Abstract

Purpose

The objective of this qualitative study was to develop the items and support the content validity of the PedsQL™ Sickle Cell Disease Module for pediatric patients with sickle cell disease (SCD).

Methods

The iterative process included multiphase qualitative methodology. A literature review on SCD was conducted to generate domains of interest for the individual in-depth interviews. Ten healthcare experts with clinical experience in SCD participated in the development of the conceptual framework. A total of 13 pediatric patients with SCD ages 5–18 and 18 parents of patients ages 2–18 participated in the individual in-depth interviews. A total of 33 pediatric patients with SCD ages 5–18 and 39 parents of patients ages 2–18 participated in individually conducted cognitive interviews that included both think aloud and cognitive debriefing techniques to assess the interpretability and readability of the item stems.

Results

Six domains were derived from the qualitative methods involving patient/parent interviews and expert opinion, with content saturation achieved, resulting in 48 items. The six domains consisted of items measuring Pain Intensity/Location (9 items), Pain Interference (11 items), Worry (7 items), Emotions (3 items), Disease Symptoms/Treatment, (12 items), and Communication (6 items).

Conclusions

Qualitative methods involving pediatric patients and parents in the item development process support the content validity for the PedsQL™ SCD Module. The PedsQL™ SCD Module is now undergoing national multisite field testing for the psychometric validation phase of instrument development.

Keywords: Sickle cell disease, PedsQL™, Health-related quality of life, Patient-reported outcomes, Pediatrics, Qualitative methods

Introduction

Sickle cell disease is a hereditary chronic disease characterized by complications such as recurrent painful vasoocclusive crises or stroke that result in frequent hospitalizations. The evaluation of the disease burden and treatment effect on those with sickle cell disease has traditionally focused on measuring the number of hospitalizations, occurrence of painful crises, determining laboratory values or calculating mortality data [1–3].

The last decade has witnessed a significant increase in the development and utilization of pediatric health-related quality of life (HRQOL) measures in an effort to improve patient health and well-being and to determine the value of healthcare services. Although several generic HRQOL instruments, including the PedsQL™ 4.0 Generic Core Scales and Children’s Health Questionnaire, have been validated in the pediatric sickle cell disease (SCD) population [4–7], a disease-specific HRQOL instrument is essential to understanding the particular health issues most important for pediatric patients with SCD from the patient’s perspective. In addition, a sickle cell disease-specific HRQOL instrument would be expected to be more sensitive to detecting change in health status over time within a population of children with SCD [8, 9]. However, historically, there have been no HRQOL instruments available to more specifically measure the HRQOL of children with SCD. In order to better understand differences in health status within the population of children with SCD and to enhance the ability to measure the impact of disease modifying therapies, we developed the items for a new disease-specific HRQOL instrument targeted to pediatric SCD utilizing qualitative methods.

Qualitative methods, such as individual in-depth interviews and cognitive interviewing techniques, have emerged as the standard methodology for developing items and supporting content validity for new HRQOL instruments [10, 11] and have served as the foundation for previous PedsQL™ Disease-Specific Modules [12–19]. These qualitative methods are consistent with recent Food and Drug Administration (FDA) guidelines on patient-reported outcomes (PROs) measures [20], and as such can help support the content validity of newly developed disease-specific HRQOL items [21]. The final FDA Guidance to Industry suggests the following iterative steps to develop a PRO: a comprehensive review of the literature, expert opinion, and the patient data collected with focus groups and/or individual interviews and cognitive interviews in order to develop a conceptual framework for relevant disease-specific domains, item generation guided by the conceptual framework, and the iterative process of revising the items and item content based on patient cognitive interviews [22].

The present study reports the methods and results of the qualitative research utilized to develop the new PedsQL™ Sickle Cell Disease Module for pediatric patients with SCD and support its content validity.

Methods

Development of the items for the PedsQL™ Sickle Cell Disease Module followed the PedsQL™ methodology and theoretical framework for module development consistent with the final FDA Guidance to Industry [20].

The study team consisted of a clinician with over 15 years of research and clinical experience in treating patients and families with SCD (J.A.P.), the developer (J.W.V.) of the PedsQL™, and two research coordinators, one of whom had previous qualitative research experience and led all of the interviews.

Individual in-depth interviews and individually conducted cognitive interviews were audiotaped and transcribed by a project assistant. Both the coordinators and the administrative assistant were trained in the interview methodology, and followed the PedsQL™ Module Development written instructions.

Study population

Pediatric patients with SCD ages 5–18 years of age and parents of children with SCD ages 2–18 years were recruited from the clinic of the Midwest Sickle Cell Disease Center in Milwaukee, Wisconsin (see Figs. 1, 2, 3). Patients were recruited using purposive sampling in order to ensure that all age groups and the full spectrum of clinical phenotypes of the disease were represented.

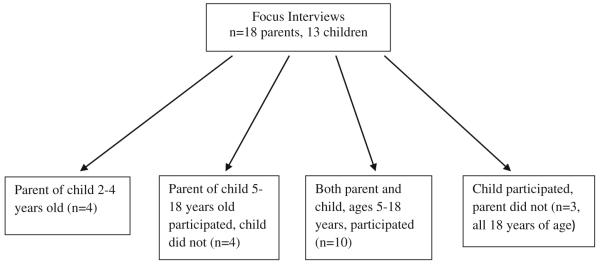

Fig. 1.

Focus interview population

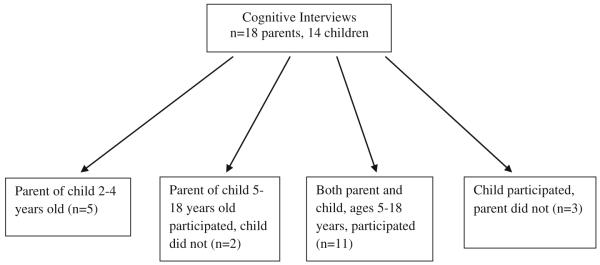

Fig. 2.

