Abstract

Slow relaxation occurs in many physical and biological systems. “Creep” is an example from everyday life. When stretching a rubber band, for example, the recovery to its equilibrium length is not, as one might think, exponential: The relaxation is slow, in many cases logarithmic, and can still be observed after many hours. The form of the relaxation also depends on the duration of the stretching, the “waiting time.” This ubiquitous phenomenon is called aging, and is abundant both in natural and technological applications. Here, we suggest a general mechanism for slow relaxations and aging, which predicts logarithmic relaxations, and a particular aging dependence on the waiting time. We demonstrate the generality of the approach by comparing our predictions to experimental data on a diverse range of physical phenomena, from conductance in granular metals to disordered insulators and dirty semiconductors, to the low temperature dielectric properties of glasses.

Keywords: nonequilibrium, slow dynamics, memory effects, 1/f noise

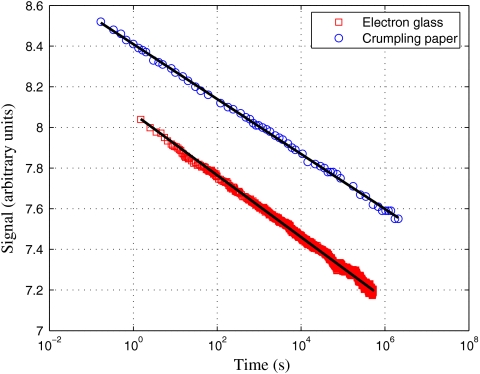

Physicists often take for granted that systems relax exponentially. Indeed, when a capacitor discharges, it will discharge exponentially, with a rate independent of the time it has been charged for. However, the relaxation of many systems in nature is far from exponential, as was noticed already in the 19th century by Weber (1). In many cases, the relaxation is logarithmic: Such relaxations have been experimentally observed in the decay of current in superconductors (2), current relaxation in metal-oxide-semiconductor field-effect transistor devices (3), mechanical relaxation of plant roots (4), volume relaxation of crumpling paper (5), and frictional strength (6), to name but a few. Fig. 1 shows experimental data for electron glasses and for crumpling a thin sheet, which are governed by extremely different physical processes, yet they display identical relaxation behavior, which is logarithmic over a strikingly broad time window.

Fig. 1.

Experimental results showing a logarithmic relaxation in the electron glass indium oxide, where conductance is measured, and in a system of crumpling mylar, where the height is measured, after a sudden change in the experimental conditions. As seen in the graph, the logarithmic change in the physical observable can be measured from times of order of seconds or less to several days (5, 26). Similar logarithmic relaxations, observed over many decades in time, occur in numerous physical systems, ranging from currents in superconductors to frictional systems. Data courtesy of Z. Ovadyahu and S. Nagel.

In these systems, in contrast to the capacitor example, the relaxation does depend on the time the system has been perturbed for—in the scientific jargon, this is referred to as “aging.” In fact, slow relaxations and aging are amongst the most distinct features of glasses, whose understanding presents an important problem in contemporary condensed matter physics. Much experimental and theoretical attention has been devoted to aging in the past decades, in a variety of fields, such as spin-glass (7–13), colloids (14, 15), vortices in superconductors (16, 17), and many others (18–23).

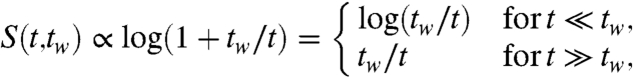

Here, we study a generic model for aging and discuss several mechanisms yielding a broad distribution of relaxation rates. We demonstrate the generality of the model on four different experimental systems, measuring the dependence of the relaxation both on time t and on the “waiting time” tw, during which an external perturbation has been applied. We show how the following form of relaxations transpires:

|

[1] |

where S is the physical observable. This means that the initial relaxation, at times short compared with tw, is logarithmic, whereas at long times compared to tw it falls off as the inverse of the time—a power-law decay, much slower than exponential or stretched exponential decay; this is reminiscent of, but not equivalent to, the result of ref. 24.

