Abstract

We report on a new familial neurodegenerative disease with associated dementia that has presented clinically in the fifth decade, in both genders, and in each of several generations of a large family from New York State—a pattern of inheritance consistent with an autosomal dominant mode of transmission. A key pathological finding is the presence of neuronal inclusion bodies distributed throughout the gray matter of the cerebral cortex and in certain subcortical nuclei. These inclusions are distinct from any described previously and henceforth are identified as Collins bodies. The Collins bodies can be isolated by simple biochemical procedures and have a surprisingly simple composition; neuroserpin (a serine protease inhibitor) is their predominant component. An affinity-purified antibody against neuroserpin specifically labels the Collins bodies, confirming their chemical composition. Therefore, we propose a new disease entity—familial encephalopathy with neuroserpin inclusion bodies (FENIB). The conclusion that FENIB is a previously unrecognized neurodegenerative disease is supported by finding Collins bodies in a small kindred from Oregon with familial dementia who are unrelated to the New York family. The autosomal dominant inheritance strongly suggests that FENIB is caused by mutations in the neuroserpin gene, resulting in intracellular accumulation of the mutant protein.

Degenerative diseases of the central nervous system (CNS) are a heterogeneous group of disorders with diverse clinical presentations, neuropathological findings, and pathogenic bases. In recent years much progress has been made in understanding the biology of these diseases. Genetic analysis of human populations, large families, and transgenic-animal models has advanced our understanding by identifying mutations in specific disease-associated genes.1-4 Yet the final diagnosis of most of these conditions still rests with the identification of specific gross and microscopic changes in central nervous tissue.5 Cellular inclusions, affecting both neurons and glia, are prominent features of many of these disorders; they can be recognized by histomorphology and ultrastructure, by histochemical staining properties, and by immunohistochemical characterization.6-8 We have used these strategies together with elementary biochemical techniques to investigate a novel neurodegenerative disease characterized by unusual neuronal inclusions in a large kindred from New York State. This disease typically manifests itself in the fifth decade of life and is characterized by an insidious onset of cognitive decline, impairment of attention and concentration, and perseveration, and loss of daily living skills exemplified by poor judgment and lack of insight. Learning and memory are also affected but to a lesser degree than is typically seen in Alzheimer’s disease. The principle neuropathological finding is the presence of round, eosinophilic, periodic acid/Schiff reagent (PAS)-positive, but diastase-resistant neuronal inclusion bodies distributed throughout the deeper layers of the cerebral cortex and in many subcortical nuclei, especially the substantia nigra. They are rarely seen in white matter. Extensive histochemical, immunohistochemical, and electron microscopic analyses show that these inclusions are distinct from any described previously.9 The finding that these histologically unique inclusion bodies are also chemically distinct, being composed predominately of neuroserpin (a serine protease inhibitor), leads us to conclude that we have discovered a new disorder—familial encephalopathy with neuroserpin inclusion bodies (FENIB). Evidence is presented showing that FENIB also occurs in an unrelated family from Oregon. The significance of our findings is that we can now study the mechanism of self-aggregation and tissue deposition of neuroserpin, how this causes neurodegeneration, and why this presents as dementia. Ultimately this information should advance our understanding of the biology of this group of disorders, because, despite their diversity, some common principles are emerging, particularly, the role that aberrant protein expression and processing play in producing the characteristic disease phenotype.

Materials and Methods

Gross and Microscopic Examinations

Entire brains of two affected individuals from the New York family were available for study; they were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for 2 weeks before gross examination and sectioning. Blocks were obtained from representative cortical and subcortical areas, embedded in paraffin, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), according to routine histological procedures. Prepared glass slides from another case, stained with H&E/Luxol fast blue, as well as flash-frozen sections of one hemisphere were provided by the Harvard Brain Tissue Resource Center (PHSMH31862). Portions of fixed brain tissue from an additional case, as well as fixed tissue from other organs from two cases, were obtained from regional tissue archives. Microscopic glass slides of formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded cerebral biopsy tissue from the Oregon family were supplied by the University of Washington School of Medicine (Seattle, WA) and were the only samples available for histological study of this family. Enzyme digestion studies were conducted with porcine pancreas α-amylase, 10 mg/ml, pH 6.8, at 37°C; barley β-amylase, 0.1 mg/ml, pH 4.8, at 37°C; and Aspergillus nigra amyloglucosidase, 0.1 mg/ml, pH 4.8, at 37°C. Dimedone (5,5-dimethyl-1,3 cyclo-hexanedione) was obtained from Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO, and was used as a 5% ethanolic solution at 60°C by the procedure of Bulmer.10 All other histochemical procedures were performed by routine histological laboratory protocols. All light microscopy was done on an Olympus microscope.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunostaining was performed on tissue fixed in 10% buffered formalin for at least 2 weeks and embedded in paraffin before staining. Commercially available antibodies were obtained and used as follows, for standard epitope retrieval techniques, strepavidin-biotin methodology, and 3–3′ diaminobenzidine as chromogen; ubiquitin (polyclonal, 1:400; Vector-NovoCastra, Burlingame, CA); α B-crystallin (polyclonal, 1:80; Vector-NovoCastra); amyloid-β (Aβ) (monoclonal, 1:80; Vector-NovoCastra); tau (monoclonal, 1:250; Labvision, Fremont, CA); neurofilament protein (monoclonal, 1:200; DAKO, Carpenteria, CA); phosphorylated neurofilament protein (SM1–31) (monoclonal, 1:200; Sternberger Monoclonals, Baltimore, MD); nonphosphorylated neurofilament protein (SM1–32) (monoclonal, 1:2000; Sternberger Monoclonals); synaptophysin (polyclonal, 1:500; DAKO); neuron-specific enolase (polyclonal, 1:40; Biogenex, San Ramon, CA); lysozyme (polyconal, 1:1000; Biogenex); antichymotrypsin (polyclonal, prediluted; Signet, Dedham, MA); antitrypsin (polyclonal, prediluted; Signet); actin (monoclonal, 1:400; DAKO); GFAP (polyclonal, 1:2000; DAKO); PGP9.5 (polyclonal, 1:3000; Vector); HSP27 (monoclonal, 1:100; Biogenesis, Portsmoth, NH); HSP70 (monoclonal, 1:200; Stressgen, Victoria, BC, Canada); superoxide dismutase (monoclonal, 1:8000; Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, IN); amyloid-β precursor protein (APP) (monclonal, 1:100; Boehringer Mannheim); and α-synuclein (1:500; Chemicon, Temecula, CA). An affinity-purified, polyclonal rabbit antibody to recombinant human neuroserpin was produced11-12 and was used at a 2000-fold dilution.

Lectin Histochemistry

Lectin histochemistry studies were performed on unfixed, frozen sections of cerebral cortex from a case and an age-matched control. A total of 21 fluorescein-labeled lectins available in three kits (Vector) were applied and viewed by fluorescence microscopy on a Leitz microscope.