Cognitive interview population

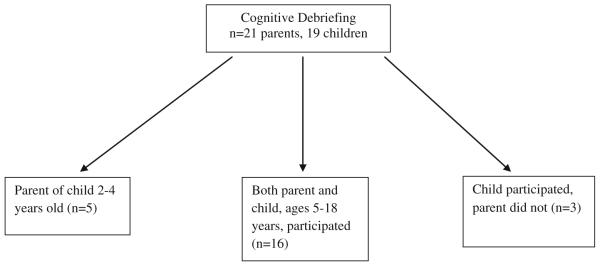

Fig. 3.

Cognitive debriefing population

Item generation

Literature review

A comprehensive literature review examining research in SCD for the years 2003–2008 was conducted using three databases (Medline, CINAHL, and PsychInfo) to generate information on issues of importance for the individual in-depth interviews. The keywords searched were anemia, SCD, and hemoglobinopathy, and these terms were merged with the following key words: symptoms, side effects, therapeutics, adherence, and anxiety.

Healthcare expert opinion

An expert panel of healthcare providers/workers who care for patients with SCD was assembled to review and comment on the relevance of the domains and associated areas of interest generated from the literature review. Six physicians, two nurses, and two social workers, all of whom care for children with SCD clinically, completed the survey (Appendix A). An electronic survey using Constant Contact was conducted by our team to determine the expert panel’s opinion on the relevance of topics (using a Likert scale) relating to SCD. The panel was recruited by email to complete the survey and represented six sickle cell disease centers from the United States.

Individual in-depth interviews

The individual in-depth interviews were audiotaped and later transcribed by an administrative assistant. For each interview, a second person (either another research coordinator or an administrative assistant) was present to take detailed notes. The interviews were conducted in a private room either in the clinic or in the Translational Research Unit of the hospital. Individual in-depth interviews rather than focus groups were conducted given the difficulty in arranging for patients and parents from different families to meet together at the same time.

A total of 13 pediatric patients with SCD ages 5–18 years and 18 parents of pediatric patients with SCD ages 2–18 years participated in the individual in-depth interviews (Fig. 1). Parents and children ages 8–18 were interviewed separately. Children of ages 5–7 years were interviewed with their parent present. The individual in-depth interviews were conducted using a semi-structured interview format to elicit themes around issues identified as being important from our literature review and expert panel. Additionally, we began and ended the questioning with very general, open ended questions (What is the biggest concern about your child’s health? Is there anything else about your child’s health that is important to their quality of life?) and included more specific questions in between that focused on themes from the literature review and expert panel (See script Table 1).

Table 1.

Semi-structured interview script

| Introduction/ground rules |

|---|

| Introductory question—what is the first thing that comes to mind when you hear the phrase “sickle cell disease”? |

| Transition question—what is the biggest concern about your health? |

| Physical |

| In what ways, if any, does having sickle cell disease keep you from doing physical activities you want to do? |

| In what ways, if any, does having sickle cell disease get in the way of taking care of yourself? |

| What sickle cell disease symptoms bother you most? |

| In what ways, if any, does being afraid of having pain or other sickle cell symptoms affect what you do? |

| Psychological/social |

| What things, if any, do you worry about because you have sickle cell disease? |

| Do you worry about death from sickle cell disease? |

| Does your sickle cell disease affect how you get along with other people? How so? |

| In what ways does your sickle cell disease cause problems, if any, in your family? |

| In what ways, if any, does having sickle cell disease make you feel good or bad about who you are? |

| Happy? |

| Unhappy? |

| Afraid? |

| School |

| What problems, if any, do you have at school because you have sickle cell disease? |

| What do you like best about school? |

| What do you like least about school? |

| In what ways, if any, does sickle cell disease affect how you get along with other kids at your school? |

| Other |

| Is there anything else about your health or your sickle cell disease that is important to your quality of life? |

| Ending question |

A content analysis to determine themes was performed independently by 3 members of the research team when the individual in-depth interviews were completed [23]. Attention was paid to the frequency, extensiveness, specificity, and emotion of the comments/themes. In addition, the interviews were analyzed for saturation of themes and stopped when saturation was reached. Saturation was met when no new themes are generated with additional interviews. Major themes were identified from the data as part of the content analysis by the team members. The themes identified were grouped into appropriate disease and treatment related areas after discussing and reaching consensus on any differences in the common and relevant themes identified.

Cognitive think aloud interviews

Individually conducted cognitive techniques were utilized to elicit feedback from children and parents on the themes identified and their appropriateness for SCD. They were asked to utilize a 5-point rating scale (1 = not at all important to 5 = very important) to determine the importance of each domain on the child’s HRQOL. This cohort did not include anyone that was a part of the individual in-depth interviews. A total of 18 parents and 14 children (Fig. 2) participated in this phase.

Development of items

Themes that were identified were then operationalized into items. These items were designed to measure the domains/symptoms/problems identified as important for SCD by the patients, families, and healthcare experts. The reading level of the items was designed to be targeted to a second-grade reading level and grammar and syntax structurally equivalent to those in the existing PedsQL™ item bank. Readability was assessed using the Flesch–Kincaid readability test. The PedsQL™ item bank was searched for relevant items that matched a domain or topic area already identified and incorporated into the questionnaire to maintain consistency in wording with the validated modules within the PedsQL™ item bank. The recall period and the Likert-type response scale match that of the generic and disease-specific PedsQL™ instruments [24]. The PedsQL™ 5-point Likert-type response scale utilized across child self-report, adolescent self-report, and parent proxy-report (0 = never a problem; 1 = almost never a problem; 2 = sometimes a problem; 3 = often a problem; 4 = almost always a problem) was adopted and has also previously undergone extensive cognitive interviews for a number of Pediatric PROMIS scales and found to be acceptable and understood by both children and parents [25–28].

