Abstract

Background

The calcium-binding proteins myeloid-related protein (MRP)-8 (S100A8) and MRP-14 (S100A9) form MRP-8/14 heterodimers (S100A8/A9, calprotectin) that regulate myeloid cell function and inflammatory responses, and serve as early serum markers for monitoring acute allograft rejection. Despite functioning as a pro-inflammatory mediator, the pathophysiological role of MRP-8/14 complexes in cardiovascular disease is incompletely defined. This study investigated the role of MRP-8/14 in cardiac allograft rejection using MRP-14-deficient mice (MRP14-/-) that lack MRP-8/14 complexes.

Methods and Results

We examined parenchymal rejection (PR) after major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II allomismatched cardiac transplantation (bm12 donor heart and B6 recipients) in wild-type (WT) and MRP14-/- recipients. Allograft survival averaged 5.9 ± 2.9 weeks (n=10) in MRP14-/- recipients, compared to > 12 weeks (n = 15, p < 0.0001) in WT recipients. Two weeks after transplantation, allografts in MRP14-/- recipients had significantly higher PR scores (2.8 ± 0.8, n=8) than did WT recipients (0.8 ± 0.8, n=12, p<0.0001). Compared to WT recipients, allografts in MRP14-/- recipients had significantly increased T-cell and macrophage infiltration, as well as increased mRNA levels of IFN-γ and IFN-γ–associated chemokines (CXCL9, CXCL10, and CXCL11), IL-6, and IL-17, with significantly higher levels of Th17 cells. MRP14-/- recipients also had significantly more lymphocytes in the adjacent paraaortic lymph nodes than did WT recipients (cell number per lymph node: 23.7 ± 0.7 × 105 for MRP14-/- vs. 6.0 ± 0.2 × 105 for WT, p < 0.0001). The dendritic cells (DCs) of the MRP14-/- recipients of bm12 hearts expressed significantly higher levels of the co-stimulatory molecules CD80 and CD86 than did those of WT recipients 2 weeks after transplantation. Mixed leukocyte reactions using allo-EC-primed MRP14-/- DCs resulted in significantly higher antigen-presenting function than reactions using WT DCs. Ovalbumin-primed MRP14-/- DCs augmented proliferation of OT-II CD4+ T cells with increased IL-2 and IFN-γ production. Cardiac allografts of B6 MHC class II-/- hosts and of B6 WT hosts receiving MRP14-/- DCs had significantly augmented inflammatory cell infiltration and accelerated allograft rejection, compared to WT DCs from transferred recipient allografts. Bone marrow–derived MRP14-/- DCs infected with MRP-8 and MRP-14 retroviral vectors showed significantly decreased CD80 and CD86 expression compared to controls, indicating that MRP-8/14 regulates B7-costimulatory molecule expression.

Conclusion

Our results indicate that MRP-14 regulates B7 molecule expression and reduces antigen presentation by DCs, and subsequent T-cell priming. The absence of MRP-14 markedly increased T-cell activation and exacerbated allograft rejection, indicating a previously unrecognized role for MRP-14 in immune cell biology.

Keywords: MRP-8 (S100A8), MRP-14 (S100A9), T-lymphocytes, macrophages, dendritic cells, antigen-presenting cells, cytokine, heart transplantation, pathogenesis

Introduction

The calcium-binding proteins MRP-8 (S100A8, calgranulin A) and MRP-14 (S100A9, calgranulin B) belong to the S100 protein family. MRP-14 and MRP-8 form homodimers, heterodimers, and higher-order complexes, although the MRP-8/14 heterodimer (S100A8/A9, calprotectin) is the dominant extracellular form in humans.1, 2 MRP-8/14 heterodimers constitute ∼45% of human neutrophil, ∼1% of human monocyte, and 10∼20% of murine neutrophil cytosolic proteins.1, 3-5 Myeloid cells such as neutrophils, monocytes, and dendritic cells (DCs), along with activated macrophages, platelets, and megakaryocytes, express MRP-8 and MRP-14, while most non-activated macrophages, T cells, and B cells do not express them.3, 6-8

