Abstract

Umbilical cord stroma mesenchymal stem cells were differentiated toward chondrocyte-like cells using a new in vitro model that consists of the random formation of spheroids in a medium supplemented with fetal bovine serum on a nonadherent surface. The medium was changed after 2 days to one specific for the induction of chondrocyte differentiation. We assessed this model using reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction, flow cytometry, immunohistochemistry, and secretome analyses. The purpose of this study was to determine which proteins were differentially expressed during chondrogenesis. Differential gel electrophoresis analysis was performed, followed by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization mass spectrometry protein identification. A total of 97 spots were modulated during the chondrogenesis process, 54 of these spots were identified as 39 different proteins and 15 were isoforms. Of the 39 different proteins identified 15 were down-regulated, 21 were up-regulated, and 3 were up- and down-regulated during the chondrogenesis process. Using Pathway Studio 7.0 software, our results showed that the major cell functions modulated during chondrogenesis were cellular differentiation, proliferation, and migration. Five proteins involved in cartilage extracellular matrix metabolism found during the differential gel electrophoresis study were confirmed using Western blot. The results indicate that our in vitro chondrogenesis model is an efficient and rapid technique for obtaining cells similar to chondrocytes that express proteins characteristic of the cartilage extracellular matrix. These chondrocyte-like cells could prove useful for future cell therapy treatment of cartilage pathologies.

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs)1 are undifferentiated cells with unlimited self-renewal capacity found in most organs and tissues of adult organisms. MSCs have proven to be a versatile source of cells capable of differentiating into various cellular lineages (1). MSCs have been isolated from a number of organs or tissues including adipose tissue (2), muscle (3), and umbilical cord (UC) (4). Our group has conducted proteome studies of chondrocytes with diverse pathologies (5, 6) and has also achieved differentiation toward chondrocyte-like cells of MSCs from UC stroma using a new spheroid model and defined chondrogenic medium (7). Our findings demonstrate that MSCs from UC stroma are multipotent cells capable of differentiation into mesodermal and ectodermal cell lineages (7). Various techniques, including immunohistochemistry, reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), and one-dimensional SDS-PAGE (1D-SDS-PAGE) coupled to nano liquid chromatography matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization (nano LC MALDI) time-of-flight (TOF)/TOF yielded evidence of proteins and gene expressions characteristic of native cartilage by these cells (7). The goal of the study reported here was to quantify the proteome of MSCs of human UC stroma (UCs) using differential gel electrophoresis (DIGE) proteome analysis to identify key pathways involved in our chondrogenic process that may prove useful for cell therapy of cartilage pathologies.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Tissue Collection

Human UCs were obtained from caesarean sections performed on 23 healthy women at the Maternity Facility at Complejo Hospitalario Universitario A Coruña (CHUAC). All tissues were obtained with fully informed consent and ethical approval by the supervisor of the Ethical Committee (CEIC) of Galicia. All the women were between 26 and 35 years-old.

Isolation and Culture of MSCs

MSCs were isolated from UCs using the protocol developed by our group (4). Briefly, the tissue was washed with phosphate buffered saline and cut into small pieces (explants). These explants were then incubated for three five-minute periods in an enzyme mixture containing 1.2 U/ml dispase and 112 U/ml type I collagenase (all from Sigma-Aldrich) and cultured in Dulbecco′s Modified Eagles Medium with 10% fetal bovine serum, 1% penicillin, and 1% streptomycin (all from Sigma-Aldrich) and growth adhered to the plastic plate. After 3 days, the explants were removed from the plate, leaving the attached UC MSCs, which were then cultured in monolayer in the same medium. When the cells were 90% confluent, they were removed from the plate using 2% trypsin (Sigma-Aldrich) in phosphate-buffered saline and induced to differentiate toward chondrogenesis.

The MSCs were seeded into 96-well plates (Sarstedt, Inc., Barcelona, Spain) at 2 × 104 cells per well in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium with 10% fetal bovine serum, 1% penicillin, 1% streptomycin, 1.5 × 10−4 M of monothioglycerol, 5 mg/ml ascorbic acid, and 6 μg/ml transferrin (all from Sigma-Aldrich) to facilitate spontaneous spheroid formation. The medium was then changed to a chondrogenic medium, composed of Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium with 15% knockout serum (Invitrogen, Barcelona, Spain), 5 mg/ml ascorbic acid, 6 μg/ml transferrin, 10 μm dexamethasone, 1 × 10–7 M retinoic acid and 1 ng/ml recombinant human transforming growth factor-β3 (ProSpec-Tany TechnoGene, Deltaclon, Madrid, Spain). This medium was changed every 3 days. After 4, 7, 14, 28, and 46 days in the chondrogenic medium, spheroids were collected, frozen, and stored at 4 °C for later analyses.

DIGE Sample Preparation and Labeling

Spheroids recovered from the culture plates were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline. The spheroids were disaggregated using a Mixer Mill MM 200 (RESTCH, Haan, Germany) with zirconium balls in liquid nitrogen followed by a one-hour incubation with gentle agitation in 200 μl of isolectric focusing-compatible lysis buffer containing 8.4 m urea, 2.4 m thiourea, 5% 3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)dimethylammonio]propanesulfonate, 1% carrier ampholytes [imobilized pH gradient (IPG) buffer], 0.4% Triton X-100 and 2 mm dithiothreitol (Sigma-Aldrich) at pH 8 to 9. Total proteins in each lysate were quantified using the Bradford protein assay (Sigma-Aldrich). The samples were labeled using fluorescent Cy Dyes according to the manufacturer's instructions (GE Healthcare, Buckinghamshire, UK). Three chondrogenic differentiations were used for each sample at each collection time. The sample labeling is shown in Table I.