Electron Microscopy

Tissue from the brain of one affected individual, including cerebral cortex, cingulate gyrus, substantia nigra, and subcortical white matter, was processed for electron microscopy (EM). Tissue was fixed initially for at least 2 weeks in 10% buffered formalin and was subsequently fixed overnight in 2.5% glutaraldehyde, postfixed for 1 hour in 1% osmium tetroxide, and embedded in Araldite 502 from which 1-mm-thick sections were cut and stained with toluidine blue. Ultra-thin sections of selected areas were stained with lead citrate and uranyl acetate and examined with a Jeol 100 SX electron microscope.

Biochemical Methods

Homogenization and Isolation of Inclusions

Cortical tissue (2 g) was homogenized in 10 ml of 250 mmol/L sucrose and 10 mmol/L ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, buffered to pH 7.4 with 10 mmol/L 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid containing 10 μl of Sigma protease inhibitor cocktail. The homogenate was filtered through gauze, and the retentate was washed with an additional 5 ml of homogenization medium. Verification that the inclusion bodies withstood the homogenization was accomplished by visualization using light microscopy after H&E staining by air drying a sample on a glass slide followed by fixing for 1 minute in absolute ethanol before H&E. Similarly, the assay used to monitor the fractionation of the inclusions throughout the isolation procedure was light-microscopic visualization after H&E staining. The inclusion bodies were isolated from the homogenate as follows: the homogenate was centrifuged at 1000 × g for 10 minutes, the supernatant decanted, and the soft pellet resuspended in 5 ml of homogenization medium; 5 ml of 1% sarcosyl in homogenization medium was added, the suspension was incubated at 37°C for 30 minutes with frequent mixing and centrifuged at 45,000 × g for 20 minutes; the pellet was resuspended in 10 ml of the 1% sarcosyl solution and incubated at 37°C for 30 minutes with frequent mixing and again subjected to centrifugation at 45,000 × g for 20 minutes; the pellet was resuspended in 5 ml of homogenization medium, 5 ml of collagenase (2 mg/ml) was added, and the suspension was incubated at 37°C for 60 minutes followed by centrifugation at 45,000 × g for 20 minutes; and the resultant pellet was resuspended in 0.5 ml (1/20 original volume) of 4% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), 125 mM Tris-HCl (pH 6.8), 20% glycerol, 10% mercaptoethanol and heated at 75°C for various periods of time. After heating, the samples were subjected to centrifugation at 14,000 × g for 10 minutes, and the supernatant was removed and analyzed by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE).

SDS-PAGE

The samples were diluted 2:1 in 4% SDS, 20% glycerol, 10% mercaptoethanol, 50 mmol/L Tris-HCl (pH 6.8) before being subjected to SDS-PAGE in a Bio-Rad 7.5% Redi-gel in Tris/glycine/SDS buffer at 150 V for 1.25 hours. Fifty microliters of the various samples were analyzed. After electrophoresis the gels were stained with Coomassie blue and destained by standard procedures.

Amino Acid Sequence

After SDS-PAGE the samples were electrophoretically transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane at 250 mA for 1.5 hours and stained with Coomassie blue. The membrane was sent to the Biotech Center at Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, where the 57-kd band was excised and either sequenced directly for N-terminal analysis or first subjected to endoproteinase C digestion (EC 3.4.99.30). The resulting peptides were separated by reverse-phase chromatography, and selected peaks were then sequenced.

Chemicals

All of the routine chemicals (Tris, SDS, glycine, N-lauroylsarcosine), as well as the enzymes, were obtained from Sigma.

Results

The classification of FENIB as a novel neurodegenerative disorder is based on a battery of criteria including neuropathological, biochemical, and immunohistochemical analyses. A clinical investigation of the New York family is continuing. Thus far we have found the disease in two unrelated families. The findings, taken in total, describe a new neurological disorder that is associated with familial presenile dementia.

Neuropathological

Gross Examination

Two cases from the New York family were available for a complete neuropathological investigation of the brain. Both individuals, siblings aged 64 and 57 with clinical dementias of approximately 10 years’ duration, showed normal appearing sulci and gyri without atrophy and with transparent leptomeninges. Brain weights were 1530 and 1400 g, respectively. Examination of the bases of the brains disclosed no vascular malformations or significant atherosclerotic changes. Multiple coronal sections demonstrated slight ventricular dilatation together with normal appearing cortical gray, subcortical white, and deep gray matter structures free of encephalomalacia, hemorrhage, or discoloration. In both cases the substantia nigra, brainstem, and cerebellum were grossly unremarkable (data not shown).

