Abstract

A dementia diagnosis is challenging to deliver and to hear, yet agreement about a diagnosis is essential for effective dementia care. We examined consensus about the results of a dementia evaluation in 90 patients assessed at an Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center. Diagnostic impressions were obtained from five sources: 1) the physician’s chart diagnosis, 2) the patient who was evaluated, 3) a companion present at the evaluation, 4) a diagnostic summary written by a nurse present during the evaluation, and 5) raters who watched a video of the diagnostic disclosure conversation. Overall, diagnostic consensus was only moderate. Patients and companions exhibited just fair agreement with one another. Agreement was better between physicians and companions compared to physicians and patients, though imperfect between the physician and video raters and the written summary. Agreement among sources varied by dementia severity, with lowest agreement occurring in instances of very mild dementia. This study documents discrepancies that can arise in diagnostic communication, which could influence adjustment to a dementia diagnosis and decisions regarding future planning and care.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, dementia, diagnostic disclosure, doctor-patient communication, patient education

INTRODUCTION

Practice guidelines are nearly universal in recommending that physicians disclose the diagnosis when they suspect dementia in their patients1-4. These guidelines are consistent with findings that patients and caregivers prefer to know about a dementia diagnosis5, 6 and with ethical principles about patients’ autonomy and right to know their medical diagnosis7, 8. Moreover, early detection and diagnosis have a number of advantages, such as enabling patients to start pharmacologic treatment to receive its full therapeutic benefit, as well as allowing patients and family members to collaborate in advanced care planning well before cognitive impairments advance9.

Despite consensus about the importance of disclosing a dementia diagnosis, there is some ambiguity about the extent to which patients and their companions actually understand what they have been told during diagnostic consultations. At present, only a few research studies have evaluated patient or companion awareness of dementia after a diagnosis has been given. In one study, patients with known dementia diagnoses were asked whether they have problems with memory and whether a physician had ever told them that they have a memory problem or dementia. Approximately 64% of participants reported memory problems, but only 26% reported having been previously told that they have memory problems or dementia by a physician10. There was also a sizeable discrepancy between patients and companions in their understanding of whether a dementia diagnosis had been given, with only 37% agreement between patient and companions. In a similar study, only 47% of dementia patients were able to identify their diagnosis correctly, and only 33% reported that anyone had ever spoken with them about their diagnosis11. A third study asked patients and caregivers to write down immediately after a dementia evaluation the diagnosis they remember being told, and only 40% of patients and 82% of caregivers could correctly name the diagnosis that was provided. Despite this imperfect agreement, most of the caregivers who were asked about their experiences believed they received an appropriate amount of information from the physician12.

Reasons for the discrepancy between what patients and companions are actually told and what they report being told are not well understood. Inaccuracies may be due to difficulty comprehending the diagnosis during the diagnostic conversation, difficulty recalling information after the diagnostic conversation, or some combination of the two. Patients even in the early stages of dementia may experience anosognosia and may be unaware of their cognitive deficits13,14. Understandable lapses in memory among patients with dementia, however, do not account for the discrepancy in reports among cognitively intact caregivers. Instead, one possibility is that the devastating nature of the news may overwhelm family members, leading to denial of the diagnosis15. Family members may have genuine reasons why they do not want a loved one to have dementia (e.g., concern about their loved one, dread about what responsibilities they may face in the future as caregivers), and those reasons may be powerful motivators to disregard diagnostic information, or at least “hear” the news in a way that meets their psychological needs16.

Another key actor in diagnostic conversations is the clinician delivering the diagnosis, who may add to confusion about the diagnosis. With the intent of being kind and caring, physicians may use language that is less than direct (e.g., “You may have early symptoms that could be Alzheimer’s disease”)17. They may use technical terminology (e.g., “dementia,” “cognitive impairment”) that is not easily understandable by lay people. And they may control the diagnostic conversation, in ways both subtle and explicit, and offer little opportunity for follow-up questions or clarification18. In some cases, given the complexities of diagnosis early in the disease, physicians may be themselves unsure of the diagnosis and communicate that uncertainty to patients and family. In all these situations, vague or incomplete information about a diagnosis can leave patients and caregivers uncertain about what they have been told or can give them an opening to misinterpret the physician’s intended message.

