Abstract

Reduced plasma levels of high density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol are associated with increased risk for coronary heart disease. Although plasma HDL levels are, in general, inversely related to plasma triglyceride (TG) concentrations, a small proportion of individuals with low HDL cholesterol concentrations have normal plasma TG levels. We wished to determine whether subjects with low plasma levels of HDL cholesterol could be characterized by common abnormalities of lipoprotein metabolism independent of plasma TGs. Therefore, we studied the metabolism of low density lipoprotein (LDL) apolipoprotein B (apo B) and HDL apolipoprotein A-I (apo A-I) in subjects with low plasma HDL cholesterol concentrations with or without hypertriglyceridemia. Nine subjects with low plasma HDL cholesterol levels and normal levels of plasma TGs and LDL cholesterol were studied. Autologous 131I-LDL and 125I-HDL were injected intravenously, and blood samples were collected for 2 weeks. LDL apo B and HDL apo A-I levels were measured by specific radioimmunoassays. Fractional catabolic rates (FCRs, pools per day) and production rates (PRs, milligrams/kilogram · day) for each apolipoprotein were determined. The results were compared with those obtained previously in nine subjects with low plasma HDL cholesterol levels and hypertriglyceridemia and in seven normal subjects. The normal subjects had an HDL apo A-I FCR (mean±SD) of 0.21±0.04. Despite large differences in plasma TG levels, the HDL apo A-I FCRs were similar in the low-HDL, normal-TG group (0.30±0.09) and the low-HDL, high-TG group (0.033±0.10), although only the latter value was significantly increased versus control subjects (p<0.03). Increased apo A-I FCRs were associated with reduced HDL apo A-I levels in both groups of patients. Apo A-I PRs were similar in all groups. In contrast, LDL apo B PR was increased approximately 50% in the low-HDL, normal-TG group (19.3±6.6; p<0.01) compared with normal subjects (12.5±2.6). There was a strong trend toward a greater LDL apo B PR in the low-HDL, high-TG group (17.6±4.5;p=0.06 versus normal subjects) as well. LDL apo B FCRs were similar in all three groups. LDL apo B concentrations were also increased in the group with low HDL cholesterol and normal TG levels. Both groups with low HDL cholesterol levels had cholesterol-depleted LDL and HDL particles. In summary, reduced levels of plasma HDL cholesterol were generally associated with accelerated fractional removal of HDL apo A-I from plasma, increased production of plasma LDL apo B, and evidence of increased cholesteryl ester transfer out of LDL and HDL. The presence of these similar metabolic abnormalities whether or not plasma TG levels were increased suggests that increased apo B production may be a central defect in these patients and that low plasma HDL levels may be closely linked to increased plasma levels of apo B–containing lipoproteins independent of circulating levels of plasma TG.

Keywords: coronary heart disease, HDL, LDL, apolipoprotein B, apolipoprotein A-I, cholesteryl ester transfer protein, reverse cholesterol transport

Reduced plasma concentrations of high density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol have been associated with increased risk for coronary heart disease (CHD) in numerous studies.1–3 Although the inverse association between HDL cholesterol levels and CHD is strong and independent of other known risk factors for CHD, the physiological mechanisms underlying this relation are, as yet, undefined. For example, although the role of HDL in the “reverse cholesterol transport” system has been proposed as the direct link between the concentration of HDL cholesterol and the risk for CHD,4 several other possible roles for HDL as an antiatherogenic lipoprotein have been proposed.5–7 It is also possible that a low HDL cholesterol concentration is only indicative of another abnormality of lipoprotein metabolism that more directly predisposes to CHD.

The common association of low plasma levels of HDL cholesterol with elevated plasma concentrations of triglycerides (TGs)2,3,8,9 provides one possible explanation for HDL cholesterol’s relation to CHD risk. Hence, reduced levels of HDL cholesterol might only be indicative of increased risk for CHD arising from hypertriglyceridemia. This hypothesis, however, is not well supported by epidemiological studies that have implicated plasma TG level as an independent risk factor for CHD in only a minority of studies.10,11 Further insight into the relative roles of HDL and TG in CHD risk might come from studies of individuals with the uncommon, but not rare, combination of low HDL cholesterol and normal plasma TG and low density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol concentrations.

Many patients with isolated reductions in HDL cholesterol concentrations appear to have an increased risk for CHD.12–15 Earlier preliminary data from our laboratory16 and a recent report from Brinton et al17 indicated that these patients can have increased fractional catabolic rates (FCRs) of plasma apolipoprotein A-I (apo A-I). This is the same abnormality in HDL metabolism that is present in subjects with hypertriglyceridemia and low HDL cholesterol levels.16–18 The existence of the same abnormality in apo A-I metabolism in both hypertriglyceridemic and normotriglyceridemic patients with reduced HDL cholesterol levels, together with the demonstration of overproduction of apo B–containing lipoproteins in patients with both hypertriglyceridemia and a strong predisposition to CHD,19–24 led us to propose this hypothesis: Many individuals with low plasma levels of HDL cholesterol have increased production rates (PRs) of apo B–containing lipoproteins whether or not they have concomitant hypertriglyceridemia. We have tested this hypothesis by determining the rates of production of the atherogenic apo B–containing lipoprotein, LDL, in subjects with low plasma HDL cholesterol levels and normal levels of plasma TG and LDL cholesterol. Apo A-I metabolism was also studied in these individuals, and the parameters of LDL and HDL metabolism obtained were compared with those previously reported by us for normal subjects and for subjects with low HDL cholesterol levels and hypertriglyceridemia.16,25,26

Methods

Men identified as having low plasma HDL cholesterol concentrations (below the 25th percentile for age) and normal levels of plasma TG and LDL cholesterol27 before any dietary intervention were recruited from a patient population referred for evaluation to the lipid clinic of the Columbia Specialized Center of Research in Arteriosclerosis. Their individual clinical characteristics are depicted in Table 1. Each of the subjects with low HDL cholesterol and normal plasma TG concentrations was instructed in an American Heart Association (AHA) step 1 diet (30% of calories from fat, 55% of calories from carbohydrate, 15% of calories from protein, and 300 mg cholesterol per day) and had been consuming that diet for at least 6 weeks before the study. None of the subjects had received any lipid-lowering agent or had taken any other medications known to affect plasma lipids for at least 6 weeks before the study. None had any other disease known to affect plasma lipid concentrations. All studies were approved by the Institutional Review Board at the Columbia Presbyterian Medical Center. Subjects gave informed consent before the study. The seven normal subjects and the nine subjects with low plasma HDL cholesterol levels and hypertriglyceridemia were described previously.16,25,26 Their individual clinical characteristics are also included in Table 1. Only four of the normal subjects had HDL apo A-I turnover studies. All normal subjects had LDL apo B turnover studies. All of the hypertriglyceridemic subjects participated in both turnover studies.

Table 1.

Clinical Characteristics

| Group | Age (years) |

%IBW | Clinical history |

|---|---|---|---|

| ↓ HDL-NTG | |||

| 1 | 44 | 116 | S/P inferior MI |

| 2 | 47 | 99 | No CHD |

| 3 | 34 | 95 | S/P anterior MI |

| 4 | 39 | 95 | Father with ↑ TG and CHD |

| 5 | 51 | 109 | S/P carotid endarterectomy |

| 6 | 28 | 128 | Father with CHD |

| 7 | 52 | 88 | Father with ↑ TG |

| 8 | 27 | 100 | Father with ↑ TG and CHD |

| 9 | 31 | 97 | No CHD |

| Mean ± SD | 39.2 ± 9.7 | 103 ± 13 | |

| ↓ HDL- ↑ TG (n = 9) | |||

| 1 | 30 | 126 | |

| 2 | 30 | 92 | |

| 3 | 30 | 95 | |

| 4 | 55 | 103 | |

| 5 | 45 | 119 | |

| 6 | 44 | 112 | |

| 7 | 47 | 99 | |

| 8 | 50 | 126 | |

| 9 | 55 | 140 | |

| Mean ± SD | 42.4 ± 10.3 | 114 ± 16* | |

| Normal subjects (n = 7) | |||

| 1 | 32 | 101 | |

| 2 | 34 | 103 | |

| 3 | 35 | 103 | |

| 4 | 27 | 89 | |

| 5 | 32 | 92 | |

| 6 | 53 | 106 | |

| 7 | 23 | 86 | |

| Mean ± SD | 33.7 ± 9.5 | 97 ± 8 | |

HDL-C, high density lipoprotein cholesterol; ↓ HDL-NTG, low HDL-C with normal plasma triglycerides (TG); ↓ HDL- ↑ TG, low HDL-C with hypertriglyceridemia; IBW, ideal body weight; S/P, status post; MI, myocardial infarction; CHD, coronary heart disease. The ↓ HDL- ↑ TG and normal subjects have been described previously.16,25,26

p < 0.05 vs. normal subjects.

