Abstract

Trauma such as burns induces a hypermetabolic response associated with altered central carbon and nitrogen metabolism. The liver plays a key role in these metabolic changes; however, studies to date have evaluated the metabolic state of liver using ex vivo perfusions or isotope labeling techniques targeted to specific pathways. Herein, we developed a unique mass balance approach to characterize the metabolic state of the liver in situ, and used it to quantify the metabolic changes to experimental burn injury in rats. Rats received a sham (control uninjured), 20% or 40% total body surface area (TBSA) scald burn, and were allowed to develop a hypermetabolic response. One day prior to evaluation, all animals were fasted to deplete glycogen stores. Four days post-burn, blood flow rates in major vessels of the liver were measured, and blood samples harvested. We combined measurements of metabolite concentrations and flow rates in the major vessels entering and leaving the liver with a steady-state mass balance model to generate a quantitative picture of the metabolic state of liver. The main findings were: (1) Sham-burned animals exhibited a gluconeogenic pattern, consistent with the fasted state; (2) the 20% TBSA burn inhibited gluconeogenesis and exhibited glycolytic-like features with very few other significant changes; (3) the 40% TBSA burn, by contrast, further enhanced gluconeogenesis and also increased amino acid extraction, urea cycle reactions, and several reactions involved in oxidative phosphorylation. These results suggest that increasing the severity of injury does not lead to a simple dose-dependent metabolic response, but rather leads to qualitatively different responses.

Keywords: hypermetabolism, metabolic flux analysis, liver, trauma and burns, rat, in vivo

Introduction

Hypermetabolism is characterized by an increase in resting energy expenditure, a negative nitrogen balance, and alterations in neuroendocrine control of glucose and lipid metabolism. Hypermetabolism typically occurs after severe trauma such as burns or major surgery, as well as in certain chronic illnesses, cancer, and infectious diseases (Bosaeus, 2008; Herndon and Tompkins, 2004; Schols, 2002; Schwenk et al., 1999; Schwenk and Macallan, 2000). One long-term consequence of hypermetabolism is a severe depletion of the patient’s lean body mass, which is associated with significant morbidity and mortality (Goldstein and Elwyn, 1989). Though various therapies can ameliorate this condition (Atiyeh et al., 2008; Hart et al., 2002; Jeschke et al., 2008; Pereira and Herndon, 2005), they cannot completely overcome the deleterious effects of hypermetabolism, and in many cases pose additional risks and cause undesirable side effects.

Detailed quantitative analyses of metabolism in disease states have been performed, in many instances with the help of isotopically labeled tracers (Cabral et al., 2008; Chen et al., 2003; Yarmush et al., 1999; Zhaofan et al., 2002), typically at the whole-body level. Although metabolic probing could be made minimally invasive, thus introducing little to no perturbation to the system, it could not clearly identify the role of individual organs and tissues in the overall response. To address this, several investigators have used an ex vivo perfusion approach (Yang et al., 2008a, 2008b), which isolates a specific organ or tissue from the rest of the organism, thus allowing determination of the role of intrinsic (e.g., enzyme activity changes) versus extrinsic (e.g., substrate load) factors in the metabolic response of a particular tissue. Ex vivo perfusion is also amenable to metabolic profiling and mass balance analysis, thus providing a comprehensive snapshot of the metabolic state at a particular time (Arai et al., 2001; Banta et al., 2005, 2007; Lee et al., 2000, 2003; Nagrath et al., 2007; Yokoyama et al., 2005). On the other hand, this approach may be subject to criticism because the organ is no longer in its physiological environment.

In this study, we developed an intermediate approach where we sampled blood streams going in and out of the liver, and also measured blood flow rates in situ. The metabolite concentration data were then used as input to a previously described mass balance model of liver metabolism (Banta et al., 2007; Lee et al., 2000) to derive the metabolic flux distribution in the liver in vivo. Using this method, we assessed the metabolic response of the liver in rat models of experimentally induced burn injury of increasing severity.

Methods

Burn Injury Protocol

Male CD rats (Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA) weighing 270–300 g (n ≥ 5 for each group) were housed singly in a temperature (25°C) and light-controlled room (12-h light–dark cycle). The animals were cared for in accordance with National Research Council guidelines. Experimental protocols were approved by the Subcommittee on Research Animal Care, Committee on Research, Massachusetts General Hospital. Water and chow were provided ad libitum. Animals were allowed to adjust to their new surroundings for at least 2 days prior to inception of the experiment. On Day 0, rats were randomized into three groups and anesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of ketamine (62.5 mg/kg of body weight) and xylazine (12.5 mg/kg of body weight). The dorsum of each rat was shaved with clippers, and those receiving a 40% total body surface area (TBSA) burn also had their abdomens shaved. Burn area was demarcated with a stencil and template on the dorsal (20% TBSA) and ventral surfaces (20% TBSA). Full-thickness burns were determined by duration of burn where less time is required for the thinner ventral surface skin (Baskaran et al., 2000; Carter et al., 2004; Lohmann et al., 1998; Walker and Mason, 1968). The dorsal burn was administered through a 10-s immersion in boiling water; the ventral burn was administered through a 5-s immersion in boiling water. Sham-treated control animals were handled identically, except that room temperature water was used. Animals were then immediately resuscitated with an intraperitoneal saline injection (2.5 mL/kg per rat/%TBSA) and allowed to recover in individual cages.

Measurement of Hepatic Flow Rates and Blood Sampling

It has been shown that whole-body parameters of hypermetabolism post-burn injury, including heart rate and temperature, are elevated and/or stable on post-burn day 4 for rats of this age (Izamis et al., 2009). Therefore, this time point was selected for the studies herein. On the third day following the burn injury, all rats were fasted overnight in preparation for blood sampling on the fourth day. Fasting served the purpose of creating a gluconeogenic state for unidirectional fluxes in the metabolic flux analysis (MFA) model.

On day 4 rats were anesthetized (62.5 mg/kg ketamine + 12.5 mg/kg xylazine) and the abdomen was shaved from sternum to groin. A transverse abdominal incision was made and the xyphoid process clamped and retracted to expose the proximal abdominal contents. The intestines were moved aside and the caudal lobes of the liver gently elevated to reveal the portal triad. A perivascular ultrasonic probe (Transonic Systems, Ithaca, NY) provided flow rates for the portal vein (PV) and hepatic artery (HA). The sum of flow rates into the liver was assumed to equal the flow rate out via the suprahepatic vena cava (SHVC).

Following flow rate measurements, a removable clamp was placed on the inferior hepatic vena cava, immediately distal to the liver, and caudal to the renal and adrenal vasculature. After a few minutes, gentle retraction of the liver revealed a markedly reduced SHVC blood volume. A 23G heparinized syringe was used to withdraw ~1 mL of blood at the confluence of the hepatic veins into the SHVC. This technique did not cause extraneous blood loss. The clamp was carefully removed. A 23G heparinized syringe was used to withdraw ~1 mL of blood from the PV. The site was clamped to prevent exsanguination post-sampling. To obtain a HA measurement, the abdominal aorta was rapidly isolated caudal to its bifurcation into the common iliacs and catheterized with a heparinized 18G catheter, again ~1 mL was collected. The liver was excised and the wet weight obtained.

Metabolite Analyses

MFA analysis required measurements of oxygen uptake rate, lactate, urea, glucose, ketone bodies, amino acids, and albumin. For hepatic oxygen consumption calculations, blood gases, and pH were measured using a Rapidlab Blood Gas Analyzer 865 (Siemens Bayer, Deerfield, IL). Standard reagent kits were used to determine plasma glucose (Stanbio, Boerne, TX,No. 1075–825), urea (Stanbio, Boerne, TX,No. 0580), and lactate (Trinity Biotech, Jamestown NY, No. 735-10). The ketone bodies acetoacetate and β-hydroxybutyrate were measured enzymatically, by following the appearance or disappearance of NADH upon the addition of β-hydroxybutyrate dehydrogenase (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), respectively. Nineteen of the common amino acids (except tryptophan) plus ornithine and ammonia were measured using a Waters HPLC apparatus (Waters Co., Milford, MA) as described elsewhere (Arai et al., 2001). ELISA techniques were used to detect albumin (Sigma) and insulin (Crystal Chem Inc., Downers Grove, IL, No. INSKR020). To determine whether injury to these organs had occurred, liver and kidney function tests, alkaline phosphatase (ALP), alanine transaminase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), total bilirubin, blood urea nitrogen, and creatinine, were measured using a Piccolo Comprehensive Metabolic Panel (Abaxis, Inc., Union City, CA). Status of complex lipids HDL, LDL, VLDL, cholesterol, and triacylglycerols were also examined with the Piccolo.

Data Preprocessing

An outlier analysis was performed for each variable utilizing box-and-whisker diagrams in MATLAB (The Mathworks, Natick, MA); this resulted in deletion of <1% of data. The missing extracellular metabolite concentrations were replaced by the median of the measurements from the other animals from each group, which is a standard procedure in data mining analysis (Witten and Frank, 2005). Fluxes were calculated as:

| (1) |

where F is the flow rate and c is the concentration for metabolite i in the designated vessel (SHVC, PV, or HA). A second outlier analysis was performed for the fluxes, and 58 fluxes out of 405 total were deleted. The average value for each flux (for each group) was calculated for use in MFA, as discussed below.

Metabolic Flux Analysis

MFA is based on fitting the measured set of fluxes to a stoichiometric model for the hepatic metabolic reaction network developed previously (Lee et al., 2000). This model captures the main biochemical reactions involved in central carbon and nitrogen metabolism under fasting conditions (Supplementary Fig. 1). Fasting is used to deplete glycogen stores so that glucose output reflects de novo gluconeogenesis without the confounding effects of glycogen breakdown. Furthermore, under this condition pyruvate dehydrogenase is inhibited, such that both glycogenolysis and pyruvate dehydrogenase fluxes can be set equal to zero. With respect to lipid metabolism, the model includes free fatty acids entering β-oxidation, but excludes complex lipid (e.g., lipoproteins, cholesterol and its derivatives) degradation pathways because of the difficulty to account for all lipid sources, including release from intrahepatic lipid stores. The mathematical model uses 35 metabolites (Supplementary Table I) and 61 chemical reactions (Table IV), and was implemented and solved using MATLAB software as previously described (Banta et al., 2005).

