Abstract

Efficient approaches for the precise genetic engineering of human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs) can enhance both basic and applied stem cell research. Adeno- associated virus (AAV) vectors are of particular interest for their capacity to mediate efficient gene delivery to and gene targeting in various cells. However, natural AAV serotypes offer only modest transduction of human embryonic and induced pluripotent stem cells (hESCs and hiPSCs), which limits their utility for efficiently manipulating the hPSC genome. Directed evolution is a powerful means to generate viral vectors with novel capabilities, and we have applied this approach to create a novel AAV variant with high gene delivery efficiencies (~50%) to hPSCs, which are importantly accompanied by a considerable increase in gene-targeting frequencies, up to 0.12%. While this level is likely sufficient for numerous applications, we also show that the gene-targeting efficiency mediated by an evolved AAV variant can be further enhanced (>1%) in the presence of targeted double- stranded breaks (DSBs) generated by the co-delivery of artificial zinc finger nucleases (ZFNs). Thus, this study demonstrates that under appropriate selective pressures, AAV vectors can be created to mediate efficient gene targeting in hPSCs, alone or in the presence of ZFN- mediated double-stranded DNA breaks.

Introduction

The capacity to mediate high efficiency gene delivery to human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs) has numerous applications, ranging from the study of specific genes in stem cell self-renewal and differentiation to the directed differentiation of stem cells into specific lineages for therapeutic application. Furthermore, precise manipulation of the human stem cell genome using gene- targeting techniques that exploit the natural ability of cells to perform homologous recombination (HR) has broad applications and implications, including safe harbor integration of genes for basic or therapeutic application, creating in vitro models for investigating human development and disease, and high-throughput drug discovery and toxicity studies.1,2 However, while gene delivery and gene targeting are well established for various mammalian somatic cells,3 a readily generalized approach for efficient gene expression and gene targeting in hPSCs requires further development.

Current methods to deliver genes to hPSCs range from viral vectors to plasmid-based transient gene expression. Lentiviral vectors—which are highly efficient and result in long-term gene expression—have been extensively employed in numerous studies in human stem cells.4 However, transient expression is desirable in some cases, such as for the temporary overexpression of regulatory signals to manipulate stem cell fate decisions.5,6 Also, vector integration into the genome can risk insertional mutagenesis, a potential concern for downstream clinical application.4 As an alternative, electroporation can be used to achieve transient gene expression, though this method can suffer from low transfection efficiencies and moderate toxicity in human stem cells.7 In addition to gene delivery, there is a need to develop efficient gene-targeting methods that rely on HR to introduce permanent and sequence-specific genome modifications in hPSCs. Several impressive studies have demonstrated successful gene targeting in hPSCs, though the initial rates reported using conventional methodologies are low (10−7–10−5 correctly targeted cells for every original cell in the population), which necessitates the use of positive and negative selection to improve the overall efficiency and specificity of the process.8,9

Recently, several approaches have been utlized to improve gene targeting in hPSCs, including the introduction of double-stranded breaks (DSBs) into the cellular genome by engineered nucleases.10,11,12,13,14 Such breaks stimulate the cellular DNA repair machinery and thereby greatly enhance the rate of homologous recombination with a donor DNA.15 For example, Zou et al. found that cotransfection of plasmids containing the donor DNA and zinc finger nucleases (ZFNs) significantly increased gene targeting in hPSCs up to a frequency of 0.24% (~1 targeted cell in 415 original cells), as compared to less than 1 targeted cell per 106 original cells in the absence of the ZFNs.13 More recently, a new approach has been described to engineer DNA-binding specificities based on transcription activator–like effector (TALE) proteins from Xanthomonas plant pathogens and artificial restriction enzymes generated by fusing TALEs to the catalytic domain of FokI was used to generate discrete edits or small deletions within endogenous human genes at efficiencies of up to 25%.16 However, while the utilization of ZFNs and transcription activator–like effector nucleases (TALENs) to enhance gene-targeting efficiencies in hPSCs is highly promising, the approach entails custom engineering of a new nuclease for each new target locus, which requires labor, time, and resources.

Adeno-associated virus (AAV) is a nonpathogenic, nonenveloped virus containing a 4.7 kb single-stranded DNA genome that encodes the structural proteins of the viral capsid (encoded by the cap gene) and the nonstructural proteins necessary for viral replication and assembly (encoded by the rep gene), flanked by short inverted terminal repeats.17 Recombinant versions of AAV can be created by inserting a sequence of interest in place of rep and cap, and the resulting recombinant vectors can efficiently deliver a transgene and safely mediate long-term gene expression in dividing and nondividing cells of numerous tissues.17 Such AAV-based vectors have proven safe, efficient, and recently very effective for clinical application.18,19

An interesting property of AAV is that, as demonstrated by Russell and colleagues, AAV vector genomes carrying gene-targeting constructs can mediate HR with target loci in a cellular genome at efficiencies 103–104-fold higher than plasmid constructs.3 The AAV genome's inverted terminal repeats, which apparently mediate its entry into the RAD51/RAD54 component of the cellular HR pathway, play a central role in this property.20 AAV-mediated gene targeting has been successfully applied to cells that AAV can effectively transduce, but naturally occurring AAV variants are typically inefficient at infecting a number of stem cell types, particularly human embryonioc stem cells (hESCs).21,22

We have implemented directed evolution—a rapid, high-throughput selection approach to create and isolate novel mutants from millions of genetic variants—to rapidly engineer AAV variants with desired gene delivery properties in the absence of the extensive mechanistic information typically required for rational biomolecular design. Recent work highlights the ability to apply directed evolution to create AAV mutants with altered receptor binding, neutralizing antibody-evasion properties, and altered cell tropism in vitro and in vivo.23,24,25,26,27,28,29 Likewise, we have recently demonstrated that directed evolution can yield novel AAV variants that enhance gene delivery and gene targeting in neural stem cells.21 Here, we implement this approach to create new AAV mutants with the enhanced capacity to infect and, subsequently, increase the efficiency of AAV-mediated gene targeting in hPSCs, both in the presence and absence of ZFN-mediated double-stranded DNA breaks.

Results

Evaluation of wild-type serotypes

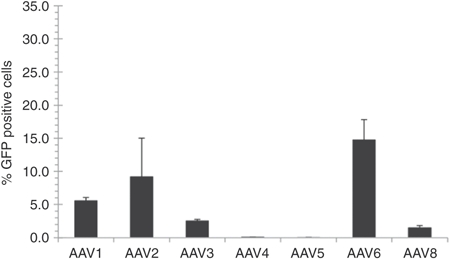

There are numerous naturally occurring AAV variants and serotypes, each of which has different protein capsids and thus somewhat different gene delivery properties for various cell types and tissues.30 AAV serotypes 1–6 and 8 were tested to assess their potential for hESC gene delivery. Initially, HSF-6 hESCs were infected with AAV vectors carrying green fluorescent protein (GFP) complementary DNA at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 10,000, and 48 hours postinfection, flow cytometry was used to determine the percentage of cells that express GFP and were thus infected by AAV. The most efficient was AAV6 (Figure 1); however, its low delivery efficiency (14.75 ± 3.08% GFP positive cells) places significant limitations on the fraction of cells that express a transgene or could undergo gene targeting. These results are consistent with earlier reports showing that natural AAV serotypes are typically inefficient in gene delivery to human stem cells,31,32 thus demonstrating the need to find, or evolve, an AAV variant capable of more efficient transduction.