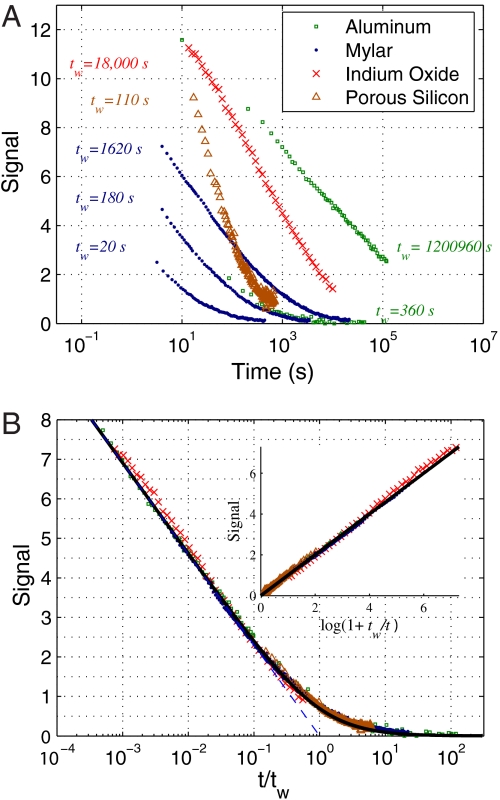

Fig. 2 shows the excellent agreement between this prediction and experimental results for four different systems, measuring various physical observables: conductance relaxation in the electron glasses indium oxide and granular aluminum (25–34), relaxation of the dielectric constant in the plastic mylar (35–37), and conductance relaxation in room temperature porous silicon (38, 39). The experiments also markedly differ in the involved timescales. Details of the experiments are given in Table 1.

Fig. 2.

(A) Results of aging experiments for four different systems measuring different physical observables. Experimental parameters can be found in Table 1. The x axis denotes the time (on logarithmic scale, spanning five decades in time, from seconds to days), and the y axis denotes the signal (with different units for each dataset). (B) The x coordinate of each dataset is scaled according to the known waiting time tw, and the y coordinate is scaled such that the signal at t = tw is log(2) (for convenience). The data collapses onto a single curve, which is compared to the theoretical prediction of Eq. 1. The Inset shows the same data has indeed linear dependence when the x axis is defined according to Eq. 1.

Table 1.

Details of experiments

| System | Measured variable | Units | tw, s | Source |

| Aluminum | conductance (σ) | 0.02δσ/σ | 1,200,960; 360 | Grenet et al., ref. 32 (2007) |

| Mylar | dielectric constant (ϵ) | 10-6δϵ/ϵ | 18,000 | Ludwig et al., ref. 35 (2003) |

| Indium oxide | conductance (σ) | 0.01δσ/σ | 20; 180; 1,620 | Ovadyahu, ref. 28 (2006) |

| Porous silicon | conductance (σ) | 0.02δσ/σ | 110 | S. Borini, personal communication (2010) |

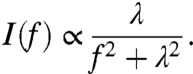

In the following, we describe the aging protocol used in the experiments, and introduce a model that predicts Eq. 1. We explain how one can understand the slow relaxations in terms of an underlying distribution of relaxation rates of a particular form:

| [2] |

which we shall show can emerge due to various, physically distinct, mechanisms: thermal activation, quantum mechanical tunneling, or through a third mechanism relying on a multiplicative process. We then proceed to describe the connection to the ubiquitous 1/f noise encountered in many systems, as well as the possible role of the distribution described in Eq. 2 in other intriguing phenomena such as Benford’s law (40).

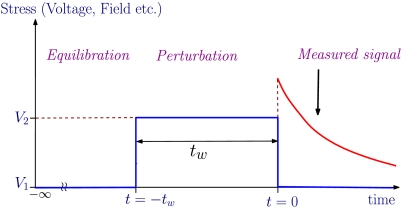

The Experimental Protocol

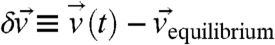

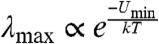

The aging protocol is illustrated in Fig. 3. Its first step consists of letting the system attempt to equilibrate for a relatively long time (typically of the order of hours or days). Next, one perturbs the system, in a way that depends on the experimental system: For indium oxide and aluminum, this is done by changing the voltage of a capacitively coupled gate; for the mylar sample, it is done by putting the system in a perpendicular electric field; whereas for porous silicon, a large bias voltage is applied. The perturbation is now maintained for a time tw. After it is switched off, the physical observable is continuously monitored, as it relaxes. The longer tw is, the slower the resulting relaxation.

Fig. 3.

Schematic description of the different stages of the aging protocol. At time t = -tw a perturbation is applied to the system, which is turned off at time t = 0. We will be interested in the form of the relaxation of the physical observable in the last stage.

The Model

Having laid out a concrete experimental protocol, we are now well positioned to describe a generic model that will yield the form of aging described by Eq. 1. The model will involve two ingredients: First, the understanding that a broad distribution of relaxation rates λ occurs whose logarithm is approximately uniformly distributed over some broad range, as described by Eq. 2. The second ingredient involves understanding what this relaxation rate distribution implies on the relaxations, within the aging protocol.