The current study was designed to provide a systematic evaluation of agreement among physicians, patients, companions, and other professionals about the results of a dementia diagnostic workup. In the context of an initial dementia evaluation, we examined diagnostic impressions from multiple sources. We also evaluated the extent to which agreement across these sources varied depending on the patient’s disease severity.

METHODS

Participants

The study was approved by the Washington University Human Research Protection Office. Recruitment was conducted through the Memory and Aging Project (MAP) of the Washington University Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (ADRC). Individuals who were interested in enrolling in longitudinal studies of healthy aging and dementia of the Alzheimer type (DAT) were told about the current study and contacted by telephone if they expressed openness to participation. Potential participants were invited to be part of a project that explored “how individuals respond to receiving news about their memory functioning.” After a description of the study, people who expressed interest were mailed consent forms and a baseline questionnaire before their first visit to the MAP. Participants and companions brought the completed baseline questionnaire and consent form to their initial MAP appointment. In no cases were there concerns about patients’ ability to give informed consent, consistent with a previous ADRC study demonstrating that individuals with very mild and mild dementia understood consent information for the MAP19. Physicians signed a consent form prior to their evaluation with their first patient.

Ninety patient and companion dyads were enrolled as a unit; characteristics of the patients and companions appear in Table 1. The physicians who conducted the evaluations and delivered the diagnosis (n = 10) had been working an average of 8.2 years in dementia care, with most specializing in neurology or geriatrics.

Table 1.

Characteristics of physicians, patients, and companions.

| Physicians (n = 10) |

Patients (n = 90) |

Companions (n = 90) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| M/n | SD/% | M/n | SD/% | M/n | SD/% | |

| Age (yrs.) | – | – | 71.1 | 8.0 | 62.9 | 13.5 |

| Female | 4 | 40% | 54 | 60% | 64 | 71% |

| White | 8 | 80% | 79 | 88% | 79 | 88% |

| Education (yrs.) | – | – | 14.8 | 3.1 | 15.1 | 2.8 |

| ADRC Experience (yrs.) | 8.20 | 7.30 | – | – | – | – |

| Specialty | ||||||

| Neurology | 5 | 50% | – | – | – | – |

| Geriatrics | 4 | 40% | – | – | – | – |

| Geriatric Psychiatry | 1 | 10% | – | – | – | – |

| Diagnostic outcome | ||||||

| CDR 0 (no dementia) | – | – | 29 | 32% | – | – |

| CDR 0.5 (very mild dementia) | – | – | 40 | 45% | – | – |

| CDR 1 (mild dementia) | – | – | 21 | 23% | – | – |

| Dementia Type | ||||||

| Dementia of the Alzheimer Type | – | – | 50 | 56% | – | – |

| Frontotemporal Dementia | – | – | 2 | 2% | – | – |

| Diffuse Lewy Body Disease | – | – | 2 | 2% | – | – |

| Posterior Cortical Dysfunction | – | – | 1 | 1% | – | – |

| Medication-Induced Cognitive Dysfunction | – | – | 1 | 1% | – | – |

| Other/Unclear | – | – | 5 | 6% | – | – |

| Relationship to patient | ||||||

| Spouse/Partner | – | – | – | – | 55 | 61% |

| Child | – | – | – | – | 20 | 22% |

| Other family | – | – | – | – | 9 | 10% |

| Friend | – | – | – | – | 6 | 7% |

Note. Information on race was not reported by three companions.

Procedure

Patients were seen for evaluation of possible changes in cognition. Patients attended an initial visit that included a comprehensive review of medical history, as well as a physical and neurological examination. Cognitively intact companions were interviewed separately by the physician to ascertain their perception of the patient’s cognitive and behavioral changes. Immediately following the evaluation, patients and companions sitting together received diagnostic feedback in a conversation that was videotaped. During the session, the physician shared his or her impression of the patient’s diagnosis. Also present was a nurse, who wrote down the diagnostic formulation and other comments made by the physician; this sheet was given to patients and companions at the conclusion of the conversation. In cases in which the participant received a dementia diagnosis, the feedback session also typically included information about symptoms and their progression, treatment options, care planning, and community service referrals. At the conclusion of the clinical assessment, the physician determined the probable diagnosis and assigned a clinical dementia rating (CDR)20, 21 to represent degree of impairment: no dementia (CDR = 0), very mild dementia (CDR = 0.5) or mild dementia (CDR = 1). Note that the CDR was not revealed to the patient or companion.