Light Microscopy

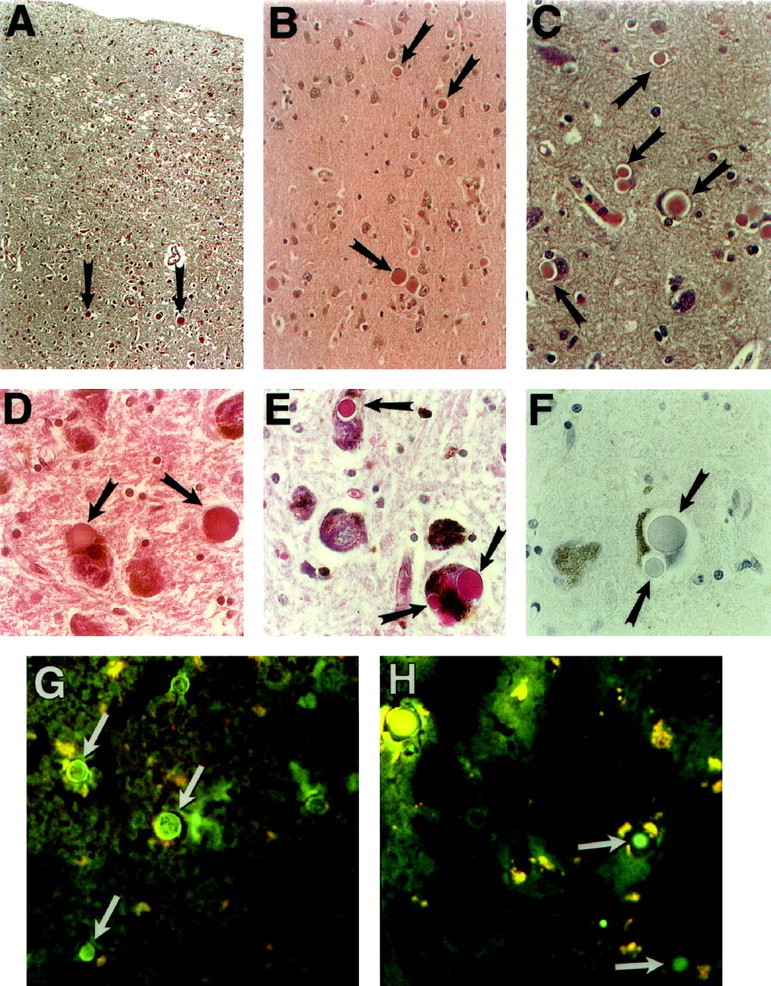

Sections of brain obtained from these two individuals and from a limited amount of autopsy material obtained from two additional family members were studied using standard histopathological methods. The neuropathological findings are presented in Figures 1 and 2▶ ▶ and in Tables 1–3▶ ▶ ▶ . Sections of brain stained with H&E were examined by light microscopy. At scanning magnification the neocortex shows mild microvacuolar change and gliosis affecting cortical layer II, principally in sections of the frontal, temporal, and parietal cortices (Figure 1A)▶ . Numerous, eosinophilic, sharply defined, round-to-oval inclusion bodies of variable size (approximately 5–50 μm) are scattered throughout the deeper layers of the cerebral cortex primarily in layers III to V (Figure 1A)▶ . They occur both singly and in clusters of three or more (Figure 1, B and C)▶ . Many of these inclusions are homogeneous in appearance, although others have either a dark core with a lighter halo or a variegated speckled appearance; a thin rim of darker material surrounds a few of them (Figure 1, B and C)▶ . Some of the inclusions are found within neuronal cell bodies, but many appear to lie free in the neuropil within vacuoles. The majority of cortical neurons are free of this involvement. Inclusions are very infrequently noted in the cerebral white matter. Deep gray matter is variably affected with marked involvement of the substantia nigra where many of the pigmented neurons show one or more inclusion bodies within their perikarya. However, neither neuronal loss nor gliosis are apparent. Many of the neurons affected with these bodies show no other abnormalities; however, others are grossly distorted, having no apparent cytoplasm, a displaced and compressed nucleus, and possibly an overall reduction in cell size. Neuronal loss is evident only in cortical layer II, and glial involvement is not seen except for the reactive change in layer II, as well as a low-grade subcortical gliosis. Histological examination of other organs disclosed only extensive myocardial fibrosis, severe coronary atherosclerosis, and pulmonary edema in one case, and hepatic steatosis in another case (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Histopathology of cerebral cortex and substantia nigra of an affected 57-year-old male (A–F) and an affected 60-year-old female (G and H). A: Low magnification shows microvacuolation and gliosis of layer II of cortex and several neuronal inclusions (arrows) in the deeper cortex (H&E staining; original magnification, ×40). B: Several inclusion bodies (arrows) in the deeper layers of frontal cortex (H&E staining; original magnification, ×200). C: Higher magnification (H&E staining; original magnification, ×400) shows inclusions within neuronal cytoplasm, compressing the remnant of a neuronal cell body and nucleus, and lying apparently free in the neuropil. D: Sections of substantia nigra pars compacta showing eosinophilic cytoplasmic inclusions of pigmented neurons superficially resembling Lewy bodies (H&E staining; original magnification, ×400). E: Unlike Lewy bodies, the inclusions are strongly PAS positive. Multiple inclusions affecting a single neuron are commonly seen (PAS staining; original magnification, ×400). F: Also in contrast to most Lewy bodies, the inclusions are nonreactive with ubiquitin immunohistochemistry (ubiquitin; original magnification, ×400). G and H: Fluorescein-labeled lectins applied to unfixed frozen sections of cerebral cortex and viewed by fluorescence microscopy (original magnification, ×250); G: Concanavalin A (specificity α- mannose, α- glucose); H: Lycopersicon esculentum (specificity (glc NAc)3).

Figure 2.

Togographic distribution of Collins bodies. Coronal sections of the cerebral hemispheres: frontal (A), frontotemporal (B and C), and parieto-occipital (D). Transverse sections: midbrain (E), pons and cerebellum (F and G), and medulla oblongata and cerebellum (H). The composite figure summarizes data obtained from four autopsy cases of FENIB. (Templates redrawn and modified with permission from the authors of ref. 52 ).

Table 1.

Anatomical Distribution of Inclusion Bodies

| Area | Occurrence | Specific location/comments |

|---|---|---|

| Cerebral cortex | +++ | In small to medium-sized neurons primarily in layers III through V |

| Insular cortex | +++ | |

| Cingulate gyrus | +++ | In small to medium size neurons in deeper layers |

| Claustrum | + | |

| Substantia innominata | − | |

| Hippocampal formation | ||

| Ammon’s horn | + | |

| Dentate gyrus | − | |

| Subiculum and parahippocampus | ++ | |

| Amygdala | ++ | Scattered inclusions |

| Thalamus and hypothalamus | + | Scattered inclusions in medial structures extending from mammillary nuclei to the region of the parafascicular nucleus |

| Basal ganglia | ||

| Caudate | + | In small neurons |

| Putamen | ++ | In small neurons |

| Globus pallidus | + | In small neurons |

| Midbrain | ||

| Substantia Nigra | ||

| ParsCompacta | +++ | Large or multiple intraneuronal inclusions in pigmented neurons |

| Par Retuculta | − | |

| Red Nucleus | ++ | |

| Nucleus of CN III | + | |

| Pons | ||

| Locus ceruleus | + | |

| Motor nucleus of CN V | + | |

| Medulla oblongata | + | Rare inclusion noted, including nucleus of CN XII and dorsal vagal nucleus |

| Cerebellum | − | |

| Spinal Cord | Not examined |

Table 2.

Histochemical Study of Inclusion Bodies

| Stain | Result | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| H&E | Pink/deep red | Eosinophilic |

| PAS | Homogeneous, magenta staining | Vicinyl hydroxyls |

| PAS after α-amylase | + | Vicinyl hydroxyls—not glycogen |

| PAS after dimedone | − | Not glycogen |

| Best’s carmine | − | Not glycogen |

| High-iron diamine | − | Not sulfated |

| Mucopolysaccharide | ||

| Alcian blue | − | Not acidic mucopolysaccharide |

| Cresyl violet | Blue | |

| Prussian blue | − | No iron |

| Von Kossa | − | No calcium |

| Alizarin red S | − | No calcium |

| Oil red-O (unfixed, frozen tissue) | − | Not neutral lipid |

| Sudan black B (unfixed, frozen tissue) | − | Not neutral lipid |

| Bodian | Gray-black | |

| Bielschowsky | Brown (diffuse plaques noted in one case) | Inconsistent with Alzheimer’s disease |

| Congo red | Orange | |

| No birefringence under polarized light | Not amyloid deposits |

Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue was used, except where indicated.

Table 3.

Immunohistochemistry of Inclusion Bodies

| Antigen | Immunohistochemistry result | Remarks |

|---|---|---|

| Tau | − | Not Pick bodies |

| Alpha-synuclein | − | Not Lewy bodies |

| Ubiquitin | − | No evidence of ubiquitin degradation pathway |

| PGP9.5 | − | No evidence of ubiquitin degradation pathway |

| Alpha B-crystallin | − | Heat shock proteins not detected |

| HSP 27 | − | Heat shock proteins not detected |

| HSP 70 | Heat shock proteins not detected | |

| Superoxide dismutase | − | No evidence of ALS-related inclusions |

| β-Amyloid | − | Inconsistent with Alzheimer’s disease |

| β-Amyloid precursor protein | − | Inconsistent with Alzheimer’s disease |

| GFAP | − | Mild cortical and subcortical gliosis |

| Actin | − | Not Hirano bodies |

| Neurofilament proteins | − | |

| Synaptophysin | − | |

| Neuron-specific enolase | − | |

| Lysozyme | − | |

| Antitrypsin | − | |

| Antichymotrypsin | − |

Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue was used for all the following experiments.

