The ability to track the temporal structure of events in a dynamic environment is crucial to cognition and action alike. In order to guide timely reactive and proactive behavior the individual has to draw upon some internal representation of temporal relations or temporal structure. Here an event may be defined as a perceived change in the formal structure of the environment, i.e., the identity (“what”) or the position (“where”) of an object. In turn, the temporal relation between events may be defined as the temporal structure (“when”) of the environment.

Temporal structure develops on different timescales (Buonomano, 2007). For example, starting and stopping to walk from one position to another marks events with a certain temporal relation, typically in the seconds-to-minutes range. Yet, contact of a foot with the surface establishes another kind of event, with successive steps marking temporal structure in the milliseconds range. Such marking of the beginning and the end of an action sequence is represented in prefrontal and supplementary motor cortices (Fujii and Graybiel, 2003; Shima and Tanji, 2006). However, the question arises as to whether the perception and production of the corresponding temporal structure in the milliseconds-to-seconds range is intrinsic or whether it is based on an explicit representation generated by a dedicated temporal processing system (Karmarkar and Buonomano, 2007; Ivry and Schlerf, 2008; Spencer et al., 2009). Compelling evidence suggests that temporal processing, i.e., the neural mechanisms that engage in encoding, decoding, and evaluating of temporal structure, relies on brain regions involved in action control: the cerebellum, the basal ganglia, and the supplementary motor area (SMA; for a review see Coull et al., 2011).

However, a high-level function such as action control incorporates various lower-level processes. This becomes apparent if one considers the role of the SMA in action control. Located bilaterally in Brodmann area 6 of the medial frontal lobe, the SMA has traditionally been linked to the planning and the preparation of future, sequential, and rhythmic performance, as well as to the initiation, inhibition, preservation, and repetition of action (Brickner, 1939; Penfield, 1950; Goldberg, 1985; Tanji, 1996). Crucially, SMA lesions affect non-verbal and verbal behavior. They may result in the inability to speak, stuttering, hesitations, “slowliness,” the prolonging of sounds, and persistent dysfluency, phenomena, which impact the continuous flow or pacing, i.e., the rate and rhythm of speech (Jonas, 1981; Ziegler et al., 1997). These phenomena corroborate a role of the SMA in controlling temporal relations in action, but leave open whether temporal processing is intrinsic or explicitly dedicated. However, evidence for a dedicated temporal processing system comes from studies, which confirm a role of the SMA not only in the production, but also in the perception of temporal structure (Macar et al., 2002; Ferrandez et al., 2003; Coull et al., 2004).

The SMA, or more specifically, the SMA and its striato-thalamic connections, is a candidate neural substrate for a “temporal accumulator” engaged in the encoding of temporal structure (Akkal et al., 2004; Pouthas et al., 2005; Macar et al., 2006; Casini and Vidal, 2011). Furthermore, considering a structural differentiation of the SMA into a rostral pre-SMA and a more caudal SMA-proper (Picard and Strick, 2001), it has been suggested that pre-SMA is essential for attention-dependent quantification (Coull et al., 2004; Macar et al., 2004) or “tagging” of temporal structure (Pastor et al., 2006). Such functional specification based on structural differentiation may reflect an interaction within a distributed temporal processing network, which is determined by unique connections from the pre-SMA and the SMA-proper to other cortical and subcortical regions (Johansen-Berg et al., 2004; Akkal et al., 2007).

Among others, connections from the pre-SMA target the prefrontal cortex, while connections from the SMA-proper target motor and pre-motor cortices (Johansen-Berg et al., 2004). However, the thalamus connects both pre-SMA and SMA-proper to essential nodes within a dedicated temporal processing network, namely the cerebellum and the basal ganglia. Connections from both SMA subareas to the basal ganglia maintain a rostro-caudal gradient in their structural and functional organization and establish a cortico-striato-thalamo-cortical looped system (Johansen-Berg et al., 2004; Draganski et al., 2008). Connections between the pre-SMA and the cerebellum originate in the non-motor part of the cerebellar dentate nucleus, whereas connections to the SMA-proper originate in its motor part (Dum and Strick, 2003; Akkal et al., 2007).

