Abstract

Differential expression of ligands in the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum enables it to recognize different receptors on the erythrocyte surface, thereby providing alternative invasion pathways. Switching of invasion from using sialated to nonsialated erythrocyte receptors has been linked to the transcriptional activation of a single parasite ligand. We have used quantitative proteomics to show that in addition to this single known change, there are a significant number of changes in the expression of merozoite proteins that are regulated independent of transcription during invasion pathway switching. These results demonstrate a so far unrecognized mechanism by which the malaria parasite is able to adapt to variations in the host cell environment by post-transcriptional regulation.

Plasmodium falciparum is the most virulent species causing malaria in humans that affects and kills millions of people worldwide. The clinical symptoms of this parasitic disease are caused by the intraerythrocytic stages of the P. falciparum life cycle. Within the erythrocyte, the parasite matures over 48 h from ring stage to schizont stage. Upon maturation, the schizont ruptures and releases numerous invasive merozoites. Erythrocyte invasion is mediated by a range of different receptor-ligand interactions, with different parasite strains utilizing different receptor-ligand combinations. Two merozoite protein families termed reticulocyte-binding protein homologues (RH)1 and erythrocyte-binding ligands have been linked to the ability of the parasite to recognize different erythrocyte receptors, thereby providing alternative invasion pathways (reviewed in Refs. 1 and 2).

The P. falciparum W2mef clone can switch from a sialic acid-dependent to a sialic acid-independent invasion pathway (3, 4), and this switch is linked to the up-regulation of transcription and expression of PfRH4, as well as the post-transcriptional repression of expression of PfRH1, both members of the RH family (5–7). To date, these studies have focused on genome-wide transcriptional data with the subsequent expression analysis of a few selected candidate proteins that showed changes in transcription levels. Such an approach is unable to identify proteins regulated post-transcriptionally, and therefore a detailed analysis to correlate transcription, as well as protein expression, is essential.

Here, we have combined quantitative proteomics with transcriptional profiling to define the extent of post-transcriptional regulation during invasion pathway switching in P. falciparum. This approach identified a number of merozoite proteins whose expression levels are post-transcriptionally regulated during invasion pathway switching. Sialic acid removal from erythrocytes by neuraminidase (sialidase) has been widely used as a tool to investigate invasion pathway properties of various P. falciparum strains (3, 8–10). From this present work, it is clear that post-transcriptional regulation of protein expression plays an important role in invasion pathway switching; moreover, it also demonstrates that the parasite invasion machinery undergoes much larger changes than previously thought when it adapts to changes in the availability of erythrocyte receptors.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Parasite Cultivation, Isolation, and Adaptation to NM-treated Erythrocytes

P. falciparum W2mef clone was obtained from the MR4 Malaria Resource Centre. Cultivation of Plasmodium clones followed standard procedures (11).

For obtaining switched W2mefNM parasites, erythrocytes were treated with neuraminidase (Calbiochem) according to the method described in Ref. 13. Tightly synchronized late schizonts, ∼45 h post-invasion were separated and mixed with 10 milliunits/ml neuraminidase-treated erythrocytes to yield a 1% starting parasitemia. The culture was maintained at 2% hematocrit in RPMI 1640 with 2.5% Albumax in a 25-cm2 flask (Nunc). The culture was incubated at 37 °C. 50 μl of fresh, NM-treated erythrocytes were added to the culture twice a week. The medium was changed on a daily basis. Once the parasitaemia reached 8–10%, the culture was expanded.

RNA Extraction and Microarray

RNA extraction and hybridizations were performed according to Ref. 14. For the hybridization, a P. falciparum oligonucleotide microarray was used consisting of 10,166-long oligonucleotide elements for 5363 genes with one unique oligonucleotide every 2 kb/gene (15). Total RNA was prepared directly from frozen pellets of parasitized erythrocytes (10 different TP of W2mef and W2mef/NM (parasite strain grown in neuraminidase-treated rbc), respectively), 1 ml of cell pellet was lysed in 10 ml of TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen), and RNA was extracted according to the manufacturer's instructions. For the hybridization experiments, 12 μg of total pooled reference RNA (W2mef parasites of all developmental intraerythrocytic stages) or sample RNA (single TP W2mef or W2mef/NM) was used for first strand cDNA synthesis. Samples from individual TP of either W2mef or W2mef/NM (coupled to Cy5) (Amersham Biosciences) were hybridized against the W2mef reference pool (coupled to Cy3) (Amersham Biosciences). Microarray hybridizations were incubated for 14–16 h using a Maui hybridization system (Bio Micro Systems). cDNA microarray hybridizations were performed in duplicate. The raw array data was stored and normalized using the NOMAD microarray database (http://ucsf-nomad.sourceforge.net/). The array features were unflagged, and those with median intensities greater than the local background plus two times the standard deviation of the background were extracted from the database.

Real Time PCR

5 μg of DNase-treated RNA was converted to cDNA using random primers (Invitrogen) and Superscript reverse transcriptase III (Invitrogen). The primers used for real time PCR are listed in supplemental Data Set 4.

Individual real time PCRs were carried out in 15-μl volumes using MiroAmp optical 8-tube strip (0.2 ml) with optical caps (Applied Biosystems) with 7.5 μl of Sybr Green master mix (Applied Biosystems), 6.4 μl of H2O, 10 μm forward and reverse primer (0.3 μl each), and 0.5 μl of gDNA or cDNA. The incorporation of fluorescent SYBR green dye (Applied Biosystems) was measured with an Applied Biosystems 7500 Real-Time PCR system using the cycling protocol 50 °C for 2 min, 95 °C for 10 min, 95 °C for 15 s, 58 °C for 1 min, 60 °C for 1 min, 95 °C for 15 s, 60 °C for 1 min, 95 °C for 15 s, and 60 °C for 15 s. Standards of 10-fold dilutions specific to the gene of interest were included in each run, and the Ct value at each dilution was measured. Because only single-copy genes are analyzed, standards were obtained by PCR amplification from W2mef genomic DNA using the same primers as in the real time PCR. The standards were quantified by spectrophotometry (Nanodrop). The product was specific and resulted in a single peak dissociation curve. In each real time PCR, H2O control and control without the SYBR green master mix were included. Each individual gene was analyzed in triplicate, and the Ct of each sample was recorded at the end of the reaction. The averages and S.D. of three Ct values per gene were calculated when the S.D. was <0.38 (16). To measure relative efficiency amplifications on the dilution series, a reference primer was used (housekeeping gene ornithine aminotransferase) and target genes. The average of the Ct for the reference gene and target gene was calculated, and ΔCt determined (ΔCt = Ct target gene − Ct reference gene). The log DNA dilution versus ΔCt was plotted. When the absolute value of the slope was <0.1, the relative quantification ΔΔCt was calculated for each gene as described by Livak and Schmittgen (17): ΔΔCt = (Ct target gene − Ct reference gene)W2mef/NM − (Ct target gene − Ct reference gene)W2mef. The results were plotted in fold change W2mef/NM versus W2mef.

Obtaining Free Merozoites

Essentially, the parasites were obtained as described by Blackman (12). Synchronized schizonts without erythrocytes were resuspended in RPMI 1640 with Albumax, placed back in culture flasks, gassed, and incubated at 37 °C. The culture was observed by Giemsa-stained smear. Once free merozoites were visible, the culture was transferred to a 50-ml centrifuge tube and centrifuged twice at 2400 rpm for 3 min. Supernatant was transferred to another 50-ml tube and centrifuged at 5000 rpm for 4 min. Subsequently, to remove all schizonts the merozoite pellet was immediately resuspended in RPMI 1640 without Albumax and passed through an amicon pressure unit (10 ml with a 2.0-μm isopore membrane filter; Millipore).

The pellet was observed by Giemsa-stained smear to ensure that only merozoites were present in the pellet. The pellet was washed twice in 500 μl of 1× PBS, then transferred into 1.5-ml Eppendorf tubes, and centrifuged at 5000 rpm for 4 min (Eppendorf centrifuge 5415 D). Finally the pellet was resuspended in 10 mm Tris-Cl and centrifuged at 5000 rpm for 4 min. The supernatant was removed, and the pellet was snap frozen in liquid nitrogen prior storage at −80 °C. For each merozoite protein preparation, merozoites from ∼12.4 × 109 schizonts were used, giving ∼1.98 × 1011 merozoites (assuming 16 merozoites/schizont).