For diagnostic quality assurance, a second clinician reviewed DVD recordings of 50% of all assessments within 2-4 weeks. In cases where there was diagnostic disagreement, the case was resolved in a consensus conference. For the sample in this study, there were 5 disagreements in CDR score (6% of the sample) between the original and second clinician. None involved resolution from CDR 0 (cognitively normal) to CDR 0.5 (very mild dementia) or from CDR 0.5 to CDR 0; all were CDR 0.5 to 1 or 1 to 0.5. There were 9 disagreements (10%) in precise type of dementia, 8 of which were resolved in favor of the original clinician (i.e., did not change from what was communicated to the patient). In the one case in which the formal diagnosis did change, it did not change the clinical impression that the patient was cognitively impaired. Consequently, in the current study there were no cases in which further contact was made with the patient or companion to clarify the results of the consensus process.

Diagnostic Impressions

Diagnostic impressions were collected from five sources: 1) the physician, 2) the patient’s recollection of what they were told, 3) the patient’s companion’s recollection of what they had been told, 4) a written summary from a nurse present for the visit, and 5) trained raters who viewed a video of the diagnostic disclosure conversation. The physician’s diagnostic impression was taken from the assigned CDR value, where a value of 0 was interpreted as “no dementia” and values of 0.5 or 1 were interpreted as “dementia.” Immediately after the disclosure session, physicians were also asked to rate their perceptions of how well the patient and the companion understood the diagnostic feedback, ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much).

Patients and companions were contacted separately by telephone 2-3 days after the evaluation and asked the following question: “[Do you/Does your family member] have Alzheimer’s disease or dementia?” Patient/companion response options included “Yes,” “No,” or “I don’t know.” Of note, these questions did not differentiate between whether patients and companions understood the diagnosis and whether they agreed with the diagnosis. Patients and companions were also asked to rate the following statements, adapted from the Dementia Care Satisfaction Questionnaire22, on a 5 point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree): 1) The results of the evaluation were thoroughly explained; 2) I received results that were clear; and 3) I feel like I understand the information that was provided to me.

Two raters (BDC and EKP) independently reviewed the nurse feedback form and judged whether the form indicated the presence of a dementia diagnosis (Yes, No, or Clinician Uncertain). These same two raters reviewed the videotape of each disclosure session and judged whether a dementia diagnosis was communicated by the physician (Yes, No, or Clinician Uncertain). Ratings of the feedback forms and videotapes were completed blind to the patient’s actual diagnosis. Interrater reliability based on Cohen’s kappa (K)19 was very good (K = 0.98 for the feedback forms; K = 0.83 for the videotapes).

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to evaluate the sociodemographic characteristics of the sample. Percent agreement on the diagnostic impression was calculated between each diagnostic source (physician, patient, companion, feedback form, and video rating) for the total sample. The physician was assigned a dummy “I Don’t Know/Uncertain” category with 0 values to facilitate comparisons with the other diagnostic sources. The sample was then split by dementia severity (no dementia, very mild dementia, mild dementia) and percent agreement was again calculated among the fives sources. Agreement between diagnostic sources was assessed using Cohen’s kappa (K)23. A kappa of 1.0 indicates perfect agreement and 0.0 agreement no better than chance. We used the following guidelines for interpreting kappa: poor = < 0.20, fair = 0.21 – 0.40, moderate = 0.41 – 0.60, good = 0.61 – 0.80, very good = 0.81 – 1.0024. Pearson’s chi square tests were used to assess whether agreement between patients or companions with other sources differed by patient/companion sex or whether the companion was a spouse/nonspouse. We created dichotomous variables to indicate whether patients/companions agreed with the other sources. Independent samples t tests were used to assess whether patient or companion education differed depending on dichotomous agreement between patients/companions and other sources. Additional independent samples t tests were used to assess whether physician impressions of patient/companion understanding, as well as patient/companion ratings of thoroughness, clarity, and perceived understanding of the diagnosis, differed when patient/companion reports either agreed or disagreed with the physician’s. Eight patients and 7 companions were missing responses, and 5 videos were unavailable for coding due to error in the recording process. All statistical analyses were implemented with PASW 18.025.

