Abstract

Regulation of inducible nitric oxide synthase (NOS2) expression is important given the role of this enzyme in inflammation, control of infections and immune regulation. In contrast to tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) alone or CD40 stimulation alone, simultaneous stimulation of mouse macrophages through CD40 ligation and TNF-α led to up-regulation of NOS2 and nitric oxide production. This response was of functional relevance because CD40/TNF-α-stimulated macrophages acquired nitric oxide-dependent anti-Leishmania major activity. CD40 plus TNF-α up-regulated NOS2 independently of interferon-γ, interferon-α/β and interleukin-1. TNF receptor-associated factor 6 (TRAF6), an adapter protein downstream of CD40, appears to be required for NOS2 up-regulation because a CD40-TRAF6 blocking peptide inhibited up-regulation of NOS2 in CD40/TNF-α-stimulated macrophages. CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein-β (C/EBPβ), a transcription factor activated by TNF-α but not CD40, was required for NOS2 up-regulation because this enzyme was not up-regulated when C/EBPβ−/− macrophages received CD40 plus TNF-α stimulation. These results indicate that CD40 and TNF-α co-operate to up-regulate NOS2, probably via the effect of TRAF6 and C/EBPβ.

Keywords: CD40, macrophage, nitric oxide, parasite, signalling, tumour necrosis factor

Introduction

Inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS or NOS2) plays a central role in anti-microbial activity and has been implicated in immune regulation and defence against cancer as well as in the pathogenesis of various chronic inflammatory and autoimmune disorders.1–3 The expression of NOS2 and production of nitric oxide in macrophages is induced by cytokines and lipopolysaccharides (LPS).1,4 Although interferon-γ (IFN-γ) and LPS alone can induce NOS2 expression in mouse macrophages,1,5 cytokines and LPS usually act in synergistic pairs to induce NOS2 and nitric oxide in these cells.1,4–7 In this regard, tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), an important regulator of NOS2, requires IFN-γ to induce NOS2 and nitric oxide production in macrophages.5,8 Understanding the mechanisms of regulation of NOS2 expression is important given the ability of NOS2 to mediate both protective and detrimental effects to the host.

CD40 and lymphocyte function-associated antigen-1 are surface molecules engaged during T-cell–macrophage interaction that modulate macrophage activation and promote nitric oxide production.9,10 CD40 is a member of the TNF receptor (TNFR) superfamily that is expressed on macrophages and other haematopoietic as well as non-haematopoietic cells.11–13 CD40 is also capable of mediating protection against a variety of pathogens as well as promoting tissue damage in various chronic inflammatory disorders.11–14 Whereas CD40 regulates NOS2 expression, CD40 stimulation alone has been reported to be insufficient for NOS2 induction and nitric oxide production in macrophages and microglia.9,15–17 Co-stimulation with CD40 plus IFN-γ was required for NOS2 expression and nitric oxide production.15–17 Tumoristatic activity is one of the effector functions induced by CD40 in macrophages.18 Although a study reported that nitric oxide and TNF-α production partially mediates this effector function in CD40-activated macrophages, whether CD40 co-operates with TNF-α to induce NOS2 expression was not addressed.18

One of the key functions of NOS2 is to induce anti-microbial activity in macrophages. Leishmania major is a parasite that is susceptible to NOS2-dependent killing in macrophages.19,20 In addition, the CD40–CD154 (CD40 ligand) pathway is required for in vivo protection against L. major or Leishmania amazoniensis.21–23 However, CD40 stimulation of macrophages by itself has been reported not to be sufficient to induce anti-L. major activity.10,22 Here we tested whether CD40 and TNF-α co-operate to up-regulate NOS2 expression in macrophages and examined whether such an effect is of functional relevance by studying the induction of anti-L. major activity. In addition, we explored signalling molecules involved in the up-regulation of NOS2 in response to CD40/TNF-α stimulation.

Materials and methods

Animals

Specific pathogen-free female C57BL/6, BALB/c, B6/129, NOS2−/− (B6/129 background), IFN-γ−/− (BALB/c background) and interleukin-1 receptor-1−/− (IL-1R1−/−) mice (B6 background) were obtained from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). 129/SvEv mice were purchased from Taconic (Hudson, NY) and IFN-α/βR−/− mice (129/SvEv background) and CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein β−/− (C/EBPβ−/−) mice (B6 background) were gifts from Dr Clifford Harding (Case Western Reserve University) and Dr Maria Hatzoglou (Case Western Reserve University), respectively. Animals were 8–10 weeks old when used. Studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine.

Macrophages

Bone-marrow-derived macrophages were obtained by culturing bone marrow cells for 7 days in Teflon jars containing Iscove's modified Dulbecco's medium (IMDM) plus 30% L cell-conditioned medium, 10% fetal bovine serum (HyClone, Logan, UT) and 5% horse serum (HyClone).24 Resident peritoneal macrophages were collected by lavage with 2 ml ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline and cultured in complete medium comprising IMDM plus 10% fetal bovine serum.24 Macrophages were incubated as indicated with complete medium containing either a stimulatory anti-CD40 (1C10) or control (B39-4) monoclonal antibodies (mAbs, both at 10 μg/ml; BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA), recombinant mouse CD154 (3 μg/ml; Amgen, Thousand Oaks, CA), recombinant mouse TNF-α (250 pg/ml; PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ) or recombinant mouse IFN-γ (100 U/ml; PeproTech). Reagents were devoid of detectable endotoxin as assessed by Limulus assay (Sigma Chemical, St Louis, MO).

Immunoblot

Immunoblotting analysis was performed as previously described.24 Briefly, macrophages were lysed in buffer containing 20 mm Tris–HCl (pH 7·4), 100 mm NaCl, 10% glycerol, 1% Triton X-100, 100 mm NaF, 1 mm NaVO4, 1 mm benzamidine, 20 μg/ml leupeptin, 5 mm PMSF, and 20 μg/ml aprotinin (all from Sigma Chemical). Lysates were separated by SDS–PAGE and transferred to a PVDF membrane. Membranes were probed with either a mouse anti-NOS2 mAb (BD Biosciences) or polyclonal rabbit antibody to actin (Santa Cruz Biotechnologies, Santa Cruz, CA), followed by incubation with either donkey anti-mouse IgG or goat anti-rabbit conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (Santa Cruz Biotechnologies). Bands were developed using enhanced chemiluminescence following the manufacturer's instructions (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Protein expression was measured by densitometry and normalized against actin.