Protein Extraction and Isobaric Labeling for iTRAQ

Three independent iTRAQ experiments were performed for statistical evaluation of the iTRAQ results. In each experiment, three independent cultures were pooled. The pelleted merozoites were resuspended in a buffer consisting of 500 mm triethylammonium bicarbonate, pH 8.5, 8 m urea, and a mixture of protease inhibitor mixture (Roche Applied Science). The sample was lysed and then centrifuged at 13,000 × g for 30 min at 4 °C, and protein was recovered in the supernatant. 200 μg of proteins from each pooled sample (W2mef/NM or W2mef) were reduced with 5 mm Tris-(2-carboxyethyl) phosphine for 1 h at 37 °C, and cysteine was alkylated with 10 mm of methylmethanethiosulfate for 10 min at room temperature. The sample was then diluted to 1 m urea for trypsin digestion. Trypsin (Promega) was added according to the ratio of 50:1 (protein:trypsin) and incubated overnight at 37 °C. The resulting peptides were dried and resuspended in 30 μl of 500 mm triethylammonium bicarbonate, pH 8.5, and 100 μl of ethanol. Each sample was divided into two equal portions and then isotopically labeled according to the manufacturer's protocol (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The labeling scheme was 114, W2mef/NM; 115, W2mef; 116, W2mef/NM; and 117, W2mef. The labeled samples were combined, dried, and stored at −80 °C until further MS analysis.

Strong cation exchange (SCX) Fractionation of Peptides

SCX chromatography was performed on a Shimadzu ProminenceTM UFLC unit (Kyoto, Japan) using a 200 × 4.6 mm (5-μm particle size, 200-Å pore size) PolySULFOETHYL ATM column (PolyLC, Columbia, MD). A 50-min gradient was used by a combination of 10 mm KH2PO4 in 25% acetonitrile, pH 2.85 (buffer A), and 500 mm KCl in 25% acetonitrile, pH 2.85 (buffer B). A total of 30 fractions were collected, lyophilized, and desalted using SEP-PAK C18 cartridges (Waters Corporation, Milford, MA). Eluents were lyophilized and stored at −80 °C before LC-MS/MS analysis.

Mass Spectrometry

The iTRAQ labeled samples were analyzed with a QStar Elite Q-TOF (Applied Biosystems, Framingham, MA) coupled with a Tempo nanoLC system. Each fraction of the iTRAQ-labeled samples was first trapped and desalted with Zorbax 300SB-C18 column and further separated with an integrated nano-bored C18 column, packed with Magic 5 μm C18 particles. The nanoLC flow rate was set at 300 nl/min with a 90-min LC gradient. The data acquisition was performed with Analyst QS 2.0 software (Applied Biosystems/MDS SCIEX). The mass spectrometer was set to perform data acquisition with a selected mass range of 300–1600 m/z. The three most abundant peptides (with +2 to +4 charge states) were selected for MS/MS analysis and dynamically excluded for 30 s with ±50 mmu tolerance. Smart information-dependent acquisition was activated with automatic collision energy and automatic MS/MS accumulation. The fragment intensity multiplier was set to 20, and the maximum accumulation time was 2 s. External mass calibration was performed using renin substrate tetradeca peptide (porcine, molecular mass = 1757.9 Da) (Sigma-Aldrich) before each iTRAQ experiment.

Data Analysis

The iTRAQ data was searched with ProteinPilot software v2.0.1 (Applied Biosystems/MDS-Sciex) for protein identification and quantification. The Paragon algorithm in the ProteinPilot software was used for the peptide identification and further processed by Pro Group algorithm where isoform-specific quantification was adopted to trace the differences between expressions of various isoforms. The defined parameters were as follows: (i) sample type: iTRAQ 4-plex (peptide labeled); (ii) cysteine alkylation: methylmethanethiosulfate; (iii) digestion: trypsin; (iv) instrument: QSTAR ESI; (v) special factors: none; (vi) species: none; (vii) specify processing: quantitate; (viii) ID focus: biological modifications, amino acid substitutions; (ix) database: a concatenated target-decoy database combining PlasmoDB P. falciparum (version 6.4), IPI human (version 3.34) and 156 commonly observed contaminants (146,588 sequences; 65884993 residues); and (x) search effort: thorough. Protein confidence was set at 95% confidence interval (equivalent to a ProtScore of 1.3). The peptide for quantification was automatically selected by Pro Group algorithm to calculate the reporter peak area, error factor, and p value. The resulting data set was auto bias-corrected to get rid of any variations imparted because of the unequal mixing during combining different labeled samples.

The iTRAQ results of the three independent experiments were exported from ProteinPilot as protein summary reports in Microsoft Excel file format; only P. falciparum proteins are used for further analysis (supplemental Data Set 1). The iTRAQ reporter ratios 115:114 (W2mef:W2mef/NM) and 117:116 (W2mef:W2mef/NM) with the corresponding p value and error factor of each iTRAQ experiment were calculated by built-in algorithm of ProteinPilot. The p value can be used to assess whether the changes in protein expression are statistically significant. The p value is a measure of the certainty of a change in the protein expression that is independent of the magnitude of the change. The false discovery rate of the identified protein (false discovery rate = (decoy hits/total hits) × 100%) was estimated based on the decoy search strategy and plotted in the protein summary report (supplemental Data Set 1). Approximately 677 P. falciparum proteins were identified with unused ProtScore > 1.3 (confidence > 95%); the corresponding false discovery rate is lower than 0.5% in each experiment (supplemental Data Set 1). Peptide MS/MS spectra of proteins identified with a peptide >95% confidence in each of the three experiments are shown in supplemental data.

Two sets, 115:114 (W2mef: W2mef/NM) and 117:116 (W2mef: W2mef/NM), of relative expression ratio of the two samples were measured in each experiment. The geometric mean of the iTRAQ reporter ratio and standard deviation (log ratios) of each identified protein from the six sets of iTRAQ ratio of the three independent experiments were calculated (supplemental Data Set 2).

Western Blot Analysis

W2mef and W2mef/NM snap frozen merozoite pellets were thawed on ice, resuspended in 100 μl of 2× SDS loading buffer. The lysate was separated on a 6 to 12% gradient acrylamide gel. Following electrophoresis, the acrylamide gels were transferred on nitrocellulose membrane (Bio-Rad) by Bio-Rad semidry transfer chamber with a buffer containing 1× Tris-glycine and 20% methanol for 30 min at 18 mV and then for another 30 min at 25 mV or by wet transfer for 2 h at 100 V. The membranes were blocked for 1 h at room temperature in 5% milk powder in TBST 0.05% (Tris-based saline with 0.05% Tween 20). All of the primary antibodies were diluted in the blocking buffer and incubated overnight at 4 °C, followed by three 10-min washes in TBST 0.05%. The dilutions for the primary and secondary antibodies are listed in supplemental Data Set 5. Secondary antibodies were diluted in blocking buffer, incubated for 1 h at room temperature, and washed three times in TBST 0.05% for 10 min. For detection, a Pierce chemiluminescence pico kit (Pierce) was used and exposed to Kodak medical x-ray film general green purpose or for higher sensitivity Amersham Biosciences hyperfilm TM ECL (GE Healthcare).

MSP-1 Invasion Inhibition Assay

MSP-1 rabbit antiserum was generated against affinity-purified full-length, native parasite MSP-1 purified in detergent (sodium deoxycholate) from mature T9/94 schizonts (18). Synchronized late stage schizonts of W2mef or W2mef/NM were purified by Percoll gradient, and 160 ml of parasite suspension was added in duplicate in a 96-well flat-bottomed microtiter plate (Iwaki) containing 40 ml of serial dilution from 1:10 to 1:200 of MSP-1 antiserum. The final hematocrit of NM-treated or untreated erythrocytes was 5%. 1000 erythrocytes were counted for the presence of rings on Giemsa-stained thin smears 24 h post-invasion. Invasion in the presence of antiserum was compared with positive control of invasion of the same parasite clones into normal erythrocytes in RPMI 1640 with Albumax. Invasion inhibition is presented relative to control in percentage of inhibition. The data shown are from two separate experiments.

Alternatively invasion inhibition was also determined by measuring lactate dehydrogenase. The lactate dehydrogenase assay was performed as previously described (19, 20) with some modifications. The invasion assays were performed in a 30-μl reaction volume with 2% hematocrit and 1% parasitemia (schizont stage) in the presence/absence of the anti-MSP1 antibody (1:50). The uninfected red blood cells without antibody were used as blank, and infected red blood cells without antibody were used as control. The Malstat and the NBT/PES solutions were prepared as described (19). The plated parasites were incubated for 35–40 h at 37 °C. After incubation, the parasites were lysed using a 20-min freeze/thaw process. This was followed by the addition of 100 μl of Malstat solution and 25 μl of NBT/PES solution. The sample was incubated in the dark for 1 h at room temperature. The absorbance was then measured at 620 nm.

