Abstract

Ecotropic viral integration site 1 (EVI1) is an oncogenic dual domain zinc finger transcription factor that plays an essential role in the regulation of hematopoietic stem cell renewal, and its overexpression in myeloid leukemia and epithelial cancers is associated with poor patient survival. Despite the discovery of EVI1 in 1988 and its emerging role as a dominant oncogene in various types of cancer, few EVI1 target genes are known. This lack of knowledge has precluded a clear understanding of exactly how EVI1 contributes to cancer. Using a combination of ChIP-Seq and microarray studies in human ovarian carcinoma cells, we show that the two zinc finger domains of EVI1 bind to DNA independently and regulate different sets of target genes. Strikingly, an enriched fraction of EVI1 target genes are cancer genes or genes associated with cancer. We also show that more than 25% of EVI1-occupied genes contain linked EVI1 and activator protein (AP)1 DNA binding sites, and this finding provides evidence for a synergistic cooperative interaction between EVI1 and the AP1 family member FOS in the regulation of cell adhesion, proliferation, and colony formation. An increased number of dual EVI1/AP1 target genes are also differentially regulated in late-stage ovarian carcinomas, further confirming the importance of the functional cooperation between EVI1 and FOS. Collectively, our data indicate that EVI1 is a multipurpose transcription factor that synergizes with FOS in invasive tumors.

Keywords: MDS1 and EVI1 complex locus (MECOM), comparative genomics, DNA-binding motif, Yin and Yang 1 (YY1), paired box 2 (PAX2)

Ecotropic viral integration site 1 (EVI1) is a zinc finger (ZNF) transcription factor (TF), and its overexpression in myeloid leukemia (1–3) and epithelial cancers (1, 2, 4–9) has been extensively studied and correlated with adverse patient outcome (7, 10, 11). EVI1 also controls several aspects of embryonic development, including hematopoiesis, angiogenesis, and heart and neural development (12). Three major alternative splice forms of the MDS1 and EVI1 complex locus (MECOM) locus have been identified, including EVI1, EVI1Δ324, and MDS1-EVI1. The PRDI-BF1 and RIZ homology domain containing Myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS)1-EVI1 isoform acts as a tumor suppressor gene, whereas the shorter isoforms, EVI1 and EVI1Δ324, that lack this domain display oncogenic functions (13). The most oncogenic isoform, EVI1, encodes a 1,051-aa protein containing two DNA binding ZNF domains of seven and three motifs. The N-terminal ZNF domain binds to a GATA-like consensus motif (14), whereas the distal ZNF domain binds to an v-ets erythroblastosis virus E26 oncogene homolog (ETS)-like motif (15). EVI1Δ324 lacks ZNFs motifs 6 and 7, which prevents its binding to GATA-like sites.

Despite its discovery in 1988 (16, 17), very few EVI1 target genes have been identified, and most of these loci are known to be bound by EVI1 N-terminal ZNF domain (18–20). This lack of knowledge regarding the genes transcriptionally regulated by EVI1 has precluded a complete understanding of EVI1's role in development and cancer. In general, these biological processes are triggered by gene expression changes coordinated by a panel of TFs. We undertook to integrate EVI1 into these models through the identification of EVI1 target promoters and cooperating TFs. We first identified the EVI1 genomic occupancy in an ovarian carcinoma cell line. We then performed comparative analyses with expression datasets from clinical studies and cancer cell lines to characterize the genes regulated by EVI1 in epithelial cancer. Additional analyses provided comprehensive insights into EVI1's biological function in epithelial cancer progression through the transcriptional regulation of genes modulating cell proliferation, migration, adhesion, and apoptosis. In addition, through our search for other TF DNA binding motifs enriched near EVI1 ChIP-Seq peaks, we found that the AP1 DNA response element (TRE) colocalized with one-quarter of EVI1 ChIP-Seq peaks. Subsequent coimmunoprecipitations and cell-based assays identified a cooperative interaction between the AP1 family member FOS and EVI1 in cell proliferation, adhesion, and colony formation. Finally, genes with a linked EVI1/AP1 binding site in proximity are enriched in invasive ovarian carcinoma. These findings identify EVI1 as a multifunctional TF that synergizes with FOS in late-stage tumors.

Results

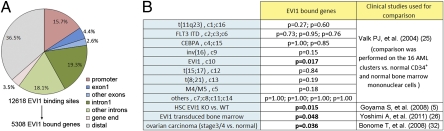

Because ChIP-Seq with human EVI1 antibodies would provide a mix of data representing the different MECOM isoforms, we expressed the most oncogenic isoform, EVI1, fused to a Flag-tag, in SKOV3 ovarian carcinoma cells (Fig. S1A). Subsequent ChIP-Seq of the Flag-EVI1 mildly expressed in SKOV3 cells identified 9,530,000 unique tags that mapped to the human genome. As expected, EVI1 was bound to the promoters of genes known to be EVI1 targets (Fig. S1B). For instance, Flag-EVI1 occupied the GATA2 (12, 20) 1S promoter similar to a previous report (21). We also found EVI1 binding sites at the FOS and JUN promoters (Fig. S1B), consistent with earlier data (19). ChIP-Seq data analysis (22), coupled with experimental validation (Fig. S1 C and D), identified 12,618 ChIP-Seq peaks of highest significance. Gene annotation (22) revealed a marked enrichment of peaks near transcription start sites (TSS) (Fig. S1E). A large proportion of peaks (15.7%) indeed fell within the promoters: exon1 (62.8% of exonic peaks) or intron1 (51.6% of intronic peaks) (Fig. 1A). A total of 5,308 EVI1-bound genes were identified in which the EVI1 peak was within a region of −10 kb from the TSS and +5 kb from the end of the gene.