Leishmania major infection

Leishmania major (World Health Organization strain WHOM/IR/-/173) was maintained by infecting footpads of BALB/c mice. Promastigotes were grown at 26° in M199 medium containing antibiotics, supplemental glutamine and 30% fetal calf serum as described previously until they reached stationary phase.25 Metacyclic promastigotes were incubated with macrophages cultured on eight-chamber tissue culture glass slides (Falcon; BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA; 1 × 105 cells/chamber) at a ratio of six parasites/macrophage. After 6 hr, macrophage monolayers were washed with warm medium to remove extracellular parasites. Thereafter, macrophages were incubated with complete medium containing either a stimulatory anti-CD40 mAb or control mAb, recombinant mouse CD154, recombinant mouse TNF-α, recombinant mouse IFN-γ or LPS (Escherichia coli O55:B5; 100 ng/ml; Sigma Chemical). In certain experiments macrophages were incubated with NG-monomethyl-l-arginine (NMA, 100 μm; Calbiochem, San Diego, CA) before CD40/TNF-α or IFN-γ/TNF-α stimulation. Parasite replication was assessed by light microscopy. Briefly, monolayers were washed 24, 48 and 72 hr after infection followed by fixation and staining with Diff-Quick (Dade Diagnostics, Dade-Behring, Inc., Newark, DE). The percentage of infected macrophages and the number of amastigotes/macrophages were determined by light microscopy by counting at least 200 macrophages/monolayer.

Cell-permeable peptides

Peptides that consisted of the TNFR-associated factors 2,3 (TRAF2,3) and TRAF6 binding sites of CD40 were made cell permeable by using the Kaposi fibroblast growth factor as a protein transduction domain. The CD40-TRAF6 blocking peptide was described previously.26 The sequence for the CD40-TRAF2,3 blocking peptides was NH2-AAVALLPAVLLALLAPSNTAAPVQETLHG-OH. The Kaposi fibroblast growth factor sequence is underlined. Peptides were manufactured by Proteintech Group (San Diego, CA) and were low in endotoxin and > 98% pure by HPLC. Peptides were tested in a mouse cell line that lacks endogenous CD40 (mHEVc).27 Using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen Corporation, Carlsbad, CA), cells were stably transfected with linearized plasmids that encode the extracellular domain of human CD40 and the intracellular domain of mouse CD40 (hmCD40) that have previously described mutations that prevent recruitment of either TRAF2,3 (ΔT2,3) or TRAF6 (ΔT6).28–30 Cells were then transfected with pGL4.32luc2P/NF-κB-RE/Hygro vector (Promega Corporation, Madison, WI), a plasmid that encodes a nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) response element that drives transcription of the luciferase reporter gene luc2P (Photinus pyralis). Cells were selected in culture medium containing hygromycin (100 μg/ml; EMD Chemicals, Gibbstown, NJ) and cloned under limiting dilution. Cells were cultured in a 96-well plate (4 × 104 cells/well) and pre-incubated with peptides for 3 hr followed by stimulation with recombinant human CD154 (3 μg/ml; Amgen). Luciferase activity was assessed using a Steady-Glo luciferase assay system (Promega) and a luminometer.31 Bioluminescence signals were normalized to total protein concentration as determined by BCA protein assay (Pierce Protein Research Products, Rockford, IL). In parallel, the effects of peptides on cell viability were examined using a commercially available AlamarBlue cell viability assay (Invitrogen).

Measurement of nitrite production

Culture supernatants of macrophages were collected 24 hr after incubation with stimulatory anti-CD40 or control mAb with or without TNF-α or with IFN-γ plus TNF-α. The amount of nitrite released was calculated using the Griess reaction (Promega). Data are expressed as μm nitrite.

Statistical analysis

Statistical significance was assessed by Student's t-test and analysis of variance using instat version 3·0 (graphpad, La Jolla, CA).

Results

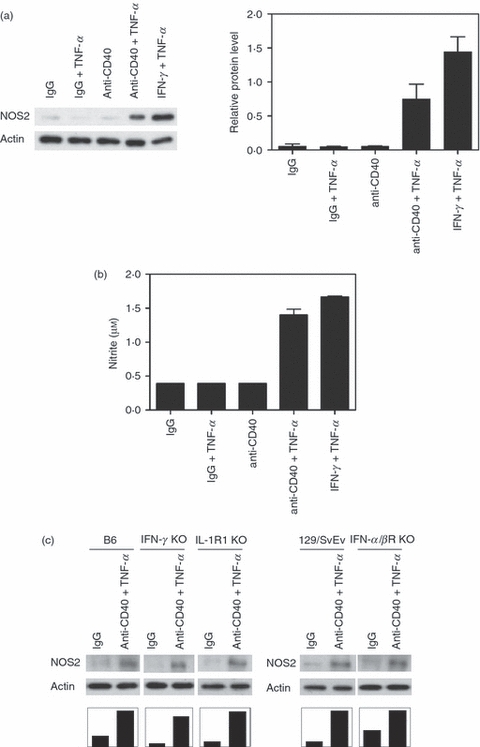

CD40 plus TNF-α signalling co-operate to up-regulate NOS2

We conducted experiments to examine whether CD40 plus TNF-α regulate NOS2 expression. Mouse bone marrow-derived macrophages were incubated with control or an agonistic anti-CD40 mAb with or without TNF-α. IFN-γ/TNF-α was used as positive control. CD40 stimulation co-operated with TNF-α for up-regulation of NOS2 expression as assessed by Immunoblot (Fig. 1a) as well as for nitric oxide production (Fig. 1b). Similar results were obtained regardless of whether macrophages were incubated with a stimulatory anti-CD40 mAb or recombinant CD154 (CD40 ligand, data not shown). Interferons and IL-1 are reported to modulate NOS2 expression and/or nitric oxide production.5,32 However, CD40 and TNF-α appeared to act independently of these cytokines because macrophages from IFN-γ−/−, IFN-α/βR−/− and IL-1R1−/− mice up-regulated NOS2 in response to CD40 stimulation plus TNF-α (Fig. 1c). Taken together, CD40 and TNF-α co-operate to up-regulate NOS2 expression in macrophages.

Figure 1.

CD40 ligation and tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) co-operate to up-regulate inducible nitric oxide synthase (NOS2) and to stimulate nitric oxide production by mouse macrophages. (a, b) Bone marrow-derived macrophages from B6 mice were incubated with isotype control or anti-CD40 monoclonal antibodies (mAb; 10 μg/ml) with or without TNF-α (250 pg/ml) or with interferon-γ (IFN-γ; 100 U/ml) plus TNF-α. Total cell lysates were obtained at 24 hr and used to determine levels of NOS2 and actin by immunoblot (a). (b) Cell-free supernatants were collected 24 hr post-stimulation and were used to measure nitrite concentrations. (c) Bone-marrow-derived macrophages from B6, B129/SvEv, IFN-γ−/−, IFN-α/βR−/− and IL-1R1−/− mice were treated with or without anti-CD40 mAb plus TNF-α. NOS2 and actin expression was assessed by immunoblot. Results of one representative experiment out of three are shown.

