Abstract

To better understand the nature of the relationships between mineral phases at the dentino–enamel boundary (DEB), we performed electron tomography (ET) and high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HR-TEM) of the apical portions of rat incisors. The ET studies of the DEB at the secretory stage of amelogenesis revealed that nascent enamel crystals are co-aligned and closely associated with dentin crystallites in the mineralized von Korff fibers, with the distances between dentin and enamel crystals in the nanometer range. We have further studied the relationships between dentin and enamel crystals using HR-TEM lattice imaging of the DEB. Among dozens of high-resolution micrographs taken from the DEB we were able to identify only one case of lattice continuity between dentin and enamel crystals, indicating direct epitaxy. In other cases, although there was no direct continuity between the crystalline lattices, power spectra analysis of lattice images revealed a very high level of co-alignment between dentin and enamel crystals. Hence, we propose here that the high degree of alignment and integration between dentin and enamel mineral can be established either by epitaxy or without direct interactions between crystalline lattices, probably via regulation of mineral formation and organization by integrated organic matrices of dentin and enamel at the DEB.

Keywords: dentino–-enamel boundary, electron tomography, high-resolution electron microscope, epitaxial growth

Dentin and enamel, two major dental tissues with extremely different structural and mechanical properties, normally perform together for tens of years without delamination or catastrophic failure (1, 2). This unique mechanical robustness of a tooth crown is determined largely by a complex interface structure called the dentino–enamel junction (DEJ) (3, 4). Although functional DEJ, according to some reports, is tens of microns thick (4), dentin and enamel are joined at an extremely robust interface that is only a few micrometers wide (5), called, in this study, the dentino–enamel boundary (DEB), to avoid confusion with the much wider DEJ. The extraordinary robustness of the DEB is believed to lie in the structural relationships of dentin and enamel at the atomic and molecular levels and to involve both organic and inorganic phases, although the exact nature of these interactions remains unclear.

Dentin is a member of the bone family of materials (6, 7). It contains approximately 20 weight % (wt%) organic matrix, approximately 70 wt% carbonated apatite mineral, and approximately 10% water. The major organic constituent of dentin is collagen type I, comprising approximately 90% of the dentin organic matrix, and non-collagenous proteins play important roles in the regulation of biomineralization and mechanical performance of the dentin tissues (6). The mineralized collagen fibril is the basic building block of dentin, in which plate-like crystallites, approximately 3 nm thick, organize into parallel arrays with their c-axes aligned along the fibril axis. In the dentin layer adjacent to enamel, the so-called mantle dentin, mineralized collagen fibrils, known as von Korff fibrils, are oriented normal to the DEB plane (8). In contrast to dentin, mature enamel comprises 95 wt% carbonated apatite and <1% organic matrix. Mature enamel crystals are about 50 nm wide and tens of microns long, with their c-axes oriented along the long axis of the crystal. Enamel crystals are organized into 4- to 5-μm-wide parallel arrays, called enamel rods, which form an intricate interwoven pattern. Yet, in the aprizmatic layer at the DEB, crystals do not form rods but are arranged into a palisade structure, a few microns thick, with their c-axes oriented normal to the DEB plane. Hence, the dentin and enamel crystals are co-aligned at the DEB. Enamel deposition starts at the DEB, on top of mineralized mantle dentin (9, 10), and is believed to be triggered by dentin mineralization. The initial mineral particles of enamel are approximately 2 nm thick, and ribbons of approximately 20 nm wide are embedded in the self-assembled protein gel (11). These mineral particles are organized into a pattern that is identical to the mature enamel structure and once the full thickness of enamel is achieved, the enamel matrix undergoes proteolytic degradation, accompanied by thickening of initial enamel crystals, leading to the formation of mature enamel (12).

In order to understand how the DEB works and to gain insights into the unique robustness and resilience of this interface, one needs to understand the relationships between the mineral phases of dentin and enamel. Specifically, it is important to understand how the formation and organization of mineral is regulated during the formation of the DEB. A number of studies addressing this question have been conducted over the years. One hypothesis that has emerged from these studies is that there are epitaxial relationships between dentin and enamel crystals. It was first suggested by Arsenault & Robinson (9), based on their observations of intimate relationships between dentin and enamel mineral at the DEB, that enamel crystals are ‘epitaxially induced’ by dental crystals. At the same time these authors emphasized the role of interactions between dentin and enamel organic matrices in establishing the continuity between dentin and enamel mineral. Using high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HR-TEM), Hayashi (13) observed lattice continuity between dentin and enamel crystals. At the same time, several papers have reported a lack of direct epitaxial relationships between dentin and enamel. Diekwisch et al. (14) found no direct relationships between dentin and enamel mineral. Similarly, Bodier-Houlle et al. (10), using HR-TEM and lattice imaging, observed that dentin and enamel crystals are separated by amorphous areas. These conflicting reports might be a result of differences in sample preparation and the characterization methodology and equipment. Nevertheless, the question of interactions between dentin and enamel crystals remains unresolved and requires additional investigations.