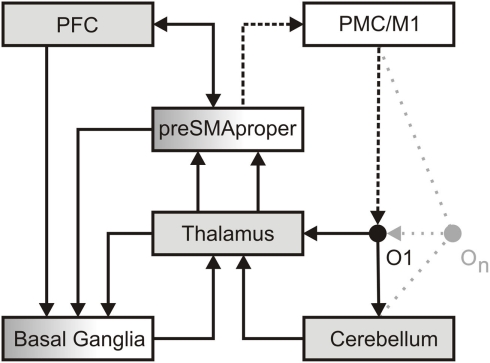

In general, the SMA receives more input from the basal ganglia than from the cerebellum (Akkal et al., 2007). Next to direct subcortico-subcortical connections (Hoshi et al., 2005; Bostan and Strick, 2010; Bostan et al., 2010), this structural embedding of the pre-SMA and the SMA-proper into subcortico-thalamo-cortical processing streams instantiates interaction between the cerebellum and the basal ganglia in temporal processing (Schwartze et al., in press). Note, that the role of the thalamus as a mere relay station is therefore simply underspecified (see Sherman, 2007). Rather, the thalamus should be considered a key structure in modeling the neural basis of temporal processing. Thalamic neurons convey information to cortical targets in either a tonic or a burst firing mode (Sherman and Guillery, 2002). The tonic firing mode preserves input linearity, whereas the burst firing mode affords better input detectability. The burst firing mode is thus ideally suited to signal changes in the environment to cortical targets by means of stronger cortical excitation (Sherman, 2001). These firing mode characteristics not only support the linking of several nodes, but also allow speculating about their impact on functional interactions within such a dedicated temporal processing network (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

A dedicated temporal processing network. In perception, detailed information regarding the formal structure of an object (O1) reaches the thalamus. This information is then transmitted in a linear, faithful fashion by means of thalamic tonic and burst firing (Sherman, 2001) to sensory cortices (not in view) in order to establish as well as to access a memory representation of an object. In parallel, less detailed information reaches the cerebellum. Here a salient change in the formal structure of an object is encoded as an event. A sequence of objects (On) may give rise to a precise event-based representation of temporal structure. Such event-based representation implicitly encodes the temporal relation between events. Potentially amplified via thalamic burst firing, events may provide attractors to adaptive cortical oscillations implicated in dynamic attending. Attention oscillations may generate an “expectancy scheme” via entrainment to different hierarchical levels of temporal structure (Large and Jones, 1999; Drake et al., 2000). Alternatively or additionally, events may activate ensembles of non-adaptive cortical oscillations, which, according to the influential striatal-beat-frequency model, provide a unique pattern of input to the basal ganglia (Matell and Meck, 2004). These oscillations serve interval-based temporal processing and, by additional recruitment of working memory, the subsequent evaluation of temporal structure. Both kinds of oscillations may reflect the combined effort of the pre-SMA and the prefrontal cortex (PFC), as well as the associated striato-thalamo-cortical loops to “tag” the temporal structure of the sequence. In production, the intention to act (PFC) draws upon the pre-SMA and its connections to the basal ganglia to initiate action and to define the temporal structure of a sequence of actions, i.e., the pre-SMA is recruited to temporally structure forthcoming motor behavior (Mita et al., 2009). The actual implementation of action (dotted line) recruits the SMA-proper and pre-motor/primary motor cortices (PMC/M1). Via its connections to the SMA-proper, the cerebellum may engage in the temporal fine-tuning of actions. In turn, each action constitutes an object in the environment. A sequence of actions (On) generates changes in the formal structure of the environment and establishes a sensorimotor processing cycle.

In this network pre-SMA and SMA-proper engage in different but related aspects of temporal processing. On the one hand, in perception the pre-SMA plays a pivotal role in the allocation of attention in time and in the encoding of temporal relations conveyed in a sequence of events. On the other hand, in production, the SMA-proper engages in the corresponding implementation of sequential action. Crucially, the SMA-proper integrates information regarding the temporal relation between successive actions provided by the pre-SMA and the basal ganglia. In other words, the function of the pre-SMA relates to the explicit encoding of temporal structure in perception and production, while the SMA-proper uses this information to implement a sequential action. This account of pre-SMA function is compatible with, and extends the dual role of the pre-SMA in the planning and the acquisition of movement patterns (Tanji, 1996). If, for example, changes in the environment require the adaptation of an action sequence (i.e., walking on uneven ground) such adaptation necessitates proactive and reactive adjustments – processes, which in turn benefit from a precise representation of temporal structure. Consequently, imprecise temporal processing may affect both cognitive and motor behavior. Hence, the proposed network has major implications for the modeling of basal ganglia dysfunctions (i.e., motor and cognitive) as exemplified in Parkinson's disease (PD).