Blood was obtained by venipuncture after a 12–14-hour overnight fast for isolation of lipoproteins. Plasma was isolated by centrifugation at 4°C at 2,000 rpm for 25 minutes. LDL (d, 1.025–1.063) and HDL (d, 1.063–1.210) were isolated by sequential ultracentrifugation.28 These isolations were carried out under sterile conditions. The isolated lipoproteins were iodinated with 131I (for LDL) and 125I (for HDL) by a modification29 of the iodine monochloride method.30 The radiolabeled lipoproteins were passed through 0.22-µm Millipore filters and injected into the study participants within 24 hours of labeling.

The subjects with isolated reductions in HDL cholesterol were admitted to the Irving Center for Clinical Research at the Columbia Presbyterian Medical Center 1–3 days before injection for further diet stabilization. After a fasting sample of blood was obtained, 25 µCi of autologous 131I-LDL and 75 µCi of autologous 125I-HDL were injected intravenously, and blood samples were obtained at 0.5, 1, 2, 6, 12, 24, and 36 hours. The patients were given food after the 2-hour and 12-hour blood samples. Daily fasting blood samples were then obtained during the next 2 weeks.16,25 Patients stayed in the Clinical Research Center for various lengths of time, but all remained in the hospital for at least the first 36 hours after injection of tracers. All subjects received a saturated solution of potassium iodide twice daily starting the day before injection and continuing throughout the study period. The subjects remained on the AHA step 1 diet throughout the protocol. This was verified at frequent meetings between the subject and the research dietitian, at which time 3-day food records were submitted to the research dietitian.

The normal subjects and the subjects with hypertriglyceridemia and reduced HDL cholesterol concentrations were studied at the General Clinical Research Center at the Mount Sinai Medical Center.16,25,26 The general study protocol was essentially identical to that used for the subjects with isolated reductions in HDL cholesterol, except that the previously studied subjects were eating diets containing 40% of calories from fat, 45% of calories from carbohydrate, 15% of calories from protein, and 300 mg cholesterol per day. We have not observed differences in LDL apo B or HDL apo A-I turnover in normal subjects studied while they were eating diets similar to these or eating the AHA step 1 diet (authors’ unpublished data).

At the end of the study, plasma was obtained from each blood sample and subjected to sequential ultracentrifugation to isolate LDL (d, 1.019–1.063) and HDL (d, 1.063–1.210).16,26,28,31 131I–apo B radioactivity in LDL samples was determined by gamma counting, LDL protein concentration was assayed by the method of Lowry et al,32 and LDL apo B specific radioactivity (SA) in each sample was then calculated. An aliquot of each HDL sample was delipidated and redissolved in 6 mol/L urea, and apo A-I was isolated from other apolipoproteins by fast protein liquid chromatography.16,25,33 This protocol was necessary because direct radiolabeling of HDL labels several apolipoproteins. The pooled fractions of pure apo A-I were counted, protein concentration was determined, and 125I-apo A-I SA was calculated. The 131I-apo B SA and 125I-apo A-I SA data were used to estimate LDL apo B and HDL apo A-I FCRs, respectively, using two-pool models for plasma metabolism of these apolipoproteins.16,26,31 Production rates for each apolipoprotein were calculated by multiplying the FCRs by the respective plasma apolipoprotein pool size.

Plasma and lipoprotein lipids were determined by enzymatic methods with an ABA-100 automated spectrophotometer. Plasma HDL cholesterol concentration was measured after precipitation of apo B–containing lipoproteins by dextran sulfate and magnesium. TG and cholesterol concentrations in LDL and HDL were also determined after isolation of these lipoproteins by sequential ultracentrifugation. Our laboratory participates in an ongoing standardization program for measurement of cholesterol and TG, supervised by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Plasma and lipoprotein apo B and apo A-I concentrations were determined by specific fluid-phase radioimmunoassays.16,31,34 Our laboratory participated in the CDC apolipoprotein standardization program.35

The three groups of subjects were compared by analyses of variance followed by specific contrasts between pairs of groups. Multiple regressions of kinetic parameters on plasma lipid and apolipoprotein levels were done by the method of all possible regressions36 using BMDP statistical software. Significance was declared at a value of p=0.05.

Results

The groups were similar in age, with a range of 23–53 years in the normal subjects, 30–55 years in the hypertriglyceridemic subjects, and 27–52 years in the group with isolated reductions in HDL cholesterol (Table 1). The mean ages of the three groups were not statistically different. Only one subject had a body weight that was >30% above ideal according to the original Metropolitan Life Insurance tables. The control subjects and the subjects with only low HDL cholesterol levels had very similar percent ideal body weights. The hypertriglyceridemic group had higher percent ideal body weights, and their mean was significantly greater than that for the normal group. Subjects 1, 3, and 6 in the group with isolated reductions in HDL cholesterol had each been found to be hypertriglyceridemic once in the past according to their medical records. However, each of these three subjects had normal plasma TG levels over periods of 12–24 months on average American diets before entry into this study. Subjects 4, 7, and 8 had never been observed to be hypertriglyceridemic, but each had a parent with elevated plasma TG levels and/or CHD. Subject 6 also had a parent with CHD.

The fasting plasma lipid concentrations of subjects in all three study groups are depicted in Table 2. Plasma total and LDL cholesterol levels were normal in all three groups.27 The ranges and means for LDL cholesterol values were essentially identical for the control and isolated-low-HDL cholesterol groups. Several individuals in both of these groups had LDL cholesterol concentrations that were below the 50th percentile for age. The LDL cholesterol levels in the hypertriglyceridemic subjects tended to be lower than those in the other two groups; this was not unexpected for subjects with marked elevations in plasma TG levels. Plasma TG concentrations were less than the 75th percentile for age27 in the normal subjects and in the subjects with isolated reductions in HDL cholesterol concentrations. The mean±SD TG concentration in the latter group (126.3±38.6 mg/dL) tended to be higher (though not significantly so) than that of the normal group (63.1±8.8 mg/dL). The mean plasma TG level for the hypertriglyceridemic subjects (312.0±101.4 mg/dL) was, as expected, significantly greater than that for either of the other groups. HDL cholesterol levels were less than the 25th percentile for age27 in all subjects in both low-HDL groups, and the mean value for each group was significantly reduced compared with the normal group (51.3±5.5 mg/dL). In addition, HDL levels were reduced in the hypertriglyceridemic group (24.1±7.0 mg/dL) compared with those in the group with isolated reductions in HDL cholesterol (30.1±3.9 mg/dL).

Table 2.