Figure 1.

Gene expression in hESCs mediated by various AAV serotypes. HSF-6 cells were infected with numerous natural AAV serotypes at a MOI of 10,000. Transduction efficiency was assessed as the percentage of GFP positive cells measured by flow cytometry 48 hours postinfection. Error bars indicate standard deviation (n = 3). AAV, adeno-associated virus; GFP, green fluorescent protein; hESC, human embryonic stem cell; MOI, multiplicity of infection.

AAV library generation and selection through directed evolution

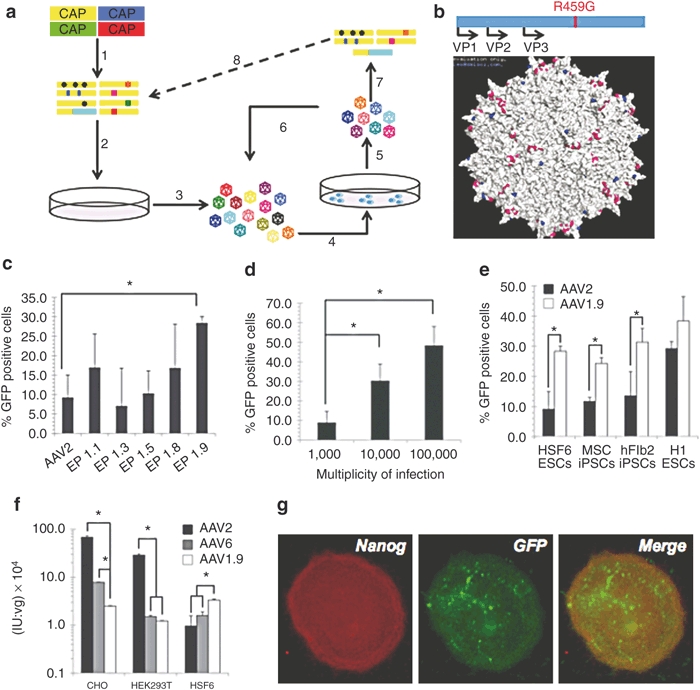

The AAV capsid proteins, encoded by the cap gene, determine the virus' ability to infect cells through their initial binding to various cell-surface receptors, intracellular trafficking, and entry into the nucleus. Directed evolution is a high-throughout approach that involves the creation and functional selection of libraries of genetic mutants to isolate novel variants with desirable properties. We implemented a directed evolution strategy to create AAV variants capable of mediating efficient gene delivery to hESCs (Figure 2a). Briefly, hESCs were infected with pools of virus variants created using several different techniques: a library in which AAV2 and AAV6 cap were subjected to error-prone PCR, a “shuffled” library composed of random cap chimeras of seven parent AAV serotypes,24 an AAV2 cap library with random 7-mer inserts,33 and AAV2 cap with substituted loop regions.25 Following infection with AAV libraries (Figure 2a, step 4) and amplification of the infectious AAV variants through adenovirus superinfection—as AAV requires a helper virus such as adenovirus to induce replication—(step 5), the resulting titre of AAV rescued from each library condition was quantified and compared to titres of recovered wild-type AAV2 as a metric for relative success of the selection. For each selection step, viral pools from the library produced higher viral titres than wild-type AAV2 at MOIs of both 10 and 100 (data not shown). These viral pools were then used as the starting point for the subsequent selection step (step 6). After three such selection steps, the successful viral cap genes were isolated (step 7) and tested individually to identify variants with the most efficient gene delivery. In addition, the cap genes isolated after the third selection step were subjected to an additional round of evolution, i.e., additional mutagenesis (step 8) and three selection steps, to further increase the fitness of the pool.

Figure 2.

Directed evolution of AAV and hPSC transduction by AAV 1.9. (a) Schematic representation of directed evolution. 1) A viral library is created by mutating the cap gene. 2) Viruses are packaged in HEK293T cells using plasmid transfection, such that each particle is composed of mutant capsid surrounding the cap gene encoding that protein capsid. 3) Viruses are harvested from 293 cells and purified. 4) The viral library is introduced to the HSF-6 hESCs in vitro. 5) Successful viruses are amplified and recovered using adenovirus rescue. 6) Successful clones are enriched through repeated selections. 7) Isolated viral DNA reveals selected cap genes. 8) Selected cap genes are mutated again to serve as a new starting point for selection. (b) Molecular model of the full AAV2 capsid, based on the solved structure,51 shows the location of the R459G mutation (blue) on the surface of the capsid (VP3 region), near the threefold axis of symmetry and residues known to be important for heparin and FGF receptor binding (pink). (c) AAV-mediated gene expression in hESCs. HSF-6 cells were infected with selected mutants at a MOI of 10,000. Transgene expression was assessed as the percentage of GFP positive cells measured by flow cytometry 48 hours postinfection. Error bars indicate the standard deviation (n = 3), *P < 0.01. (d) Elevating the MOI increases transduction. HSF-6 cells were infected with AAV1.9 at MOIs of 1,000, 10,000, and 100,000. Transgene expression was assessed as the percentage of GFP positive cells measured by flow cytometery 48 hours postinfection. Error bars indicate standard deviation (n = 3), *P < 0.01. (e) AAV1.9-mediated gene expression in hPSCs. HSF-6 hESCs, human dermal fibroblast-derived hiPSCs, human MSC-derived hiPSCs, and H1 hESCs were infected at a MOI of 10,000. Transgene expression was assessed as the percentage of GFP positive cells measured by flow cytometry 48 hours postinfection. Error bars indicate the standard deviation (n = 3), *P < 0.01. (f) In vitro analysis of AAV1.9 tropism. Variant AAV1.9 (white), selected on hESCs, is less infectious on AAV-permissive cell types (HEK293T, CHO) than recombinant AAV2 (black) and AAV6 (gray), but more infectious on HSF-6 hESCs. Error bars indicate standard deviation (n = 3), *P < 0.01. (g) HSF-6 cells infected by AAV1.9 maintain pluripotency marker expression. HSF-6 cells infected with AAV1.9 encoding GFP at an MOI of 100,000 were fixed and immunostained 1 week after infection for the presence of GFP (green) and the pluripotency marker Nanog (red). AAV, adeno-associated virus; FGF, fibroblast growth factor; GFP, green fluorescent protein; hESC, human embryonic stem cell; hiPSC, human induced pluripotent stem cell; MOI, multiplicity of infection; MSC, mesenchymal stem cell.