Table I. Samples used for the differential gel electrophoresis (DIGE) analysis. Mesenchymal stem cells from 12 donors were differentiated toward chondrocyte-like cells. The top of the table indicates the amount of protein used in DIGE experiments labeled with Cy2, Cy3, or Cy5 dye. The first column indicates the gel number; the following columns indicate the days in differentiation medium charged in the gel. Three different experiments were performed and are indicated as *, ′, and ″. Each experiment utilized a pool of three chondrogenic differentiations from three different donors. Standard is the mix of same amount of protein of each condition.

| Cy2 (50 μg) | Cy3 (50 μg) | Cy5 (50 μg) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| GEL1 | Standard | 0* | 4* |

| GEL2 | Standard | 7* | 14* |

| GEL3 | Standard | 28* | 46* |

| GEL4 | Standard | 4′ | 0′ |

| GEL5 | Standard | 14′ | 7′ |

| GEL6 | Standard | 46′ | 28′ |

| GEL7 | Standard | 0″ | 4″ |

| GEL8 | Standard | 7″ | 14″ |

| GEL9 | Standard | 28″ | 46′ |

2D-Gel Electrophoresis

IPG strips (pH 3–11, 24 cm, Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) were rehydrated with hydration buffer (8.4 m Urea, 2 m thiourea, 2% 3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)dimethylammonio]propanesulfonate, 0.02% bromphenol blue, 0.5% carrier ampholytes, 1.2% Destreak (GE Healthcare) for 18 h at room temperature. Cy Dye-labeled samples were loaded into a cap-load covered with Cover Fluid (GE Healthcare) and isoelectric focusing was performed for a total of 95,000 Vh for 24 cm strips using the IPGphor-II apparatus (GE Healthcare). The strips were equilibrated prior to SDS-PAGE for 15 min in equilibration buffer (6 m urea, 50 mm Tris pH 8.8, 20% (v/v) glycerol, 2% (w/v) SDS) with 1% (v/v) dithiotreitol, then for an additional 15 min in the same equilibration buffer with 4% (v/v) iodine acetamine. The strips were overlaid with 1% agarose in SDS running buffer containing bromphenol blue. Tris-glycine running buffer (24.8 mm Tris, 192 mm glycine, 0.1% (w/v) SDS) was used. The 24-cm gels were run on a Criterion gel system (Bio-Rad Laboratories) for the second dimension until the dye front passed the bottom of the gel. The gels were immediately scanned. A non-DIGE preparative gel was run with 500 μg protein from a pool of all samples under the same conditions. This gel was stained with Coomassie blue and spots were excised for protein identification.

Gel Imaging

The gels were scanned using a Typhoon9410 scanner (GE Healthcare) following the manufacturer's instructions. Image analysis was performed using the DeCyder software package version 5 (GE Healthcare), a 2-DE analysis software specifically designed for DIGE experiments. [1370 spots were identified and quantified using the DeCyder difference in-gel analysis (DIA) module. Proteins were deemed to be differentially expressed if they showed a greater than 1.5-fold change in abundance and if p < 0.05 was found using a 1-way ANOVA. Ninety-seven spots were observed to be modulated.

MS Analysis

The samples were first reduced using dithiotreitol, then alkylated with iodoacetamide and digested at 37 °C using 6.66 ng/μl sequencing-grade trypsin (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Indianapolis, IN). Following digestion, the supernatant was collected and a 1 μl spot placed on a MALDI target plate (ABSciex, Framingham, MA) and allowed to air-dry at room temperature. When dried, 0.5 μl of a 3 mg/ml solution of α-cyano-4-hydroxy-trans-cinnamic acid matrix in 0.1% trifluroacetic acid-50% acetonitrile was added to the dried peptide spots and allowed to air-dry. The samples were analyzed using the MALDI-TOF/TOF mass spectrometer 4800 Proteomics Analyzer (ABSciex, Framingham, MA) and 4000 Series Explorer™ Software (ABSciex). MALDI-TOF spectra were acquired in reflector positive-ion mode using 1000 laser shots per spectrum. Data Explorer version 4.2 (ABSciex) was used for spectra analyses and generating peak-picking lists. All mass spectra were internally calibrated using autoproteolytic trypsin fragments and externally calibrated using a standard peptide mixture 4700 CAL MIX (ABSciex). TOF/TOF fragmentation spectra were acquired by selecting the 20 most abundant ions of each MALDI-TOF peptide mass map, excluding trypsin autolytic peptides and other known background ions, using an average of 1500 laser shots per fragmentation spectrum. The parameters utilized for analysis were a signal to noise threshold of 20, a minimum area of 100 and a resolution higher than 10,000 with a mass accuracy of 20 ppm.

Database Search

The amino acid sequence tag obtained from each peptide fragmentation in MS/MS analyses were used to search for protein candidates using Mascot online 2.0 as search engine (www.matrixscience.com). Peak intensity was used to select up to 50 peaks per spot for peptide mass fingerprinting, and 50 peaks per precursor for MS/MS identification. Tryptic autolytic fragments, keratin, and matrix-derived peaks were removed from the data used for the search. The searches for peptide mass fingerprints and tandem MS spectra were performed in the Swiss-Prot release 53.0 database (269.293 entries) without taxonomy restriction. Fixed and variable modifications were considered (Cys as carbamidomethyl derivate and Met as oxidized methionine, respectively), allowing one trypsin-missed cleavage site and a mass tolerance of 50 ppm. For MS/MS identifications, a precursor tolerance of 50 ppm and MS/MS fragments tolerance of 0.3 Da were used. Identification was accepted as positive when at least two peptides matched and at least 10% of the peptide coverage of the theoretical sequences matched within a mass accuracy of 50 or 25 ppm with internal calibration. Probability scores were significant at p < 0.01 for all matches. Proteins of interest were excised from the preparative gel for protein identification. Preparation for protein identification used the protocol from Gez et al. (8).

