Abstract

Most cell culture systems grow and spread as contact-inhibited monolayers on flat culture dishes, but the embryonic stem cell (ESC) is one of the cell phenotypes that prefer to self-organize as tightly packed three-dimensional (3D) colonies. ESC also readily form 3D cell aggregates, called embryoid bodies (EB) that partially mimic the spatial and temporal processes of the developing embryo. Here, the rationale for ESC aggregation, rather than “spreading” on gelatin-coated or mouse embryonic fibroblast (MEF)-coated dishes, is examined through the quantification of the expression levels of adhesion molecules on ESC and the calculation of the adhesive forces on ESC. Modeling each ESC as a dodecahedron, the adhesive force for each ESC-ESC binding was found to be 9.1 × 105 pN, whereas, the adhesive force for ESC-MEF binding was found to be an order of magnitude smaller at 7.9 × 104 pN. We also show that E-cadherin is the dominating molecule in the ESC-ESC adhesion and blocking E-cadherin leads to a significant reduction in colony formation. Here, we mathematically describe the preference for ESC to self-assemble into ESC-ESC aggregates and 3D colonies, rather than to bind and spread on gelatin or MEF-coated dishes, and have shown that these interactions are predominantly due to E-cadherin expression on ESC.

Key words: embryonic stem cells, stem cell morphology, E-cadherin, beta-1 integrin, cell adhesive forces, quantitative flow cytometry

Introduction

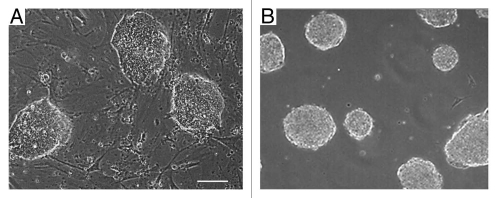

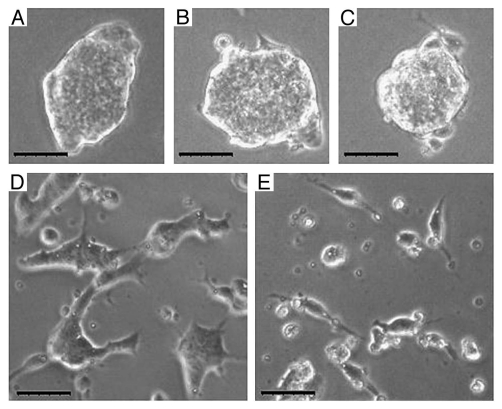

Many in vitro tissue cell culture systems classically grow as contact-inhibited monolayers on 2D tissue culture dishes. Conversely, the ESC cultures are morphologically distinct when cultured on these same surfaces. ESC form tightly packed 3D colonies in standard tissue culture dishes (Fig. 1A). These ESC colonies also readily and spontaneously assemble into unattached floating cell aggregates, called embryoid bodies (EB; Fig. 1B), which partially mimic the spatial and temporal processes of the developing embryo.1,2 We were interested in quantitatively exploring why the ESC prefer to adhere to one another and grow as 3D colonies compared with attaching and spreading on a flat surface like many other cell types.

Figure 1.

Embyryonic stem cell colonies grow as 3D structures. (A) Micrographs of dome-shaped murine embryonic stem cell (mESC) colonies growing on top of murine embryonic fibroblasts (MEF) and (B) embryonic stem cell (ESC) aggregates in forming embryoid bodies (EB) in suspension culture. Scale bar = 50 µm.

Cadherins

Calcium-dependent cell-cell adhesion junctions, called cadherins, are known to play a crucial role in a multitude of cellular processes including cell-cell adhesion, motility, and cell sorting in maturing organs and tissues.3 It has been thought that much of self-cell sorting is mediated through the expression of specific cadherin cell surface molecules, largely because the varying expression of cadherin proteins during ESC differentiation and between tissue-specific cell phenotypes. For example, vascular endothelial (VE) cadherin denotes the endothelial lineage, while neural (N) cadherin is present on neural cells. Alternatively, the primary cadherin expressed on murine ESC (mESC) is the epithelial (E) cadherin.4,5 Interestingly, E-cadherin is also the expressed on MEF6 and may pay a key role in the adhesion of ESC-to-MEF feeder cells in the ESC co-cultures. When cells expressing different cadherin molecules are co-cultured, the cells expressing E-cadherin will self-separate into distinct aggregates from the cells expressing N-cadherin.7 However, it has been more recently shown that both the cadherin quantity and affinity control tissue segregation.8