MRP-8/14 heterodimers translocate from cytoplasm to the cytoskeleton and membranes of phagocytes upon elevation of intracellular calcium concentration,9 and secreted extracellular MRP-8/14 enhances CD11b/CD18 integrin-binding activity on phagocytes,10, 11 promoting transendothelial migration of phagocytes. Vascular endothelium expresses several classes of MRP-8/14 receptors, including toll-like receptor-4 (TLR-4),12 receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE),13 CD36,14 special carboxylated N-glycans,15 and heparin-like glycoaminoglycans.16

MRP-8/14 complexes also contribute to wound repair,17 have antiproliferative effects on monocytes/macrophages and lymphocytes,18, 19 and inhibit the growth of fibroblasts.20 MRP-8/14 complexes may participate in the pathogenesis of cardiovascular disease and allograft rejection.8, 21 MRP-8/14-expressing macrophages appear during the early phase of cardiac allograft rejection.22 MRP-8/14 is a very early serum marker of acute rejection, with high sensitivity (67%) and specificity (100%).23 In a study of 56 patients with acute renal allograft rejection, elevated MRP-8/14 serum levels preceded acute rejection episodes by a median of 5 days, and a 3-day course of intravenous methylprednisolone therapy significantly reduced MRP-8/MRP-14 serum levels.

Conversely, previous work in transplantation showed that a subpopulation of monocytes lacking MRP-8/14 expression associate with chronic allograft rejection.24 Moreover, human renal allograft recipients without allograft vascular disease had significantly higher MRP-8/14 levels shortly after transplantation, compared to lower levels in those recipients that developed vascular disease. Thus, MRP-8/14 has uncertain roles in transplantation biology.

This study investigated the role of MRP-14 in cardiac allograft rejection using MRP-14-deficient mice (MRP14-/-) lacking MRP-8/14 complexes.25, 26 The results show that host MRP-14 deficiency augmented antigen presentation by DCs, markedly increased T-cell activation, and exacerbated allograft rejection.

Methods

Animals

C57BL/6 (B6; H-2b, I-Ab), B6.C-H2<bm12>KhEg (bm12; H-2bm12, I-Ab), B6.129S7-Rag1tm1Mom Tg (TcraTcrb) 425Cbn (Rag1 knockout/ OT-II T cell receptor transgenic, H-2b), and BALB/c (B/c, H-2d, I-Ad) mice were obtained from Taconic Farm (Hudson, NY) or the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). MRP14-/- mice were generated using GK129 embryonic stem (ES) cells and backcrossed 12 times on the B6 background, as described previously.25 Mice were maintained on acidified water in barrier animal facilities. Animal care and procedures were reviewed and approved by the Harvard Medical School Standing Committee on Animals, and performed in accordance with the guidelines of the American Association for Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care and the National Institutes of Health.

Vascularized heterotopic cardiac transplantation

B/c (total allo-mismatch) or bm12 (MHC class II-mismatch) donor hearts were transplanted heterotopically into B6 recipients without immunosuppression, as shown previously (details in Supplemental Methods).27

Because minor histoincompatibility can influence allo-immune responses significantly, we examined inflammatory responses in B6 WT cardiac allografts in MRP14-/- recipients. We did not detect any inflammatory cell accumulation in the B6 WT cardiac allografts in MRP14-/- recipients 4 weeks after transplantation (Supplemental Figure S1), indicating that variation in genetic background between WT and MRP14-/- mice does not account for differences in the cardiac transplantation assays.

Graft harvest

Harvested allografts were transversely sectioned into three parts. In sectioned hearts, the most basal part was used for routine hematoxylin and eosin morphological examination. A second mid-transverse section was frozen for immunohistochemical staining, and the apical portion was used for total RNA extraction for measuring mRNA levels of cytokines and chemokines by quantitative real-time PCR.28 For cellular extraction, hearts were digested at 37°C in 2 mg/mL collagenase (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and 2% bovine serum albumin in buffered saline, followed by straining and Ficoll density gradient centrifugation (Organon Teknika, Durham, NC).27

