give rise to the MB and antennal lobe, respectively (Fig. S1 A–A′′′).

dll Function Is Necessary for Normal Larval Olfactory Behavior.

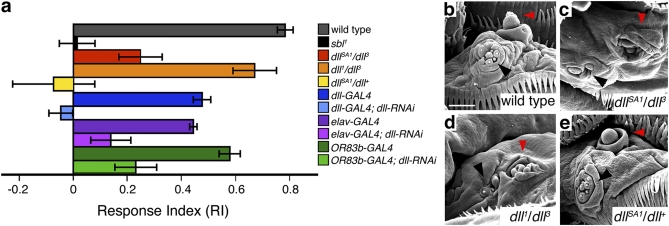

The expression of dll in chemosensory structures suggested that dll may be required for normal olfaction. However, dll-null animals die at the end of embryogenesis (16), before their olfactory responses can be assayed. We therefore tested third-instar larvae carrying multiple hypomorphic combinations of dll alleles in an olfactory behavioral assay (Fig. 2A and Fig. S2). The behavioral responses of dll mutants to an attractive odorant [1 μL of undiluted ethyl acetate (EtOAc)] were compared with those of wild-type and anosmic [smellblind (sbl)] larvae (27, 28). The severity of the behavioral phenotype varied depending on the allelic combination, and not all hypomorphic combinations resulted in behavioral deficits. Data for two of the six allelic combinations that demonstrated statistically significant impairments (P < 0.001) are shown (Fig. 2A). We note that all of these combinations exhibited relatively normal motor activity. Thus, the impairments are not caused by the inability to move. Consistent with this finding, allowing more time for the animals to reach the target zone (10 min instead of 5 min) did not change the response indices (RIs). The DO dome is a perforated cuticular structure filled with dendritic arborizations from underlying ORNs. ORNs provide afferent input to CNS structures, which in turn direct behavioral responses to chemical cues. Consequently, cuticular malformations would be likely to impair behavioral responses to odorants in larval behavioral assays. Consistent with this idea, dllSA1/dll3 larvae have DO cuticular malformations (Fig. 2 B and C) and display significant impairments in behavioral assays (Fig. 2A, red histogram). However, comparison of scanning electron micrographs and behavioral data revealed that normal behavioral responses occur in some dll hypomorphs despite cuticular malformations, whereas impaired responses can occur in the absence of cuticular malformations. For instance, in dll1/dll3 larvae, the DO dome is malformed (Fig. 2D), but larvae still respond to an attractive odorant (Fig. 2A, orange histogram). In contrast, olfaction is significantly impaired in dllSA1/dll+ larvae (Fig. 2A, yellow histogram) despite the proper formation of cuticular components of the DO (Fig. 2E). The DO dome also appears normal in dll-GAL4;UAS-dll-RNAi larvae, which show olfactory deficits (Fig. 2A, blue histograms), indicating that reduced dll function might affect the neural components of the olfactory system. Indeed, as described below, we have discovered defects in both the function and the development of olfactory system neurons in dll mutants.

Fig. 2.

dll mutants exhibit olfactory deficits in larval behavioral assays. (A) Olfactory RIs of dll mutants and dll-RNAi animals. See SI Materials and Methods for details of the assay. Data are plotted as mean ± SEM. With Student's two-tailed t test, P values <0.001 were obtained for dllSA1/dll3 (red histogram) and dllSA1/dll+ (yellow histogram) compared with wild type (gray histogram). Anosmic (sbl; black histogram) larvae served as a positive control. We also tested the responses of third-instar larvae in which UAS-dll-RNAi was driven by a pan-neural GAL4 driver (elav-GAL4; light purple histogram), an ORN-specific driver (OR83b-GAL4; light green histogram), or the dll-GAL4 driver (light blue histogram). Animals carrying any of the GAL4 drivers exhibited significant (P < 0.001) impairments in their olfactory behavioral responses even without the dll-RNAi construct present [dll-GAL4 (dark blue histogram), RI = 0.52 ± 0.08; elav-GAL4 (dark purple histogram), RI = 0.49 ± 0.02; and OR83b-GAL4 (dark green histogram), RI = 0.58 ± 0.04]. Nonetheless, when the dll-RNAi construct was present, the responses were significantly worse than with the respective GAL4 drivers alone (P < 0.05 for elav-GAL4 driving dll-RNAi and P < 0.001 for either OR83b-GAL4 or dll-GAL4 driving dll-RNAi). dll-GAL4 driving dll-RNAi (light blue histogram), RI = −0.05 ± 0.05; elav-GAL4 driving dll-RNAi (light purple histogram), RI = 0.15 ± 0.08; and OR83b-GAL4 driving dll-RNAi (light green histogram), RI = 0.25 ± 0.05. (B–E) Scanning electron micrographs (1,200×) of third-instar larval DO (red arrowheads) and TO (black arrowheads) from wild-type (B), dllSA1/dll3 (C), dll1/dll3 (D), and dllSA1/dll+ (E) heads. dllSA1/dll3 larvae have malformations in the DO dome (C) and display significant impairments in behavioral assays (RI = 0.27 ± 0.03; red histogram in A). The DO dome is also malformed in dll1/dll3 larvae (C), but larvae still respond well to the attractive odorant (RI = 0.72 ± 0.09; orange histogram in A). In contrast, olfaction is significantly impaired in dllSA1/dll+ larvae (RI = −0.08 ± 0.16; yellow histogram in A) despite the proper formation of the cuticular components of the DO and TO (E). Anterior is at the top, and ventral midline is to the right. (Scale bar: 50 mm.)