Sections of brain were examined by a variety of histochemical methods to elucidate the nature of the inclusion bodies. The results are shown in Figure 1▶ and in Table 2▶ . The inclusions are eosinophilic (Figure 1, A-D▶ ; Table 2▶ ) and are strongly and uniformly stained by the PAS method (Figure 1E)▶ . Furthermore, they retain their PAS reactivity after digestion by α-amylase or other glycosidases for up to 48 hours at 37°C (Table 2)▶ . Conversely, preincubation in 5% ethanolic dimedone, an aldehyde blocker, inhibits the PAS reaction (Table 2)▶ . The inclusions fail to stain with Best’s carmine (Table 2)▶ . These findings suggest that the inclusion bodies contain a carbohydrate component other than glycogen. Lack of staining with either the Alcian blue or the high-iron diamine method shows that the carbohydrate is not an acidic or a sulfated mucopolysaccharide (Table 2)▶ . Stains for neutral lipid, including Sudan black B and oil red O, are negative on unfixed frozen tissue (Table 2)▶ . Additional histochemical studies show that the inclusions are negative for iron and for calcium (Table 2)▶ . The inclusions were further analyzed using a screening panel of fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated lectins (Figure 1, G and H)▶ . By fluorescence microscopy, the presence of neuronal lipofuscin was apparent by its bright autofluorescence. Lectins showing moderate to strong affinity for the bodies included those with relative specificity for mannose (Figure 1G)▶ and for N-acetylglucosamine (Figure 1H)▶ . In summary, these findings suggest that the inclusions are composed of a glycoprotein or glycoproteins containing N-linked oligosaccharides.

Immunohistochemical methods were used to probe for known components of other well-characterized neuronal inclusions. The results are presented in Figure 1▶ and in Table 3▶ . As shown (Table 3▶ ; Figure 1F▶ ) the inclusions are negative for both ubiquitin and α-synuclein, and thus they are distinguishable from Lewy bodies13-15 ; they contain neither Aβ nor other abnormal proteins or peptides characteristic of Alzheimer’s disease. Furthermore, none of the following proteins are detected: intermediate filaments or other cytoskeletal proteins, PGP9.5, α B-crystallin, heat shock proteins 27 or 70, superoxide dismutase, or tau (Table 3)▶ . Neither Pick bodies nor ballooned neurons are seen. Tau-positive glial inclusions are not identified. Rare tau-positive neurofibrillary tangles are observed in the hippocampal formation. An antibody to synaptophysin strongly labels the cortical neuropil but not the inclusions. Thus, the inclusion bodies described here appear to be distinctly different from any described previously; therefore we propose the name Collins bodies to identify these unique inclusions. Their neuroanatomical mapping is shown in Figure 2▶ .

Electron Microscopy

By transmission EM, Collins bodies appear as moderately osmiophilic round globules with an amorphous to finely granular texture (Figure 3)▶ . They have little internal structure, aside from some speckling with darker material, and a few demonstrate a darker inner core contrasting with a lighter outer shell. Most are well delimited at their periphery, sometimes crowding aside other cytoplasmic organelles; others appear to be enclosed within a limiting membrane of rough endoplasmic reticulum (Figure 3)▶ .

Figure 3.

Transmission electron micrographs of inclusion bodies in cerebral cortex. A: Three inclusions in the cytoplasm of a cortical neuron. The nucleus shows only slight compression (original magnification, ×4000). B: Higher magnification of another inclusion body. Note amorphous, finely granular composition and apparent limiting membrane (original magnification, ×20,000).

Biochemical

Isolation of Collins Bodies

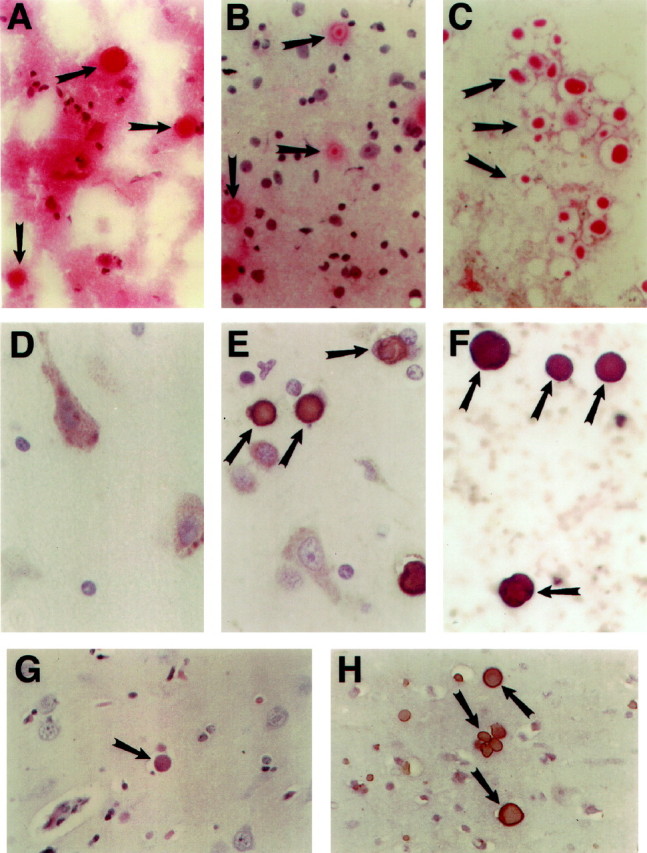

The Collins bodies were isolated from unfixed, frozen cerebral cortex tissue by homogenization in a buffered isotonic sucrose solution, washed with detergent (N-lauroylsarcosine), digested with collagenase, washed, and collected by centrifugation (Figure 4▶ ; see Materials and Methods for complete details). The presence of Collins bodies was monitored throughout the isolation procedure by light microscopy after H&E staining; as noted, they are eosinophilic (Figure 5, A-C▶ ). Clearly, a highly enriched preparation is obtained (the H&E stain of the enriched fraction that is labeled fraction P5 in Figure 4▶ is presented in Figure 5 C▶ ), although the bodies appear to be damaged somewhat (compare Figures 5A and 5C▶ ).

Figure 4.

Isolation of inclusion bodies. The inclusions were isolated from 2 g of frozen cerebral cortical tissue obtained at autopsy from an affected individual. The presence of the inclusion bodies was monitored throughout the isolation by light microscopy after alcohol fixation and H&E staining. Complete details of the isolation are given in Materials and Methods.

Figure 5.

Visualization of inclusions by histochemistry and immunohistochemistry. The various fractions obtained during the isolation scheme were assayed for the presence of the inclusions by H&E staining (original magnification, ×400) (A–C). A: Starting material (unfixed, frozen brain tissue). B: Fraction labeled P1 in Figure 4▶ . C: Fraction identified as P5 in Figure 4▶ . The presence of neuroserpin was detected with a neuroserpin-specific polyclonal antibody (D–F; original magnification, ×400). D: Cortical tissue from an age- and gender-matched control; E: Cortical tissue from an affected individual; F: Fraction labeled P5 in Figure 4▶ . Tissue from an affected individual from the Oregon family. G: Cortical tissue stained with H&E (original magnification, ×400). H: Cortical tissue stained with neuroserpin antibody (original magnification, ×400).