Fasting Plasma Lipids

| Group | TC | TG | LDL-C | HDL-C |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ↓ HDL-NTG | ||||

| 1 | 159 | 144 | 100 | 25 |

| 2 | 185 | 86 | 137 | 30 |

| 3 | 180 | 94 | 125 | 37 |

| 4 | 163 | 122 | 105 | 33 |

| 5 | 153 | 115 | 95 | 34 |

| 6 | 143 | 179 | 78 | 25 |

| 7 | 199 | 173 | 133 | 29 |

| 8 | 208 | 154 | 146 | 29 |

| 9 | 142 | 70 | 98 | 29 |

| Mean ± SD | 170.2 ± 24.0 | 126.3 ± 38.6 | 112.9 ± 22.7 | 30.1 ± 3.9* |

| ↓ HDL- ↑ TG | ||||

| 1 | 205 | 232 | 131 | 30 |

| 2 | 150 | 313 | 61 | 29 |

| 3 | 132 | 313 | 36 | 16 |

| 4 | 180 | 234 | 83 | 36 |

| 5 | 174 | 263 | 61 | 29 |

| 6 | 169 | 216 | 81 | 20 |

| 7 | 269 | 421 | 160 | 21 |

| 8 | 170 | 290 | 63 | 18 |

| 9 | 236 | 526 | 94 | 18 |

| Mean ± SD | 186.1 ± 43.5 | 312.0 ± 101.4* | 85.6 ± 38.5 | 24.1 ± 7.0† |

| Normal subjects | ||||

| 1 | 170 | 66 | 102 | 48 |

| 2 | 162 | 64 | 87 | 60 |

| 3 | 155 | 59 | 91 | 44 |

| 4 | 176 | 58 | 112 | 54 |

| 5 | 208 | 76 | 137 | 51 |

| 6 | 174 | 49 | 117 | 47 |

| 7 | 168 | 70 | 108 | 55 |

| Mean ± SD | 173.3 ± 16.9 | 63.1 ± 8.8 | 107.7 ± 16.8 | 51.3 ± 5.5 |

TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglycerides; LDL-C, low density lipoprotein cholesterol; HDL-C, high density lipoprotein cholesterol; ↓ HDL-NTG, low HDL-C with normal plasma TG; ↓ HDL- ↑ TG, low HDL-C with hypertriglyceridemia.

p < 0.05 vs. normal subjects.

p < 0.05 vs. normal subjects and ↓ HDL-NTG.

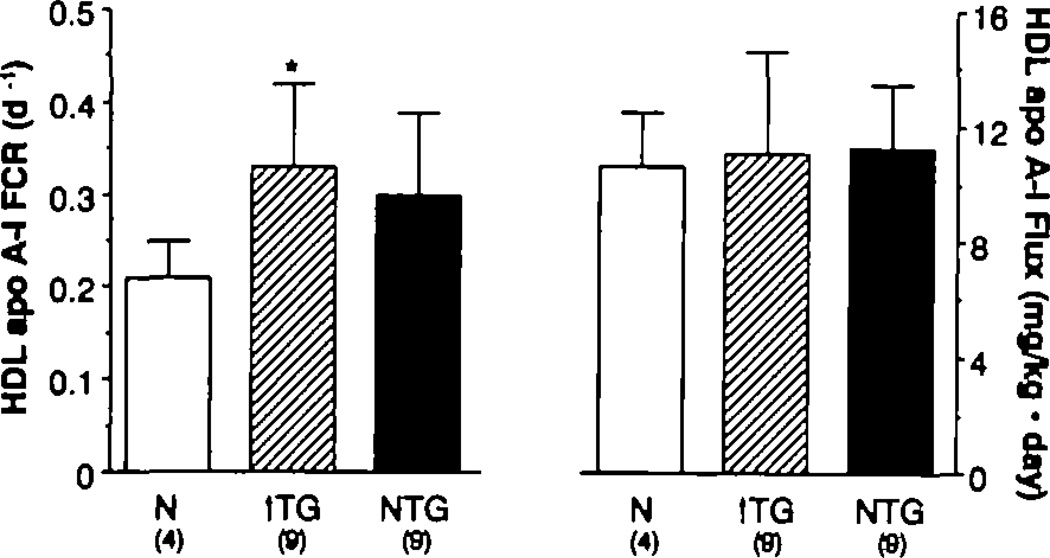

Parameters describing HDL apo A-I metabolism are depicted in Table 3 and Figure 1. The apo A-I FCR (mean±SD, pools per day) was 0.21±0.04 for normal subjects, 0.33±0.10 for hypertriglyceridemic subjects, and 0.30±0.09 for the isolated-low-HDL group. The mean FCR for the hypertriglyceridemic group was significantly greater than that for the normal subjects (p<0.03); the FCR of the isolated-low-HDL group tended to be higher but was not significantly different from the FCR of the control group (p=0.09). Plasma HDL apo A-I concentrations (mean±SD in milligrams per deciliter) were 74.9±19.1 and 62.6±23.7 for the hypertriglyceridemic and isolated-low-HDL groups, respectively, and these values were both reduced (p<0.02 and p< 0.003) compared with the mean apo A-I concentration in the normal group (114.9±38.0). When the FCR of each group was multiplied by the plasma pool of apo A-I, the HDL apo A-I PR could be estimated: The three groups had similar mean PRs.

Table 3.

Metabolic Parameters*

| LDL | HDL | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Apo B | FCR | PR | Apo A-I | FCR | PR |

| ↓ HDL-NTG | ||||||

| 1 | 100.8 | 0.53 | 24.0 | 31.6 | 0.31 | 10.3 |

| 2 | 105.7 | 0.34 | 16.2 | 38.8 | 0.29 | 10.4 |

| 3 | 70.4 | 0.31 | 9.8 | 104.7 | 0.17 | 12.0 |

| 4 | 69.8 | 0.55 | 17.3 | 80.2 | 0.26 | 13.1 |

| 5 | 79.0 | 0.46 | 16.4 | 68.0 | 0.26 | 12.4 |

| 6 | 50.7 | 0.84 | 19.1 | 36.6 | 0.51 | 8.8 |

| 7 | 148.5 | 0.39 | 26.0 | 60.1 | 0.32 | 7.9 |

| 8 | 159.6 | 0.45 | 31.1 | 69.4 | 0.33 | 15.2 |

| 9 | 83.2 | 0.36 | 13.5 | 73.9 | 0.26 | 11.8 |

| Mean ± SD | 96.4 ± 36.7 | 0.47 ± 0.16 | 19.3 ± 6.6 | 62.6 ± 23.7 | 0.30 ± 0.09 | 11.3 ± 2.2 |

| ↓ HDL- ↑ TG | ||||||

| 1 | 96.2 | 0.34 | 14.7 | 78.8 | 0.18 | 6.4 |

| 2 | 65.8 | 0.59 | 17.4 | 113.9 | 0.31 | 15.9 |

| 3 | 65.7 | 0.72 | 21.2 | 88.5 | 0.37 | 14.7 |

| 4 | 62.1 | 0.43 | 12.0 | 59.0 | 0.34 | 9.0 |

| 5 | 77.7 | 0.65 | 22.7 | 73.3 | 0.30 | 9.9 |

| 6 | 77.8 | 0.37 | 12.9 | 45.5 | 0.36 | 7.4 |

| 7 | 75.6 | 0.73 | 24.8 | 76.5 | 0.29 | 10.0 |

| 8 | 56.8 | 0.56 | 14.3 | 71.1 | 0.34 | 10.9 |

| 9 | 62.7 | 0.66 | 18.6 | 67.2 | 0.51 | 15.4 |

| Mean ± SD | 71.2 ± 12.0 | 0.56 ± 0.15 | 17.6 ± 4.5 | 74.9 ± 19.1 | 0.33 ± 0.10 | 11.1 ± 3.5 |

| Normal subjects | ||||||

| 1 | 48.3 | 0.55 | 11.9 | 82.8 | 0.23 | 8.6 |

| 2 | 54.7 | 0.48 | 11.8 | 169.1 | 0.16 | 12.2 |

| 3 | 45.2 | 0.65 | 13.2 | 111.6 | 0.24 | 12.1 |

| 4 | 57.6 | 0.37 | 9.6 | 96.0 | 0.22 | 9.5 |

| 5 | 64.6 | 0.51 | 14.8 | |||

| 6 | 101.0 | 0.37 | 16.8 | |||

| 7 | 57.8 | 0.37 | 9.6 | |||

| Mean ± SD | 61.3 ± 18.6 | 0.47 ± 0.10 | 12.5 ± 2.6 | 114.9 ± 38.0 | 0.21 ± 0.04 | 10.6 ± 1.8 |

LDL, low density lipoprotein; HDL, high density lipoprotein; FCR, fractional catabolic rates; PR, production rates; ↓ HDL-NTG, low HDL cholesterol with normal plasma triglycerides (TG); ↓ HDL- ↑ TG, low HDL cholesterol with hypertriglyceridemia.

Apo B and apo A-I, mg/dL; FCR, pools per day; PR, mg/kg · d.

Figure 1.