For instance, when a dll-RNAi construct is used to knock down dll activity, specifically in neurons, there are severe deficits in olfactory behaviors. Both elav-GAL4;UAS-dll-RNAi larvae, in which the dll-RNAi construct is expressed in both central and peripheral neurons (Fig. 2A, purple histograms), and OR83b-GAL4;UAS-dll-RNAi larvae, in which the dll-RNAi construct is expressed in ORNs (Fig. 2A, green histograms), show significant impairments in olfactory behavioral responses compared with each GAL4 driver alone. We also used a dll-GAL4 driver to express the dll-RNAi construct earlier and more broadly in the larval olfactory system. The dll-GAL4;UAS-dll-RNAi larvae (Fig. 2A, blue histograms) exhibit a greater impairment in our assays than either elav-GAL4;UAS-dll-RNAi or OR83b-GAL4;UAS-dll-RNAi animals do. Because dll-GAL4 drives expression in support cells associated with the DO, loss of dll function in these cells may contribute to the stronger behavioral impairment. Alternatively, and not mutually exclusively, because the dll-GAL4 driver is active in DO precursors and in developing brain regions, including the MB anlagen, the dll-GAL4;UAS-dll-RNAi behavioral phenotype may reflect a requirement for dll function during early developmental events such as the specification and differentiation of DO and/or MB precursors.

Loss of dll Function Disrupts the Development of the DO Ganglion (DOG).

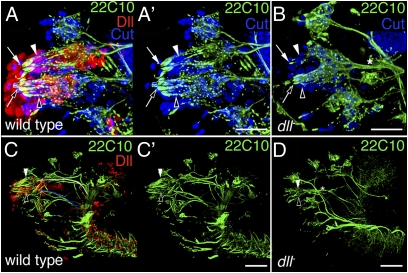

dll-null embryos have fewer neurons (Fig. 1 F–I) and fewer support cells (Fig. 3 A and B) than wild-type animals do in both the DO and the TO. The wild-type DO contains 36 neurons, comprising 21 ORNs plus 15 GRNs. However, an average of only seven neurons is found in dll-null embryos (n = 10). Thus, both ORNs and GRNs are compromised. However, no ectopic TUNEL staining is observed in these embryos, suggesting that the reduction in neuron number is occurring via reduced specification or proliferation of precursors. In addition, the remaining neurons exhibit aberrant morphologies. Specifically, the DO dendrites are loosely associated rather than tightly bundled (Fig. 3 C and D and Fig. S3 A–B′), and the axons of the remaining DO neurons project toward the subesophageal ganglion (SOG) (Fig. 3 C and D). This finding is consistent with GRN identity in that DO GRNs initially project along the antennal nerve, before branching ventrally to target the SOG. Both the neuron loss and the dendritic malformation phenotypes also are observed in other dll mutant genotypes, including dllSA1/dll+ and dll7 homozygotes (e.g., Fig. S4 A and B).

Fig. 3.