Integrins

Integrins are another family of adhesion proteins that exist as combinations of αβ subunits, largely distinguished by their β subunits: β1 (CD28), β3 (CD18), β5 (CD16), etc.9 Integrins are foremost molecules responsible for cell binding to extracellular matrix, as well as some cell-cell interactions crucial for many physiological processes signaling cell growth and differentiation. Their ability to bind ligand is regulated by cellular signaling mechanisms and involves conformational changes of the extracellular domains and/or changes in their cell surface distribution.10,11 It has been recently established that embryonic stem cells express a specific subset of integrins, all in the β1 family,12 which are also present on the MEF feeder cells.9,13

Tissue Morphogenesis

The spontaneous self-organization of cells and tissues is an intriguing phenomenon. The morphogenic process of “shifting of cell associations and subsequent segregation” into tissue arrangements was first described by Townes and Holtfreter14 and then later developed by Steinberg in 1994.15 The mechanisms that underlie these goal-directed rearrangements were suggested to be a combination of directed movements and selective adhesion, called the differential adhesion hypothesis (DAH).16 The DAH suggests that “mobile, cohesive subunits will spontaneously tend to rearrange so as to maximize their mutual adhesive bonding and the relative bonding energies.” According to DAH, the self-sorting process of individual entities do so with certain affinity for each other as a consequence of maximizing the ‘strength’ of mutual binding, thus minimizing the adhesive free energy of a system. Although DAH was formulated to explain the sorting and spreading behaviors of cells and tissues, it has been subsequently demonstrated to play a role in embryogenesis,17–20 wound healing,21 vasculogenesis22,23 and malignancy.24

Here, we quantitatively explore the relative roles of cadherins and integrins and their corresponding binding forces in order to mathematically describe the resulting 3D cell morphology of ESC colonies. Our method examines the expression levels of E-cadherin and Integrin-β1 on mouse ESC cultured on (a) the MEF feeder cells and (b) a gelatin substrate without feeders, as well as, the expression levels of these molecules on the MEF cells. The surface area for ESC-ESC binding is calculated by modeling the cell as a dodecahedron bordered by 12 other cells. The results mathematically describe the preference for ESC to self-assemble into ESC-ESC aggregates and 3D colonies, rather than to bind and spread on gelatin or MEFcoated dishes.

Results

ESC adhesion.

By modeling the ESC as a dodecahedron, it is possible to map out the adhesive forces acting on the “sides” of a cell. The dominant adhesion molecule expressed on an undifferentiated ESC is the E-cadherin.25 In addition, MEF also produce extracellular matrix molecules including laminin and fibronectin for integrin binding;26,27 therefore the integrin expression on ESC is also considered in the ESC binding to the MEF feeder layer. Other adhesion molecules are also present on ESC, but these will be shown to play a negligible role in the cell-cell adhesion of ESC compared with the cadherins and integrins.

Cell surface area.

The spherical ESC will be modeled as dodecahedrons with the following assumptions: the ESC are spherical in shape, tightly packed and exhibit close spherical regular packing such that each sphere is bordered by 12 other spheres.28,29 This dodecahedral model was chosen because it has the same packing as the regular spherical packing model, but also gives us a simple and nicely quantifiable cell-cell contact area. Although models like Kelvin's Conjecture30 and a slightly revised version provided by Weaire and Phelan31 suggest using a tetrakaidecahedron, these models focus on finding a solution to the tightly packed, space-filling, equivolumetric polyhedral of minimal surface area. However, the close packing of our cell aggregates require diffusion of nutrients, etc., and are therefore not as tightly packed as spheres made of inorganic materials.

The 12-sided 3-D shapes divide equilaterally and equiangularly in space. Also, the surface that adheres to neighboring cells, called a “face,” can be quantified based on cell size. When in a fluid suspension, the diameters of murine ESC range from 6 to 10 µm. Using the formula for the volume, V, of a sphere: V = (4/3)πr3, the following values are obtained (Table 1): for a 6 µm diameter cell: V = 113 µm3, for 8 µm: V = 268 µm3, and for 10 µm: V = 523 µm3. Next, we calculate the edge length of the dodecahedron model. This can be done by solving for ‘a’ in the following equation:

| (1) |

Table 1.

The surface area (SA) of a sphere and a dodecahedron were calculated for a range of cell sizes

| Diameter (µm) | Volume (µm3) | α (µm) | SA sphere (µm2) | SA dodecahedron (µm2) |

| 6 | 113 | 2.45 | 113 | 124 |

| 8 | 268 | 3.27 | 201 | 221 |

| 10 | 523 | 4.09 | 314 | 347 |

The differences between calculation methods vary by less than 10% for our range of cell sizes.

Using the edge length, the surface area, SA, of our cells can be calculated using the equation:

| (2) |

Using edge length for the dodecahedron, the estimations for the surface area of an ESC were calculated for three different sizes of stem cells using (1) the SA of a perfect sphere and (2) the SA for the dodecahedron. The data indicates that the SA measurements are 10% larger in the dodecahedron model compared with the SA of a perfect sphere (Table 1). Given the range of cell sizes present in mESC cultures, the differences in the calculated surface area between these two models are not statistically significant.