Protein Isolation and Immunoblot Analysis

Immunoblot analysis was performed using 40 μg of total protein extracted from cells in culture, as previously described (9). The blots were probed with antibodies directed against human superoxide dismutase mitochondrial (SODm), protein disulfide-isomerase A1 (PDIA), 78 kDa glucose-regulated protein (GRP78), peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase A (PPIA), heat shock protein HSP90-beta (HSP90), procollagen-lysine (PLOD2) (all from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) and glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) (Sigma-Aldrich). A secondary anti-mouse antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) was used to visualize proteins using an Amersham BiosciencesTM ECLTM Western blotting analysis system (GE Healthcare, Amersham Biosciences Biotechnology, UK). Ideal concentrations for each antibody were determined empirically. Working concentrations were 1:1000 of the recommended stock solutions. Three experiments were performed. One of them was a pool from the DIGE/MS analysis and the other two were from other random experiments.

Real-time Reverse Transcriptase PCR (qRT-PCR) Analysis

The reported sequences of genes for human SODm (forward: CTGGACAAACCTCAGCCCTA; reverse: TGATGGCTTCCAGCAACTC), PDIA (forward: TTGGCCTCACCAAGGACA; reverse: TGACCAGGAAGCGCGACA), GRP78 (forward: GGATCATCAACGAGCCTACG; reverse: CACCCAGGTCAAACACCAG), PPIA (forward: ATGCTGGACCCAACACAAAT; reverse: TCTTTCACTTTGCCAAACACC), HSP90 (forward: CGTTGCTCACTATTACGTATAATCCT; reverse: TGCCTGAAAGGCAAAAGTCT), PLOD2 (forward: TCATGGACACAGGATAATGGCTGCA; reverse: AGGTAGAAAAGGGGTTGGTTGCTCA), and 50S ribosomal protein L16 (RPLP) (forward: TCTACAACCCTGAAGTGCTTGAT; reverse: CAATCTGCAGACAGACACTGG) as housekeeping were used for primer design. The amplification program consisted of an initial denaturation at 92 °C for 2 min followed by 40 cycles from 92 °C for 15 s, annealing at 61 °C for 30 s, and an extension at 72 °C for 15 s. Each PCR analysis was performed in duplicate, with each set of assays repeated three times. To minimize effects of unequal quantities of starting RNA and to eliminate potential sources of inconsistency, relative expression levels of each gene were normalized to RPLP using the 2-ΔΔCt method (10). Control experiments contained no reverse transcriptase.

RESULTS

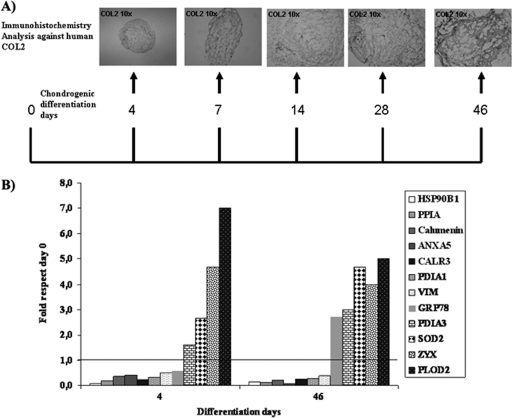

All proteins from chondrocyte-like cells were compared with proteins secreted by undifferentiated cells at time point 0. Twelve differentiations of MSCs from human UC stroma donors were achieved. Representative images of the chondrogenic process identified using immunohistochemistry against human collagen type II (COL2) for each collection time are shown in Fig. 1A.

Fig. 1.

Chondrogenesis model. A, Experimental plan indicating which days of chondrogenesis were used for differential-in-gel electrophoresis (DIGE) analyses. Representative immunohistochemical images of the expression of collagen type II (COL2) from spheroids engineered from umbilical stroma mesenchymal stem cells collected at different time points before DIGE analysis are shown at the top (Magnification 10×). B, Graph showing modulated proteins (previously identified as directly associated with the native cartilage extracellular matrix or chondrocytes) identified by mass spectroscopy during the chondrogenesis process at 4 and 46 days and their expression relative to that found in undifferentiated cells at time 0. They were listed in order from lowest to highest.

Three pools from three differentiation experiments were combined to perform three different DIGE analyses (Table I). 1370 spots were detected, 97 of which were significant at p < 0.01 (one way ANOVA). From the 97 spots, 54 proteins were identified by MS/MS (Table II). All modulated 54 proteins expressed during the chondrogenesis process were up- or down-regulated as early as 4 days of culture in chondrogenic medium. From a total of 97 proteins modulated during chondrogenesis differentiation, 15 were down-regulated, 21 were up-regulated, and three were down-regulated at the beginning of chondrogenesis and up-regulated at the final of process (Table III). Interestingly, from all modulated proteins 12 have been identified in the literature as characteristic proteins of the chondrogenesis process or as directly associated with the native cartilage extracellular matrix (ECM) or chondrocytes (Table III). PDIA3, SOD2, ZYX, and PLOD2 were clearly up-regulated during chondrogenesis at 4 and 46 days (Fig. 1B).

Table II. Proteomic analysis at different times of chondrogenesis from mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) from human umbilical cord stroma using a two-dimensional DIGE technique coupled to MALDI-TOF/TOF. Only those proteins modulated during chondrogenesis identified by at least two specific human peptides with confidence >99% are included in the list.

| NAME | MSMS match | Location | Score | # ID peptides | Spot | p anova |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Annexin A2 | ANXA2_HUMAN | Extracellular matrix | 973 | 15 | 775 | 2.58E-01 |

| Peroxiredoxin-5 | PRDX5_HUMAN | Mitochondrion | 475 | 7 | 565 | 6.73E-01 |

| GRP78 | GRP78 | Endoplasmic reticulum | 772 | 17 | 656 | 0.001 |

| Protein disulfide-isomerase A3 | PDIA3_HUMAN | Endoplasmic reticulum | 872 | 13 | 675 | 0.001 |

| Tropomyosin beta chain | TPM2_HUMAN | Cytoplasm | 190 | 4 | 759 | 0.002 |

| Transgelin | TAGL_HUMAN | Cytoplasm | 673 | 15 | 637 | 0.002 |

| Heat shock protein, mitochondrial | CH60_HUMAN | Mitochondrion | 75 | 3 | 1091 | 0.002 |