Bar graphs showing high density lipoprotein (HDL) apolipoprotein A-I (apo A-I) fractional catabolic rates (FCR) (day−1) (left panel) and production rates (mg/kg · d) (right panel) in normal (N) (open bar), hypertrigfyceridemic (↑ TG)–low-HDL (open-hatched bar), and normal TG–low HDL (dark-shaded bar) groups. Apo A-I FCR was significantly greater in the hypertrigfyceridemic group vs. normal (*p<0.03). There was a trend (p=0.09) toward a greater apo A-I FCR in the group with isolated reductions in HDL. Production rates of apo A-I were similar in all three groups.

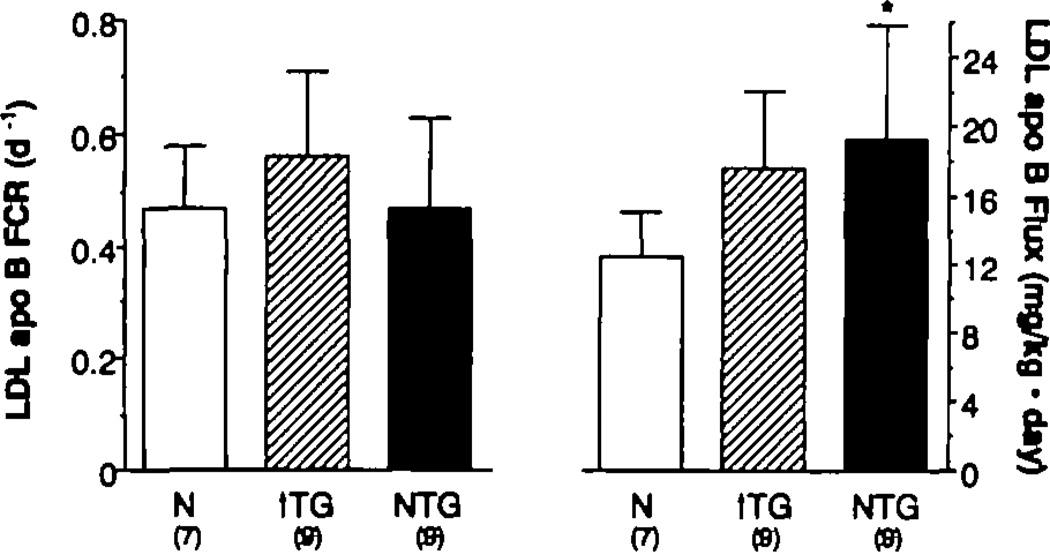

In contrast to the results of the studies of HDL metabolism, the LDL apo B FCRs for the normal, hypertriglyceridemic, and isolated-low-HDL groups were not significantly different from one another (Table 3 and Figure 2). The mean plasma LDL apo B concentration (mean±SD in milligrams per deciliter) was greater in the isolated-low-HDL group (96.4±36.7) than in both the hypertriglyceridemic subjects (71.2±12.0, p<0.05) and the normal subjects (61.3±18.6, p<0.O2). The value of the hypertriglyceridemic group was not greater than that of the normal group. LDL apo B PR (mean±SD in milligrams per kilogram · day) was also significantly greater (p<0.01) in the isolated-low-HDL group (19.3±6.6) compared with the normal subjects (12.5±2.6). The LDL apo B PR of 17.6±4.5 mg/kg · d for the hypertriglyceridemic group tended to be greater than normal as well (p=0.06).

Figure 2.

Bar graphs showing low density lipoprotein (LDL) apolipoprotein B (apo B) fractional catabolic rates (FCR) (day−1) (left panel) and production rates (PR) (mg/kg · day) (right panel) in normal (N) (open bar), hypertrigfyceridemic (↑ TG)–low high density lipoprotein (HDL) (open-hatched bar), and normal TG–low HDL (dark-shaded bar) groups. LDL apo B PR was significantfy greater in the normal TG–low HDL group vs. normal (*p<0.01). LDL apo B PR tended to be greater than normal in the hypertrigfyceridemic group as well (p=0.06). FCRs of apo B were similar in all three groups.