To gain a better understanding of the nature of the relationships between mineral phases at the DEB, we performed electron tomography (ET) and HR-TEM of resin-embedded sections of apical portions of rat incisors.

Material and methods

Mandibular incisors were collected from 8-wk-old Wistar rats. The animals were killed, according to a protocol approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, and the hemimandibles were dissected and immediately immersed in 4 mM PBS saturated in respect to hydroxyapatite. The incisors were carefully separated from the surrounding bone under a dissecting microscope using microsurgical tools. The apical immature portions of the incisors were then dissected from the rest of the tooth, flash-frozen in liquid ethane, and lyophilized. The lyophilized samples were perfused in a cold room at 4°C, embedded in LR White embedding medium (London Resin Company, Reading, UK) on ice, and left in the cold room for 24 h to polymerize. The samples were sectioned onto water saturated in respect to hydroxyapatite using a diamond knife and a Reichert Ultracut ultramicrotome, and then transferred onto #300 mesh Cu grids.

Electron tomography studies of thin sections of the DEB at the secretory stage of enamel formation were performed using a Tecnai 12 transmission electron microscope (FEI, Hillsboro, OR, USA), equipped with an LaB6 filament, at 120 kV. Tomography tilt series of thin-sectioned samples were acquired at nominal magnifications of ×23,000 to ×26,000. The micrographs were recorded automatically using a bottom-mounted Gatan 2000 charge-coupled device (CCD) camera (Gatan, Warrendale, PA, USA). The micrographs were taken in a tilt range from –60° to 60°, with a 1° increment from –45° to 45°, and a 0.5° increment from –60° to –45° and from 45° to 60°. Because of the strong contrast of mineralized samples, the images were aligned using fiducial-less procedure in the IMOD 3.9 reconstruction package (University of Colorado, Boulder, CO, USA). Three-dimensional density maps were reconstructed from the tilt-series images using Chimera software (University of California, San Francisco, CA, USA).

HR-TEM of the DEB was performed using a Tecnai F20 (FEI) microscope equipped with a field-emission gun at 200-kV accelerating voltage. The images were recorded using a Gatan 4k × 4k CCD camera. The power spectra of the lattice images of mineral crystals at the DEB were created and analyzed using imagej 1.44 image-processing software (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA).

Results

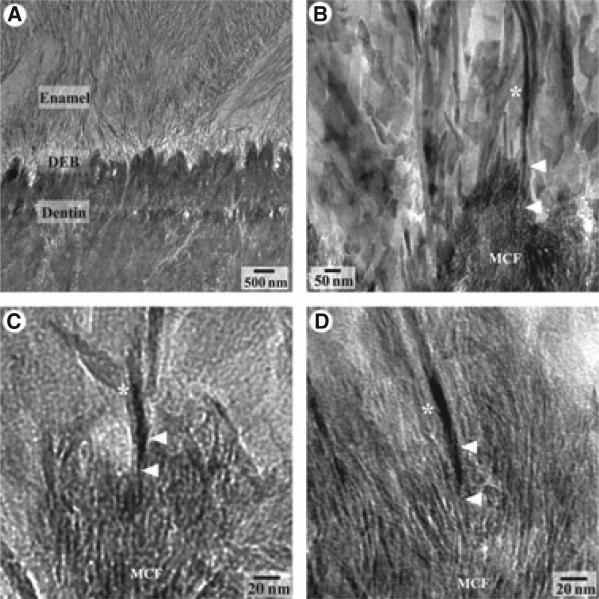

The TEM image of the DEB at the secretory stage revealed that the von Korff fibrils of mantle dentin were intimately associated with enamel mineral particles (Fig. 1A). The mineral crystallites in the mineralized von Korff fibrils, as well as the ribbon-like 10- to 20-nm-thick enamel mineral particles in the aprismatic enamel layer were found to be oriented normal to the DEB plane, indicating the continuity of the crystal orientation between dentin and enamel. Higher-magnification micrographs showed that the enamel crystals directly interface with dentin crystallites, and many of them are ‘embedded’ into the mineralized von Korff fibrils (Fig. 1B–D).