| Vimentin | VIME_HUMAN | Intermediate filament | 252 | 9 | 751 | 0.002 |

| Protein DJ-1 | PARK7_HUMAN | Nucleus | 270 | 9 | 833 | 0.003 |

| Protein SET | SET_HUMAN | Endoplasmic reticulum | 66 | 2 | 693 | 0.003 |

| Calreticulin | CALR_HUMAN | Endoplasmic reticulum | 551 | 8 | 578 | 0.003 |

| Reticulocalbin-3 | RCN3_HUMAN | Endoplasmic reticulum | 423 | 7 | 655 | 0.004 |

| Annexin A5 | ANXA5_HUMAN | Extracellular matrix | 644 | 12 | 788 | 0.004 |

| Annexin A1 | ANXA1_HUMAN | Extracellular matrix | 1329 | 15 | 776 | 0.004 |

| Transgelin | TAGL_HUMAN | 371 | 15 | 1089 | 0.005 | |

| Annexin A1 | ANXA1_HUMAN | Extracellular matrix | 1029 | 15 | 772 | 0.005 |

| Heat shock protein beta-1 | HSPB1_HUMAN | Cytoplasm | 585 | 8 | 849 | 0.005 |

| Endoplasmin | ENPL_HUMAN | Endoplasmic reticulum | 542 | 12 | 526 | 0.005 |

| Annexin A6 | ANXA6_HUMAN | Extracellular matrix | 708 | 3 | 391 | 0.005 |

| Procollagen-lysine | PLOD2_HUMAN | Endoplasmic reticulum membrane | 184 | 3 | 221 | 0.008 |

| Reticulocalbin-1 | RCN1_HUMAN | Endoplasmic reticulum | 187 | 4 | 695 | 0.008 |

| Stress-induced-phosphoprotein 1 | STIP1_HUMAN | Cytoplasm & nucleus | 122 | 5 | 671 | 0.008 |

| Peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase A | PPIA_HUMAN | Cytoplasm | 550 | 8 | 1250 | 0.009 |

| Annexin A1 | ANXA1_HUMAN | Extracellular matrix | 874 | 15 | 632 | 0.009 |

| Peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase A | PPIA_HUMAN | Cytoplasm | 508 | 8 | 1285 | 0.011 |

| Annexin A5 | ANXA5_HUMAN | Extracellular matrix | 691 | 12 | 1081 | 0.011 |

| Zyxin | ZYX_HUMAN | Cytoplasm & nucleus | 206 | 6 | 186 | 0.011 |

| Annexin A2 | ANXA2_HUMAN | Extracellular matrix | 396 | 13 | 783 | 0.013 |

| Superoxide dismutase | SODM_HUMAN | Mitochondrion | 391 | 5 | 864 | 0.014 |

| Phosphoglycerate mutase 1 | PGAM1_HUMAN | Cytoplasm | 381 | 8 | 843 | 0.015 |

| Ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolase isozyme L1 | UCHL1_HUMAN | Cytoplasm | 223 | 8 | 896 | 0.017 |

| Ferritin light chain | FRIL_HUMAN | Cytoplasm | 130 | 4 | 1305 | 0.017 |

| Nucleoside diphosphate kinase A | NDKA_HUMAN | Cytoplasm & Nucleus | 269 | 6 | 1278 | 0.018 |

| Annexin A2 | ANXA2_HUMAN | Extracellular matrix | 492 | 13 | 781 | 0.019 |

| Superoxide dismutase | SODM_HUMAN | Mitochondrion | 130 | 5 | 1082 | 0.020 |

| Protein disulfide-isomerase A3 | PDIA3_HUMAN | Endoplasmic reticulum | 457 | 13 | 672 | 0.031 |

| Tyrosyl-tRNA synthetase, cytoplasmic | SYYC_HUMAN | Cytoplasm | 64 | 2 | 469 | 0.033 |

| Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase | G3P_HUMAN | Membrane | 62 | 3 | 509 | 0.033 |

| Transgelin-2 | TAGL2_HUMAN | Membrane | 809 | 14 | 1075 | 0.033 |

| Heat shock protein beta-1 | HSPB1_HUMAN | Cytoplasm & Nucleus | 405 | 8 | 978 | 0.034 |

| Nicotinamide N-methyltransferase | NNMT_HUMAN | Cytoplasm | 486 | 10 | 873 | 0.034 |

| Calumenin | CALU_HUMAN | Endoplasmic reticulum | 448 | 7 | 680 | 0.035 |

| Peroxiredoxin-6 | PRDX6_HUMAN | 381 | 7 | 848 | 0.039 | |

| Annexin A5 | ANXA5_HUMAN | Extracellular matrix | 277 | 12 | 634 | 0.039 |

| Triosephosphate isomerase | TPIS_HUMAN | Cytoplasm | 1061 | 14 | 858 | 0.039 |

| Alpha-enolase | ENOA_HUMAN | 631 | 9 | 650 | 0.040 | |

| Annexin A2 | ANXA2_HUMAN | Extracellular matrix | 643 | 13 | 774 | 0.043 |

| Glutathione S-transferase P | GSTP1_HUMAN | Cytoplasm | 439 | 6 | 951 | 0.045 |

| Caldesmon | CALD1_HUMAN | Plasma membrane | 280 | 8 | 283 | 0.046 |

| Vimentin | VIME_HUMAN | Intermediate filament | 193 | 9 | 673 | 0.046 |

| Protein disulfide-isomerase A1 | PDIA1_HUMAN | Endoplasmic reticulum | 1045 | 13 | 616 | 0.046 |

| Protein disulfide-isomerase A3 | PDIA3_HUMAN | Endoplasmic reticulum | 543 | 13 | 615 | 0.048 |

| Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein d-like | HNRDL_HUMAN | Cytoplasm & Nucleus | 204 | 4 | 770 | 0.048 |

| Caldesmon | CALD1_HUMAN | Plasma membrane | 267 | 8 | 275 | 0.050 |

Table III. Modulated proteins identified by MALDI-TOF/TOF during chondrogenesis using our spheroid model. The first column on the left lists the name of the protein and the top line shows the days of differentiation. The numbers indicate the score. The controls (undifferentiated cells at time 0) were assigned the number 1; therefore proteins with scores <1 were down-regulated and those with scores >1 were up-regulated. The shaded, colored boxes indicate proteins found in cartilage or chondrocytes with the literature source citation.