Increased transduction efficiency of the novel evolved AAV variant in hESCs

Nine cap variants from each library isolated after the third selection step of the first round of evolution were fully sequenced, and the AAV capsid protein variations and the frequency with which each clone was detected in the error-prone PCR-mutagenized AAV2 and AAV6 library are shown in Table 1. The cap genes of these variants were also used to package recombinant AAV carrying the GFP gene, under the control of the cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter. These recombinant AAV variants were then used to infect hESCs, and the gene delivery efficiency of each virus was measured via flow cytometry. Of the mutants isolated from the error-prone PCR-mutagenized AAV2 and AAV6 library, the variant AAV EP 1.9 (or AAV1.9), which carries a single-point mutation (R459G) (Figure 2b), showed the highest infection efficiency at 28.25 ± 1.68% GFP positive cells, representing an approximately threefold increase over AAV2 (its parental serotype) and a twofold increase over AAV6 (the best serotype) at an MOI of 10,000 (Figure 2c). Variants isolated from the shuffled, 7-mer insertion, and substituted loop region libraries were sequenced and analyzed as well. Variants from these libraries showed increased infection efficiency compared to AAV2, but not AAV6 (data not shown). At an MOI of 100,000, the variant AAV1.9 achieved a strong infection efficiency of 48.21 ± 12.92% GFP positive cells (Figure 2d). It should be noted that hESCs grow as colonies that are typically multilayered, making accessing and infecting all of the cells in a colony difficult. However, AAV1.9 provides an increase in gene delivery efficiency, by an increase in the number of cells infected (Figure 2c), an increase in the relative fluorescence intensity of infected cells (approximately threefold higher than AAV6), and a significantly increased number of donor DNA molecules delivered to each cell (Supplementary Materials and Methods and Supplementary Figure S1). Interestingly, sequencing of cap variants isolated after an additional round of mutagenesis to the cap library and three additional selection steps all matched the sequence of AAV1.9 (data not shown).

Table 1. Summary of variants isolated from three rounds of selection against hESCs.

AAV1.9 was isolated through multiple rounds of selection using the HSF-6 hESC line; however, the increase in gene delivery efficiency also extended to the broadly utilized H1 hESC line, as well as induced pluripotent cell lines including mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) -derived, and dermal fibroblast-derived hiPSC lines (Figure 2e).34 In addition, while AAV1.9 is capable of higher gene delivery efficiency to hESCs and hiPSCs, it is less infectious towards several cell types typically permissive to AAV infection (Figure 2f), indicating that in this case directed evolution yielded a variant that efficiently and somewhat selectively transduces an ordinarily nonpermissive cell. Furthermore, the hESCs maintained pluripotency marker expression following infection, assessed via Nanog immunostaining (Figure 2g).

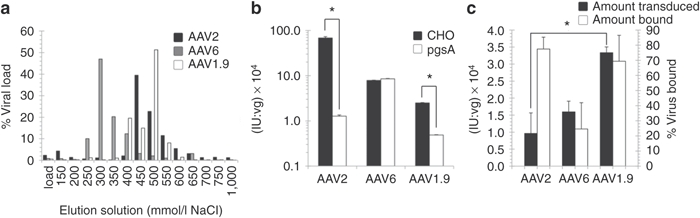

The R459G mutation in AAV1.9 lies close to but not within the heparin or fibroblast growth factor (FGF) receptor binding domains on the AAV capsid surface (Figure 2b), though it could conceivably modulate binding to the cell surface. To determine whether the amino acid 459 mutation alters the heparin-binding properties of the variant, AAV2, AAV6, and AAV1.9 were analyzed using heparin column chromatography, which can provide a measure of the heparin-binding affinity of AAV variants. Despite its mutation residing outside the reported heparin-binding domain,35 and despite the loss of a positively charged residue, AAV1.9 displays a higher affinity for heparin compared to the parental serotype AAV2, as indicated by the higher NaCl concentration needed to elute the majority of AAV1.9 from the heparin column. (Figure 3a). However, in vitro transduction of CHO and pgsA (a mutant CHO cell line lacking surface glycosaminoglycans (GAGs)) cells showed that AAV1.9 had less dependence on cell-surface heparan sulfate proteoglycans (AAV2's primary receptor)36 for cell transduction (Figure 3b). Furthermore, while it exhibited higher transduction levels, AAV1.9 bound to hESCs at levels similar to AAV2 (Figure 3c). Collectively, these data indicate that the R459G mutation may exert its effects after initial docking to the cell surface, though future studies will be needed to elucidate its mechanism of enhanced hESC infection.

Figure 3.

Mechanistic analysis of transduction by variant AAV. (a) AAV1.9 has a higher affinity for heparin than AAV2 and AAV6. The heparin affinity column chromatogram of recombinant AAV2 (black), AAV6 (gray), and AAV1.9 (white) is shown, where virus was eluted from the column using increasing concentrations of NaCl. Virus was quantified using qPCR. (b) In vitro characterization of AAV1.9 HSPG dependence. CHO (black) and pgsA (white) cells were transduced to demonstrate the decrease in HSPG dependence of AAV1.9 compared to AAV2. Error bars indicate standard deviation (n = 3), *P < 0.01. AAV, adeno-associated virus; hESC, human embryonic stem cell, qPCR, quantitative PCR. (c) In vitro characterization of AAV1.9 binding affinity. AAV1.9 and its parental serotype AAV2 bind hESCs to similar extents, yet AAV1.9 is capable of significantly higher transduction of hESCs. Error bars indicate standard deviation (n = 3), *P < 0.01.

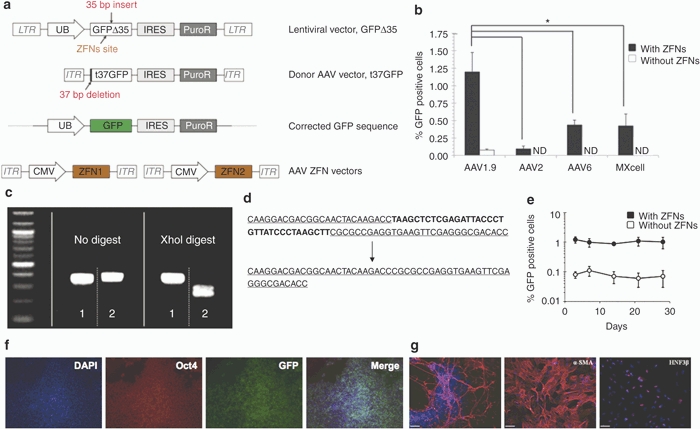

Enhanced gene-targeting efficiency of the novel evolved AAV variant in hESCs

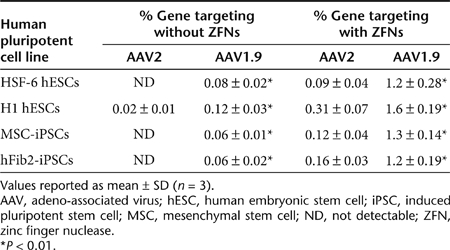

We assessed the ability of the novel variant to mediate gene targeting in hPSCs. To do so, we employed a mutated GFP-based reporter system, previously described by Zou et al.13 Briefly, GFP complementary DNA containing a 35 bp insertion harboring a stop codon (GFPΔ35) was introduced into HSF-6 hESCs using a lentiviral vector (see Materials and Methods and Figure 4a). The donor construct (t37GFP) consisted of a promoter-less, nonfunctional GFP with a 37 bp 5′ truncation, as well as 290 nucleotides of homology upstream and 1,619 nucleotides downstream of the 35 bp insertion in GFPΔ35. The donor plasmid was packaged into recombinant AAV vectors (AAV2, AAV6, and AAV1.9), and a hESC line carrying the mutated GFP was infected with these gene-targeting constructs to test their capacity to mediate gene correction and thereby restore GFP fluorescence. The levels of gene correction achieved using recombinant AAV2 and AAV6 were below the limits of detection of flow cytometry in this assay (Figure 4b), whereas the variant AAV1.9 was capable of targeted gene correction resulting in fluorescent hESCs (0.12%). Furthermore, consistent with previous reports,3 we also show that at similar efficiencies of gene delivery, AAV vectors can mediate targeted gene correction at rates much higher than plasmid constructs (Figure 4b). Moreover, as discussed earlier, AAV1.9 is also capable of higher gene delivery efficiency to H1 hESCs, and MSC- and dermal fibroblast-derived hiPSCs (Figure 2e), and we observe a corresponding increase in gene-targeting efficiencies (0.06–0.12%) for these cell lines as well (Table 2).