Fig. 1.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) micrographs of the dentino–enamel boundary (DEB) in non-demineralized sections of the midsecretory stage of enamel formation at low magnification (A) and high magnifications (B–D). Note that the dentin and enamel mineral are tightly integrated at the DEB. Arrowheads point to the adjacent dentin crystallites in the mineralized von Korff fibrils and enamel crystals (*).

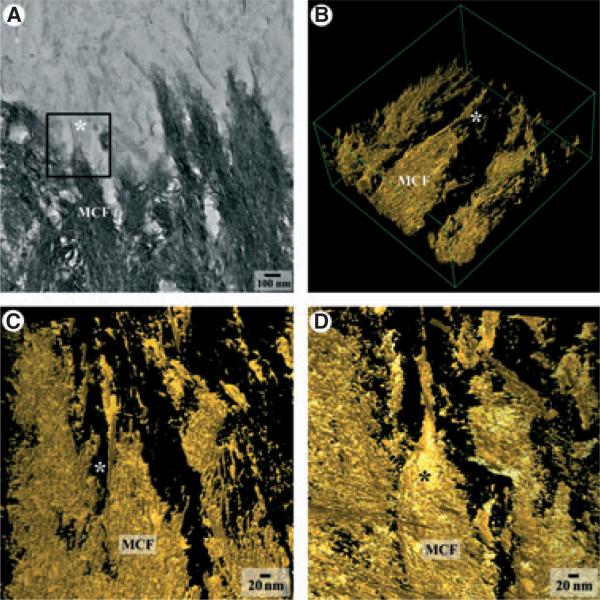

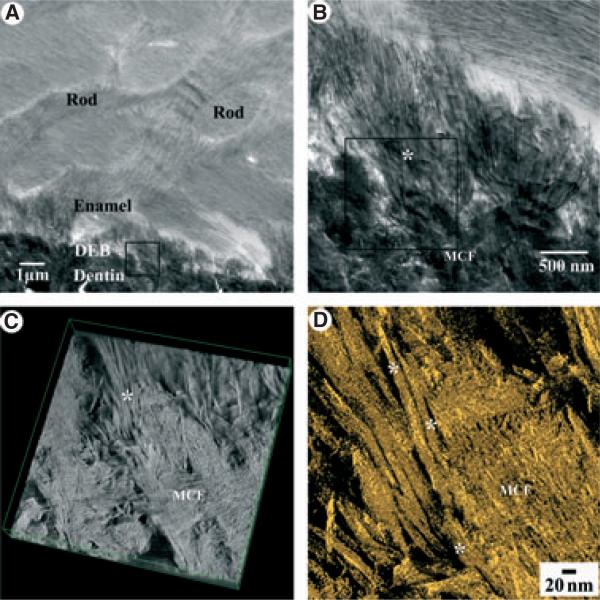

To gain a better understanding of the relationships between the mineralized collagen fibrils in mantle dentin and the mineral particles of secretory enamel, we carried out a series of ET studies of areas of the DEB, located at different distances from the cervical loop. In the region of initial enamel mineral deposition we observed a number of enamel mineral particles intimately attached to the mineralized von Korff fibrils (Fig. 2, Video S1). The three-dimensional (3D) reconstruction of the area shown in Fig. 2A revealed a long ribbon-like enamel mineral particle that was closely associated with a mineralized collagen fibril (Fig. 2B,C) and with the mineral crystals within the fibril, and that its long axis was co-aligned with the crystallites in the fibril (Fig. 2, Video S1). Figure 3 and Video S2 represent a tomographic reconstruction of the area of the DEB at the late secretory/transitional phase of enamel formation. At this stage the enamel crystals are much more numerous; however, they are similarly intertwined with the crystallites of the mineralized collagen fibrils of mantle dentin. Overall, the tomography studies indicate that the enamel mineral at the DEB is integrated into the mineralized von Korff fibrils and exists in very close physical contact with dentin crystallites at the nanoscale level.

Fig. 2.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) tomographic reconstruction of an enamel crystal (*) associated with the mineralized von Korff fibril at the dentino–enamel boundary (DEB) of early secretory-stage enamel. (A) Intermediate-resolution TEM micrograph taken from the region of the DEB that was subjected to the tomographic reconstruction; the black square represents the area of the reconstruction. (B) Isometric projection of the reconstructed volume, and views of the reconstructed volume at –40° (C) and 40° (D).