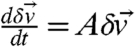

The model assumes that the measured physical observable (conductance, dielectric constant, etc.) is affected by an ensemble of modes, which are independent and contribute to the observable in a definite way (for example, a relaxation of any of the modes will cause the conduction to decrease). For each particular system under study, understanding the microscopic source of these modes is a quite different sort of question one may ask, and is outside the scope discussed here (see ref. 34 for a discussion on these assumptions regarding the modes in the context of electron glasses). In general, these assumptions would make sense for a physical observable that depends on the configuration of the whole system (e.g., conductance, volume) and not some local probe (e.g., current measured in a scanning tunneling microscope tip). Also, we would always be assuming that a large number of these modes contribute, so that we can take the continuous limit, and discuss probability distributions. Presumably, the model would fail for a sufficiently small sample [although, in the case of electron glasses, the logarithmic relaxations were experimentally observed even for micron sized samples (41)]. Each of the modes would relax exponentially to its equilibrium, but with a different relaxation rate. To support these assumptions, one may think of the system as being formally characterized by a state vector  , containing all the relevant information determining the physical observable. Perturbing the system weakly near its equilibrium, one can always linearize the equations of motion, and obtain an equation

, containing all the relevant information determining the physical observable. Perturbing the system weakly near its equilibrium, one can always linearize the equations of motion, and obtain an equation  , with

, with  , and A a matrix, independent of time. The real part of the eigenvalues of A must be negative, in order for the equilibrium to be stable, and they have the physical meaning of relaxation rates: As is seen by solving the linear equation, each eigenmode relaxes exponentially to zero, independently of the other eigenmodes. In certain cases (29), the form of A can be worked out explicitly.

, and A a matrix, independent of time. The real part of the eigenvalues of A must be negative, in order for the equilibrium to be stable, and they have the physical meaning of relaxation rates: As is seen by solving the linear equation, each eigenmode relaxes exponentially to zero, independently of the other eigenmodes. In certain cases (29), the form of A can be worked out explicitly.

We shall now explain three different mechanisms that lead to an abundance of slowly relaxing modes of the system, described mathematically by Eq. 2. Using our assumption that the modes contribute positively and uniformly to the measured physical observable, the superposition of these modes will yield (in a certain time window, the conditions of which we will discuss) the logarithmic relaxations described earlier.

Thermal Activation.

A diversity of physical processes are governed by thermal activation, which is perhaps the simplest physical mechanism that can give rise to Eq. 2, as has been known for a long time (19, 42, 43). We should have in mind a rugged energy landscape characterizing the system, with many local minima. At a given time, we can denote by  the vector of probabilities for the system to reside in each of the minima. Clearly, for a system governed by stochastic dynamics, the probability vector would obey the same linear equation mentioned earlier; namely,

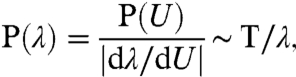

the vector of probabilities for the system to reside in each of the minima. Clearly, for a system governed by stochastic dynamics, the probability vector would obey the same linear equation mentioned earlier; namely,  (i.e., we have defined a Markov process). The relaxation modes in this case approximately correspond to crossing one of the energetic barriers connecting two of the local minima. Here, the rate λ of a given process is given by the Arrhenius formula; namely, it is exponential in the energetic barrier U; namely, λ ∝ e-U/kT, which the system has to cross in order to reduce its energy. We will associate each mode with one such transition (across an energetic barrier U) and assume that the size of these barriers is distributed smoothly over a certain range of energies. We can now readily calculate the resulting relaxation rate distribution:

(i.e., we have defined a Markov process). The relaxation modes in this case approximately correspond to crossing one of the energetic barriers connecting two of the local minima. Here, the rate λ of a given process is given by the Arrhenius formula; namely, it is exponential in the energetic barrier U; namely, λ ∝ e-U/kT, which the system has to cross in order to reduce its energy. We will associate each mode with one such transition (across an energetic barrier U) and assume that the size of these barriers is distributed smoothly over a certain range of energies. We can now readily calculate the resulting relaxation rate distribution:

|

[3] |

where we have taken P(U) as approximately constant. For isothermal processes, the temperature dependence entering the proportionality constant does not play a role in the aging behavior. From this formula, we can also deduce the smallest and largest rates the system supports (corresponding to the fastest and slowest times): These are  and

and  , related to the extremal barrier heights. Note that, due to the exponential dependance on U, even a small range of energy barriers can result in a broad range of relaxation rates. The above mechanism is essentially the same leading to 1/f noise (44, 45) and is reminiscent of Bouchaud’s trap model (19).

, related to the extremal barrier heights. Note that, due to the exponential dependance on U, even a small range of energy barriers can result in a broad range of relaxation rates. The above mechanism is essentially the same leading to 1/f noise (44, 45) and is reminiscent of Bouchaud’s trap model (19).

It should be emphasized that we have assumed here that the energy barriers vary sufficiently slowly, and therefore their variation within the energy interval [Umin,Umax] can be neglected. This simple picture turns out to be extremely successful when applied to recent experiments on porous silicon performed around room temperature. At such a high temperature, thermal effects are expected to be dominant over quantum effects, and indeed the maximal timescale λmax was found experimentally to be very sensitive to temperature, as expected from the above formula (39).

However, it is experimentally found that in various systems the relaxations are insensitive to temperature (32), which necessitates a different mechanism. Quantum tunneling is the second mechanism that yields Eq. 2.