Figure 4.

AAV1.9-mediated correction of a nonfunctional GFP expressed in hESCs. (a) Schematic overview depicting the targeting strategy for the GFP gene correction. The defective GFP gene—GFPΔ35, mutated by the insertion of a 35 bp fragment containing a translational stop codon13—was integrated into HSF-6 cells using a lentiviral vector. A targeting vector (t37GFP) containing a 5′ truncated GFP coding sequence was packaged into a recombinant AAV vector lacking a promoter. Homologous recombination between donor vector and integrated defective GFPΔ35 gene would correct the 35 bp mutation and result in fluorescent hESCs. (b) Gene targeting frequencies assessed as the percentage of GFP positive cells measured via flow cytometry 72 hours postinfection. Error bars indicate standard deviation (n = 3), *P < 0.01. ND, not detectable by flow cytometry. (c,d) Representative analyses of the targeted correction of GFPΔ35 gene. Genomic DNA from the “corrected” and “uncorrected” HSF-6 cells was amplified using PCR. The 35 bp mutation within the GFPΔ35 gene contains an Xho I site, and therefore only the PCR products from the “uncorrected” cells (sample 2) can be digested using Xho I, whereas the PCR products from the corrected cells (sample 1) show the restoration of the functional GFP gene without the Xho I site. DNA sequencing analysis also shows AAV1.9-mediated correction of the 35 bp mutation in HSF-6 cells originally expressing the mutated GFPΔ35 gene. (e) Time course of AAV-mediated GFPΔ35 correction in HSF-6 cells. Error bars indicate standard deviation (n = 3). (f) Maintenance of an undifferentiated state of gene-corrected, GFP-expressing cells for 30 days postinfection. GFP positive HSF-6 cells, isolated via FACS, were cultured for 30 days, then fixed and probed for the presence of GFP (green), Oct4 (red), and DAPI (blue). (g) Pluripotency of the HSF-6 cells carrying the corrected GFP gene was further confirmed through embryoid body-mediated in vitro differentiation to generate derivatives of all three germ layers, as indicated by the expression of the ectodermal marker β-III tubulin, the mesodermal marker α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA), and the endodermal marker hepatocyte nuclear factor 3 β (HNF3β) after 24 days of differentiation (Bar = 100 µm). AAV, adeno-associated virus; CMV, cytomegalovirus; DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; FACS, fluorescent-activated cell sorting; GFP, green fluorescent protein; hESC, human embryonic stem cell; IRES, internal ribosome entry site; ITR, inverted terminal repeat; LTR, long terminal repeat.

Table 2. Summary of gene targeting experiments and rates in various human pluripotent lines in the presence and absence of ZFN-mediated DSBs.

Introduction of DSBs via ZFNs improves the gene-targeting efficiencies of AAV vectors

Directed evolution thus created a novel AAV variant that mediates high levels of gene targeting in hESCs and hiPSCs, and previous reports indicate that in addition to enhancing the ability of the donor DNA to mediate HR, complementary approaches such as inducing local DSBs at the target locus can further enhance gene targeting.37 Recent years have witnessed the development of engineered restriction enzymes generated by fusing a DNA cleavage domain either to a zinc finger or a TAL effector DNA-binding domain as a general approach to generate site-specific double-stranded chromosomal breaks and thereby greatly stimulate homology-directed gene repair in a number of human cell lines.10,11,12,13,16 These findings provided rationale to explore whether stimulation of gene targeting by nuclease-mediated DSBs can be combined with an evolved AAV to further enhance gene targeting in hPSCs. We first generated AAV vectors that expressed the ZFNs from a CMV promoter to target a site 12 bp upstream of the 35 bp insertion in the GFP gene (Figure 4a).38 hPSCs harboring the mutant GFP were infected with the two AAV vectors encoding a GFP-specific ZFN, as well as the AAV donor vector (t37GFP), and the gene-targeting efficiency was measured via flow cytometry to detect cells expressing the corrected GFP. In the presence of a local DSB-mediated by ZFNs, we observe a fivefold to 13-fold increase in AAV1.9-mediated gene-targeting rates (Figure 4b and Table 2), from an already relatively high efficiency of 0.06–0.12% to 1.2–1.6% across multiple hPSC lines. Also, while not as high as with AAV1.9, using other AAV serotypes to deliver the donor construct and ZFNs did yield measurable gene correction in all cases, indicating the generality of using AAV to deliver both donor and nuclease for enhanced HR (Figure 4b and Table 2). Finally, we observed similar increases in gene-targeting efficiencies when we infected human pluripotent embryonic carcinoma cells (NT2) and human embryonic kidney (HEK293T) cells harboring the mutant GFP with AAV2 vectors encoding the GFP-specific ZFN and the donor t37GFP plasmids, indicating the general utility of combining an AAV donor with DSBs at the target locus (Supplementary Figure S2).

To verify correction of the GFPΔ35 sequence, genomic DNA from “corrected” (GFP positive cells isolated using fluorescence-activated cell sorting) and “uncorrected” HSF-6 hESCs was subjected to PCR to amplify the GFP sequence. The 35 bp insert of the mutated GFP cell line harbors a unique Xho I site that enabled the confirmation of GFP correction by restriction digest analysis (Figure 4c). Also, direct sequencing of the PCR fragments confirmed the correction of the mutated GFPΔ35 gene (Figure 4d). Furthermore, the GFP positive hESCs, purified via fluorescence-activated cell sorting, were expanded and monitored by flow cytometry for 30 days, and >95% of cells maintained GFP expression (Figure 4e). These cells also maintained a pluripotent state during long-term culture following targeted gene correction as indicated by the expression of the pluripotency marker Oct4 (Figure 4f) and their ability to differentiate into cells originating from the three germ layers via embryoid body formation in vitro (Figure 4g).