Quantification of mRNA by real-time, quantitative RT-PCR

Messenger RNA (mRNA) levels of cytokines and chemokines were quantified from cardiac allografts harvested 2 weeks after transplantation, or from in vitro cultured marrow-derived DCs, using a LightCycler™-based real-time PCR. Quantitative RT-PCR protocols used the LightCycler™-DNA Master SYBR Green I kit, as described previously.29 Total RNA was extracted from cardiac allografts using Trizol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and purified with RNeasy kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA); cDNA was synthesized with a First-Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit followed by DNase treatment (Invitrogen). TaqStart™ antibody (CLONTECH, Palo Alto, CA) was used to prevent generation of nonspecific amplification products. Quantification was performed using primers designed by the Primer3 program (www.genome.wi.mit.edu/cgi-bin/primer/primer3_www.cgi). The mRNA levels of the various genes tested were normalized to GAPDH as an internal control. Data represent the mean ± SEM of six to seven determinations of the rates of mRNA expression relative to the control WT recipient allografts, which were set to one.

Mixed lymphocyte reaction (MLR), T-cell proliferation assay, and cytokine ELISA

One-way MLR was performed as described previously,28 using irradiated BALB/c splenocytes as stimulators and B6 splenocytes as responders. T-cell or B-cell proliferation assays were performed using anti-CD3 Ab-coated 96-well plates or by adding anti-CD40 mAbs (3/23, BD Pharmingen), respectively.28

We performed primed MLR by co-culturing B6 WT or B6 MRP-14-/- marrow-derived DCs with bm12-EC for 72 hours. EC were isolated from the bm12 murine hearts as described previously.28, 30 These DCs were then used as stimulators for naive B6 T-cell responders. T cells were extracted from naive B6 WT splenocytes using MACS beads (Miltenyi Biotec Inc., Auburn, CA) with negative selection, according to the manufacturer's instructions. We co-cultured irradiated allo-EC–primed DC (50,000 cells/well) and naive B6 T cells (500,000 cells/well, S:R=1:10) in 96-well plates and measured T-cell proliferation using 3H-thymidine incorporation.28 Non-primed DCs were used as negative controls.

Bone marrow-derived DC preparation for allo-EC–primed MLR and/or flow cytometry

Marrows from femurs and tibias from 8-to-12-week-old male B6 WT or B6 MRP-14-/- mice were flushed with RPMI-1640, using a syringe with a 27G needle. Clusters within the marrow suspension were dissociated by vigorous pipetting, and filtered through a 70-μm cell strainer. Erythrocytes were lysed with ACK lysing buffer (0.15 M NH4Cl, 1.0 mM KHCO3, 0.1 mM EDTA). Approximately 1-2×107 marrow cells were obtained per mouse. Bone marrow cells were suspended in complete media (C10, RPMI-1640) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 2 mM L-glutamine, 1% of nonessential amino acids, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin). All culture reagents were purchased from Life Technologies (Rockville, MD). 10 million cells in 5 ml of C10 were cultured in 6-cm dishes for up to 7 days in the presence of 1000 U/ml of GM-CSF and IL-4 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) at 37 °C, 5% CO2. On days 2 and 4 of culture, floating and loosely adherent cells were discarded, and 50% of the media was replaced with fresh media containing the same amount of cytokines. Monocytes cultured in this cytokine combination for this duration develop into immature DCs that characteristically bear high endocytic and macropinocytic activity and low expression of co-stimulatory signals.31 On day 7, these DCs were co-cultured with allo-ECs for 72 hours, to allow the DCs to process antigen and develop into mature DCs; DCs cultured without allo-ECs were used as negative controls. On day 10, CD11c+ DCs were recovered using anti-mouse CD11c Ab-bound magnetic beads (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA), according to the manufacturer's instructions. DCs were irradiated (3000 rad) and cultured at 5×104 cells/well in 96-well dishes with naive B6 T cells at 5×105 cells/well. For flow cytometry analysis, WT and MRP-14-/- DCs were first stimulated with 500 U/ml IFN-γ for 18 hours.