Dendrite malformations, axon projection defects, and support cell loss in dll-null embryos. Lateral views of stage 16 wild-type (A and A') and dll-null (B) embryos stained for Cut (blue), Dll (red), and sensory neurons (monoclonal antibody 22C10; green). Cut is coexpressed with Dll in the majority of DOG support cells (white arrowheads), TOG support cells (open arrowheads), and VOG support cells and is weakly coexpressed in a few neurons in all three ganglia. In dll-null embryos, the number of support cells is decreased and the remaining support cells are disorganized (compare B with A and A'). Lateral views of stage 16 wild-type (C and C′) and dll-null (D) embryonic heads stained for neurons (monoclonal antibody 22C10; green) and Dll (red). Dendrites (white arrows) of the DOG (white arrowheads) are malformed in dll-null embryos. Dendrites (open arrows) of the TOG (open arrowheads) are also abnormal. The axons from both olfactory and GRNs of the DOG initially project via the antennal nerve (white tracing in C). However, before reaching the brain, ORN and GRN axons normally defasciculate, with ORNs innervating the LAL and GRNs projecting to the SOG. Axons from the TOG and the VOG form the maxillary nerve (blue tracing in C), which also normally targets the SOG. In dll-null animals, afferent projections from the DOG and TOG form a single fascicle directed toward the SOG (asterisks in B and D). Absence of Dll staining was used to identify dll-null embryos in B and D. (A–B) Three-dimensional reconstructions of optical sections (0.4 μm) were collected with a 40× objective and a 1.4× digital zoom. (C–D) Optical sections (0.4 μm) were collected with a 40× objective. Anterior is to the left in all images. (Scale bars: 50 mm.)

dll Expression Persists in ato1 and amos1 Mutants.

ato and amos are necessary for the specification of DO ORNs, whereas members of the achaete–scute (AS–C) complex are needed for DO GRN specification (13). ato1, amos1, and sc19 mutant embryos have decreased numbers of DO neurons (ato1: ∼23 neurons; amos1: ∼27 neurons; and sc19: ∼29 neurons) (13). dll and ato are coexpressed in clusters of cells in the antennal and maxillary segments (Fig. S1 A and A′′); however, the loss-of-neuron phenotype observed in dll-null embryos is more severe with only seven DO neurons remaining, suggesting that dll functions either upstream of or in parallel to these proneural genes. Consistent with this idea, dll expression is not lost in ato1 or amos1 mutants, and dll continues to be expressed in the remaining DO, TO, and ventral organ (VO) neurons and support cells as well as in ectodermal cells associated with the sense organs (Fig. S3 E and F).

dll Is Necessary for the Development of Central Components of the Larval Olfactory System.