Table IV.

Effect of burn injury on hepatic metabolic fluxes in situ.

| In vivo fluxes (µmol/h/g liver) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | Reaction | Pathway | SHAM (n = 5) |

20% TBSA (n = 5) |

40% TBSA (n = 5) |

| 1 | Glucose 6-phosphate ↔ glucose | Gluconeogenesis | 93 ± 37 | 28 ± 17 | 124 ± 135 |

| 2 | Fructose 6-phosphate ↔ glucose 6-phosphate | Gluconeogenesis | 99 ± 86 | 58 ± 30 | 129 ± 101 |

| 3 | Fructose 1,6-bisphosphate ↔ fructose6-phosphate | Gluconeogenesis | 66 ± 28 | 29 ± 17a | 112 ± 64c |

| 4 | 2 Glyceraldehyde 3-P ↔ fructose 1,6-bisphosphate | Gluconeogenesis | 57 ± 26 | 27 ± 18 A | 108 ± 55B,c |

| 5 | Phosphoenolpyruvate + NADH ↔ glyceraldehyde 3-P | Gluconeogenesis | 95 ± 33 | 39 ± 34a | 205 ± 105B,c |

| 6 | Oxaloacetate ↔ CO2 + phosphoenolpyruvate | Gluconeogenesis | 90 ± 32 | 37 ± 35 a | 203 ± 100bc |

| 7 | Pyruvate + CO2 ↔ oxaloacetate | Gluconeogenesis | 31 ± 18 | 13 ± 30 | 151 ± 70bc |

| 8 | Lactate ↔ pyruvate + NADH | Lactate metabolism and TCA cycle | 5.6 ± 2.6 | −7.3 ± 7.0a | 87 ± 67bc |

| 9 | Acetyl-CoA + oxaloacetate → citrate | Lactate metabolism and TCA cycle | 68 ± 47 | 68 ± 11 | 120 ± 53C |

| 10 | Citrate ↔ 2-oxo-glutarate + NADH + CO2 | Lactate metabolism and TCA cycle | 75 ± 46 | 70 ± 12 | 123 ± 52C |

| 11 | 2-Oxo-glutarate → succinyl-CoA + NADH + CO2 | Lactate metabolism and TCA cycle | 92 ± 45 | 84 ± 11 | 148 ± 53c |

| 12 | Succinyl-CoA ↔ FADH2 + fumarate | Lactate metabolism and TCA cycle | 102 ± 44 | 89 ± 11 | 153 ± 58c |

| 13 | Fumarate ↔ malate | Lactate metabolism and TCA cycle | 140 ± 47 | 118 ± 34 | 235 ± 75b,c |

| 14 | Malate ↔ oxaloacetate + NADH | Lactate metabolism and TCA cycle | 145 ± 47 | 120 ± 32 | 238 ± 80B,c |

| 15 | Arginine → ornithine + urea | Urea cycle | 28 ± 23 | 25 ± 38 | 76 ± 34b,C |

| 16 | Ornithine + CO2 + NH4 ↔ citrulline | Urea cycle | 34 ± 19 | 32 ± 32 | 75 ± 29b,C |

| 17 | Citrulline + aspartate → arginine + fumarate | Urea cycle | 28 ± 20 | 27 ± 32 | 73 ± 29b,c |

| 18 | Arginine uptake | Amino acid metabolism | 3.6 ± 5.1 | 2.3 ± 1.8 | 2.8 ± 3.1 |

| 19 | Ammonia output | Urea cycle | −6.2 ± 1.7 | −5.3 ± 0.6 | −6.6 ± 1.6 |

| 20 | Ornithine output | Urea cycle | −3.4 ± 0.9 | −2.6 ± 2.5 | −0.1 ± 2.0b |

| 21 | Citrulline output | Amino acid metabolism | 5.6 ± 5.2 | 4.6 ± 3.1 | 2.2 ± 4.3 |

| 22 | Alanine → pyruvate + NH4 + NADH | Amino acid metabolism | 13 ± 6.7 | 21 ± 11 | 33 ± 9b |

| 23 | Alanine output | Amino acid metabolism | −13 ± 6.2 | −24 ± 10 A | −31 ± 8b |

| 24 | Serine → pyruvate + NH4 | Amino acid metabolism | 6.8 ± 11 | 1.6 ± 18 | 25 ± 16B,C |

| 25 | Serine uptake | Amino acid metabolism | 2.7 ± 1.7 | 4.8 ± 1.6 A | 6.4 ± 2.7b |

| 26 | Cysteine → pyruvate + NH4 + NADH | Amino acid metabolism | 0.8 ± 3.7 | −2.8 ± 5.9 | 3.3 ± 5.4 |

| 27 | Cysteine output | Amino acid metabolism | 0.2 ± 0.0 | 0 ± 0.1a | −0.3 ± 0.1b,c |

| 28 | Threonine → NADH + glycine + acetyl-CoA | Amino acid metabolism | 1.2 ± 4.0 | 2.4 ± 4.9 | 6.0 ± 3.2B |

| 29 | Glycine ↔ CO2 + NH4 + NADH | Amino acid metabolism | 4.2 ± 8.2 | 1.3 ± 13 | 18 ± 11B,C |

| 30 | Glycine uptake | Amino acid metabolism | 5.4 ± 1.2 | 7.1 ± 2.5 | 9.2 ± 2.6b |

| 31 | Valine + 2-oxo-glutarate → glutamate + propionyl-CoA + 3 NADH + FADH2 + 2 CO2 | Amino acid metabolism | 0.9 ± 0.4 | 1.2 ± 2.8 | −0.1 ± 0.4b |

| 32 | Isoleucine + 2-oxo-glutarate → glutamate + propionyl-CoA + acetyl-CoA + 2 NADH + FADH2 + CO2 | Amino acid metabolism | −0.2 ± 0.7 | 0.5 ± 1.3 | −0.3 ± 0.1 |

| 33 | Leucine + 2-oxo-glutarate → glutamate + NADH + FADH2 acetoacetate + acetyl-CoA | Amino acid metabolism | −0.2 ± 3.5 | 3.1 ± 3.1 | 5.4 ± 0.1b,C |

| 34 | Propionyl-CoA + CO2 > succinyl-CoA | Amino acid metabolism | 5.1 ± 2.0 | 3.6 ± 3.4 | 2.5 ± 6.1 |

| 35 | Lysine + 2 2-oxo-glutarate → 2 glutamate + 4 NADH + FADH2 + 2CO2 + acetoacetatyl-CoA | Amino acid metabolism | 1.5 ± 0.4 | 5.1 ± 5.7 | 4.6 ± 2.2b |

| 36 | Phenylalanine + O2 → tyrosine | Amino acid metabolism | 0.5 ± 0.4 | 2.2 ± 0.6a | 2.0 ± 1.0b |

| 37 | Tyrosine + 2 O2 → NH4 + CO2 + fumarate + acetoacetate + NADH | Amino acid metabolism | 3.7 ± 3.7 | 0.1 ± 5.4 | 6.4 ± 6.8 |

| 38 | Tyrosine output | Amino acid metabolism | −1.0 ± 1.1 | −1.0 ± 0.4 | −1.5 ± 0.3C |

| 39 | Glutamate ↔ 2-oxo-glutarate + NADH + NH4 | Amino acid metabolism | 15 ± 7.5 | 27.4 ± 13.7 | 37 ± 9b |

| 40 | Glutamate output | Amino acid metabolism | 0.8 ± 1.3 | 1.1 ± 1.1 | 1.0 ± 3.4 |

| 41 | Glutamine → glutamate + NH4 | Amino acid metabolism | 2.0 ± 2.5 | 4.0 ± 4.4 | 3.2 ± 0.5 |

| 42 | Proline + 0.5 O2 → glutamate + 0.5 NADH | Amino acid metabolism | 0.7 ± 2.9 | 4.8 ± 1.4a | 6.9 ± 3.4b |

| 43 | Histidine → NH4 + glutamate | Amino acid metabolism | 8.0 ± 5.3 | 8.0 ± 3.8 | 10.7 ± 3.3 |

| 44 | Methionine + serine → cysteine + NADH + propionyl-CoA + CO2 | Amino acid metabolism | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 0.9 ± 0.4 | 1.1 ± 0.4 |

| 45 | Aspartate ↔ oxaloacetate + NH4 + NADH | Amino acid metabolism | −24 ± 17 | −30 ± 26 | −68 ± 24b,C |

| 46 | Aspartate uptake | Amino acid metabolism | 0.5 ± 0.4 | 0.2 ± 0.3 | 0.5 ± 0.3C |

| 47 | Asparagine → aspartate + NH4 | Amino acid metabolism | 2.0 ± 1.1 | 0.9 ± 0.2A | 1.6 ± 0.4c |

| 48 | Palmitate → 8 acetyl-CoA + 7 FADH2 + 7 NADH | Lipid, glycerol, fatty acid metabolism | 11.1 ± 7 | 8.5 ± 4.2 | 11.8 ± 8 |

| 49 | 2 Acetyl-CoA ↔ acetoacetyl-CoA | Lipid, glycerol, fatty acid metabolism | 11 ± 16 | 2.9 ± 19 | 7.1 ± 14B |

| 50 | Acetoacetyl-CoA → acetoacetate | Lipid, glycerol, fatty acid metabolism | 15 ± 16 | 8.6 ± 18 | −1.6 ± 13 |

| 51 | Acetoacetate output | Lipid, glycerol, fatty acid metabolism | −1.3 ± 1.0 | 1.1 ± 2.7 A | 2.2 ± 0.7b |