Quantum Mechanical Tunneling.

Let us keep in mind the picture described earlier for the rugged energy landscape, but now assume that we are at low enough temperatures such that thermal activation across the barriers is prohibited. The system will be able to quantum mechanically tunnel through the barriers, paying a penalty that is typically exponentially suppressed with the distance. Thus, for this process as well, the rate λ depends exponentially on a smoothly distributed variable, which in this instance is the distance: λ ∼ e-2r/ξ, with ξ the localization length of the wavefunctions, and r the spatial distance between the two points. In a recent work (46), the distribution of relaxation rates was calculated for this case, taking into account the correlations that exist (the distances are not independent in this case). It was found that one still obtains the 1/λ distribution, albeit with small but interesting logarithmic corrections. Here, the role played by the temperature T in Eq. 3 is played by the localization length ξ. Related considerations for a varying height of the barrier through which the tunneling occurs are given in ref. 47.

In both cases, of thermal activation and of quantum mechanical tunneling, we would like the barrier distribution to be broad in energy or real space; namely, it should be large compared to the energy kT or the localization length ξ, respectively, in order to achieve a broad range of relaxation rates.

So far, we discussed two different natural ways that lead to this broad distribution of relaxation rates; namely, thermal activation (19, 42, 43) and quantum tunneling (46). The exponential nature of these processes is the key ingredient in obtaining Eq. 2. Both mechanisms, however, are inadequate to describe the logarithmic relaxation in crumpling paper, for example (5). We shall now present another mechanism, which does not rely on a variable being exponential, but rather, on the central-limit theorem. This suggests the mechanism should be broadly applicable. We will show how the interplay of many random processes can, under general conditions, lead to a log-normal distribution, which is well approximated over a broad range by Eq. 2.

Multiplicative Processes.

In many physical examples, an observable depends on the product of many approximately independent variables, which is referred to as a multiplicative process. Understanding the importance of such processes in nature dates back (at least) to Shockley (48), who discussed the connection of multiplicative processes to log-normal distribution that we shall also utilize here. See ref. 49 for a strongly related discussion in the context of 1/f noise.

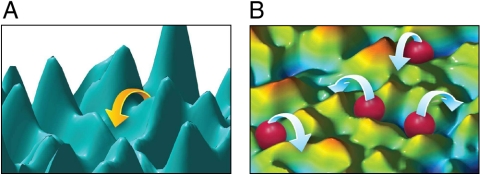

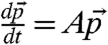

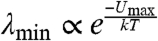

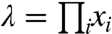

An example of a multiplicative process is the transmission of a particle through a one-dimensional disordered wire: If we divide the wire into a large number of segments, it is known that the average transmission is the product of the individual transmissions through each segment (50). Fig. 4 demonstrates pictorially another such example; namely, how for electron glasses relaxation can occur via the simultaneous tunneling of various electrons, which is also approximately a multiplicative process. If we assume that the relaxation rate λ is a product of many independent variables xi, we can readily calculate the resulting distribution of relaxation rates. Because  , we have, using the central-limit theorem,

, we have, using the central-limit theorem,

| [4] |

By changing back to the variable λ, we find that it follows a log-normal distribution:

| [5] |

where t0 is a constant with the dimensions of time. Far from the tails of the distribution (namely, when | log(λt0)| ≪ Δ), the distribution reduces to Eq. 2. Remarkably, in the crumpling paper example, the distribution of the lengths of the segments was measured directly, and shown to follow a log-normal distribution (51). The compatibility of log-normal distribution and logarithmic relaxations fits well with the theoretical framework we suggest.

Fig. 4.

Pictorial demonstration of different physical mechanisms leading to a broad distribution of relaxation rates. (A) The energy landscape of various complex systems, including glasses, contains many minima. The energetic barriers separating them are smoothly distributed over a certain range. In order for the system to relax its energy, it must cross these barriers by thermal activation or by quantum mechanical tunneling: Both are exponential in the barrier, which lead to a rate distribution described by P(λ) ∼ 1/λ, as we discuss in detail. (B) Many particle transitions in an electron glass are an example of a multiplicative process: In many electronic configurations, moving any single electron in the system to one of the vacant sites will result in higher energy, and therefore these processes will not occur at low enough temperatures. However, changing the position of a larger number of electrons can result in a lower energy. The rates of this process can be approximately written as a product of the rates of the single particle processes involved, leading to a rate distribution described by a log-normal distribution.

We shall now discuss the implications of this distribution on aging experiments, showing it leads to aging of a particular form, called “full” aging, in a particular limit. This was done in the context of relaxation in electron glasses in (33). The derivation we will present, however, does not rely on any peculiar properties of this specific system, and as such will be broadly applicable for all physical systems that follow the 1/λ distribution.