Cognitive debriefing and pre-testing of the module

The PedsQL™ Sickle Cell Disease Module items were administered to a separate sample of 19 patients and 21 parents (Fig. 3) who had not previously participated in the individual in-depth interviews or cognitive interviewing phases. Cognitive debriefing techniques (asking each respondent what each item means, item by item) were employed to determine whether patients and parents understood each item and to determine whether there were any items that were difficult or confusing to answer or that were upsetting. Wording changes were made at this point if indicated to further improve the understandability of individual items based on patient and parent feedback. Item content saturation was achieved when no new information was elicited from the patients and parents.

Participants were given $25 gift cards for participating.

Results

Item generation

From the literature review, five broad domains were generated as were multiple themes/subdomains within each of these overarching domains: symptoms, treatment (side effects and adherence to treatment), appearance, worry, and social (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Domains generated by literature review

| Symptoms | Treatment/side effects/treatment adherence |

Appearance | Worry | Social |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pain | Compliance with medications | Pale | Worry about having to get treatment |

Feel inferior/differed from others |

| Headache | Side effects of common medications: |

Yellow eyes | ||

| Fatigue/tired | Small size pre-pubertal appearance |

Worry about side effects from medicine |

||

| Difficulty breathing | Nausea | |||

| Bed wetting | Constipation | Worry about dying | ||

| Weakness | Fatigue/sedation | |||

| Difficulty walking | Bad taste | |||

| Swelling of hands and feet |

Hair loss Weight gain |

|||

| Fever | Itching | |||

| Difficulty in school performance |

“Side effect” of treatment Pain (from IV insertion/IM injections/lab draws) Death |

The healthcare providers’ expert panel emphasized the themes of pain, fatigue, issues surrounding treatment such as side effects and compliance problems, physical functioning problems such as walking and ability to get around, and problems with self-esteem such as feeling isolated.

Individual in-depth interviews

Individual in-depth interviews included children from each age group and gender (Table 3) and resulted in the identification of numerous crosscutting themes across child and parent input, healthcare expert opinion, and the SCD literature (Table 4). The children and parents identified the recurrent and unpredictable nature of SCD, especially painful episodes, as particularly salient. Worry was a prominent theme, and children and parents expressed how they worried about many facets of their illness including worrying about experiencing complications of the disease and its treatment, about having to be hospitalized or seen in the emergency department, and about communication issues such as others not understanding their illness. Some examples of specific quotes from our individual in-depth interviews follow and demonstrate these themes: “….the process of it getting worse or when it’s starting because it throbs before it starts and then it stops and then it go again”; “You feel excruciating pain, like, wherever your sickle cell gets stopped up. So you know that it’s a crisis and you know that it’s here”; “…if I have pain I can stay at home but if it’s like very bad I go to the hospital”; “….it’s just always a process of waiting because it’s going to happen whether you like it or not”; “Just the pain comes randomly”; “I’m worried that the sickle cell will affect my whole dream and I won’t be able to participate in anything”. Fatigue from the disease and treatment was also a common concern (Table 5). Fatigue was expressed in the interviews as “not having enough energy”, “feeling tired”, and “tire quickly”. “Like when I get low of energy I really cannot do everything that I’m used to doing”.

Table 3.

Demographics of parents and children with sickle cell disease represented in focus interviews, cognitive interviews, and cognitive debriefing

| Focus interviews N = 21 (%) |

Cognitive interviews N = 21 (%) |

Cognitive debriefing N = 24 (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Child characteristics | |||

| Gender | |||

| Female | 10 (47.6) | 7 (33.3) | 16 (66.7) |

| Age | |||

| 2–4 years | 4 (19.0) | 5 (23.8) | 5 (20.8) |

| 5–7 years | 4 (19.0) | 5 (23.8) | 5 (20.8) |

| 8–12 years | 6 (28.6) | 5 (23.8) | 6 (25.0) |

| 13–18 years | 7 (33.3) | 6 (28.6) | 8 (33.3) |

| Genotype | |||

| Hemoglobin SS | 17 (81.0) | 15 (71.4) | 16 (66.7) |

| Hemoglobin Sβ0thalassemia | 0 | 1 (4.8) | 0 |

| Hemoglobin SC | 2 (11.8) | 2 (9.5) | 7 (29.2) |

| Hemoglobin Sβ+thalassemia | 1 (4.76) | 2 (9.5) | 1 (4.2) |

| Other | 1 (4.76) | 1 (4.8) | 0 |

| Disease severity | |||

| Severe | 15 (71.4) | 14 (66.7) | 12 (50.0) |

| One or more of the following: | |||

| Frequent hospitalizations for painful episodes (≥3 in prior 3 years) |

7 (33.3) | 5 (23.8) | 6 (27.3) |

| Acute chest syndrome | 10 (47.6) | 6 (28.6) | 6 (27.3) |

| Stroke | 5 (23.8) | 3 (14.3) | 1 (4.5) |

| Silent stroke | 3 (14.3) | 2 (11.8) | 1 (4.5) |

| Mild disease | |||

| None of the above | 6 (28.6) | 7 (33.3) | 12 (50.0) |

| Other sickle cell disease complications | |||

| Splenic sequestration | 3 (14.3) | 3 (14.3) | 8 (33.3) |

| Bacteremia | 2 (9.5) | 1 (4.8) | 3 (12.5) |

| Aplastic crisis | 3 (14.3) | 4 (19.0) | 1 (4.2) |

| Osteomyelitis | 2 (9.5) | 1 (4.8) | 2 (8.3) |

| Priapism | 2 (14.3) | 1 (4.2) | |

| Avascular necrosis | 2 (14.3) | ||

| Meningitis | 1 (4.8) | 1 (4.2) | |

| Parent characteristics | |||

| Total parents | 18 (85.7) | 18 (85.7) | 21 (87.5) |

| Parent gender | |||

| Female | 18 (85.7) | 14 (77.8) | 18 (75.0) |

| Parent age, average years (standard deviation) | 34.5 (6.7) | 36.5 (8.6) | 33.4 (5.9) |

Table 4.