| 52 | Acetoacetate + NADH ↔ b-hydroxybutyrate | Lipid, glycerol, fatty acid metabolism | 21 ± 16 | 11 ± 17 | 8.7 ± 9.1 |

| 53 | NADH + 0.5 O2 → NAD | Oxygen uptake and electron transport | 302 ± 181 | 327 ± 31 | 527 ± 205C |

| 54 | FADH2 + 0.5 O2 → FAD | Oxygen uptake and electron transport | 182 ± 87 | 158 ± 25 | 245 ± 97C |

| 55 | O2 uptake | Oxygen uptake and electron transport | 249 ± 132 | 247 ± 15 | 404 ± 148c |

| 56 | Glucose 6-phosphate → 2 NADPH + CO2 + ribulose 5-P | Pentose phosphate | 14 ± 90 | 32 ± 31 | 9.4 ± 134 |

| 57 | Ribulose 5-P ↔ ribose 5-P | Pentose phosphate | 3 ± 30 | 10 ± 11 | 2.3 ± 47 |

| 58 | Ribulose 5-P ↔ xylulose 5-P | Pentose phosphate | 18 ± 61 | 24 ± 19 | 10 ± 81 |

| 59 | Ribose 5-P + xylulose 5-P ↔ fructose6-P + erythrose 4-P | Pentose phosphate | 10 ± 30 | 12 ± 10 | 5.6 ± 40 |

| 60 | Erythrose 4-P + xylulose 5-P ↔ glyceraldehyde 3-P + fructose 6-P | Pentose phosphate | 15 ± 31 | 14 ± 9.1 | 8.2 ± 36 |

| 61 | CO2 output | Oxygen uptake and electron transport | 216 ± 30 | 191 ± 19 | 291 ± 20bc |

Values significantly different from sham group (P < 0.05).

Values significantly different from sham group (P < 0.1).

Values significantly different from 20% TBSA group (P < 0.05).

Values significantly different from 20% TBSA group (P < 0.1).

The model estimates otherwise inaccessible intracellular reaction fluxes by performing a mass balance around each intracellular metabolite using measured extracellular fluxes. Assuming pseudo steady-state conditions (intracellular concentrations of metabolites are constant), these mass balances reduce to a system of linear equations. This assumption is deemed acceptable because intracellular metabolites adapt quickly to metabolic changes, and there is no significant change in the metabolic state of the liver during data procurement (minutes).

Briefly, the sum of fluxes to and from a metabolite or its “pool” is assumed to be zero:

| (2) |

where the matrix S contains the stoichiometric coefficients of the biochemical reactions in the hepatic metabolic network. Each element Sij of S is the coefficient of metabolite i in reaction j, and each vj of vector v is the net flux or conversion rate of reaction j. Equation (1) is separated into measured (vm) and unknown fluxes (vu), as well as the matrices containing stoichiometric coefficients of known (Sm) and unknown reaction (Su) fluxes, as follows:

| (3) |

The measured fluxes represent rates of uptake or release of extracellular metabolites and by solving Equation (2) they also give estimates of unknown intracellular fluxes.

MFA was performed on each individual rat’s data, and the results in each group pooled to determine average ± standard deviation. The validity of the statistical model was confirmed via a consistency test (Wang and Stephanopoulos, 1983), at a threshold of P < 0.05. This method checks for the presence of gross errors that are inconsistent with other measurements, which lead to the violation of the pseudo steady-state assumption. Moreover, it can be used to identify the artifactual/erroneous measurements that lead to these inconsistencies. This approach was used to identify and eliminate five of 75 measurements required for oxygen consumption calculations.

Statistics

Comparisons were performed using a two-tailed Student’s t-test. The criterion for statistical significance was P < 0.05 for measured values of concentrations and flow rates (shown in Tables I and II). Flux values (shown in Tables III and IV and Figures 2–4) were compared using P < 0.1 and <0.05 as criteria for statistical significance.

Table I.

Measured in vivo hepatic blood flow and metabolite concentrations.

| Suprahepatic vena cava (SHVC, n = 5) | Portal vein (PV, n = 5) | Hepatic artery (HA, n = 5) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | SHAM | 20% TBSA |

40% TBSA |

SHAM | 20% TBSA |

40% TBSA |

SHAM | 20% TBSA |

40% TBSA |

| Blood flow (mL/min) | 15 ± 7.4 | 20 ± 9.1 | 20 ± 6.2 | 15 ± 7.4 | 19 ± 9.1 | 20 ± 6.3 | 0.66 ± 0.11 | 0.46 ± 0.05 | 0.46 ± 0.27 |

| Total hemoglobin (g/dL) | 13 ± 0.55 | 11 ± 1.4 | 11 ± 1.2 | 15 ± 1.2 | 13 ± 1.0 | 13 ± 0.41 | 13 ± 1.1 | 12 ± 0.94 | 9.9 ± 1.2* |

| Oxyhemoglobin (%) | 24 ± 3.3 | 34 ± 7.3 | 17 ± 6.1* | 73 ± 8.8 | 81 ± 5.1 | 75 ± 6.3 | 90 ± 4.9 | 92 ± 0.92 | 85 ± 3.6* |

| Partial O2 tension (mmHg) | 27 ± 0.63 | 41 ± 16 | 21 ± 6.2 | 68 ± 12 | 57 ± 12 | 66 ± 9.1 | 114 ± 27 | 115 ± 15 | 96 ± 13 |

| Partial CO2 tension (mmHg) | 52 ± 5.9 | 48 ± 7.8 | 67 ± 5.5* | 61 ± 12 | 62 ± 14 | 57 ± 2.0 | 45 ± 3.7 | 52 ± 11 | 48 ± 1.1 |

| Dissolved O2 (mL O2/100mL blood) | 4.2 ± 0.5 | 5.2 ± 1.2 | 2.7 ± 1.1* | 15 ± 2.5 | 14 ± 1.9 | 13 ± 0.9 | 15 ± 1.7 | 16 ± 1.1 | 12 ± 1.6* |

| Total CO2 (mmol/L) | 21 ± 2.8 | 22 ± 1.9 | 25 ± 0.45* | 19 ± 2.9 | 23 ± 0.71 | 23 ± 1.1 | 21 ± 1.1 | 20 ± 1.9 | 25 ± 1.8* |

| pH | 7.28 ± 0.01 | 7.29 ± 0.04 | 7.24 ± 0.02* | 7.27 ± 0.02 | 7.28 ± 0.05 | 7.25 ± 0.02 | 7.28 ± 0.03 | 7.29 ± 0.04 | 7.25 ± 0.02 |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 210 ± 57 | 165 ± 33 | 144 ± 12 | 123 ± 62 | 165 ± 30 | 125 ± 12* | 164 ± 57 | 141 ± 28 | 144 ± 18 |

| Lactate (mmol/L) | 1.0 ± 0.17 | 0.77 ± 0.17 | 4.3 ± 1.2* | 1.0 ± 0.18 | 0.75 ± 0.25 | 4.9 ± 0.84* | 0.94 ± 0.55 | 0.55 ± 0.16 | 3.5 ± 0.6* |

| β-Hydroxybutyric acid (µmol/L) | 350 ± 251 | 271 ± 141 | 216 ± 189 | 110 ± 96 | 124 ± 58 | 87 ± 47 | 245 ± 205 | 62 ± 23 | 141 ± 66 |

| Acetoacetic acid (µmol/L) | 116 ± 36 | 132 ± 12 | 11 ± 68* | 110 ± 73 | 143 ± 95 | 98 ± 88 | 122 ± 21 | 101 ± 67 | 61 ± 36 |

| Urea nitrogen (mg/dL) | 14 ± 5.0 | 15 ± 1.1 | 17 ± 2.0 | 13 ± 5.0 | 16 ± 2.2 | 16 ± 2.7 | 14 ± 4.3 | 13 ± 1.7 | 17 ± 2.6* |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 1.8 ± 0.17 | 1.2 ± 0.11 | 1.2 ± 0.09 | 1.9 ± 0.21 | 1.4 ± 0.13 | 1.3 ± 0.11 | 1.9 ± 0.10 | 1.1 ± 0.14 | 1.3 ± 0.17 |

| Ammonia (µmol/L) | 41 ± 3.4 | 29 ± 12 | 19 ± 5.7 | 109 ± 33 | 65 ± 30 | 74 ± 5.0 | 50 ± 5.4 | 38 ± 1.4 | 23 ± 2.4* |

| Alanine (µmol/L) | 261 ± 26 | 163 ± 29 | 149 ± 11 | 397 ± 13 | 401 ± 74 | 412 ± 69 | 357 ± 35 | 302 ± 14 | 284 ± 33 |

| Arginine (µmol/L) | 62 ± 1.5 | 198 ± 30 | 199 ± 23 | 141 ± 93 | 219 ± 36 | 222 ± 5.1 | 107 ± 7.9 | 195 ± 37 | 185 ± 11 |

| Ornithine (µmol/L) | 82 ± 9.9 | 85 ± 17 | 124 ± 11* | 120 ± 3.5 | 106 ± 3.3 | 128 ± 9.7* | 105 ± 20 | 117 ± 1.8 | 138 ± 21 |

| Asparagine (µmol/L) | 28 ± 0.83 | 21 ± 2.6 | 18 ± 0.07 | 49 ± 5.4 | 33 ± 2.5 | 31 ± 0.65 | 43 ± 3.4 | 35 ± 2.3 | 33 ± 3.4 |

| Aspartate (µmol/L) | 13 ± 0.88 | 11 ± 2.6 | 8.3 ± 0.62 | 21 ± 7.6 | 13 ± 0.54 | 13 ± 3.0 | 11 ± 1.2 | 8.6 ± 3.7 | 9.4 ± 2.0 |

| Cysteine (µmol/L) | 12 ± 0.46 | 17 ± 1.5 | 19 ± 1.9 | 15 ± 1.5 | 17 ± 1.5 | 17 ± 0.82 | 16 ± 1.2 | 21 ± 0.7 | 25 ± 1.1* |