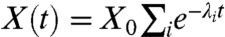

Let us assume that the system supports i = 1…N≫1 relaxation modes, with corresponding relaxation rates λi, each of which contributes an amount X0 to the physical observable (e.g., conductance or dielectric constant). Before going to the more involved aging experiment, let us consider the case where we excite all of these modes by some uniform amplitude. The physical observable X measured a time t after the perturbation, would read  , which in the continuous limit goes to

, which in the continuous limit goes to

|

[6] |

where P(λ) is the distribution of relaxation rates. In the case where P(λ) ∼ 1/λ, introduced earlier, with λmin and λmax the lower and upper cutoffs, we obtain the difference of two exponential integral function (33, 52):

| [7] |

For the case where the involved times are much smaller than the reciprocal lower cutoff λmin, and much larger than the reciprocal upper cutoff, the equation reduces to a simpler form:

| [8] |

Thus, we expect a logarithmic relaxation, which is indeed experimentally observed in a large variety of systems, as discussed earlier. Fig. 1 shows such a logarithmic relaxation, measured in an indium oxide sample.

Going on to the aging protocol, we shall assume that the perturbation is small enough such that the rates of the relaxing modes are indifferent to it. Nonetheless, upon the application of the perturbation, the fixed point to which the system attempts to relax (which does not have to be the true equilibrium, but can be a metastable state) is different when the perturbation is applied. Therefore, during the second stage of the experiment (see Fig. 4), the system relaxes toward the new metastable state, which means that the relaxation modes are excited with respect to the original metastable state: Relaxation to the new metastable state implies excitation with respect to the old one. The closer we get to the new minimum, the further we are from the initial one.

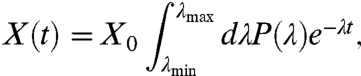

Let us illustrate this for the example of a single relaxation mode: In this case the relaxation is exponential, and therefore at the moment when the perturbation is switched off the distance from the new metastable state is proportional to e-λtw. At this moment the distance from the original metastable state is 1 - e-λtw; indeed, for tw = 0 nothing happens, whereas for tw → ∞ the largest possible excitation occurs. A time t later, the amplitude of the relaxation mode, which decays exponentially, would therefore be (1 - e-λtw)e-λt. Generalizing this for the case of many relaxation modes, we find that a time t after the perturbation has been switched off, the physical observable is given by

|

[9] |

This can be written, as before, in terms of exponential integral function. Assuming that we are in the regime of intermediate asymptotics, where the experimental timescales are much larger than the reciprocal upper cutoff and much smaller than the reciprocal lower cutoff, we obtain the difference of two logarithms:

| [10] |

leading to Eq. 1.

It should be noted that the regime where the experimental time is comparable to 1/λmin can also be reached, and it was shown that Eq. 9 accounts of the aging behavior in porous silicon also in the case where significant deviations from the full aging regime were observed (39). In other words, the model predicts full aging only in the asymptotic regime, and can also account for the deviations from full aging. Related system dependent cutoffs were also discussed in the context of spin-glass (27).

Connection to 1/f Noise

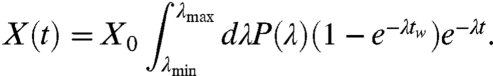

The broad underlying distribution of relaxation rates, which played a crucial role in determining the slow relaxations, is also central for understanding low-frequency noise in many systems. A variety of physical, biological, and financial models show a universal form of low-frequency noise (44, 45, 49, 53), with a power-spectrum scaling as 1/f. This ubiquitous form of noise is deeply related to the logarithmic relaxation that we study here, the underlying principle being a roughly uniform distribution of effective barriers. In ref. 54, a relation between the two physical phenomena was made, based on a theory devised by Onsager nearly a century ago: The connection is made through the Onsager’s regression principle, stating that the relaxation of a system close to its equilibrium is related to the spectrum of the fluctuations of the system around the equilibrium (55). Each mode with a rate λ generates a Lorentzian noise spectrum (42, 43):

|

[11] |

Summing over many modes using the distribution of Eq. 2 yields 1/f noise. Linking these two seemingly unrelated universal behaviors, logarithmic relaxations and 1/f noise, seems to us both conceptually appealing and of practical importance. For one, it means that the different physical mechanisms we suggested to yield the broad distribution of relaxation rates would also imply 1/f noise.

Other Appearances of the 1/λ Distribution in Nature

In fact, the P(λ) ∼ 1/λ distribution, which plays a pivotal role in determining the aging, logarithmic relaxations, and 1/f noise, appears also in completely different contexts. The Gutenberg–Richter law (56), for example, states that the distribution of the magnitude of earthquake is a power law. The exponent is experimentally found, in various methods of analysis, to be close to one (57). Another striking example lies in the so-called “first-digit problem.”