Fig. 1.

Features of EVI1 binding sites. (A) Distribution of the 12,618 Flag-EVI1 enrichment peaks according to their location in promoters (−10 kb to the TSS), intragenic sites (+5 kb from the gene end), or distal sites (outside of these defined regions). (B) False discovery rate P values from GSEA indicating whether the EVI1-bound genes are significantly associated with the indicated gene expression profiles.

Although SKOV3 is not a myeloid leukemia cell line, we still expected that EVI1 would bind to some of its target genes found in myeloid disorders. We compared our EVI1-bound genes with lists of genes causally implicated in cancer from the Cancer Gene Census database (23) and found that myeloid leukemia genes were remarkably enriched (Dataset S1). This finding was not the case, however, for lymphoid leukemia genes (Fig. S1F), a disease in which EVI1 is not causally associated. Significant enrichment for myeloid leukemia genes (chronic: P = 0.042, acute: P = 0.050) was also found in the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway database (Dataset S1). We then used gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) to measure the association of EVI1-bound genes with various gene expression profiles from published clinical studies (Fig. 1B, Fig. S1G, and Dataset S1). Strikingly, among 16 clusters representing distinctive gene expression signatures identified from 285 acute myeloid leukemia patients (24), only one cluster, c10 (the only one linked to abnormal EVI1 expression), showed significant correlation with our EVI1 target genes (Fig. 1B). Moreover, GSEA revealed an enrichment of EVI1-bound genes in EVI1-transduced bone marrow cells (25) and the genes differentially expressed in WT hematopoietic stem cell (HSC)s vs. HSCs isolated from EVI1 KO mice (6). This finding is in line with previous reports of EVI1 molecular function in HSC renewal. Finally, we detected a marked association of EVI1-bound genes with the gene expression profiles generated from stage III/IV ovarian carcinoma samples vs. normal ovarian epithelium. Indeed, 38% (Fig. 1B and Dataset S1) of the genes differentially expressed in late-stage ovarian carcinoma were also occupied by EVI1. These findings are consistent with the known importance of EVI1 in HSC renewal, myeloid leukemia, and aggressive ovarian carcinoma.

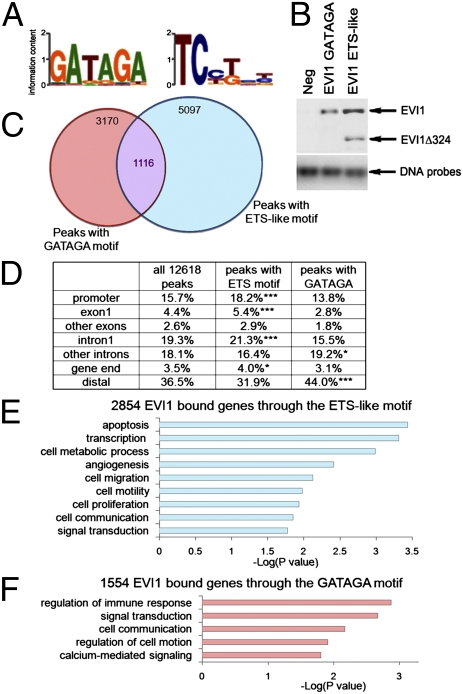

Previous studies have shown that the EVI1 N- and C-terminal ZNF domains recognize a GATA-like motif (12, 14, 20) and an ETS-like motif (15), respectively. Using de novo motif search, we identified GATAGA and ETS-like DNA binding motifs for EVI1 that represented its genome-wide occupancy (Fig. 2A). A modified in vitro binding assay (26) confirmed experimentally the association of endogenous EVI1 to DNA biotin-labeled probes carrying these refined motifs (Fig. 2B). Distribution calculations confirmed high occurrence for these motifs near EVI1 ChIP-Seq peaks (Fig. S2A). We also identified a tendency of mutual exclusivity for the occupancy pattern of the two EVI1 motifs, with only 8.8% (1,116 peaks) overlapping between ChIP-Seq peaks bearing ETS-like and GATAGA motifs (Fig. 2C and Dataset S1), significantly less than in corresponding random sites (16.3%, P < 0.0001). An increased fraction of ChIP-Seq peaks bearing an ETS-like motif was located near the TSS (Fig. 2D and Fig. S2). This finding is in contrast to the EVI1-occupied sites carrying a GATAGA motif, generally located farther from the TSS. Both EVI1-bound genes containing a GATAGA and ETS-like motif were significantly linked to the category pathways in cancer (P = 0.0099 and P = 0.0005, respectively; KEGG pathway). Therefore, both ZNF domains of EVI1 are likely to participate in EVI1 oncogenic functions. However, more precise gene ontology analysis highlighted some distinct specific biological features for these genes (Fig. 2 E and F).