Fig. 3.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) tomographic reconstruction of enamel crystal (*) bundles integrated into mineralized collagen fibrils of mantle dentin at the late secretory/transition phase of enamel formation. Low-magnification (A) and high-magnification (B) views. The black square in B outlines the area from which the tomographic reconstruction was taken. (C) Isometric projection of the reconstructed volume, and a view of the reconstructed volume at –20° (D).

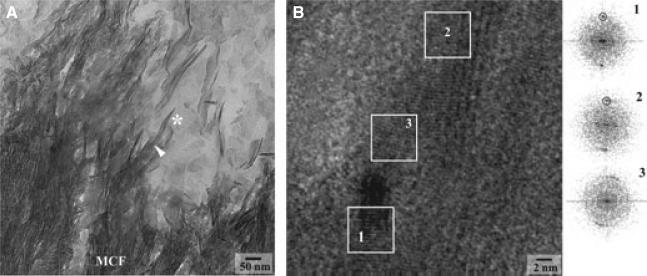

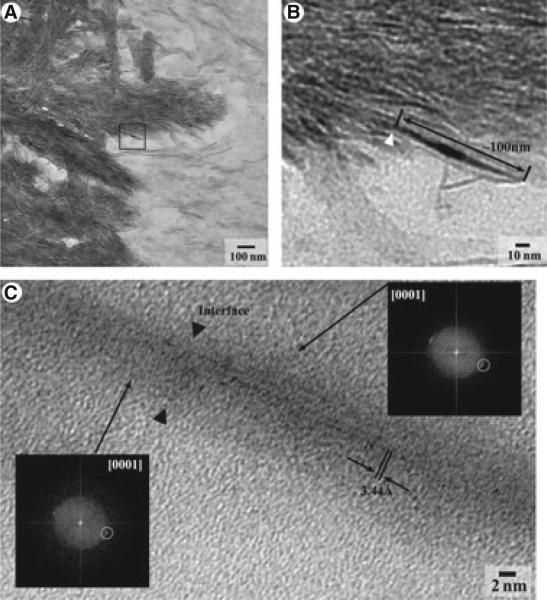

To investigate the relationships between dentin and enamel crystals at the atomic scale we conducted an extensive HR-TEM study of the DEB. We took several dozen HR-TEM images from different locations of the DEB and performed lattice image analysis of the micrographs. Although the analysis of the power spectra of dentin and enamel crystals revealed a very high level of crystallographic alignment in many areas (Fig. 4), we found only one area in which we could clearly observe lattice continuity between dentin and enamel crystals (Fig. 5). In this location an enamel crystal was embedded into a mineralized collagen fibril at the DEB (Fig. 5A). A close examination revealed that this enamel crystal, approximately 10 nm thick, is intimately associated with a much thinner dentin crystal (Fig. 5B). The lattice image analysis of both crystals revealed a continuing crystalline lattice spanning both crystals with the spacing of 4.7 Å, characteristic of [001] zone axis of biologic apatites (15, 16).

Fig. 4.

(A) Intermediate-magnification transmission electron microscopy (TEM) micrograph of the dentino–enamel boundary (DEB) and (B) high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HR-TEM) of the area marked by the arrowhead in (A) where enamel crystal (*) interfaces with crystallites of mineralized von Korff fibril of dentin. The insets in (B) represent power spectra taken from the boxed areas of the micrograph with the corresponding numbers: 1 is a dentin crystallite, 2 is an enamel crystal, and 3 is a poorly crystalline zone separating crystals 1 and 2. Both crystals are well co-aligned, yet there is no continuity between these two lattices. (The circled spots in the power spectra correspond to 001 lattices.)

Fig. 5.

Intermediate-magnification (A) and high-magnification (B) transmission electron microscopy (TEM) micrographs of the dentino–enamel boundary (DEB), and (C) high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HR-TEM) of an interface between dentin and an enamel crystal indicated by an arrow-head in (B). The black arrow heads represent the interface between dentin and an enamel crystal (C); two power spectra from the areas of the dentin and enamel crystals indicated by the arrows are in the insets. Both crystals are ideally co-aligned, based on the identical positions of the 001 reflections in the power spectra (circled spots).

Discussion

The results of our ET study demonstrate that the enamel crystals at the DEB are intertwined in the mineralized von Korff fibrils and these intimate interactions between dentin and enamel mineral can be observed very early at the onset of enamel deposition. These results further demonstrate that the dentin crystallites in the von Korff fibrils are co-aligned and closely associated at the nanoscale level with enamel mineral ribbons at the DEB. These results support the view first articulated by Arsenault & Robinson (9), that initial enamel forms directly on the mineralized mantle dentin and that enamel and dentin mineral are interconnected.