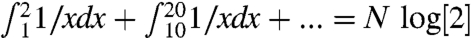

Toward the end of the 19th century, the astronomer Simon Newcomb noticed, while looking at his logarithm table, that numbers starting with 1 are looked up far more often than higher digits (58). Half a century later, the physicist Frank Benford rediscovered the phenomenon, and asked himself the following question: What is the distribution of the leading digits of numbers encountered in a certain scenario? (40). Remarkably, in hugely differing datasets such as those found in tax returns, tables of physical constants, birth rates, and many others, the relative occupance of each digit follows a universal (and nonuniform) distribution: P(d) = log(1 + 1/d), where d is the digit. This is known as Benford’s law, and it is robust enough to be used to detect frauds in tax returns (59). It can be explained in a simple way, if we assume that the distribution of x, the variable measured, follows approximately P(x) ∼ 1/x, over a large window. Clearly, the probability that the first digit is 1 is proportional to  , where N is the number of decades spanned by the distribution (assumed to be a large number). Similarly for the digit d, one obtains N log[(d + 1)/d], yielding Benford’s law. Thus, there is an intimate relation between the 1/x distribution leading to logarithmic, slow relaxations, and Benford’s law, stating universal statistics in the first-digit problem. It remains a challenge to find the unifying mechanisms between these various observations.

, where N is the number of decades spanned by the distribution (assumed to be a large number). Similarly for the digit d, one obtains N log[(d + 1)/d], yielding Benford’s law. Thus, there is an intimate relation between the 1/x distribution leading to logarithmic, slow relaxations, and Benford’s law, stating universal statistics in the first-digit problem. It remains a challenge to find the unifying mechanisms between these various observations.

The Extent of Applicability of the Theory

So far, we have discussed three different physical mechanisms leading to the same aging behavior. There are, of course, other forms of slow relaxations in nature, which are also commonly observed, and many fascinating physical systems that do not fit into the framework outlined here. Two important examples are the aging behavior of spin-glass systems, which appears to be more complex (7–9) and is not described by this model, and the behavior of molecular and colloidal glasses, which have received much attention in recent years (14, 15). As indicated by refs. 60 and 61, the model proposed here is not consistent with the relaxations observed in these systems. Another generic form of slow relaxations in nature is stretched exponential relaxation e-(t/τ)β, which has been experimentally observed in various systems (1, 16, 62–64), and for which several theoretical models have been proposed (65–68). For small β, this form is similar to Eq. 1, but it is still possible to distinguish the two, by analyzing the short-time behavior, where a power law markedly differs from a logarithm. It would be interesting to make a better classification of these two universality classes (and possibly others), and to determine the extent and limitations of the applicability of each of them, but this task is beyond the scope of this work.

Conclusions

To summarize, in this paper we discussed a generic model for slow relaxations and aging, whose signature is a distinct crossover from a logarithm to a power law, with no fitting parameters other than the overall scaling. Theoretically, we have shown how various different physical mechanisms give rise to a broad distribution of relaxation rates, of a particular form, and analyzed the resulting aging behavior. The data from various experiments was shown to agree well with this prediction, over many decades in time. The experiments measure different physical observables, in a variety of systems and temperatures. This form of aging is fundamentally connected to other phenomena that are commonly observed in nature, such as 1/f noise. Part of the beauty of physics lies in the surprising connections it offers, between different fields and phenomena. We showed that one could understand on equal footing the aging of quantum tunneling in electron glasses (33) and the mechanical relaxations of plant roots (4), and that both are connected to the 1/f noise electrical engineers are well familiar with. As such, we believe the model presented can serve as a paradigm for slow relaxations and aging for a broad class of systems.

Acknowledgments.

We thank S. Borini, J. Delayhe , T. Grenet, S. Nagel, and Z. Ovadyahu for important discussions and for their experimental data, and J. Langer, A. Hebard, and J. P. Bouchaud for useful comments. This work was supported by a Deutsch-Israelische Projektkooperation grant as well as by Israel Science Foundation and Binational Science Foundation grants and the Center of Excellence Program. The research of Y.I. was supported by a Humboldt extension grant.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare no conflict of interest (such as defined by PNAS policy).

This contribution is part of the special series of Inaugural Articles by members of the National Academy of Sciences elected in 2008.