Crosscutting themes

| Domain | Themes |

|---|---|

| Pain | Severity and frequency of pain episodes |

| Level of concern about unpredictability of pain episodes | |

| Limiting activity to prevent painful episodes | |

| Extent to which painful episodes limit daily activities | |

| Fear of having pain episodes | |

| Control of pain | |

| Fatigue | Extent to which fatigue interferes with school/work |

| Extent to which fatigue limits daily activities | |

| Extent to which the disease interrupts sleep | |

| Emotion | Extent to which disease affects mood causing anger, anxiety and fear |

| Disease symptoms & treatment | Extent to which disease and treatment limit activities |

| Extent to which treatment affects my health | |

| Social/communication | Extent to which disease and treatment affect peer relationships |

| Extent to which disease and treatment affect relationships with healthcare providers |

Table 5.

Pediatric sickle cell disease individual in-depth interviews

| Domain | Pediatric patient with sickle cell disease |

|---|---|

| Pain | 5–7-year-olds, 8–12-year-olds and 13–18-year-olds |

| Most reported they experience pain symptoms recurrently | |

| Most reported unpredictability and recurrent nature of painful episodes made planning activities difficult | |

| Some report they often have excruciating pain | |

| Some reported limiting their activities to try and prevent painful episodes from occurring | |

| 8–12-year-olds and 13–18-year-olds | |

| Most report they worry they will have a painful episode | |

| Fatigue | 5–7-year-olds, 8–12-year-olds and 13–18-year-olds |

| Most report feeling fatigued and having low energy | |

| Many report feeling winded or short of breath | |

| 8–12-year-olds and 13–18-year-olds | |

| Most report being tired at school or work | |

| Some report fatigue limits what they are able to do | |

| Most report pain interrupts their sleep or makes it difficult to sleep | |

| Emotion | 5–7-year-olds, 8–12-year-olds and 13–18-year-olds |

| Many report they worry they will have to go to the hospital | |

| 8–12-year-olds and 13–18-year-olds | |

| Some report being angry when others do not understand their disease | |

| Some report they have fear that others do not understand their sickle cell disease | |

| Some report being angry they have sickle cell disease | |

| Some report they worry about getting complications of sickle cell disease | |

| Some report they worry about their disease getting worse | |

| Disease symptoms and treatment |

5–7-year-olds, 8–12-year-olds and 13–18-year-olds |

| Most report they limit themselves from doing activities to try and prevent painful episodes from occurring | |

| Most report they cannot do what others can due to their disease | |

| Some report they find it difficult to remember to take their medications | |

| 8–12-year-olds and 13–18-year-olds | |

| Some report their medications make them feel fatigued | |

| Some report their medications do not work to make them feel better | |

| Some report they do not like having to take medications | |

| Some report they have yellow eyes from their disease | |

| 13–18-year-olds | |

| Some report they have difficulty caring for themselves when they are sick | |

| Social/communication | 5–7-year-olds, 8–12-year-olds and 13–18-year-olds |

| Most report the unpredictability of the disease prevents them from doing things they want and need to do | |

| 8–12-year-olds and 13–18-year-olds | |

| Most report they wanted to be treated the same as others | |

| Most report they want to be alone when sick | |

| Some report they do not fit in with their peers and they get bullied by others | |

| Some report they get used to experiencing illness and pain from their disease and learn to cope in their own way | |

| Some report healthcare providers do not always listen to them | |

| Some report they wish their family, friends and healthcare providers understood their disease better | |

| Some report that others think they are faking their symptoms sometimes |

A total of 50 themes were identified from the content analysis of the individual in-depth interviews and then grouped into 6 content areas/domains: Pain (9 themes), Pain Impact (11 themes), Worry (9 themes), Emotion (3 themes), My Disease: Symptoms and Treatment (12 themes), and Communication (6 themes). In addition, a fatigue theme was elicited frequently and extensively in the interviews, and the decision was made to include the 18-item PedsQL™ Multidimensional Fatigue Scale to capture this theme since this three dimensional scale has been widely validated in other pediatric chronic conditions [14, 29–31], including pediatric chronic pain patients [32–34] and pediatric patients with sickle cell disease [4].

Cognitive think aloud interviewing

The participants were given the rating scale and the questionnaire items to assess the importance of the identified themes. Revisions were made based on this feedback, for example, children and parents often thought of going to the hospital as being synonymous with also having to go to the emergency department or clinic. However, patients distinguished that they worried about having to stay in the hospital as being different from visiting the clinic or needing to go to the emergency department. Thus, the item was revised, to clarify the construct, into “worry I might have to stay overnight in the hospital”. In addition, two themes/items were deleted, “it is hard for me to walk one block when I have pain” as being able to walk one block is asked on the generic PedsQL™ 4.0 Generic Core Scales and “I worry I will have a child with SCD” due to concern about appropriateness of asking this question and because of the inherent developmental nature of the item.

Operationalization of items

A preliminary PedsQL™ Sickle Cell Disease Module was constructed and consisted of 49 items and 6 scales (Pain, Pain Impact, Worry, Emotion, My Disease: Symptoms and Treatment, Communication), consistent with the format and time frame, instructions, and response choices utilized by the Peds-QL™ 4.0 Generic Core Scales and Disease-Specific Modules [24].