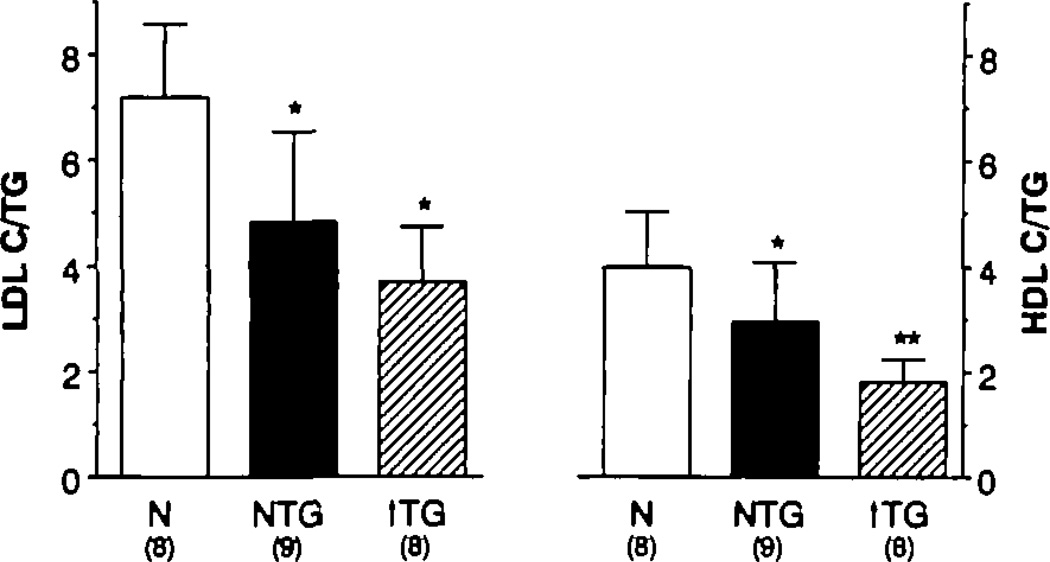

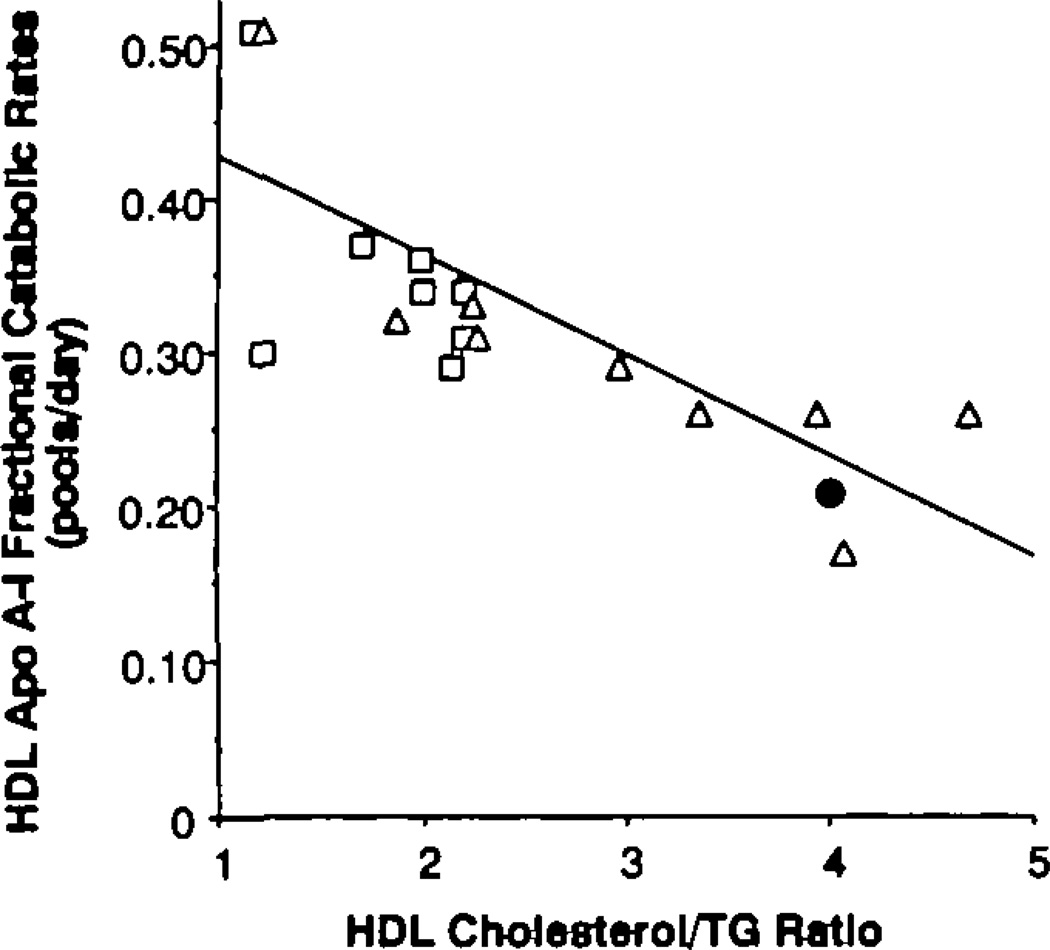

The finding that LDL apo B PR and HDL apo A-I FCR were similarly aberrant in both low-HDL cholesterol groups, despite their markedly different plasma TG levels, suggested that the lipid composition of these lipoproteins might be more similar in the two groups than expected. Compositional analyses of LDL and HDL revealed a graded enrichment of these lipoproteins with TG relative to cholesterol as the plasma TG concentration increased (Table 4 and Figure 3). The cholesterol-to-TG ratio in LDL was significantly reduced in both of the low-HDL groups compared with the ratio present in normal subjects (p<0.003). The ratio of cholesterol to apo B in LDL was also reduced in both groups with low HDL cholesterol levels compared with control subjects (p<0.005). Triglyceride–to–apo B ratios in LDL were similar in both of the low-HDL groups (these data were not available in the control subjects). In HDL, the cholesterol-to-TG ratio followed a similar pattern (Figure 3). In addition, the hypertriglyceridemic group had a cholesterol-to-TG ratio in HDL that was significantly lower than that of the isolated-low-HDL group (p<0.03). The HDL apo A-I FCR was strongly and negatively related (r=−0.75) to the HDL cholesterol–to–TG ratio in the two low-HDL cholesterol groups by univariate analysis (Figure 4). No significant increase in that r value was achieved by adding other measured variables to the regression equation. LDL PR was best described by a regression equation that included the LDL apo B level and the cholesterol-to-TG ratio in HDL (multiple R=0.72).

Table 4.

Lipoprotein Composition

| LDL | HDL | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | C/TG | C/B | TG/B | C/TG |

| ↓ HDL-NTG | ||||

| 1 | 4.54 | 0.99 | 2.18 | 2.27 |

| 2 | 5.19 | 1.29 | 2.49 | 2.96 |

| 3 | 3.48 | 1.77 | 5.09 | 4.07 |

| 4 | 6.50 | 1.51 | 2.31 | 3.93 |

| 5 | 3.75 | 1.20 | 3.20 | 3.36 |

| 6 | 1.95 | 1.53 | 7.91 | 1.21 |

| 7 | 6.04 | 0.89 | 1.47 | 1.88 |

| 8 | 4.40 | 0.91 | 2.07 | 2.25 |

| 9 | 7.60 | 1.18 | 1.55 | 4.68 |

| Mean ± SD | 4.83 ± 1.72 | 1.26 ± 030 | 3.14 ± 2.09 | 2.96 ± 1.15 |

| ↓ HDL- ↑ TG | ||||

| 1 | 3.92 | 1.36 | 3.47 | ND |

| 2 | 3.90 | 0.93 | 2.37 | 2.20 |

| 3 | 2.60 | 0.55 | 2.10 | 1.70 |

| 4 | 5.20 | 1.34 | 2.56 | 2.20 |

| 5 | 2.42 | 0.76 | 3.24 | 1.21 |

| 6 | 3.70 | 1.04 | 2.80 | 1.98 |

| 7 | 4.54 | 2.11 | 4.66 | 2.14 |

| 8 | 4.66 | 1.10 | 2.38 | 1.99 |

| 9 | 2.16 | 1.50 | 6.94 | 1.16 |

| Mean ± SD | 3.68 ± 1.07 | 1.19 ± 0.46 | 3.39 ± 1.45 | 1.82 ± 0.43 |

| Normal subjects | ||||

| 1 | 5.36 | 1.18 | 3.04 | |

| 2 | 6.18 | 2.11 | 3.76 | |

| 3 | 5.56 | 1.59 | 3.56 | |

| 4 | 7.26 | 2.01 | 3.13 | |

| 5 | 8.55 | 1.94 | 5.60 | |

| 6 | 7.25 | 2.12 | 3.23 | |

| 7 | 8.90 | 1.15 | 5.75 | |

| 8 | 8.60 | 1.86 | 3.78 | |

| Mean ± SD | 7.21 ± 1.40 | 1.83 ± 0.34 | 3.98 ± 1.08 | |

LDL, low density lipoprotein; HDL, high density lipoprotein; C/TG, cholesterol to triglyceride (TG) ratio (wt/wt) in LDL and HDL; C/B, cholesterol to apolipoprotein B (apo B) ratio (wt/wt) in LDL; TG/B, TG to apo B ratio (wt/wt) in LDL; ↓ HDL-NTG, low HDL cholesterol with normal plasma TG; ↓ HDL- ↑ TG, low HDL cholesterol with hypertriglyceridemia.

As noted in legends of Figures 3 and 4, LDL and HDL TG concentrations were not determined in the normal subjects who had turnover studies. The normal LDL C/B ratios are from the subjects who had turnover studies, and the normal LDL and HDL C/TG ratios are from a group of comparable normal subjects.

Figure 3.

Bar graphs showing cholesterol/trigfyceride (TG) ratio in low density lipoprotein (LDL) (left panel) and high density lipoprotein (HDL) (right panel) in each group of subjects. The normal (N) subjects in whom we performed turnover studies did not have HDL and LDL TG concentrations measured. Therefore, we present ratio data for a separate group of normal subjects for whom we have compositional but not kinetic data. Both low-HDL groups had cholesterol-depleted LDL vs. normal (*p<0.003). Both low-HDL groups had cholesterol-depleted HDL vs. normal (*p<0.04 for normal TG–low HDL vs. normal and *p<0.001 for hypertrigfyceridemic [↑ TG] –low HDL vs. normal). In addition, HDL in the hypertrigfyceridemic group was more cholesterol depleted than the HDL in the normal TG–low HDL group (**p<0.03).

Figure 4.

Graph showing relation between high density lipoprotein (HDL) apolipoprotein A-I (apo A-I) fractional catabolic rates (FCR) (y axis) and HDL cholesterol/trigfyceride (TG) ratio (x axis) for the hypertrigfyceridemic–low HDL (□;) and normal TG–low HDL (∆) subjects. The normal subjects who had onfy turnover studies had a mean FCR of 0.21; the normal subjects who had onfy cholesterol/trigfyceride ratios (Figure 3) had a mean ratio of 4. The combination of these two means (●) falls very close to the regression line.

Discussion

In this study we have observed that individuals with isolated reductions of plasma HDL cholesterol concentrations have several characteristics of lipoprotein metabolism and composition similar to those frequently seen in subjects with both hypertrigryceridemia and low HDL cholesterol levels. Because of the strong relation between hypertriglyceridemia and low plasma HDL levels,2,3,8,9 most previous studies of HDL metabolism have focused on individuals with both of these lipid abnormalities, and accelerated fractional catabolism of apo A-I has been well documented in most subjects with low plasma apo A-I concentrations and hypertriglyceridemia.18 Our results, which indicated a trend toward higher FCRs for HDL apo A-I in the subjects with isolated reductions in HDL cholesterol, are in harmony with those of Brinton et al17 and with the results of a recent study by Gylling et al.37 Taken together, the results of these studies suggest that many patients with low HDL cholesterol levels and normal plasma TG concentrations also have an increased apo A-I FCR.