Fig. 2.

Identification of two refined EVI1 DNA binding motifs and their localization at different sets of target genes. (A) Sequence logos best representing the EVI1 binding motifs for the N- (Left) and C-terminal (Right) ZNF domains. B, Upper is a Western blot analysis after pull down of biotin-labeled DNA probes incubated with SKOV3 nuclear lysates. The probes contained unrelated sequence (Neg) or the ETS-like and GATAGA EVI1 motifs that we identified. The starting DNA probe amount was run on an agarose gel (B, Lower). Because the N-terminal ZNF domain of EVI1 is disrupted in the EVI1Δ324 transcript, only the full-length form of EVI1 binds to the GATAGA motif, whereas both EVI1 and EVI1Δ324 proteins can bind to the ETS-like probe. (C) Representation of the overlap between the EVI1 peaks containing an ETS-like motif and a GATAGA motif. The overlap is about one-half less than expected by chance (P < 0.0001). (D) Table summarizing the location of Flag-EVI1 enrichment peaks containing either GATAGA (3,170 peaks) or ETS-like motifs (5,097 peaks). Promoters (−10 kb to the TSS), intragenic sites (+5 kb from gene ends), or distal sites are shown. Significant enrichments compared with the 12,618 dataset are indicated with asterisks (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001). (E and F) Functional classification clustering for biological processes using DAVID for the list of EVI1-bound genes associated with ChIP-Seq peaks carrying an ETS-like (E) or GATAGA (F) motif. The list of all 5,308 EVI1-bound genes was used as background.

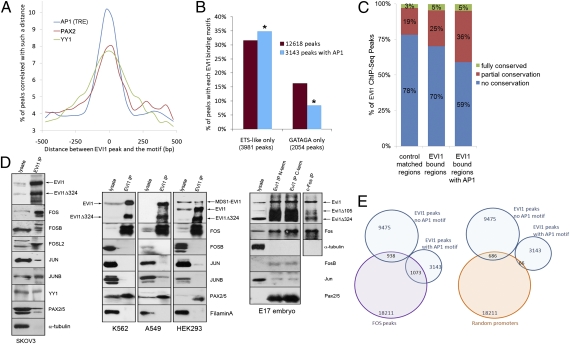

To identify possible new genomic-dependent cooperativity between EVI1 and other TFs, we scanned for the occurrence of 132 human TF DNA binding motifs (Jaspar database) at EVI1 ChIP-Seq peaks. This scan revealed significant (P < 0.0001) occurrence of 17 TF DNA binding motifs (Table S1). Two TFs previously reported as EVI1 interacting partners, GATA1 (27) and PU.1 (SPI1) (28), were among the overrepresented motifs. When we looked at the sequences of these 17 overrepresented TF motifs, we noticed that several were related to the EVI1 GATA or ETS-like motifs (Table S1). Therefore, the enrichment of these TF motifs at EVI1 ChIP-Seq peaks could simply be a consequence of this sequence relatedness. We, indeed, identified (by in vitro DNA binding assays) several motifs that EVI1 could bind physically (Fig. S3A). Although these data do not exclude the possibility that these co-occurrences are functionally important (i.e., GATA1 is a reported EVI1 interacting partner that shares a nearly identical DNA binding motif) (27), we decided to focus on the 10 TF motifs that failed to bind EVI1 directly. These TF motifs include AP1 TRE, PAX2, GABPA, TEAD, ELK1, MYF, CTCF, YY1, ELK4, and ARNT. The repartition of the distance between these 10 consensus motifs vs. the EVI1 ChIP-Seq peaks revealed that the AP1 TRE motif displayed the most significant enrichment in very close proximity of EVI1 peaks followed by PAX2 and YY1 (Fig. 3A and Fig. S3 B and C).

Fig. 3.

DNA binding motifs for three oncogenic TFs are overrepresented at EVI1 ChIP-Seq peaks. (A) AP1 (TRE), PAX2, and YY1 DNA binding motifs are highly overrepresented at EVI1 ChIP-Seq peaks. (B) Enrichment of peaks containing an EVI1 ETS-like motif (P = 9.6E−05) and depletion of peaks containing a GATAGA EVI1 motif were observed when an AP1 TRE is found within 250 bp of the peak. (C) Proportion of conserved EVI1-bound regions (±30 bp around peaks). The 12,618 EVI1 ChIP-Seq dataset, control-matched regions, and the 3,145 peaks bearing an AP1 motif within 250 bp are shown. The enrichment of conserved sequences in the EVI1/AP1-bound regions is highly significant (P ∼ 0). (D) Coimmunoprecipitation of the EVI1 endogenous protein from SKOV3, K562, A549, and HEK293 nuclear extracts and E17 mouse embryo lysate. Column 1 contains 5 μg nuclear proteins or 20 μg lysate from embryos. Column 2 was loaded with equal amounts of immunoprecipitation eluates. (E) Overlapping of EVI1 binding sites (middle of peaks ± 250 bp) with FOS ChIP-Seq peak regions (middle of peaks ± 250 bp; K562 cells, Gene Expression Omnibus GSM487426) or same-sized regions in random promoters (defined as −5 to +2 kb of genes).

