Abstract

Two canonical subunits of the 26S proteasome, Rpn10 and Rpn13, function as ubiquitin (Ub) receptors. The mutual arrangement of these subunits—and all other non-ATPase subunits—in the regulatory particle is unknown. Using electron cryomicroscopy, we calculated difference maps between wild-type 26S proteasome from Saccharomyces cerevisiae and deletion mutants (rpn10Δ, rpn13Δ, and rpn10Δrpn13Δ). These maps allowed us to localize the two Ub receptors unambiguously. Rpn10 and Rpn13 mapped to the apical part of the 26S proteasome, above the N-terminal coiled coils of the AAA-ATPase heterodimers Rpt4/Rpt5 and Rpt1/Rpt2, respectively. On the basis of the mutual positions of Rpn10 and Rpn13, we propose a model for polyubiquitin binding to the 26S proteasome.

Keywords: EM single-particle analysis, protein degradation, ubiquitin-proteasome pathway, subunit localization, quantitative mass spectrometry

In eukaryotes, targeted protein degradation by the ubiquitin-proteasome system is required for cellular proteostasis (1). Proteins destined for degradation by the 26S proteasome are modified by covalent attachment of polyubiquitin chains. Chains of at least four ubiquitins are required for efficient recognition by the 26S proteasome (2, 3), but also the type of lysine linkage has an influence on degradation efficiency (for reviews see refs. 4 and 5).

The 26S proteasome is composed of 33 different canonical subunits and comprises two subcomplexes: the cylindrical 20S core particle (CP) harboring the proteolytic chamber and one or two 19S subcomplexes, often referred to as regulatory particles (RPs) (6–8). The RP fulfills several functions, such as substrate recognition, deubiquitylation, unfolding, opening the gate of the CP, and translocation of substrates into the CP. The RP is built of 19 different subunits, but their three-dimensional organization remains unknown.

Two subunits of the RP, Rpn10/S5a and Rpn13, are the major ubiquitin (Ub) receptors of the 26S proteasome (2, 9–11). Rpn10 is composed of an N-terminal von Willebrand factor A (VWA) domain and C-terminal ubiquitin-interacting motifs (UIMs) that bind to ubiquitin (12, 13). Saccharomyces cerevisiae Rpn10 contains only one UIM, whereas human and Drosophila S5a contain two and three UIMs, respectively (Fig. S1). The affinity of the UIMs for Ub chain increases with its length (2, 3). Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy studies have shown that the UIMs consist of helices without a defined tertiary structure that adopt a more ordered conformation upon ubiquitin binding (13). Mutations of the VWA domain of Rpn10 promote dissociation of the RP into two modules referred to as the base and lid (14, 15). The base is thought to be proximal to the CP and the lid distal. It has been proposed that Rpn10 acts as a hinge connecting these two modules (14, 15). In most species, Rpn13 is composed of an N-terminal pleckstrin-like receptor of ubiquitin (PRU) domain, which binds ubiquitin with high affinity (10, 11) and a C-terminal extension consisting of a nine-helix bundle that binds to the deubiquitylating enzyme Uch37/UchL5 (16–18) (Fig. S1). In S. cerevisiae, Rpn13 lacks the C-terminal extension and there is no Uch37 ortholog. Rpn13 binds to the C-terminal domain of Rpn2 through its PRU domain (10, 11, 16).

Deletions of the Ub receptors Rpn10 and Rpn13 are viable in yeast (9–11), probably because of the redundancy of proteasomal Ub receptors (8). In addition to Rpn10 and Rpn13, Rpt5 was reported to be cross-linked with Ub chains (19). Furthermore, shuttling Ub receptors, such as Rad23, Dsk2, and Ddi1, bind the 26S proteasome transiently (20–23). These proteins share an ubiquitin-like domain that binds to the 26S proteasome and an ubiquitin-associated domain capable of binding polyubiquitylated substrates (20, 23). In yeast, Dsk2 is reported to bind to Rpn10, Rpn1, and Rpn13 with similar affinity (20, 24, 25); it binds to Rpn10 preferentially in Drosophila melanogaster (26).

Recently, we reported the cryoelectron microscopy (cryo-EM) structures of the D. melanogaster 26S proteasome at 21-Å resolution (27) and Schizosaccharomyces pombe at 9.1-Å resolution (28). The S. pombe structure and the X-ray crystallographic structures of the proteasome-associated nucleotidase (PAN) (29, 30) allowed us to map the AAA-ATPases Rpt1–6 (28). Numerous pairwise interactions among other RP subunits have been identified by cross-linking, biochemical, and genetic studies, providing information on the spatial proximity of subunits (31). However, for most RP subunits, including the Ub receptors, structural data are too scarce for a precise localization, preventing the completion of a comprehensive structural and functional model of the RP.