Finally, in addition to measuring targeted gene correction via HR, we also assessed the frequency of random chromosomal integration of AAV1.9 vectors. HSF-6 hESCs harboring GFPΔ35 were infected with AAV1.9 donor constructs and cultured for 14 days. The genomic DNA from the infected cells was subjected to PCR to specifically amplify a 822 bp fragment that partially spanned the AAV viral genome following the puromycin resistance gene (Supplementary Figure S3a), a region that should not participate in homologous recombination (Figure 4a) and would thus represent residual AAV sequence. This assay was calibrated by conducting PCR in parallel on naive hESC DNA samples spiked with different amounts of AAV1.9 donor plasmid, ranging from 1 copy of AAV plasmid per 400 cellular genome copies to 1 copy of AAV plasmid per 20 cellular genome copies. Based on the quantification of the samples and the standards, ~1 copy of AAV1.9 genome was present per 100 cells that were originally exposed to the vector (Supplementary Materials and Methods and Supplementary Figure S3b), consistent with earlier reports that demonstrate low risk of random genomic integration of AAV in human cells.37,39 To determine whether introduction of site-specific DSBs using ZFNs increases this low frequency of random integration, we coinfected hESCs carrying the mutant GFP with AAV1.9 vectors encoding the donor plasmid, as well as the GFP-specific ZFNs. We did not observe a significant increase in the levels of random integration in the presence of ZFNs (Supplementary Figure S3), which suggests that at least in this system the introduction of site-specific DSBs may not have a strong effect on nonhomologous integration frequencies of AAV vectors.37,39

Discussion

AAV has attracted increasing attention for its ability to safely and efficiently mediate gene targeting in a variety of cell types.3,30,32 However, prior studies have indicated that naturally occurring AAV serotypes are typically inefficient in transducing numerous classes of stem cells, which can limit also the application of AAV-mediated gene targeting to hPSCs. Recently, two studies have reported the natural serotype AAV3 as the most efficient serotype for human pluripotent lines.31,40 In the hESC and hiPSC cell lines we examined, we did not observe a higher efficiency for AAV3 relative to other serotypes (Figure 2c and data not shown). Moreover, the reported transduction efficiency for AAV3 in the earlier studies was lower than 25% at a MOI of 200,000, and likely as a result, the maximum reported gene-targeting frequency was 1.3 × 10−5.31 Collectively, these results indicate that different natural serotypes may be suited for different hPSC lines, but importantly that gene-targeting efforts in general may benefit from increasing AAV's delivery efficiency to hPSCs.

Directed evolution has proven to be a powerful approach to create AAV vectors with novel capabilities, and we successfully demonstrate that under appropriate selective pressures AAV can evolve for improved transduction efficiencies in human pluripotent stem cells. Specifically, we isolated a new AAV variant, AAV1.9, that exhibited an enhanced infection efficiency of ~48% at a MOI of 100,000. AAV1.9 harbors a single R459G mutation that lies in close proximity to both the heparin and FGF receptor binding domains of AAV2. This variant displayed a slightly higher affinity for heparin compared to AAV2 (Figure 3a), though we observed similar levels of AAV1.9 and AAV2 binding to hESCs (Figure 3c). In their investigation of AAV2's heparin-binding domain, Opie et al. found that a R459A AAV2 mutant was incapable of infecting HeLa cells, despite heparin-binding levels essentially the same as AAV2.41 The authors hypothesized that the R459A mutation may result in a defect in a later stage of viral infection.41 This finding, in conjunction with our observations that similar percentages of AAV2 and AAV1.9 bind to hESCs, suggests that the R459G mutation may increase hESC gene delivery by modulating viral infection at a point following initial cell-surface docking, for example AAV structural rearrangement during heparan sulfate binding,42 subsequent binding to secondary receptors, or cellular entry. Further studies are needed to elucidate such mechanisms.

An AAV variant with enhanced gene delivery to hESCs can serve as a valuable tool for numerous applications. For example, AAV could mediate the controlled overexpression of regulatory proteins, short hairpin RNAs, or microRNAs, which would enable basic investigations of the roles of key factors in stem cell self-renewal or lineage commitment, as well as therapeutic applications that rely on the efficient generation of specific cell lineages. AAV has the potential to remain episomal and thereby mediate transient expression of such factors, compared to typically constitutive expression from lentiviral vectors, which may in some cases be advantageous. Furthermore, increased gene delivery efficiencies afford the opportunity to deliver multiple cargos effectively. For example, a twofold increase in the delivery of one AAV vector would translate to an eightfold increase in the number of cells that would be transduced with three vectors carrying three different transgenes (such as the gene-targeting construct and two ZFN-encoding vectors utilized in this study). Another consequence of generating AAV variants with higher transduction efficiencies in stem cells is the corresponding increase in gene-targeting efficiencies. When AAV1.9 was used to mediate gene correction in HSF-6 hESCs, we observed gene- targeting frequencies of 8 × 10−4, approximately tenfold higher than the reported targeting frequencies mediated by naturally occurring AAV serotypes.31,32 We have also observed that AAV1.9 allows for increased gene delivery and gene-targeting efficiencies to the H1 hESC line, as well as dermal fibroblast- and MSC-derived iPSCs, thus establishing the generality of the method.

It was previously shown that AAV gene targeting could be enhanced with a double-stranded DNA break introduced at the target locus by the nuclease I-SceI,37,39 and our results build upon this important prior work to show for the first time that AAV can function effectively in conjunction with ZFNs, which can now be engineered for genomic site specificity.10,12,13 In addition to ZFNs, TALE truncation variants have recently been linked to the catalytic domain of Fok I to yield a new class of nucleases that can generate discrete edits or small deletions within endogenous human genes and induce gene modification in human cells by both nonhomologous end joining and HR.16 Alternatively, the DNA recognition properties of homing endonucleases can be re-engineered to yield enzymes that recognize endogenous genes in human cells.43 Such custom nucleases can be beneficial, as prior studies indicate that gene-targeting frequencies vary from locus to locus and are lower at nonexpressed genes,12,44 and the targeting efficiencies in this study may have benefitted from the use of a lentiviral vector—which preferentially integrates into active transcription units45—as the target locus. Furthermore, researchers have observed that gene correction, gene knock-in, and knock-out vectors exhibit varying targeting frequencies.46,47 However, depending on the application, it is important to note that an appropriate AAV has the potential to mediate gene targeting at a given locus at rates that are sufficiently high to obviate the time, labor, and resources entailed in generating a custom nuclease. Furthermore, as ZFNs and other nucleases have the potential to exhibit off-target cleavage,48,49 the use of effective donor DNA in the absence of DSBs offers certain advantages.

In conclusion, we have used directed evolution to create a novel AAV variant with a single-point mutation that exhibited enhanced gene delivery efficiency, and subsequently gene targeting, in hPSCs. In addition, this work demonstrates that AAV-mediated gene-targeting frequencies can be further enhanced in the presence of targeted DSBs generated by the AAV vector co- delivery of ZFNs. These findings suggest that AAV vectors may find strong utility in investigations of stem cell biology and therapy, ranging from the generation of reporter cell lines to therapeutic gene correction.

Materials and Methods

Cell lines. Cell lines were cultured at 37 °C and 5% CO2 and, unless otherwise mentioned, were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). HEK293T and NT2 cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco, Carlsbad, CA) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). CHO K1 and CHO pgsA cells were cultured in F-12K medium (ATCC) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Invitrogen). HSF-6 hESCs (UC San Francisco) were cultured on Matrigel-coated cell culture plates (BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ) in X-Vivo medium (Lonza, Norwalk, CT) supplemented with 80 ng/ml FGF-2 (PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ) and 0.5 ng/ml TGF-β1 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). H1 hESCs (WiCell, Madison, WI) and dermal fibroblast- and MSC-derived iPS cells (a kind gift from George Q. Daley, Children's Hospital Boston, Boston, MA) were cultured on Matrigel-coated cell culture plates (BD) in mTeSR1 maintenance medium (Stem Cell Technologies, Seattle, WA).