Cognitive debriefing

Individually conducted cognitive debriefing of the Peds-QL™ Sickle Cell Disease Module items was conducted with 21 parents and 19 children with SCD (Fig. 3) who had not previously participated in the individual in-depth interviews or cognitive think aloud interviewing as noted earlier. Based on patient and parent feedback, some items were shortened to improve readability. The item “It is hard for you to do everything others can do because you might get pain if you do too much” was noted to be at the 7th grade reading level so the item was shortened to “It is hard for you to do what others do because you might get pain” which is at the 3rd grade reading level. Two items were added: (1) “It is hard to tell others you have SCD” was added because this was mentioned multiple times as important to patients when we conducted cognitive debriefing, and (2) “It is hard for me to control my pain” was added as some patients did not understand the word “manage” in the item “It is hard for me to manage my pain” and it was felt that the construct measured by the two items was somewhat different. Finally, three items were removed from the younger 2–7-year-old child report forms due to developmental inappropriateness (remembering to take medicine and worrying about having a stroke and acute chest syndrome). After pre-testing, the instrument consisted of the same 6 scales and a total of 45–48 items depending on the age form.

Final empirically derived items and scales (Appendix B)

Six scales were derived from the qualitative methods, with item content saturation achieved at 48 items after cognitive debriefing (see Appendix B for the patient self-report items). The six scales consist of Pain Intensity/Location (9 items, e.g., “I hurt a lot”; “I hurt in my chest”) Pain Interference (11 items, e.g. “I have trouble moving when I have pain”; “I miss school when I have pain”), Worry (7 items, e.g., “I worry I might have a chest crisis”; “I worry that others will not know what to do if I have pain”), Emotions (3 items, e.g., “I feel mad when I have pain”), Disease Symptoms/Treatment (12 items, e.g., “I get yellow eyes when I am sick”; “I do not like how I feel after I take my medicine”), and Communication (6 items, e.g., “It is hard for me to tell others I have SCD”).

Discussion

This study presents the iterative phases of item development and content validation for a disease-specific HRQOL instrument for pediatric patients with SCD, the PedsQL™ Sickle Cell Disease Module. Children and families eagerly participated in discussions that provided the essential content needed to generate the sickle cell disease-specific themes. We achieved data saturation during the individual in-depth interviews with 13 pediatric patients with SCD and 18 parents. Prior qualitative research has demonstrated that data saturation can occur within the first twelve interviews, with basic elements for meta-themes present as early as the first six interviews [35].

It has become essential to describe in exacting detail the process for item development including supporting the content validity of a patient-reported outcome measure by following a rigorous set of standardized qualitative methods in order to meet the current requirements set by the research community and regulatory bodies such as the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the valid assessment such measures [10, 20]. Following the existing PedsQL™ Module Development Methodology and current standards for instrument development, the conceptual framework, content validity, and 48 items were developed comprising six scales.

Not unexpectedly, the domains derived from the qualitative methods centered on pain and its interference with daily living along with disease-related symptoms and treatment and the impact of disease and treatment on the patient’s well-being. Themes such as the child not being able to plan to participate in events because he/she might get sick or have pain or worrying about future pain episodes emphasized the perspective of the patients and parents from their daily experiences with SCD, themes that traditional clinical indicators do not typically account for in routine clinical practice and clinical research. These themes underscore the importance of qualitative research in developing patient-reported outcome measures.

Our study may be limited due to the single-site population of patients and parents involved. In addition, it is possible that our themes and domains do not include all that are pertinent to sickle cell disease given the complexity of this disease and the vast age range we studied. In addition, we attempted to use focus group methodology, but after three failed attempts at hosting focus groups where only one parent–child pair attended, we began using individual in-depth interviews to obtain the relevant data.

We are currently conducting the next iterative phase of instrument development, that is, field testing of the newly developed items and scales, to determine the feasibility, reliability, validity, and factor structure of the PedsQL™ Sickle Cell Disease Module and the PedsQL™ Multidimensional Fatigue Scale in pediatric patients with SCD. This quantitative phase will help us determine whether any items are redundant and can be dropped and further the understanding of the factor structure of the instrument.

In conclusion, we developed the items and established the content validity of the PedsQL™ Sickle Cell Disease Module for patient self-report for ages 5–18 years and parent proxy-report of children with SCD ages 2–18 years. It is anticipated that the new PedsQL™ Sickle Cell Disease Module will be used in conjunction with the PedsQL™ 4.0 Generic Core Scales and the PedsQL™ Multidimensional Fatigue Scale. We expect this newly developed instrument will aid us in understanding in even greater detail the health and well-being of children with SCD and will be a valuable instrument to monitor the health status over time in SCD patients, as well as assess the benefits of treatment or interventions for this pediatric population.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (U54 HL090503, Project 3 and CTSI 1-UL1-RR031973).

Abbreviations

- SCD

Sickle cell disease

- HRQOL

Health-related quality of life

- PedsQL™

Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory™

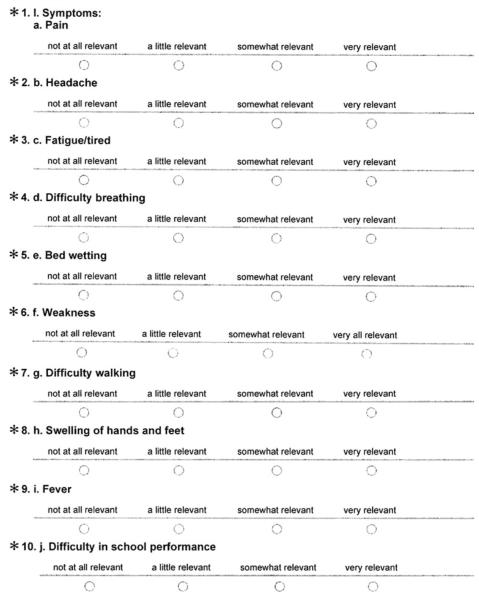

Appendix A. The Development of the PedsQL Sickle Cell Disease Module-Expert Panel Review

* Required Questions(s) Progress:

Relevance of issues

We are asking for your help in devising a questionnaire that will be used to assess the health-related quality of life of children with sickle cell disease. Below is a list of disease and treatment-related symptoms relevant to children with sickle cell disease.