In this work, we purified 26S proteasomes from S. cerevisiae mutant strains lacking one or both Ub receptors (rpn10Δ, rpn13Δ, and rpn10Δrpn13Δ) and studied them by cryo-EM single-particle analysis. By comparing the densities of the wild-type and the deletion mutant structures, we are able to map the two Ub receptors Rpn10 and Rpn13 in the 26S proteasome. Furthermore, we mapped the Rpn10 UIMs by using cryo-EM maps of D. melanogaster proteasomes with Dsk2 bound. Interestingly, both Ub receptors were localized in the apical part of the RP, in contrast to current hypotheses. These locations are well positioned for tight binding and further processing of substrates by the AAA-ATPases following the initial recruitment of substrates.

Results

26S Proteasome Assembly in Ub Receptor Deletion Mutants.

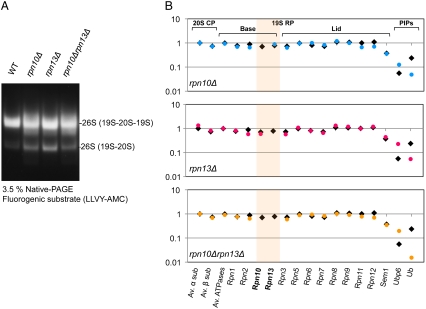

For cryo-EM, 26S proteasomes were isolated via a FLAG tag on Rpn11 from strains lacking the genes for Ub receptors: rpn10Δ, rpn13Δ, and double deletions rpn10Δrpn13Δ (32, 33) (Table S1). After affinity purification, samples were fractionated by sucrose gradient ultracentrifugation, and the fraction containing the highest concentration of 26S proteasome was subjected to native PAGE and quantitative mass spectrometry (MS). Native PAGE showed that wild type and all mutants contained double- and single-capped 26S proteasomes (Fig. 1A). According to our MS results, all canonical 26S proteasome subunits (α1–7, β1–7, Rpt1–6, Rpn1–3, and Rpn5–13) were present in stoichiometric amounts in wild-type S. cerevisiae 26S proteasome (Fig. 1B). In contrast to S. cerevisiae, Rpn13 was found to be present in substoichiometric amounts in D. melanogaster and S. pombe 26S proteasomes, whereas Rpn10 has a higher occupancy in S. cerevisiae and S. pombe than in the D. melanogaster (27, 28). The abundance of the Sem1 subunit could not be determined accurately because of its small size (33).

Fig. 1.

(A) Affinity purified 26S proteasome, followed by sucrose gradient centrifugation, from wild-type, rpn10Δ, rpn13Δ, and rpn10Δrpn13Δ cells were resolved with 3.5% native PAGE and detected by fluorogenic substrate (LLVY-AMC) activity. Most of the purified proteasomes were in the double-capped form. (B) Subunit composition and relative abundance of wild-type (black square) and mutated proteasome (colored circle) were analyzed by quantitative proteomics. Measured peptide intensities were summed and normalized according to the protein molecular mass (27). It confirms that Rpn10 and/or Rpn13 were knocked out in the corresponding deletion mutants and the stoichiometry of the remaining subunits was not altered by these deletions.

Quantitative MS confirmed that Rpn10 and/or Rpn13 were absent from the corresponding deletion mutants; but the stoichiometry of the remaining subunits was not altered by these deletions (Fig. 1B). However, ubiquitin binding to the 26S proteasome was reduced fourfold upon deletion of Ub receptors in rpn10Δ, rpn13Δ, and rpn10Δrpn13Δ. Ubp6, a deubiquitylating enzyme that regulates the gate-opening of the CP (34), showed slightly increased binding affinity in deletion mutants, probably compensating for the reduced substrate affinity to the proteasome. Moreover, 26S proteasomes in our preparation contained low amounts of proteasome interacting proteins (PIPs), as reported previously (33).

EM Map of 26S Proteasome from Wild-Type S. cerevisiae.

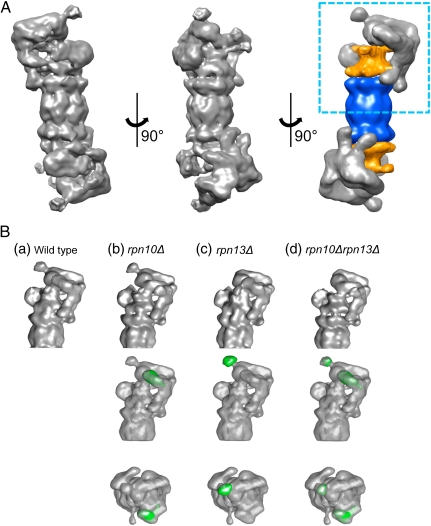

Electron micrographs of ice-embedded wild-type 26S proteasomes from S. cerevisiae were acquired, and a three-dimensional (3D) structure from 44,000 particles was computed as previously described (28) (Fig. S2). The resolution of the final reconstruction was estimated to be 16.8 Å by using the Fourier shell correlation (FSC) 0.5 cutoff criterion or 12.1 Å by using the criterion FSC = 0.3 (Fig. S3). The structure of the wild-type 26S proteasome from S. cerevisiae showed essentially the same features as observed for the 26S proteasome from other species (27, 28, 35) (Fig. 2A). The most prominent difference of the S. cerevisiae proteasomes compared to those from D. melanogaster and S. pombe was an additional bulbous protrusion at the apex of the RP (see also Fig. S5A). Taking into account that our proteomics results showed no significant PIPs binding to the proteasome, we concluded that this extra density should correspond to one of the canonical proteasomal subunits (Figs. 1B and 2A).