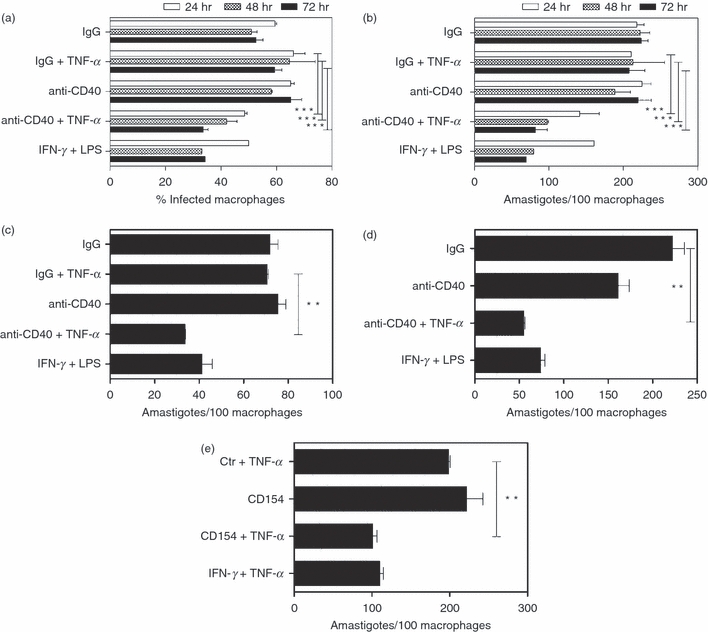

CD40 and TNF-α synergize to induce a NOS2-dependent effector function in macrophages

We examined whether CD40 plus TNF-α not only regulate NOS2 expression but also induce a NOS2-dependent effector function. NOS2 is an important mediator of leishmanicidal activity.19,20 For this reason, we examined the effects of CD40 and TNF-α on the anti-Leishmania activity of macrophages. Bone-marrow-derived macrophages from B6 mice were challenged with promastigotes of L. major followed by incubation with a stimulatory anti-CD40 mAb, control mAb with or without TNF-α. As shown in Fig. 2, neither CD40 stimulation nor TNF-α alone induced anti-L. major activity. In contrast, the combination of CD40 stimulation plus TNF-α resulted in a reduction in both the percentage of infected macrophages and the number of parasites/100 macrophages (Fig. 2a,b). The induction of anti-L. major activity peaked at 48–72 hr after the challenge with the parasites. At these time-points, CD40 plus TNF-α stimulation caused a 48·9 ± 3·7% decrease in the percentage of infected macrophages and a 65·8 ± 9·5% decrease in the number of parasites/macrophages (P < 0·001; n = 4). The decrease in the percentage of infected cells was not caused by selective cell loss in CD40/TNF-α-activated monolayers because cell densities in control and CD40/TNF-α-activated monolayers were similar (not shown). CD40 stimulation also synergized with TNF-α to induce anti-L. major activity in bone marrow-derived macrophages from BALB/c mice (52·0 ± 4·9% reduction in the number of parasites/100 macrophages; P < 0·02, n = 3) (Fig. 2c). In addition, resident peritoneal macrophages from B6 mice exhibited anti-L. major activity in response to CD40/TNF-α stimulation (51·5 ± 2·8% reduction in parasite load; P < 0·02, n = 4) (Fig. 2d). Similar to the results observed with the stimulatory anti-CD40 mAb, incubation with mouse CD154 plus TNF-α resulted in a 46·8 ± 2·3% decrease in the number of parasites/macrophages (P < 0·01; n = 3) (Fig. 2e). Taken together, CD40 synergizes with TNF-α to stimulate anti-L. major activity in mouse macrophages.

Figure 2.

CD40 ligation and tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) co-operate to induce anti-Leishmania major activity of mouse macrophages. Bone-marrow-derived macrophages from B6 mice (a, b) or BALB/c mice (c) were infected with metacyclic promastigotes of L. major followed by incubation with either an agonistic anti-CD40 monoclonal antibody (mAb) or control mAb (10 μg/ml) with or without TNF-α (250 pg/ml). (d) Resident peritoneal macrophages from B6 mice were infected with metacyclic promastigotes of L. major and stimulated as described for bone-marrow-derived macrophages. (e) Bone-marrow-derived macrophages from B6 mice were infected with metacyclic promastigotes of L. major followed by incubation with or without recombinant mouse CD154 (3 μg/ml) in the presence or absence of TNF-α. Monolayers were examined by light microscopy to determine the percentage of infected macrophages (a) as well as the numbers of amastigotes/100 macrophages (b–e). Unless otherwise stated, macrophages were examined at 72 hr post-infection. Results of one representative experiment out of three to four are shown. **P < 0·01; ***P < 0·001.

Next, we examined whether the anti-L. major activity induced by CD40 plus TNF-α is dependent on NOS2. Infected bone-marrow-derived macrophages were incubated with or without the NOS2 inhibitor NMA followed by stimulation with anti-CD40 mAb plus TNF-α or IFN-γ plus TNF-α. As shown in Fig. 3(a), NMA blocked anti-L. major activity induced not only by IFN-γ/TNF-α but also by CD40/TNF-α (94·6 ± 3·6% and 93·4 ± 0·8% inhibition, respectively; n = 3; P < 0·005). To further confirm the role of NOS2 in the anti-L. major activity induced by CD40/TNF-α, we examined macrophages from NOS2−/− mice. In contrast to bone marrow-derived macrophages from wild-type mice, macrophages from NOS2−/− mice failed to acquire anti-L. major activity in response to CD40/TNF-α stimulation (Fig. 3b). Given that IFN-γ is a major regulator of NOS2, we determined if induction of anti-L. major activity triggered by CD40/TNF-α is dependent on IFN-γ. Bone-marrow-derived macrophages from wild-type and IFN-γ−/− mice (BALB/c background) were incubated with anti-CD40 or control mAb with or without TNF-α, or with IFN-γ/TNF-α. As shown in Fig. 3(c), CD40 stimulation plus TNF-α induced anti-L. major activity in macrophages from both wild-type and IFN-γ−/− mice (52·0 ± 6·9% and 49·1 ± 4·9% reduction in number of parasites/macrophages, respectively; n = 3). Moreover, the decrease in parasite load was similar in both groups of mice (P > 0·05; n = 3). Taken together, CD40 and TNF-α co-operate to induce NOS2-dependent anti-L. major activity in macrophages, a response that occurs independently of IFN-γ.

Figure 3.