The AP1 TF is a dimeric complex that assembles JUN, FOS, ATF, and MAF family members to form homo- or heterodimers. Specific dimers recognize and preferentially bind to different DNA sequence elements named TRE, cAMP response elements, MAF recognition elements, and antioxidant response elements (29). When we mapped these four different AP1 consensus motifs to the EVI1-occupied sites and corresponding random sites, we found a remarkable enrichment of 10.3-fold for the TRE consensus, whereas others were not enriched (Fig. S3D). Additional analysis revealed a strikingly large proportion (25.4%) of the EVI1-occupied sites that contained an exact AP1 TRE motif (Fig. S3E). These EVI1/AP1 TRE sites were preferentially located near genes and TSS (Fig. S3F), and they were markedly associated with an ETS-like motif rather than a GATAGA motif (Fig. 3B). We also identified a remarkable augmentation (P ∼ 0) of mammalian conservation at EVI1/AP1 TRE sites (Fig. 3C and Fig. S4A), suggesting the presence of a larger number of important regulatory elements in these regions.

The AP1 subunits that commonly associate with the AP1 TRE motif include the FOS and JUN family members. To determine if any of these subunits can form stable protein complexes with EVI1 and might, therefore, cooperatively bind DNA, we performed coimmunoprecipitation experiments with lysates of three human cancer cell lines (SKOV3, K562 chronic myeloid leukemia cells, and A549 alveolar basal carcinoma cells), E17 mouse embryos, and HEK293 embryonic kidney cells, all of which express endogenous EVI1 protein. We found a strong physical association between EVI1 and FOS, whereas the binding of EVI1 to other AP1 subunits was weaker and varied according to the tissue source (Fig. 3D). These results suggest a possible novel regulatory interaction between EVI1 and FOS. We also showed that PAX2 interacted with EVI1 in most tissues and that YY1 bound to EVI1 in SKOV3 cells. To further assess this regulatory interaction with FOS, we analyzed the overlap between EVI1 peak regions (SKOV3 cells) and FOS peak regions in K562 cells (30). Interestingly, 34.1% of EVI1 peaks with AP1 motif in proximity colocalized with FOS binding sites (P < 0.0001, χ2 test, compared with random promoters), whereas only 9.8% of EVI1 peaks with no AP1 motif were located within FOS-occupied regions (Fig. 3E). We also validated (by ChIP) the association of FOS protein to 21 EVI1/AP1-occupied sites (Fig. S4 B–D). Similar experiments with chromatin from SKOV3 cells knocked-down for EVI1 showed a strong tendency to weaken FOS occupancy. These results are consistent with the strong protein interaction that we observed between EVI1 and FOS (Fig. 3D), and they provide additional evidence for a regulatory interaction between EVI1 and FOS.

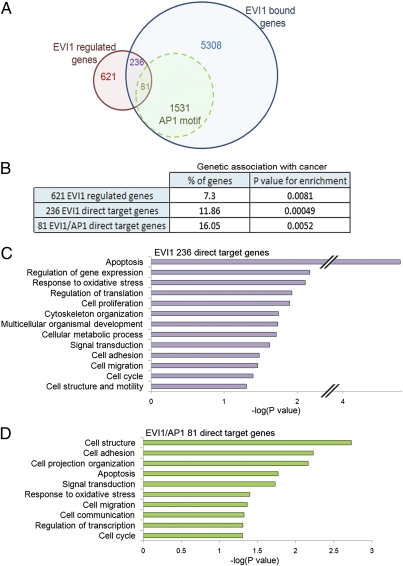

To identify genes directly regulated by EVI1 in epithelial cancer cells, we isolated RNA from untreated or EVI1 siRNA-treated SKOV3 cells. We also isolated RNA from HeLa cells, which do not express endogenous EVI1, and from HeLa cells transfected with Flag-EVI1 or Flag only plasmids (Fig. S4D). Using cDNA microarray GeneChips, we identified 621 genes differentially regulated by EVI1 in both cell lines (false discovery rate = 5%, P < 0.01) (Fig. 4A and Fig. S5A). A functional annotation analysis of the 621 genes highlighted 45 genes with known genetic associations with cancer (P = 0.0081) (Fig. 4B and Fig. S5B). Moreover, we detected by GSEA a correlation of EVI1-regulated genes with the gene expression profile of late-stage ovarian carcinoma (31) (P = 0.004) (Fig. S5C). Unlike the EVI1-bound genes, however, these 621 EVI1-regulated genes presented no significant link with myeloid leukemia. Among these 621 genes, 236 (38%, P = 0.0002) were also occupied by EVI1 and therefore, likely to represent functional direct EVI1 targets (Fig. 4A and Dataset S1). Greater than 62% of EVI1 direct target genes were associated with ChIP-Seq peaks containing an ETS-like motif (62.7%), whereas only 24.6% were linked to a GATAGA motif (Fig. S5D and Dataset S1). This finding suggests that the majority of the transcriptional regulation by EVI1 in these epithelial cancer cells occurs through the EVI1 C-terminal ZNF domain. An enriched fraction of the 236 EVI1-bound and -regulated genes had a linked EVI1/AP1 binding site (81 genes, 34.3%, P = 0.039) (Fig. 4A), suggesting an involvement of FOS in a direct coregulation of these genes. The subset of 236 genes also displayed a higher enrichment in genes genetically associated with cancer (Fig. 4B). EVI1 functions as a dual TF, because it associates with corepressors or coactivators (3). Our data confirm these findings, with 65% and 35% of the EVI1 direct target genes up- or down-regulated by EVI1, respectively (Fig. S5E).