Parkinson's disease is but one of several pathologies associated with impaired temporal processing (for a review see Allman and Meck, 2011). Early on PD has been linked to temporal processing deficits both in production and perception (Pastor et al., 1992; O'Boyle et al., 1996; Harrington et al., 1998). More recent data suggest that such deficits are rather diverse and may be more pronounced in the suprasecond than the subsecond range (Smith et al., 2007; Koch et al., 2008, but see Jahanshahi et al., 2006), and probably reflect different PD subgroups (Merchant et al., 2008). These studies allow drawing conclusions about the involvement of the basal ganglia in temporal processing based on the known neuropathology of PD. However, it is evident that the basal ganglia are not the only brain region that engages in temporal processing and is affected by PD. Combined activation of the basal ganglia and the SMA is a common observation in temporal processing (e.g., Ferrandez et al., 2003; Pouthas et al., 2005; Jahanshahi et al., 2006; Stevens et al., 2007). This emphasizes that the basal ganglia and the SMA contribute to the pathogenesis of PD. Thus, if the basal ganglia and SMA are considered as nodes within a dedicated temporal processing network spanning both perception and production, the question arises as to whether connections originating in, and targeting the SMA are at the core of impaired temporal processing in PD. However, PD is a progressive disease and different stages of the disease may be reflected in dynamic changes in the network. For example, a selective loss of pyramidal neurons in the pre-SMA in PD may cause underactivity in this region (MacDonald and Halliday, 2002), which, in turn, may result in erratic temporal processing. In contrast, stronger activation of the pre-SMA in action sequencing may reflect an early, preclinical compensation mechanism (Van Nuenen et al., 2009). Crucially, input from the cerebellum should influence this compensatory mechanism. Hyperactivation of cerebellar-pre-SMA connections as a consequence of internally cued actions during the early clinical stages of PD further supports this view (Wu and Hallett, 2005; Eckert et al., 2006; Lewis et al., 2007). However, hyperactivation is not necessarily limited to internally cued action. Rather, it may also reflect a stronger weighting toward cerebellar-SMA connections in externally cued action (i.e., finger-tapping: Sen et al., 2010). While this perspective is compatible with the proposed temporal processing network, i.e., a role of the cerebellum in transmitting the temporal structure of changes in the environment to the pre-SMA, such compensatory activity necessitates further differentiation of cerebellar function in the perception of temporal structure.

Functional connectivity indicates that during the perception of temporal structure the cerebellum projects to regions involved in perceptual orienting including the pre-SMA (Coull et al., 2004; O'Reilly et al., 2008). The functional interpretation of a larger network affected in PD is compatible with the notion of a dedicated and integrative temporal processing network (Kotz and Schwartze, 2010). Moreover, such a framework offers a suitable explanation for the effectiveness of intervention methods such as repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) that allow targeting the respective functional contribution of network areas in PD. It has been shown that rTMS affects motor planning in PD patients and controls differently (Cunnington et al., 1996). Koch et al. (2004) showed that rTMS over the SMA improved time perception, while Hamada et al. (2008) reported improved motor behavior after similar rTMS treatment over the SMA. The fact that different rTMS protocols (Koch, 2010) and stimulation of target network nodes (i.e., bilateral cerebellum and SMA) lead to either improvement or slight functional loss (Koch et al., 2005) clearly suggest further intra- and inter-hemispheric structural and functional differentiation within relevant network nodes.

We conclude that the perception and production of temporal relations is not merely a by-product of cognition and action, but that temporal structure provides information that is central to efficient behavior. Moreover, high precision in temporal processing benefits behavior as it allows generating precise predictions about upcoming events, a phenomenon that appears to be affected in PD. The current opinion summarizes previous evidence and synthesizes as well as accentuates a novel perspective on the structural and functional differentiation of the “SMA” in temporal processing and its relevance in a broader and integrative subcortico-thalamo-cortical dedicated temporal processing network.