Fig. 2.

(A) Three-dimensional structure of the 26S proteasome from S. cerevisiae. Surface representation of three orientations of the cryo-EM map of 26S proteasome, and its segmentation (Right) into 20S CP (blue) and AAA-ATPase (orange). The resolution of wild-type structure is 16.8 Å according to the FSC = 0.5 criterion (12.1 Å for FSC = 0.3). (B) Structural comparisons and the difference maps of mutated proteasomes rpn10Δ, rpn13Δ, and rpn10Δrpn13Δ calculated for the wild-type structure. For representation of the maps (top row), we chose the area highlighted by the rectangle in A, Right. The middle and bottom rows display the difference maps (missing densities in green) superposed on the wild-type maps in side and top view, respectively.

Subunit Localizations of Ub Receptors in the 26S Proteasome.

To localize Ub receptors within the 26S proteasome, we determined the cryo-EM structures of proteasomes from rpn10Δ, rpn13Δ, and rpn10Δrpn13Δ deletion mutants and compared them to that of the 26S wild-type proteasome from S. cerevisiae. The datasets comprised 18,000, 19,000, and 12,000 particles for rpn10Δ, rpn13Δ, and rpn10Δrpn13Δ, respectively (Fig. S2). For a detailed analysis of the differences, the EM reconstructions of deletion mutants were superimposed onto the wild-type 26S proteasome structure (Fig. 2B, lower rows, and Fig. S4). The local losses of density observed in these difference maps indicated the positions of the corresponding subunits.

Compared to the wild-type 26S proteasome, essentially all structural features were preserved upon deletion of rpn10, rpn13, or both (Fig. 2B, upper row, and Fig. S4). By far the most pronounced difference density observed in rpn10Δ is positioned in the distal part of the RP above the coiled coils of the Rpt4/Rpt5 dimer (Fig. 2B, Middle and Lower rows). The difference density appears globular in shape and has an estimated mass of approximately 20 kDa, which is in good agreement with the molecular weight of the Rpn10 VWA domain (36). The C-terminal Rpn10 domain does not exhibit a defined tertiary structure (13), and therefore it is averaged out in the EM structure.

Furthermore, we found that the major density difference of rpn13Δ colocalized with the aforementioned bulbous protrusion observed so far only with the S. cerevisiae proteasomes (Fig. 2B and Fig. S5A). The density is of globular shape and resides approximately 70 Å above the coiled coils of the Rpt1/Rpt2 dimer. The estimated mass of the difference density is approximately 20 kDa, consistent with Rpn13’s size. In the case of the double deletion rpn10Δrpn13Δ, two distinct differences were observed in exactly the same positions as in the corresponding single mutants. In none of the three deletion mutants did we observe any other significant differences.

We further aimed to localize the flexible C-terminal UIM-containing domain of Rpn10, which was not well resolved in the difference map. As a label for the C-terminal Rpn10 domain we used Dsk2, which has an Ubl domain that binds to UIMs with higher affinity than ubiquitin. For this purpose, we used D. melanogaster 26S proteasomes whose Rpn10 subunit contains three UIMs and hence has higher affinity toward Dsk2 than S. cerevisiae Rpn10 (26) (Fig. S1). To enrich Dsk2 in the sample, we purified D. melanogaster proteasomes using Dsk2 as bait. Although the pull-down experiment enriched Dsk2 20-fold compared to conventionally purified 26S preparations (27), Dsk2 still showed a low occupancy (approximately 15%). No significant difference was observed in the total averaged 3D structure of proteasomes purified by using this method compared to the density obtained with conventionally purified 26S preparations. To distinguish structural variations due to Dsk2 binding to Rpn10 from structural variations elsewhere in the holocomplex, we further analyzed the two D. melanogaster and the S. cerevisiae maps by using classification focused on the area where we localized the Rpn10 VWA domain in S. cerevisiae, as described in ref. 28. We found a class average in the Dsk2-enriched sample with an additional density that was not present in the non-Dsk2-labeled 26S proteasomes in neither S. cerevisiae nor D. melanogaster (Fig. S6). This density was present in approximately 19% of the particles, in agreement with our proteomics data. The extra density was localized between the observed density difference in rpn10Δ and the coiled coil formed by the N-terminal domains of Rpt5 and Rpt4. Thus, we conclude that the C terminus of Rpn10, which binds ubiquitin, is oriented toward the coiled coils of Rpt5 and Rpt4.