For each issue, Please indicate the the extent to which you find it relevant for children With sickle cell disease. Specifically, consider how common it may be for children with sickle cell disease and how much trouble it can cause when it happens to determine relevane.

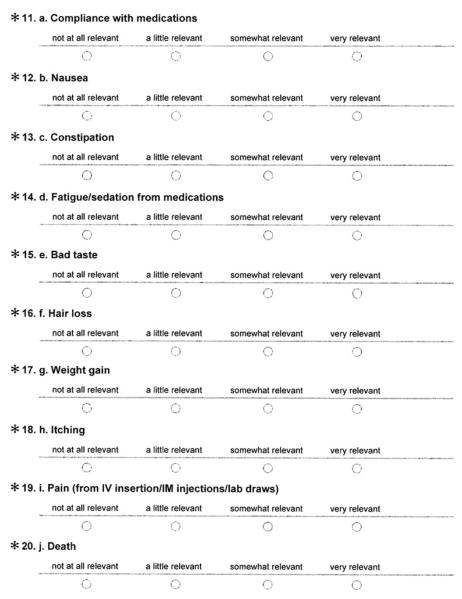

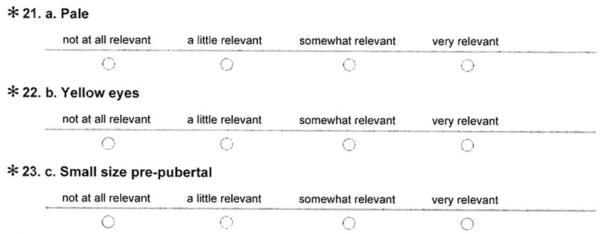

II. Treatment Side Effects/Treatment Adherence

III. Appearance

IV. Worry

V. Social

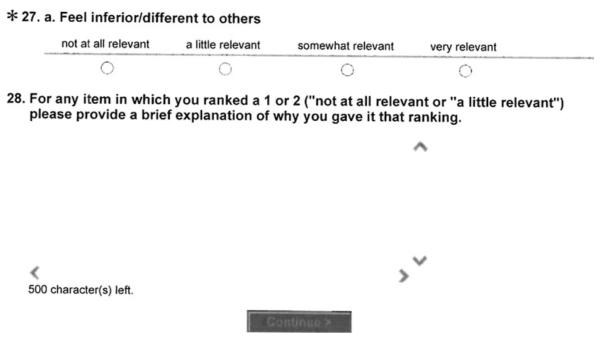

Breadth of coverage

Progress:

Please list anything else which you may feel is of relevance and which was not listed here. Please explain briefly why you feel this is important to include.

Importance of issues

Progress:

In order to determine the importance of issues, please mark 5 to 10 items in the complete list (I. Symptoms, II. Treatment Side Effects/Treatment Adherence, III. Appearace, IV. Worry, Social that, in your opinion, should definitely be included in the final questionaire.

37. I. Symptoms

□ a. Pain

□ b. Headache

□ c. Fatigue/tired

□ d. Difficulty breathing

□ e. Bed wetting

□ f. Weakness

□ g. Difficulty walking

□ h. Swelling of hands and feet

□ i. Fever

□ j. Difficulty in school performance

38. II. Treatment Side Effects/ Treatment Adherence

□ a. Compliance with medications

□ b. Nausea

□ c. Constipation

□ d. Fatigue/sedation

□ e. Bad taste

□ f. Hair loss

□ g. Weight gain

□ h. Itching

□ i. Pain (from IV insertion/IM injections/lab draws)

□ j. Death

39. III Appearance

□ a. Pale

□ b. Yellow eyes

□ c. Small sizw pre-pubertal

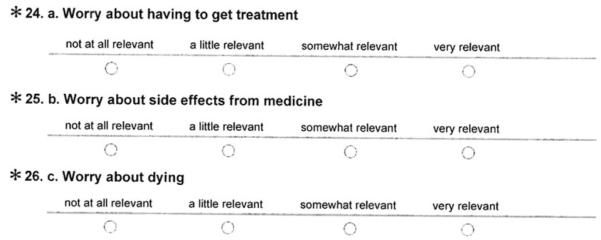

40. IV. Worry V. Social

□ a. Worry about having to get treatment

□ b. Worry about side effects from medicine

□ c. Worry about dying

□ IV. a. Feel inferior/different to others

Non important issues

In order to determine the importance of issues, please mark 5 to 10 items in the complete list (I. Symptoms, II. Treatment Side Effects/ Treatment Adherence, III. Appearance, IV. Worry, Social) that, in your opinion, should definitely NOT be included in the final questionnaire.