| Glutamate (µmol/L) | 83 ± 19 | 51 ± 6.8 | 57 ± 18 | 68 ± 7.7 | 43 ± 6.7 | 53 ± 16 | 78 ± 5.2 | 46 ± 12 | 45 ± 9.0 |

| Glutamine (µmol/L) | 305 ± 42 | 221 ± 53 | 234 ± 8.6 | 293 ± 46 | 257 ± 29 | 255 ± 5.03 | 419 ± 36 | 359 ± 29 | 405 ± 15* |

| Glycine (µmol/L) | 194 ± 32 | 148 ± 5.3 | 124 ± 14* | 273 ± 27 | 216 ± 18 | 213 ± 25 | 218 ± 5.4 | 187 ± 17 | 163 ± 10* |

| Histidine (µmol/L) | 56 ± 6.6 | 50 ± 10 | 60 ± 7.1 | 137 ± 26 | 126 ± 14 | 148 ± 10* | 65 ± 0.17 | 59 ± 5.4 | 67 ± 3.5* |

| Proline (µmol/L) | 146 ± 21 | 114 ± 4.7 | 117 ± 14 | 163 ± 12 | 161 ± 6.7 | 177 ± 20 | 169 ± 5.6 | 147 ± 14 | 150 ± 7.5 |

| Serine (µmol/L) | 170 ± 12 | 107 ± 5.4 | 101 ± 15 | 199 ± 13 | 154 ± 24 | 153 ± 8.3 | 219 ± 24 | 159 ± 9.6 | 178 ± 19 |

| Methionine (µmol/L) | 38 ± 1.1 | 32 ± 1.9 | 34 ± 1.2 | 44 ± 7.0 | 43 ± 4.6 | 43 ± 1.8 | 54 ± 9.6 | 42 ± 4.1 | 40 ± 5.5 |

| Threonine (µmol/L) | 191 ± 24 | 167 ± 37 | 158 ± 7.5 | 204 ± 41 | 208 ± 39 | 211 ± 27 | 252 ± 40 | 221 ± 23 | 203 ± 15 |

| Valine (µmol/L) | 156 ± 54 | 191 ± 21 | 205 ± 18 | 165 ± 31 | 199 ± 20 | 205 ± 2.9 | 202 ± 69 | 193 ± 22 | 193 ± 27 |

| Tyrosine (µmol/L) | 60 ± 11 | 63 ± 9.6 | 67 ± 5.5 | 68 ± 7.4 | 74 ± 4.6 | 80 ± 5.3 | 80 ± 10 | 89 ± 1.6 | 82 ± 5.4* |

| Isoleucine (µmol/L) | 82 ± 7.5 | 97 ± 12 | 103 ± 11 | 86 ± 16 | 102 ± 6.3 | 101 ± 1.4 | 122 ± 28 | 106 ± 11 | 100 ± 19 |

| Phenylalanine (µmol/L) | 54 ± 2.8 | 52 ± 7.7 | 51 ± 2.9 | 59 ± 3.9 | 66 ± 2.9 | 66 ± 4.1 | 65 ± 4.4 | 63 ± 2.0 | 67 ± 1.1* |

| Leucine (µmol/L) | 241 ± 35 | 266 ± 33 | 240 ± 41 | 261 ± 33 | 310 ± 30 | 340 ± 13 | 321 ± 88 | 276 ± 33 | 290 ± 62 |

| Lysine (µmol/L) | 210 ± 42 | 201 ± 33 | 207 ± 24 | 220 ± 38 | 242 ± 23 | 270 ± 14 | 237 ± 42 | 193 ± 18 | 224 ± 1* |

| Sum amino acid nitrogen (µmol/L) | 3,683 | 3,845 | 3,873 | 4,880 | 5,039 | 5,313 | 4,809 | 4,640 | 4,759 |

Liver weights (g) in each group were SHAM: 9.4 ± 0.76; 20% TBSA: 10.6 ± 0.73; 40% TBSA: 9.83 ± 0.35.

Bolded items are significantly different (P < 0.05) from SHAM.

Value for 40% TBSA is significantly different (P < 0.05) compared to 20% TBSA burn.

Table II.

Non-MFA in vivo hepatic blood chemistry values.

| Suprahepatic vena cava (SHVC) | Portal vein (PV) | Hepatic artery (HA) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | SHAM (n = 12) |

20% TBSA (n = 12) |

40% TBSA (n = 13) |

SHAM (n = 12) |

20% TBSA (n = 12) |

40% TBSA (n = 13) |

SHAM (n = 12) |

20% TBSA (n = 12) |

40% TBSA (n = 13) |

| Insulin (ng/mL) | 1.1 ± 0.01 | 3.8 ± 0.02 | 4.5 ± 0.02* | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| AST (u/L) (87–114) | 96 ± 25.7 | 93 ± 26.8 | 122 ± 50.9 | 95 ± 30.0 | 110 ± 2.36 | 47 ± 45.4 | 109 ± 33.5 | 103 ± 37.6 | 116 ± 44.2 |

| ALT (u/L) (28–40) | 48 ± 13.0 | 39 ± 9.50 | 40 ± 7.30 | 53 ± 15.1 | 47 ± 7.20 | 43 ± 7.92 | 55 ± 15.7 | 40 ± 10.5 | 44 ± 9.87 |

| ALP (u/L) (136–188) | 209 ± 66.0 | 166 ± 63.0 | 165 ± 57.4 | 231 ± 81.7 | 188 ± 86.9 | 198 ± 58.9 | 259 ± 75.6 | 156 ± 93.5 | 186 ± 42.1 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) (0.1–1.0) | 0.32 ± 0.06 | 0.31 ± 0.03 | 0.32 ± 0.06 | 0.32 ± 0.06 | 0.34 ± 0.05 | 0.32 ± 0.06 | 0.32 ± 0.06 | 0.32 ± 0.04 | 0.35 ± 0.05 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) (0.5–0.6) | 0.25 ± 0.09 | 0.23 ± 0.049 | 0.22 ± 0.04 | 0.21 ± 0.03 | 0.22 ± 0.04 | 0.21 ± 0.03 | 0.21 ± 0.03 | 0.23 ± 0.05 | 0.25 ± 0.08 |

| Cholesterol (mg/dL) (55–89) | 62 ± 21.3 | 71 ± 19.7 | 68 ± 11.2 | 68 ± 20.0 | 86.4 ± 18.6 | 82 ± 8.50 | 72 ± 20.4 | 67 ± 22.2 | 74 ± 13.7 |

| HDL (mg/dL) | 33 ± 7.41 | 32 ± 8.4 | 32 ± 7.27 | 36 ± 3.15 | 42 ± 10.5 | 35 ± 3.56 | 32 ± 9.82 | 32 ± 11.6 | 34 ± 4.40 |

| LDL (mg/dL) | 28 ± 12.3 | 35 ± 14.9 | 32 ± 3.4 | 26 ± 11.1 | 37 ± 12.2 | 41 ± 6.94 | 30 ± 13.4 | 32 ± 15.0 | 39 ± 8.10 |

| VLDL (mg/dL) | 9 ± 3.3 | 5 ± 1.10 | 4 ± 0.45 | 11 ± 4.47 | 6 ± 1.33 | 5 ± 1.03 | 12 ± 3.24 | 7 ± 2.4 | 5 ± 0.89 |

| Triacylglycerol (mg/dL) (62–92) | 37 ± 17.0 | 22 ± 4.76 | 22 ± 2.38 | 48 ± 23.8 | 27 ± 8.15 | 24 ± 4.80 | 51 ± 21.2 | 31 ± 10.9 | 24 ± 4.53 |

Bolded items are significantly different (P < 0.05) from SHAM.

Value for 40% TBSA is significantly different (P < 0.05) compared to 20% TBSA burn.

Table III.

Hepatic metabolic fluxes measured in situ.

| Metabolite | SHAM (µmol/h/g) |

20% TBSA (µmol/h/g) |

40% TBSA (µmol/h/g) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oxygen uptake | 249 ± 132 | 247 ± 15 | 404 ± 148c |

| Carbon dioxide output | 216 ± 30 | 191 ± 228 | 291 ± 20b |

| Glucose output | 93 ± 37 | 28 ± 17a | 124 ± 135 |

| Lactate uptake | 5.6 ± 2.6 | −7.3 ± 7.0a | 87 ± 67b,c |

| Acetoacetate output | −1.3 ± 0.6 | 1.1 ± 2.7 | −2.2 ± 0.7b |

| β-Hydroxybutyrate output | 21 ± 16 | 11 ± 17 | 8.7 ± 9.1 |

| Urea output | 28 ± 23 | 25 ± 38 | 76 ± 34b |

| Ammonia uptake | 6.2 ± 1.7 | 5.3 ± 0.6 | 6.6 ± 1.6 |

| Alanine uptake | 13 ± 6.0 | 24 ± 10 | 31 ± 8.0b |

| Arginine uptake | 3.6 ± 5.1 | 2.3 ± 1.8 | 2.8 ± 3.1 |

| Ornithine uptake | 3.4 ± 0.9 | 2.6 ± 2.5 | 0.1 ± 2.0b |

| Asparagine uptake | 2.0 ± 1.1 | 0.9 ± 0.2a | 1.6 ± 0.4c |

| Aspartate uptake | 0.5 ± 0.4 | 0.2 ± 0.3 | 0.5 ± 0.3 |

| Cysteine output | 0.2 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.1a | −0.3 ± 0.1b,c |

| Glutamate output | 0.8 ± 1.3 | 1.1 ± 1.1 | 1.0 ± 3.4 |

| Glutamine uptake | 2.0 ± 2.5 | 4.0 ± 4.4 | 3.2 ± 0.5 |

| Glycine uptake | 5.4 ± 1.2 | 7.1 ± 2.5 | 9.2 ± 2.6b |

| Histidine uptake | 8.0 ± 5.3 | 8.0 ± 3.8 | 11 ± 3.3 |

| Proline uptake | 0.7 ± 2.9 | 4.8 ± 1.4a | 6.9 ± 3.4b |

| Serine uptake | 2.7 ± 1.7 | 4.8 ± 1.6 | 6.4 ± 2.7b |

| Methionine uptake | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 0.9 ± 0.4 | 1.1 ± 0.4 |

| Threonine uptake | 1.2 ± 4.0 | 2.4 ± 4.9 | 6.0 ± 3.2 |

| Valine uptake | 0.8 ± 0.4 | 1.2 ± 2.8 | −0.1 ± 0.4b |

| Tyrosine uptake | 1.0 ± 1.1 | 1.0 ± 0.4 | 1.5 ± 0.3 |

| Isoleucine uptake | −0.2 ± 0.7 | 0.5 ± 1.3 | −0.3 ± 0.1 |

| Phenylalanine uptake | 0.5 ± 0.4 | 2.2 ± 0.6a | 2.0 ± 1.0b |

| Lysine uptake | 1.5 ± 0.4 | 5.1 ± 5.7 | 4.6 ± 2.2b |

| Leucine uptake | −0.2 ± 3.5 | 3.1 ± 3.1 | 5.4 ± 0.1b,c |

Values significantly different from sham group (P < 0.05).