Library generation and viral production. Four replication-competent viral libraries were used as starting materials for selections on HSF-6 hESCs. A random mutagenesis library was generated by subjecting cap genes from AAV2 and AAV6 to error-prone PCR using 5′-CATGGGAAA GGTGCCAGACG-3′ and 5′-ACCATCGGCAGCCATACCTG-3′ as forward and reverse primers, respectively, as previously described (EP Library).23 Libraries consisting of AAV2 containing random 7-mer peptide inserts33 and AAV2 containing randomized cap loop regions25 were also utilized. Finally, a library containing shuffled DNA from the wild-type AAV1, AAV2, AAV4, AAV5, AAV6, AAV8, AAV9 cap genes was packaged.24 Libraries were pooled for the selection steps. Following evolution, to create recombinant versions of selected viruses, the cap genes were inserted into the pXX2 recombinant AAV packaging plasmid using Not I and Hind III.23 Both the replication-competent AAV library and recombinant AAV vectors expressing GFP under the control of a CMV promoter were packaged using HEK293T cells using the calcium phosphate transfection method, and the viruses were purified by iodixonal gradient centrifugation and Amicon filtration.23,27 DNase-resistant genomic titres were determined via quantitative PCR.23

Library selection and evolution. One selection step is defined as hESC infection using a starting library, rescue by addition of adenovirus serotype 5 (at levels sufficient to induce a cytopathic effect 48 hours post-adenovirus infection), and harvest of successful variants. For each selection step, cells were grown on Matrigel-coated plates to eliminate the use of feeder cells, which could become infected and bias the selection towards viral variants that transduce the feeder layer. In addition, stromal cells were removed from the culture using collagenase digestion before the viral harvest to prevent the selection of viral variants that infect stromal cells instead of hESCs. One round of evolution consists of genetic diversification of the cap gene followed by three selection steps. Two rounds of evolution were performed, with clonal analysis (cap gene sequencing and hESC gene delivery assay for each selected virus) performed between each round of evolution. Following the third selection step, AAV cap genes were isolated from the pool of successful AAV variants and amplified via PCR. Cap genes were then sequenced at the University of California, Berkeley DNA sequencing facility and analyzed using Geneious software (Biomatters, Auckland, New Zealand). Three-dimensional models of the AAV2 capsid (Protein Databank accession number 1LP3) were rendered in Pymol (DeLano Scientific, San Carlos, CA).

HPSC transduction analysis. The human pluripotent cell lines were plated at a density of 105 cells/well 24 hours before infection. Cells were infected with rAAV-GFP at an MOI of 104. Stromal cells were removed from the hESC and the iPSC culture using collagenase digestion before flow cytometry. The percentage of GFP positive cells was assessed 48 hours postinfection using a Beckman-Coulter Cytomics FC 500 flow cytometer (Beckman-Coulter, Brea, CA).

Immunofluorescence staining. Immunostaining was performed to visualize the expression of pluripotency markers following AAV infection and gene targeting. HSF-6 hESCs were plated on a 24-well plate and infected as described for the transduction analysis. Forty-eight hours postinfection, cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 minutes, washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and blocked with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) and 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS for 30 minutes. Cells were incubated overnight at 4 °C with a mouse anti-Oct-3/4 primary antibody (1:200 dilution, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) or anti-Nanog primary antibody (1:200 dilution, Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Cells were then washed three times with PBS and incubated with a secondary fluorescent-conjugated Alexa Fluor 647 goat anti-mouse antibody (1:250 dilution, Invitrogen) for 2 hours, followed by 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) for nuclear staining (Invitrogen) for 15 minutes. Cells were imaged using a Zeiss Axio Observer. A1 inverted microscope.

In vitro differentiation assay of pluripotency. Colonies of HSF-6 hESCs were isolated from stromal cells by collagenase enzymatic treatment and partially dissociated by gentle pipetting. The cells were cultivated as small clusters (5–10 cells) in suspension culture in ultra low-attachment plates (Corning, Corning, NY) to generate embryoid bodies (EBs) in X-Vivo medium. After 6 days, the EBs were transferred to plates precoated with Matrigel and further differentiated for 24 days. Immunocytochemistry as described above was used to investigate whether the cells express markers of the three germ layers using the following primary antibodies: ectodermal: rabbit anti-β-III tubulin (1:500 dilution; Covance, Princeton, NJ); mesodermal: mouse anti-α-smooth muscle actin (1:500 dilution; Sigma, St Louis, MO); endodermal: rabbit anti-hepatocyte nuclear factor 3 β (1:500 dilution; Millipore, Billerica, MA). Fluorescence images were acquired using a Nikon TE2000E2 epifluorescence microscope.

In vitro transduction and cell binding analysis. To determine the heparan sulfate dependence of AAV2 and the selected mutant, CHO K1 and CHO pgsA cells were plated at a density of 2.5 × 104 cells per well 24 hours before infection. Cells were infected with AAV2-GFP, AAV6-GFP, or AAV1.9-GFP at MOIs ranging from 100–2,500.26 The percentage of GFP positive cells was assessed 48 hours postinfection using a Beckman-Coulter Cytomics FC 500 flow cytometer.

To analyze cell-surface binding of AAV variants, cells were plated as described for the hESC transduction analysis. Stromal cells were removed from the hESC culture via collagenase digestion, and cells were incubated at 4 °C for 10 minutes; 105 cells were incubated with rAAV-GFP (MOI of 104) at 4 °C for 1 hour. Cells were washed twice with ice-cold PBS to remove unbound virus. DNase-resistant genomic titers were determined via quantitative PCR.

Heparin column chromatography. rAAV-GFP vectors were subjected to heparin column chromatography as previously described.23 Briefly, 1010 vector genome containing AAV particles were loaded into a 1 ml HiTrap heparin column (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ) previously equilibrated with 0.15 mol/l NaCl and 50 mmol/l Tris at pH = 7.5. Washes were performed using 1 ml volumes of Tris buffer containing increasing increments of 50 mmol/l NaCl, starting at 150 mmol/l NaCl and ending at 750 mmol/l NaCl, followed by a 1 mol/l NaCl wash. Genomic titres from each fraction were determined via quantitative PCR.

Generation of mutant GFP hPSC lines. An internal ribosome entry site and puromycin resistance gene cassette (IRES-PuroR) were cloned into the Eco RI and Xho I sites of pFUGW (a kind gift from David Baltimore, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA) to replace the woodchuck hepatitis virus post-transcriptional regulatory element (WPRE) and yield pFUGIP. Next, a mutant GFP sequence harboring a 35 bp insertion (GFPΔ35) (a kind gift from Matthew H. Porteus, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX) digested with Bam HI/Eco RI was inserted in place of the GFP sequence of similarly digested pFUGIP to construct pFUGΔ35IP. The lentiviral vector carrying the mutated GFP was packaged by the calcium phosphate transient transfection method.50 Briefly, 10 µg of pFUGΔ35IP, 5 µg of pMDL g/p PRE, 3.5 µg of pcDNA 3 IVS VSV-G, and 1.5 µg of pRSV Rev were transfected into HEK 293T cell lines (>70% confluency), which were cultured on 10 cm tissue culture plates under Iscove's modified Dulbecco's medium (IMDM) supplemented by 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. The lentiviral vector was harvested and concentrated by ultracentrifugation (L8-55M Ultracentrifuge; Beckman Coulter), followed by resuspension in 100 µl of PBS with 20% sucrose. Stable hPSC lines expressing the mutant GFP was generated by infection with the lentiviral vector, followed by puromycin selection (1 µg/ml) for 1 week. GFP fluorescence was not detected in the GFPΔ35 hPSCs, as confirmed by flow cytometry.