Rpn13 Binds Substoichiometrically in D. melanogaster and S. pombe.

Our difference maps showed that the bulbous protrusion of the RP corresponds to Rpn13. A remarkable property of 26S proteasomes from S. cerevisiae is the presence of Rpn13 in stoichiometric amounts, whereas Rpn13 is present substoichiometrically in 26S proteasomes from D. melanogaster and S. pombe. To investigate whether at least a subpopulation of the particles isolated from D. melanogaster and S. pombe exhibit density at the Rpn13 site, we applied 3D classification focused on the Rpn13 site to 26S proteasome particles. For comparison, we applied the same procedure to S. cerevisiae particles. Approximately 20,000 particles of each 26S holocomplex were grouped into six classes (Fig. S5B). We found that approximately 50% of D. melanogaster and S. pombe proteasomes exhibited an extra density at the Rpn13 site, which is in good agreement with our quantitative proteomics data (27, 28). Rpn13 is likely not observed in the global averages of S. pombe and D. melanogaster because of the low abundance and structural flexibility of Rpn13.

In contrast, all classes from S. cerevisiae contained Rpn13, which is consistent with our proteomics data. Interestingly, in some classes we observed additional densities associated with Rpn13 (Fig. S5B). Because Rpn13 is not known to interact with any PIPs in S. cerevisiae (in contrast to S. pombe and D. melanogaster Rpn13, which interact with Uch2 and Uch37, respectively) and because our MS data indicate the abundance of ubiquitin, we hypothesize that these extra densities in the class averages may correspond to ubiquitin, possibly linked to substrates.

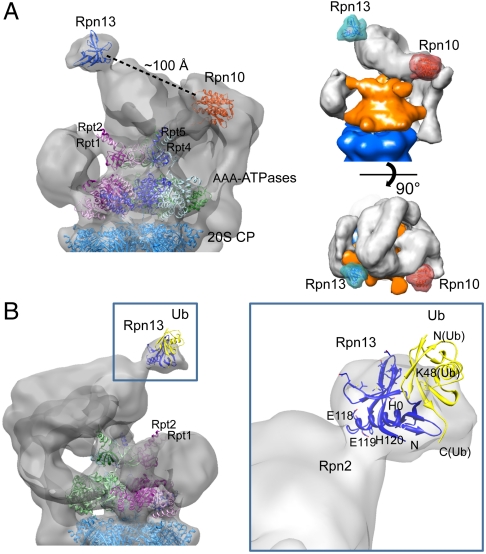

Fitting Crystal Structures into the Cryo-EM Map.

For further structural interpretation, we attempted to fit the crystal structures of Rpn10 and Rpn13 into the cryo-EM map of the wild-type 26S proteasome (10, 11, 36). When correlating the Rpn10 structure with the entire 26S proteasome, the maximum correlation did not coincide with the experimentally determined Rpn10 site, which is probably due to the small size of Rpn10, its structural variability, and the modest resolution of the EM map. In contrast, fitting of Rpn13 yielded a clear correlation maximum at the Rpn13 site, even though a higher resolution map may be needed to corroborate Rpn13 orientation (Fig. 3A). NMR studies suggested that the H0 helix, S1 and S7 sheets, and S5–S6 and S7–H0 loops of Rpn13 contact the N-terminal domain of Rpn2, whereas the loops between S2–S3, S4–S5, and S6–S7 are involved in ubiquitin binding (16). We found that the H0 helix of Rpn13, which is at the C terminus of the PRU domain, is located at the molecular interface with the RP, possibly its largest subunit, Rpn2. Taken together, we assume that the C-terminal domain of Rpn2 is located near the apex of the 26S proteasome. According to this model, the ubiquitin-binding surface of Rpn13 is exposed to solvent, with its normal projecting away from the Rpn10 VWA domain. The fit of Rpn13 suggests that the C terminus of ubiquitin is orientated toward the axial channel of the AAA-ATPases module (Fig. 3B). Substrates conjugated to the C-terminal glycine of the ubiquitin molecule would be orientated to the channel and, therefore, be well positioned for unfolding by the N-terminal domains of the AAA-ATPases and for translocation into the CP.

Fig. 3.

(A) Representation of 3D localization of Ub receptors and fits of the atomic models. Two views of the cryo-EM 26S proteasome after fitting the atomic models of Rpn10 [light red, Protein Data Bank (PDB) ID code 2X5N] and Rpn13 (light blue, PDB ID code 2R2Y) into the EM densities at the experimentally determined locations. Densities of the proteasome were rendered semitransparent to show the structures of Rpn10 and Rpn13 (ribbon representation). CP and AAA-ATPase are shown in ribbon representation. The distance between Rpn10 and Rpn13 is approximately 100 Å. (B) Localization of Rpn13 and Ub-binding model of 26S proteasome in close-up view. The H0 helix of Rpn13, which is at the C terminus of the PRU domain, is located at the molecular interface with the RP, possibly its largest subunit, Rpn2. Ubiquitin was docked into the proteasome map on the basis of Rpn13-ubiquitin structures determined by NMR spectroscopy (PDB ID code 2Z59). The C terminus of ubiquitin is orientated toward the coiled coils of the AAA-ATPases Rpt1/Rpt2.