RESULTS

Comparison of W2mef and W2mef/NM Merozoite Protein Expression during Invasion Pathway Switching

For the investigation of expressional changes, we took advantage of W2mef parasites utilizing either sialic acid-dependent (W2mef) or -independent (W2mef/NM) invasion pathways by selecting parasites to grow in NM-treated erythrocytes. Purified merozoites where obtained from W2mef as well as W2mef/NM for proteome analysis. Merozoite proteins were analyzed with a mass spectrometry-based quantitative proteomic technique, iTRAQ that determines the relative quantitative abundance of proteins. With this approach, multiple peptides per protein can be labeled, allowing high confidence in quantitation of the sample during MS/MS. Protein identities were obtained by searching the PlasmoDB P. falciparum database (version 6.4) by means of an in-house ProteinPilot software (version 2.01). Approximately 677 proteins were identified with higher than 95% confidence (Unused ProtScore > 1.3) from each independent experiment as shown in supplemental Data Set 1. The corresponding false discovery rate based on the decoy strategy was lower than 0.5%. The error factor and p value of reporter ratio was calculated by a build-in algorithm of ProteinPilot for statistical evaluation of the quantitative measurements.

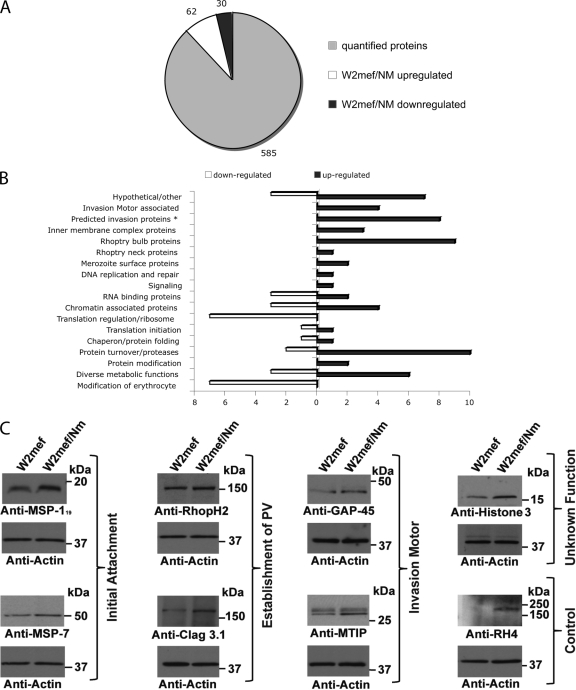

A total of 677 merozoite proteins were detected and gave high confident quantitative information (Fig. 1A and supplemental Data Set 1). These selected proteins were filtered with p value <0.05 or ≥2-fold difference in expression in W2mef/NM as compared with W2mef, and a total of 92 proteins showed significant change based on the selection criteria above in expression in W2mef/NM as compared with W2mef, with 30 proteins being down-regulated, whereas 62 proteins where up-regulated (Fig. 1A). The differentially regulated proteins were found to be grouped into diverse biological functions (Fig. 1B and Tables I and Table II) with the majority (Table I) comprising known invasion proteins, whereas proteins that could be broadly defined as playing a role in the regulation of expression either at the level of gene regulation, protein degradation, or modification (Tables I and II) constitute most of the remaining protein groups. Further confirmation of the quantitative results derived from the iTRAQ approach was obtained by semi-quantitative Western blot analysis using antibodies against RhopH2 (PFI1445w), Clag3.1 (PFC0110w), MSP7 (PF13_0197), MSP-119 (PFI1475w), MTIP (PFL2225w), GAP-45 (PFL1090w), RH4 (PFD1159c) and histone 3 (PF13_0185) (Fig. 1C). In all cases, the semi-quantitative Western blot data were consistent with the differences in expression observed between W2mef and W2mef/NM by iTRAQ.

Fig. 1.

Quantitative evaluation of merozoite proteins. A, merozoite proteins identified and quantified by iTRAQ technology. The circle diagram represents all 677 proteins identified for which quantitative data was obtained. 92 proteins were differentially regulated, with 62 up-regulated and 30 down-regulated proteins in W2mef/NM compared with W2mef as illustrated by the pie diagram. B, overview of function of differentially regulated proteins in W2mef/NM. C, validation of differential expression of selected proteins by Western blot. The increased expression of seven proteins (determined to be up-regulated in W2mef/NM using the iTRAQ system) and RH4 was validated by semi-quantitative immunoblot with specific antibodies against these merozoite proteins. Actin is used as a loading control.

Table I. List of up-regulated proteins in W2mef/NM from iTRAQ.

Proteins are arranged according to their function. The proteins in italics are below the cutoff at 2. These proteins are not included in the analysis but are stated here for the sake of completeness of functionally related proteins.

| Accession number | Name | Fold change W2mefNM/W2mef |

|---|---|---|

| Proteins associated with invasion | ||

| Surface proteins | ||

| PF13_0197 | Merozoite surface protein 7 precursor, MSP7 | 7.70 |

| PFI1475w | Merozoite surface protein 1, precursor | 2.57 |

| Rhoptry bulb proteins | ||

| MAL7P1.208 | Rhoptry-associated membrane antigen, RAMA | 2.53 |

| PF14_0102 | Rhoptry-associated protein 1, RAP1 | 2.35 |

| PFE0080c | Rhoptry-associated protein 2, RAP2 | 2.41 |

| PFE0075c | Rhoptry-associated protein 3, RAP3 | 2.10 |

| PFC0110w | RhopH1 (3.1) | 2.32 |

| PFC0120w | RhopH1 (3.2) | 2.17 |

| PFB0935w | Cytoadherence-linked asexual protein 2 | 2.06 |

| PFI1730w | Cytoadherence-linked asexual protein 9 (CLAG9) | 1.67 |

| PFI1445w | RhopH2 | 2.33 |

| PFI0265c | RhopH3 | 2.43 |

| Rhoptry neck protein | ||

| PF14_0495 | Rhoptry neck protein 2 (RON2) | 1.75 |

| MAL8P1.73 | Rhoptry neck protein 5 (RON5) | 1.92 |

| PFB0680w | Rhoptry neck protein 6 (RON6) | 1.66 |

| PFD0295c | Apical sushi protein, ASP | 2.26 |

| Inner membrane complex proteins | ||

| PFE1285w | Membrane skeletal protein IMC1-related | 2.77 |

| PF10_0039 | Membrane skeletal protein IMC1-related | 2.49 |

| PF14_0578 | Hypothetical protein | 2.07 |

| Predicted invasion proteins (25) | ||

| PF08_0119 | Conserved Plasmodium protein, unknown function | 4.73 |

| PF10_0119 | Hypothetical protein (apical location) | 3.98 |

| PFD0720w | Hypothetical protein (apical location) | 2.10 |

| PF10_0170 | Hypothetical protein | 2.59 |

| PF10_0166 | Hypothetical protein, conserved (surface staining) | 2.76a |

| PFB0475c | Hypothetical protein, conserved (apical location) | 2.13 |

| PFC0160w | Binding protein, putative | 2.17 |

| PFB0194w | Hypothetical protein, conserved | 2.86 |

| Invasion motor associated | ||

| PFL2225w | Myosin A tail domain interacting protein MTIP, putative | 3.90 |

| PFL1090w | Gliding-associated protein 45, GAP45 putative | 1.79 |

| PF13_0233 | Myosin A | 2.59 |

| PFL2460w | Coronin | 2.64 |

| PFE0165w | Actin depolymerizing factor, putative | 2.12 |

| Proteins associated to expression control | ||

| RNA-binding proteins | ||

| PF11_0280 | Small nuclear ribonucleoprotein F, putative | 4.26 |

| PFI1435w | RNA-binding protein, putative | 2.44 |

| PF13_0058 | RNA-binding protein, putative | 1.97 |

| Chromatin-associated proteins | ||

| PFF0860c | Histone h2a | 2.44 |

| PF13_0185 | Histone h3, putative | 1.71 |

| MAL8P1.72 | High mobility group protein, putative | 2.13 |

| PF11_0062 | Histone H2B | 1.97 |

| PFL0145c | High mobility group protein | 2.38 |

| PFI1260c | Histone deacetylase | 2.34 |

| Protein turnover/proteases | ||

| PFI1545c | Proteasome precursor, putative | 3.86 |

| PF07_0112 | Proteasome subunit α type 5, putative | 2.74 |

| PF11_0162 | Falcipain-3 | 2.33 |

| MAL8P1.142 | Proteasome β-subunit | 2.30 |

| PF14_0077 | Plasmepsin 2 | 2.08 |

| PF14_0075 | Plasmepsin IV | 2.76 |

| PF11_0142 | Ubiquitin domain-containing protein | 2.31 |

| PFE0380c | Nuclear pore-associated protein (NLP4), putative | 2.03 |

| PFC0520w | 26 S proteasome regulatory subunit S14, putative | 2.16 |

| MAL8P1.128 | Proteasome subunit alpha, putative | 2.29a |

| PFL1245w | Ubiquitin-activating enzyme e1, putative | 1.99 |

| PF14_0676 | 20 S proteasome β4 subunit, putative | 1.89 |

| Translation initiation | ||

| PFL0210c | Eukaryotic initiation factor 5a, putative | 2.05 |

| Protein modification | ||

| PF14_0660 | Protein phosphatase, putative/protein modification | 2.40 |

| PF14_0036 | Acid phosphatase, putative | 2.97 |

| DNA replication and repair | ||

| PF14_0316 | DNA topoisomerase II, putative | 2.05 |

| Chaperones | ||

| PF11_0164 | Peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans-isomerase | 2.34 |