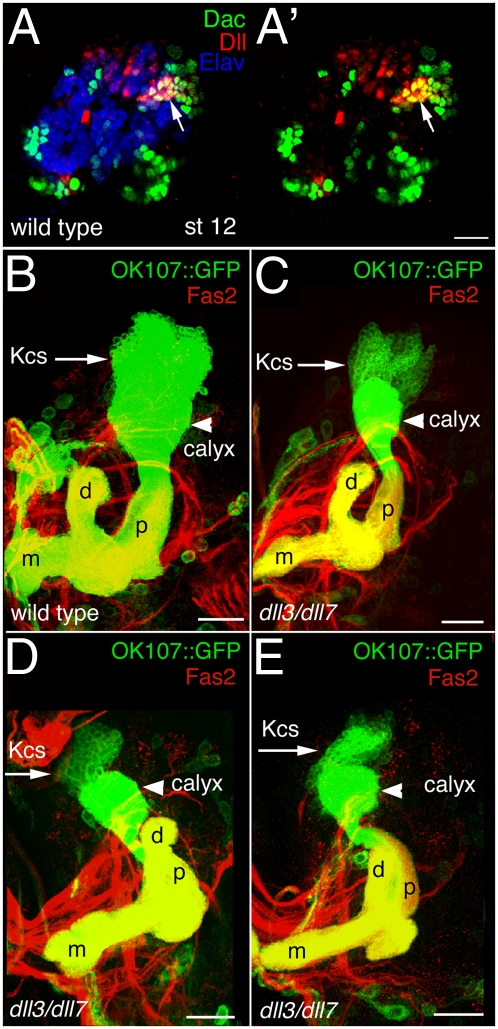

Based on lacZ enhancer trap analysis, Sprecher et al. (29) reported dll expression in a number of primary neural clusters in the protocerebrum and the anterior deutocerebrum, including all four of the late embryonic primary neuronal clusters that contribute to embryonic and larval MB tracts. Axons from these clusters create connections both within and between the protocerebral and deutocerebral neuromeres as well as provide a scaffold for fasciculation of axonal projections from late embryonic- and larval-born neurons (29–31). Here, we show Dll protein expression in the nascent MB Kenyon cells of stage 12 embryos (Fig. 4 A and A′) that persists into later embryonic stages 15 and 16 (Fig. S3 A and C). Consistent with this expression pattern, loss of dll activity leads to loss of a primary axon bundle emanating from the MBs and projecting along the dorsal and ventral tracts of the supraesophageal commissure (Fig. S3 A–D′). Reducing dll activity via either RNAi or mutation also leads to disruption of the MB peduncles (Fig. 4 B–E), indicating that dll is required for axon pathfinding and/or viability in the MB Kenyon cells. In dll3/dll7 hypomorphs, the Kenyon cell clusters are reduced in size by at least 50%, the calyces are markedly smaller, the dorsal and medial lobes are thinned, and the relative positions of the peduncle and the dorsal lobe are abnormal. Even stronger phenotypes were observed with elav-GAL4 driving a dll-RNAi construct. In this case, Fasciclin II (Fas2) was undetectable in the MBs. However, when a UAS-mCD8-GFP transgene was included to permit visualization of the Kenyon cells, the phenotype became much milder, probably because of titration of the GAL4 protein by UAS-mCD8-GFP. Similar titration effects have been reported previously (e.g., ref. 32). When UAS-dicer was added to enhance the dll-RNAi activity (genotype was w;UAS-dll-RNAi UAS-mCD8-GFP/+;UAS-dicer/+;OK107-GAL4/+), the phenotype was stronger, nearly identical to that observed for the dll3/dll7 hypomorphs, but still not as strong as dll-RNAi in the absence of other UAS-containing transgenes. Parallel experiments carried out with OK107-GAL4 yielded phenotypes similar to those observed with elav-GAL4, suggesting that the phenotypes seen in the dll mutants are intrinsic to the MB.

Fig. 4.

Loss of dll function disrupts the MBs. (A and A′) Lateral view of an embryonic stage 12 brain stained for Dac (green), Dll (red), and Elav (blue). Arrows point to young Kenyon cells, a subset of which coexpress Dll and Dac. (B–E) Frontal views of late third-instar MBs of wild-type (B) and dll3/dll7 (C–E) larvae carrying OK107-GAL4 driving UAS-mCD8-GFP (green) and stained with Fas2 antibody (red). The midline is toward the left. Arrows indicate the Kenyon cell clusters (Kcs), which are greatly reduced in the dll mutants. Arrowheads indicate the calyces, which also are reduced in the dll mutants. d, dorsal lobe; m, medial lobe; p, peduncle. The lobes and peduncles are thinner in the dll mutants, and the relative position of the peduncle and dorsal lobe is abnormal in the dll mutants. (Scale bars: 50 mm.)

However, we do observe additional brain defects in dll mutants. Specifically, in dll-null embryos, the brain commissures are defective (Fig. S3 A–D′) and the microtubule-associated Futsch protein recognized by monoclonal antibody 22C10 is consistently mislocalized (compare Fig. 3 D and C′ and Fig. S3 B and B′ with Fig. S3 A and A′). The supraesophageal commissure normally consists of three primary axon tracts (31). One of these is absent in the dll-null embryos (compare Fig. S3 C′ and D′), most likely the one emanating from the MBs. The subesophageal commissure consists of fascicles from at least two primary axon tracts (ref. 31, but see also ref. 33). Both of these are missing in dll-null embryos (Fig. S3 C–D′). These axon scaffold phenotypes are likely to reflect the effects of disrupting the development of multiple dll-expressing primary neural clusters.

Discussion

dll in DO Specification and Differentiation.

The DO phenotype exhibited by dll-null embryos is more severe than that of sc, amos, or ato single mutants or amos;ato double mutants, most closely resembling that of the sc;amos;ato triple mutants (13), indicating that dll might lie upstream of the proneural genes and regulate their expression in DO precursors. However, ato is expressed in the antennal segments of dll-null embryos, and dll is expressed in ato1 and amos1 mutants. Altogether, these data indicate that dll is likely to act in parallel with the proneural genes during DO development.

prospero (pros) also is required for DO development. pros encodes a homeodomain transcription factor that is asymmetrically distributed during SOP division (reviewed in ref. 34). In other contexts, pros represses neuronal stem-cell proliferation while promoting neuronal differentiation (35). Mutations in pros result in gustatory behavioral deficits (36) and disrupt axon and dendrite outgrowth from both DO and TO neurons (37). The axon pathfinding defects exhibited by pros mutants resemble those seen in dll-null embryos, although it is unclear whether the same subsets of neurons are affected.

dll in the Brain.