Fig. 4.

Genes targeted and regulated by EVI1 explains its functions in adherent cells. (A) Overlap between EVI1-bound genes identified by ChIP-Seq and genes found to be differentially expressed by microarray experiments. The numbers of genes associated with an EVI1 ChIP-Seq peak bearing an AP1 motif at ±250 bp are labeled in green. (B) Percentages of EVI1-regulated genes that display a genetic association with cancer (DAVID Knowledgebase) and associated P values representing enrichments are shown for the indicated subgroups. (C and D) Gene ontology analyses using DAVID (GOTERM and PANTHER) of genes likely to be EVI1 direct targets (C) or EVI1 direct target genes whose peak(s) display an AP1 TRE motif at ±250 bp (D).

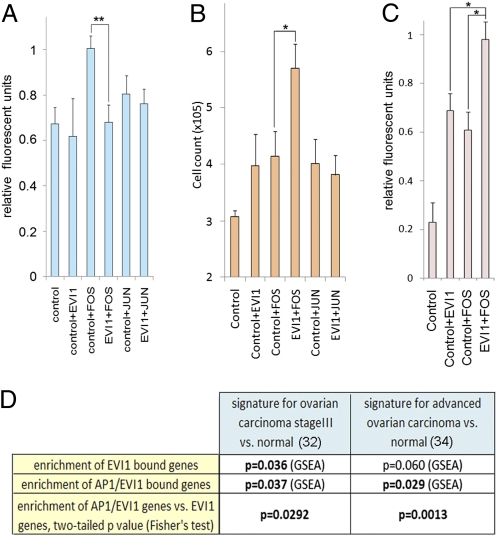

Three highly overrepresented categories found among the EVI1 direct target genes were regulators of gene expression, signal transduction, and organ development (Fig. 4C), consistent with EVI1's known function as a critical regulator of embryonic development (12, 32). We also found marked enrichment for genes controlling processes formerly associated with EVI1 (10, 12, 33), including apoptosis, cell proliferation, and migration. Interestingly, several potential biological functions were associated with EVI1 target genes, including cell adhesion, cell metabolism, response to oxidative stress, cell structure, and motility. All of these represent critical neoplastic features. To verify these findings in a physiological context, we used cell-based experiments. First, a scratch wound healing assay showed a dramatic reduction of passive cell locomotion when EVI1 protein levels were reduced (Fig. S6 A and B). Next, we expressed (in HeLa cells) suboptimal concentrations of EVI1, FOS, and JUN alone or in combination and then measured the effects on cell adhesion to fibronectin, cell proliferation, and colony formation. EVI1 could not modify endogenous HeLa cell adhesion, but it reduced adhesion triggered by FOS expression (Fig. 5A), suggesting that EVI1 is a negative regulator of FOS-induced cell adhesion. Moreover, although suboptimal levels of EVI1, FOS, and JUN elicited a moderate increase in cell proliferation, coexpression of FOS and EVI1 synergistically amplified HeLa cell number (Fig. 5B). In agreement with these results, anchorage-independent growth was potentiated by the coexpression of EVI1 and FOS (Fig. 5C). These data, supported by gene annotation analyses (Fig. 4D), indicate a functional cooperation between EVI1 and FOS to limit cell adhesion while enhancing cell proliferation, which are both hallmarks of invasive cancers. To confirm the synergy between EVI1 and FOS in advanced human tumors, we assessed (by GSEA) EVI1- and EVI1/AP1-bound gene enrichment in gene expression signatures defined from two different clinical studies (31, 34) on advanced papillary serous ovarian cancer. EVI1/AP1-bound genes were significantly associated with these gene profiles (Fig. 5D and Fig. S6 C and D). Moreover, the fraction of genes linked to a double EVI1/AP1 binding site was significantly enriched compared with all EVI1 bound genes. This finding suggests that EVI1 and FOS may cooperate to coregulate genes expressed in late-stage ovarian tumors.

Fig. 5.

EVI1 and FOS cooperatively regulate several biological processes in epithelial cells that confer an aggressive oncogenic phenotype. (A) EVI1 expression prevents FOS-induced cell adhesion to fibronectin. HeLa cells were transfected with a mixture of plasmids expressing Flag tag (control), Flag-EVI1 (EVI1), JUN, or FOS. The relative fluorescence of cells that have attached is measured. (B) Synergy between FOS and EVI1 in the induction of cancer cell growth. HeLa cells were transfected as indicated in A. The total cell number was counted 3 d later. (C) Synergy between FOS and EVI1 to accelerate anchorage-independent growth and resulting colonies formation. HeLa cells transfected as in B were grown in soft agar for 7 d. The final amount of cells was quantified by a fluorometric assay. (A–C) Mean ± SEM. *P values < 0.05, **P values < 0.01 (t test). (D) False discovery rate P values from GSEA using EVI1- or EVI1/AP1-bound genes and the gene expression profiles associated with late-stage ovarian carcinoma vs. normal tissue. Fisher test was used to calculate specific enrichment of AP1/EVI1-bound genes compared with all EVI1-bound genes within each expression signature.