RESULTS

Overall agreement

Consensus about the patient’s diagnosis was moderate but far from perfect: mean agreement = 76.6%, SD = 11.7%); mean K = 0.59 (see Table 2). In general, patients demonstrated only fair agreement with other sources, including their companion (agreement = 65.9%, K = 0.40) and physician (agreement = 61.0%, K = 0.32). Companions demonstrated better agreement than the patients with all sources, including good agreement with the physician (agreement = 81.9%, K = 0.65). Agreement between the physician and nurse feedback forms (agreement = 86.7%, K = 0.74) and the physician and video ratings (agreement = 84.7%, K = 0.72) also was good but not perfect.

Table 2.

Percent agreement and interrater agreement for diagnostic impressions among all sources and by dementia severity.

| All Sources | Patient n = 82 % (K) |

Companion n = 83 % (K) |

Nurse Form n = 90 % (K) |

Video n = 85 % (K) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physician CDR | 61.0% (0.32) | 81.9% (0.65) | 86.7% (0.74) | 84.7% (0.72) |

| Patient | - | 65.9% (0.40) | 62.2% (0.37) | 64.9% (0.41) |

| Companion | - | - | 81.9% (0.68) | 84.6% (0.73) |

| Nurse Form | - | - | - | 91.8% (0.86) |

| By Dementia Severity | Patient % |

Companion % |

Nurse Form % |

Video % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Dementia (n = 29) | ||||

| Physician CDR | 88.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 96.6% |

| Patient | - | 88.0% | 88.0% | 88.0% |

| Companion | - | - | 100.0% | 96.2% |

| Nurse Form | - | - | - | 96.6% |

| Very Mild Dementia (n = 40) | ||||

| Physician CDR | 47.2% | 66.7% | 77.5% | 72.2% |

| Patient | - | 55.5% | 55.5% | 59.4% |

| Companion | - | - | 69.4% | 71.9% |

| Nurse Form | - | - | - | 91.7% |

| Mild Dementia (n = 21) | ||||

| Physician CDR | 52.4% | 85.7% | 85.7% | 90.0% |

| Patient | - | 57.1% | 42.9% | 45.0% |

| Companion | - | - | 81.0% | 90.0% |

| Nurse Form | - | - | - | 85.0% |

Note: All Cohen’s Kappa (K) values significant at p < 0.001.

Overall agreement did not vary by patient/companion sex or by whether the companion was a spouse or nonspouse (p > 0.05 for all analyses). Patient education was unrelated to agreement between patient and companion, physician, or video rating (ps > 0.05). Patients in agreement with the nurse feedback form had significantly more years of education (mean = 15.3, SD = 3.0) than those who disagreed (mean = 13.6, SD = 2.7; t(75) = -2.37, p < 0.05). Companion agreement with other sources was not meaningfully related to companion education (ps > 0.05). Perceptions of Understanding

Patients and companions provided very positive ratings of thoroughness of feedback (patients: mean = 4.51, SD = 0.68; companions: mean = 4.62, SD = 0.59), clarity of results (patients: mean = 4.33, SD = 0.77; companions: mean = 4.55, SD = 0.76), and perceived understanding of the diagnostic results (patients: mean = 4.32, SD = 0.77; companions: mean = 4.61; SD = 0.51), suggesting at least self-perceived comprehension was high. Patient and companion ratings of thoroughness, clarity, and perceived understanding did not differ when physicians-patients or physicians-companions agreed or disagreed, (ps > 0.05).

Physician impressions of patient understanding differed by physician-patient agreement (t(75) = -3.45, p < 0.01); patients in agreement with the physician were perceived as having better understanding of the feedback (mean = 4.47, SD = 0.78) than those who did not agree (mean = 3.70, SD = 1.18). Among the patients who were not in agreement with the physician’s diagnosis, 57% were rated by the physician as either 4 or 5, where 5 indicated that the physician perceived them to very much understand the feedback. Physician ratings of companion understanding did not differ by physician-companion agreement (p > 0.05); companions who both agreed (mean = 4.63, SD = 0.60) and did not agree (mean = 4.92, SD = 0.28) with the physician’s diagnosis were perceived by physicians to have a high understanding of the diagnostic feedback.