Our lattice analysis of the dentin and enamel crystals at the DEB revealed at least one instance of true epitaxial relationships between dentin and enamel crystals. The fact that we were able to identify only one instance of lattice continuity between dentin and enamel crystals might be a result of the combination of a complicated nature of the sample and rare conditions in which the lattice continuity can be observed. Specifically, the crystals of interest have to be uniquely aligned in respect to the section plane and not obscured by other crystals. Nevertheless, our observation supports earlier reports of epitaxial relationships at this interface (17). The observation of lattice continuity between dentin and enamel crystals is quite interesting in light of our recent discovery that the initial mineral phase in forming enamel is amorphous calcium phosphate (ACP) (18). We have shown that the initial mineral particles of enamel are amorphous and they subsequently transform into apatitic crystals. Interestingly, the shape determination and organization of enamel mineral particles into bundles occurs before they crystallize. In light of these data it is not clear how the lattice continuity is achieved between dentin and enamel crystals at the DEB. One possible scenario is that alignment of dentin and enamel crystals occurs after the crystallization takes place, as previously described in other systems, where small crystallites can re-align their lattices via a so-called aggregation-based crystal growth mechanism (19, 20). Additional studies are needed to clarify this interesting point.

Intriguingly, in many areas of the DEB we did not observe continuity between dentin and enamel crystal lattices. At the same time the analysis of the power spectra obtained from these areas revealed a very good crystallographic alignment between dentin and enamel crystals. One possible explanation of this paradox is that the elements of dentin and enamel matrices at the DEB interact and become arranged into supramolecular complexes that guide growth and organization of mineral particles in a manner that ensures structural continuity at the interface. Such a scenario was first proposed by Arsenault & Robinson (9) and was later supported by the HR-TEM study of Bodier-Houlle et al. (10). We have recently conducted an in vitro mineralization study in the presence of collagen fibrils and the major enamel protein amelogenin (21). We found that amelogenin interacts with collagen fibrils and self-organizes on their surfaces. Furthermore, these in vitro experiments demonstrate that the interactions between collagen and amelogenin matrices lead to the formation of highly organized mineralized structures resembling the interface between dentin and enamel mineral at the DEB. It has been reported that other extracellular proteins of dentin and enamel, such as dentin matrix acidic phosphoprotein 1 (DMP1) and enamelin, are present at higher concentrations at the DEB (22, 23), which suggests that they may be involved in mineral formation and structural organization at this interface. Overall, these results further support the notion that the organic matrix assemblies can play a major role in establishing the integration of dentin and enamel mineral.

In conclusion, our results demonstrate that enamel mineral particles at the DEB are tightly integrated with the mineralized von Korff fibrils of mantle dentin. This integration was observed throughout the secretory stage of enamel formation starting with the initial mineral deposits. We found one instance of lattice continuity between dentin and enamel crystals, indicating possible epitaxial interactions. At the same time, no clear lattice continuity was observed in other areas, even though the crystals were extremely well aligned, suggesting that the organic matrix might play a role in maintaining the continuity between dentin and enamel crystals at the DEB.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article:

Video S1. Tomographic reconstruction of the DEB at the early secretory phase of enamal formation.

Video S2. Tomograph reconstruction of the DEB at the late secretory/transitional phase of enamel formation.