MEF synthesis of ECM.

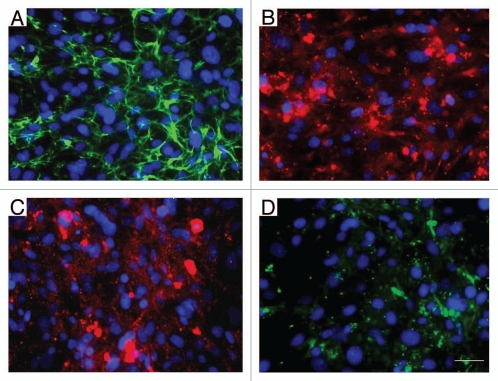

We first examined the ECM proteins produced by our MEF in order to verify that the appropriate ECM proteins were available for ESC integrin-β1 binding. The immunofluorescent analysis indicates that the MEF layer actively produces the ECM proteins fibronectin and, to a lesser extent, laminin, collagen type I and type IV (Fig. 2), verifying that these cells are generating specific sites for ESC integrin binding.

Figure 2.

Mouse embryonic fibroblasts synthesize various extracellular matrix proteins. Extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins produced by MEF cells include: (A) fibronectin, (B) laminin, (C) collagen-type I and (D) collagen-type IV. Scale bar = 50 µm.

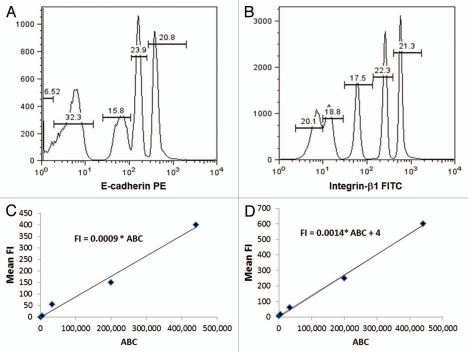

Antibody binding capacity of E-cadherin and integrin-β1 expression.

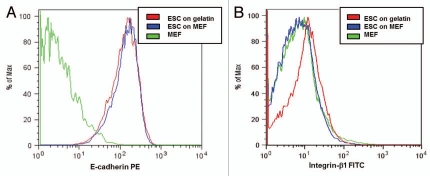

The ABC values for QSC microbeads stained with E-cadherin and integrin-β1 (Fig. 3A and B) were obtained by labeling the QSC microbeads with the corresponding antibodies that were also used to label the cells. From this data, we established correlations between ABC and fluorescence intensity (FI) values for each of the antibody labels (Fig. 3C and D). MEF and mESC (cultured on both MEF and gelatin) were then stained with identical E-cadherin and integrin-β1 antibodies. The mean fluorescence intensity (FI) values corresponding to the E-cadherin expression on MEF and ESC was then calculated. On MEF, the E-cadherin FI = 5, while FI = 140 and 160 for the ESC cultured on gelatin and on MEF-coated dishes respectively MEF-coated dishes respectively (from Fig. 4A). The procedure is repeated for the integrin β1 antibody. The mean FI value correlating to integrin-β1 expression on MEF was found to be FI = 4.7, while FI = 9.6 and 4.7 for ESC cultured on gelatin and MEF-coated dishes respectively (from Fig. 4B). The values were then inserted into the calibration equations (Fig. 3C and D) to obtain the ABC values for each molecule.

Figure 3.

The antibody binding capacity values correlate with fluorescence intensity values for specific monoclonal antibodies. (A and B) Histograms of the Quantum Simply Cellular (QSC) flow cytometry calibration microbeads stained with (A) PE-conjugated E-cadherin antibodies and (B) FITC-conjugated integrin-β1 antibodies. (C and D) The linear relationship of the measured mean fluorescence intensity (FI) values for a range of antibody binding capacities (ABC) on QSC flow cytometry calibration microbeads were obtained for QSC microbeads stained with (C) PE -conjugated E-cadherin antibodies and (D) FITC-conjugated integrin-β1 antibodies.

Figure 4.

ESC express larger numbers of E-cadherin molecules. Histograms of the mESC and MEF stained with (A) PE-conjugated E-cadherin antibodies and (B) FITC-conjugated integrin-β1 antibodies. The MEF do not express either molecule. The mESC express more integrin-β1 when cultured on gelatin (FI = 10) compare with when cultured on MEF (FI = 5, approximately equivalent to autofluorescence for the cells and calibration beads). The ESC express high levels of E-cadherin while cultured on MEF (mean FI = 139) or gelatin (mean FI = 148).

Modeling cell adhesion.