CD40 ligation plus tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) induce macrophage anti-Leishmania major activity through inducible nitric oxide synthase (NOS2) and independently of interferon-γ (IFN-γ). Bone-marrow-derived macrophages from B6 mice (a) B6/129 or NOS2−/− mice (b) and BALB/c or IFN-γ−/− mice (c) were infected with L. major metacyclic promastigotes followed by incubation with either isotype control or stimulatory anti-CD40 monoclonal antibody (10 μg/ml) with or without TNF-α (250 pg/ml), or with IFN-γ (100 U/ml) plus TNF-α. Certain wells that contained macrophages from B6 mice received NG-monomethyl-l-arginine (NMA; 100 μm) before CD40/TNF-α or IFN-γ/TNF-α stimulation (a). The numbers of amastigotes/100 macrophages were determined by light microscopy at 72 hr. Results of one representative experiment out of three are shown. **P < 0·01.

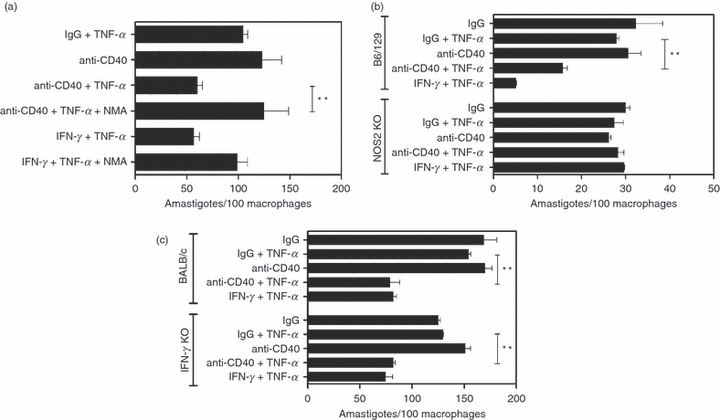

CD40–TRAF6 interaction is required for NOS2 up-regulation

The TRAF proteins are important mediators of the intracellular events induced by CD40. The intracytoplasmic tail of CD40 has binding sites that directly recruit TRAF2 and TRAF3 and another site that directly recruits TRAF6.33–37 CD40 but not TNFR recruits TRAF6.38 It is not known whether CD40 signals through TRAFs to modulate NOS2 expression. Peptides that consist of the amino acid sequence of the TRAF2,3 and TRAF6 binding sites of CD40 block the interaction between CD40 and endogenous TRAFs 26,39 and provide an effective tool to study CD40-TRAF signalling.26 To test the effect of CD40-TRAF signalling in NOS2 expression, macrophages were treated with CD40-TRAF blocking peptides that were made cell permeable by fusing them to Kaposi's fibroblast growth factor transduction domain.26 First, we confirmed that peptides blocked CD40-TRAF signalling using reporter cells that expressed a human–mouse CD40 chimera (extracellular human CD40 and intracellular mouse CD40) that signalled either through the TRAF2,3 binding site (hmCD40 ΔT6) or the TRAF6 binding site (hmCD40 ΔT2,3). Activation of NF-κB is a critical mediator of the cellular effects of CD40-TRAF signalling.12 Hence, these cells were stably transfected with a plasmid that encodes an NF-κB response element that drives transcription of a luciferase reporter gene. Reporter cells were incubated with peptides followed by stimulation with human CD154 and assay of NF-κB activity. The CD40-TRAF2,3 blocking peptide markedly inhibited NF-κB activity in cells that express CD40 that signals through the TRAF2,3 binding site but had no significant effect on cells that express CD40 that signals through the TRAF6 binding site (Fig. 4a). The CD40-TRAF6 blocking peptide had the reverse effect (Fig. 4a). Similar results were obtained with different clones (not shown). The blocking peptides did not exhibit toxicity as assessed by AlamarBlue cell viability assay (not shown). Next, we examined the effects of the peptides on NOS2 up-regulation. Incubation with the CD40-TRAF6 blocking peptide caused a marked inhibition in NOS2 up-regulation induced by CD40-TNF-α (71·1 ± 9·4% inhibition; n = 3; P < 0·01) (Fig. 4b). In contrast, the CD40-TRAF2,3 blocking peptide did not have an appreciable effect on NOS2 up-regulation. Moreover, incubation with the CD40-TRAF6 blocking peptide impaired induction of anti-L. major activity (96·6 ± 2·1% inhibition, n = 3; P < 0·001) whereas the CD40-TRAF2,3 blocking peptide had no significant effect (Fig. 4c). These results suggest that CD40-TRAF6 interaction plays an important role in the up-regulation of NOS2.

Figure 4.

A CD40–tumour necrosis factor receptor-associated factor-6 (TRAF6) blocking peptide inhibits inducible nitric oxide synthase (NOS2) up-regulation in macrophages subjected to CD40 ligation plus tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) stimulation. (a) mHEVc cells stably transfected with a plasmid that encodes a nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) response element that drives transcription of a luciferase reporter gene and either hmCD40 with a mutation in TRAF2,3 binding site (hmCD40 ΔT2,3) or hmCD40 with a mutation in the TRAF6 binding site (hmCD40 ΔT6) were pre-incubated with CD40-TRAF2,3 blocking peptide, CD40-TRAF6 blocking peptide or scrambled peptide (all at 11 μm) or medium alone followed by stimulation with human CD154 (3 μm). Cells were lysed and normalized luciferase reported activity (to total protein) was assessed. Data are expressed as fold-increase in normalized luciferase activity in cells stimulated with CD154 compared with cells treated with respective peptide in the absence of CD154. (b, c) Bone-marrow-derived macrophages from B6 mice were incubated with CD40-TRAF2,3 blocking peptide, CD40-TRAF6 blocking peptide or scrambled peptide (all at 11 μm) before incubation with isotype control or anti-CD40 monoclonal antibody (10 μg/ml) with or without TNF-α (250 pg/ml). (b) Total cell lysates were obtained at 24 hr and used to determine levels of NOS2 and actin by immunoblot. (c) Macrophages were infected with L. major metacyclic promastigotes and the numbers of amastigotes/ 100 macrophages were determined by light microscopy at 72 hr. Results of one representative experiment out of three are shown. ***P < 0·001.