Values significantly different from 20% TBSA group (P < 0.05).

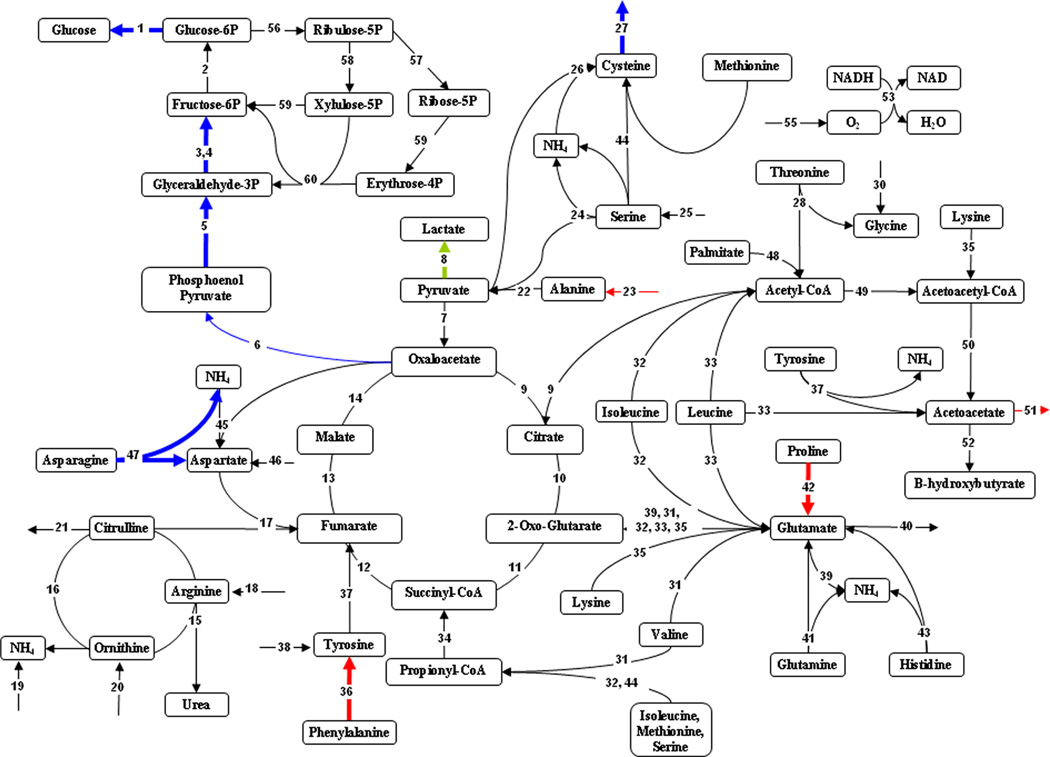

Figure 2.

Effect of 20% TBSA burn injury on hepatic metabolic fluxes compared to sham controls. Highlighted fluxes reflect differences in 20% TBSA burn results compared to sham (black). Fluxes in red are up-regulated, those in blue are down-regulated, and fluxes in green are reversed. Thick lines show changes that are significant at a level of P < 0.05. Thin lines show changes that are significant at a level of P < 0.1.

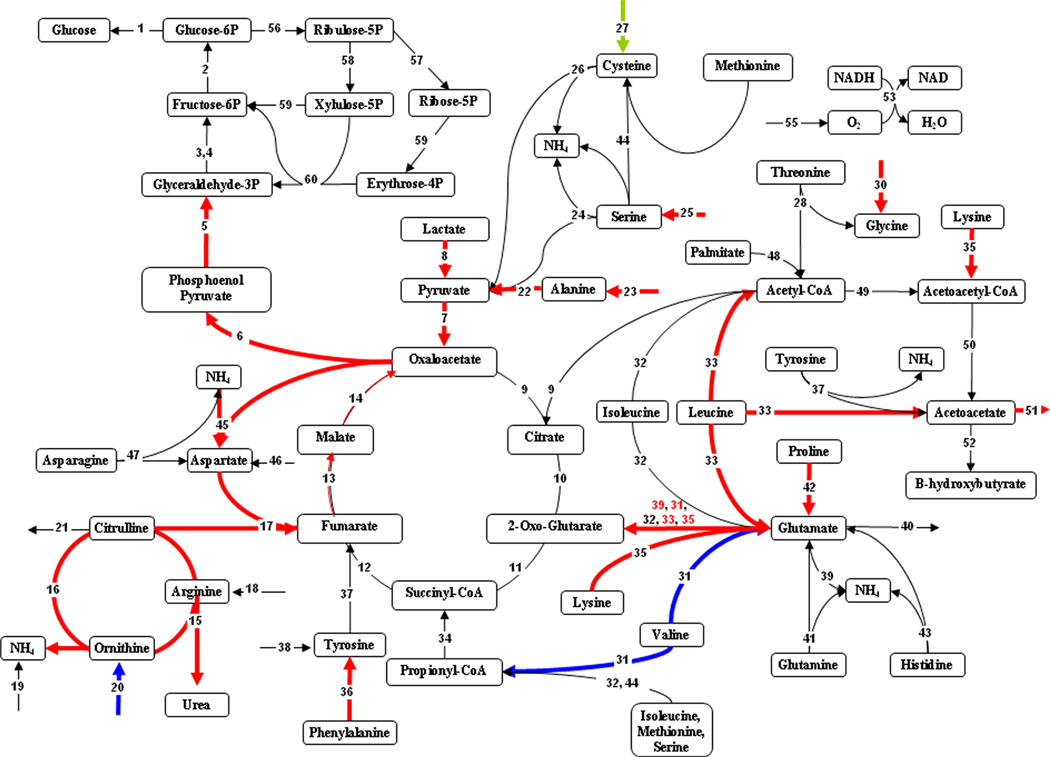

Figure 4.

Comparison of 40–20% TBSA burn on hepatic metabolic fluxes. Highlighted fluxes reflect differences in 40% TBSA burn results compared to 20% TBSA (black). Fluxes in red are up-regulated, those in blue are down-regulated, and fluxes in green are reversed. Thick lines show changes that are significant at a level of P < 0.05. Thin lines show changes that are significant at a level of P < 0.1.

Results

To determine the effect of burn injury on hepatic metabolism, rats were subjected to a dorsal burn covering 20% of the TBSA, or a combined dorsal and ventral burn covering 40% TBSA. Three days after burn, the animals were fasted overnight, and on the fourth day, PV and HA flow rates were measured and blood samples were taken. Sham controls consisted of rats that underwent the same procedures, but no burn injury.

Metabolite Concentrations

Table I displays the group averages of the measured extracellular metabolite concentrations in the PV, HA, and SHVC, which reflects the hepatic vein levels, in addition to the flow rates and liver weights. Additional relevant blood chemistry values not used specifically for MFA are represented in Table II.

There were no elevations in liver enzymes (ALT, AST, and ALP in Table II) or total bilirubin amongst any of the vessels in all groups, suggesting that no significant liver damage occurred within 4 days of burn injury. Plasma creatinine (Table II) and urea nitrogen (Table I) values remained within normal range for all rats suggesting unimpaired renal function due to burn injury. Blood flow rates showed a trend toward an increase in the PV and SHVC in the burn groups, and there was a ~30% reduction in HA flow rate in the 20% TBSA group. Overall values ranged between 1.7 and 2.2 mL/min/g liver in the PV and 0.07–0.05 mL/min/g liver in the HA for a cumulative inflow of 1.7–2.3 mL/min/g liver.

With respect to O2 and CO2 transport related parameters (Table I), a decrease in all three vessels (PV, HA, and SHVC) was observed in the 40% TBSA burn for total hemoglobin, along with a significant decrease in the HA and SHVC (although not in the PV) total O2 content. There was a significantly increased CO2 concentration in this group as well, and a 4-fold increase in lactate levels, in all vessels. As these trends were similar for all vessels, these changes are more likely representative of systemic effects of burn injury, and not due to specific hepatic functional differences. In the 20% TBSA burn, most of these changes were not seen and the majority of these parameters were similar to sham controls.

With respect to glucose, no significant change was observed, although a trend toward a decrease with increasing burn size was observed in the SHVC (Table I). Several of the lipid-related parameters, especially acetoacetic acid (Table I), VLDL, and triacylglycerol (Table II) were decreased. Acetoacetic acid (Table I) was significantly decreased in the SHVC and HA of the 40% TBSA group. The other ketone body, β-hydroxybutyric acid (Table I), exhibited a trend toward a decrease, although not statistically significant. VLDL and triacylglycerol (Table II) were significantly decreased in both 20% and 40% TBSA burn groups. In contrast, there was a trend toward an increase, and in some cases a significant increase, in LDL and cholesterol (Table II) in the PV and SHVC.