In order for the ESC-ESC to adhere one another more strongly than their MEF or ECM-coated surfaces, and grow vertically into a 3D colony, we expect that the adhesive forces between the ESC-ESC are greater than the adhesive forces between an ESC-MEF and its ECM.

| (3) |

where F2 represents the total adhesive force of ESC binding to the MEF feeder layer and ECM and F1 represents the total adhesive force for ESC-ESC binding. For simplification, the model assumes all adhesive forces are binding at their maximum strengths and that 100% of the available adhesive bonds are in their “bound” state. The maximum binding force of an E-cadherin/E-cadherin homophilic bond on mouse L-M(TK-) cells was measured to be 73 pN.7 The bond strength of an individual α5β1/fibronectin interaction on K562 cell lines was previously calculated to be 100 pN.32 We are assuming that these bonds strength values are relatively consistent across cell lines, and therefore, applicable to our ESC and MEF as well.

ESC-to-MEF adhesion.

The key components of the binding of ESC to MEF include E-cadherin/E-cadherin cell-cell adhesions, FE-cad, and ESC integrin-binding to ECM components, Fint.

| (4) |

Interestingly, MEF express very low levels of E-cadherin, under 2,000 ABC (calculated from Fig. 5A). Returning to the dodecahedron model where we consider 12 sides per ESC: 2,000 ABC/12 = 166 E-cadherin per “face” of the ESC.

Figure 5.

E-cadherin blocking reduces ESC-ESC contacts. Images of ESC colonies cultured (A–C) without E-cadherin blocking antibody and (D and E) with the blocking antibody. Note that the ESC colonies cultured with the blocking antibody are significantly smaller with more cells growing as single cells. Scale bar = 50 µm.

| (5) |

The ESC analyzed express β1-integrin molecules at a fairly low levels as well, under 500 ABC for ESC cultured on MEF and approximately 4,000 ABC for ESC cultured on gelatin. Because MEF are often plated on gelatin, the 4,000 ABC value is used for calculations. Returning to the dodecahedron model where we consider the 12 sides of an ESC binding to a MEF (and assuming that the ESC does not “spread” when binding to the MEF surface): 4,000/12 = 333 integrins on each “face” of the ESC. However, we also know that the integrins tend get recruited toward anchoring sites (i.e., the ECM binding surface), as well as contribute to the generation of focal adhesion complexes that can enhance adhesion strength by up to 30%.33 Due to integrin clustering, we estimate that we will have double the number of integrins at the binding surface: 2 × 333 = 666 integrins per binding “face.”34 If one “face” is in contact with the MEF layer and the maximum strength of an integrin bond is 100 pN:32,35,37

| (6) |

Thus,

| (7) |

ESC-to-ESC adhesion.

F1 represents the total adhesive force for ESC-ESC binding, due to cadherin-cadherin binding only. The quantitative flow cytometry data for E-cadherin expression on our mouse ESC indicates approximately 150,000 ABC of E-cadherin molecules per ESC regardless of whether they were cultured on MEF or on gelatin. The surface area of one pentagonal side of an ESC of approximately 8 µm in diameter is 221 µm2/12 = 18 µm2 and the maximum binding force of an E-cadherin/E-cadherin bond is 73 pN.7 Once again assuming that one side of an ESC binds to only one side of another ESC:

| (8) |

Note that we do not estimate for migration of E-cadherins toward the “binding face” because, unlike monolayer cultures, the E-cadherin/E-cadherin binding is expected to exist equally on all sides of the ESC, due to its 3D colony morphology.

E-cadherin and integrin blocking. The E-cadherin receptors on the ESC were blocked with an E-cadherin blocking antibody. After 48 h, the ESC with the E-cadherin blocking antibody exhibited significantly reduced colony sizes with many more ESC growing as single cells spreading on the culture dish (Fig. 5). Likewise, we expect that the blocking of β1-integrin on the ESC would interfere with the ESC-to-MEF binding. Although we did not run this experiment ourselves, a previous study has shown that β1-integrin null ESC did not adhere well on fibroblasts.38

Discussion

It is already well-known that the relative binding energies per unit area determine the most stable cell culture configurations.39 The presented calculations make use of this concept, estimating the adhesion forces between embryonic stem cells with each other and between embryonic stem cells and the fibroblasts feeders. Combining the known adhesive forces for each molecule with the measured number of molecules per cell allows new calculations of the relative adhesive forces between the ESC-ESC and ESC-MEF. The results indicate that the strength of adhesion of ESC-ESC, F1 = 9.1 × 105 pN, is an order of magnitude larger than the strength of adhesion of ESC-MEF, F2 = 7.9 × 104 pN, thus; mathematically describing the preference for ESC to adhere to each other in 3D colonies, rather than growing and spreading as monolayer cultures on MEF or gelatin-coated plates.