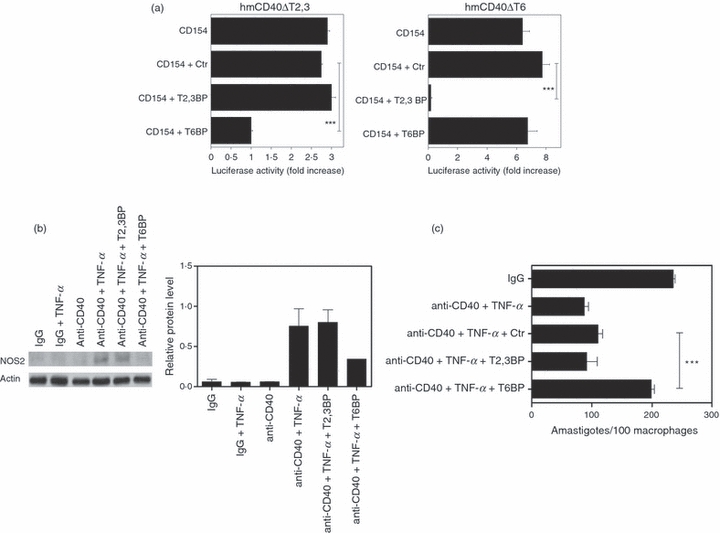

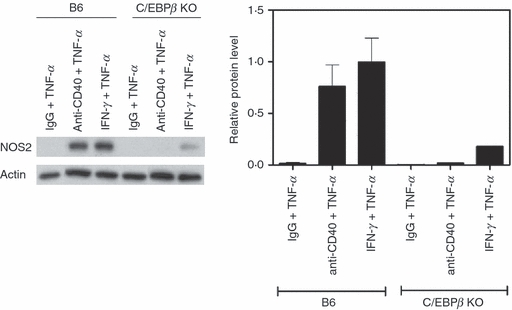

C/EBPβ is required for up-regulation of NOS2 in CD40-TNF-α activated macrophages

The studies described above suggest that TRAF6 downstream of CD40 is required for NOS2 up-regulation. TNF-α but not CD40 has been reported to enhance the activity of the transcription factor C/EBPβ.17,40–43 Moreover, the promoter region of the NOS2 gene has a binding site for C/EBPβ and activation of this transcription factor can promote induction of NOS2.17,44–46 Hence, we examined whether C/EBPβ is required for NOS2 up-regulation in CD40-TNF-α-stimulated macrophages. Bone-marrow-derived macrophages from wild-type mice or C/EBPβ−/− mice were treated with or without TNF-α in the presence or absence of anti-CD40 mAb. As shown in Fig. 5, wild-type but not C/EBPβ−/− macrophages up-regulated NOS2. These results indicate that C/EBPβ is required for NOS2 up-regulation to occur in macrophages that receive TNF-α/CD40 stimulation.

Figure 5.

CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein β (C/EBPβ) is required for inducible nitric oxide synthase (NOS2) up-regulation in macrophages subjected to CD40 ligation plus tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) stimulation. Bone-marrow-derived macrophages from B6 mice or C/EBPβ−/− mice were incubated with isotype control or anti-CD40 monoclonal antibody (10 μg/ml) with or without TNF-α (250 pg/ml). Total cell lysates were obtained at 24 hr and used to determine levels of NOS2 and actin by immunoblot. Results of one representative experiment out of three are shown.

Discussion

NOS2 is involved not only in protection against a variety of pathogens but also in tissue damage in the setting of inflammatory and autoimmune disorders. Hence, regulation of NOS2 should be tight considering its potential harmful effects. We report that CD40 ligation co-operated with TNF-α to up-regulate NOS2 in mouse macrophages. The up-regulation of NOS2 was of functional relevance because it resulted in the acquisition of anti-L. major activity in these cells. Moreover, up-regulation of NOS2 appeared to require the interaction between CD40 and TRAF6, a signalling molecule downstream of CD40 but not TNFR. Finally, C/EBPβ, a transcription factor activated by TNFR but not by CD40 was also required for the up-regulation of NOS2. As CD40 and NOS2 can induce anti-microbial activity in macrophages and are also involved in the development of various chronic inflammatory disorders, these results suggest that the co-operation between CD40 and TNFR and their downstream molecules TRAF6 and C/EBPβ may control CD40–NOS2 dependent anti-microbial activity and inflammation.

It has been reported that neither CD40 nor TNF-α by themselves induces NOS2 and nitric oxide production in macrophages.5,8,9,15–17 Both are found to require the presence of IFN-γ. We report that the combination of CD40 and TNF-α stimulation can supplant the requirement for IFN-γ and result in NOS2 induction. A previous study indicated that treatment of macrophages with CD154 plus TNF-α did not trigger nitric oxide production.16 This result may be explained by suboptimal CD40 ligation because a high degree CD40 multimerization is required for TRAF6-dependent signalling downstream of CD40.47 Relevant to our findings are other reports of co-operation between CD40 and TNF-α. These two pathways are required for induction of autophagy in macrophages48 and they co-operate to prevent apoptosis of B cells stimulated through the B-cell receptor.49 In addition, CD40 stimulation can induce TNF-α production by macrophages. Indeed, it has been reported that endogenous TNF-α is important for nitric oxide production by CD40-stimulated spleen cells.50 We occasionally observed that CD40 stimulation alone could induce weak NOS2 expression in mouse bone-marrow-derived macrophages, an effect that was abrogated by addition of neutralizing anti-TNF-α mAb (Jose-Andres C. Portillo and Carlos S. Subauste, unpublished observations). Whereas our studies indicate that NOS2 up-regulation induced by CD40 and TNF-α can occur in the absence of IFN-γ, it is possible that IFN-γ may modulate the effects of CD40 and TNF-α on NOS2 levels because expression of CD40 and TNF receptors can be increased by IFN-γ.51–53

Co-operation between CD40 and TNFR can be explained by the fact that signalling cascades activated by CD40 and TNFR are not identical.54,55 For example, TRAF6 is directly recruited by CD40 but not TNFR.38 This recruitment is of functional relevance because TRAF6 is a major mediator of CD40 signalling.26,30,56,57 Using peptides that inhibit interaction between TRAFs and the major TRAF binding sites of CD40 (TRAF2,3 and TRAF6 binding sites) our data suggest that CD40–TRAF6 interaction is required for NOS2 expression in macrophages. This would agree with the evidence that TRAF6 is an important mediator of CD40-dependent effector responses in macrophages.26,30,57 Another difference between CD40 and TNFR signalling relates to C/EBPβ. CD40 ligation alone does not activate C/EBPβ.17,43 Instead, CD40 activates NF-κB, a transcription factor through which CD40 regulates NOS2 expression.17 In contrast, TNF-α activates C/EBPβ.40–42 This transcription factor has been reported to be important for expression of NOS2.17,46,58,59 Indeed, in vivo deficiency in C/EBPβ results in lymphoproliferative disorders linked to defective nitric oxide production by splenic macrophages.60 Taken together, the results suggest that TRAF6 and C/EBPβ act downstream of CD40 and TNF-α respectively leading to co-operation and induction of NOS2.