Agreement by dementia severity

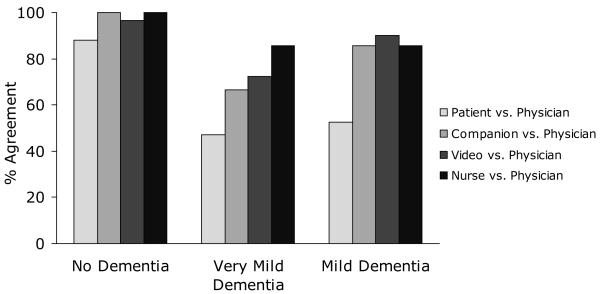

Diagnostic consensus varied by dementia severity (Table 2). Concordance values for dementia severity are reported only as percent agreement, as Cohen’s kappa could not be calculated because at least one variable in the majority of the two-way tables used to calculate measures of association was a constant, reflecting no variability in that variable. Overall consensus among the five sources was lowest for patients with very mild dementia (mean agreement = 66.7%, SD = 12.9%) as compared to patients with mild dementia (mean agreement = 71.5%, SD = 19.6%) and patients with no dementia (mean agreement = 94.1%, SD = 5.5%).

Patient agreement with the physician was consistently lower than agreement among other sources, regardless of dementia severity, and the greatest disagreement was seen in patients with very mild (mean agreement = 47.2%) and mild (mean agreement = 52.4%) dementia (Figure 1). In contrast, mean agreement between the four nonpatient sources was better but still imperfect regarding diagnoses of no dementia (mean agreement = 98.2%, SD = 1.9), very mild dementia, (mean agreement = 74.9%, SD = 9.0) and mild dementia (mean agreement = 86.2%, SD = 3.4). Among the 32 patients who disagreed with the physician’s diagnosis, 25 (78%) believed that they did not have dementia when the physician’s diagnosis indicated they did. Among the 28 patients who disagreed with their companion, 16 (57%) believed they did not have dementia when their companion believed they did. For the 15 companions who disagreed with the physician’s diagnosis, 10 (67%) believed that the patient did not have dementia when the physician’s diagnosis indicated they did.

Figure 1.

Sources’ agreement with physician, by dementia severity.

DISCUSSION

The present study demonstrates that consensus about a dementia diagnosis among patients, companions, and physicians is moderate but imperfect. Agreement was lowest between patients and the other four sources, as patients tended to report no dementia when others believed the patient had dementia. Additionally, nearly 20% of companions were not in agreement with the physician. Concordance rates between the physician, nurse summary forms, and disclosure video ratings demonstrated that professional sources also were not in complete agreement. Patient/companion sex, relationship between patient and companion, and patient/companion education had limited or no effect on agreement. Despite imperfect agreement, patients and companions frequently reported receiving thorough feedback that included clear diagnostic results, and they thought their understanding of the results was good, an impression reiterated by physicians, even in instances when patients and companions did not agree with the physician’s diagnosis. At least four factors may account for discrepancies in diagnostic agreement.

Cognitive Impairment

Cognitive deficits could prevent patients from understanding the diagnostic conversation, encoding diagnostic information, or retrieving the information they are told. Indeed, unawareness of deficits is common in dementias13, 14, and most cases of disagreement were ones in which patients claimed not to have dementia even when others said they did. However, cognitive impairment would not be a likely explanation for disagreement exhibited by companions.

Emotional Interference

Previous qualitative studies have documented reports of distress related to hearing a dementia diagnosis15, 26, and that distress could overwhelm individuals and reduce attention and comprehension during diagnostic feedback. However, prior results with this sample suggest that patients and companions, on average, do not experience significant distress. In fact, many reported less depression and anxiety after diagnosis, expressing relief at having an explanation for symptoms and a plan for the future27. This was true among patients and companions who acknowledged receiving a dementia diagnosis, suggesting that lack of distress cannot be attributed to unawareness of the diagnosis.

Physician Language

Another possible explanation for disagreement lies in the language used to convey the diagnosis. Even when a physician feels relatively certain about the presence of dementia, the clinician may use language that qualifies the diagnosis (e.g., “this could be,” “what we might be seeing is”) as a way of mitigating negative emotional reactions. However, qualified language offers patients and companions leeway to misinterpret or to translate what is said into a diagnostic outcome consistent with their hopes and needs. For example, companions who rely upon the patient to fulfill certain roles in their relationship (e.g., managing finances or homemaking) may be unwilling to view that patient as incapacitated16. Physicians also may use ambiguous language when they themselves are uncertain of the diagnosis, as suggested by our findings of imperfect agreement between professional sources.