| Other proteins | ||

| Signaling | ||

| PF14_0323 | Calmodulin | 2.63 |

| Diverse metabolic functions | ||

| PF14_0545 | Thioredoxin | 2.93 |

| PFE0660c | Purine nucleotide phosphorylase, putative | 2.37 |

| PF10_0155 | Enolase | 2.54 |

| PFE0625w | Rab1b, GTPase | 2.93a |

| PFC0190c | EH (Eps15 homology) protein (clathrin-mediated transport) | 2.18a |

| PF14_0378 | Triose-phosphate isomerase | 2.26 |

| Hypothetical/other | ||

| PFD1110w | Hypothetical membrane protein | 2.31 |

| PF11_0287 | Hypothetical protein | 2.07 |

| PFF0570c | Conserved Plasmodium protein, unknown function | 3.63 |

| PFL1945c | Early transcribed membrane protein 12, ETRAMP12 | 2.04 |

| PF10_0138 | Hypothetical protein, conserved | 2.64 |

| MAL13P1.32 | MORN repeat protein, putative | 2.16 |

| PFD0900w | Hypothetical protein, conserved | 2.63 |

a S.D. < 0.5.

Table II. List of down-regulated proteins in W2mef/NM from iTRAQ.

The proteins are arranged according to their function. These proteins are not included in the analysis but are stated here for the sake of completeness of functionally related proteins.

| Accession number | Name | Fold change W2mef/W2mefNM |

|---|---|---|

| Proteins involved in expression control and other proteins | ||

| RNA-binding proteins | ||

| PF10_0063 | DNA/RNA-binding protein, putative | 4.14a |

| PF14_0364 | Cleavage and polyadenylation specificity factor protein, putative | 2.01 |

| PFL1735c | RNA-processing protein, putative | 2.04 |

| Chromatin-associated proteins | ||

| PF10_0075 | Transcription factor with AP2 domain(s), putative | 2.38 |

| PF13_0095 | DNA replication licensing factor mcm4-related | 2.04 |

| PF14_0350 | Histone N-acetyltransferase, putative | 2.16 |

| Translation regulation/ribosome | ||

| PF13_0224 | 60 S ribosomal subunit protein L18, putative | 1.96 |

| PF14_0579 | Ribosomal protein L27, putative | 2.2 |

| PFF0700c | 60 S ribosomal protein L19, putative | 2.51 |

| PFF0625w | Nucleolar GTP-binding protein 1, putative | 2.61 |

| PF11_0106 | 60 S ribosomal protein L36, putative | 2.14 |

| PF11_0043 | 60 S acidic ribosomal protein p1, putative | 3.82 |

| PFE0185c | 60 S ribosomal subunit protein L31, putative | 2.69a |

| PFC0290w | 40 S ribosomal protein S23, putative | 9.15a |

| Translation initiation | ||

| PFL0310c | Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 3 subunit 8, putative | 2.21 |

| Protein turnover/proteases | ||

| PFI0580c | Falstatin, putative | 2.30 |

| PFD0665c | 26 S proteasome aaa-ATPase subunit Rpt3, putative | 2.32a |

| Chaperones/protein folding | ||

| PFC0900w | T-complex protein 1 epsilon subunit, putative | 2.22 |

| Diverse metabolic functions | ||

| PF07_0129 | Acyl-CoA synthetase, PfACS5 | 2.18 |

| PF11_0301 | Spermidine synthase | 2.96 |

| PF13_0044 | Carbamoyl phosphate synthetase, putative | 2.12 |

| Hypothetical/other | ||

| MAL8P1.95 | Hypothetical protein, conserved | 3.32 |

| PFL1815c | Hypothetical protein, conserved | 2.28 |

| MAL8P1.52 | Hypothetical protein, conserved | 2.58 |

| Exported proteins | ||

| Modification of erythrocyte | ||

| MAL7P1.171 | Plasmodium exported protein, unknown function | 3.50 |

| PF11_0507 | Antigen 332, putative | 2.02 |

| PFI1735c | Ring exported protein, REX | 2.77 |

| PFE0065w | Skeleton-binding protein 1, PfSBP1 | 2.28 |

| MAL13P1.41 | Membrane-associated histidine-rich protein, MAHRP-1 | 2.17 |

| PFD0090c | Plasmodium exported protein (PHISTa) | 2.26 |

| PF14_0743 | Plasmodium exported protein (hyp15), unknown function | 3.59 |

a S.D. < 0.5.

Schizont Stage Transcriptional Analysis of Quantified Merozoite Proteins

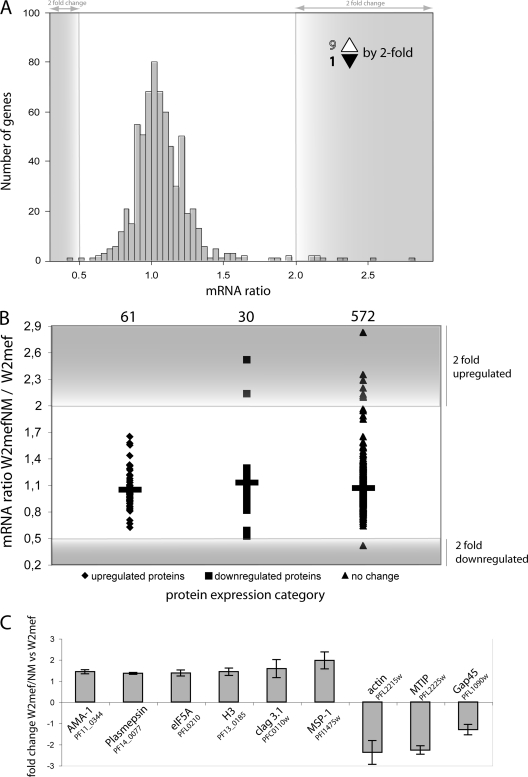

During schizont maturation, the parasite actively transcribes genes important for merozoite development and function. Schizont mRNA transcription has been used in many studies to correlate transcription and merozoite protein levels (5, 7, 21–23). Previous microarray studies comparing W2mef and W2mef/NM had indicated relatively few transcriptional differences. All of these studies compared only single schizont samples, so that small differences might have been undetected or overlooked (5, 7). To establish whether this was indeed the case, we used highly synchronous W2mef and W2mef/NM cultures and collected parasites at 2-h intervals through schizont maturation (32–48 h after invasion) for RNA extraction. To follow gene transcription during schizogony, each time point from W2mef and W2me/NM was hybridized against the reference pool (W2mef all stages) and analyzed (supplemental Data Set 3).

The transcriptional profiles of the 677 genes for which quantitative expression data had been obtained by iTRAQ (Fig. 1A) were compared. Here, of the 677 genes, 663 transcriptional profiles could be obtained with statistical significant data. Of the 663 genes, only one showed a more than 2-fold down-regulation, whereas 9 showed a greater than 2-fold up-regulation of transcript levels throughout schizont maturation (Fig. 2A). Importantly, none of the proteins that showed noteworthy changes in their expression levels had a corresponding change in transcript levels (Fig. 2B), indicating that post-transcriptional and post-translational regulation of protein expression plays an important role in regulating invasion pathway switching. This observation was furthermore confirmed by quantitative real time PCR (Fig. 2C). The majority of genes show no significant change in transcription profile (AMA-1, plasmepsin 2, eIF5a, histone 3, Clag3.1, and Gap-45) with only the transcript for MSP-1, actin, and MTIP showing a marginal 2-fold change. Overall, real time PCR confirms the microarray results that there are no differences in gene transcription between W2mef/NM and W2mef in the genes that show up-regulation in protein expression. The data presented here are from one of the most extensive analyses done for P. falciparum, providing evidence that post-transcriptional regulation is a key regulatory mechanism in Plasmodium.