In addition to TNF-α, IFN-γ and LPS can also activate C/EBPβ in macrophages.40,45,46,61–63 Indeed, C/EBPβ is key for NOS2 up-regulation and nitric oxide production by macrophages treated with IFN-γ plus LPS.45,46,60 Consistent with our observation of impaired NOS2 expression in macrophages incubated with IFN-γ plus TNF-α is the demonstration that C/EBPβ is crucial for responses triggered by co-operation between IFN-γ and TNF-α.64 However, our results suggest that NOS2 can still be expressed, albeit at markedly reduced levels, when macrophages are stimulated with IFN-γ and TNF-α. Of potential relevance, while a mutation in the C/EBPβ sequence at the NOS2 promoter abolished promoter activity in RAW 264.7 cells stimulated by LPS plus IFN-γ for 4 hr, promoter activity was unimpaired at 24 hr.46 These and our findings may be explained by the role of various other transcription factors in NOS2 expression including NF-κB, signal transducer and activator of transcription and IFN regulatory factor-1.65–72

CD40 plays an important role in protection against Leishmania both by promoting induction of a type 1 cytokine response and the activation of macrophage anti-Leishmania activity.21–23 In agreement with our findings, CD40 by itself is reported to be insufficient to induce leishmanicidal activity in macrophages 10,22 and unable to induce NOS2 and trigger nitric oxide production in macrophages and microglia.9,15–17 In contrast, CD40 plus IFN-γ trigger nitric oxide production as well as anti-L. major activity.10,22 We show that in the absence of IFN-γ, CD40 and TNF-α co-operate to induce anti-L. major activity that is dependent on NOS2 activation. Leishmania major can modulate the effect of CD40 engagement on macrophages from BALB/c mice.73,74 Although addition of anti-CD40 mAb 6–12 hr after infection caused nitric-oxide-dependent killing of L. major in macrophages from BALB/c mice, the anti-L. major activity was impaired if anti-CD40 was added 24 hr after infection.73 These effects appear to be explained by parasite-dependent manipulation of CD40 signalling in macrophages from BALB/c mice. A strong CD40 signal induces p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase activation and expression of NOS2 and IL-12, whereas a weak CD40 signal induces extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 activation and IL-10 expression.74Leishmania major appears to skew intracellular signalling and as a result, favours extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 activation 74 and promotes IL-10 production,74,75 as well as impairing p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase activation and NOS2 expression in macrophages from BALB/c mice.73,74 Given the differences in outcome based on the strength of CD40 signalling it is important to note that different antibodies to CD40 can induce qualitatively distinct signals depending on the epitope recognized.76,77 Hence, some antibodies lack agonistic activity while others induce different levels of agonism. The agonistic anti-CD40 mAb used in this study has been reported to closely resemble CD154 in terms of functional properties.78 In addition, we confirmed that CD40 and TNF-α co-operate to induce NOS2 and anti-L. major activity in macrophages using CD154, the natural ligand for CD40.

In summary, we report that CD40 and TNF-α co-operate to up-regulate NOS2 in macrophages and induce a NOS2-dependent effector function. Given the role of CD40, TNF-α and NOS2 in the pathogenesis of various inflammatory disorders and in host protection, our findings on CD40/TNF-α-dependent regulation of NOS2 may have implications to a broad variety of diseases.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants EY019250, EY018341, grant 1-2009-204 from the Juvenile Diabetes Foundation International and grants 0555327B and 0755336B from the American Heart Association Ohio Valley Affiliate, all to C.S.S. We thank Maria Hatzoglou and Clifford Harding for providing C/EBPβ−/− and IFN-α/βR−/− mice, respectively.

Disclosures

The authors have no financial disclosures.