The axon scaffolding associated with the MBs in the embryonic brain is disrupted in dll-null embryos. Specifically, projections from the MB Kenyon cells across the supraesophageal commissure appear to be missing in late-stage embryos. MB defects also were observed in the brains of larvae in which postmitotic drivers such as elav-GAL4 and OR83b-GAL4 were used in conjunction with dll-RNAi to knock down activity. This finding indicates that dll also may be necessary for the later specification and/or differentiation of larval-born Kenyon cells. Because elav-GAL4 is not active until neurons are specified, the disruptions in the larval MBs observed in elav-GAL4;UAS-dll-RNAi animals are consistent with a role for dll in either axon guidance or viability of the postmitotic neurons.

The brain phenotypes we have detected in dll mutants resemble those of cephalic gap gene mutants. Specifically, loss of otd, ems, or btd results in embryonic brain segmentation defects and disrupts the formation of brain commissures and axon tracts (38, 39). In otd mutants, protocerebral neuroblasts, including the MB precursors, are missing. In ems and/or btd mutants, subsets of neuroblasts are lacking in the deutocerebral neuromere, which harbors the LAL, and the tritocerebral neuromere, which receives gustatory inputs. (40). It therefore is possible that dll is a key effector of cephalic gap gene function during brain development.

dll and Axons.

As described above, pros mutants exhibit DO axon defects similar to those of dll. It therefore is possible that Dll and Pros collaborate to regulate other genes needed for axon pathfinding by DOG neurons. In the brain, but not in the DOG or TO ganglion (TOG), we have observed mislocalization of Futsch protein in dll mutants. Futsch is a microtubule-associated protein with functions in both axonogenesis and dendritogenesis (41). It therefore is possible that some of the defects we observed in dll mutant MB lobes (which consist of axon tracts) and calyces (which contain Kenyon cell dendrites) are caused by misregulation of futsch. Other likely effectors of dll function during axon pathfinding in both DO and MB are Pak3 (42) and Down syndrome cell adhesion molecule (Dscam) (43–45). Both play important roles in axon guidance, including the targeting of adult Drosophila ORNs (42, 43). Both also have been identified as putative downstream targets of vertebrate Dlx1/2 (46). The loss-of-function Drosophila dll phenotypes in both DOG and MB are reminiscent of DSCAM phenotypes and consistent with dll regulation of DSCAM in multiple neuronal subtypes.

Given the dramatic reduction in Kenyon cell number in the dll hypomorphs, we might have expected the peduncles and lobes to be even thinner than observed. However, Noveen et al. (21) observed a similar reduction in Kenyon cell number without concomitant thinning of the lobes in eyR mutants. In this case, ablation studies were used to demonstrate that, at late third instar, recently born Kenyon cells have not yet contributed to MB lobes. We therefore anticipate that MB defects may be more pronounced in dll mutant adults.

Drosophila dll and Vertebrate Dlx Function.

This work constitutes an important description of dll function in the invertebrate nervous system. We have demonstrated requirements for dll in multiple neuronal subtypes, including the larval Drosophila ORNs, GRNs, and Kenyon cells. Vertebrate Dlx genes are required for the specification, differentiation, and migration of neural progenitor cells that both build and regenerate parts of the olfactory system (reviewed in ref. 1). The reagents and techniques available in Drosophila, together with the existence of a single dll gene, make it a powerful model for investigation of dll function and have the potential to provide insight into how disruptions in Dlx function result in aberrant neural development in vertebrates and contribute to neuropathologies such as epilepsy, Rett syndrome, and autism as well as to the neurological defects associated with Down syndrome (47–51).

The functions of the cephalic gap genes in Drosophila and vertebrate brains are proposed to represent conserved genetic programs in the development of the central nervous systems of insects and mammals (52–54). Nonetheless, because of differences in ORN specification and targeting, it is not thought that the olfactory systems of vertebrates and invertebrates share a common origin (e.g., refs. 3 and 55). However, the growing number of developmental genetic parallels, including the requirements for dll and the Dlx genes part of the invertebrate and vertebrate olfactory systems, in conjunction with the similar wiring of these systems, suggests that this question should be revisited. Even if the vertebrate and invertebrate olfactory systems have evolved independently toward similar architectures, there is now sufficient precedent from other tissue and organ systems that the genetic tool kit is likely to be conserved and that further studies in Drosophila will provide insights into the mechanisms regulating the differentiation of olfactory system components (56).