The examined cadherin and integrin adhesion molecules were carefully chosen due to their known expression levels on ESC. Although additional adhesion molecules such as: connexin-43,40 zona occluden-1 (ZO-1),41 platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule 1 (PECAM-1) 42 and EpCAM43,44 are often expressed on ESC, the integrins and cadherins are the dominating adhesion molecules on these cells. The cell separation force for E-cadherin, 30 nN, is an order of magnitude larger than the cell separation forces for occludins, 1 nN.45 Moreover, whether a specific receptor is considered and adhesion molecule at all depends on the magnitude of adhesive force and the time scale of the cell contact.46 Although PECAM-1, due to its tendency to localize at cell-cell borders, was originally described as an adhesion molecule, the primary role of PECAM-1 is in transmitting signals leading to an upregulation of β1 integrin function. It is now accepted that PECAM-1 itself cannot support strong adhesion.47 Connexin-43 is also expressed on the developing embryo for facilitation of intercellular coupling, cell morphology and very recently exhibited a role in the modulation of cell-cell assembly as well.48 EpCAM is the final known adhesion molecule that can be expressed on ESC, but the whole cell separation forces for this molecule could not be found in the literature. This body of literature indicates other adhesion molecules exist at lower levels or exhibit lower binding energies compared with E-cadherin and integrin-β1. In addition, our E-cadherin blocking study shows that the E-cadherin molecule is the most influential molecule determining the ESC colony-like morphology.

Integrin clustering and the presence of focal adhesion complexes on the ESC binding surface could also increase the strength of adhesion to the substratum by up to 30%.33 Although the presented calculations did account for integrin clustering (by doubling the number of integrins per binding surface), potential increases in binding strengths and affinities due to assembly of focal adhesions was not assessed in detail. If we consider that focal adhesions could increase the integrin binding forces by an additional 30%, our calculated value for ESC-MEF binding, F2, might be as large as 1 × 105 pN, but is still not a large enough force to overcome the F1 = 9.1 × 105 pN for ESC-ESC binding.

It has also been shown that integrins possess the ability to mediate strong intercellular cohesion when cells are grown as 3D aggregates.49 In this mechanism, the cell-cell cohesion enhances the adhesion and compaction of the cells in the 3D aggregate via a5β1-integrins, but fibronectin synthesis by the cells in the 3D aggregate is required for the integrin-ECM cohesion.49 Since the integrin-β1 expression on our ESC was measured to be very low, cohesion would not amount to a very large adhesive force in our ESC cultures.

This manuscript is the first of its kind to quantitatively explore the role of cadherins and integrins the cell morphology of ESC cultures. Here, the exploration of the relative binding forces of the cell-cell and cell-substratum (with and without MEF cocultures), the 3D cell morphology of ESC colonies is mathematically described. We have shown that the cell-cell adhesive forces of the ESC aggregates are much greater than the cell-substratum adhesive forces of the ESC and the E-cadherin molecule is responsible for the colony-like morphology of ESC, revealing mathematically, why these cells do not tend to spread significantly on the tissue culture plates.

Although the model presented in the manuscript was developed for homogeneous populations of ESC, we expect that the model would also remain valid for other types of homogeneous cell aggregates, including neurospheres—assuming that the neurospheres also contain homogeneous populations of neural progenitor cells. The model would only need to be altered for the different cell size, adhesion molecules and binding strengths. However, the model would not be applicable to cells in a developing embryo, embryoid body or differentiating neurosphere, since these cell aggregates contain inhomogeneous cell populations of varying sizes, morphologies and adhesion molecules.

Materials and Methods

Stem cell culture.

E14 murine ESC (generously donated from Dr. Bruce Conklin, UCSF) were cultured on either 0.5% gelatin coated-tissue culture plates or on mitotically inactivated MEF plated at 4 × 105 cells per 35 mm dish in chemically defined medium containing: 15% KnockOut Serum Replacement (KSR; Gibco), 1x Penicillin-Streptomycin (Invitrogen), 2 mM L-glutamine (Invitrogen), 1x Non-essential Amino Acids (Invitrogen), 0.1 mM β-mercaptoethanol (Calbiochem), 2,000 units/ml Leukemia Inhibitory Factor (LIF;Chemicon), 10 ng/ml bone morphogenic protein-4 (BMP-4; R&D Systems), and Knockout Dulbecco's Modified Essential Medium (KO-DMEM; Gibco). ESC were harvested using 1 ml of cell dissociation buffer (Invitrogen) per 35 mm dish for 20 min and separated from the MEF feeder layer by differential sedimentation of the MEF. The smaller and less sticky mESC are then removed with the supernatant. This separation method for removing MEF from ESC cultures consistently yields high purity mESC populations.

Immunofluorescent analysis of extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins.