Please note: Wiley-Blackwell are not responsible for the content or functionality of any supporting materials supplied by the authors. Any queries (other than missing material) should be directed to the corresponding author for the article.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIDCR grant R01-DE016703 (E.B.). We thank Dr James Conway and Dr Peijun Zhang from the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Department of Structural Biology, for allowing us access to the TEM facilities.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest – The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Chai H, Lee JJW, Constantino PJ, Lucas PW, Lawn BR. Remarkable resilience of teeth. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:7289–7293. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902466106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lawn BR, Lee JJW, Chai H. Teeth: among nature's most durable biocomposites. Annu Rev Mater Res. 2009;40:55–75. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Imbeni V, Kruzic JJ, Marshall GW, Marshall SJ, Ritchie RO. The dentin-enamel junction and the fracture of human teeth. Nat Mater. 2005;4:229–232. doi: 10.1038/nmat1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zaslansky P, Friesem AA, Weiner S. Structure and mechanical properties of the soft zone separating bulk dentin and enamel in crowns of human teeth: insight into tooth function. J Struct Biol. 2006;153:188–199. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2005.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Habelitz S, Marshall SJ, Marshall GW, Jr, Balooch M. The functional width of the dentino-enamel junction determined by AFM-based nanoscratching. J Struct Biol. 2001;135:294–301. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.2001.4409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beniash E. Biominerals—hierarchical nanocomposites: the example of bone. Wiley Interdiscip Rev: Nanomed Nanobiotechnol. 2011;3:47–69. doi: 10.1002/wnan.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weiner S, Wagner HD. The material bone: structure mechanical function relations. Annu Rev Mater Sci. 1998;28:271–298. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nanci A. Ten cate's oral histology: development, structure, and function. Mosby; St. Louis: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arsenault AL, Robinson BW. The dentino-enamel junction – a structural and microanalytical study of early mineralization. Calcif Tissue Int. 1989;45:111–121. doi: 10.1007/BF02561410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bodier-Houlle P, Steuer P, Meyer JM, Bigeard L, Cuisinier FJG. High-resolution electron-microscopic study of the relationship between human enamel and dentin crystals at the dentinoenamel junction. Cell Tissue Res. 2000;301:389–395. doi: 10.1007/s004410000241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Margolis HC, Beniash E, Fowler CE. Role of macromolecular assembly of enamel matrix proteins in enamel formation. J Dent Res. 2006;85:775–793. doi: 10.1177/154405910608500902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Simmer JP, Hu JCC. Expression, structure, and function of enamel proteinases. Connect Tissue Res. 2002;43:441–449. doi: 10.1080/03008200290001159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hayashi Y. High-resolution electron-microscopy in the dentinoenamel junction. J Electron Microsc. 1992;41:387–391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Diekwisch TGH, Berman BJ, Gentner S, Slavkin HC. Initial enamel crystals are not spatially associated with mineralized dentin. Cell Tissue Res. 1995;279:149–167. doi: 10.1007/BF00300701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cuisinier F, Bres EF, Hemmerle J, Voegel JC, Frank RM. Transmission electron-microscopy of lattice planes in human alveolar bone apatite crystals. Calcif Tissue Int. 1987;40:332–338. doi: 10.1007/BF02556695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cuisinier FJG, Steuer P, Senger B, Voegel JC, Frank RM. Human amelogenesis. 1. High-resolution electron-microscopy study of ribbon-like crystals. Calcif Tissue Int. 1992;51:259–268. doi: 10.1007/BF00334485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tohda H, Yamada M, Yamaguchi Y, Yanagisawa T. High-resolution electron microscopical observations of initial enamel crystals. J Electron Microsc. 1997;46:97–101. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beniash E, Metzler RA, Lam RSK, Gilbert PUPA. Transient amorphous calcium phosphate in forming enamel. J Struct Biol. 2009;166:133–143. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2009.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Banfield JF, Welch SA, Zhang HZ, Ebert TT, Penn RL. Aggregation-based crystal growth and microstructure development in natural iron oxyhydroxide biomineralization products. Science. 2000;289:751–754. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5480.751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pacholski C, Kornowski A, Weller H. Self-assembly of ZnO: from nanodots to nanorods. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2002;41:1188–1191. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020402)41:7<1188::aid-anie1188>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Deshpande AS, Fang P-A, Simmer JP, Margolis HC, Beniash E. Amelogenin-collagen interactions regulate calcium phosphate mineralization in vitro. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:19277–19287. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.079939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Beniash E, Deshpande AS, Fang PA, Lieb NS, Zhang X, Sfeir CS. Possible role of DMP1 in dentin mineralization. J Struct Biol. 2011;174:100–106. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2010.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dohi N, Murakami C, Tanabe T, Yamakoshi Y, Fukae M, Yamamoto Y, Wakida K, Shimizu M, Simmer JP, Kurihara H, Uchida T. Immunocytochemical and immunochemical study of enamelins, using antibodies against porcine 89-kDa enamelin and its N-terminal synthetic peptide, in porcine tooth germs. Cell Tissue Res. 1998;293:313–325. doi: 10.1007/s004410051123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting Information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article:

Video S1. Tomographic reconstruction of the DEB at the early secretory phase of enamal formation.

Video S2. Tomograph reconstruction of the DEB at the late secretory/transitional phase of enamel formation.

Please note: Wiley-Blackwell are not responsible for the content or functionality of any supporting materials supplied by the authors. Any queries (other than missing material) should be directed to the corresponding author for the article.