Cellular surface staining and flow cytometric analysis

IFN-γ-stimulated DCs were analyzed by flow cytometry after surface staining using methods described previously.27 Antibodies included anti-MHC II-PE (I-A/I-E, M5/114.15.2); anti-CD40-PE, CD86-PE, or ICOSL-PE antibodies; PE-conjugated rat IgG2b (negative control, Pharmingen); or anti-CD80-PE and PE-conjugated hamster IgG (negative control). APC-conjugated anti-CD11c antibody was used for DC staining.

Intracellular cytokine staining for flow cytometry

We performed intracellular cytokine staining and flow cytometry as described previously (details in Supplemental Methods).27

CFSE labeling of OT-II TCR transgenic CD4+ T cells and co-culture of OT-II CD4+ T cells and ovalbumin-primed DCs

We isolated CD4+ T cells from the spleen of OT-II TCR transgenic mice using the magnetic cell-sorting (MACS) system (Miltenyi Biotec Inc., Auburn, CA), following the manufacturer's instructions. We then labeled CD4+ T cells with the CFSE labeling kit (Invitrogen). Five million CFSE-labeled OT-II CD4+ T cells per well were co-cultured with bone marrow–derived B6 WT or MRP14-/- DC, in the presence of 10 μM ovalbumin in a 6-well plate. We collected supernatants for cytokine analysis by ELISA 2–4 days after T-cell plating, and harvested T cells and DCs for flow cytometry 4 days after T-cell plating. We also performed flow cytometry and defined T-cell proliferation by calculating the proliferation index — the percentages of the sum of the cells in all generations divided by the calculated number of original parent cells, as described previously.32

Isolation of lymphocytes from spleen and cardiac allograft

We isolated lymphocytes from spleen and cardiac allografts as described previously (details in Supplemental Methods).32

Construction of MRP-8/14 expression vectors and DC retrovirus infection

MRP-8 and MRP-14 cDNAs were cloned by PCR amplification and inserted into the mouse stem cell retrovirus-based internal ribosomal entry site–enhanced green fluorescent protein (IRES-2–EGFP) vectors, which use the viral endogenous promoter to direct the expression of the cloned cDNAs. The expression plasmids were transfected into the packaging cell line Phoenix using TransIT293 transfection reagent (Mirus Bio Corporation, Madison, WI) according to the manufacturer's instructions, and the supernatants were collected, filtered, and stored at -80°C. Typically, retrovirus titers after packaging were ∼1 × 107/ml. The mixture of viral supernatants was placed on the cultured DCs and centrifuged for 3 hours at 700 x g at room temperature. This step was repeated three times, and then media were replaced with 10% FCS DMEM and cultured for 24 hours before costimulatory molecule analysis. MRP-14-/- DCs infected with MRP-8 and MRP-14 retroviral vectors expressed MRP-8 and MRP-14 proteins, and MRP-14-/- DCs infected with control, MRP-8, and MRP-14 vectors showed enhanced GFP.

Statistical analysis of graft survival and cell number, proliferation, and cytokine production

Graft survival curves were estimated by the Kaplan-Meier method and compared between the two groups by the log-rank test. Comparisons between treatment groups on the frequency of graft-infiltrating cells, cell proliferation, ELISA, PR, and GAD scores used t-tests accounting for unequal variances when heterogeneity was present (when F test for equal variances yielded p <0.05). We used two-way ANOVA and the Bonferroni method for statistical analysis of the lymphocyte count in lymph nodes before and after transplant in a comparison of WT and MRP-14-/- recipients, and cytokine production levels in the supernatant of OT-II CD4+ T cells co-cultured with WT or MRP14-/- DCs in the presence or absence of ovalbumin. Two-tailed tests were used, with p < 0.05 considered statistically significant. We used GraphPad Prism 4 or Statview software for Macintosh for statistical analysis.