Discussion

Localization of the Ub Receptors.

The 26S proteasome subunits should be positioned such that they can support the sequence of events in the preparation of substrates for degradation. In spite of a wealth of biological and genetic data and a recent cryo-EM structure of the S. pombe 26S proteasome at 9.1-Å resolution (28), the mutual arrangement of the RP subunits is largely unknown. Here, we determined the positions of the known proteasomal Ub receptors Rpn10 and Rpn13. We found that the N-terminal VWA domain of Rpn10 is located at the apical part of the RP. Most of the VWA domain protein surface is buried in contacts with RP proteins, which is consistent with the numerous physical interactions for Rpn10: It was reported to interact with Rpn1, Rpn2, Rpn9, and Rpn12 (23, 36–39). In contrast, Rpn13 forms a bulbous, largely solvent-exposed protrusion on the apical surface of the RP. This finding is in agreement with physical interaction data showing that Rpn13 interacts only with Rpn2 (10, 11, 16, 31). Interestingly, both Ub receptors are positioned in the apical part of the RP near the periphery. These positions explain in part why the respective knockouts are not lethal; Rpn10 and Rpn13 are obviously not essential for maintaining the structural integrity of the RP.

Implications of Ub Receptor Positions on Structure of the “Base” Subcomplex.

So far, it had been assumed that Rpn1, Rpn2, and six AAA-ATPases together with the Ub receptors Rpn10 and Rpn13 serve as a basal scaffold of the RP near the interface to the CP (the so-called base), whereas non-ATPase subunits were believed to form the lid covering the central pore of the ATPase ring (14). In this study, we localized the Ub receptors Rpn10 and Rpn13 in the apical part of the RP rather than in proximity to the α-ring of the CP.

On the basis of circumstantial evidence showing a substoichiometric binding of Rpn10 in D. melanogaster, we had previously proposed that a variable density observed adjacent to Rpt1 and Rpt2 contains Rpn10 (27). Contrary to that hypothesis, the variable density was present not only in wild-type S. cerevisiae proteasomes but also in the rpn10Δ mutant (Fig. 2 A and B). Furthermore, our modeling data on the basis of pairwise interactions among proteasome subunits suggest that Rpn1 is hosted within the variable density (31). Thus, the variable density likely hosts Rpn1 rather than Rpn10. The observed variability of the density probably arises from structural flexibility of the largely solenoid-like Rpn1, which may be key for its function as a substrate recruitment factor.

Rpn2, which has been shown to bind both the AAA-ATPases Rpt4 and Rpt5 (33), as well as Rpn13 (16), must extend to the distal parts of the RP. Thus, Rpn2 seems to span the RP from its proximal to its distal part, probably forming a scaffold for the lid. Contrary to prevalent models, the base subcomplex does not form a largely globular entity proximal to the CP.

Recently, we reported the crystal structure of Rpn6 and revealed its localization in the cryo-EM map of the 26S proteasome (40). We also found that the proteasome-COP9-initiation factor 3 domain, which is conserved among non-ATPase subunits, mediates interactions between the lid subunits. The lid subcomplex forms a horseshoe structure in the RP. This structural model of the lid and its position in the RP are consistent with the spatial arrangement of the base, as it emerges from this study.

Ub Receptors May Jointly Function to Recognize Polyubiquitin Length.

Here, we showed that both canonical Ub receptors are located at the apical part of the 26S proteasome above the central opening in the AAA-ATPase heterohexamer. Both subunits are approximately positioned on a line perpendicular to the axis of the 20S catalytic chamber. Rpn10 is located above Rpt4/Rpt5, and Rpn13 above the Rpt1/Rpt2 heterodimer. Using Dsk2 as a label, we also determined the localization of the C-terminal UIM of Rpn10, which projects toward the N-terminal coiled coils of Rpt4/Rpt5.

NMR studies demonstrated that Rpn10/S5a and Rpn13 bind Ub chains simultaneously with a preference of Rpn10 for distal ubiquitin and of Rpn13 for proximal ubiquitin (12). It is also well established that at least four Ub molecules are required for efficient proteasome recognition (2, 3) and that Lys48-linked Ub chains adopt an open conformation in presence of Ub receptors (12, 41). Considering that the distance between the two Ub receptors in our EM structure is approximately 100 Å (Fig. 3A), one possible scenario is that this distance determines the minimum length for an Ub chain to be recognized by the proteasome (Fig. 4). Therefore, ubiquitin recognition may not only be mediated by increase of local Ub concentration but also spanning the distance between two receptors, which provides a tape measure for the length of the Ub chain. Further studies, for example, determining the structure of a polyubiquitin-bound form of 26S proteasome by using cryo-EM, are needed to examine this hypothesis.