Materials and Methods

Embryo collection and fixation were performed as described (57) with staging of embryos according to Campos-Ortega and Hartenstein (58). For Xgal stainings, third instar larvae were dissected in PBS and larval heads were fixed and stained according to (59). Confocal images were collected on a Zeiss LSM 510 microscope. 3D reconstructions were made using Zeiss LSM software and images were processed using combinations of Zeiss LSM filtering functions, Image J and Adobe Photoshop. For scanning electron micrographs, third instar samples were fixed overnight at 4 °C according to Gerber et al. (60). Following a graded EtOH series, samples were covered in gold palladium using an Auto Conductavac IV Sputter Coater, and a Hitachi S570 scanning electron microscope with a Gatan digital capture system was used to collect the images. Larval behavioral assays were performed according to Rodrigues and Siddiqi (61). For a detailed description of materials and methods including Drosophila strains, immunohistochemistry procedures, confocal and scanning electron microscopy, and behavioral assays, see SI Materials and Methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Ralph Albrecht and Joseph Heinz for scanning electron microscopy training and access; Hugo Bellen for sens and ato antibodies; Dan Eberl for ato1/ato1 flies; Andrew Jarman and Petra zur Lage for ato and amos antibodies and mutants; and Janie Yang for technical assistance. We also thank Drs. Margaret McFall-Ngai and Ned Ruby for access to the Zeiss LSM confocal microscope in the University of Wisconsin Department of Medical Microbiology and Immunology (which is supported by National Institutes of Health Grant RR12294). The monoclonal, Cut Elav, Fas2, Pros, Repo, and 22C10 antibodies used in these studies were obtained from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, developed under the auspices of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, and maintained by the University of Iowa Department of Biological Sciences. We thank the Transgenic RNAi Project (TRiP) at Harvard Medical School (National Institutes of Health/National Institute of General Medical Sciences Grant R01-GM084947) for providing transgenic RNAi fly stocks and/or plasmid vectors used in this study. The authors are grateful for the thoughtful comments of two anonymous reviewers. J.P. was supported by National Institutes of Health Training Grant T32 GM-7507 and a grant from the University of Wisconsin Graduate School. This work also was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant R01 GM59871 (to G.B.-F.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