We also found that subjects with isolated reductions in HDL cholesterol concentrations commonly had increased rates of production of LDL apo B. This is an observation not previously reported, although numerous studies have demonstrated increased rates of production of apo B, the major structural protein in very low density lipoproteins (VLDL), intermediate density lipoproteins (IDL), and LDL, in most subjects with hypertriglyceridemia.19–24,31,38 Familial combined hyperlipidemia (FCHL)39 and hyperapobetalipoproteinemia (hyperapo B)40 are dyslipidemic syndromes characterized by overproduction of apo B–containing lipoproteins.19–21 Although elevated plasma apo B concentrations are consistent abnormalities in those two disorders, hypertriglyceridemia is variable.40–42 Kissebah et al43 demonstrated overproduction of apo B in subjects with FCHL during paired studies when they had hypertriglyceridemia compared with when they did not have hypertriglyceridemia. Reduced levels of HDL cholesterol are common in patients with either FCHL or hyperapo B,19–21,40,43,44 and these reductions can persist even when plasma TG concentrations are reduced to the normal range. Although we determined only the rate of production of LDL apo B and not VLDL and IDL apo B, there is no reason to believe that increased conversion of VLDL and/or IDL to LDL was the basis of the increased LDL apo B PRs in our subjects with isolated low HDL levels. In addition, we have preliminary data from a separate group of subjects with isolated reductions in HDL cholesterol that indicate that they have increased plasma concentrations of VLDL and IDL apo B.45 Of course, only studies that determine total apo B production can definitively address this issue.

The subjects with isolated reductions in HDL cholesterol were compared with “historical” groups of normal subjects and subjects with both hypertriglyceridemia and low HDL. One difference between the experimental protocol used in the new studies and those carried out previously16,25,26 was the diet consumed by the subjects. Although the present group with isolated reductions in HDL cholesterol followed a step 1 diet and both the control and the hypertrigryceridemic subjects ate average American diets, we do not believe that these dietary differences had a significant effect on the study outcome. First, we have not been able to demonstrate differences in either LDL apo B or HDL apo A-I turnover in normal subjects eating these two diets (authors’ unpublished observation). Second, a review of the literature indicates that consumption of a lower-fat diet would, if it had any significant effect, decrease LDL apo B PR. Such an effect would tend to minimize the true difference between our “historical” control subjects and the subjects with isolated low HDL.

Our control subjects tended to be younger than either of the groups with low HDL cholesterol levels, although there were no significant differences in the mean ages of the three groups. Ericsson et al46 recently reported decreases in LDL apo B FCRs as age increased in a group of normal men. However, age accounted for < 16% of the variance in FCR for the entire group, and when the subjects in that study were subgrouped as young (mean age, 28±1 years), middle-aged (48±2 years), and elderly (68±2 years), there was no difference between the FCRs in the young and the middle-aged groups. Since all of our subjects fell into the range of the young and middle-aged men studied by Ericsson et al, we believe that slight age differences played no role in the differences in LDL apo B PRs that we observed between our control subjects and the groups with low HDL cholesterol levels. Indeed, the mean LDL apo B PR of our control subjects was essentially the same as those reported by several other groups.21–24,46

Our findings indicate that both overproduction of apo B-containing lipoproteins and accelerated fractional catabolism of apo A-I may be present in individuals who have low plasma levels of HDL cholesterol, with or without concomitant elevations of plasma TG. Fidge et al47 were the first to carry out simultaneous studies of apo A-I and apo B metabolism. Although their methods of analyzing kinetic data differed from ours, it is interesting to note that they found an inverse relation between apo A-I mass and FCR (r= −0.48) that was similar to the relation we observed between those two parameters (r= −0.57). In contrast to our study, in which we observed an inverse relation between HDL apo A-I FCR and LDL PR (r= −0.37; P=0.09), they found no relation between either VLDL or LDL PR and HDL apo A-I FCR. Fidge et al47 did not study subjects with isolated reductions in HDL cholesterol. In a study by Kesaniemi et al,23 LDL apo B PRs were about 20 mg/kg · d in a group of normotriglyceridemic men with CHD and 13 mg/kg · d in normal subjects. Although the mean HDL cholesterol level of 44 mg/dL in the coronary patients in that study was much higher than those in our group with isolated low HDL, it is important to note that the mean HDL cholesterol concentration of the control subjects in that study was 54 mg/dL. Thus, there was a 10-mg/dL difference in HDL cholesterol levels between the groups, and the subjects with the lower HDL levels had significantly higher LDL apo B PRs. In a more recent study, Vega et al24 determined LDL apo B PRs in a group of men with coronary disease who were divided into those with and those without hypertriglyceridemia. All of the hypertriglyceridemic subjects had high LDL apo B PRs. Of the 18 individuals with normal plasma TG and low plasma HDL cholesterol levels, six had elevated rates of LDL apo B production and 12 had normal LDL apo B PRs. Thus, some, but clearly not the majority, of those patients with isolated low HDL had metabolic patterns similar to those of our subjects. All of the individuals studied by Vega et al24 had coronary disease, many smoked, and some were receiving treatment with β-blockers. The distribution of these potentially confounding factors between the two groups of subjects with isolated low HDL was not reported by the authors, but the presence of these factors in many of the subjects could explain some of the differences between their results and ours.

The pathophysiological basis for the high apo A-I FCR in subjects with both hypertriglyceridemia and low HDL cholesterol levels is incompletely defined. However, cholesteryl ester transfer protein (CETP)–mediated transfer of HDL cholesteryl ester for VLDL/IDL TG, followed by hydrolysis of the TG-rich HDL, is thought to play an important role in regulating apo A-I catabolism. Thus, accelerated CETP-mediated core lipid exchange, driven by increased levels of VLDL TG and followed by hydrolysis of a TG-enriched HDL core, could reduce the binding affinity of apo A-I for the particle,48 making available “free” apo A-I for removal by the kidney.49–51 The link between altered HDL core lipid composition (and/or particle size) and apo A-I catabolism is indicated by the strong correlation between the cholesterol-to-TG ratio in HDL and the FCR of apo A-I in the present study.

Although CETP-mediated exchange of cholesteryl ester for TG is clearly accelerated in hypertriglyceridemia,52–53 our observation that HDL from the subjects with isolated reductions in HDL cholesterol was relatively TG enriched suggests that increased exchange of HDL and VLDL/IDL core lipids also occurred in that group. Further evidence in support of increased exchange of cholesteryl ester for TG in the group with isolated low HDL can be found in the decreased LDL cholesterol–to–apo B ratios, the decreased LDL cholesterol–to–TG ratios, and the increased LDL TG–to–apo B ratios in those subjects. In fact, the abnormalities of LDL core lipid composition were nearly identical in both groups with low HDL cholesterol, despite markedly different TG levels. We believe that these abnormalities in lipoprotein composition are indicative of increased CETP-mediated core lipid exchange that is stimulated by increased numbers of TG-rich lipoprotein particles, even though the absolute level of plasma TG is normal. As noted earlier, we have preliminary data in a separate group of subjects with isolated low HDL cholesterol, indicating that they have elevations in VLDL and IDL apo B levels that are similar to those present in hypertriglyceridemic subjects.

It should be noted that the LDL compositional abnormalities we have observed in our group with isolated reductions in HDL cholesterol concentrations suggest that they have small, dense, “atherogenic” LDL as described by Austin et al.54 Those authors have noted the close association of these LDL characteristics with elevated levels of VLDL TG and reduced plasma concentrations of HDL cholesterol. Small, cholesteryl ester–depleted LDL has also been found to be characteristic of individuals with FCHL and/or hyperapo B.55 The fact that several of our patients had had elevated TG levels in the past and/or a family history of hypertriglyceridemia suggests that some of them may have normolipidemic (exclusive of HDL cholesterol) variants of those syndromes. For example, some of our patients may have been able to maintain normal TG levels despite overproduction of apo B–containing lipoproteins because of long-term efforts to maintain lower body fat or better cardiovascular fitness. Lower rates of synthesis and secretion of VLDL TG (or more efficient lipolysis) may be all that separates our subjects with isolated reductions of HDL from our subjects with hypertriglyceridemia and low HDL cholesterol. The ability to maintain reduced hepatic VLDL TG production without significantly decreasing overall rates of secretion of apo B–containing lipoproteins is consistent with data supporting independent regulation of TG and apo B secretion by the liver.31,43,56 It is also consistent with the evidence for “direct” secretion of LDL apo B in subjects with FCHL and hyperapo B,20,21,44 particularly when they have normal TG levels.