Protein Composition

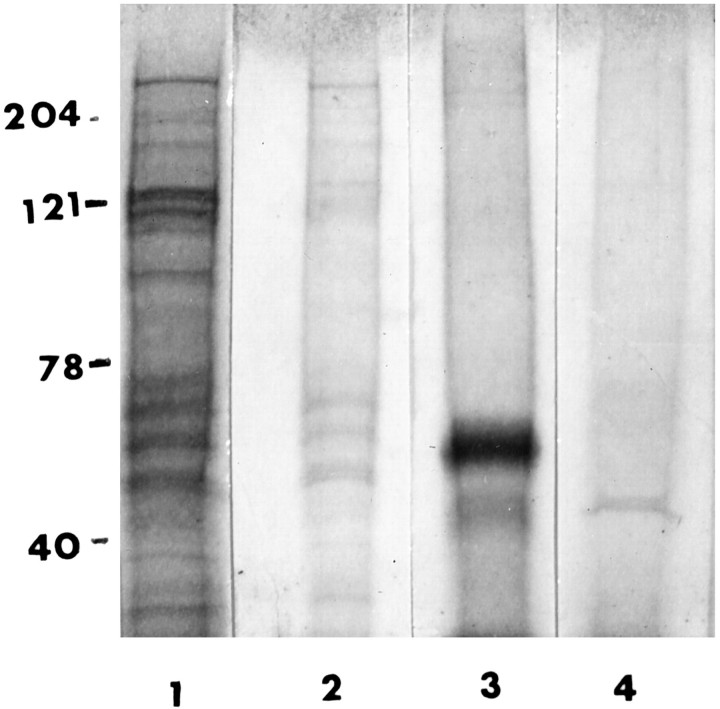

In preliminary experiments the fraction enriched with Collins bodies (fraction P5) was subjected to routine SDS-PAGE analysis, ie, heating for 5 minutes in boiling water in a 2% SDS-reducing buffer. However, this treatment released very little protein detectable by Coomassie blue staining (Figure 6▶ , lane 2 represents SDS-PAGE of fraction S6 obtained by heating for 5 minutes). Moreover, microscopic examination revealed that Collins bodies remained intact and could be collected by centrifugation (fraction P6). Therefore, the Collins body-enriched fraction (P5) was treated a second time and subjected to harsher conditions, heating for 2 hours at 75°C in 4% SDS. By this treatment the Collins bodies were disrupted, and SDS-PAGE analysis showed one prominent protein band at 57 kd (Figure 6▶ , lane 3, is fraction S6 obtained after prolonged heating). A 57-kd protein was not found in an identically treated specimen obtained from an age- and gender-matched control (Figure 6▶ , lane 4).

Figure 6.

SDS-PAGE. Fractions obtained from the isolation procedure were visualized by Coomassie blue staining after SDS-PAGE in a 7.5% gel. Lane 1: Homogenate. Lane 2: Fraction S6 obtained after heating P5 in SDS for 5 minutes at 75°C. Lane 3: Fraction S6 obtained after heating P5 in SDS for 2 hours at 75°C. Lane 4: Fraction S6 obtained from age- and gender-matched control tissue. (Fraction S6 was obtained by resuspending the Collins body-enriched fraction (P5) in a volume of 4% SDS equal to 1/20 the original homogenization volume, heating for the various times as noted, and centrifuging for 5 minutes. The supernatant (50 μl) was applied to the gel.

Protein Identification

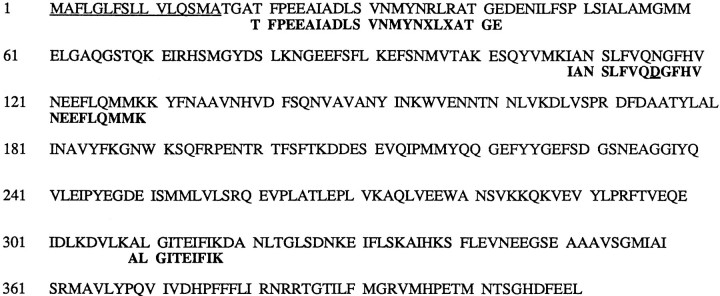

The results show that Collins bodies are composed primarily of a single protein. The identity of the 57-kd protein was determined by transferring it to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane and subjecting it to amino acid sequence analysis before and after proteolytic digestion (see Materials and Methods). The sequence information was analyzed using the BLAST program and gave convincing evidence that the 57-kd protein is neuroserpin (Figure 7)▶ , a serine protease inhibitor synthesized primarily in the CNS. Differences between the amino acid composition of the isolate and the wild-type neuroserpin were found: 1) asparagine 100 in the wild type is identified as aspartic acid in the isolate (most likely, this difference is an artifact because, when an asparagine residue is followed by a glycine in the primary structure, the asparagine frequently becomes deamidated during the sequencing procedure), and 2) the N-terminal amino acid of the isolate corresponds to residue number 20, not number 17 as expected. (Reportedly the first 16 residues serve as the single peptide.11,16 ) Nonetheless there is sufficient identity between the isolate and the amino acid sequence of neuroserpin to confidently state that Collins bodies are composed of neuroserpin.

Figure 7.

Identification of 57-kd protein. The 57-kd protein isolated from inclusion bodies was identified by its amino acid sequence. The N-terminal and internal peptide compositions of the protein were determined, and the resulting sequence information was analyzed by the BLAST program. The primary structure of human neuroserpin is presented in the top line. The first 16 amino acids are underlined and reportedly represent the signal sequence. The alignment of the peptides identified for the 57-kd protein is presented in bold letters below the known sequence. The only difference found between the wild-type neuroserpin and the 57-kd protein is a change of an aspartate for an asparagine at position 100 in the wild-type.

Immunological

New York Family

The cellular distribution of neuroserpin is very different between an age- and gender-matched control (Figure 5D)▶ and an affected subject (Figure 5E)▶ . In the control, the neuroserpin-staining pattern is generally diffuse, although small punctate foci of more intense staining are occasionally seen. Conversely, in the affected individual (Figure 5E)▶ neuroserpin is aggregated into inclusions that correspond by size and distribution to Collins bodies. Furthermore, the inclusion body-enriched fraction stains intensely with a neuroserpin antibody (Figure 5F)▶ . These immunohistochemical findings support the conclusion that Collins bodies contain neuroserpin.

Oregon Family

Pathological and immunohistochemical analyses of brain tissue obtained by biopsy from one member of the Oregon family, who was originally classified as suffering from an unclassified inclusion body dementia,17 are shown (Figure 5, G and H)▶ . The inclusion bodies are similar in size, H&E staining (Figure 5G)▶ , and distribution, to those seen in the New York family. Furthermore, they stain positively for neuroserpin (Figure 5H)▶ .