41. I. Symptoms

□ a. Pain

□ b. Headache

□ c. Fatigue/tired

□ d. Difficulty breathing

□ e. Bed wetting

□ f. Weakness

□ g. Difficulty walking

□ h. Swelling of hands and feet

□ i. Fever

□ j. Difficulty in school performance

42. II. Treatment Side Effects/ Treatmetn Aherence

□ a. Compliance with medications

□ b. Nausea

□ c. Constipation

□ d. Fatigue/sedation

□ e. Bad taste

□ f. Hair loss

□ g. Weight gain

□ h. Itching

□ i. Pain (from IV insertion/IM injections/lab draws)

□ j. Death

43. III. Apperance

□ a. Pale

□ b. Yellow eyes

□ c. Small size pre-pubertal

44. IV. Worry and V. Social

□ a. Worry about having to get treatment

□ b. Worry about side effects from medicine

□ c. Worry about dying

□ v. Social Feel inferior to/different than others

Appendix B. PedsQL™ sickle cell disease module scales child self-report item content1

About my pain and hurt

I hurt a lot

I hurt all over my body

I hurt in my arms

I hurt in my legs

I hurt in my stomach

I hurt in my chest

I hurt in my back

I have pain every day

I have pain so much that I need medicine

About my pain impact

It is hard for me to do things because I might get pain

I miss school when I have pain

It is hard for me to run when I have pain

I want to be alone when I have pain

It is hard to have fun when I have pain

I have trouble moving when I have pain

It is hard to stay standing when I have pa

It is hard for me to take care of myself when I have pain

It is hard for me to do what others can do because I might get pain

I wake up at night when I have pain

I get tired when I have pain

About me worrying

I worry that I will have pain

I worry that others will not know what to do if I have pain

I worry when I am away from home

I worry I might have to go to the emergency room

I worry I might have to stay overnight in the hospital

I worry I might have a stroke

I worry I might have a chest crisis

About my emotions

Needle sticks scare me

I feel mad I have sickle cell disease

I feel mad when I have pain

About my disease symptoms and treatment

I have headaches

I get yellow eyes when I am sick

It is hard for me to manage my pain

It is hard for me to control my pain

It is hard for me to remember to take my medicine

I do not like how I feel after I take my medicine

I do not like the way my medicine tastes

My medicine make me sleepy

I worry about whether my medicine is working

I worry about whether my treatments are working

My medicine does not make me feel better

Other kids make me feel different because of how I look

About communication

It is hard for me to tell others when I am in pain

It is hard for me to tell the doctors and nurses how I feel

It is hard for me to ask the doctors and nurses questions

It is hard for me when others do not understand about my sickle cell disease

It is hard for me when others do not understand how much pain I feel

It is hard for me to tell others I have sickle cell disease

Footnotes

Conflict of Interests Dr. Varni holds the copyright and the trademark for the PedsQL™ and receives financial compensation from the Mapi Research Trust, which is a nonprofit research institute that charges distribution fees to for-profit companies that use the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory™.

The number of items might change as a function of the quantitative analyses.

Contributor Information

Julie A. Panepinto, Department of Pediatrics, Children’s Hospital of Wisconsin of the Children’s Research Institute/Medical College of Wisconsin, Hematology/Oncology/Bone Marrow Transplantation, 8701 Watertown Plank Road, Milwaukee, WI 53226, USA

Sylvia Torres, Department of Pediatrics, Children’s Hospital of Wisconsin of the Children’s Research Institute/Medical College of Wisconsin, Hematology/Oncology/Bone Marrow Transplantation, 8701 Watertown Plank Road, Milwaukee, WI 53226, USA.

James W. Varni, Department of Pediatrics, College of Medicine, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX, USA; Department of Landscape Architecture and Urban Planning, College of Architecture, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX, USA