Consistent with studies performed in murine cells (19), we identified an EVI1 enrichment peak in the FOS promoter (Fig. S1B). We also showed that FOS expression is differentially regulated by EVI1 in microarray experiments (Dataset S1). Last, we confirmed the transactivation of FOS expression by EVI1 in SKOV3 and HeLa cells using RT-quantitative-PCR (Fig. S7A) and immunoblotting (Fig. S7B). These data identify a feed-forward regulatory loop in which EVI1 directly modulates FOS expression and FOS and EVI1 cooperate in transcriptional programs to control at least two oncogenic functions: cell proliferation and adhesion (Fig. S7C).

Discussion

Although only a few EVI1 physiological target genes have been reported (33), our studies detected wide genomic occupancy in human ovarian carcinoma cells. EVI1 bound preferentially to promoters and genes, confirming that the main biochemical function of EVI1 is to regulate transcription through short-range effects. EVI1 is one of the few TFs known that contain two ZNF DNA binding domains. Our genome-wide data permitted important refinements for each DNA binding motif. We identified GATA and ETS-like motifs as previously reported; however, our motifs were shorter and better represented EVI1 genomic occupancy. The prominent trend for mutual exclusive DNA binding through EVI1 proximal and distal ZNF domains was consistent with previous in vitro studies (14). We, therefore, expected specific biological functions emerging from different sets of target genes regulated by each ZNF domain, similar to what has been observed for PAX6, whose two DNA binding domains act independently to regulate specific developmental functions (35). In support of this finding, we identified (by functional annotation) specific biological processes for EVI1 target genes associated with either the GATA or ETS-like motifs. Interestingly, we showed that ETS-like EVI1 target genes might regulate multiple aspects of tumorigenesis, such as angiogenesis, cell migration, and proliferation, that correspond to cell responses commonly modulated by ETS TFs (36). In our ovarian cancer model, the EVI1 ETS-like motif was represented more significantly than the GATAGA motif at EVI1 binding sites. Moreover, the EVI1 ChIP-Seq peaks bearing the ETS-like motif had a higher probability of being located in proximity to TSS and cancer gene loci and carrying an AP1 TRE motif. Before this study, only one EVI1 target gene had been identified that is regulated through the EVI1 ETS-like domain. Our study reveals the importance of this ETS-like domain in transcriptional regulation by EVI1.

The ETS family of TFs has been organized into four classes that reflect subtle differences in their DNA binding specificity (36). The EVI1 ETS-like motif that we identified resembles the class III SPI1 and SPIB DNA binding motif. SPI1 and SPIB consensus sequences were consistently enriched in the proximity of EVI1 binding sites, and in vitro binding assays showed that EVI1 could directly bind these class III motifs but not GABPA or ELK1 motifs, which belong to the ETS class I. EVI1, SPI1, and SPIB might, therefore, compete to occupy the same sites in chromatin.

Although accumulating evidence indicates that EVI1 is a crucial player in solid malignancies, there is limited mechanistic information on EVI1 oncogenicity in adherent cells. Our integrated genomics analyses have helped to elucidate the nature of EVI1 transcriptional activity in cancer cells. The remarkable enrichment of EVI1 direct target genes for most neoplastic functions suggests that EVI1 acts as a multitasking TF that modulates multiple processes, including cell migration, motility, adhesion, response to oxidative stress, proliferation, and apoptosis/survival. Several reports have shown that EVI1 acts as a proliferative agent that prohibits apoptotic stimuli, modulates cell cycle progression, or affects cellular growth response (13, 33, 37). However, little had been discovered about the regulatory mechanisms through which EVI1 affects theses features. Our studies, thus, provide valuable mechanistic insights into the nature of the genes regulated by EVI1.

We showed that EVI1 and FOS co-occupy sites in conserved regulatory elements. Gene ontology analysis provided evidence that FOS and EVI1 cooperate to regulate many of the properties normally associated with oncogenesis. We confirmed this finding experimentally by showing that EVI1 and FOS interacted to coregulate cellular growth, adhesion, and colony formation. Furthermore, we observed significant enrichment of the EVI1/AP1 gene subset in gene expression profiles linked to late-stage ovarian carcinoma phenotypes. EVI1 transactivates the Fos promoter in murine models (19), and our experiments also showed that EVI1 not only binds to the FOS promoter but also regulates FOS mRNA and protein levels in cancer cell lines. FOS is one of the main oncogenic components of the AP1 TF (38). EVI1 expression in cancer cells might serve to fully elicit FOS oncogenic potential through a feed-forward regulatory loop that drives neoplastic changes.

Materials and Methods

ChIP, ChIP-Seq, and Quantitative PCR.

Chromatin immunoprecipitations were performed using Dynabeads Protein G (Invitrogen), Flag M2 (Sigma), FOS K-25, and JUN H-79 antibodies (Santa Cruz). ChIP and input DNA were prepared into libraries and sequenced with the Illumina/Solexa platform (39). The sequencing data were mapped to the human reference genome (National Center for Biotechnology Information, v36, hg18), and peaks were called as described previously (22). Applied Biosystems 7500 and Power SYBR Green (Applied Biosystems) were used. Primers are listed in SI Materials and Methods.