With respect to nitrogen and protein metabolism, albumin concentration was significantly decreased in all vessels in both burn groups (Table I), although there was no further decrease in albumin when going from 20% to 40% TBSA burn. Free ammonia levels decreased in general with increasing burn size, most evidently in the HA, but also in the SHVC (Table I). A general appreciation of amino acid metabolism was obtained by adding up the total amino acid nitrogen available in each vessel for each group, which is listed at the bottom of Table I. Total amino acid nitrogen in the PV and HA were within 10% of each other, while SHVC levels were 20–25% lower, indicating a net uptake of amino acids by the liver. Total amino acid nitrogen in any particular vessel did not vary much among experimental groups. The most change was seen in the PV, where the amino acid nitrogen content increased by ~10% in the 40% TBSA group compared to the sham control. Thus, there was a slight increase in the influx of amino acid nitrogen from the portal circulation in the larger burns.

More significant changes were observed for individual amino acids. The levels of eight amino acids, namely asparagine, glutamate, glutamine, glycine, proline, serine, methionine, and threonine, decreased in response to burns in the SHVC and HA, as well as PV (except for proline, methionine, and threonine). This decrease was largely compensated for by a concomitant increase in arginine (as much as 3-fold in the SHVC), which bears four nitrogens per molecule. The closely related (via the urea cycle) ornithine was also increased in the 40% TBSA group. Cysteine was elevated in the SHVC and HA, but not the PV, although it was a small contributor to the total amino acid nitrogen content due to its relatively low concentration.

Metabolic Flux Analysis

Net rates of uptake or release were calculated for a total of 28 metabolites from the measured concentrations and flow rates in the three vessels (PV, HA, and SHVC). These “measured” fluxes were normalized to the liver weights from each rat (Table III). These data were used as input to the MFA model to estimate the other, unmeasured, internal metabolic fluxes (Table IV).

Focusing on the measured fluxes first, we noted that O2 uptake and CO2 output were remarkably similar in the 20% TBSA burn compared to the sham control. In the 40% TBSA burn, O2 uptake and CO2 output were increased by ~60% and ~50%, respectively. Glucose output decreased while there was a net release of lactate in the 20% TBSA burn. In contrast, in the 40% TBSA burn, there was no change in glucose output, but a significant increase in lactate uptake. The 20% TBSA burn group showed no change in the ketone body (acetoacetate and β-hydroxybutyrate), urea or ammonia rates. The 40% TBSA burn group showed no change in the ketone body or ammonia rates, but a 2.7-fold increase in urea output compared to the sham.

With respect to amino acids, there were more changes in the 40% TBSA than the 20% TBSA burn group. Interestingly, many of the amino acids that had normal to decreased levels in the circulation showed a different response to burns in terms of fluxes. Alanine, glycine, proline, serine, asparagine, aspartate, glutamine, glutamate, and threonine all had normal to decreased levels according to Table I. The uptake of alanine, glycine, serine, and threonine was not significantly increased (although a trend was visible) with 20% TBSA burn, but significantly increased (except for threonine) with the 40% TBSA burn. Proline uptake was increased 7- to 10-fold in both burn groups compared to sham controls. These results suggest increased extraction of these particular amino acids by the liver in the larger burn group. In contrast, asparagine and aspartate significantly decreased their uptake with 20% TBSA burn, and did not change (compared to sham controls) with 40% TBSA burn. Finally, glutamine and glutamate rates were not significantly affected by burn injury. Phenylalanine and lysine, whose concentrations were elevated in the PV, correlated with significantly increased uptake rates.

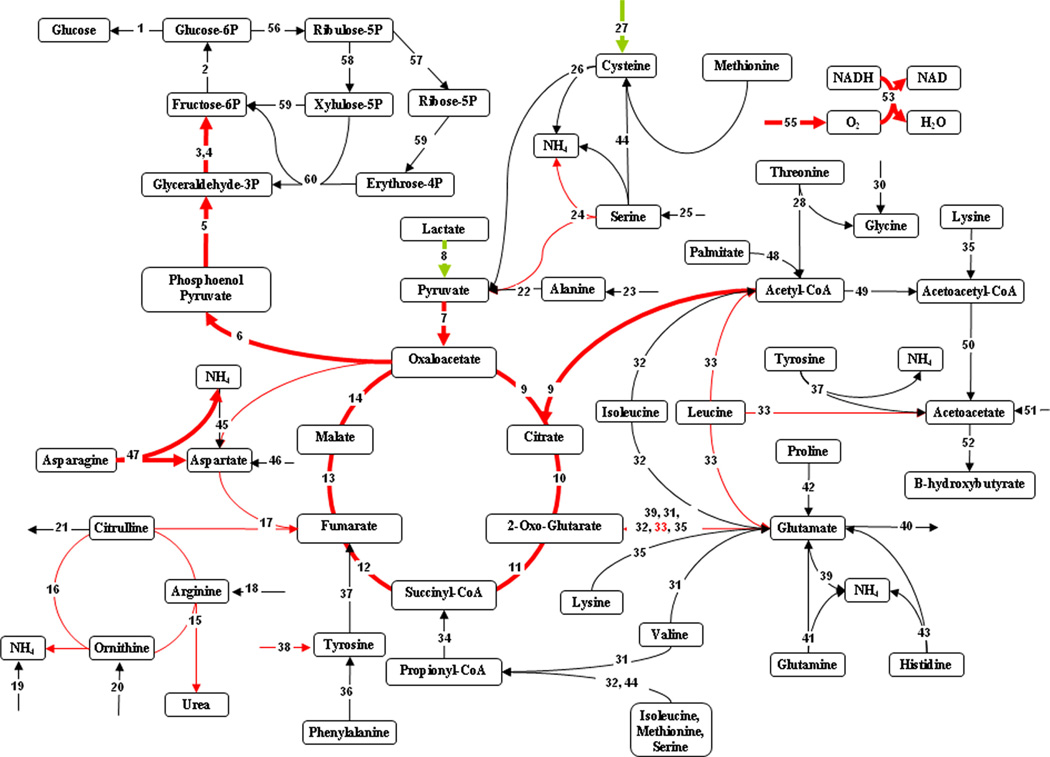

Results from MFA, which include both measured and estimated fluxes, are tabulated in Table IV, and also shown in Figures 1–4. Figure 1 represents cumulatively how fluxes in each major pathway were altered (amino acid metabolism, gluconeogenesis, TCA cycle, lipid metabolism, oxidative phosphorylation, and urea cycle). The results show a statistically significant reduction in gluconeogenesis in the 20% TBSA burn in contrast to a significant increase in 40% TBSA burn group. Trends for increased amino acid fluxes and reduced lipid fluxes were seen after burn injury. In all other circumstances, the 40% TBSA burn group had increased fluxes compared to the 20% TBSA group, which approximated the sham group. Only the PPP suggested an increase in the 20% burn compared to the 40% burn and sham.

Figure 1.

Summary of the effects of burn injury on the major pathways in the hepatic metabolic network. Values shown are the averages of all fluxes in each pathway group, which were then normalized to the sham group. Pathways (from Table IV) are grouped as follows: Gluconeogenesis: Fluxes #1–7, lactate metabolism and TCA cycle: Fluxes #8–14, oxidative phosphorylation: Fluxes #53–55, 61. Pentose phosphate pathway: Fluxes #56–60. Amino acid metabolism: Fluxes #18, 21–47, urea cycle: Fluxes #15–17, 19–20, lipid metabolism: Fluxes #48–52. *Significantly different from sham-burn group (P < 0.05). †Significantly different from 20% TBSA burn group (P < 0.05).

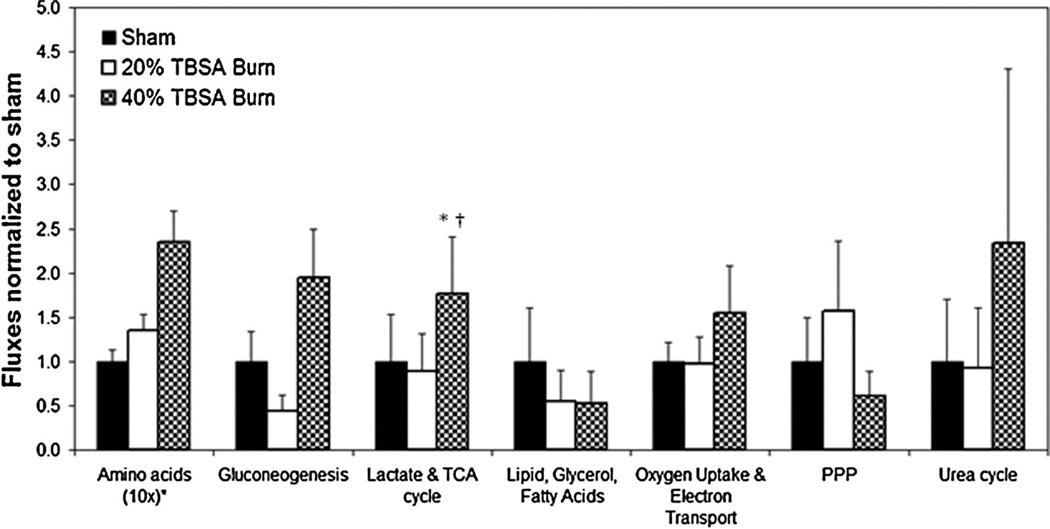

The metabolic flux distributions are depicted as comparisons of the 20% TBSA and 40% TBSA burn groups to the sham controls in Figures 2 and 3, respectively. The 20% TBSA burn group demonstrated few significant changes (Fig. 2), the most prominent being a reduction in fluxes throughout gluconeogenesis. We also observed that the flux of lactate to pyruvate was reversed, leading to net production of lactate. Measured amino acid flux changes that were mentioned in Table III are reflected in Figure 2 as well, most notably the hydrolysis of asparagine to aspartate and ammonia, which was significantly reduced; however, no related internal fluxes were significantly affected. By contrast to the 20% TBSA burn group, the 40% TBSA burn group showed a significant increase in the early steps of gluconeogenesis (Fig. 3). Lactate conversion to pyruvate was significantly increased, as was the uptake of several gluconeogenic amino acids. In addition, increased uptake of the ketogenic amino acids lysine and leucine occurred, which appeared to feed into the glutamate pool, and in turn α-ketoglutarate in the TCA cycle. This also led to increased acetyl-CoA and acetoacetate production. The urea cycle fluxes, as well as the fluxes connecting it to the TCA cycle were all significantly up-regulated.