Fig. 2.

Regulation of merozoite protein expression. A, distribution of mRNA ratios of genes with quantitative proteomic data. The mRNA ratio obtained from microarray analysis of W2mef/NM versus W2mef total of 663 genes follows the normal distribution. Only nine genes are show a more than 2-fold increase in transcription, whereas one shows a greater than 2-fold reduction in transcription (indicated in the gray area). B, transcriptional distributions of genes with protein expression data. W2mefNM/W2mef transcript ratios for proteins with quantitative expression data show that for none of the genes that are differentially transcribed is there a corresponding change at the protein level. No transcriptional changes are seen in proteins that show increased expression in W2mefNM (♦). For two genes that are transcriptionally up-regulated >2-fold in W2mefNM, the corresponding protein level is down-regulated (■), whereas a total of eight genes show significant transcriptional changes for proteins that are not differentially expressed (▴). C, validation of selected proteins by real time PCR. Gene transcription ratio of W2mef/NM versus W2mef of seven genes is given relative to housekeeping gene ornithine aminotransferase. The standard deviation of triplicates is indicated as an error bar. cDNA of combined 10 time points was used to generate the data.

Functional Clusters of Regulated Proteins

The analysis performed here allowed the identification and quantification of 677 proteins. Of the proteins that show a quantitative difference between W2mef and W2mefNM, proteins that play a direct role in the invasion process, as well as those regulating expression make up the most significant proportion (Fig. 1 and Tables I and II).

Invasion Proteins

Invasion proteins can be grouped based on their cellular location, into surface proteins, rhoptry bulb, rhoptry neck, and microneme proteins (24). In addition proteins making up the molecular motor driving the invasion process can also be considered part of the invasion machinery. Of the 62 proteins that are up-regulated in W2mefNM, 23 are known invasion proteins (24), whereas an additional four proteins have recently been predicted to be involved in merozoite invasion (25). In contrast, no invasion protein shows any increased expression in W2mef.

Of the three microneme proteins identified, none showed any changes in the expression levels between W2mef and W2mefNM, whereas only two (MSP1 and MSP7) of the eight merozoite surface proteins quantified showed any up-regulation in this study. In contrast, nine of the eleven rhoptry bulb proteins detected are up-regulated in W2mefNM, with only rhoptry-associated leucine zipper-like protein 1 (MAL7P1.119) showing no change in expression and Clag9 showing a marginal increase (Table I and supplemental Table 1). The up-regulation of rhoptry neck proteins is not as pronounced, with only ASP and RON5 showing increases of expression of ∼2-fold (Table I). In addition, four proteins associated with the invasion motor and three that are part of the inner membrane complex also show increased expression in W2mefNM (Table I).

Expression Control

The second largest group of proteins that show differential expression in W2mef and W2mefNM can be broadly categorized as regulators of expression. In both W2mef and W2mefNM, different RNA-binding proteins and proteins involved in protein modification and DNA replication and repair show changes in expression (compare Tables I and II), and it will be interesting in the future to establish the exact role these processes play in invasion pathway switching. There is, however, a striking difference in the mechanisms used to regulate protein expression in W2mef as compared with W2mefNM. In W2mef, regulation of translation shows the most dramatic changes, with nine proteins playing a role in translation control showing significant up-regulation (Table II). This contrasts with W2mefNM, where proteins implicated in protein turnover (Table I) show increased expression. Five chromatin-associated proteins are also up-regulated in W2mefNM, and it is interesting to note that these proteins include one member of histone H2a and H2b, which are important for overall chromatin organization.

Other Proteins

There are a range of other proteins including chaperones, signaling molecules, proteins linked to diverse metabolic functions, as well as a few hypothetical proteins that also show different expression levels between W2mef and W2mefNM (Tables I and II). One of these, enolase, is of interest because it has recently been shown to be expressed at the surface of the merozoite and has been implicated similar to aldolase to perform some “moonlighting” function during invasion (26, 27). In W2mef, there also appears to be increased expression of proteins that are exported to the cytosol from the infected erythrocyte (Table II). Immunofluorescent assays using antibodies against PfSBP1 on purified merozoites do not confirm expression of PfSBP1 in merozoites (data not shown), suggesting that there may be slight differences contaminating erythrocyte material in the two merozoite preparations.

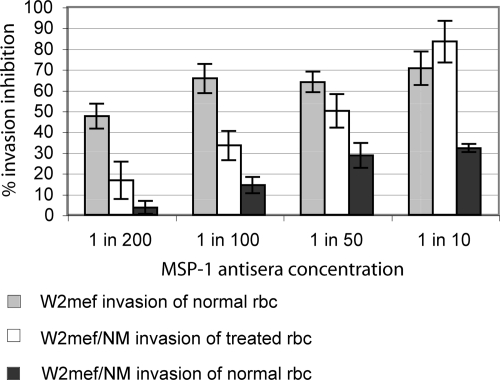

Physiological Relevance of Increased Expression of MSP-1

To establish whether increased expression of invasion proteins was of direct biological relevance for merozoite invasion, we analyzed the impact of invasion inhibitory antibodies targeting MSP-1 on W2mef and W2mef/NM. MSP-1 antibodies showed concentration-dependent inhibition of invasion. A 70–80% inhibition of invasion was achieved using a 1:10 dilution in W2mef invasion of untreated rbc and W2mef/NM invasion of NM-treated rbc (Fig. 3). Strikingly, invasion of W2mef/NM into untreated rbc was considerably less inhibited by anti-MSP1 antisera with a maximum inhibition of ∼30% being observed at a 1:10 antisera dilution. This result would indicate that the merozoite is up-regulating MSP1 expression in W2mef/NM to adjust to changes on the rbc surface that reduce the efficiency of MSP1 function (possibly initial attachment). In such a situation, anti-MSP1 antibodies would be expected to have a similar effect on W2mef invading untreated rbc and W2mef/NM invading NM-treated rbc. In contrast, W2mef/NM parasites would have an excess of MSP1 available when invading untreated rbc, making it more difficult for the available MSP1 sera to inhibit invasion efficiently. Identical results showing decreased impact of anti-MSP1 antisera on the ability of W2mef/NM merozoites to invade untreated erythrocytes as compared with NM-treated erythrocytes were obtained using an alternative invasion inhibition assay measuring lactate dehydrogenase (supplemental Fig. 1).

Fig. 3.

MSP-1 invasion inhibition assay. The invasion of parasites into erythrocyte in the presence of different concentration of MSP-1 antisera was assessed. The invasion inhibition was plotted in relation to control parasite without antibody added. The error bars indicate the standard deviation. MSP-1 antibody dilution showed concentration-dependent inhibition of invasion. A 70–80% inhibition of invasion was achieved using a 1:10 dilution in W2mef invasion of untreated rbc and W2mef/NM invasion of NM-treated rbc. Notably, invasion of W2mef/NM into untreated rbc was considerably less inhibited by anti-MSP1 sera with a maximum inhibition of ∼30% being observed at a 1:10 antisera dilution.

DISCUSSION

The expression of an alternative invasion protein has been linked to differences in invasion pathways utilized by the merozoite of the malaria parasite. Importantly, P. falciparum laboratory isolates have been shown to be able to switch from one invasion pathway to another, giving the parasite the ability to adapt to changes in the host cell environment or alternatively evade immune pressure. The current understanding on invasion pathway switching is predominately based on differences in the expression of different members of the erythrocyte-binding ligand and RH families of invasion ligands. Post-transcriptional regulation of protein expression has been suggested to play an important role in regulation of expression in malaria parasites (28, 29). At this stage, we are only aware of one genome-wide study that has been carried out in Plasmodium to directly link changes in transcription to quantitative changes in protein expression (29). The switching observed in the P. falciparum clone W2mef from a sialic acid-dependent to a sialic acid-independent invasion pathway provides an ideal system to not only obtain a better understanding of the extent of post-transcriptional regulation but also to gain new insights into the interaction of different merozoite invasion proteins.

Comparison of the quantitative proteomic data with the corresponding transcriptional time course indicates that more than 10% (92 of 677) of the parasite proteins are post-transcriptionally regulated. This regulation can either occur at the level of protein synthesis or degradation (30, 31). In eukaryotic systems, different regulatory mechanisms ranging from protein degradation by ubiquitin-proteasome pathway, mRNA decay, alternative splicing, mRNA motifs in UTR, translational repression, natural antisense transcripts, as well as post-translational modifications of proteins have been described (32–34). Whether all of these mechanisms are utilized by Plasmodium to regulate expression is not yet known, although there is a body of evidence that supports their existence in malaria parasites (35–51).