References

- 1.Weber W. Uber die elasticity der seidefaden. Ann Phys. 1835;34:247–257. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gurevich A, Küpfer H. Time scales of the flux creep in superconductors. Phys Rev B Condens Matter. 1993;48:6477–6487. doi: 10.1103/physrevb.48.6477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Woltjer R, Hamada A, Takeda E. Time dependence of p-mosfet hot-carrier degradation measured and interpreted consistently over ten orders of magnitude. IEEE Trans Electron Devices. 1993;40:392–401. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Büntemeyer K, Lüthen H, Büttger M. Auxin-induced changes in cell wall extensibility of maize roots. Planta. 1998;204:515–519. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Matan K, Williams RB, Witten TA, Nagel SR. Crumpling a thin sheet. Phys Rev Lett. 2002;88:076101. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.88.076101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ben-David O, Rubinstein SM, Fineberg J. Slip-stick and the evolution of frictional strength. Nature. 2010;463:76–79. doi: 10.1038/nature08676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dupuis V, et al. Aging, rejuvenation and memory phenomena in spin glasses. Pramana. 2005;64:1109–1119. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bouchaud JP, Cugliandolo L, Kurchan J, Mezard M. Out of equilibrium dynamics in spin-glasses and other glassy systems. In: Young AP, editor. Spin Glasses and Random Fields. Singapore: World Scientific; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Castillo HE, Chamon C, Cugliandolo LF, Kennett MP. Heterogeneous aging in spin glasses. Phys Rev Lett. 2002;88:237201. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.88.237201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cugliandolo L, Kurchan J. Analytical solution of the off-equilibrium dynamics of a long-range spin-glass model. Phys Rev Lett. 1993;71:173–176. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.71.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cugliandolo L, Kurchan J, Ritort F. Evidence of aging in spin-glass mean-field models. Phys Rev B Condens Matter. 1994;49:6331–6334. doi: 10.1103/physrevb.49.6331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fischer K, Hertz J. Spin glasses. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marinari E, Parisi G, Rossetti D. Numerical simulations of the dynamical behavior of the SK model. Eur Phys J B. 1998;2:495–500. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berthier L, Biroli G, Bouchaud JP, Cipelletti L, van Saarloos W. Dynamical Heterogeneities in Glasses, Colloids, and Granular Media. Oxford: Oxford Univ Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cipelletti L, Weeks ER. Glassy dynamics and dynamical heterogeneity in colloids. 2010 arXiv:1009.6089. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Du X, Li G, Andrei EY, Greenblatt M, Shuk P. Ageing memory and glassiness of a driven vortex system. Nat Phys. 2011;3:111–114. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pleimling M, Täuber UC. Relaxation and glassy dynamics in disordered type-ii superconductors. Phys Rev B Condens Matter. 2011;84:174509. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sibani P, Hoffmann K. Hierarchical models for aging and relaxation of spin glasses. Phys Rev Lett. 1989;63:2853–2856. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.63.2853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bouchaud JP. Weak ergodicity breaking and aging in disordered systems. J Phys I France. 1992;2:1705–1713. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bouchaud JP. Aging in glassy systems. In: Cates M, Evans M, editors. Soft and Fragile Matter. Bristol, UK: Institute of Physics Publishing; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Henkel MP, Sanctuary R. Lecture Notes in Physics. Oxford: Springer; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shimer MT, Täuber UC, Pleimling M. Nonequilibrium relaxation and scaling properties of the two-dimensional coulomb glass in the aging regime. Europhys Lett. 2000;91:67005. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Daquila GL, Täuber UC. Slow relaxation and aging kinetics for the driven lattice gas. Phys Rev E Stat Nonlin Soft Matter Phys. 2011;83:051107. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.83.051107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bertin E, Bouchaud JP. Dynamical ultrametricity in the critical trap model . J Phys A Math Gen. 2002;35:3039. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vaknin A, Ovadyahu Z, Pollak M. Aging effects in an anderson insulator. Phys Rev Lett. 2000;84:3402–3405. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.84.3402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Orlyanchik V, Ovadyahu Z. Stress aging in the electron glass. Phys Rev Lett. 2004;92:066801. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.92.066801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ovadyahu Z, Pollak M. History-dependent relaxation and the energy scale of correlation in the Electron-Glass. Phys Rev B Condens Matter. 2003;68:184204. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ovadyahu Z. Quench-cooling procedure compared with the gate protocol for aging experiments in electron glasses. Phys Rev B Condens Matter. 2006;73:214204. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Amir A, Oreg Y, Imry Y. Mean-field model for electron-glass dynamics. Phys Rev B Condens Matter. 2008;77:165207. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grenet T. Symmetrical field effect and slow electron relaxation in granular aluminium. Eur Phys J B. 2003;32:275–278. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grenet T. Slow conductance relaxation in granular aluminium films. Phys Status Solidi C. 2004;1:9–12. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grenet T, Delahaye J, Sabra M, Gay F. Anomalous field effect and glassy behaviour in granular aluminium thin films: Electron glass? Eur Phys J B. 2007;56:183–197. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Amir A, Oreg Y, Imry Y. Slow relaxations and aging in the electron glass. Phys Rev Lett. 2009;103:126403. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.103.126403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Amir A, Oreg Y, Imry Y. Electron glass dynamics. Annu Rev Condens Matter Phys. 2011;2:235–262. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ludwig S, Nalbach P, Rosenberg D, Osheroff D. Dynamics of the destruction and rebuilding of a dipole gap in glasses. Phys Rev Lett. 2003;90:105501. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.90.105501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ludwig S, Osheroff D. Field-induced structural aging in glasses at ultralow temperatures. Phys Rev Lett. 2003;91:105501. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.91.105501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nalbach P, Osheroff D, Ludwig S. Non-equilibrium dynamics of interacting tunneling states in glasses. J Low Temp Phys. 2004;137:395–452. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Borini S, Boarino L, Amato G. Slow conductivity relaxation and simple aging in nanostructured mesoporous silicon at room temperature. Phys Rev B Condens Matter. 2007;75:165205. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Amir A, Borini S, Oreg Y, Imry Y. Huge (but finite) time scales in slow relaxations: Beyond simple aging. Phys Rev Lett. 2011;107:186407. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.107.186407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Benford F. The law of anomalous numbers. Proc Am Philos Soc. 1938;78:551–572. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Orlyanchik V, Ovadyahu Z. Electron glass in samples approaching the mesoscopic regime. Phys Rev B Condens Matter. 2007;75:174205. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bernamont J. Fluctuations de potential aux bornes dun conducteur metallique de faible volume parcouru par un courant. Ann Phys Leipzig. 1937;7:71. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ziel AVD. On the noise spectra of semi-conductor noise and of flicker effect. Physica. 1950;16:359–372. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dutta P, Horn PM. Low-frequency fluctuations in solids: 1/f noise. Rev Mod Phys. 1981;53:497–516. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Weissman MB. 1/f noise and other slow, nonexponential kinetics in condensed matter. Rev Mod Phys. 1988;60:537–571. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Amir A, Oreg Y, Imry Y. Localization, anomalous diffusion, and slow relaxations: A random distance matrix approach. Phys Rev Lett. 2010;105:070601. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.105.070601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Harrison WA. Elementary Electronic Structure. Singapore: World Scientific; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shockley W. On the statistics of individual variations productivity in research laboratories. Proc IRE. 1957;45:279–290. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Montroll EW, Shlesinger MF. On 1/f noise and other distributions with long tails. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1982;79:3380–3383. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.10.3380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Imry Y. Introduction to Mesoscopic Physics. New York: Oxford Univ Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Blair DL, Kudrolli A. Geometry of crumpled paper. Phys Rev Lett. 2005;94:166107. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.94.166107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bouchaud JP, Vincent E, Hammann J. Towards an experimental determination of the number of metastable states in spin-glasses? J Phys I France. 1994;4:139–146. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ivanov PC, et al. From 1/f noise to multifractal cascades in heartbeat dynamics. Chaos. 2001;11:641–652. doi: 10.1063/1.1395631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Amir A, Oreg Y, Imry Y. 1/f noise and slow relaxations in glasses. Ann Phys. 2009;18:836–843. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Onsager L. Reciprocal relations in irreversible processes. i. Phys Rev. 1931;37:405–426. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gutenberg B, Richter C. Seismicity of the Earth and Associated Phenomena. Princeton: Princeton Univ Press; 1954. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Utsu T. Representation and analysis of the earthquake size distribution: A historical review and some new approaches. Pure Appl Geophys. 1999;155:509–535. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Newcomb S. Note on the frequency of use of the different digits in natural numbers. Am J Math. 1881;4:39–40. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nigrini M. The use of Benford’s law as an aid in analytical procedures. Auditing. 1997;16:52–67. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bouchbinder E, Langer JS. Linear response theory for hard and soft glassy materials. Phys Rev Lett. 2011;106:148301. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.106.148301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bouchbinder E, Langer JS. Shear-transformation-zone theory of linear glassy dynamics. Phys Rev E Stat Nonlin Soft Matter Phys. 2011;83:061503. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.83.061503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kohlrausch R. Theorie des elektrischen Rückstandes in der Leidner Flasche. Ann Phys. 1854;91:179. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Phillips JC. Stretched exponential relaxation in molecular and electronic glasses. Rep Prog Phys. 1996;59:1133. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nesbitt JR, Hebard AF. Time-dependent glassy behavior of interface states in Al - Alox - Al tunnel junctions. Phys Rev B Condens Matter. 2007;75:195441. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Palmer RG, Stein DL, Abrahams E, Anderson PW. Models of hierarchically constrained dynamics for glassy relaxation. Phys Rev Lett. 1984;53:958–961. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Huber DL. Statistical model for stretched exponential relaxation in macroscopic systems. Phys Rev B Condens Matter. 1985;31:6070–6071. doi: 10.1103/physrevb.31.6070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Colaiori F, Moore MA. Stretched exponential relaxation in the mode-coupling theory for the Kardar-Parisi-Zhang equation. Phys Rev E Stat Nonlin Soft Matter Phys. 2001;63:057103. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.63.057103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sturman B, Podivilov E, Gorkunov M. Origin of stretched exponential relaxation for hopping-transport models. Phys Rev Lett. 2003;91:176602. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.91.176602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]