*This Direct Submission article had a prearranged editor.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1016741109/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Panganiban G, Rubenstein JL. Developmental functions of the Distal-less/Dlx homeobox genes. Development. 2002;129:4371–4386. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.19.4371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Panganiban G, et al. The origin and evolution of animal appendages. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:5162–5166. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.10.5162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vosshall LB, Stocker RF. Molecular architecture of smell and taste in Drosophila. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2007;30:505–533. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.30.051606.094306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gerber B, Stocker RF. The Drosophila larva as a model for studying chemosensation and chemosensory learning: A review. Chem Senses. 2007;32(1):65–89. doi: 10.1093/chemse/bjl030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Singh R, Singh K. Fine structure of the sensory organs of Drosophila melanogaster Meigen larva (Diptera: Drosophilidae) Int J Insect Morphol Embryol. 1984;13(4):255–273. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tissot M, Gendre N, Hawken A, Störtkuhl KF, Stocker RF. Larval chemosensory projections and invasion of adult afferents in the antennal lobe of Drosophila. J Neurobiol. 1997;32(3):281–297. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4695(199703)32:3<281::aid-neu3>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davis RL. Olfactory memory formation in Drosophila: From molecular to systems neuroscience. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2005;28:275–302. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.28.061604.135651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heisenberg M. Mushroom body memoir: From maps to models. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2003;4(4):266–275. doi: 10.1038/nrn1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Joiner WJ, Crocker A, White BH, Sehgal A. Sleep in Drosophila is regulated by adult mushroom bodies. Nature. 2006;441:757–760. doi: 10.1038/nature04811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martin JR, Ernst R, Heisenberg M. Mushroom bodies suppress locomotor activity in Drosophila melanogaster. Learn Mem. 1998;5(1-2):179–191. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pitman JL, McGill JJ, Keegan KP, Allada R. A dynamic role for the mushroom bodies in promoting sleep in Drosophila. Nature. 2006;441:753–756. doi: 10.1038/nature04739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sakai T, Kitamoto T. Differential roles of two major brain structures, mushroom bodies and central complex, for Drosophila male courtship behavior. J Neurobiol. 2006;66:821–834. doi: 10.1002/neu.20262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grillenzoni N, et al. Role of proneural genes in the formation of the larval olfactory organ of Drosophila. Dev Genes Evol. 2007;217(3):209–219. doi: 10.1007/s00427-007-0135-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schmidt-Ott U, González-Gaitán M, Jäckle H, Technau GM. Number, identity, and sequence of the Drosophila head segments as revealed by neural elements and their deletion patterns in mutants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:8363–8367. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.18.8363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cohen SM, Jürgens G. Mediation of Drosophila head development by gap-like segmentation genes. Nature. 1990;346:482–485. doi: 10.1038/346482a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cohen SM, Jürgens G. Proximal-distal pattern formation in Drosophila: Cell autonomous requirement for Distal-less gene activity in limb development. EMBO J. 1989;8:2045–2055. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb03613.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Technau G, Heisenberg M. Neural reorganization during metamorphosis of the corpora pedunculata in Drosophila melanogaster. Nature. 1982;295:405–407. doi: 10.1038/295405a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ito K, Hotta Y. Proliferation pattern of postembryonic neuroblasts in the brain of Drosophila melanogaster. Dev Biol. 1992;149(1):134–148. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(92)90270-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fahrbach SE. Structure of the mushroom bodies of the insect brain. Annu Rev Entomol. 2006;51:209–232. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ento.51.110104.150954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kurusu M, et al. A conserved nuclear receptor, Tailless, is required for efficient proliferation and prolonged maintenance of mushroom body progenitors in the Drosophila brain. Dev Biol. 2009;326(1):224–236. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Noveen A, Daniel A, Hartenstein V. Early development of the Drosophila mushroom body: The roles of eyeless and dachshund. Development. 2000;127:3475–3488. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.16.3475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Callaerts P, et al. Drosophila Pax-6/eyeless is essential for normal adult brain structure and function. J Neurobiol. 2001;46(2):73–88. doi: 10.1002/1097-4695(20010205)46:2<73::aid-neu10>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kurusu M, et al. Genetic control of development of the mushroom bodies, the associative learning centers in the Drosophila brain, by the eyeless, twin of eyeless, and dachshund genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:2140–2144. doi: 10.1073/pnas.040564497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martini SR, Roman G, Meuser S, Mardon G, Davis RL. The retinal determination gene, dachshund, is required for mushroom body cell differentiation. Development. 2000;127:2663–2672. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.12.2663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kurusu M, et al. Embryonic and larval development of the Drosophila mushroom bodies: Concentric layer subdivisions and the role of fasciclin II. Development. 2002;129:409–419. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.2.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Python F, Stocker RF. Adult-like complexity of the larval antennal lobe of D. melanogaster despite markedly low numbers of odorant receptor neurons. J Comp Neurol. 2002;445:374–387. doi: 10.1002/cne.10188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lilly M, Carlson J. smellblind: A gene required for Drosophila olfaction. Genetics. 1990;124(2):293–302. doi: 10.1093/genetics/124.2.293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lilly M, Kreber R, Ganetzky B, Carlson JR. Evidence that the Drosophila olfactory mutant smellblind defines a novel class of sodium channel mutation. Genetics. 1994;136:1087–1096. doi: 10.1093/genetics/136.3.1087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sprecher SG, Reichert H, Hartenstein V. Gene expression patterns in primary neuronal clusters of the Drosophila embryonic brain. Gene Expr Patterns. 2007;7:584–595. doi: 10.1016/j.modgep.2007.