| Name/diff day | 4 | 7 | 14 | 28 | 46 | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HSP90B1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 | (Ruiz-Romero C. et al. 2010) |

| PPIA | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | (Satoh et al. 2009)[1] |

| Calumenin | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.2 | (Coppinger et al. 2004)[2] |

| FTL | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.1 | |

| ANXA5 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | (Ulbrich et al. 2010)[3] |

| SET | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.3 | |

| NME1 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.2 | |

| CALR3 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.3 | (Van Duyn Graham et al. 2010)[4] |

| RCN3 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.1 | |

| RCN1 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.2 | |

| PRDX5 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.2 | |

| PDIA1 | 0.3 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | (Ruiz-Romero C. et al. 2010) |

| VIM | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.4 | (Bobick et al. 2010)[5] |

| GSTP1 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 0.5 | |

| PGAM1 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 2.5 | |

| GRP78 | 0.6 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 2.4 | 2.7 | (Calamia V. et al. 2010) |

| PRDX6 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 1.0 | 2.4 | |

| TPI1 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 1.0 | 0.8 | 2.2 | |

| HSPA5 | 0.7 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 2.7 | 3.0 | |

| HSPB1 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.5 | 2.0 | |

| ENO1 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.9 | |

| PHGDH | 1.6 | 1.4 | 1.1 | 1.4 | 1.9 | |

| STIP1 | 1.4 | 1.6 | 1.2 | 1.6 | 3.2 | |

| PDIA3 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.4 | 1.8 | 3.0 | (Boyan and Schwartz 2009) |

| NNMT | 2.0 | 2.3 | 1.5 | 2.0 | 3.3 | |

| HNRPDL | 2.8 | 2.3 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 2.8 | |

| ANXA2 | 1.7 | 2.0 | 1.7 | 2.0 | 5.3 | |

| UCHL1 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 4.0 | |

| SODm | 2.7 | 2.3 | 2.0 | 3.0 | 4.7 | (Kim et al. 2010)[6] |

| YARS | 1.3 | 1.8 | 2.0 | 2.2 | 1.7 | |

| ADAM15 | 3.0 | 3.2 | 2.2 | 1.8 | 1.8 | |

| ANXA1 | 2.3 | 2.0 | 2.3 | 2.0 | 3.5 | |

| HSPD1 | 1.7 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 3.0 | 4.7 | |

| TAGLN2 | 1.7 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 4.3 | |

| ANXA6 | 4.2 | 4.4 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.8 | |

| CALD1 | 3.5 | 2.3 | 3.8 | 6.6 | 3.2 | |

| TAGLN | 3.0 | 3.5 | 4.5 | 5.0 | 6.5 | |

| ZYX | 4.7 | 4.0 | 4.7 | 3.7 | 4.0 | (Hirsch et al. 1996, Petroll and Ma 2003)[7] |

| PLOD2 | 7.0 | 5.5 | 5.0 | 3.5 | 5.0 | (van den Bogaerdt et al. 2009)[8] |

[1] Not in ref list.

[2] Not in ref list.

[3] Not in ref list.

[4] Not in ref list.

[5] Not in ref list.

[6] Not in ref list.

[7] Not in ref list.

[8] Not in ref list.

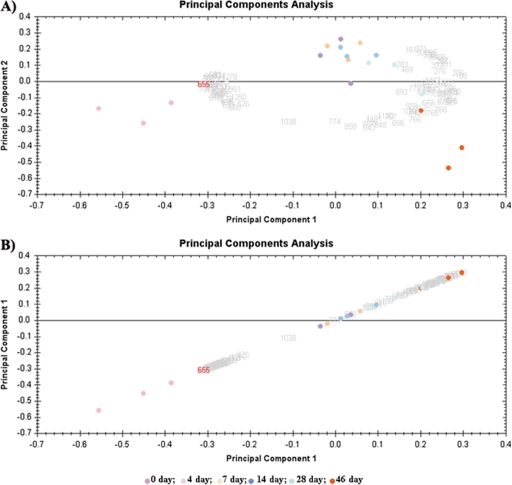

Principal component analysis was used to determine whether the proteomic profile obtained from our chondrogenesis model was homogenous. Proteomic maps were utilized for variables and spots from the different groups were used as observations in “score graphs.” Score graphs are useful for reducing complexity and obtaining a simplified examination of proteomic spots. Score graphs can be used to determine whether the samples express a similar proteomic profile and whether the spots belong to the same experimental group. Fig. 2A shows that day 0 spots (pink) were much closer to each other and situated at one side of the graph, whereas day 46 spots (green) were clustered at the opposite side. Spots corresponding to the intermediate differentiation days are situated between these positions. Plotting these data using the same variable on both axes to make the data linear did not change the proteomic profile (Fig. 2B). These results indicated that our data were very homogeneous with no discordant data affecting the statistical analysis.

Fig. 2.

Principal components analysis of differential-in-gel electrophoresis (DIGE) data. Scores graphs combining proteomic maps (variables) and spots from different groups (observations) were constructed. A, Principal components analysis clustered the nine individual Cy3- and Cy5-labeled expression maps into six different groups. Principal component 1 was 66.75% from the modulated proteins and principal component 2 was 14.32% from the modulated proteins. B, Principal component 1 was 66.75%.