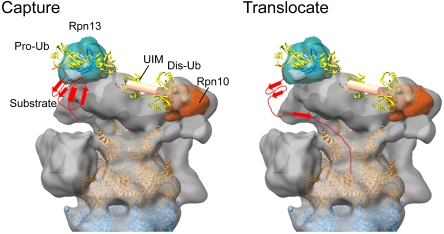

Fig. 4.

Hypothetical model of substrate recognition by the 26S proteasome. Capture: Polyubiquitylated substrates may be captured by both ubiquitin receptors Rpn10 and Rpn13. The C terminus of the proximal (pro-) ubiquitin is suspended from Rpn13 pointing toward the central opening of the AAA-ATPase ring. The distal (dis-) Ub is associated with the Rpn10 UIM. The Ub chain may span the distance between the two receptors. Translocate: The substrate is grabbed by the flexible coiled coils of the AAA-ATPase ring and partially unfolded for further translocation into the CP.

Functional Model of the 26S Proteasome from Ubiquitin Binding to Translocation.

It has been unclear how ubiquitylated substrates are bound to the 26S proteasome and then transferred into the central pore of the AAA-ATPases. The 26S proteasome binds ubiquitylated substrates in two steps (42): (i) initial binding to the Ub receptors via the polyubiquitin tag and (ii) tighter binding via a loosely folded substrate. The latter step is independent of ubiquitylation and requires ATP. The fit of Rpn13 into the EM map showed that the C terminus of the proximal ubiquitin is directed toward the central pore of the ATPase ring (Fig. 3B). Substrates conjugated to Ub may be suspended from Rpn13 and received by the flexible N-terminal coiled coils of the AAA-ATPases. Moreover, we have shown here that the Rpn10 UIM projects to the coiled coils of the AAA-ATPases. Thus, the positions of both Ub receptors are suitable for substrate transfer to the coiled coils of the AAA-ATPases. Indeed, the coiled coils of PAN have been shown to be responsible for recognition of partially folded substrates (43, 44) and enhance further unfolding of substrates (29, 45). Finally, it is noteworthy that Rpn11 is located near the mouth of the AAA-ATPases (28). Substrates that undergo unfolding are deubiquitylated by Rpn11, coupled with translocation into the CP for degradation (Fig. 4). Thus, the positions of both Ub receptors seem highly suitable to support the successive reactions from substrate recognition to protein unfolding and translocation into the CP.

Experimental Procedures

Yeast Strains.

Strains used in this study are listed in Table S1. All yeast manipulations were carried out as described previously (46).

Purification of 26S Proteasomes from S. cerevisiae.

The intact 26S proteasomes from wild-type and deletion strains were purified via RPN11-3xFLAG tag, as described previously (46). For enrichment, the eluted samples were subjected to a 15–40% sucrose gradient, subsequently fractionated, and analyzed by SDS-PAGE. The enriched fraction of the double-capped 26S proteasome was used for further analysis.

Affinity Purification and “Dsk2 Labeling” of 26S proteasomes from D. melanogaster.

Embryonic protein extract was prepared as described previously (47). The gene encoding the D. melanogaster ortholog of the yeast Dsk2 protein (CG14224; Ubiquilin) was PCR amplified by using the Drosophila L3 cDNA library as a template. The HindIII-SalI fragment encoding the N-terminal half of Dsk2 (Dsk2-NTH), which carries the Ubl domain (1–231 bps), was subcloned into the pGEX-4T.1 vector (GE Healthcare). GST-Dsk2-NTH proteins were expressed and affinity purified by using a glutathione sepharose column. Recombinant GST-Dsk2-NTH protein was immobilized on glutathione Sepharose 4B beads. Pupal extract was loaded with the beads and eluted with glutathione solution. Eluted proteins were analyzed by Coomassie blue stained SDS-PAGE.

Quantitative Mass Spectrometry.

The experiments were performed as previously described (27). The data analysis was performed with the MaxQuant software (48) and processed by a “label-free” proteomics approach (27). We determined the stoichiometry of the sample by normalizing the sum of all the identified peptides to the molecular mass of the individual proteins (27). The resulting intensities were standardized relative to the average intensity of the Rpt subunits.

Electron Cryomicroscopy.

Electron cryomicroscopy experiments were performed as previously reported (28). Low-dose images were taken on a Technai F20 electron microscope (FEI) at 200 kV equipped with an Eagle CCD camera at a magnification of 63,500. Final objective pixel size was 2.2 Å. The 4,000 micrographs were collected with a nominal defocus ranging from 1 to 3 μm.

Reconstruction and Classification.

The initial 3D model for refinement was the D. melanogaster 26S proteasome density (27) filtered to 4-nm resolution. The 3D reconstructions for the total set were performed in XMIPP (49). The final resolution was determined by using the FSC curve.