Pedigree

The familial occurrence of FENIB in the New York kindred is apparent by examination of the pedigree (Figure 8)▶ . The disease appears in each of four generations and in both genders, a pattern of inheritance consistent with an autosomal dominant mode of transmission. Some affected individuals were identified by either family history or clinical evaluation. (The clinical evaluation of the family is continuing.) Affected subjects present with deficits in attention and concentration, perseveration, and restricted oral fluency. More severely affected subjects demonstrate additional difficulties including restricted visuospatial organization and visuoconstructional problem solving. They experience progressive difficulties organizing their activities of daily living. Although they demonstrate impaired learning and memory in the earlier stages, it is to a lesser extent than typically seen in early Alzheimer’s disease and is characterized by restricted learning with more spared recall of information that has been learned. Single photon emission computed tomography cerebral perfusion studies have shown areas of cortical hypoperfusion, involving especially the interior frontal and adjacent temporal and parietal cortices in affected subjects. Magnetic resonance imaging studies are essentially normal in younger, mildly affected subjects, but demonstrate diffuse cortical atrophy in moderately to severely demented older individuals. Electroencephalogram patterns show primarily generalized slowing, consistent with diffuse cortical dysfunction, although one subject also showed intermittent triphasic wave activity (data not shown). The course of the disease can be quite long, exceeding 10 years in some cases. Most patients will eventually require institutional care.

Figure 8.

Pedigree. The familial occurrence of the disease. Individuals were

classified as affected by one of three categories: family history

( ); clinically (

); clinically ( );

or neuropathologically

(⋄).

Unaffected individuals are indicated by open symbols

(⋄).

The pedigree has been modified to protect the family’s privacy.

Deceased individuals are not indicated. Roman numerals refer to the

generation, Arabic numbers to individuals within that

generation.

);

or neuropathologically

(⋄).

Unaffected individuals are indicated by open symbols

(⋄).

The pedigree has been modified to protect the family’s privacy.

Deceased individuals are not indicated. Roman numerals refer to the

generation, Arabic numbers to individuals within that

generation.

Discussion

A large number of distinct familial neurodegenerative diseases causing early-adult-onset dementia have been described.18 Many of these can be neuropathologically recognized and categorized by the presence, staining properties, and distribution of neuronal inclusions or other abnormal proteinaceous deposits in the CNS. In this study we describe a new neurodegenerative disease whose key pathological finding is the presence of unique neuronal inclusion bodies distributed throughout the gray matter of the cerebral cortex, especially the neurons of layers III to V, and in selected subcortical nuclei (Table 1▶ ; Figures 1 and 2▶ ▶ ). We refer to these unique inclusions as Collins bodies, in recognition of Dr. George H. Collins, who initiated this study. We find that the Collins bodies are composed primarily of neuroserpin, and consequently we name this disease familial encephalopathy with neuroserpin inclusion bodies (FENIB).

The Collins bodies are distinguishable from other well-characterized inclusions. Their PAS positivity, but negativity for ubiquitin and α-synuclein (as shown in Table 3▶ and Figure 1▶ ) clearly differentiates them from Lewy bodies.14,15,19 Collins bodies are also easily distinguished from the more basophilic, argyrophilic, and tau-positive bodies of classic Pick’s disease6,20 (Table 3)▶ . They do not appear to be related to protein dense microspheres or spherons, which have recently been shown to contain the Aβ precursor protein and the Aβ 1–40 peptide.21,22 Collins bodies are nonreactive with a large panel of neuroimmunohistochemical reagents (Table 3)▶ , and they defy precise classification by routine methods. They are also different from other types of PAS-positive inclusions, including corpora amylacea, Lafora bodies, Bielschowsky bodies, the inclusions of type IV glycogenosis, and the polyglucosan bodies of adult polyglucosan body disease.23-29 First, Collins bodies retain PAS positivity even after prolonged incubation with glycosidases in contrast to the aforementioned inclusions, which are degraded enzymatically.24 Second, corpora amylacea, Lafora bodies, and polyglucosan bodies are resistant to the aldehyde-blocking reagent dimedone,28 in contrast to the Collins bodies, which lose PAS staining after a brief exposure to this reagent (Table 2)▶ . Third, the lectin-binding specificities of the Collins bodies are consistent with the conclusion that they contain significant amounts of mannose and N-acetylglucosamine (Figure 1, G and H)▶ , as might be found in an N-linked glycoprotein, in contrast to other PAS-positive inclusions that contain a high proportion of a glycogenlike substance and only a small percentage of protein.28,29 Finally, Collins bodies are distinguished ultrastructurally by a rather homogeneous, finely granular appearance, sometimes bounded by a membrane, whereas polyglucosan bodies, such as those of Lafora, show primarily fibrils and filaments, which may be branched, with a variable granular component, and they never have a limiting membrane.26,29

In addition to these classically described types of PAS-positive inclusions, atypical myoclonus bodies (myoclonus body type II) have been reported in a disorder that Berkovic calls atypical inclusion body-progressive myoclonus epilepsy.30,31 Only a few case reports have appeared describing this condition, which manifests with myoclonus, seizures, and progressive neurological dysfunction, including dementia, beginning from childhood to young adulthood.32-35 The inclusions differ from Lafora bodies and resemble Collins bodies in their staining properties (Alcian blue negative), ultrastructure (nonfibrillar), and distribution (confined to brain). Two of the present authors have previously described a case of seizures and progressive neurological dysfunction in a young woman with atypical neuronal inclusions.17 Since the initial case report, one of the subject’s daughters has developed a seizure disorder and progressive cognitive loss starting at age 18, suggesting that this is a familial disease (Oregon family). Pathological and immunohistochemical analyses of brain tissue obtained by biopsy from one member of this family are shown (see Figure 5, G and H▶ ). The inclusion bodies are similar in size, histochemistry, and distribution to Collins bodies (see Figure 5G▶ ), and they stain positively with a neuroserpin-specific antibody (see Figure 5H▶ ). We therefore conclude that the Oregon kindred is also affected by FENIB. The relationship of FENIB to other cases demonstrating atypical inclusion bodies is presently unknown.

The chemical composition of Collins bodies appears to be surprisingly simple; they are composed primarily of neuroserpin (Figures 4–6)▶ ▶ ▶ . Neuroserpin is a member of a large family of structurally related proteins called serpins (serine protease inhibitors). The family is divided into two subclasses: those with and those without antiproteolytic activity.36,37 Those members that are protease inhibitors share the property of unusual conformational mobility—the capacity to undergo dramatic changes in shape.38,39 This molecular mobility provides the serpins with an evolutionary advantage of not only being capable of binding their target protease, but also of entrapping it in a highly stable complex that persists for the minutes or even hours needed to clear the complex from the extracellular fluid compartment. The trapping mechanism has been compared with that of a mousetrap—the serpin is synthesized in a metastable state (ie, the trap is set during biosynthesis) with an extended reactive site loop (ie, the cheese) that acts as the substrate (ie, the bait) for the target protease (ie, the prey). When the prey takes the bait, the serpin snaps closed (in actuality, relaxes to a more stable conformation), pulling the target protease into a stable complex and thus stopping the extracellular proteolytic cascade. Conversely, an evolutionary disadvantage of the serpin’s requirement of high molecular mobility is the propensity to form dysfunctional molecules; a single amino acid change in certain key domains of the molecule results in the loss of the crucial folding information needed to form the metastable intermediate(s); the trap closes prematurely. The end result is the polymerization of mutant serpin molecules into intracellular aggregates.39,40 A well-characterized example of a mutant serpin that results in a disease is the α 1-antitrypsin (α AT) deficiency syndrome commonly found in Northern Europeans.40-42 Most individuals have the normal M form of α AT, but 4% are heterozygous for the Z variant. (The name antitrypsin is a misnomer because the actual target protease is not trypsin but elastase, an enzyme secreted by neutrophils in response to inflammation. It is therefore now called α 1-proteinase inhibitor.) The Z mutation involves a single amino acid change at the base of the extended reactive center such that the reactive loop of one molecule binds or folds with adjacent molecules to form polymers. This self-association prevents normal α AT processing by the hepatocytes and results in a loss of α AT secretion. Although clinical disease is manifested generally only in homozygous individuals, MZ heterozygotes do have the hepatic inclusion bodies.43 It is more interesting and most important that the histochemistry of the α AT inclusions produced in the liver of those individuals expressing the Z variant is very similar to the neuroserpin aggregates or Collins bodies observed in the brain in the neurodegenerative disease under study.