Our data here would suggest that a number of different mechanisms are involved in the regulation of expression during invasion pathway switching. A number of RNA-binding proteins are differentially expressed in the switched parasite including a putative ALBA protein. Proteins of this family are associated with accumulation of translational silenced mRNA in P-granules in oocyst (52, 53). Besides direct accumulation of mRNA into silenced particles, the changes in the expression of proteins associated with the spliceosome, as well as the polyadenylation machinery, suggest regulation of expression via alterative splicing or RNA modifications. In addition, the up-regulation of proteases and proteins associated with the proteasome in W2mefNM could indicate that protein turnover plays an important part in the regulation of expression during invasion pathway switching. This is in contrast to W2mef, where changes in ribosome proteins as well as translation initiation indicate translation rates as a key regulatory mechanism. Although at this stage it is not clear how antisense transcripts regulate expression (38), it is noteworthy that some of the so far identified antisense tags overlap with identified up-regulated proteins in this present study: histone 2b, MSP-1 (38), RAP1, and calmodulin (47). Interestingly, antisense tags are over-represented in two functional classes, translation and proteolysis, and on the other hand, under-represented in mitochondrial genes (38, 47), which is consistent with the findings here that show post-transcriptional regulation of exactly those two functional classes of proteins. An open question is in what way the regulation takes place: does it promote degradation of target mRNA, inhibition of translation initiation, or in contrast, play a more progressive role by binding to either chromatin, its modifiers, or RNA polymerase II (42, 50)?

The only transcriptional changes in W2mefNM that directly result in increased protein expression involve the previously described activation of RH4 (5, 7). Recently, it has been shown that this activation of RH4 may be epigenetically regulated (54). In this context, it is particularly noteworthy that in W2mefNM there are a number of proteins associated with chromatin structure that change their expression, including histones H2A and H2B and a putative high mobility group protein. Interestingly, there are extra copies of H2A and H2B that are not up-regulated. In other organisms, changes in specific histones have been linked to changes in the accessibility of this region of chromatin to the transcription machinery (reviewed in Refs. 55–58), and a similar mechanism may act here as well. Equally, high mobility group protein, a nuclear factor that is involved in the modification of histones, has been implicated in playing a role in the transcriptional control of gene expression in the sexual stage of P. yoelii, and it is important in oocyst development in the mosquito (59). Its up-regulation during invasion pathway switching is consistent with the epigenetic regulation of the RH4 locus.

Although the approach used in this study has provided an abundance of information on the regulation of expression in P. falciparum, it has also provided significant new insights on the interplay of invasion proteins during invasion pathway switching. The fact that no changes in the expression of microneme proteins are detected would imply that the proteins located in this organelle are not directly involved in invasion pathway switching. Rather the fact that all rhoptry bulb and the majority of the rhoptry neck proteins detected show increased expression in W2mefNM suggests that it is the coordinated expression of these proteins that is the key defining invasion pathway utilized by P. falciparum.

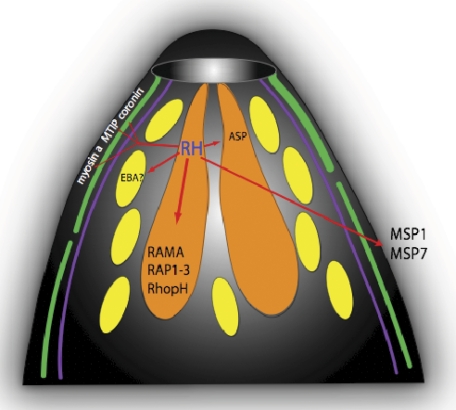

The increased expression of PfRH4, a rhoptry neck protein, is a key feature of invasion pathway switching from W2mef to W2mefNM, and depending on the study there may be a small (6) or no reduction (5, 7) in the expression of any of the other members of the PfRH family. This would lead to an increase in the total amount of PfRH in the rhoptry, and it is tempting to speculate that it is the need to maintain a stoichiometric relationship between PfRH and the other rhoptry proteins that is underlying the increase in rhoptry protein expression (Fig. 4). The up-regulation of all but two rhoptry bulb proteins including members from high molecular mass complex: RhopH1 (Clag2, Clag3.1, and Clag3.2,), RhopH2, RhopH3, and low molecular mass complex (RAP1, RAP2, and RAP3), as well as RAMA suggests a tight quantitative relationship possibly caused by the formation of a PfRH complex. Recently, it has been reported that a large macromolecular protein association on the merozoite is formed by some members of the MSP family together with RHopH1, RhopH3, Rap1, and Rap2 (60). This finding strongly supports our hypothesis that the interplay of a number of invasion molecules is necessary for successful invasion; thus, changing some invasion parameters subsequently has an effect of all the interacting proteins. Furthermore, the roles of RhopH3 and RAP1 are known to be associated with RAMA and form a macromolecular RhopH-RAP-RAMA complex (61), and the formation of a larger complex that includes PfRH during a certain stage of the invasion process is likely. In addition, some of these proteins have an erythrocyte binding activity (RhopH3, RAP1, RAP2, and RAMA) (62–67), and their recruitment into a PfRH complex might enhance or stabilize overall binding to the erythrocyte during invasion. Such stabilization may define the irreversible commitment of the merozoite to the invasion process. The increased expression of PfRH in W2mefNM could also explain the increased expression of components of the invasion motor complex. Only the nonmembrane-associated parts are up-regulated (GAP45, MTIP, and myosin A), whereas Gap50 is not changed, and we are not detecting GAPM, the protein linking the glideasome-associated proteins to the inner membrane complex (68–74), nor do we detect MTRAP, the proposed linker molecule between the motor complex and the erythrocyte surface in merozoites (68). Only the soluble proteins aldolase (75) and actin that are important for the invasion motor do not change their expression levels, although this may reflect the fact that they are continuously recycled during junction movement and therefore do not need to increase. Furthermore, two possible regulatory proteins of motor function, coronin (76) and calmodulin (77), are also up-regulated in W2mefNM. The coordinated up-regulation of the motor complex along with PfRH indicates a possible role for PfRH in this link.

Fig. 4.

Model of the affect of abundant RH4 on other invasion molecules during invasion pathway switching. Cartoon of the merozoite apical prominence with RH4 as a key molecule during the invasion pathway switching from sialic acid-dependent to sialic acid-independent invasion. Up-regulation of RH4 in the rhoptry neck has an impact on the up-regulation of other invasion molecules (highlighted by red arrows) to maintain the balance and stoichiometry of the various interactions. The higher expression of RH4 influences the up-regulation of other rhoptry neck proteins (ASP), as well as rhoptry bulb proteins (RAMA, RAP1–3, and RhopH complex). No micronemal proteins appear affected. Proteins between the inner membrane complex and the parasite membrane that are involved in the actin-myosin motor are also enhanced, and so are proteins expressed on the merozoite surface coat (MSP1 and MSP7), which initialize the first contact to the host cell.

Only two merozoite surface proteins: MSP-1 and MSP-7, known to form a complex with each other, show increased expression in W2mefNM, indicating that invasion pathway switching has a less dramatic effect on the initial early interactions of the merozoite with a potential host cell. It does, however, support the suggestion that MSP-1 is important for enabling the merozoite to form the initial interaction with the erythrocyte, something that may be more difficult in neuraminidase-treated erythrocytes. Some part of this effect can be explained by the changed overall properties of the neuraminidase-treated erythrocytes, which exacerbate the whole invasion process. Importantly, the differential inhibition of invasion of W2mef versus W2mef/NM by antibodies targeting MSP-1 suggests an important physiological role mediated by changed expression levels of this protein.

In conclusion, the work presented here demonstrates the power of combining quantitative proteomics with microarray analysis for studying parasite biology. This study has allowed us to gain new insights into the regulation of gene expression in P. falciparum that would not have been observed by utilizing either technique on their own. Furthermore, we show that invasion pathway switching is a much more complex process that requires the coordinated expression of a range of proteins important in host cell recognition, the movement of the merozoite through the junction, as well as the establishment of the parasitophorous vacuole.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Anthony Holder (London, UK) for providing MSP7, Clag3.1, RhopH2, and MTIP antisera; Dr. Mike Blackman (London, UK) for providing MSP1 antisera; and Dr. Julien Rayner (Cambridge, UK) for GAP45 and MR4 for histone 3 antibodies. Georges Snounou and Susana Geifman Sochart are thanked for critical reading the manuscript. We thank Ramadoss Ramya for help with the data extraction.

Footnotes

* This work was supported by Academic Research Council Grant MLC3/03 and Biomedical Research Council of Singapore Grant 04/1/22/19/364. The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

This article contains supplemental Table 1, Fig. 1, and Data Sets 1–5.