Do these findings fit into an epidemiological model in which HDL plays a protective role vis-à-vis CHD? A good deal of evidence obtained from studies in animals,4 and more recently in humans,57 indicates that the “reverse cholesterol transport” system initially involves movement of cellular free cholesterol to HDL, where it is esterified.58 Much of the HDL cholesteryl ester is then transferred, via a CETP-mediated process,59 to apo B–containing lipoproteins. These include VLDL and IDL in fasting plasma and chylomicrons and their remnants during the postprandial period. Indeed, there is evidence in humans that the direct delivery of cholesteryl esters to the liver by HDL is negligible in humans.60 Thus, the final and key step in “reverse cholesterol transport” may be the internalization of apo B–containing lipoproteins by hepatocytes.4 Since epidemiological evidence indicates that low levels of plasma apo B and high levels of plasma HDL cholesterol are associated with reduced CHD, we propose that the final step in “reverse cholesterol transport,” i.e., the targeting of cholesteryl ester to the liver, functions maximally when the plasma concentration of apo B–containing lipoprotein acceptors for HDL cholesteryl esters is low. Hence, although a small pool of apo B–containing lipoproteins could limit the rate of transfer of HDL cholesteryl esters (resulting in a high plasma concentration of HDL cholesterol), it would ensure preferential final delivery of those cholesteryl esters to the liver.

In contrast, individuals with elevated concentrations of apo B–containing lipoproteins (with or without absolute increases in TG levels) could have accelerated CETP-mediated transfer of HDL cholesteryl esters to those particles. Increased core lipid exchange would both reduce HDL cholesterol levels and increase fractional catabolism of apo A-I,51 resulting in reduced numbers of HDL particles. Concomitant changes in core lipid composition of apo B–containing lipoproteins could increase their atherogenicity: VLDL would become cholesteryl ester enriched and LDL would become small, dense, and cholesteryl ester depleted. We cannot, of course, rule out the possibility that accelerated CETP-mediated transfer of HDL cholesteryl ester to apo B–containing lipoproteins might also disrupt the direct delivery of that lipid to hepatocytes61 and/or reduce the ability of HDL to be antiatherogenic by other mechanisms.5–7

In summary, we have demonstrated that individuals with isolated reductions in plasma HDL cholesterol levels commonly have increased rates of production of apo B–containing lipoproteins. This group of patients may, therefore, be related to individuals with either FCHL38 or hyperapo B.39 They also have the atherogenic LDL phenotype.54 The present results add to previous studies that suggest that increased hepatic secretion of apo B–containing lipoproteins is associated with increased risk for CHD.19–24

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Nora Ngai, Jimmy Lopez, and Minnie Myers for their excellent technical assistance and the nurses of the Irving Center for Clinical Research for assistance with blood drawing. We also wish to thank Wahida Karmally and the diet staff of the Irving Center for Clinical Research for their help.

Supported by grants HL-36000, HL-21006, and RR-645 from the National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