The findings presented are consistent with the hypothesis that FENIB is caused by a mutation in the neuroserpin gene that results in the polymerization and aggregation of the neuroserpin protein. The findings supporting this conclusion are the following: first, FENIB is a familial disease with apparent autosomal dominant transmission, indicating that the expression of the mutant allele is sufficient to produce the disease; second, there is a striking similarity in appearance between Collins bodies and the α AT inclusions found in the liver of individuals affected with the Z variant; and third, the chemical composition of Collins bodies is unique compared with other neuronal inclusions, consisting almost entirely of neuroserpin. These points are consistent with the interpretation that a single molecular defect triggers the pathogenic cascade. The hypothesis was tested by subjecting the two families experiencing FENIB to genetic analysis. We have found that all of the clearly affected individuals in the New York family express a missense mutation in the neuroserpin gene, a serine-to-proline transition at amino acid position 49.44 Affected individuals in the Oregon family show a serine-to-arginine change at position 52.44 Thus we conclude that FENIB is a genetic disease caused by mutations in critical regions of the neuroserpin protein resulting in polymerization and tissue deposition—the identical sequence of events generated by mutations in the gene encoding α AT.

The causal relationship between neuroserpin deposition and the onset of the clinical syndrome is not clear. Neuroserpin is believed to play a vital role in controlling extracellular proteolysis in the nervous system, especially as an inhibitor of tissue-type plasminogen activator.45 Proteolytic cascades appear to be involved in the processes of synaptic remodeling, repair, and regeneration in the CNS.45-48 Consequently, a diminution in neuroserpin secretion could result in uncontrolled proteolysis with a subsequent decrease in synaptic contacts and the loss of neuronal function. It is equally conceivable that the inclusions themselves are neurotoxic. Future studies will have to determine how common neuroserpin mutations are, and why they cause neurological disease. We think that these are particularly pertinent questions because there is an emerging concept that many, if not all, neurodegenerative diseases are the result of intra- or extracellular deposits of misfolded or mutant proteins.49,50 FENIB may present a simple model to test this hypothesis.51 Ultimately it may be possible to propose common mechanisms of pathogenesis and to promote common therapies for this heterogeneous group of CNS disorders.49-51

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ms. Janet Jackson for all of her secretarial and managerial assistance. We also thank Ms. Kathy Pelton-Henrion, Ms. Maureen Barcza, Mr. David Welker, Mr. Mark Chilton, and Ms. Donna Barrett for technical assistance and Dr. Robert Schelper, Dr. Robin Carrell, and Dr. David Lomas for their thoughtful suggestions and enthusiastic support.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Dr. Peter D. Holohan, Department of Pharmacology, SUNY Health Science Center at Syracuse, 750 East Adams Street, Syracuse, NY 13210. E-mail: HolohanP@vax.cs.hscsyr.edu.

Supported by CAP Foundation Award (to R. L. D.), SUNY HSC Hendricks Fund #130283 (to A. E. S.), and SUNY-HSC Hendricks Fund #13230 and NIHAG16954 (to P. D. H.).

References

- 1.Hardy J, Gwinn-Hardy K: Genetic classification of primary neurodegenerative disease. Science 1998, 282:1075-1079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Price DL, Sisodia SS, Borchelt DR: Genetic neurodegenerative disease: the human illness and transgenic models. Science 1998, 282:1079-1083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Muller U, Graeber MB: Neurogenetic diseases: molecular diagnosis and therapeutic approaches. J Mol Med 1996, 74:71-84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Giannakopoulos P, Hof PR, Savioz A, Guimon J, Antonarakis SE, Bouras C: Early-onset dementias: clinical, neuropathological and genetic characteristics. Acta Neuropathol 1996, 91:451-465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hart MN: Contributions of autopsy to modern neurologic science. Hill RB Anderson RE eds. The Autopsy: Medical Practice and Public Policy. 1988, :pp 91-105 Butterworths, Boston [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schochet SS: Neuronal inclusions. Bourne GH eds. The Structure and Function of Nervous Tissue, 1972, vol IV.:pp 129-177 Academic Press, New York, London, [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leigh PN, Probst A, Dale GE, Power DP, Brion JP, Dodson A, Anderton BH: New aspects of the pathology of neurodegenerative disorders as revealed by ubiquitin antibodies. Acta Neuropathol 1989, 79:61-72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cooper PN, Jackson M, Lennox G, Lowe J, Mann DMA: Tau, ubiquitin, and α B-crystallin immunohistochemistry define the principal causes of degenerative fronto temporal dementia. Arch Neurol 1995, 52:1011-1015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davis RL, Daucher JW, Welker DM, Barcza MA, Collins GH: A familial dementia with unusual neuronal inclusions. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 1996, 55:636(abstr.) [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bulmer D: Dimedone as an aldehyde blocking reagent to facilitate the histochemical demonstration of glycogen. Stain Technol 1959, 34:95-98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hastings GA, Coleman TA, Haudenschild CC, Stefansson S, Smith EP, Barthlow R, Cherry S, Sandkvist M, Lawrence DA: Neuroserpin, a brain-associated inhibitor of tissue plasminogen activator is localized primarily in neurons: implications for the regulation of motor learning and neuronal survival. J Biol Chem 1997, 272:33062-33067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shermann PM, Lawrence DA, Yang AY, Vandenberg ET, Paielli P, Olson ST, Shore JD, Ginsburg D: Saturation mutagenesis of the plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 reactive center. J Biol Chem 1992, 267:7588-7595 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lennox G, Lowe J, Landon M, Byrne EJ, Mayer RJ, Godwin-Austen RB: Diffuse Lewy body disease: correlative neuropathology using anti-ubiquitin immunocytochemistry. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1989, 52:1236-1247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fukuda T, Tanaka J, Watabe K, Numoto RT, Minamitani M: Immunohistochemistry of neuronal inclusions in the cerebral cortex and brain-stem in Lewy body disease. Acta Pathol Jpn 1993, 43:545-551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spillantini MG, Schmidt ML, Lee VML, Trojanowski JQ, Jakes R, Goedert M: Alpha-synuclein in Lewy bodies. Nature 1997, 388:839-840 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schrimpf SP, Bleiker AJ, Brecevic L, Kozlov SV, Berger P, Osterwalder T, Krueger SR, Schinzel A, Sonderegger P: Human neuroserpin (PI12): cDNA cloning and chromosomal localization to 3q26. Genomics 1997, 40:55-62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yerby MS, Shaw C-M, Watson JMD: Progressive dementia and epilepsy in a young adult: unusual intraneuronal inclusions. Neurology 1986, 36:68-71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cervós-Navarro J, Urich H: Metabolic and Degenerative Diseases of the Central Nervous System: Pathology, Biochemistry, and Genetics. 1995. Academic Press, San Diego,