References

- Akkal D., Dum R. P., Strick P. L. (2007). Supplementary motor area and presupplementary motor area: targets of basal ganglia and cerebellar output. J. Neurosci. 27, 10659–10673 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3134-07.2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akkal D., Escola L., Bioulac B., Burbaud P. (2004). Time predictability modulates pre-supplementary motor area neuronal activity. Neuroreport 15, 1283–1286 10.1097/01.wnr.0000127347.87552.87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allman M. J., Meck W. H. (2011). Pathophysiological distortions in time perception and timed performance. Brain 10.1093/brain/awr210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bostan A. C., Dum R. P., Strick P. L. (2010). The basal ganglia communicate with the cerebellum. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 8452–8456 10.1073/pnas.1000496107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bostan A. C., Strick P. L. (2010). The cerebellum and basal ganglia are interconnected. Neuropsychol. Rev. 20, 261–270 10.1007/s11065-010-9143-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brickner R. M. (1939). A human cortical area producing repetitive phenomena when stimulated. J Neurophysiol. 3, 128–130 [Google Scholar]

- Buonomano D. V. (2007). The biology of time across different scales. Nat. Chem. Biol. 3, 594–597 10.1038/nphys702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casini L., Vidal F. (2011). The SMAs: neural substrate of the temporal accumulator? Front. Integr. Neurosci. 5:35. 10.3389/fnint.2011.00035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coull J. T., Cheng R., Meck W. H. (2011). Neuroanatomical and neurochemical substrates of timing. Neuropsychopharmacology 36, 3–25 10.1038/npp.2010.113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coull J. T., Vidal F., Nazarian B., Macar F. (2004). Functional anatomy of the attentional modulation of time estimation. Science 303, 1506–1508 10.1126/science.1091573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunnington R., Iansek R., Thickbroom G. W., Laing B. A., Mastaglia F. L., Bradshaw J. L., Phillips J. G. (1996). Effects of magnetic stimulation over supplementary motor area on movement in Parkinson's disease. Brain 119, 815–822 10.1093/brain/119.3.815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Draganski B., Kherif F., Klöppel S., Cook P. A., Alexander D. C., Parker G. J. M., Deichmann R., Ashburner J., Frackowiak R. S. J. (2008). Evidence for segregated and integrativeconnectivity patterns in the basal ganglia. J. Neurosci. 28, 7143–7152 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1486-08.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake C., Jones M. R., Baruch C. (2000). The development of rhythmic attending in auditory sequences: attunement, referent period, focal attending. Cognition 77, 251–288 10.1016/S0010-0277(00)00106-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dum R. P., Strick P. L. (2003). An unfolded map of the cerebellar dentate nucleus and its projections to the cerebral cortex. J. Neurophysiol. 89, 634–639 10.1152/jn.00626.2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckert T., Peschel T., Heinze H., Rotte M. (2006). Increased pre-SMA activation in early PD patients during simple self-initiated hand movements. J. Neurol. 253, 199–207 10.1007/s00415-005-0956-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrandez A. M., Hugueville L., Lehéricy S., Poline J. B., Marsault C., Pouthas V. (2003). Basal ganglia and supplementary motor area subtend duration perception: an fMRI study. Neuroimage 19, 1532–1544 10.1016/S1053-8119(03)00159-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujii N., Graybiel A. M. (2003). Representation of action sequence boundaries by macaque prefrontal cortical neurons. Science 301, 1246–1249 10.1126/science.1086872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg G. (1985). Supplementary motor area structure and function: review and hypotheses. Behav. Brain Sci. 8, 567–616 10.1017/S0140525X00045325 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hamada M., Ugawa Y., Tsuji S. (2008). High-frequency rTMS over the supplementary motor area for treatment of Parkinson's disease. Mov. Disord. 23, 1524–1531 10.1002/mds.22168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrington D. L., Haaland K. Y., Hermanowicz N. (1998). Temporal processing in the basal ganglia. Neuropsychology 12, 3–12 10.1037/0894-4105.12.1.3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoshi E., Tremblay L., Féger J., Carras P. L., Strick P. L. (2005). The cerebellum communicates with the basal ganglia. Nat. Neurosci. 8, 1491–1493 10.1038/nn1544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivry R. B., Schlerf J. E. (2008). Dedicated and intrinsic models of time perception. Trends Cogn. Sci. (Regul. Ed.) 12, 273–280 10.1016/j.tics.2008.04.