This article contains supplemental Table 1, Fig. 1, and Data Sets 1–5.

1 The abbreviations used are:

- RH

- reticulocyte-binding protein homologue(s)

- NM

- neuraminidase

- TP

- time point

- rbc

- red blood cells

- iTRAQ

- isobaric tags for relative and absolute quantitation.

REFERENCES

- 1. Iyer J., Grüner A. C., Rénia L., Snounou G., Preiser P. R. (2007) Invasion of host cells by malaria parasites: A tale of two protein families. Mol. Microbiol. 65, 231–249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gaur D., Mayer D. C., Miller L. H. (2004) Parasite ligand-host receptor interactions during invasion of erythrocytes by Plasmodium merozoites. Int. J. Parasitol. 34, 1413–1429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dolan S. A., Miller L. H., Wellems T. E. (1990) Evidence for a switching mechanism in the invasion of erythrocytes by Plasmodium falciparum. J. Clin. Invest. 86, 618–624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Duraisingh M. T., Maier A. G., Triglia T., Cowman A. F. (2003) Erythrocyte-binding antigen 175 mediates invasion in Plasmodium falciparum utilizing sialic acid-dependent and -independent pathways. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 4796–4801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Stubbs J., Simpson K. M., Triglia T., Plouffe D., Tonkin C. J., Duraisingh M. T., Maier A. G., Winzeler E. A., Cowman A. F. (2005) Molecular mechanism for switching of P. falciparum invasion pathways into human erythrocytes. Science 309, 1384–1387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gao X., Yeo K. P., Aw S. S., Kuss C., Iyer J. K., Genesan S., Rajamanonmani R., Lescar J., Bozdech Z., Preiser P. R. (2008) Antibodies targeting the PfRH1 binding domain inhibit invasion of Plasmodium falciparum merozoites. PLoS Pathog. 4, e1000104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gaur D., Furuya T., Mu J., Jiang L. B., Su X. Z., Miller L. H. (2006) Upregulation of expression of the reticulocyte homology gene 4 in the Plasmodium falciparum clone Dd2 is associated with a switch in the erythrocyte invasion pathway. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 145, 205–215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Camus D., Hadley T. J. (1985) A Plasmodium falciparum antigen that binds to host erythrocytes and merozoites. Science 230, 553–556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dolan S. A., Proctor J. L., Alling D. W., Okubo Y., Wellems T. E., Miller L. H. (1994) Glycophorin B as an EBA-175 independent Plasmodium falciparum receptor of human erythrocytes. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 64, 55–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Triglia T., Duraisingh M. T., Good R. T., Cowman A. F. (2005) Reticulocyte-binding protein homologue 1 is required for sialic acid-dependent invasion into human erythrocytes by Plasmodium falciparum. Mol. Microbiol. 55, 162–174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Trager W., Jensen J. B. (1976) Human malaria parasites in continuous culture. Science 193, 673–675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Blackman M. J. (1994) Purification of Plasmodium falciparum merozoites for analysis of the processing of merozoite surface protein-1. Methods Cell Biol. 45, 213–220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mitchell G. H., Hadley T. J., McGinniss M. H., Klotz F. W., Miller L. H. (1986) Invasion of erythrocytes by Plasmodium falciparum malaria parasites: Evidence for receptor heterogeneity and two receptors. Blood 67, 1519–1521 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bozdech Z., Llinás M., Pulliam B. L., Wong E. D., Zhu J., DeRisi J. L. (2003) The transcriptome of the intraerythrocytic developmental cycle of Plasmodium falciparum. PLoS Biol. 1, e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hu G., Llinás M., Li J., Preiser P. R., Bozdech Z. (2007) Selection of long oligonucleotides for gene expression microarrays using weighted rank-sum strategy. BMC Bioinformatics 8, 350.1–350.13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Pfaffl M. W. (2001) A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 29, e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Livak K. J., Schmittgen T. D. (2001) Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods 25, 402–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Holder A. A., Freeman R. R. (1984) The three major antigens on the surface of Plasmodium falciparum merozoites are derived from a single high molecular weight precursor. J. Exp. Med. 160, 624–629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Nkhoma S., Molyneux M., Ward S. (2007) In vitro antimalarial susceptibility profile and prcrt/pfmdr-1 genotypes of Plasmodium falciparum field isolates from Malawi. Am. J. Tropical Med. Hygiene 76, 1107–1112 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Persson K. E., Lee C. T., Marsh K., Beeson J. G. (2006) Development and optimization of high-throughput methods to measure Plasmodium falciparum-specific growth inhibitory antibodies. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44, 1665–1673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cao J., Kaneko O., Thongkukiatkul A., Tachibana M., Otsuki H., Gao Q., Tsuboi T., Torii M. (2009) Rhoptry neck protein RON2 forms a complex with microneme protein AMA1 in Plasmodium falciparum merozoites. Parasitol. Int. 58, 29–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Taylor H. M., Grainger M., Holder A. A. (2002) Variation in the expression of a Plasmodium falciparum protein family implicated in erythrocyte invasion. Infect. Immun. 70, 5779–5789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wickramarachchi T., Devi Y. S., Mohmmed A., Chauhan V. S. (2008) Identification and characterization of a novel Plasmodium falciparum merozoite apical protein involved in erythrocyte binding and invasion. PLoS One 3, e1732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cowman A. F., Crabb B. S. (2006) Invasion of red blood cells by malaria parasites. Cell 124, 755–766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hu G., Cabrera A., Kono M., Mok S., Chaal B. K., Haase S., Engelberg K., Cheemadan S., Spielmann T., Preiser P. R., Gilberger T. W., Bozdech Z. (2010) Transcriptional profiling of growth perturbations of the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Nat. Biotechnol. 28, 91–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Pal-Bhowmick I., Mehta M., Coppens I., Sharma S., Jarori G. K. (2007) Protective properties and surface localization of Plasmodium falciparum enolase. Infect. Immun. 75, 5500–5508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Pal-Bhowmick I., Vora H. K., Jarori G. K. (2007) Sub-cellular localization and post-translational modifications of the Plasmodium yoelii enolase suggest moonlighting functions. Malar. J. 6, 45.1–45.7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Coulson R. M., Hall N., Ouzounis C. A. (2004) Comparative genomics of transcriptional control in the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Genome Res. 14, 1548–1554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Le Roch K. G., Johnson J. R., Florens L., Zhou Y., Santrosyan A., Grainger M., Yan S. F., Williamson K. C., Holder A. A., Carucci D. J., Yates J. R., 3rd, Winzeler E. A. (2004) Global analysis of transcript and protein levels across the Plasmodium falciparum life cycle. Genome Res. 14, 2308–2318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Greenbaum D., Colangelo C., Williams K., Gerstein M. (2003) Comparing protein abundance and mRNA expression levels on a genomic scale. Genome Biol. 4, 117.1–117.8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Pratt J. M., Petty J., Riba-Garcia I., Robertson D. H., Gaskell S. J., Oliver S. G., Beynon R. J. (2002) Dynamics of protein turnover, a missing dimension in proteomics. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 1, 579–591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Schrader E. K., Harstad K. G., Matouschek A. (2009) Targeting proteins for degradation. Nat. Chem. Biol. 5, 815–822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Belasco J. G. (2010) All things must pass: contrasts and commonalities in eukaryotic and bacterial mRNA decay. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 11, 467–478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Nilsen T. W., Graveley B. R. (2010) Expansion of the eukaryotic proteome by alternative splicing. Nature 463, 457–463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Braks J. A., Mair G. R., Franke-Fayard B., Janse C. J., Waters A. P. (2008) A conserved U-rich RNA region implicated in regulation of translation in Plasmodium female gametocytes. Nucleic Acids Res. 36, 1176–1186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Crabb B. S., Triglia T., Waterkeyn J. G., Cowman A. F. (1997) Stable transgene expression in Plasmodium falciparum. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 90, 131–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Fan Q., Li J., Kariuki M., Cui L. (2004) Characterization of PfPuf2, member of the Puf family RNA-binding proteins from the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. DNA Cell Biol. 23, 753–760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Gunasekera A. M., Patankar S., Schug J., Eisen G., Kissinger J., Roos D., Wirth D. F. (2004) Widespread distribution of antisense transcripts in the Plasmodium falciparum genome. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 136, 35–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hall N., Karras M., Raine J. D., Carlton J. M., Kooij T. W., Berriman M., Florens L., Janssen C. S., Pain A., Christophides G. K., James K., Rutherford K., Harris B., Harris D., Churcher C., Quail M. A., Ormond D., Doggett J., Trueman H. E., Mendoza J., Bidwell S. L., Rajandream M. A., Carucci D. J., Yates J. R., 3rd, Kafatos F. C., Janse C. J., Barrell B., Turner C. M., Waters A. P., Sinden R. E. (2005) A comprehensive survey of the Plasmodium life cycle by genomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic analyses. Science 307, 82–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Horrocks P., Newbold C. I. (2000) Intraerythrocytic polyubiquitin expression in Plasmodium falciparum is subjected to developmental and heat-shock control. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 105, 115–125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kyes S., Christodoulou Z., Pinches R., Newbold C. (2002) Stage-specific merozoite surface protein 2 antisense transcripts in Plasmodium falciparum. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 123, 79–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Lapidot M., Pilpel Y. (2006) Genome-wide natural antisense transcription: Coupling its regulation to its different regulatory mechanisms. EMBO Rep. 7, 1216–1222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Militello K. T., Dodge M., Bethke L., Wirth D. F. (2004) Identification of regulatory elements in the Plasmodium falciparum genome. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 134, 75–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Militello K. T., Refour P., Comeaux C. A., Duraisingh M. T. (2008) Antisense RNA and RNAi in protozoan parasites: working hard or hardly working? Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 157, 117–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Orfa Rojas M., Wasserman M. (1995) Stage-specific expression of the calmodulin gene in Plasmodium falciparum. J. Biochem. 118, 1118–1123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Parker R., Sheth U. (2007) P bodies and the control of mRNA translation and degradation. Mol. Cell 25, 635–646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Patankar S., Munasinghe A., Shoaibi A., Cummings L. M., Wirth D. F. (2001) Serial analysis of gene expression in Plasmodium falciparum reveals the global expression profile of erythrocytic stages and the presence of anti-sense transcripts in the malarial parasite. Mol. Biol. Cell 12, 3114–3125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Polson H. E., Blackman M. J. (2005) A role for poly(dA)poly(dT) tracts in directing activity of the Plasmodium falciparum calmodulin gene promoter. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 141, 179–189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ponts N., Yang J., Chung D. W., Prudhomme J., Girke T., Horrocks P., Le Roch K. G. (2008) Deciphering the ubiquitin-mediated pathway in apicomplexan parasites: A potential strategy to interfere with parasite virulence. PLoS One 3, e2386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Werner A. (2005) Natural antisense transcripts. RNA Biol. 2, 53–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Werner A., Carlile M., Swan D. (2009) What do natural antisense transcripts regulate? RNA Biol. 6, 43–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Mair G. R., Braks J. A., Garver L. S., Wiegant J. C., Hall N., Dirks R. W., Khan S. M., Dimopoulos G., Janse C. J., Waters A. P. (2006) Regulation of sexual development of Plasmodium by translational repression. Science 313, 667–669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Mair G. R., Lasonder E., Garver L. S., Franke-Fayard B. M., Carret C. K., Wiegant J. C., Dirks R. W., Dimopoulos G., Janse C. J., Waters A. P. (2010) Universal features of post-transcriptional gene regulation are critical for Plasmodium zygote development. PLoS Pathog. 6, e1000767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Jiang L., López-Barragán M. J., Jiang H., Mu J., Gaur D., Zhao K., Felsenfeld G., Miller L. H. (2010) Epigenetic control of the variable expression of a Plasmodium falciparum receptor protein for erythrocyte invasion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 2224–2229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Altaf M., Auger A., Covic M., Côté J. (2009) Connection between histone H2A variants and chromatin remodeling complexes. Biochem. Cell Biol. 87, 35–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Draker R., Cheung P. (2009) Transcriptional and epigenetic functions of histone variant H2A.Z. Biochem. Cell Biol. 87, 19–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Svotelis A., Gevry N., Gaudreau L. (2009) Regulation of gene expression and cellular proliferation by histone H2A.Z. Biochem. Cell Biol. 87, 179–188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Thambirajah A. A., Li A., Ishibashi T., Ausió J. (2009) New developments in post-translational modifications and functions of histone H2A variants. Biochem. Cell Biol. 87, 7–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Gissot M., Ting L. M., Daly T. M., Bergman L. W., Sinnis P., Kim K. (2008) High mobility group protein HMGB2 is a critical regulator of Plasmodium oocyst development. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 17030–17038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Ranjan R., Chugh M., Kumar S., Singh S., Kanodia S., Hossain M. J., Korde R., Grover A., Dhawan S., Chauhan V. S., Reddy V. S., Mohmmed A., Malhotra P. (2011) Proteome analysis reveals a large merozoite surface protein-1 associated complex on the Plasmodium falciparum merozoite surface. J. Proteome Res. 10, 680–691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Topolska A. E., Lidgett A., Truman D., Fujioka H., Coppel R. L. (2004) Characterization of a membrane-associated rhoptry protein of Plasmodium falciparum. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 4648–4656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Ndengele M. M., Messineo D. G., Sam-Yellowe T., Harwalkar J. A. (1995) Plasmodium falciparum: Effects of membrane modulating agents on direct binding of rhoptry proteins to human erythrocytes. Exp. Parasitol. 81, 191–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Pinzón C. G., Curtidor H., Bermúdez A., Forero M., Vanegas M., Rodríguez J., Patarroyo M. E. (2008) Studies of Plasmodium falciparum rhoptry-associated membrane antigen (RAMA) protein peptides specifically binding to human RBC. Vaccine 26, 853–862 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Ling I. T., Florens L., Dluzewski A. R., Kaneko O., Grainger M., Yim Lim B. Y., Tsuboi T., Hopkins J. M., Johnson J. R., Torii M., Bannister L. H., Yates J. R., 3rd, Holder A. A., Mattei D. (2004) The Plasmodium falciparum clag9 gene encodes a rhoptry protein that is transferred to the host erythrocyte upon invasion. Mol. Microbiol. 52, 107–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Sterkers Y., Scheidig C., da Rocha M., Lepolard C., Gysin J., Scherf A. (2007) Members of the low-molecular-mass rhoptry protein complex of Plasmodium falciparum bind to the surface of normal erythrocytes. J. Infect. Dis. 196, 617–621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Sam-Yellowe T. Y. (1993) Plasmodium falciparum: Analysis of protein-protein interactions of the 140/130/110-kDa rhoptry protein complex using antibody and mouse erythrocyte binding assays. Exp. Parasitol. 77, 179–194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Sam-Yellowe T. Y., Shio H., Perkins M. E. (1988) Secretion of Plasmodium falciparum rhoptry protein into the plasma membrane of host erythrocytes. J. Cell Biol. 106, 1507–1513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Baum J., Richard D., Healer J., Rug M., Krnajski Z., Gilberger T. W., Green J. L., Holder A. A., Cowman A. F. (2006) A conserved molecular motor drives cell invasion and gliding motility across malaria life cycle stages and other apicomplexan parasites. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 5197–5208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Bergman L. W., Kaiser K., Fujioka H., Coppens I., Daly T. M., Fox S., Matuschewski K., Nussenzweig V., Kappe S. H. (2003) Myosin A tail domain interacting protein (MTIP) localizes to the inner membrane complex of Plasmodium sporozoites. J. Cell Sci. 116, 39–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Green J. L., Martin S. R., Fielden J., Ksagoni A., Grainger M., Yim Lim B. Y., Molloy J. E., Holder A. A. (2006) The MTIP-myosin A complex in blood stage malaria parasites. J. Mol. Biol. 355, 933–941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Jones M. L., Kitson E. L., Rayner J. C. (2006) Plasmodium falciparum erythrocyte invasion: A conserved myosin associated complex. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 147, 74–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Kappe S. H., Buscaglia C. A., Bergman L. W., Coppens I., Nussenzweig V. (2004) Apicomplexan gliding motility and host cell invasion: Overhauling the motor model. Trends Parasitol. 20, 13–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Ménard R. (2001) Gliding motility and cell invasion by Apicomplexa: Insights from the Plasmodium sporozoite. Cell Microbiol. 3, 63–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Soldati-Favre D. (2008) Molecular dissection of host cell invasion by the apicomplexans: The glideosome. Parasite 15, 197–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Jewett T. J., Sibley L. D. (2003) Aldolase forms a bridge between cell surface adhesins and the actin cytoskeleton in apicomplexan parasites. Mol. Cell 11, 885–894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Tardieux I., Liu X., Poupel O., Parzy D., Dehoux P., Langsley G. (1998) A Plasmodium falciparum novel gene encoding a coronin-like protein which associates with actin filaments. FEBS Lett. 441, 251–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Vaid A., Thomas D. C., Sharma P. (2008) Role of Ca2+/calmodulin-PfPKB signaling pathway in erythrocyte invasion by Plasmodium falciparum. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 5589–5597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]