Computational Analyses.

EVI1 de novo motif search was performed by selecting 100-bp sequences at 200 peaks of highest fold change located at ±10 kb of TSS. Weeder program identified a GATAGA motif. The sequences that carried this motif were excluded, and a second motif was found by Suite for Computational identification Of Promoter Elements. The scan of 132 TF binding motifs from Jaspar database was performed on 200-bp sequences at the 12,618 EVI1 enrichment peaks normalized with corresponding random sites using previously described methods (39, 40) with e-value cutoff of 0.001. Mapping of the exact AP1 consensus (TRE, CRE, ARE, and MARE) to 200-bp sequences at each of the 12,618 EVI1 binding sites and random sites was done with CisGenome. The identification of mammalian conservation at EVI1-bound sites or random sites was completed with CisGenome. P values were calculated using a binomial test unless otherwise stated. GSEA was performed with the top 500 (EVI1 ChIP-Seq genes by fold change) EVI1- or EVI1/AP1-bound genes using the preranked moderated t statistics obtained from Linear Models for Microarray Data analysis for the indicated microarray comparisons. False discovery rate P value < 0.05 was considered for statistic significance.

Gene annotation enrichment analyses for EVI1-bound or -regulated genes were completed with Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery Bioinformatics v6.7. The list of all human genes was used as default background unless otherwise stated.

Coimmunoprecipitations and Biotin-Labeled DNA Probe Binding Assays.

The EVI1 antibodies (Cell Signaling and gift from A. Perkins, University of Rochester, Rochester, NY) were captured on Dynabeads protein G (Invitrogen) before incubation with the cell nuclear or embryo lysates. The beads were washed before elution with SDS. Western blot analysis revealed the presence EVI1 interacting partners. Double strand biotin-labeled DNA probes encoding specific TF DNA binding motifs were captured onto streptavidin MyOne DynabeadsT1 (Invitrogen) before incubation with untransfected nuclear protein lysates. After pull down, immunoblotting analysis was performed to identify which TFs were attached to the DNA probes. This protocol was modified from the study by Mittler et al. (26).

Microarray Analyses.

SKOV3 cells were transfected with EVI1 siRNA (EVI1 ON-TARGETplus siRNA 8 and 10; Dharmacon) or microarray-suitable control siRNA (ON-TARGETplus Nontargeting Pool; Dharmacon). HeLa cells were transfected with Flag-EVI1– or Flag only-expressing plasmids. Total RNA was extracted 60 and 24 h later, respectively, and reverse transcribed. Human Gene 1.0 ST arrays (Affymetrix) were used to quantify the gene expression for four replicates of each condition. The statistical analysis was performed using Partek Genomics Suite (version 6.4).

Cell-Based Functional Assays.