The mitotically inactivated MEF were plated into 8-well chamber slides (Nunc) at 20,000 cells per well. Confluent MEF were subsequently labeled with unconjugated primary antibodies against rabbit polyclonal fibronectin, laminin, collagen I and collagen IV antibodies (Abcam) followed by an anti-rabbit PE or anti-rabbit FITC conjugated secondary antibody (Research Diagnostics). Images were recorded with a Leica DFC 350FX fluorescent microscope.

Quantification of adhesion molecules.

Antibody binding capacity (ABC) is a measure of the number of primary antibodies binding to a cell or microbead, and is linearly proportional to the number of specific surface molecules on a cell including the variables: valence of antibody binding, steric hindrance, binding affinity, and non-specific antibody binding. Thus we have:

| (9) |

where n1 is the number of binding sites per cell, including specific and non-specific binding sites (ns + nsp), ?1 is the fraction of binding sites on the surface bound by the primary antibody, and the parameter δ1 represents the valence of the primary antibody binding. The combined term is equivalent to the antibody binding capacity (ABC) of a cell population.50–52

Quantitative flow cytometry.

The Quantum Simply Cellular® microbeads (QSC, Bangs Laboratories) used in this study were uniform, 8.0 µm diameter, polystyrene microbeads with calibrated numbers of goat anti-mouse (GAM) antibodies bound to their surfaces. Individual sets of these microbeads are coated with four distinct populations of GAM antibodies by the manufacturer. These GAM antibodies bind the Fc region of IgG1, IgG2a and IgG2b isotypes of mouse monoclonal antibodies. The QSC microbeads used in this study expressed antibody binding populations of median ABC values of: 0, 5,400, 33,000, 200,000 and 440,000.

Cell staining.

Cells were then fluorescently labeled with either a rat monoclonal anti-mouse E-cadherin-PE conjugated antibody (R&D Systems) or a mouse monoclonal anti-integrin β1-FITC conjugated antibody (Abcam) using a buffer containing 0.5% bovine serum albumin (BSA), 2 mM EDTA, and phosphate buffered saline without calcium and magnesium (PBS). After staining, the cells were strained using a 70 µm cell strainer (BD Falcon) to ensure single cell suspensions. Flow cytometry analysis (FACS) was performed using a BD LSRII (Becton Dickinson) and data were analyzed using FlowJo software (TreeStar). For quantitative flow cytometric analysis, antibody binding capacity (ABC) was determined using Quantum Simply Cellular (QSC) anti-mouse IgG microbeads (Bangs Laboratories).53

E-cadherin blocking.

The E14 mESC were grown in serumfree maintenance medium on 0.5% gelatin-coated plates. The cells were then harvested using Cell Dissociation Buffer (Invitrogen), pelleted and resuspended in either serum-free maintenance medium or maintenance medium with E-cadherin blocking antibody (Invitrogen) at a 1:500 dilution. Individual wells in a 24-well plated are coated with. Cells were then seeded into 24-well plates coated with 0.5% gelatin at a 10,000 cells/cm2 and imaged using a phase contrast microscope after 48 h.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Basha Stankovich for her insight and valuable discussions regarding adhesion molecule expression on stem cells. This work was supported, in part, by an NIH-funded National Service Award from the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) #F31-HL087716.