Results

Deficiency of recipient MRP-14 accelerates parenchymal rejection and exacerbates graft survival in MHC class II-allomismatched allografts

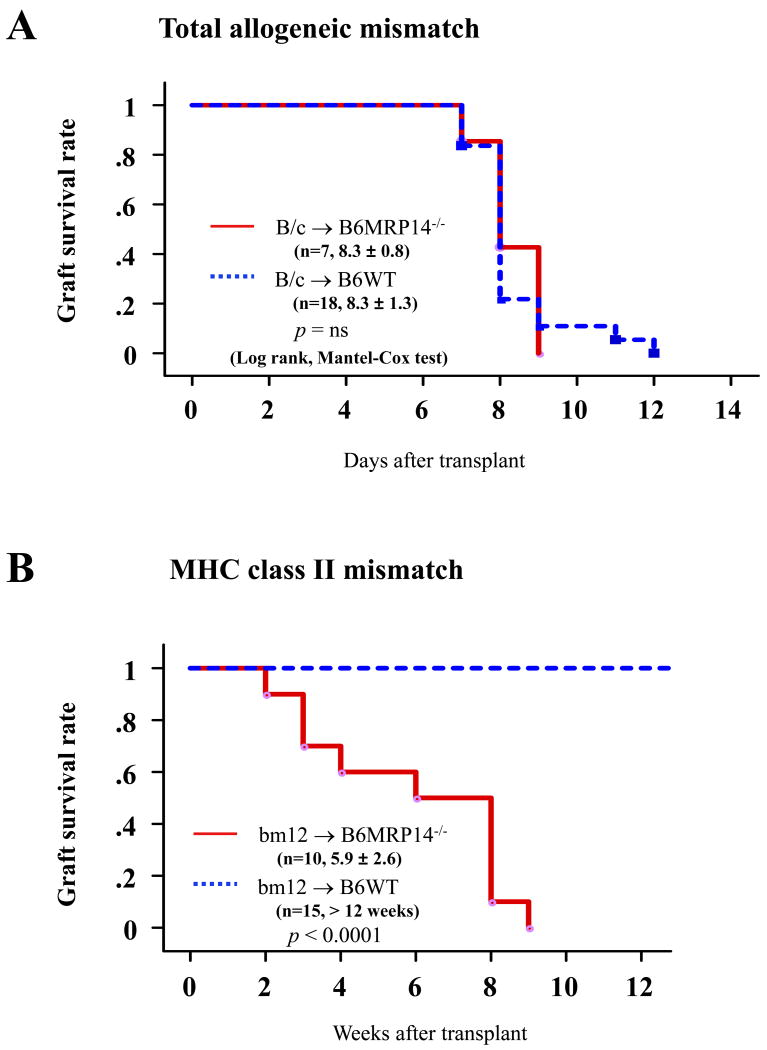

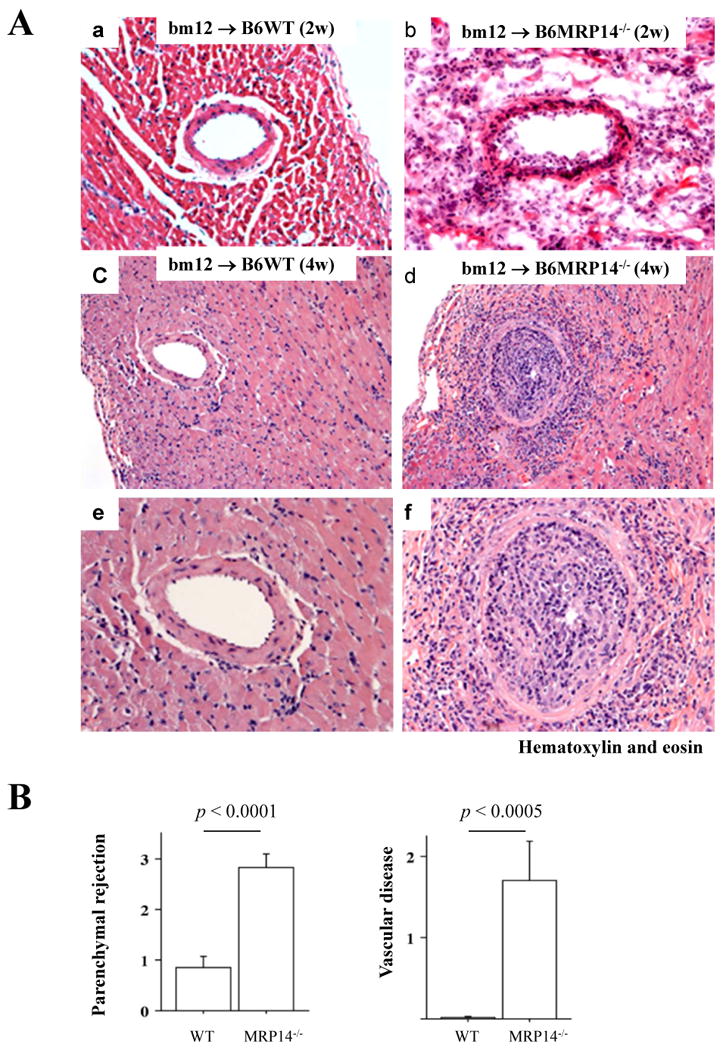

Survival of total-allomismatched murine cardiac allografts (BALB/c donor hearts and B6 recipients) was comparable between B6 WT and MRP-14-/- recipients; allograft survival averaged 8.3 ± 1.3 days (mean ± SD, n=18) in WT recipients and 8.3 ± 0.8 (n=7, p = 0.8565) in MRP-14-/- recipients (Figure 1A). In contrast, in MHC class II-allomismatched murine cardiac allografts (bm12 donor hearts and B6 recipients), MRP-14-/- recipients had significantly reduced allograft survival compared to WT recipients; survival averaged 5.9 ± 2.6 weeks (mean ± SD, n=10) for allografts in MRP-14-/- recipients, compared to > 12 weeks (n=15, p < 0.0001) in WT recipients (Figure 1B). Failing grafts in MRP-14-/- recipients showed severe coronary arteritis with perivascular edema and confluent areas of myocardial necrosis at 2 weeks and 4 weeks after transplantation (Figure 2A). At the same time point, grafts in WT recipients exhibited virtually no arterial inflammation, edema, or coagulative necrosis, despite the presence of multifocal parenchymal inflammatory infiltrates (Figure 2A). Reflecting these differences, allografts in MRP-14-/- recipients 2 weeks after transplantation had significantly higher PR scores (2.8 ± 0.8, mean ± SD, n=8) than did WT recipients (0.8 ± 0.8, n=12, p<0.0001). At