Proliferation assays were carried out using HeLa cells transfected with the indicated plasmids in 24-well plates. The cells were counted 3 d after transfection with a Vi-CELL Cell Viability Analyzer. For adhesion assays, the cells were labeled with DiIC12 (3) Fluorescent Dye (BD Biosciences) to allow detection with a Tecan Safire microplate reader. The cell adhesion was determined by adding cells onto cold fibronectin-coated wells. After 30 min of incubation at 37 °C and washes, the relative fluorescence of cells that had attached was measured. The soft agar colony formation assay was performed using a Cytoselect 96-Well Cell Transformation Assay Kit (Cell Biolabs).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Archibald Perkins, University of Rochester, for sharing his mouse Evi1 antibodies. This work was supported by the Agency for Science, Technology, and Research (Singapore).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Data deposition: The data reported in this paper have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo (accession nos. GSE25210, GSE25212, and GSE25213).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1119229109/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Ogawa S, et al. Increased Evi-1 expression is frequently observed in blastic crisis of chronic myelocytic leukemia. Leukemia. 1996;10:788–794. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lugthart S, et al. High EVI1 levels predict adverse outcome in acute myeloid leukemia: Prevalence of EVI1 overexpression and chromosome 3q26 abnormalities underestimated. Blood. 2008;111:4329–4337. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-10-119230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goyama S, Kurokawa M. Pathogenetic significance of ecotropic viral integration site-1 in hematological malignancies. Cancer Sci. 2009;100:990–995. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2009.01152.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bei JX, et al. A genome-wide association study of nasopharyngeal carcinoma identifies three new susceptibility loci. Nat Genet. 2010;42:599–603. doi: 10.1038/ng.601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Choi YW, et al. Comparative genomic hybridization array analysis and real time PCR reveals genomic alterations in squamous cell carcinomas of the lung. Lung Cancer. 2007;55:43–51. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2006.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goyama S, et al. Evi-1 is a critical regulator for hematopoietic stem cells and transformed leukemic cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;3:207–220. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koos B, et al. The transcription factor Evi-1 is overexpressed, promotes proliferation and is prognostically unfavorable in infratentorial ependymomas. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:3631–3637. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-0175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Starr TK, et al. A transposon-based genetic screen in mice identifies genes altered in colorectal cancer. Science. 2009;323:1747–1750. doi: 10.1126/science.1163040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yokoi S, et al. TERC identified as a probable target within the 3q26 amplicon that is detected frequently in non-small cell lung cancers. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:4705–4713. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nanjundan M, et al. Amplification of MDS1/EVI1 and EVI1, located in the 3q26.2 amplicon, is associated with favorable patient prognosis in ovarian cancer. Cancer Res. 2007;67:3074–3084. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Osterberg L, et al. Potential predictive markers of chemotherapy resistance in stage III ovarian serous carcinomas. BMC Cancer. 2009;9:368. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-9-368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yuasa H, et al. Oncogenic transcription factor Evi1 regulates hematopoietic stem cell proliferation through GATA-2 expression. EMBO J. 2005;24:1976–1987. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nucifora G, Laricchia-Robbio L, Senyuk V. EVI1 and hematopoietic disorders: History and perspectives. Gene. 2006;368:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2005.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Delwel R, Funabiki T, Kreider BL, Morishita K, Ihle JN. Four of the seven zinc fingers of the Evi-1 myeloid-transforming gene are required for sequence-specific binding to GA(C/T)AAGA(T/C)AAGATAA. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:4291–4300. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.7.4291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Funabiki T, Kreider BL, Ihle JN. The carboxyl domain of zinc fingers of the Evi-1 myeloid transforming gene binds a consensus sequence of GAAGATGAG. Oncogene. 1994;9:1575–1581. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morishita K, et al. Retroviral activation of a novel gene encoding a zinc finger protein in IL-3-dependent myeloid leukemia cell lines. Cell. 1988;54:831–840. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(88)91175-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mucenski ML, et al. Identification of a common ecotropic viral integration site, Evi-1, in the DNA of AKXD murine myeloid tumors. Mol Cell Biol. 1988;8:301–308. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.1.301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Buonamici S, et al. EVI1 abrogates interferon-alpha response by selectively blocking PML induction. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:428–436. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410836200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tanaka T, et al. Evi-1 raises AP-1 activity and stimulates c-fos promoter transactivation with dependence on the second zinc finger domain. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:24020–24026. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yatsula B, et al. Identification of binding sites of EVI1 in mammalian cells. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:30712–30722. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504293200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shimanara A, Yamakawa N, Nishikata I, Morishita K. Acetylation of lysine564 adjacent to the CTBP-binding motif in EVI1 is crucial for transcriptional activation of GATA2. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:16967–16977. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.102046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen X, et al. Integration of external signaling pathways with the core transcriptional network in embryonic stem cells. Cell. 2008;133:1106–1117. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.04.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Futreal PA, et al. A census of human cancer genes. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:177–183. doi: 10.1038/nrc1299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Valk PJ, et al. Prognostically useful gene-expression profiles in acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1617–1628. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yoshimi A, et al. Evi1 represses PTEN expression and activates PI3K/AKT/mTOR via interactions with polycomb proteins. Blood. 2011;117:3617–3628. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-12-261602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mittler G, Butter F, Mann M. A SILAC-based DNA protein interaction screen that identifies candidate binding proteins to functional DNA elements. Genome Res. 2009;19:284–293. doi: 10.1101/gr.081711.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Laricchia-Robbio L, et al. Point mutations in two EVI1 Zn fingers abolish EVI1-GATA1 interaction and allow erythroid differentiation of murine bone marrow cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:7658–7666. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00363-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Laricchia-Robbio L, Premanand K, Rinaldi CR, Nucifora G. EVI1 Impairs myelopoiesis by deregulation of PU.1 function. Cancer Res. 2009;69:1633–1642. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eferl R, Wagner EF. AP-1: A double-edged sword in tumorigenesis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:859–868. doi: 10.1038/nrc1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Raha D, et al. Close association of RNA polymerase II and many transcription factors with Pol III genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:3639–3644. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911315106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bonome T, et al. A gene signature predicting for survival in suboptimally debulked patients with ovarian cancer. Cancer Res. 2008;68:5478–5486. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hoyt PR, et al. The Evi1 proto-oncogene is required at midgestation for neural, heart, and paraxial mesenchyme development. Mech Dev. 1997;65:55–70. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(97)00057-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wieser R. The oncogene and developmental regulator EVI1: Expression, biochemical properties, and biological functions. Gene. 2007;396:346–357. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2007.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mok SC, et al. A gene signature predictive for outcome in advanced ovarian cancer identifies a survival factor: Microfibril-associated glycoprotein 2. Cancer Cell. 2009;16:521–532. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Verbruggen V, et al. The Pax6b homeodomain is dispensable for pancreatic endocrine cell differentiation in zebrafish. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:13863–13873. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.108019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wei GH, et al. Genome-wide analysis of ETS-family DNA-binding in vitro and in vivo. EMBO J. 2010;29:2147–2160. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mitani K. Molecular mechanisms of leukemogenesis by AML1/EVI-1. Oncogene. 2004;23:4263–4269. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jochum W, Passegué E, Wagner EF. AP-1 in mouse development and tumorigenesis. Oncogene. 2001;20:2401–2412. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kunarso G, et al. Transposable elements have rewired the core regulatory network of human embryonic stem cells. Nat Genet. 2010;42:631–634. doi: 10.1038/ng.600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lin CY, et al. Whole-genome cartography of estrogen receptor alpha binding sites. PLoS Genet. 2007;3:e87. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.