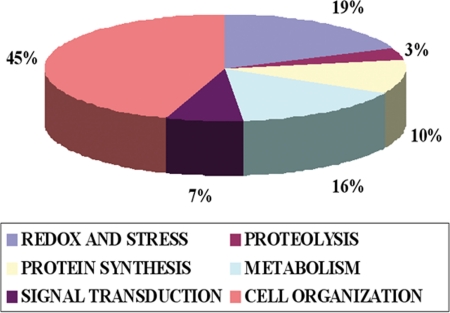

The major proteins found in our chondrogenesis model after day 4 of differentiation were grouped according to three primary cell functions. In cellular proliferation were annexins 1 (ANXA1) and 6 (ANXA6), heat shock 70 kDa protein 14 (HSP70), caldesmon (CALD1), transgeline (TAGL), and zyxin (ZYX), all up-regulated. Proteins involved in cell differentiation were peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase A (PPIA), heat shock 90 kDa protein (HSP90) and glutathione S-transferase P (GSTP1), all down-regulated. Proteins involved in cell migration were protein disulfide-isomerase A1 (PDIA1) and nucleoside diphosphate kinase A (NME1), which were down-regulated. The modulated proteins grouped according to cell function were examined and we found that those involved in cell organization were 45% of the total modulated proteins, followed by of 19% involved in reduction-oxidation stress, 16% in metabolism and 7% in signal transduction (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Cellular functions during chondrogenesis. The graph represents the percentage of modulated proteins found in our chondrogenesis model involved in the main cellular functions.

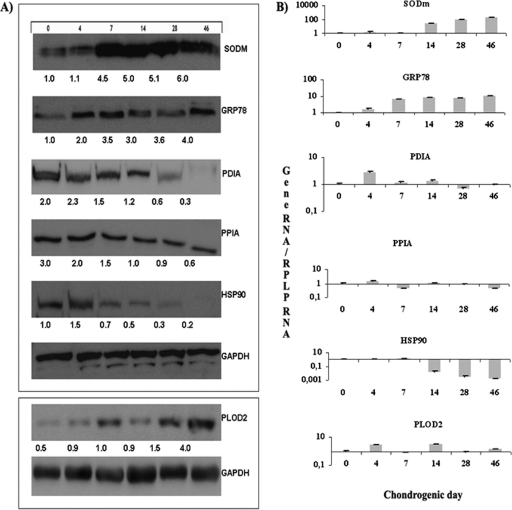

The expression of six representative proteins was determined throughout chondrogenesis in our model using immunoblot analysis to validate the results from the DIGE technique. SODm, GRP78, and PLOD2 increased their expression at 4 days and continued to increase throughout the differentiation process. PDIA1, PPIA, and HSP90 were decreased at 4 days and continued decreasing throughout (Fig. 4A). These results confirm the results obtained from the DIGE analyses. Gene expressions for each protein was analyzed by qRT-PCR during chondrogenic process and they were coincident with their protein levels for the different times of chondrogenic differentiation found by DIGE and validated by immunoblotting (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

Validation of six representative proteins found to be modulated during chondrogenesis. A, Western blot at 0, 4, 7, 14, 28, and 46 days in chondrogenic medium of each protein. The density value of each band was normalized to the GAPDH level and expressed relative to the control, shown as fold-induction written under each band. B, Histogram represents gene expression of each protein by Real-time reverse transcriptase PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis normalized by expression of RPLP gene, which was taken as housekeeping. Superoxide dismutase mitochondrial = SODm; Protein disulfide-isomerase A1, PDIA; 78kDa glucose-regulated protein, GRP78; Peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase A, PPIA; Heat shock protein HSP90-beta, HSP90; Procollagen-lysine, PLOD2; Glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, GAPDH. The sample used for the representative western shown was a pool from the DIGE/MS analysis. Three replicates were made.

DISCUSSION

Over the past year, our group has reported proteomic studies of chondrocytes in various pathologies and under differing culture conditions (11). This is the first report of a study of chondrogenic differentiation of MSCs from a novel source, the UC stroma. DIGE has previously been used to analyze osteoblast differentiation from MSCs of adipose tissue (12) and to study nuclear proteomes from human embryonic and MSCs (13). However, to our knowledge, our study is the first one using DIGE to study the proteome of UC MSCs undergoing chondrogenic differentiation at six different time points (0, 4, 7, 14, 28, and 46 days) (Fig. 1). This approach represents a new global comparative proteomics approach with broad applications for basic and clinical biological sciences. Our primary goal was to identify pathways involved in chondrogenesis to validate and improve our in vitro chondrogenic model (4) with our ultimate objective being to develop new therapies for cartilage degeneration pathologies.

The principal components analysis results indicated that our data were very homogeneous with no discordant data affecting the statistical analysis (Fig. 2). The modulated proteins were either up- or down-regulated in the directed medium at all the time points from 4 days to 46 days, with significant differences found mainly between undifferentiated time 0 MSCs and the chondrocyte-like cells after 4 days of differentiation (Table III). Recent studies have shown that MSCs are capable of differentiation toward chondrocyte-like cells as soon as 3 days under appropriate culture conditions (14) and are able to maintain this differentiated stage for a long time in these culture conditions. That the modulated proteins in our study retain either the up or down-regulation throughout the chondrogenic process indicates the consistency of our model and corroborates the results obtained in the principal components analysis. Proteins involving cell organization processes were the most abundant when we grouped the modulated proteins by function at 45% of the total modulated protein (Fig. 3), followed by proteins involved in stress-related mechanisms at 19%. These results are consistent with cellular changes shown experimentally in MSCs during the differentiation process.

The goal of this study was identify novel proteomic changes during chondrocyte development using a human cell model for chondrogenesis validated previously by our group (7). Results demonstrate that mesenchymal stem cells cultured in the chondrogenic medium become chondrocyte-like, as cells express protein observed in differentiated chondrocytes or in cartilage (Table II). Six proteins from all proteins modulate during chondrogenesis were validated by qRT-PCR and Western blot analysis. These proteins were SODm, PDIA, GRP78, PPIA, HSP90, and PLOD2, all of which have been previously identified in human chondrocytes (15). The Western blot and real-time reverse transcriptase PCR (qRT-PCR) results validate the results obtained by DIGE analysis (Fig. 4). The results for each protein were maintained independent of donor or analysis used.