this 2-week time point, inflammatory cells and thrombi localized within the vessel lumina in allografts of MRP-14-/- recipients. These lesions differ from chronic allograft arteriopathy lesions in that the latter consist predominantly of smooth muscle–like cells.27, 33, 34 Nevertheless, we scored the extent of early luminal occlusion by inflammatory cells. Grafts in MRP-14-/- recipients had significantly higher scores (1.70 ± 1.37, mean ± SD, n=8) than did WT recipients (0.02 ± 0.04, n=12, p = 0.0004) (Figure 2B). Cardiac allografts of MRP-14-/- recipients start ceasing their beat 2 weeks after transplantation, as shown in Figure 1. Sixty percent of MRP-14-/- recipient allografts survive at the 4-week time point, but more severe vasculopathy develops with time, as compared to WT recipient allografts (Figure 2A, 2C–2F). Thus, deficiency of recipient MRP-14 worsens allograft survival associated with augmented inflammatory cell accumulation, including vascular luminal inflammatory cells.

Figure 1. Host MRP-14 deficiency reduces MHC class II-mismatched cardiac allograft survival.

Kaplan-Meier analysis of graft survival after (A) total-allomismatched heart transplantation in WT (n=18) and MRP14-/- (n=7) recipients and (B) MHC class II mismatched heart transplantation in WT (n=15) and MRP14-/- (n=10) recipients.

Figure 2. Recipient MRP-14 deficiency accelerates and augments acute parenchymal rejection and vascular infiltration after MHC class II-mismatched transplantation.