References

- 1.Odorico JS, Kaufman DS, Thomson JA. Multilineage differentiation from human embryonic stem cell lines. Stem Cells. 2001;19:193–204. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.19-3-193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thomson JA, Itskovitz-Eldor J, Shapiro SS, Waknitz MA, Swiergiel JJ, Marshall VS, et al. Embryonic stem cell lines derived from human blastocysts. Science. 1998;282:1145–1147. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5391.1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Takeichi M. Cadherins: A molecular family important in selective cell-cell adhesion. Annu Rev Biochem. 1990;59:237–252. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.59.070190.001321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fuchs E, Segre JA. Stem cells a new lease on life. Cell. 2000;100:143–155. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81691-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Larue L. A role for cadherins in tissue formation. Development. 1996;122:3185–3194. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.10.3185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen F, Lu Y, Castranova V, Li Z, Karin M. Loss of ikkbeta promotes migration and proliferation of mouse embryo fibroblast cells. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:37142–37149. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603631200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Panorchan P, Thompson MS, Davis KJ, Tseng Y, Konstantopoulos K, Wirtz D. Single-molecule analysis of cadherin-mediated cell-cell adhesion. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:66–74. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duguay D, Foty RA, Steinberg MS. Cadherin-mediated cell adhesion and tissue segregation: Qualitative and quantitative determinants. Dev Biol. 2003;253:309–323. doi: 10.1016/S0012-1606(02)00016-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bates RC, Rankin LM, Lucas CM, Scott JL, Krissansen GW, Burns GF. Individual embryonic fibroblasts express multiple beta chains in association with the alphav integrin subunit. Loss of beta3 expression with cell confluence. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:18593–18599. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Humphries MJ, McEwan PA, Barton SJ, Buckley PA, Bella J, Mould AP. Integrin structure: Heady advances in ligand binding, but activation still makes the knees wobble. Trends Biochem Sci. 2003;28:313–320. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(03)00112-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shimaoka M, Salas A, Yang W, Weitz-Schmidt G, Springer TA. Small molecule integrin antagonists that bind to the beta2 subunit i-like domain and activate signals in one direction and block them in the other. Immunity. 2003;19:391–402. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(03)00238-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hayashi Y, Furue MK, Okamoto T, Ohnuma K, Myoishi Y, Fukuhara Y, et al. Integrins regulate mouse embryonic stem cell self-renewal. Stem Cells. 2007;25:3005–3015. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Popova SN, Rodriguez-Sanchez B, Liden A, Betsholtz C, Van Den Bos T, Gullberg D. The mesenchymal alpha11beta1 integrin attenuates pdgf-bb-stimulated chemotaxis of embryonic fibroblasts on collagens. Dev Biol. 2004;270:427–442. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Townes PL, Holtfreter J. Directed movements and selective adhesion of embryonic amphibian cells. J Exp Zool. 1955;128:53–120. doi: 10.1002/jez.1401280105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Steinberg MS, Takeichi M. Experimental specification of cell sorting, tissue spreading, and specific spatial patterning by quantitative differences in cadherin expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:206–209. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.1.206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Steinberg MS. Differential adhesion in morphogenesis: A modern view. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2007;17:281–286. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2007.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davis GS, Phillips HM, Steinberg MS. Germ-layer surface tensions and “tissue affinities” in rana pipiens gastrulae: Quantitative measurements. Dev Biol. 1997;192:630–644. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1997.8741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Foty RA, Pfleger CM, Forgacs G, Steinberg MS. Surface tensions of embryonic tissues predict their mutual envelopment behavior. Development. 1996;122:1611–1620. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.5.1611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hammerschmidt M, Wedlich D. Regulated adhesion as a driving force of gastrulation movements. Development. 2008;135:3625–3641. doi: 10.1242/dev.015701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schötz EM, Burdine RD, Julicher F, Steinberg MS, Heisenberg CP, Foty RA. Quantitative differences in tissue surface tension influence zebrafish germ layer positioning. HFSP J. 2008;2:42–56. doi: 10.2976/1.2834817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martin P, Parkhurst SM. Parallels between tissue repair and embryo morphogenesis. Development. 2004;131:3021–3034. doi: 10.1242/dev.01253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Adams RH, Wilkinson GA, Weiss C, Diella F, Gale NW, Deutsch U, et al. Roles of ephrinb ligands and ephb receptors in cardiovascular development: Demarcation of arterial/venous domains, vascular morphogenesis and sprouting angiogenesis. Genes Dev. 1999;13:295–306. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.3.295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pérez-Pomares JM, Mironov V, Guadix JA, Macias D, Markwald RR, Munoz-Chapuli R. In vitro selfassembly of proepicardial cell aggregates: An embryonic vasculogenic model for vascular tissue engineering. Anat Rec A Discov Mol Cell Evol Biol. 2006;288:700–713. doi: 10.1002/ar.a.20338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Foty RA, Steinberg MS. Cadherin-mediated cell-cell adhesion and tissue segregation in relation to malignancy. Int J Dev Biol. 2004;48:397–409. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.041810rf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kan NG, Stemmler MP, Junghans D, Kanzler B, de Vries WN, Dominis M, et al. Gene replacement reveals a specific role for e-cadherin in the formation of a functional trophectoderm. Development. 