Dementia Severity

Diagnostic agreement is further complicated by dementia severity, with poorest consensus occurring when patients had the earliest signs of dementia. In these instances, patients and companions tend to report no dementia, whereas professional sources report uncertainty about the diagnosis. This finding may reflect the complexity of diagnosing very mild dementia, when the earliest of symptoms of dementia may be difficult to disentangle from normal age-related cognitive decline28. Although diagnostic uncertainty might be understandable, it is important to recognize that even when physicians convey their uncertainty, some patients and family members hear certainty. Moreover, other professionals may compound the uncertainty. In our sample, written feedback forms shared with patients and companions were not always consistent with the diagnostic information shared by the physician. Given all the potential for misunderstanding, information about a dementia diagnosis needs to be presented in as clear a manner is possible, even when the diagnosis itself is unclear.

Limitations

The present study includes methodological limitations worth noting. The research was conducted at an Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center and may not reflect the practice variability seen in strictly clinical settings. Given that we found discordance even in this highly structured and specialized research setting, however, disagreements may be even more common in standard community practice. Furthermore, agreement with the physician was based on CDR values, which were finalized in consensus conferences after the disclosure sessions were completed. However, diagnoses rarely changed during these conferences and cannot explain all cases of disagreement. Although it is possible that physicians relied on more vague language when uncertain about the precise CDR, this would not account for the discrepancies in agreement detected across all gradations of dementia severity.

In addition, the question used to assess patient and companion diagnostic impressions did not differentiate between understanding the diagnosis and agreeing with it. This is an important distinction, as it affects the clinical implications posed by disagreement. Poor diagnostic understanding of the diagnosis might warrant additional steps to ensure comprehension, such as asking patients and companions to explain their understanding of the diagnosis. In contrast, a difference of opinion might be best addressed by offering a more transparent explanation of how the physician came to the diagnosis, including specific information regarding current symptoms.

Conclusions and Implications

To our knowledge, this is the first prospective study to evaluate agreement between patients, families, and multiple professional sources about the results of a dementia evaluation. The results of this study confirm that physicians cannot assume patients or caregivers understand a dementia diagnosis, even if physicians believe diagnostic information was clear. Questions remain about why diagnostic concordance is imperfect across sources, and more research is needed to evaluate how well physicians believe patients and companions understand the diagnosis and whether this affects their choice of language, time spent explaining the diagnosis, and other behaviors. Additionally, disagreement between patients, companion, and physicians should be carefully characterized to ascertain whether lack of agreement is due to poor understanding or a difference in opinion. Ambiguities in diagnostic communication and comprehension might impede optimal adjustment to a dementia diagnosis and future care planning.

The diagnostic disclosure process detailed in this study is only the first step in a continuum of care. Disclosure must not be an isolated event, but an ongoing process that checks for patient and companion comprehension. Further, even when patients and companions are able to comprehend the initial diagnosis, it remains unclear how well they are able to integrate additional information about future care planning and support services. These details may be better addressed after patients and companions have the opportunity to review diagnostic information, consider its implications, and generate additional questions3. Follow-up visits may ensure that patients and companions receive appropriate access to therapies and support services as they continue to adjust to the diagnosis.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Patrick Brown, Ph.D., Mary Coats, R.N., Elizabeth Grant, Ph.D., and Monica Mills, M.A., for their important contributions to this work.

Support for this project was provided by a grant from the University of Missouri Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders Program (CX, BDC). Support for the Washington University Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center comes from grants from the National Institute on Aging, P50-AG05681 and P01-AG03991 (JCM, CX).

Footnotes

Portions of this work were presented previously at the Annual Meeting of the Gerontological Society of America, Atlanta, GA, November 22, 2008.

Disclosure: All authors report no conflicts of interest.

This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Richards S, Hendrie H. Diagnosis, management, and treatment of Alzheimer disease: a guide for the internist. Arch Intern Med. 1999 Apr 26;159(8):375–385. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.8.789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Post SG, Whitehouse PG. Fairhill guidelines on ethics of the care of people with Alzheimer’s disease: A clinical summary. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1995 Dec;43(12):1423–1429. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1995.tb06625.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alzheimer’s Association [Accessed November 20, 2009];Diagnostic disclosure. 2007 Jan 6; http://www.alz.org/professionals_and_researchers_diagnostic_disclosure.asp.