Gene targeting assay. The donor plasmid was generated by subcloning a truncated GFP gene missing the first 37 base pairs (t37GFP), internal ribosome entry site, and puromycin resistance gene cassette into an AAV vector plasmid (pAAV CMV GFP SN), such that the resulting targeting vector lacked a promoter. The ZFN expression constructs, driven by a CMV promoter, were generated by subcloning gene cassettes containing the engineered zinc fingers targeting GFP (also a gift from Matthew H. Porteus) into pAAV CMV GFP SN (detailed cloning steps for the donor and ZFN expressing constructs available upon request). The donor construct and the ZFN expressing constructs were then packaged into the AAV2, AAV6, and AAV1.9 capsids. All viral vectors were harvested and purified as described earlier.

For gene-targeting experiments mediated by AAV, hPSCs were seeded onto 12-well tissue culture plates at a density of 105 cells/well 24 hours before AAV infection. The cells were infected with the AAV targeting vectors at an MOI of 105. For targeting experiments in the presence of ZFNs, the ZFN expressing vectors were added at an MOI of 105 to the cells in addition to the AAV targeting vectors. For gene-targeting experiments mediated by naked plasmid constructs, Rho kinase inhibitor (ROCK inhibitor, Y-27632; CalBioChem, San Diego, CA) was added to hPSC media 24 hours before electroporation. Cells were harvested using collagenase digestion, resuspended at 106 cells/ml in 100 µl Bio-Rad buffer (GPEB 2) containing 1 µg each of the donor plasmid and ZFN expression plasmids, and electroporated using the Bio-Rad Gene Pulser MXcell System (250 V, 500 µF, 1000 ohms; Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). The cells were replated on Matrigel-coated plates in hPSC culture medium supplemented with ROCK inhibitor. The medium was replaced after 1 day. The percentage of GFP positive cells was assessed 48 hours postinfection using flow cytometry as described earlier.

Cell sorting and sequencing. Cells infected with AAV1.9 were cultured for 30 days and sorted at the UC Berkeley Cancer Center with a BD Influx Sorter to isolate GFP positive cells. For DNA sequencing analysis, cellular genomic DNA was extracted with the QIAamp DNA Micro Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) and amplified using 5′-CCACCCTCGTGACCACCCTG-3′ and 5′-CGGCCATGATATAGACGTTGTGGC-3′ primers. The resulting PCR products were cloned using the StrataCloneTM PCR cloning kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA), and individual clones were sequenced to confirm the gene correction.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL Figure S1. AAV1.9 increases the number of donor molecules per cell. Figure S2. AAV2-mediated correction of a nonfunctional GFP expressed in HEK293Ts and NT2s. Figure S3. Representative analysis of residual AAV1.9 genomes. Materials and Methods.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by CIRM Award RT1-01021 and an NSF Graduate Fellowship (M.A.B.). We thank Matthew H. Porteus (UT Southwestern) and Linzhao Cheng (JHU Medicine) for the mutated and donor GFP and GFP-ZFN plasmid constructs, and George Q. Daley (Children's Hospital Boston) for dermal fibroblast- and MSC-derived iPS cells. The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

AAV1.9 increases the number of donor molecules per cell.

AAV2-mediated correction of a nonfunctional GFP expressed in HEK293Ts and NT2s.

Representative analysis of residual AAV1.9 genomes.