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Younossi-Hartenstein A, Nguyen B, Shy D, Hartenstein V. Embryonic origin of the Drosophila brain neuropile. J Comp Neurol. 2006;497:981–998. doi: 10.1002/cne.20884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nassif C, Noveen A, Hartenstein V. Embryonic development of the Drosophila brain. I. Pattern of pioneer tracts. J Comp Neurol. 1998;402(1):10–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grillenzoni N, Flandre A, Lasbleiz C, Dura JM. Respective roles of the DRL receptor and its ligand WNT5 in Drosophila mushroom body development. Development. 2007;134:3089–3097. doi: 10.1242/dev.02876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Therianos S, Leuzinger S, Hirth F, Goodman CS, Reichert H. Embryonic development of the Drosophila brain: Formation of commissural and descending pathways. Development. 1995;121:3849–3860. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.11.3849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fuerstenberg S, Broadus J, Doe CQ. Asymmetry and cell fate in the Drosophila embryonic CNS. Int J Dev Biol. 1998;42:379–383. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Choksi SPST, et al. Prospero acts as a binary switch between self-renewal and differentiation in Drosophila neural stem cells. Dev Cell. 2006;11:775–789. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grosjean Y, Lacaille F, Acebes A, Clemencet J, Ferveur JF. Taste, movement, and death: Varying effects of new prospero mutants during Drosophila development. J Neurobiol. 2003;55(1):1–13. doi: 10.1002/neu.10208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Guenin L, et al. Spatio-temporal expression of Prospero is finely tuned to allow the correct development and function of the nervous system in Drosophila melanogaster. Dev Biol. 2007;304(1):62–74. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Younossi-Hartenstein A, et al. Control of early neurogenesis of the Drosophila brain by the head gap genes tll, otd, ems, and btd. Dev Biol. 1997;182(2):270–283. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.8475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hirth F, et al. Developmental defects in brain segmentation caused by mutations of the homeobox genes orthodenticle and empty spiracles in Drosophila. Neuron. 1995;15:769–778. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90169-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rajashekhar KP, Singh RN. Neuroarchitecture of the tritocerebrum of Drosophila melanogaster. J Comp Neurol. 1994;349:633–645. doi: 10.1002/cne.903490410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hummel T, Krukkert K, Roos J, Davis G, Klämbt C. Drosophila Futsch/22C10 is a MAP1B-like protein required for dendritic and axonal development. Neuron. 2000;26:357–370. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81169-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ang LH, Kim J, Stepensky V, Hing H. Dock and Pak regulate olfactory axon pathfinding in Drosophila. Development. 2003;130:1307–1316. doi: 10.1242/dev.00356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hummel T, et al. Axonal targeting of olfactory receptor neurons in Drosophila is controlled by Dscam. Neuron. 2003;37(2):221–231. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)01183-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schmucker D, et al. Drosophila Dscam is an axon guidance receptor exhibiting extraordinary molecular diversity. Cell. 2000;101:671–684. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80878-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang J, Zugates CT, Liang IH, Lee CH, Lee T. Drosophila Dscam is required for divergent segregation of sister branches and suppresses ectopic bifurcation of axons. Neuron. 2002;33:559–571. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00570-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cobos I, Borello U, Rubenstein JL. Dlx transcription factors promote migration through repression of axon and dendrite growth. Neuron. 2007;54:873–888. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cobos I, et al. Mice lacking Dlx1 show subtype-specific loss of interneurons, reduced inhibition and epilepsy. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:1059–1068. doi: 10.1038/nn1499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hamilton SP, et al. Analysis of four DLX homeobox genes in autistic probands. BMC Genet. 2005;6:52. doi: 10.1186/1471-2156-6-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Horike S, Cai S, Miyano M, Cheng JF, Kohwi-Shigematsu T. Loss of silent-chromatin looping and impaired imprinting of DLX5 in Rett syndrome. Nat Genet. 2005;37(1):31–40. doi: 10.1038/ng1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liu X, et al. The DLX1 and DLX2 genes and susceptibility to autism spectrum disorders. Eur J Hum Genet. 2009;17(2):228–235. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2008.148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lockstone HE, et al. Gene expression profiling in the adult Down syndrome brain. Genomics. 2007;90:647–660. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2007.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Arendt D, Nübler-Jung K. Comparison of early nerve cord development in insects and vertebrates. Development. 1999;126:2309–2325. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.11.2309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Reichert H, Simeone A. Conserved usage of gap and homeotic genes in patterning the CNS. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1999;9:589–595. doi: 10.1016/S0959-4388(99)00002-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sprecher SG, Reichert H. The urbilaterian brain: Developmental insights into the evolutionary origin of the brain in insects and vertebrates. Arthropod Struct Dev. 2003;32(1):141–156. doi: 10.1016/S1467-8039(03)00007-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bargmann CI. Comparative chemosensation from receptors to ecology. Nature. 2006;444(7117):295–301. doi: 10.1038/nature05402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Carroll SB. Endless Forms Most Beautiful: The New Science of Evo Devo and the Making of the Animal Kingdom. New York: Norton; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Langeland JA. Imaging immunolabeled Drosophila embryos by confocal microscopy. In: Paddock S, editor. Confocal Microscopy Methods and Protocols, Methods in Molecular Biology. Vol 122. Totowa, NJ: Humana; 1999. pp. 167–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Campos-Ortega J, Hartenstein V. The Embryonic Development of Drosophila melanogaster. Berlin: Springer; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hazelrigg T. GFP and other reporters. In: Sullivan W, Ashburner M, Hawley RS, editors. Drosophila Protocols. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Lab Press; 2000. pp. 313–344. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gerber B, et al. Visual learning in individually assayed Drosophila larvae. J Exp Biol. 2004;207:179–188. doi: 10.1242/jeb.00718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rodrigues V, Siddiqi O. Genetic analysis of chemosensory pathway. Proc Ind Acad Sci. 1978;87B:147–160. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.