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahanshahi M., Jones C. R. G., Dirnberger G., Frith C. D. (2006). The substantia nigra pars compacta and temporal processing. J. Neurosci. 26, 12266–12273 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2540-06.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansen-Berg H., Behrens T. E. J., Robson M. D., Drobnjak I., Rushworth M. F. S., Brady J. M., Smith S. M., Higham D. J., Matthews P. M. (2004). Changes in connectivity profiles define functionally distinct regions in human medial frontal cortex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 13335–13340 10.1073/pnas.0403743101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonas S. (1981). The supplementary motor region and speech emission. J. Commun. Disord. 14, 349–373 10.1016/0021-9924(81)90019-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karmarkar U. R., Buonomano D. V. (2007). Timing in the absence of clocks: encoding time in neural network states. Neuron 53, 427–438 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.01.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch G. (2010). rTMS effects on levodopa induced dyskinesias in Parkinson's disease patients: searching for effective cortical targets. Restor. Neurol. Neurosci. 28, 561–568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch G., Brusa L., Caltagirone C., Peppe A., Oliveri M., Stanzione P., Centonze D. (2005). rTMS of supplementary motor area modulates therapy-induced dyskinesias in Parkinson disease. Neurology 65, 623–625 10.1212/01.wnl.0000172861.36430.95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch G., Costa A., Brusa L., Peppe A., Gatto I., Torriero S., Gerfo E. L., Salerno S., Oliveri M., Carlesimo G. A., Caltagirone C. (2008). Impaired reproduction of second but not millisecond time intervals in Parkinson's disease. Neuropsychologia 46, 1305–1313 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2007.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch G., Oliveri M., Brusa L., Stanzione P., Torriero S., Caltagirone C. (2004). High-frequency rTMS improves time perception in Parkinson's disease. Neurology 63, 2405–2406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotz S. A., Schwartze M. (2010). Cortical speech processing unplugged: a timely subcortico-cortical framework. Trends Cogn. Sci. (Regul. Ed.) 14, 392–399 10.1016/j.tics.2010.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Large E. W., Jones M. R. (1999). The dynamics of attending: how we track time-varying events. Psychol. Rev. 106, 119–159 10.1037/0033-295X.106.1.119 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis M. M., Slagle C. G., Smith A. B., Truong Y., Bai P., McKeown M. J., Mailman R. B., Belger A., Huang X. (2007). Task specific influences of Parkinson's disease on the striato-thalamo-cortical and cerebello-thalamo-cortical motor circuitries. Neuroscience 147, 224–235 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.04.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macar F., Anton J., Bonnet M., Vidal F. (2004). Timing functions of the supplementary motor area: an event-related fMRI study. Brain Res. Cogn. Brain Res. 21, 206–215 10.1016/j.cogbrainres.2004.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macar F., Coull J. T., Vidal F. (2006). The supplementary motor area in motor and perceptual time processing: fMRI studies. Cogn. Process. 7, 89–94 10.1007/s10339-005-0025-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macar F., Lejeune H., Bonnet M., Ferrara A., Pouthas V., Vidal F., Maquet P. (2002). Activation of the supplementary motor area and of attentional networks during temporalprocessing. Exp. Brain Res. 142, 475–485 10.1007/s00221-001-0953-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald V., Halliday G. M. (2002). Selective loss of pyramidal neurons in the pre-supplementary motor cortex in Parkinson's disease. Mov. Disord. 17, 1166–1173 10.1002/mds.10258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matell M. S., Meck W. H. (2004). Cortico-striatal circuits and interval timing: coincidence detection of oscillatory processes. Brain Res. Cogn. Brain Res. 21, 139–170 10.1016/j.cogbrainres.2004.06.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merchant H., Luciana M., Hooper C., Majestic S., Tuite P. (2008). Interval timing and Parkinson's disease: heterogeneity in temporal performance. Exp. Brain Res. 184, 233–248 10.1007/s00221-007-1097-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mita A., Mushiake H., Shima K., Matsuzaka Y., Tanji J. (2009). Interval time coding by neurons in the presupplementary and supplementary motor areas. Nat. Neurosci. 