REFERENCES

- Conrad C, Gupta R, Mohan H, Niess H, Bruns CJ, Kopp R.et al. (2007Genetically engineered stem cells for therapeutic gene delivery Curr Gene Ther 7249–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yates F., and, Daley GQ. Progress and prospects: gene transfer into embryonic stem cells. Gene Ther. 2006;13:1431–1439. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell DW., and, Hirata RK. Human gene targeting by viral vectors. Nat Genet. 1998;18:325–330. doi: 10.1038/ng0498-325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gropp M., and, Reubinoff B. Lentiviral vector-mediated gene delivery into human embryonic stem cells. Meth Enzymol. 2006;420:64–81. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(06)20005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan X, Valdimarsdottir G, Larsson J, Brun A, Magnusson M, Jacobsen SE.et al. (2002Transient disruption of autocrine TGF-beta signaling leads to enhanced survival and proliferation potential in single primitive human hemopoietic progenitor cells J Immunol 168755–762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hester ME, Song S, Miranda CJ, Eagle A, Schwartz PH., and, Kaspar BK. Two factor reprogramming of human neural stem cells into pluripotency. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e7044. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jo J., and, Tabata Y. Non-viral gene transfection technologies for genetic engineering of stem cells. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2008;68:90–104. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2007.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansour SL, Thomas KR., and, Capecchi MR. Disruption of the proto-oncogene int-2 in mouse embryo-derived stem cells: a general strategy for targeting mutations to non-selectable genes. Nature. 1988;336:348–352. doi: 10.1038/336348a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi K, Ohye T, Pastan I., and, Nagatsu T. A novel strategy for the negative selection in mouse embryonic stem cells operated with immunotoxin-mediated cell targeting. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:3653–3655. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.18.3653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cathomen T., and, Joung JK. Zinc-finger nucleases: the next generation emerges. Mol Ther. 2008;16:1200–1207. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lombardo A, Genovese P, Beausejour CM, Colleoni S, Lee YL, Kim KA.et al. (2007Gene editing in human stem cells using zinc finger nucleases and integrase-defective lentiviral vector delivery Nat Biotechnol 251298–1306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hockemeyer D, Soldner F, Beard C, Gao Q, Mitalipova M, DeKelver RC.et al. (2009Efficient targeting of expressed and silent genes in human ESCs and iPSCs using zinc-finger nucleases Nat Biotechnol 27851–857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou J, Maeder ML, Mali P, Pruett-Miller SM, Thibodeau-Beganny S, Chou BK.et al. (2009Gene targeting of a disease-related gene in human induced pluripotent stem and embryonic stem cells Cell Stem Cell 597–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruby KM., and, Zheng B. Gene targeting in a HUES line of human embryonic stem cells via electroporation. Stem Cells. 2009;27:1496–1506. doi: 10.1002/stem.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porteus MH., and, Carroll D. Gene targeting using zinc finger nucleases. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23:967–973. doi: 10.1038/nbt1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JC, Tan S, Qiao G, Barlow KA, Wang J, Xia DF.et al. (2011A TALE nuclease architecture for efficient genome editing Nat Biotechnol 29143–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaffer DV, Koerber JT., and, Lim KI. Molecular engineering of viral gene delivery vehicles. Annu Rev Biomed Eng. 2008;10:169–194. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.10.061807.160514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maguire AM, High KA, Auricchio A, Wright JF, Pierce EA, Testa F.et al. (2009Age-dependent effects of RPE65 gene therapy for Leber's congenital amaurosis: a phase 1 dose-escalation trial Lancet 3741597–1605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cideciyan AV, Hauswirth WW, Aleman TS, Kaushal S, Schwartz SB, Boye SL.et al. (2009Human RPE65 gene therapy for Leber congenital amaurosis: persistence of early visual improvements and safety at 1 year Hum Gene Ther 20999–1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasileva A, Linden RM., and, Jessberger R. Homologous recombination is required for AAV-mediated gene targeting. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:3345–3360. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang JH, Koerber JT, Kim JS, Asuri P, Vazin T, Bartel M.et al. (2011An evolved adeno-associated viral variant enhances gene delivery and gene targeting in neural stem cells Mol Ther 19667–675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith-Arica JR, Thomson AJ, Ansell R, Chiorini J, Davidson B., and, McWhir J. Infection efficiency of human and mouse embryonic stem cells using adenoviral and adeno-associated viral vectors. Cloning Stem Cells. 2003;5:51–62. doi: 10.1089/153623003321512166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maheshri N, Koerber JT, Kaspar BK., and, Schaffer DV. Directed evolution of adeno-associated virus yields enhanced gene delivery vectors. Nat Biotechnol. 2006;24:198–204. doi: 10.1038/nbt1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koerber JT, Jang JH., and, Schaffer DV. DNA shuffling of adeno-associated virus yields functionally diverse viral progeny. Mol Ther. 2008;16:1703–1709. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koerber JT, Klimczak R, Jang JH, Dalkara D, Flannery JG., and, Schaffer DV. Molecular evolution of adeno-associated virus for enhanced glial gene delivery. Mol Ther. 2009;17:2088–2095. doi: 10.1038/mt.2009.184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klimczak RR, Koerber JT, Dalkara D, Flannery JG., and, Schaffer DV. A novel adeno-associated viral variant for efficient and selective intravitreal transduction of rat Müller cells. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e7467. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Excoffon KJ, Koerber JT, Dickey DD, Murtha M, Keshavjee S, Kaspar BK.et al. (2009Directed evolution of adeno-associated virus to an infectious respiratory virus Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1063865–3870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W, Zhang L, Johnson JS, Zhijian W, Grieger JC, Ping-Jie X.et al. (2009Generation of novel AAV variants by directed evolution for improved CFTR delivery to human ciliated airway epithelium Mol Ther 172067–2077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimm D, Lee JS, Wang L, Desai T, Akache B, Storm TA.et al. (2008In vitro and in vivo gene therapy vector evolution via multispecies interbreeding and retargeting of adeno-associated viruses J Virol 825887–5911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Z, Asokan A., and, Samulski RJ. Adeno-associated virus serotypes: vector toolkit for human gene therapy. Mol Ther. 2006;14:316–327. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2006.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitsui K, Suzuki K, Aizawa E, Kawase E, Suemori H, Nakatsuji N.et al. (2009Gene targeting in human pluripotent stem cells with adeno-associated virus vectors Biochem Biophys Res Commun 388711–717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan IF, Hirata RK, Wang P-R, Li Y, Kho J, Nelson A.et al. (2010Engineering of human pluripotent stem cells by AAV-mediated gene targeting Mol Ther 181192–1199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller OJ, Kaul F, Weitzman MD, Pasqualini R, Arap W, Kleinschmidt JA.et al. (2003Random peptide libraries displayed on adeno-associated virus to select for targeted gene therapy vectors Nat Biotechnol 211040–1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park IH, Zhao R, West JA, Yabuuchi A, Huo H, Ince TA.et al. (2008Reprogramming of human somatic cells to pluripotency with defined factors Nature 451141–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kern A, Schmidt K, Leder C, Müller OJ, Wobus CE, Bettinger K.et al. (2003Identification of a heparin-binding motif on adeno-associated virus type 2 capsids J Virol 7711072–11081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Summerford C., and, Samulski RJ. Membrane-associated heparan sulfate proteoglycan is a receptor for adeno-associated virus type 2 virions. J Virol. 1998;72:1438–1445. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.2.1438-1445.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller DG, Petek LM., and, Russell DW. Human gene targeting by adeno-associated virus vectors is enhanced by DNA double-strand breaks. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:3550–3557. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.10.3550-3557.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pruett-Miller SM, Connelly JP, Maeder ML, Joung JK., and, Porteus MH. Comparison of zinc finger nucleases for use in gene targeting in mammalian cells. Mol Ther. 2008;16:707–717. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porteus MH, Cathomen T, Weitzman MD., and, Baltimore D. Efficient gene targeting mediated by adeno-associated virus and DNA double-strand breaks. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:3558–3565. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.10.3558-3565.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan IF, Hirata RK., and, Russell DW. AAV-mediated gene targeting methods for human cells. Nat Protoc. 2011;6:482–501. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2011.301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opie SR, Warrington KH, Jr, Agbandje-McKenna M, Zolotukhin S., and, Muzyczka N. Identification of amino acid residues in the capsid proteins of adeno-associated virus type 2 that contribute to heparan sulfate proteoglycan binding. J Virol. 2003;77:6995–7006. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.12.6995-7006.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy HC, Bowman VD, Govindasamy L, McKenna R, Nash K, Warrington K.et al. (2009Heparin binding induces conformation changes in adeno-associated virus serotype 2 J Struct Biol 165146–156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcaida MJ, Muñoz IG, Blanco FJ, Prieto J., and, Montoya G. Homing endonucleases: from basics to therapeutic applications. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2010;67:727–748. doi: 10.1007/s00018-009-0188-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson RS, Sheng M, Greenberg ME, Kolodner RD, Papaioannou VE., and, Spiegelman BM. Targeting of nonexpressed genes in embryonic stem cells via homologous recombination. Science. 1989;245:1234–1236. doi: 10.1126/science.2506639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schröder AR, Shinn P, Chen H, Berry C, Ecker JR., and, Bushman F. HIV-1 integration in the human genome favors active genes and local hotspots. Cell. 2002;110:521–529. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00864-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell DW., and, Hirata RK. Human gene targeting favors insertions over deletions. Hum Gene Ther. 2008;19:907–914. doi: 10.1089/hum.2008.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasty P, Crist M, Grompe M., and, Bradley A. Efficiency of insertion versus replacement vector targeting varies at different chromosomal loci. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:8385–8390. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.12.8385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta A, Meng X, Zhu LJ, Lawson ND., and, Wolfe SA. Zinc finger protein-dependent and -independent contributions to the in vivo off-target activity of zinc finger nucleases. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:381–392. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petek LM, Russell DW., and, Miller DG. Frequent endonuclease cleavage at off-target locations in vivo. Mol Ther. 2010;18:983–986. doi: 10.1038/mt.2010.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu JH., and, Schaffer DV. Selection of novel vesicular stomatitis virus glycoprotein variants from a peptide insertion library for enhanced purification of retroviral and lentiviral vectors. J Virol. 2006;80:3285–3292. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.7.3285-3292.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Q, Bu W, Bhatia S, Hare J, Somasundaram T, Azzi A.et al. (2002The atomic structure of adeno-associated virus (AAV-2), a vector for human gene therapy Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 9910405–10410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

AAV1.9 increases the number of donor molecules per cell.

AAV2-mediated correction of a nonfunctional GFP expressed in HEK293Ts and NT2s.

Representative analysis of residual AAV1.9 genomes.