- 4.American Psychiatric Association Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with Alzheimer’s Disease and other dementias: Second edition. Am J Psychiatry. 2007 Dec;164(Suppl. 12):5–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith AP, Beattie BL. Disclosing a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: patient and family experiences. Can J Neurol Sci. 2001 Feb;28(Suppl. 1):S67–71. doi: 10.1017/s0317167100001220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Connell CM, Gallant MP. Spouse caregivers’ attitudes toward obtaining a diagnosis of a dementing illness. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1996 Aug;44(8):1003–1009. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1996.tb01881.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bell VM, Troxel D. An Alzheimer’s disease bill of rights. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 1994 Sep;9(5):3–6. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Drickamer MA, Lachs MS. Should patients with Alzheimer’s disease be told their diagnosis? N Engl J Med. 1992;326(14):947–951. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199204023261410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iliffe S, Walters K, Rait G. Shortcomings in the diagnosis and management of dementia in primary care: Towards an educational strategy. Aging Ment Health. 2000 Nov;4(4):286–291. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Campbell KH, Stocking CB, Hougham GW, et al. Dementia, diagnostic disclosure, and self-reported health status. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(2):296–300. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01551.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marzanski M, Chodosh J. On telling the truth to patients with dementia. West J Med. 2000 Nov;173(5):318–323. doi: 10.1136/ewjm.173.5.318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barrett AM, Orange W, Keller M, et al. Short-term effect of dementia disclosure: how patients and families describe the diagnosis. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006 Dec;54(12):1968–1970. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00992.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wagner MT, Spangenberg KB, Bachman DL, et al. Unawareness of cognitive deficit in Alzheimer disease and related dementias. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 1997;11(3):125–131. doi: 10.1097/00002093-199709000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Salmon E, Perani D, Collette F, et al. A comparison of unawareness in frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2008;79(2):176–179. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2007.122853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aminzadeh F, Byszewski A, Molnar FJ, et al. Emotional impact of dementia diagnosis: Exploring persons with dementia and caregivers’ perspectives. Aging Ment Health. 2007 May;11(3):281–290. doi: 10.1080/13607860600963695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pollitt PA, O’Connor DW, Anderson I. Mild dementia: Perceptions and problems. Ageing Soc. 1989;9(3):261–275. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carpenter BD, Dave J. Disclosing a dementia diagnosis: a review of opinion and practice, and a proposed research agenda. Gerontologist. 2004 Apr;44(2):149–158. doi: 10.1093/geront/44.2.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roter DL. The enduring and evolving nature of the patient-physician relationship. Patient Educ Couns. 2000 Jan;39(1):5–15. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(99)00086-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Buckles VD, Powlishta KK, Palmer JL, et al. Understanding of informed consent by demented individuals. Neurology. 2003;61(12):1662–1666. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000098933.34804.fc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morris JC. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): Current version and scoring rules. Neurology. 1993 Nov;43(11):2412–2414. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.11.2412-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hughes CP, Berg L, Danziger WL, et al. A new clinical scale for the staging of dementia. Br J Psychiatry. 1982 Jun;140:566–572. doi: 10.1192/bjp.140.6.566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van Hout HPJ, Vernooij-Dassen MJFJ, Hoefnagels WHL, et al. Measuring the opinions of memory clinic users: Patients, relatives and general practitioners. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2001 Sep;16(9):846–851. doi: 10.1002/gps.411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Langenbucher J, Labouvie E, Morgenstern J. Measuring diagnostic agreement. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1996;64(6):1285–1289. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.6.1285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Altman DG. Practical statistics for medical research. Chapman and Hall; London: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 25.PASW Statistics for Macintosh [computer program]. Version 18.0. SPSS Inc; Chicago: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Holroyd S, Turnbull Q, Wolf AM. What are patients and their families told about the diagnosis of dementia? Results of a family survey. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2002 Mar;17(3):218–221. doi: 10.1002/gps.552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carpenter BD, Xiong C, Porensky EK, et al. Reaction to a dementia diagnosis in individuals with Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008 Mar;56(3):405–412. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01600.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Galvin JE, Powlishta KK, Wilkins K, et al. Predictors of preclinical Alzheimer disease and dementia: A clinicopathologic study. Arch Neurol. 2005;62:758–765. doi: 10.1001/archneur.62.5.758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]