Figure 3.

Effect of 40% TBSA burn injury on hepatic metabolic fluxes compared to sham controls. Highlighted fluxes reflect differences in 40% TBSA burn results compared to sham (black). Fluxes in red are up-regulated, those in blue are down-regulated, and fluxes in green are reversed. Thick lines show changes that are significant at a level of P < 0.05. Thin lines show changes that are significant at a level of P < 0.1.

Figure 4 illustrates the differences in hepatic metabolism between the 20% and 40% TBSA burn models. Fluxes around the TCA cycle and electron transport chain were significantly increased in the larger burn, suggesting increased energy production. In addition, there was a clear induction of the route from lactate to pyruvate and the gluconeogenic pathway. The urea cycle fluxes were also up-regulated in the larger burn.

Discussion

We investigated the effect of cutaneous burn injuries of different severity on the hepatic metabolic response in a rat model. More specifically, we combined measurements of metabolite concentrations and flow rates in the major vessels entering and leaving the liver, as well as a mass balance model, to generate a quantitative picture of the metabolic state of liver in sham, 20% TBSA and 40% TBSA burned rats. The main findings were: (1) Sham-burned animals exhibited a gluconeogenic pattern, consistent with the fasted state; (2) the small (20% TBSA) burn inhibited gluconeogenesis and exhibited glycolytic-like features with very few other significant changes; (3) the large (40% TBSA) burn, in contrast, further enhanced gluconeogenesis and also increased amino acid extraction, urea cycle reactions, and several reactions involved in oxidative phosphorylation. These results suggest that increasing the severity of injury (in our model, the TBSA of the burn) does not lead to a simple dose-dependent metabolic response, but rather leads to qualitatively different responses. This suggests that the metabolic response may shift when the severity of burns—in our case increasing the burn area from 20% to 40% TBSA by adding the ventral burn, reaches a certain threshold. Alternatively, there could be qualitative differences between similar area ventral versus dorsal burns. Interestingly, to the best of our knowledge, the latter issue has never been explored in the published literature.

The observed metabolic changes occurred in the absence of any frank organ damage, as suggested by the normal levels of ALT, AST, and ALP (typically used as indices of liver damage), as well as creatinine and urea nitrogen (indices of renal damage). Hepatic blood flow rates were similar to literature values, such as that reported by Daemen et al. (1989), with a total inflow of ~1.7 mL/min/g. Furthermore, prior data suggested that burn injury may increase portal flow and decrease arterial flow for an ultimately insignificant increase in total hepatic blood flow (Carter et al., 1988), in agreement with our findings. The decrease in albumin levels in both burn groups is consistent with the induction of a systemic inflammatory response in these animals since albumin is a negative acute phase protein, and decreased circulating albumin is commonly seen in burn injury (Don and Kaysen, 2004).

Oxygenation parameters in the small burn group were very close to the sham, while they were significantly altered in the large burn group (Table I). In the latter, the oxygen uptake and CO2 production rates were increased by 50–60% compared to the sham and/or small burn. This increase is qualitatively in agreement with prior data from liver perfusion studies (Lee et al., 2000, 2003; Yamaguchi et al., 1997), and suggest that the liver may contribute a significant portion of the increased whole-body energy expenditure that has been reported in burn patients (Jeschke et al., 2000, 2007). It is noteworthy that in the large burn group, there was a ~4-fold increase in circulating lactate levels, a decrease in SHVC and HA O2 content, and an increase in CO2 in all vessels. Since our measurements show net hepatic lactate uptake in this group, the accumulation of lactate must have been from increased anaerobic glycolysis in non-hepatic tissues, which could reflect some level of ischemia. The systemic increase in CO2/O2 ratio may indicate insufficient gas exchange in the lungs in the face of increased O2 uptake and CO2 generation by the liver (Table III) and possibly other tissues. This could be partly attributed to the decrease in hemoglobin content that we also observed in this group (Table I).

The small and large burn groups exhibited distinctly different responses in gluconeogenesis. Since all animals were fasted, we did not expect a glycolytic pattern to emerge; however, the small burn group did show a reversal of the lactate to pyruvate flux to a net production of lactate along with significant reductions in several fluxes of the gluconeogenic pathway including net glucose output (Fig. 2). More specifically, oxaloacetate flux, the conduit to forming phosphoenolpyruvate (Flux #6) was half the value of the sham control. Oxaloacetate flux from pyruvate occurred at a tenth of the rate in sham. Oxaloacetate formation from malate occurred at the normal rate (Flux #14), but was largely shunted into the production of aspartate (Flux #45), thereby likely explaining the reduction in asparagine uptake in this group. Lactate levels were slightly decreased in the small burn group (Table I), in addition to the fact that the levels of insulin, a proglycolytic hormone in the liver, were elevated 3.5-fold compared to sham (Table II). Both of these factors could have contributed to the switch from lactate consumption to net release in the small burn group. In contrast, gluconeogenic fluxes, including lactate utilization, and conversion to pyruvate were significantly elevated in the large burn (Fig. 2). Because of the 4-fold increased lactate levels in the large burn group, we cannot exclude a possible mass action effect driving the reaction from lactate to pyruvate. Interestingly, insulin levels in the large burn group were even higher than the small burn (Table II), but none of the flux patterns reflected glycolysis. Further analysis would be required to determine whether this could be the result of “insulin resistance” (Cree and Wolfe, 2008) and/or the effect of other pro-gluconeogenic hormones (such as glucagon and corticosterone) typically released after severe injury.

Another important finding is that burn injury increased the utilization of specific amino acids. The effect was limited to alanine, proline, and phenylalanine in the small burn model (Fig. 2), but more generalized in the larger burn model, involving the same amino acids, and also serine, glycine, lysine, and leucine. Among these amino acids, the levels of alanine, glycine, proline, and serine were significantly reduced in the SHVC and HA, and unchanged to reduced in the PV (Table I). Taken together, these results suggest that the liver was more actively extracting these amino acids from the circulation in the burn groups. Consistent with this notion, a prior study reported that 20% and 40% TBSA burns in rats cause dose-dependent increases in the activity of the hepatic amino acid transporter system A (Lohmann et al., 1998), which is one of the major cellular transport mechanisms of alanine and other neutral amino acids.

Among all amino acids, alanine uptake rate was the largest (Table II), followed by histidine, and glycine. Alanine is well-documented as a major source for gluconeogenesis in critically ill patients (Wilmore et al., 1980). Interestingly glutamine utilization was not significantly affected by burns in our rat model, while it is usually considered to be a major source of nitrogen in humans. Karner et al. (1984) suggested that glycine may replace the role of glutamine in rats, and we did see a significant increase in glycine ultilization in the large burn group. Proline utilization was relatively small in the sham group, but increased by 7- to 10-fold in the burn groups, becoming a significant contributor of the total amino acid uptake by the liver (Table II). Proline, along with lysine and leucine in the case of the large burn, appeared to feed into the glutamate pool, which in turned fed into α-ketoglutarate in the TCA cycle.

We compared our in vivo hepatic hypermetabolic response from a 20% TBSA burn injury to previously published results that evaluated the same burn model using ex vivo organ perfusion (Banta et al., 2005). The results demonstrated some commonalities in metabolite pools such as a decrease in pyruvate and an increase in glutamate compared to sham, but the fluxes contributing to these pools were dissimilar. Further, there were significant differences in amino acid utilization, and gluconeogenesis. Some of these differences can be explained by compositional variations in perfusate and blood. In particular, insulin was not included in the perfusates, which caused the reduction in gluconeogenesis seen in vivo. However, many of the differences could not be attributed to substrate concentrations. These included such findings as the elevated lactate production in vivo despite having higher concentrations than in perfusate, or increased phenylalanine, proline, and alanine uptake in vivo, despite lower concentrations than in perfusate. Together these results suggest that ex vivo organ perfusion systemically impacts hepatic metabolism and is a significant consideration when evaluating disease processes using this technique. Ex vivo perfusions are best suited to investigating the impact of specific factors in perfusate and differentiating intrinsic metabolic outcomes unaffected by short-term changes in hormone and substrate loads. Ex vivo perfusions offer the advantage of noise minimization where substrate load and hormonal composition can be carefully controlled at the cost of clinically relevant data caused by placing the liver in a nonphysiological environment.

From a methods perspective, the in situ sampling technique used in this study revealed the intrinsic function of the liver in response to normal or pathological conditions, deduced by accounting for the extrinsic hormonal and substrate variations that impacted liver metabolism. Metabolite concentrations on the order of a tenth of a µmol/g liver resulted in very small arterio-venous differences and consequently noisy fluxes. A more significant drawback of the technique was its terminal invasiveness, with each animal providing data for a single time point. However, compared to whole body tracer experiments, the main advantage of in situ measurements was obtaining a physiological and comprehensive metabolic map of the liver. Further, the raw data obtained is independent of the simplifying assumptions made in the MFA model and can always be used in new and improved models. By contrast, labeling techniques focus on a specific metabolic pathway and different labels are needed if other pathways are to be investigated. Typically, simplifying assumptions must also be made here in order to convert the isotopic dilution data into meaningful flux data. In principle, these assumptions must be validated for every disease or injury model to be studied. Nevertheless, some of these techniques have been found extremely reliable for estimating certain internal fluxes, and are generally better established than MFA.