Modulated proteins found to be up-regulated were procollagen-lysine (PLOD2), which stabilizes the synthesis of collagen type I and II and is involved in the chondrocytic response to TNF-α-mediated stimuli affecting cartilage homeostasis (16), enolase (ENO1), which increases hypoxia tolerance and is involved in glycolysis (17), Heat shock protein beta-1 (HSPB1), which increases cell survival in changing environments (18), superoxide dismutase (SODm), which destroys free radicals (a reduction in SODm is associated with the earliest stages of osteoarthritis in an animal model) (19), and zyxin (ZYX), which is involved in signaling pathways. Recent research elaborated by our group revealed that overexpression of Lamin A leads to defects in differentiation potential of MSCs. The chondrogenic potential is defective in Lamin A-MSCs, and this lineage has an increase in hypertrophy markers during chondrogenic differentiation, as well as a decrease in manganese superoxide dismutase and an increase of mitochondrial manganese superoxide dismutase-dependent reactive oxygen species. Interestingly, defects in chondrogenesis are partially reversed by periodic incubation with a SODM-mimic agent, supporting the idea that the effect of Lamin A on chondrogenesis could be because it increases reactive oxygen species levels (20).

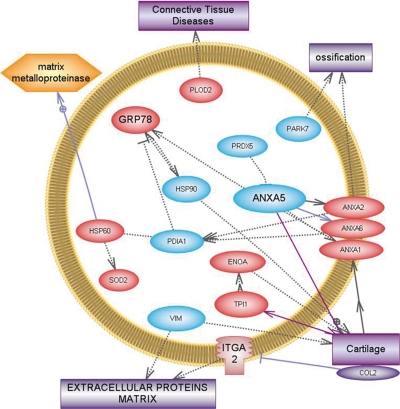

The proteins we found to be down-regulated were calreticulin, which is involved in processing and transport of wild type cartilage oligomeric matrix protein in normal chondrocytes and in the retention of mutant cartilage oligomeric matrix protein in pseudoachondroplasic chondrocytes (21), PDIA, which in low quantities increases protein aggregation and is involved in ECM formation (22), and vimentin, which is abundantly expressed in MSCs. The disruption of vimentin reduces stiffness ∼2.8-fold in normal chondrocytes, but osteoarthritic chondrocytes are less stiff and less affected by vimentin disruption (23). This three-dimensional experimental system revealed contributions of vimentin to chondrocyte stiffness not previously apparent, and correlated changes in vimentin-based chondrocyte stiffness with osteoarthritis (23). Some of the modulated proteins found by our DIGE analysis were involved in ossification, such as PARK7, which was down-regulated indicating that our model did not produce cellular hypertrophy (24). The up-regulation of ANXA2, ANX6, and ANXA1, and the down-regulation of ANXA5 indicate that chondrogenesis prevailed over osteogenesis (25) (Fig. 5). These results are logical in consideration that in our chondrogenic model undifferentiated MSCs at the beginning required proliferation before the process to change them into chondrocyte-like cells as a second step.

Fig. 5.

Relationships among proteins modulated during chondrogenesis. Graphic generated by Pathway Study 2 for PC software showing linked bibliographic information among the proteins found in our model directly involved in the native cartilage extracellular matrix, or chondrocytes. Proteins found to be up-regulated in our model are in red and those down-regulated are in blue. Functions and structures are in the rectangles and the yellow color indicates catabolism.

Our study of the role of zyxin and its mechanism to maintain mechanical homeostasis during the differentiation process from MSCs to chondrocyte-like cells is of particular interest. It is known that cells recognize and respond to changes in cytoskeletal integrity and zyxin could be performing this function. A recent study showed that actin stress fibers undergo local, acute, force-induced elongation and thinning events that compromise their stress transmission function, followed by stress fiber repair that restores this capability (26). Zyxin promoted recruitment of the actin regulatory proteins, α-actinin and Vasopresine, in compromised stress fiber zones (26), their findings demonstrate a mechanism for rapid repair and maintenance of the structural integrity of the actin cytoskeleton.

We conclude that MSCs differentiating toward chondrocyte-like cells express proteins characteristic of the native cartilage ECM. We have demonstrated that our in vitro chondrogenic model could be used for a variety of cell-based transplantation and tissue engineering studies. All these experiments are very relevant in the rheumatic disease field because a good in vitro model is necessary to study this pathology, which it is not accessible at present.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Purificación Filgueira and Ma José Sánchez for technical support and Nelson Alexandre da Cruz Soares for helpful suggestions.

Footnotes

* This study was supported by grants from Fundación Española de Reumatologia (programa GEN-SER) and from Fondo Investigación Sanitaria (CIBER-CB06/01/0040)-Spain, Fondo Investigacion Sanitaria-PI 08/2028 Ministerio Ciencia en Innovacion PLE2009–0144, with participation of funds from FEDER (European Community). Arufe is the beneficiary of an Isidro Parga Pondal contract from Xunta de Galicia, A Coruna, Spain. Alexandre de la Fuente is the beneficiary of a contract from Xunta de Galicia (2008), Spain.

1 The abbreviations used are:

- MSC

- mesenchymal stem cells

- UC

- umbilical cord

- DIGE

- differential gel electrophoresis

- MALDI-TOF

- matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization/time of flight

- SODm

- superoxide dismutase mitochondrial

- PDIA

- protein disulfide isomerase A1

- GRP78

- 78kDa glucose-regulated protein

- PPIA

- Peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase A

- HSP90

- heat shock protein 90.