12, 502–507 10.1038/nn.2272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Boyle D. J., Freeman J. S., Cody F. W. J. (1996). The accuracy and precision of timing of self-paced, repetitive movements in subjects with Parkinson's disease. Brain 119, 51–70 10.1093/brain/119.1.51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Reilly J. X., Mesulam M. M., Nobre A. C. (2008). The cerebellum predicts the timing of perceptual events. J. Neurosci. 28, 2252–2260 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2742-07.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pastor M. A., Artieda J., Jahanshahi M., Obeso J. A. (1992). Time estimation and reproduction is abnormal in Parkinson's disease. Brain 115, 211–225 10.1093/brain/115.1.211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pastor M. A., Macaluso E., Day B. L., Frackowiak R. S. J. (2006). The neural basis of temporal auditory discrimination. Neuroimage 30, 512–520 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.09.053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penfield W. (1950). The supplementary motor area in the cerebral cortex of man. Arch. Psychiatr. Nervenkr. Z. Gesamte Neurol. Psychiatr. 185, 670–674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picard N., Strick P. L. (2001). Imaging the premotor areas. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 11, 663–672 10.1016/S0959-4388(01)00266-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pouthas V., George N., Poline J., Pfeuty M., Van de Moorteele P., Hugueville L., Ferrandez A., Lehéricy S., LeBihan D., Renault B. (2005). Neural network involved in time perception: an fMRI study comparing long and short interval estimation. Hum. Brain Mapp. 25, 433–441 10.1002/hbm.20126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartze M., Rothermich K., Kotz S. A. (in press). Functional dissociation of pre-SMA and SMA-proper in temporal processing. Neuroimage. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.11.089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sen S., Kawaguchi A., Truong Y., Lewis M. M., Huang X. (2010). Dynamic changes in cerebello-thalamo-cortical motor circuitry during progression of Parkinson's disease. Neuroscience 166, 712–719 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.12.036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman S. M. (2001). A wake-up call from the thalamus. Nat. Neurosci. 4, 344–346 10.1038/85973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman S. M. (2007). The thalamus is more than just a relay. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 17, 417–422 10.1016/j.conb.2007.07.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman S. M., Guillery R. W. (2002). The role of the thalamus in the flow of information to the cortex. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 357, 1695–1708 10.1098/rstb.2002.1161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shima K., Tanji J. (2006). Binary-coded monitoring of a behavioral sequence by cells in the pre-supplementary motor area. J. Neurosci. 26, 2579–2582 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4161-05.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith J. G., Harper D. N., Gittings D., Abernethy D. (2007). The effect of Parkinson's disease on time estimation as a function of stimulus duration range and modality. Brain Cogn. 64, 130–143 10.1016/j.bandc.2007.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer R. M. C., Karmarkar U., Ivry R. B. (2009). Evaluating dedicated and intrinsic models of temporal encoding by varyi ng context. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 364, 1853.1863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens M. C., Kiehl K. A., Pearlson G., Calhoun V. D. (2007). Functional neural circuits for mental timekeeping. Hum. Brain Mapp. 28, 394–408 10.1002/hbm.20285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanji J. (1996). New concepts of the supplementary motor area. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 6, 782–787 10.1016/S0959-4388(96)80028-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Nuenen B. F. L., van Eimeren T., van der Vegt J. P. M., Buhmann C., Klein C., Bloem B. R., Siebner H. R. (2009). Mapping preclinical compensation in Parkinson's disease: an imaging genomics approach. Mov. Disord. 24, S703–S710 10.1002/mds.22635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu T., Hallett M. (2005). A functional MRI study of automatic movements in patients with Parkinson's disease. Brain 128, 2250–2259 10.1093/brain/awh569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziegler W., Kilian B., Deger K. (1997). The role of the left mesial frontal cortex in fluent speech: evidence from a case of left supplementary motor area hemorrhage. Neuropsychologia 35, 1197–1208 10.1016/S0028-3932(97)00040-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]