Maximum-likelihood classifications of the images were performed in the XMIPP package (50). For focused classification (28), angularly refined particles were C2 symmetrized, masked, and split into four or six iteratively optimized groups, respectively. The position and radius of the mask was determined by evaluating the variance map.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We thank C. Boulegue (Max-Planck Institute of Biochemistry) for mass spectrometry data analysis and R. Fernández-Busnadiego (Yale University) for critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by a postdoctoral fellowship of the Max-Planck Society (to E.S.), grants from the European Union Seventh Framework program Proteomics Specification in Space and Time (Grant HEALTH-F4-2008-201648) and SFB 594 of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (both to W.B.), the Human Frontier Science Project (Career Development Award to F.F.), the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan (K.T. and Y.S.), and the Targeted Research Program (K.T.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1119394109/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Buchberger A, Bukau B, Sommer T. Protein quality control in the cytosol and the endoplasmic reticulum: Brothers in arms. Mol Cell. 2010;40:238–252. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Deveraux Q, Ustrell V, Pickart C, Rechsteiner M. A 26S protease subunit that binds ubiquitin conjugates. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:7059–7061. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Piotrowski J, et al. Inhibition of the 26S proteasome by polyubiquitin chains synthesized to have defined lengths. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:23712–23721. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.38.23712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hershko A, Ciechanover A. The ubiquitin system. Annu Rev Biochem. 1998;67:425–479. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ikeda F, Dikic I. Atypical ubiquitin chains: New molecular signals ‘Protein Modifications: Beyond the Usual Suspects’ review series. EMBO Rep. 2008;9:536–542. doi: 10.1038/embor.2008.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peters JM, Cejka Z, Harris JR, Kleinschmidt JA, Baumeister W. Structural features of the 26S proteasome complex. J Mol Biol. 1993;234:932–937. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Voges D, Zwickl P, Baumeister W. The 26S proteasome: A molecular machine designed for controlled proteolysis. Annu Rev Biochem. 1999;68:1015–1068. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.68.1.1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Finley D. Recognition and processing of ubiquitin-protein conjugates by the proteasome. Annu Rev Biochem. 2009;78:477–513. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.78.081507.101607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van Nocker S, et al. The multiubiquitin-chain-binding protein Mcb1 is a component of the 26S proteasome in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and plays a nonessential, substrate-specific role in protein turnover. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:6020–6028. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.11.6020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Husnjak K, et al. Proteasome subunit Rpn13 is a novel ubiquitin receptor. Nature. 2008;453:481–488. doi: 10.1038/nature06926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schreiner P, et al. Ubiquitin docking at the proteasome through a novel pleckstrin-homology domain interaction. Nature. 2008;453:548–552. doi: 10.1038/nature06924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang N, et al. Structure of the s5a:k48-linked diubiquitin complex and its interactions with rpn13. Mol Cell. 2009;35:280–290. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang Q, Young P, Walters KJ. Structure of S5a bound to monoubiquitin provides a model for polyubiquitin recognition. J Mol Biol. 2005;348:727–739. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Glickman MH, et al. A subcomplex of the proteasome regulatory particle required for ubiquitin-conjugate degradation and related to the COP9-signalosome and eIF3. Cell. 1998;94:615–623. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81603-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fu H, Reis N, Lee Y, Glickman MH, Vierstra RD. Subunit interaction maps for the regulatory particle of the 26S proteasome and the COP9 signalosome. EMBO J. 2001;20:7096–7107. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.24.7096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen X, Lee BH, Finley D, Walters KJ. Structure of proteasome ubiquitin receptor hRpn13 and its activation by the scaffolding protein hRpn2. Mol Cell. 2010;38:404–415. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hamazaki J, et al. A novel proteasome interacting protein recruits the deubiquitinating enzyme UCH37 to 26S proteasomes. EMBO J. 2006;25:4524–4536. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yao T, et al. Proteasome recruitment and activation of the Uch37 deubiquitinating enzyme by Adrm1. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:994–1002. doi: 10.1038/ncb1460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lam YA, Xu W, DeMartino GN, Cohen RE. Editing of ubiquitin conjugates by an isopeptidase in the 26S proteasome. Nature. 1997;385:737–740. doi: 10.1038/385737a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen L, Shinde U, Ortolan TG, Madura K. Ubiquitin-associated (UBA) domains in Rad23 bind ubiquitin and promote inhibition of multi-ubiquitin chain assembly. EMBO Rep. 2001;2:933–938. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kve203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bertolaet BL, et al. UBA domains of DNA damage-inducible proteins interact with ubiquitin. Nat Struct Biol. 2001;8:417–422. doi: 10.1038/87575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Funakoshi M, Sasaki T, Nishimoto T, Kobayashi H. Budding yeast Dsk2p is a polyubiquitin-binding protein that can interact with the proteasome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:745–750. doi: 10.1073/pnas.012585199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wilkinson CR, et al. Proteins containing the UBA domain are able to bind to multi-ubiquitin chains. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:939–943. doi: 10.1038/ncb1001-939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gomez TA, Kolawa N, Gee M, Sweredoski MJ, Deshaies RJ. Identification of a functional docking site in the Rpn1 LRR domain for the UBA-UBL domain protein Ddi1. BMC Biol. 2011;9:33. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-9-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang D, et al. Together, Rpn10 and Dsk2 can serve as a polyubiquitin chain-length sensor. Mol Cell. 2009;36:1018–1033. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lipinszki Z, et al. Developmental-stage-specific regulation of the polyubiquitin receptors in Drosophila melanogaster. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:3083–3092. doi: 10.1242/jcs.049049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nickell S, et al. Insights into the molecular architecture of the 26S proteasome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:11943–11947. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905081106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bohn S, et al. Structure of the 26S proteasome from Schizosaccharomyces pombe at subnanometer resolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:20992–20997. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1015530107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Djuranovic S, et al. Structure and activity of the N-terminal substrate recognition domains in proteasomal ATPases. Mol Cell. 2009;34:580–590. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang F, et al. Structural insights into the regulatory particle of the proteasome from Methanocaldococcus jannaschii. Mol Cell. 2009;34:473–484. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Forster F, Lasker K, Nickell S, Sali A, Baumeister W. Toward an integrated structural model of the 26S proteasome. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2010;9:1666–1677. doi: 10.1074/mcp.R000002-MCP201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Saeki Y, Isono E, Toh EA. Preparation of ubiquitinated substrates by the PY motif-insertion method for monitoring 26S proteasome activity. Methods Enzymol. 2005;399:215–227. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(05)99014-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sakata E, et al. The catalytic activity of ubp6 enhances maturation of the proteasomal regulatory particle. Mol Cell. 2011;42:637–649. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Peth A, Besche HC, Goldberg AL. Ubiquitinated proteins activate the proteasome by binding to Usp14/Ubp6, which causes 20 S gate opening. Mol Cell. 2009;36:794–804. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.da Fonseca PC, Morris EP. Structure of the human 26S proteasome: Subunit radial displacements open the gate into the proteolytic core. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:23305–23314. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802716200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Riedinger C, et al. Structure of Rpn10 and its interactions with polyubiquitin chains and the proteasome subunit Rpn12. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:33992–34003. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.134510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Seeger M, et al. Interaction of the anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome and proteasome protein complexes with multiubiquitin chain-binding proteins. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:16791–16796. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208281200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Takeuchi J, Fujimuro M, Yokosawa H, Tanaka K, Toh-e A. Rpn9 is required for efficient assembly of the yeast 26S proteasome. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:6575–6584. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.10.6575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xie Y, Varshavsky A. Physical association of ubiquitin ligases and the 26S proteasome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:2497–2502. doi: 10.1073/pnas.060025497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pathare GR, et al. The proteasomal subunit Rpn6 is a molecular clamp holding the core and regulatory subcomplexes together. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1117648108. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dickinson BC, Varadan R, Fushman D. Effects of cyclization on conformational dynamics and binding properties of Lys48-linked di-ubiquitin. Protein Sci. 2007;16:369–378. doi: 10.1110/ps.062508007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Peth A, Uchiki T, Goldberg AL. ATP-dependent steps in the binding of ubiquitin conjugates to the 26S proteasome that commit to degradation. Mol Cell. 2010;40:671–681. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Reuter CJ, Kaczowka SJ, Maupin-Furlow JA. Differential regulation of the PanA and PanB proteasome-activating nucleotidase and 20 S proteasomal proteins of the haloarchaeon Haloferax volcanii. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:7763–7772. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.22.7763-7772.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang X, et al. The N-terminal coiled coil of the Rhodococcus erythropolis ARC AAA ATPase is neither necessary for oligomerization nor nucleotide hydrolysis. J Struct Biol. 2004;146:155–165. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2003.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang F, et al. Mechanism of substrate unfolding and translocation by the regulatory particle of the proteasome from Methanocaldococcus jannaschii. Mol Cell. 2009;34:485–496. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Saeki Y, Toh EA, Kudo T, Kawamura H, Tanaka K. Multiple proteasome-interacting proteins assist the assembly of the yeast 19S regulatory particle. Cell. 2009;137:900–913. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Udvardy A. Purification and characterization of a multiprotein component of the Drosophila 26S (1500 kDa) proteolytic complex. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:9055–9062. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cox J, Mann M. MaxQuant enables high peptide identification rates, individualized p.p.b.-range mass accuracies and proteome-wide protein quantification. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:1367–1372. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Scheres SH, Nunez-Ramirez R, Sorzano CO, Carazo JM, Marabini R. Image processing for electron microscopy single-particle analysis using XMIPP. Nat Protoc. 2008;3:977–990. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Scheres SH, et al. Disentangling conformational states of macromolecules in 3D-EM through likelihood optimization. Nat Methods. 2007;4:27–29. doi: 10.1038/nmeth992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.