In summary, we have performed the first in situ MFA of the liver to characterize the hepatic metabolic response to experimental burn injury. We found that after 4 days post-burn significantly different metabolic changes in the liver result depending on burn severity. In a small rat burn injury (20% TBSA) model, the response was mild and showed a glycolytic pattern. In a large burn injury (40% TBSA) model, widespread changes were observed aimed at increasing gluconeogenesis and amino acid utilization. These results suggest that increasing the severity of injury (in our model, the TBSA of the burn) does not lead to a simple dose-dependent metabolic response, but rather leads to qualitatively different responses. This finding, if extended to human burn patients, suggest that different nutritional and hormonal approaches may be required depending on the severity of injury.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Shriners Hospitals for Children (8640, 8450, 8460, 8490, 8496, and 8503) and the National Institutes of Health grant # DK080942.

Footnotes

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article.

References

- Arai K, Lee K, Berthiaume F, Tompkins RG, Yarmush ML. Intrahepatic amino acid and glucose metabolism in a D-galactosamine-induced rat liver failure model. Hepatology. 2001;34:360–371. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.26515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atiyeh BS, Gunn SW, Dibo SA. Metabolic implications of severe burn injuries and their management: A systematic review of the literature. World J Surg. 2008;32(8):1857–1869. doi: 10.1007/s00268-008-9587-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banta S, Vemula M, Yokoyama T, Jayaraman A, Berthiaume F, Yarmush ML. Contribution of gene expression to metabolic fluxes in hypermetabolic livers induced through burn injury and cecal ligation and puncture in rats. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2007;97(1):118–137. doi: 10.1002/bit.21200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banta S, Yokoyama T, Berthiaume F, Yarmush ML. Effects of dehydroepiandrosterone administration on rat hepatic metabolism following thermal injury. J Surg Res. 2005;127(2):93–105. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2005.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baskaran H, Yarmush ML, Berthiaume F. Dynamics of tissue neutrophil sequestration after cutaneous burns in rats. J Surg Res. 2000;93:88–96. doi: 10.1006/jsre.2000.5955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosaeus I. Nutritional support in multimodal therapy for cancer cachexia. Support Care Cancer. 2008;16(5):447–451. doi: 10.1007/s00520-007-0388-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabral CB, Bullock KH, Bischoff DJ, Tompkins RG, Yu YM, Kelleher JK. Estimating glutathione synthesis with deuterated water: A model for peptide biosynthesis. Anal Biochem. 2008;379(1):40–44. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2008.04.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter EA, Burks D, Fishcman AJ, White M, Tompkins RG. Insulin resistance in thermally-inured rats is associated with post-receptor alterations in skeletal muscle, liver and adipose tissue. Int J Mol Med. 2004;14:653–658. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter EA, Tompkins RG, Burke JF. Hepatic and intestinal blood flow following thermal injury. J Burn Care Rehabil. 1988;9(4):347–350. doi: 10.1097/00004630-198807000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CL, Fei Z, Carter EA, Lu XM, Hu RH, Young VR, Tompkins RG, Yu YM. Metabolic fate of extrahepatic arginine in liver after burn injury. Metabolism. 2003;52(10):1232–1239. doi: 10.1016/s0026-0495(03)00282-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cree MG, Wolfe RR. Postburn trauma insulin resistance and fat metabolism. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2008;294(1):E1–E9. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00562.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daemen MJAP, Thijssen HHW, van Essen H, Vervoort-Peters HTM, Prinzen FW, Struyker Boudier HAJ, Smits JFM. Liver blood flow measurement in the rat. J Pharmacol Methods. 1989;21:287–297. doi: 10.1016/0160-5402(89)90066-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Don BR, Kaysen G. Serum albumin: Relationship to inflammation and nutrition. Semin Dial. 2004;17(6):432–437. doi: 10.1111/j.0894-0959.2004.17603.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein SA, Elwyn DH. The effects of injury and sepsis on fuel utilization. Annu Rev Nutr. 1989;9:445–473. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nu.09.070189.002305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart DW, Wolf SE, Herndon DN, Chinkes DL, Lal SO, Obeng MK, Beauford RB, Mlcak RR. Energy expenditure and caloric balance after burn: Increased feeding leads to fat rather than lean mass accretion. Ann Surg. 2002;235(1):152–161. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200201000-00020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herndon DN, Tompkins RG. Support of the metabolic response to burn injury. Lancet. 2004;363(9424):1895–1902. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16360-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izamis ML, Uygun K, Uygun B, Yarmush ML, Berthiaume F. Effects of burn injury on markers of hypermetabolism in rats. J Burn Care Res. 2009;30(6):993–1001. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0b013e3181bfb7b4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeschke M, Herndon D, Barrow R. Insulin-like growth factor I in combination with insulin-like growth factor binding protein 3 affects the hepatic acute phase response and hepatic morphology in thermally injured rats. Ann Surg. 2000;231(3):408–416. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200003000-00014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeschke MG, Chinkes DL, Finnerty CC, Kulp G, Suman OE, Norbury WB, Branski LK, Gauglitz GG, Mlcak RP, Herndon DN. Pathophysiologic response to severe burn injury. Ann Surg. 2008;248(3):387–401. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181856241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeschke MG, Mlcak RP, Finnerty CC, Norbury WB, Gauglitz GG, Kulp GA, Herndon DN. Burn size determines the inflammatory and hypermetabolic response. Crit Care. 2007;11(4):R90. doi: 10.1186/cc6102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karner J, Roth E, Funovics J, Hanusch J, Walzer L, Adamiker D, Berger A, Meissl G. Effects of burns on amino acid levels in rat plasma, liver and muscle. Burns. 1984;11:130–137. doi: 10.1016/0305-4179(84)90136-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K, Berthiaume F, Stephanopoulos GN, Yarmush ML. Profiling of dynamic changes in hypermetabolic livers. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2003;83(4):400–415. doi: 10.1002/bit.10682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K, Berthiaume F, Stephanopoulos GN, Yarmush DM, Yarmush ML. Metabolic flux analysis of postburn hepatic hypermetabolism. Metab Eng. 2000;2:312–327. doi: 10.1006/mben.2000.0160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohmann R, Souba W, Zakrzewski K, Bode B. Stimulation of rat hepatic amino acid transport by burn injury. Metabolism. 1998;47(5):608–616. doi: 10.1016/s0026-0495(98)90248-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagrath D, Avila-Elchiver M, Berthiaume F, Tilles AW, Messac A, Yarmush ML. Integrated energy and flux balance based multiobjective framework for large-scale metabolic networks. Ann Biomed Eng. 2007;35(6):863–885. doi: 10.1007/s10439-007-9283-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira CT, Herndon DN. The pharmacologic modulation of the hypermetabolic response to burns. Adv Surg. 2005;39:245–261. doi: 10.1016/j.yasu.2005.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schols AM. Pulmonary cachexia. Int J Cardiol. 2002;85(1):101–110. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5273(02)00238-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwenk A, Kremer G, Cornely O, Diehl V, Fatkenheuer G, Salzberger B. Body weight changes with protease inhibitor treatment in undernourished HIV-infected patients. Nutrition. 1999;15(6):453–457. doi: 10.1016/s0899-9007(99)00083-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwenk A, Macallan DC. Tuberculosis, malnutrition and wasting. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2000;3(4):285–291. doi: 10.1097/00075197-200007000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker HL, Mason AD. A standard animal burn. J Trauma. 1968;8(6):1049–1051. doi: 10.1097/00005373-196811000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang NS, Stephanopoulos G. Application of macroscopic balances to the identification of gross measurement errors. Biotechnol Bioeng. 1983;25(9):2177–2208. doi: 10.1002/bit.260250906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilmore DW, Goodwin CW, Aulick LH, Powanda MC, Mason AD, Pruitt BA. Effect of injury and infection on visceral metabolism and circulation. Ann Surg. 1980;192(4):491–504. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198010000-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witten IH, Frank E. Data mining: Practical machine learning tools and techniques: Morgan Kaufmann. San Francisco: Morgan Kaufmann; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi Y, Yu YM, Zupke C, Yarmush DM, Berthiaume F, Tompkins RG, Yarmush ML. Effect of burn injury on glucose and nitrogen metabolism in the liver: Preliminary studies in a perfuse liver system. Surgery. 1997:121. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6060(97)90358-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L, Kasumov T, Kombu RS, Zhu SH, Cendrowski AV, David F, Anderson VE, Kelleher JK, Brunengraber H. Metabolomic and mass isotopomer analysis of liver gluconeogenesis and citric acid cycle: II. Heterogeneity of metabolite labeling pattern. J Biol Chem. 2008a;283(32):21988–21996. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M803455200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L, Kombu RS, Kasumov T, Zhu SH, Cendrowski AV, David F, Anderson VE, Kelleher JK, Brunengraber H. Metabolomic and mass isotopomer analysis of liver gluconeogenesis and citric acid cycle. I. Interrelation between gluconeogenesis and cataplerosis; formation of methoxamates from aminooxyacetate and ketoacids. J Biol Chem. 2008b;283(32):21978–21987. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M803454200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yarmush DM, MacDonald AD, Foy BD, Berthiaume F, Tompkins RG, Yarmush ML. Cutaneous burn injury alters relative tricarboxylic acid cycle fluxes in rat liver. J Burn Care Rehabil. 1999;20(4):292–302. doi: 10.1097/00004630-199907000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokoyama T, Banta S, Berthiaume F, Nagrath D, Tompkins RG, Yarmush ML. Evolution of intrahepatic carbon, nitrogen, and energy metabolism in a D-galactosamine-induced rat liver failure model. Metab Eng. 2005;7(2):88–103. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2004.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhaofan X, Jianguang T, Guangyi W, Hongtai T, Shengde G, Horton JW. Effect of thermal injury on relative anaplerosis and gluconeogenesis in the rat during infusion of [U-13C] propionate. Burns. 2002;28(7):625–630. doi: 10.1016/s0305-4179(02)00098-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.