REFERENCES

- 1. Duca M., Dozza B., Lucarelli E., Santi S., Di Giorgio A., Barbarella G. (2010) Fluorescent labeling of human mesenchymal stem cells by thiophene fluorophores conjugated to a lipophilic carrier. Chem. Commun. 46, 7948–7950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pachón-Peña G., Yu G., Tucker A., Wu X., Vendrell J., Bunnell B., Gimble J. (2010) Stromal stem cells from adipose tissue and bone marrow of age matched female donors display distinct immunophenotypic profiles. J. Cell. Physiol. 246, 843–851 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Torsney E., Xu Q. (2011) Resident vascular progenitor cells. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2, 304–311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nishiyama N., Miyoshi S., Hida N., Uyama T., Okamoto K., Ikegami Y., Miyado K., Segawa K., Terai M., Sakamoto M., Ogawa S., Umezawa A., The significant cardiomyogenic potential of human umbilical cord blood-derived mesenchymal stem cells in vitro. Stem Cells 2007; 25: 2017–2024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ruiz-Romero C., Calamia V., Rocha B., Mateos J., Fernández-Puente P., Blanco F. J. (2010) Hypoxia conditions differentially modulate human normal and osteoarthritic chondrocyte proteomes. J. Proteome Res. 9, 3035–3045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cillero-Pastor B., Ruiz-Romero C., Caramés B., López-Armada M. J., Blanco F. J. (2010) Proteomic analysis by two-dimensional electrophoresis to identify the normal human chondrocyte proteome stimulated by tumor necrosis factor alpha and interleukin-1beta. Arthritis Rheum. 62, 802–814 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Arufe M. C., De la Fuente A., Mateos J., Fuentes I., De Toro F. J., Blanco F. J. (2010) Analysis of the Chondrogenic Potential and Secretome of Mesenchymal Stem Cells Derived from Human Umbilical Cord Stroma. Stem Cells Dev. 2011. July; 20(7): 1199–1212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gez S., Crossett B., Christopherson R. I. (2007) Differentially expressed cytosolic proteins in human leukemia and lymphoma cell lines correlate with lineages and functions. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1774, 1173–1183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Matsushime H., Quelle D. E., Shurtleff S. A., Shibuya M., Sherr C. J., Kato J. Y. (1994) D-type cyclin-dependent kinase activity in mammalian cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 14, 2066–2076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Livak K. J., Schmittgen T. D. (2001) Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods 25, 402–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Calamia V., Ruiz-Romero C., Rocha B., Fernández-Puente P., Mateos J., Montell E., Vergés J., Blanco F. J. (2010) Pharmacoproteomic study of the effects of chondroitin and glucosamine sulfate on human articular chondrocytes. Arthritis Res. Ther. 12, R138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Giusta M. S., Andrade H., Santos A. V., Castanheira P., Lamana L., Pimenta A. M., Goes A. M. (2010) Proteomic analysis of human mesenchymal stromal cells derived from adipose tissue undergoing osteoblast differentiation. Cytotherapy 12, 478–490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jaishankar A., Barthelery M., Freeman W. M., Salli U., Ritty T. M., Vrana K. E. (2009) Human embryonic and mesenchymal stem cells express different nuclear proteomes. Stem Cells Dev. 18, 793–802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rothenberg A. R., Ouyang L., Elisseeff J. H. (2010) Mesenchymal stem cell stimulation of tissue growth depends on differentiation state. Stem Cells Dev. 2011. March; 20(3): 405–414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lires-Deán M., Caramés B., Cillero-Pastor B., Galdo F., López-Armada M. J., Blanco F. J. (2008) Anti-apoptotic effect of transforming growth factor-beta1 on human articular chondrocytes: role of protein phosphatase 2A. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 16, 1370–1378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ah-Kim H., Zhang X., Islam S., Sofi J. I., Glickberg Y., Malemud C. J., Moskowitz R. W., Haqqi T. M. (2000) Tumour necrosis factor alpha enhances the expression of hydroxyl lyase, cytoplasmic antiproteinase-2 and a dual specificity kinase TTK in human chondrocyte-like cells. Cytokine 12, 142–150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ruiz-Romero C., Carreira V., Rego I., Remeseiro S., López-Armada M. J., Blanco F. J. (2008) Proteomic analysis of human osteoarthritic chondrocytes reveals protein changes in stress and glycolysis. Proteomics 8, 495–507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lambrecht S., Dhaenens M., Almqvist F., Verdonk P., Verbruggen G., Deforce D., Elewaut D. (2010) Proteome characterization of human articular chondrocytes leads to novel insights in the function of small heat-shock proteins in chondrocyte homeostasis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 18, 440–446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Scott J. L., Gabrielides C., Davidson R. K., Swingler T. E., Clark I. M., Wallis G. A., Boot-Handford R. P., Kirkwood T. B., Talyor R. W., Young D. A. (2010) Superoxide dismutase downregulation in osteoarthritis progression and end-stage disease. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 69, 1502–1510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mateos J, De la Fuente A, Lesende-Rodriguez L, Arufe MC, Blanco FJ. Lamin A deregularion in human mesenchymal stem cells promotes an impairment in their chondrogenic potential and imbalance in their response to oxidative stress. Arthritis Rheumatism, 2011. (in revision) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hecht J. T., Hayes E., Snuggs M., Decker G., Montufar-Solis D., Doege K., Mwalle F., Poole R., Stevens J., Duke P. J. (2001) Calreticulin, PDI, Grp94 and BiP chaperone proteins are associated with retained COMP in pseudoachondroplasia chondrocytes. Matrix Biol. 20, 251–262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Boyan B. D., Schwartz Z. (2009) 1,25-Dihydroxy vitamin D3 is an autocrine regulator of extracellular matrix turnover and growth factor release via ERp60-activated matrix vesicle matrix metalloproteinases. Cells Tissues Organs. 189, 70–74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Haudenschild D. R., Chen J., Pang N., Steklov N., Grogan S. P., Lotz M. K., D'Lima D. D. (2011) Vimentin contributes to changes in chondrocyte stiffness in osteoarthritis. J. Orthop. Res. 29, 20–25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Shim S., Kwon Y. B., Yoshikawa Y., Kwon J. (2008) Ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolase L1 deficiency decreases bone mineralization. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 70, 649–651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wang W., Xu J., Kirsch T. (2005) Annexin V and terminal differentiation of growth plate chondrocytes. Exp. Cell Res. 305, 156–165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Smith M. A., Blankman E., Gardel M. L., Luettjohann L., Waterman C. M., Beckerle M. C. (2010) A zyxin-mediated mechanism for actin stress fiber maintenance and repair. Dev. Cell 19, 365–376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]