References

- 1.Charache S, Terrin ML, Moore RD, Dover GJ, Barton FB, Eckert SV, et al. Effect of hydroxyurea on the frequency of painful crises in sickle cell anemia. Investigators of the multicenter study of hydroxyurea in sickle cell anemia. New England Journal of Medicine. 1995;332:1317–1322. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199505183322001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Platt OS, Brambilla DJ, Rosse WF, Milner PF, Castro O, Steinberg MH, et al. Mortality in sickle cell disease. Life expectancy and risk factors for early death. New England Journal of Medicine. 1994;330:1639–1644. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199406093302303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Platt OS, Thorington BD, Brambilla DJ, Milner PF, Rosse WF, Vichinsky E, et al. Pain in sickle cell disease. Rates and risk factors. New England Journal of Medicine. 1991;325:11–16. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199107043250103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dampier C, Lieff S, LeBeau P, Rhee S, McMurray M, Rogers Z, et al. Health-related quality of life in children with sickle cell disease: A report from the comprehensive sickle cell centers clinical trial consortium. Pediatric Blood & Cancer. 2010;55:485–494. doi: 10.1002/pbc.22497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Panepinto JA, O’Mahar KM, DeBaun MR, Rennie KM, Scott JP. Validity of the Child Health Questionnaire for use in children with sickle cell disease. Journal of Pediatric Hematology/oncology. 2004;26:574–578. doi: 10.1097/01.mph.0000136453.93704.2e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Panepinto JA, Pajewski NM, Foerster LM, Hoffmann RG. The performance of the PedsQL™ Generic Core Scales in children with sickle cell disease. Journal of Pediatric Hematology/oncology. 2008;30:666–673. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0b013e31817e4a44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Panepinto JA, O’Mahar KM, DeBaun MR, Loberiza FR, Scott JP. Health-related quality of life in children with sickle cell disease: Child and parent perception. British Journal Haematology. 2005;130:437–444. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2005.05622.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Varni JW, Limbers CA. The Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory: Measuring pediatric health-related quality of life from the perspective of children and their parents. Pediatric Clinics of North America. 2009;56:843–863. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2009.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patrick DL, Deyo RA. Generic and disease-specific measures in assessing health status and quality of life. Medical Care. 1989;27:S217–S233. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198903001-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lasch KE, Marquis P, Vigneux M, Abetz L, Arnould B, Bayliss M, et al. Pro development: Rigorous qualitative research as the crucial foundation. Quality of Life Research. 2010;19:1087–1096. doi: 10.1007/s11136-010-9677-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Irwin DE, Varni JW, Yeatts K, DeWalt DA. Cognitive interviewing methodology in the development of a pediatric item bank: A patient reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS) study. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2009;7(3):1–10. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-7-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Varni JW, Burwinkle TM, Berrin SJ, Sherman SA, Artavia K, Malcarne VL, et al. The PedsQL™ in pediatric cerebral palsy: Reliability, validity, and sensitivity of the generic core scales and cerebral palsy module. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology. 2006;48:442–449. doi: 10.1017/S001216220600096X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Varni JW, Burwinkle TM, Jacobs JR, Gottschalk M, Kaufman F, Jones KL. The PedsQL™ in type 1 and type 2 diabetes: Reliability and validity of the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory™ Generic Core Scales and type 1 diabetes module. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:631–637. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.3.631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Varni JW, Burwinkle TM, Katz ER, Meeske K, Dickinson P. The PedsQL™ in pediatric cancer: Reliability and validity of the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory™ Generic Core Scales, Multidimensional Fatigue Scale, and Cancer Module. Cancer. 2002;94:2090–2106. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Varni JW, Burwinkle TM, Rapoff MA, Kamps JL, Olson N. The PedsQL™ in pediatric asthma: Reliability and validity of the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory™ Generic Core Scales and Asthma Module. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2004;27:297–318. doi: 10.1023/b:jobm.0000028500.53608.2c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Varni JW, Seid M, Knight TS, Burwinkle TM, Brown J, Szer IS. The PedsQL™ in pediatric rheumatology: Reliability, validity, and responsiveness of the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory™ Generic Core Scales and Rheumatology Module. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2002;46:714–725. doi: 10.1002/art.10095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goldstein SL, Graham N, Warady BA, Seikaly M, McDonald R, Burwinkle TM, et al. Measuring health-related quality of life in children with ESRD: Performance of the Generic and ESRD-Specific Instrument of the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory™ (PedsQL™) American Journal of Kidney Diseases. 2008;51:285–297. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2007.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Palmer SN, Meeske KA, Katz ER, Burwinkle TM, Varni JW. The PedsQL™ Brain Tumor Module: Initial reliability and validity. Pediatric Blood & Cancer. 2007;49:287–293. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weissberg-Benchell J, Zielinski TE, Rodgers S, Greenley RN, Askenazi D, Goldstein SL, et al. Pediatric health-related quality of life: Feasibility, reliability and validity of the PedsQL™ Transplant Module. American Journal of Transplantation. 2010;10:1677–1685. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2010.03149.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.DA F. Guidance for industry: Patient-reported outcome measures: Use in medical product development to support labeling claims. Food and Drug Administration, US Department of Health and Human Services; Rockville, MD: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lasch KE, Marquis P, Vigneux M, Abetz L, Arnould B, Bayliss M, et al. Pro development: Rigorous qualitative research as the crucial foundation. Quality of Life Research. 2010;19:1087–1096. doi: 10.1007/s11136-010-9677-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brod M, Tesler LE, Christensen TL. Qualitative research and content validity: Developing best practices based on science and experience. Quality of Life Research. 2009;18:1263–1278. doi: 10.1007/s11136-009-9540-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krueger RA, Casey MA. Focus groups: A prac- tical guide for applied research. 3rd ed Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Varni J. The PedsQL™ 4.0 Measurement Model for the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory™. Administration guidelines. (version 4.0) 2004 http://wwwpedsqlorg/pedsqladminhtml.

- 25.Irwin DE, Stucky BD, Thissen D, DeWitt EM, Lai JS, Yeatts K, et al. Sampling plan and patient characteristics of the promis pediatrics large-scale survey. Quality of Life Research. 2010;19:585–594. doi: 10.1007/s11136-010-9618-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Varni JW, Stucky BD, Thissen D, DeWitt EM, Irwin DE, Lai JS, et al. PROMIS pediatric pain interference scale: An item response theory analysis of the pediatric pain item bank. Journal of Pain. 2010;11:1109–1119. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2010.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Irwin DE, Stucky BD, Langer MM, Thissen D, DeWitt EM, Lai JS, et al. An item response analysis of the pediatric PROMIS anxiety and depressive symptoms scales. Quality of Life Research. 2010;19:595–607. doi: 10.1007/s11136-010-9619-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yeatts K, Stucky BD, Thissen D, Irwin DE, Varni JW, DeWitt EM, et al. Construction of the pediatric asthma impact scale (PAIS) for the patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS) Journal of Asthma. 2010;47:295–302. doi: 10.3109/02770900903426997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marcus SB, Strople JA, Neighbors K, Weissberg-Benchell J, Nelson SP, Limbers CA, et al. Fatigue and health-related quality of life in pediatric inflammatory bowel disease. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2009;7:554–561. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Varni JW, Limbers CA, Bryant WP, Wilson DP. The PedsQL™ Multidimensional Fatigue Scale in type 1 diabetes: Feasibility, reliability, and validity. Pediatric Diabetes. 2009;10:321–328. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5448.2008.00482.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Varni JW, Limbers CA, Bryant WP, Wilson DP. The PedsQL™ Multidimensional Fatigue Scale in pediatric obesity: Feasibility, reliability, and validity. International Journal of Pediatric Obesity. 2010;5:34–42. doi: 10.3109/17477160903111706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gold JI, Mahrer NE, Yee J, Palermo TM. Pain, fatigue, and health-related quality of life in children and adolescents with chronic pain. Clinical Journal of Pain. 2009;25:407–412. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e318192bfb1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Varni JW, Burwinkle TM, Limbers CA, Szer IS. The PedsQL™ as a patient-reported outcome in children and adolescents with fibromyalgia: An analysis of OMERACT domains. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2007;5(9):1–12. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-5-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Varni JW, Burwinkle TM, Szer IS. The PedsQL™ Multidimensional Fatigue Scale in pediatric rheumatology: Reliability and validity. Journal of Rheumatology. 2004;31:2494–2500. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guest G, Bunce A, Johnson L. How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods. 2006;18:59–82. [Google Scholar]