References

- 1.Miller GJ, Miller NE. Plasma high density lipoprotein concentration and development of ischaemic heart disease. Lancet. 1975;1:16–19. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(75)92376-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rhoads GG, Gulbrandsen CL, Kagan A. Serum lipoproteins and coronary heart disease in a population study of Hawaiian Japanese men. N Engl J Med. 1976;294:292–298. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197602052940601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gordon T, Castelli WP, Hjortland MC, Kannel WB, Dawber TR. High density lipoprotein as a protective factor against coronary heart disease. Am J Med. 1977;62:707–714. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(77)90874-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reichl D, Miller NE. Pathophysiology of reverse cholesterol transport: Insights from inherited disorders of lipoprotein metabolism. Arteriosclerosis. 1989;9:785–797. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.9.6.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bernard DW, Rodriguez A, Rothblat GH, Glick JM. Influence of high density lipoprotein on esterified cholesterol stores in macrophages and hepatoma cells. Arteriosclerosis. 1990;10:135–144. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.10.1.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parthasarathy S, Barnett J, Fong LG. High-density lipoprotein inhibits the oxidative modification of low-density lipoprotein. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1990;1044:275–283. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(90)90314-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pomerantz KB, Fleisher LN, Tall AR, Cannon PJ. Enrichment of endothelial cell arachidonate by lipid transfer from high density lipoproteins: Relationship to prostaglandin I2 synthesis. J Lipid Res. 1985;26:1267–1276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davis CE, Gordon D, LaRosa J, Wood PDS, Halperin M. Correlations of plasma high density lipoprotein cholesterol levels with other plasma lipid and lipoprotein concentrations. Circulation. 1980;62 suppl IV:IV-24–IV-30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Albrink MJ, Krauss RM, Lindgren FT, Von Der Groeben VD, Wood PD. Intercorrelations among high density lipoprotein, obesity, and triglycerides in a normal population. Lipids. 1980;15:668–678. doi: 10.1007/BF02534017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hulley SB, Rosenman RH, Bawol RD, Brand RJ. Epidemiology as a guide to clinical decisions: The association between triglyceride and coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med. 1980;3O2:1383–1389. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198006193022503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Austin MA. Plasma triglyceride and coronary heart disease. Arterioscler Thromb. 1991;11:2–14. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.11.1.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moberg B, Wallentin L. High density lipoprotein and other lipoproteins in normolipidaemic and hypertriglyceridaemic (type IV) men with coronary artery disease. Eur J Clin Invest. 1981;11:433–440. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.1981.tb02010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wallentin LW, Sundin B. HDL2 and HDL3 lipid levels in coronary artery disease. Atherosclerosis. 1985;59:131–136. doi: 10.1016/0021-9150(86)90041-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Franceschini G, Bondioli A, Granata D, Mercun V, Negri M, Tosi C, Sirton CR. Reduced HDL2 levels in myocardial infarction patients without risk factors for atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis. 1987;68:213–219. doi: 10.1016/0021-9150(87)90200-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schaefer EJ, McNamara JR, Genest J, Jr, Ordovas JM. Genetics and abnormalities in metabolism of lipoproteins. Clin Chem. 1988;34:B9–B12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Le NA, Ginsberg HN. Heterogeneity of apolipoprotein AI turnover in subjects with reduced concentrations of plasma high density lipoprotein cholesterol. Metabolism. 1988;37:614–617. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(88)90077-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brinton EA, Eisenberg S, Breslow JL. Increased apo A-I and apo A-II fractional catabolic rate in patients with low high density lipoprotein-cholesterol levels with or without hypertriglyceridemia. J Clin Invest. 1991;87:536–544. doi: 10.1172/JCI115028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nicoll A, Miller NE, Lewis B. Advances in Lipid Research. Vol 17. New York: Academic Press, Inc; 1980. High density lipoprotein metabolism; pp. 54–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chait A, Albers JJ, Brunzell JD. Very low density lipoprotein overproduction in genetic forms of triglyceridemia. Eur J Clin Invest. 1980;10:161–172. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.1980.tb00004.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kissebah AH, Alfarsi A, Adams PW. Integrated regulation for very low density lipoprotein triglyceride and apolipoprotein-B kinetics in man: Normolipidemic subjects, familial hypertriglyceridemia and familial combined hyperlipidemia. Metabolism. 1981;20:856–868. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(81)90064-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Teng B, Sniderman AD, Soutar AK, Thompson GR. Metabolic basis of hyperapobetalipoproteinemia: Turnover of apolipoprotein B in low density lipoprotein and its precursors and subtractions compared with normal and familial hypercholesterolemia. J Clin Invest. 1986;77:663–672. doi: 10.1172/JCI112360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kesaniemi YA, Beltz WF, Grundy SM. Comparison of metabolism of apolipoprotein B in normal subjects, obese patients and patients with coronary heart disease. J Clin Invest. 1985;76:586–595. doi: 10.1172/JCI112010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kesaniemi YA, Grundy SM. Overproduction of low density lipoproteins associated with coronary heart disease. Arteriosclerosis. 1983;3:40–46. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.3.1.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vega GL, Beltz W, Grundy SM. Low density lipoprotein metabolism in hypertrigryceridemic and normolipidemic patients with coronary heart disease. J Lipid Res. 1985;26:115–126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Le N-A, Gibson JC, Ginsberg HN. Independent regulation of plasma apolipoprotein CII and CIII concentrations in very low density and high density lipoproteins: Implications for the regulation of the catabolism of these lipoproteins. J Lipid Res. 1989;29:669–677. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ginsberg H, Goldberg IJ, Wang-Iverson P, Gitler E, Le N-A, Gilbert HS, Brown WV. Increased catabolism of native and cyclohexanedione-modified low density lipoprotein in subjects with myeloproliferative diseases. Arteriosclerosis. 1983;3:233–241. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.3.3.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.The Lipid Research Clinics Program Epidemiology Committee. Plasma lipid distributions in selected North American populations: The Lipid Research Clinics Program Prevalence Study. Circulation. 1979;60:427–439. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.60.2.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Havel RJ, Eder HA, Bragdon JH. The distribution and chemical composition of ultracentrifugally separated lipoproteins in human serum. J Clin Invest. 1955;4:1345–1353. doi: 10.1172/JCI103182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bilheimer D, Eisenberg S, Levy RI. The metabolism of very low density lipoprotein protein: I. Preliminary in vitro and in vivo observations. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1972;260:212–221. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(72)90034-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McFarlane AS. Efficient trace labeling of proteins with iodine. Nature (Lond) 1958;182:53–57. doi: 10.1038/182053a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ginsberg HN, Le N-A, Gibson JC. Regulation of the production and catabolism of plasma low density lipoproteins in hypertriglyceridemic subjects: Effect of weight loss. J Clin Invest. 1985;75:614–623. doi: 10.1172/JCI111739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lowry OH, Rosenbrough NJ, Farr AL, Randall RJ. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951;193:265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Polacek D, Edelstein C, Scanu AM. Rapid fractionation of human high density apolipoproteins by high performance liquid chromatography. Lipids. 1981;16:927–929. doi: 10.1007/BF02534999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gibson JC, Rubenstein A, Bukberg PR, Brown WV. Apolipoprotein E-enriched lipoprotein subclasses in normolipidemic subjects. J Lipid Res. 1983;24:886–898. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Smith SJ, Cooper GR, Henderson LO, et al. An international collaborative study on standardization of apolipoproteins A-I and B. Clin Chem. 1988;33:2240–2249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Draper NR, Smith H. Applied Regression Analysis. ed 2. New York: Wiley-Interscience; 1981. pp. 296–302. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gylling H, Vega GL, Grundy SM. Physiologic mechanisms for reduced apolipoprotein A-I concentrations associated with low levels of high density lipoprotein cholesterol in patients with normal plasma lipids. J Lipid Res. 1992;33:1527–1539. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grundy SM, Vega GL. Hypertriglyceridemia: Causes and relation to coronary heart disease. Semin Thromb Hemost. 1988;14:149–164. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1002769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Goldstein JL, Schrott HG, Hazzard WR, Bierman EL, Motulsky AG. Hyperlipidemia in coronary heart disease: II. Genetic analysis in 176 families and delineation of a new inherited disorder, combined hyperlipidemia. J Clin Invest. 1973;52:1544–1568. doi: 10.1172/JCI107332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sniderman A, Wolfson C, Teng B, Franklin FA, Bachorik PS, Kwiterovich PO. Association of hyperapobetalipoproteinemia with endogenous hypertriglyceridemia and atherosclerosis. Ann Intern Med. 1982;97:833–839. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-97-6-833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Grundy SM, Chait A, Brunzell JD. Familial combined hyperlipidemia workshop. Arteriosclerosis. 1987;7:203–207. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brunzell JD, Sniderman A, Albers JJ, Kwiterovich PO., Jr Apoproteins B and A-1 and coronary artery diseases in humans. Arteriosclerosis. 1984;4:79–83. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.4.2.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kissebah AH, Alfarsi S, Evans DJ. Low density lipoprotein metabolism in familial combined hyperlipidemia: Mechanism of the multiple lipoprotein phenotypic expression. Arteriosclerosis. 1984;4:614–624. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.4.6.614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Arad Y, Ramakrishnan R, Ginsberg HN. Lovastatin therapy reduces low density lipoprotein apoB levels in subjects with combined hyperlipidemia by reducing the production of apoB-containing lipoproteins: Implications for the pathophysiology of apoB production. J Lipid Res. 1990;31:567–582. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ginsberg HN, Ngai C, Johnson J, Cocke T, Holleran S, Tall A, Ramakrishnan R. Subjects with hypoalphalipoproteinemia have increased apoB-containing lipoproteins and abnormal cholesteryl ester metabolism. Circulation. 1992;86 suppl I:I-72. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ericsson S, Eriksson M, Vitols S, Einarsson K, Berglund L, Angelin B. Influence of age on the metabolism of plasma low density lipoproteins in healthy males. J Clin Invest. 1991;87:591–596. doi: 10.1172/JCI115034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fidge N, Nestel P, Ishikawa T, Reardon M, Billington T. Turnover of apoproteins A-I and A-II of high density lipoprotein and the relationship to other lipoproteins in normal and hyperlipidemic individuals. Metabolism. 1980;29:643–653. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(80)90109-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Clay MA, Newnham HH, Barter PJ. Hepatic lipase promotes a loss of apolipoprotein A-I from trigryceride-enriched human high density lipoproteins during incubation in vitro. Arteriosclerosis. 1991;11:415–422. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.11.2.415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Glass C, Pittman RC, Civen M, Steinberg D. Uptake of high density lipoprotein-associated apoprotein A-I and cholesterol esters by 16 tissues of the rat in vivo and by adrenal cells and hepatocytes in vitro. J Biol Chem. 1983;260:744–750. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Goldberg IJ, Blaner WS, Vanni TM, Moukides M, Ramakrishnan R. Role of lipoprotein lipase in the regulation of high density lipoprotein apolipoprotein metabolism: Studies in normal and lipoprotein lipase-inhibited monkeys. J Clin Invest. 1990;86:463–473. doi: 10.1172/JCI114732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Horowitz BS, Goldberg IJ, Merab J, Vanni T, Ramakrishnan R, Ginsberg HN. Increased plasma and renal clearance of an exchangeable pool of apolipoprotein A-I in subjects with low levels of high density lipoprotein cholesterol. J Clin Invest. doi: 10.1172/JCI116384. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tall AR, Granot E, Tabas I, Williams KJ, Brocia R, Hesler C, Denke M. Accelerated transfer of cholesteryl esters in dyslipidemic plasma: Role of cholesteryl ester transfer protein. J Clin Invest. 1987;79:1217–1225. doi: 10.1172/JCI112940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mann CJ, Yen FT, Grant AM, Bihan BE. Mechanisms of plasma cholesteryl ester transport in hypertriglyceridemia. J Clin Invest. 1991;88:2059–2066. doi: 10.1172/JCI115535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Austin MA, King MC, Vranizan KM, Krauss RM. Atherogenic lipoprotein phenotype: A proposed marker for coronary heart disease risk. Circulation. 1990;82:495–506. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.82.2.495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Austin MA, Brunzell JD, Fitch WL, Krauss RM. Inheritance of low density lipoprotein subclass patterns in familial combined hyperlipidemia. Arteriosclerosis. 1990;10:520–530. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.10.4.520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Melish J, Le NA, Ginsberg H, Steinberg D, Brown WV. Dissociation of triglyceride and apoprotein-B production in very low density lipoproteins. Am J Physiol. 1980;239:E354–E362. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1980.239.5.E354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schwartz CC, Zech LA, Vandenbroek JM, Cooper PS. Reverse cholesterol transport measured in vivo in man: The central roles of HDL. In: Miller NE, editor. High Density Lipoproteins and Atherosclerosis II. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 1989. pp. 321–329. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Glomset JA. The plasma lecithin: cholesterol acyltransferase reaction. J Lipid Res. 1968;9:155–167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tall AR. Plasma lipid transfer proteins. J Lipid Res. 1986;27:361–368. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Malloy LK, VandenBroek JM, Zech LA, Schwartz CC. HDL esterified cholesterol uptake by tissues is negligible in vivo in man. Arteriosclerosis. 1990;10:776a. (abstract) [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rinninger F, Pittman RC. Regulation of the selective uptake of high density lipoprotein-associated cholesteryl esters by human fibroblasts and Hep G2 hepatoma cells. J Lipid Res. 1988;29:1179–1194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]