2007;134:31–41. doi: 10.1242/dev.02722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Amenta PS. Deposition of fibronectin and laminin in the basement membrane of the rat parietal yolk sac: Immunohistochemical and biosynthetic studies. J Cell Biol. 1983;96:104–111. doi: 10.1083/jcb.96.1.104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Geuskens M, Preumont AM, Van Gansen P. Fibronectin localization and endocytosis in early and late mouse embryonic fibroblasts in primary culture: A study by light and electron microscopic immunocytochemistry. Mech Ageing Dev. 1986;33:191–209. doi: 10.1016/0047-6374(86)90027-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krishna P. Introduction to close-packed structures in a 1st course in crystallography. Acta Crystallogr A. 1978;34:405–415. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sloane NJA. The packing of spheres. Sci Am. 1984;250:116–125. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican0184-116. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thomson W. Lxiii. On the division of space with minimum partitional area (reprinted) Philos Mag Lett. 2008;88:503–514. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weaire D, Phelan R. A counterexample to kelvin conjecture on minimal-surfaces. Philos Mag Lett. 1994;69:107–110. doi: 10.1080/09500839408241577. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li F, Redick SD, Erickson HP, Moy VT. Force measurements of the α5β1 integrin-fibronectin interaction. Biophys J. 2003;84:1252–1262. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74940-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gallant ND, Garcia AJ. Model of integrin-mediated cell adhesion strengthening. J Biomech. 2007;40:1301–1309. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2006.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hantgan RR, Lyles DS, Mallett TC, Rocco M, Nagaswami C, Weisel JW. Ligand binding promotes the entropy-driven oligomerization of integrin alphaiibbeta3. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:3417–3426. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208869200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Garcia AJ, Gallant ND. Stick and grip. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2003;39:61–73. doi: 10.1385/CBB:39:1:61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Litvinov RI, Shuman H, Bennett JS, Weisel JW. Binding strength and activation state of single fibrinogen-integrin pairs on living cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:7426–7431. doi: 10.1073/pnas.112194999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xiao Y, Truskey GA. Effect of receptor-ligand affinity on the strength of endothelial cell adhesion. Biophys J. 1996;71:2869–2884. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79484-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fässler R, Rohwedel J, Maltsev V, Bloch W, Lentini S, Guan K, et al. Differentiation and integrity of cardiac muscle cells are impaired in the absence of beta1 integrin. J Cell Sci. 1996;109:2989–2999. doi: 10.1242/jcs.109.13.2989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ryan PL, Foty RA, Kohn J, Steinberg MS. Tissue spreading on implantable substrates is a competitive outcome of cell-cell vs. Cell-substratum adhesivity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:4323–4327. doi: 10.1073/pnas.071615398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Park JH, Lee MY, Heo JS, Han HJ. A potential role of connexin 43 in epidermal growth factor-induced proliferation of mouse embryonic stem cells: Involvement of Ca2+/pkc, p44/42 and p38 mapks pathways. Cell Prolif. 2008;41:786–802. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2184.2008.00552.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chung Y, Klimanskaya I, Becker S, Li T, Maserati M, Lu SJ, et al. Human embryonic stem cell lines generated without embryo destruction. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;2:113–117. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Koestenbauer S, Zech NH, Juch H, Vanderzwalmen P, Schoonjans L, Dohr G. Embryonic stem cells: Similarities and differences between human and murine embryonic stem cells. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2006;55:169–180. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2005.00354.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lu TY, Lu RM, Liao MY, Yu J, Chung CH, Kao CF, et al. Epithelial cell adhesion molecule regulation is associated with the maintenance of the undifferentiated phenotype of human embryonic stem cells. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:8719–8732. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.077081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ng VY, Ang SN, Chan JX, Choo AB. Characterization of epithelial cell adhesion molecule as a surface marker on undifferentiated human embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells. 2010;28:29–35. doi: 10.1002/stem.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vedula SRK, Lim TS, Kausalya PJ, Lane EB, Rajagopal G, Hunziker W, et al. Quantifying forces mediated by integral tight junction proteins in cell-cell adhesion. Exp Mech. 2009;49:3–9. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bruinsma R. Les liaisons dangereuses: Adhesion molecules do it statistically. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:375–376. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.2.375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Newman PJ. The biology of pecam-1. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:25–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bao B, Jiang J, Yanase T, Nishi Y, Morgan JR. Connexon-mediated cell adhesion drives microtissue self-assembly. FASEB J. 2011;25:255–264. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-155291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Robinson EE, Zazzali KM, Corbett SA, Foty RA. Alpha5beta1 integrin mediates strong tissue cohesion. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:377–386. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Davis KA, Abrams B, Iyer SB, Hoffman RA, Bishop JE. Determination of cd4 antigen density on cells: Role of antibody valency, avidity, clones and conjugation. Cytometry. 1998;33:197–205. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0320(19981001)33:2<197::AIDCYTO14>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.McCloskey KE, Chalmers JJ, Zborowski M. Magnetophoretic mobilities correlate to antibody binding capacities. Cytometry. 2000;40:307–315. doi: 10.1002/1097-0320(20000801)40:4<307::AID-CYTO6>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.McCloskey KE, Zborowski M, Chalmers JJ. Measurement of cd2 expression levels of ifn-alpha-treated fibrosarcomas using cell tracking velocimetry. Cytometry. 2001;44:137–147. doi: 10.1002/1097-0320(20010601)44:2<137::AIDCYTO1093>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Serke S, van Lessen A, Huhn D. Quantitative fluorescence flow cytometry: A comparison of the three techniques for direct and indirect immunofluorescence. Cytometry. 1998;33:179–187. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0320(19981001)33:2<179::AIDCYTO12>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]