- 19.Greenfield JG, Bosanquet FD: The brain-stem lesions in Parkinsonism. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1953, 16:213-226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Delacourte A, Robitalle YU, Sergeant N, Buee L, Hof PR, Wattez A, Laroche-Cholette A, Mathieu J, Chagnon P, Gauvreau D: Specific pathological tau protein variants characterize Pick’s disease. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 1996, 55:159-168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Averback P: Dense microspheres in normal human brain. Acta Neuropathol 1983, 61:148-152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Averback P, Morse D, Ghanbari H: Bursting dense microspheres (spherons) in Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimer’s Dis 1998, 1:1-34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yokoi S, Austin T, Witmer F, Sakai M: Studies in myoclonus epilepsy (Lafora body form). 1. Isolation and preliminary characterization of Lafora bodies in two cases. Arch Neurol 1968, 19:15-33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sakai M, Austin J, Witmer F, Trueb L: Studies of corpora amylaceal.1. Isolation and preliminary characterization by chemical and histochemical techniques. Arch Neurol 1969, 21:526-544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sakai M, Austin J, Witmer F, Trueb L: Studies in myoclonus epilepsy (Lafora body form). II. Polyglucosans in the systemic deposits of myoclonus epilepsy and in corpora amylacea. Neurology 1970, 20:160-176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Collins GH, Cowden RR, Nevis AH: Myoclonus epilepsy with Lafora bodies: an ultrastructural and cytochemical study. Arch Pathol 1968, 86:239-254 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schochet SS, McCormick WF, Zellweger H: Type IV glycogenosis (amylopectinosis): light and electron microscopic observations. Arch Pathol 1970, 90:354-363 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Robitaille Y, Carpenter S, Karpati G, DiMauro S: A distinct form of adult polyglucosan body disease with massive involvement of central and peripheral neuronal processes and astrocytes: a report of four cases and a review of the occurrence of polyglucosan bodies in other conditions such as Lafora’s disease and normal aging. Brain 1980, 103:315-336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cavanagh JB: Corpora-amylacea and the family of polyglucosan diseases. Brain Res Rev 1999, 29:265-295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Berkovic SF, Carpenter S, Andermann F: Atypical inclusion body progressive myoclonus epilepsy: a fifth case? Neurology 1986, 36:1275-1276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Berkovic SF, Andermann F, Carpenter S, Wolfe LS: Progressive myoclonus epilepsies: specific causes and diagnosis. N Engl J Med 1986, 315:296-305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dastur DK, Singhal BS, Gootz M, Seitelberger F: Atypical inclusion bodies with myoclonic epilepsy. Acta Neuropathol 1966, 7:16-25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bergener M, Gerhard L: Myoklonuskorperkrankheit und myoklonusepilepsie. Nervenarzt 1970, 41:166-173 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ota T, Hisatomi Y, Kashiwamura K, Otsu K, Nakamura Y, Takamatsu S, Mehraein P: Histochemistry and ultrastructure of atypical myoclonus body (type II). Acta Neuropathol 1974, 28:45-54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dolman C: Atypical myoclonus body epilepsy (adult variant). Acta Neuropathol 1975, 31:201-206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Potempa J, Korzus E, Travis J: The serpin superfamily of proteinase inhibitors: structure, function, and regulation. J Biol Chem 1994, 269:15957-15960 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Whisstock J, Skinner R, Lesk PM: An atlas of serpin conformations. Trends Biochem Sci 1998, 23:63-67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Carrell RW, Lomas DA: Conformational disease. Lancet 1997, 350:134-138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stein PE, Carrell RW: What do dysfunctional serpins tell us about molecular mobility and disease. Nat Struct Biol 1995, 2:96-113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Carrell RW, Lomas DA, Sidhar S, Foreman R: Alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency: a conformational disease. Chest 1996, 110:243S-247S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Elliott PR, Lomas DA, Carrell RW, Abrahams JP: Inhibitory conformation of the reactive loop of alpha1-antitrypsin. Nat Struct Biol 1996, 3:676-681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Elliott PR, Stein PE, Bilton D, Carrell RW, Lomas DA: Structural explanation for the deficiency of S Alpha1-antitrypsin. Nat Struct Biol 1996, 3:910-911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gordon HW, Dixon J, Rogers JC, Mittman C, Lieberman J: Alpha A1-antitrypsin (A1AT) accumulation in livers of emphysematous patients with A1AT deficiency. Hum Pathol 1972, 3:361-370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Davis RL, Shrimpton AE, Holohan PD, Bradshaw C, Feiglin D, Collins GH, Sonderegger P, Kinter J, Becker LM, Lacbawan F, Krasnewich D, Muenke M, Lawrence DA, Yerby MS, Shaw CM, Gooptu B, Elliot P, Finch JT, Carrell RW, Lomas DA: Familial dementia caused by polymerization of mutant neuroserpin. Nature 1999, 401:376-379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Osterwalder T, Cinelli P, Baici A, Pennella A, Krueger SR, Schrimpf SP, Meins M, Sonderegger P: The axonally secreted serine protease inhibitor, neuroserpin, inhibits plasminogen activators and plasmin but not thrombin. J Biol Chem 1998, 273:2312-2321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Smirnova IV, Ho GJ, Fenton II JW, Festoff BW: Extravascular proteolysis and the nervous system: serine protease/serpin balance. Semin Thromb Hemost 1994, 20:426–432 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 47.Strickland G, Gualandris A, Rogove AD, Tsirka SE: Extracellular proteases in neuronal function and degeneration. Cold Spring Harbor Symp Quant Biol 1996, 61:739-745 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Turgeon VL, Houenou LJ: The role of thrombin-like (serine) proteases in the development, plasticity and pathology of the nervous system. Brain Res Rev 1997, 25:85-95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kakizuka A: Protein precipitation: a common etiology in neurodegenerative disorders? Trends Genet 1998, 14:396-402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Goedert M: Filamentous nerve cell inclusions in neurodegenerative diseases: tauopathies and α-synucleinopathies. Phil Trans R Soc London Ser B 1999, 354:1101-1118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Carrell RW, Gooptu B: Conformational changes and disease-serpins, prions and Alzheimer’s. Curr Opin Struct Biol 1998, 8:799-809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Esiri MM, Oppenheimer DR: Diagnostic Neuropathology. 1989:pp 12-40 Blackwell Scientific, London,