References

- 1.MacMicking J, Xie QW, Nathan C. Nitric oxide and macrophage function. Annu Rev Immunol. 1997;15:323–50. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.15.1.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bogdan C. Nitric oxide and the immune response. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:907–16. doi: 10.1038/ni1001-907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wong JM, Billiar TR. Regulation and function of inducible nitric oxide synthase during sepsis and acute inflammation. Adv Pharmacol. 1995;34:155–70. doi: 10.1016/s1054-3589(08)61084-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xie Q-W, Cho HJ, Calaycay J, et al. Cloning and characterization of inducible nitric oxide synthase from mouse macrophages. Science. 1992;256:225–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1373522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ding AH, Nathan CF, Stuehr DJ. Release of reactive nitrogen intermediates and reactive oxygen intermediates from mouse peritoneal macrophages. Comparison of activating cytokines and evidence for independent production. J Immunol. 1988;141:2407–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Drapier JC, Wietzerbin J, Hibbs JB., Jr Interferon-γ and tumor necrosis factor induce the l-arginine-dependent cytotoxic effector mechanism in murine macrophages. Eur J Immunol. 1988;18:1587–92. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830181018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weisz A, Oguchi S, Cicatiello L, Esumi H. Dual mechanisms for the control of inducible-type NO synthase gene expression in macrophages during activation by interferon-γ and bacterial lipopolysaccharide. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:8324–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deng W, Thiel B, Tannenbaum CS, Hamilton TA, Stuehr DJ. Synergistic cooperation between T cell lymphokines for induction of the nitric oxide synthase gene in murine peritoneal macrophages. J Immunol. 1993;151:322–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tian L, Noelle RJ, Lawrence DA. Activated T cells enhance nitric oxide production by murine splenic macrophages through gp39 and LFA-1. Eur J Immunol. 1995;25:306–9. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830250152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nashleanas M, Scott P. Activated T cells induce macrophages to produce NO and control Leishmania major in the absence of tumor necrosis factor receptor p55. Infect Immun. 2000;68:1428–34. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.3.1428-1434.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grewal IS, Flavell RA. CD40 and CD154 in cell-mediated immunity. Annu Rev Immunol. 1998;16:111–35. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.16.1.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van Kooten C, Banchereau J. CD40–CD40 ligand. J Leukoc Biol. 2000;67:2–17. doi: 10.1002/jlb.67.1.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van Kooten C. Immune regulation by CD40–CD40-L interactions – 2; Y2K update. Front Biosci. 2000;5:d880–93. doi: 10.2741/kooten. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Subauste CS. CD40 and the immune response to parasitic infections. Semin Immunol. 2009;21:273–82. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2009.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stout RD, Suttles J, Xu J, Grewal IS, Flavell RA. Impaired T cell-mediated macrophage activation in CD40 ligand-deficient mice. J Immunol. 1996;156:8–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bingaman AW, Pearson TC, Larsen CP. Role of CD40L in T cell-dependent nitric oxide production by murine macrophages. Transpl Immunol. 2000;8:195–202. doi: 10.1016/s0966-3274(00)00026-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jana M, Liu X, Koka S, Ghosh S, Petro TM, Pahan K. Ligation of CD40 stimulates the induction of nitric-oxide synthase in microglial cells. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:44527–33. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106771200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lum H, Buhtoiarov IN, Schmidt BE, Barke G, Paulnock DM, Sondel PM, Rakhmilevich AL. Tumoristatic effects of anti-CD40 mAb-activated macrophages involve nitric oxide and tumor necrosis factor-α. Immunology. 2006;118:261–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2006.02366.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liew FY, Millot S, Parkinson C, Palmer RM, Moncada S. Macrophage killing of Leishmania parasite in vivo is mediated by nitric oxide from l-arginine. J Immunol. 1990;144:4794–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wei X, Charles IG, Smith A, et al. Altered immune response in mice lacking inducible nitric oxide synthase. Nature. 1995;375:408–11. doi: 10.1038/375408a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Campbell KA, Ovendale PJ, Kennedy MK, Fanslow WC, Reed SG, Maliszewski CR. CD40 ligand is required for protective cell-mediated immunity to Leishmania major. Immunity. 1996;4:283–9. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80436-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kamanaka M, Yu P, Yasui T, Yoshida K, Kawabe T, Horii T, Kishimoto T, Kikutani H. Protective role of CD40 in Leishmania major infection at two distinct phases of cell-mediated immunity. Immunity. 1996;4:275–81. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80435-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Soong L, Xu JC, Grewal IS, et al. Disruption of CD40–CD40 ligand interactions results in an enhanced susceptibility to Leishmania amazoniensis infection. Immunity. 1996;4:263–73. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80434-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Andrade RM, Portillo J-AC, Wessendarp M, Subauste CS. CD40 signaling in macrophages induces anti-microbial activity against an intracellular pathogen independently of IFN-γ and reactive nitrogen intermediates. Infect Immun. 2005;73:3115–23. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.5.3115-3123.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kremer IB, Gould MP, Cooper KD, Heinzel FP. Pretreatment with recombinant Flt3 ligand partially protects against progressive cutaneous leishmaniasis in susceptible BALB/c mice. Infect Immun. 2001;69:673–80. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.2.673-680.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mukundan L, Bishop GA, Head KZ, Zhang L, Wahl L, Suttles J. TNF receptor-associated factor 6 is an essential mediator of CD40-activated proinflammatory pathways in monocytes and macrophages. J Immunol. 2005;174:1081–90. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.2.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cook-Mills JM, Gallagher JS, Feldbush TL. Isolation and characterization of high endothelial cell lines derived from mouse lymph nodes. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim. 1996;32:167–77. doi: 10.1007/BF02723682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hsing Y, Hostager BS, Bishop GA. Characterization of CD40 signaling determinants regulating nuclear factor-κB activation in B lymphocytes. J Immunol. 1997;159:4898–906. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jalukar SV, Hostager BS, Bishop GA. Characterization of the roles of TNF receptor-associated factor 6 in CD40-mediated B lymphocyte effector functions. J Immunol. 2000;164:623–30. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.2.623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Andrade RM, Wessendarp M, Portillo J-AC, Yang J-Q, Gomez FJ, Durbin JE, Bishop GA, Subauste CS. TRAF6 signaling downstream of CD40 primes macrophages to acquire anti-microbial activity in response to TNF-α. J Immunol. 2005;175:6014–21. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.9.6014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Csiszar A, Smith KA, Labinskyy N, Orosz Z, Rivera A, Ungvari Z. Resveratrol attenuates TNF-α induced activation of coronary arterial endothelial cells: role of NF-κB inhibition. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;291:H1694–9. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00340.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Geller DA, de Vera ME, Russell DA, Shapiro RA, Nussler AK, Simmons RL, Biliar TR. A central role for IL-1 beta in the in vitro and in vivo regulation of hepatic inducible nitric oxide synthase. IL-1 beta induces hepatic nitric oxide synthesis. J Immunol. 1995;155:4890–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pullen SS, Miller HG, Everdeen DS, Dang TT, Crute JJ, Kehry MR. CD40-tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor (TRAF) interactions: regulation of CD40 signaling through multiple TRAF binding sites and TRAF hetero-oligomerization. Biochemistry. 1998;37:11836–45. doi: 10.1021/bi981067q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Arch RH, Gedrich RW, Thompson CB. Tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factors (TRAFs) – a family of adapter proteins that regulates life and death. Genes Dev. 1998;12:2821–30. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.18.2821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bradley JR, Pober JS. Tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factors (TRAFs) Oncogene. 2001;20:6482–91. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bishop GA, Hostager BS, Brown KD. Mechanisms of TNF receptor-associated factor (TRAF) regulation in B lymphocytes. J Leukoc Biol. 2002;72:19–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wu H, Arron JR. TRAF6, a molecular bridge spanning adaptive immunity, innate immunity and osteoimmunology. Bioessays. 2003;25:1096–105. doi: 10.1002/bies.10352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ishida TK, Mizushima SI, Azuma S, et al. Identification of TRAF6, a novel tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor protein that mediates signaling from an amino-terminal domain of the CD40 cytoplasmic region. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:28745–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.46.28745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tsao DHH, McDonagh T, Telliez J-B, Hsu S, Malakian K, Xu G-Y, Lin L-L. Solution structure of N-TRADD and characterization of the interaction of N-TRADD and C-TRAF2, a key step in the TNFR1 signaling pathway. Mol Cell. 2000;5:1051–7. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80270-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tengku-Muhammad TS, Hughes TR, Ranki H, Cryer A, Ramji DP. Differential regulation of macrophage CCAAT-enhancer binding protein isoforms by lipopolysaccharide and cytokines. Cytokine. 2000;12:1430–6. doi: 10.1006/cyto.2000.0711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yin M, Yang SQ, Lin HZ, Lane MD, Chatterjee S, Diehl AM. Tumor necrosis factor a promotes nuclear localization of cytokine-inducible CCAAT/enhancer protein isoforms in hepatocytes. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:17974–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.30.17974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Robinson CM, Hale PT, Carlin JM. The role of IFN-γ and TNF-α-responsive regulatory elements in the synergistic induction of indoleamine dioxygenase. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2005;25:20–30. doi: 10.1089/jir.2005.25.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jana M, Dasgupta S, Liu X, Pahan K. Regulation of tumor necrosis factor-α expression by CD40 ligation in BV-2 microglial cells. J Neurochem. 2002;80:197–206. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-3042.2001.00691.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Goldring CE, Reveneau S, Algarte M, Jeannin JF. In vivo footprinting of the mouse inducible nitric oxide synthase gene: inducible protein occupation of numerous sites including Oct and NF-IL6. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:1682–7. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.9.1682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dlaska M, Weiss G. Central role of transcription factor NF-IL6 for cytokine and iron-mediated regulation of murine inducible nitric oxide synthase expression. J Immunol. 1999;162:6171–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cieslik K, Zhu Y, Wu KK. Salicylate suppresses macrophage nitric-oxide synthase-2 and cyclo-oxygenase-2 expression by inhibiting CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein-β binding via a common signaling pathway. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:49304–10. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205030200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pullen SS, Labadia ME, Ingraham RH, McWhirter SM, Everdeen DS, Alber T, Crute JJ, Kehry MR. High-affinity interactions of tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factors (TRAFs) and CD40 require TRAF trimerization and CD40 multimerization. Biochemistry. 1999;38:10168–77. doi: 10.1021/bi9909905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Andrade RM, Wessendarp M, Gubbels MJ, Striepen B, Subauste CS. CD40 induces macrophage anti-Toxoplasma gondii activity by triggering autophagy-dependent fusion of pathogen-containing vacuoles and lysosomes. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:2366–77. doi: 10.1172/JCI28796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lens SMA, Tesselaar K, den Drijver BFA, van Oers MHJ, van Lier RAW. A dual role for both CD40-ligand and TNF-α in controlling human B cell death. J Immunol. 1996;156:507–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chaussabel D, Jacobs F, de Jonge J, de Veerman M, Carlier Y, Thielemans K, Gioldman M, Vray B. CD40 ligation prevents Trypanosoma cruzi infection through interleukin-12 upregulation. Infect Immun. 1999;67:1929–34. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.4.1929-1934.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Alderson MR, Armitage RJ, Tough TW, Strockbine L, Fanslow WC, Spriggs MK. CD40 expression by human monocytes: regulation by cytokines and activation of monocytes by the ligand for CD40. J Exp Med. 1993;178:669–74. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.2.669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Boehm U, Klamp T, Groot M, Howard JC. Cellular responses to interferon-γ. Annu Rev Immunol. 1997;15:749–95. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.15.1.749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Calder CJ, Nicholson LB, Dick AD. A selective role for the TNF p55 receptor in autocrine signaling following IFN-γ stimulation in experimental autoimmune uveoretinitis. J Immunol. 2005;175:6286–93. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.10.6286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chung JY, Park YC, Ye H, Wu H. All TRAFs are not created equal: common and distinct molecular mechanisms of TRAF-mediated signal transduction. J Cell Sci. 2002;115:679–88. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.4.679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dempsey PW, Doyle SE, He JQ, Cheng G. The signaling adaptors and pathways activated by TNF superfamily. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2003;14:193–209. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6101(03)00021-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mackey MF, Wang Z, Eichelberg K, Germain RN. Distinct contributions of different CD40 TRAF binding sites to CD154-induced dendritic cell maturation and IL-12 secretion. Eur J Immunol. 2003;33:779–89. doi: 10.1002/eji.200323729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Subauste CS, Andrade RM, Wessendarp M. CD40-TRAF6 and autophagy-dependent anti-microbial activity in macrophages. Autophagy. 2007;3:245–8. doi: 10.4161/auto.3717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Eberhardt W, Pluss C, Hummel R, Pfeilschifter J. Molecular mechanisms of inducible nitric oxide synthase gene expression by IL-1β and cAMP in rat mesangial cells. J Immunol. 1998;160:4961–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gupta AK, Kone BC. CCAAT/enhancer binding protein-β transactivates murine nitric oxide synthase 2 gene in an MTAL cell line. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 1999;276:599–605. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1999.276.4.F599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Screpanti I, Romani L, Musiani P, et al. Lymphoproliferative disorder and imbalanced T-helper response in C/EBPb-deficient mice. EMBO J. 1995;14:1932–41. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07185.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hu J, Roy SK, Shapiro PS, Rodig SR, Reddy SPM, Platanias LC, Schreiber RD, Kalvakolanu DV. ERK1 and ERK2 activate CCAAAT/enhancer-binding protein β-dependent gene transcription in response to IFN-γ. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:287–97. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004885200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Roy SK, Shuman JD, Platanias LC, Shapiro D, Reddy SPM, Johnson PF, Kalvakolanu DV. A role for mixed lineage kinases in regulating transcription factor CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein-b-dependent gene expression in response to interferon-γ. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:24462–71. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413661200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kalvakolanu DV, Roy SK. CCAAT/enhancer binding proteins and interferon signaling pathways. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2005;25:757–69. doi: 10.1089/jir.2005.25.757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Xu G, Zhang Y, Zhang L, Roberts AI, Shi Y. C/EBPβ mediates synergistic upregulation of gene expression by interferon-γ and tumor necrosis factor-α in bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Stem cells. 2009;27:942–8. doi: 10.1002/stem.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Xie Q-W, Whisnant R, Nathan C. Promoter of the mouse gene encoding calcium-independent nitric oxide synthase confers inducibility by interferon gamma and bacterial lipopolysaccharide. J Exp Med. 1993;177:1779–84. doi: 10.1084/jem.177.6.1779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lowenstein CJ, Alley EW, Raval P, Snowman AM, Snyder SH, Russell SW, Murphy WJ. Macrophage nitric oxide synthase gene: two upstream regions mediate induction by interferon γ and lipopolysaccharide. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:9730–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.20.9730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Xie QW, Kashiwabara Y, Nathan C. Role of transcription factor NF-κB/Rel in induction of nitric oxide synthase. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:4705–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kamijo R, Harada H, Matsuyama T, et al. Requirement for transcription factor IRF-1 in NO synthase induction in macrophages. Science. 1994;263:1612–15. doi: 10.1126/science.7510419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Spink J, Evans T. Binding of the transcription factor interferon regulatory factor 1 to the inducible nitric oxide synthase promoter. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:24417–25. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.39.24417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kleinert H, Pautz A, Linker K, Schwarz PM. Regulation of the expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase. Eur J Pharmacol. 2004;500:255–66. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2004.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Farlik M, Reutterer B, Schindler C, Greten F, Vogl C, Muller M, Decker T. Nonconventional initiation complex assembly by STAT and NF-κB transcription factors regulates nitric oxide synthase expression. Immunity. 2010;33:25–34. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Pautz A, Art J, Hahn S, Nowag S, Voss C, Kleinert H. Regulation of the expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase. Nitric Oxide. 2010;23:75–93. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2010.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Awashti A, Mathur R, Khan A, et al. CD40 signaling is impaired in L. major-infected macrophages and is rescued by a p38MAPK activator establishing a host-protective memory T cell response. J Exp Med. 2003;197:1037–43. doi: 10.1084/jem.20022033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mathur RK, Awashti A, Wadhone P, Ramanamurthy B, Saha B. Reciprocal CD40 signals through p38MAPK and ERK-1/2 induce counteracting immune responses. Nat Med. 2004;10:540–4. doi: 10.1038/nm1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Nunes MP, Cysne-Finkelstein L, Monteiro BC, de Souza DM, Gomes NA, DosReis GA. CD40 signaling induces reciprocal outcomes in Leishmania-infected macrophages; roles of host genotype and cytokine milieu. Microbes Infect. 2005;7:78–85. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2004.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bjorck P, Paulie S. CD40 antibodies defining distinct epitopes display qualitative differences in their induction of B-cell differentiation. Immunology. 1996;87:291–5. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1996.428508.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Barr TA, Heath AW. Functional activity of CD40 antibodies correlates to the position of binding relative to CD154. Immunology. 2001;102:39–43. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.2001.01148.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Heath AW, Wu WW, Howard MC. Monoclonal antibodies to murine CD40 define two distinct functional epitopes. Eur J Immunol. 1994;24:1828–34. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830240816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]