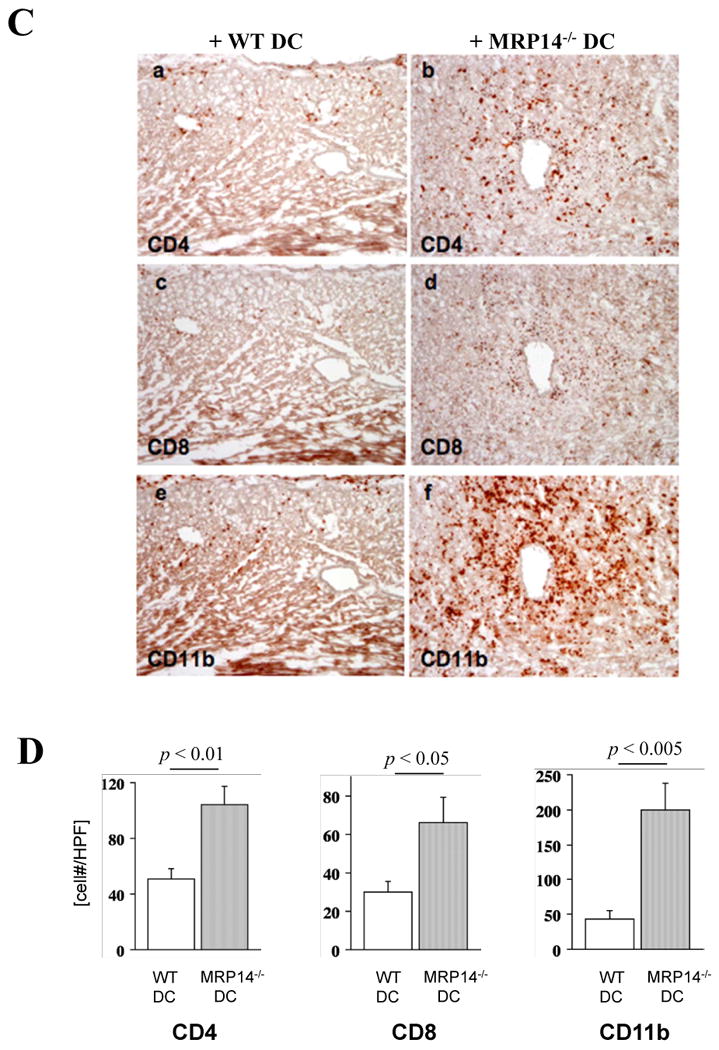

A. Photomicrographs of H & E staining of bm12 cardiac allografts harvested 2 weeks after transplantation in WT (a) and MRP-14-/- B6 recipients (b), and 4 weeks after transplantation in WT (c, e) and MRP-14-/- B6 recipients (d, f); e and f represent a magnification of the vascular lesions of WT and MRP-14-/- B6 recipient allografts, respectively. B. PR and luminal occlusion scores (mean ± SD) were determined, as described in the Methods section, from hearts harvested from WT (n=12) and MRP-14-/- (n=8) recipients. C. Immunohistochemistry examined immune cell infiltration into transplanted hearts in WT (a, c, e) and MRP-14-/- (b, d, f) recipients 2 weeks after transplantation. Anti-CD4 (a, b), anti-CD8 (c, d), and anti-CD11b (for macrophages; e, f) staining was performed. D. Immune cell accumulation was quantified (mean ± SD) by determining the average number of cells per high-power field (× 100) in WT (n=12, open bars) and MRP-14-/- (n=8, closed bars) recipients.

MRP-14 deficiency increases intragraft accumulation of CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes and macrophages

We performed immunohistochemical analysis of immune cell infiltrates in transplanted hearts in WT and MRP-14-/- recipients 2 weeks after engraftment. The number of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and the number of macrophages both increased significantly in MRP-14-/- recipients as compared with WT recipients, as assessed by staining with anti-CD4, anti-CD8, or anti-CD11b antibodies, respectively (Figure 2C, 2D). To verify that differences in leukocyte accumulation in MRP-14-/- mice did not result from differences in peripheral blood leukocyte counts, we performed complete blood count analysis in WT and MRP-14-/- mice. WT recipients (n=4) and MRP-14-/- recipients (n=4) showed no statistically significant differences in peripheral blood neutrophils (2.12 ± 0.67 vs. 1.95 ± 0.60 × 103/μL, mean ± SD, p = 0.71), monocytes (0.11 ± 0.06 vs. 0.09 ± 0.06 × 103/μL, p = 0.60), or lymphocytes (6.85 ± 0.67 vs. 6.95 ± 0.78, p = 0.85), respectively.

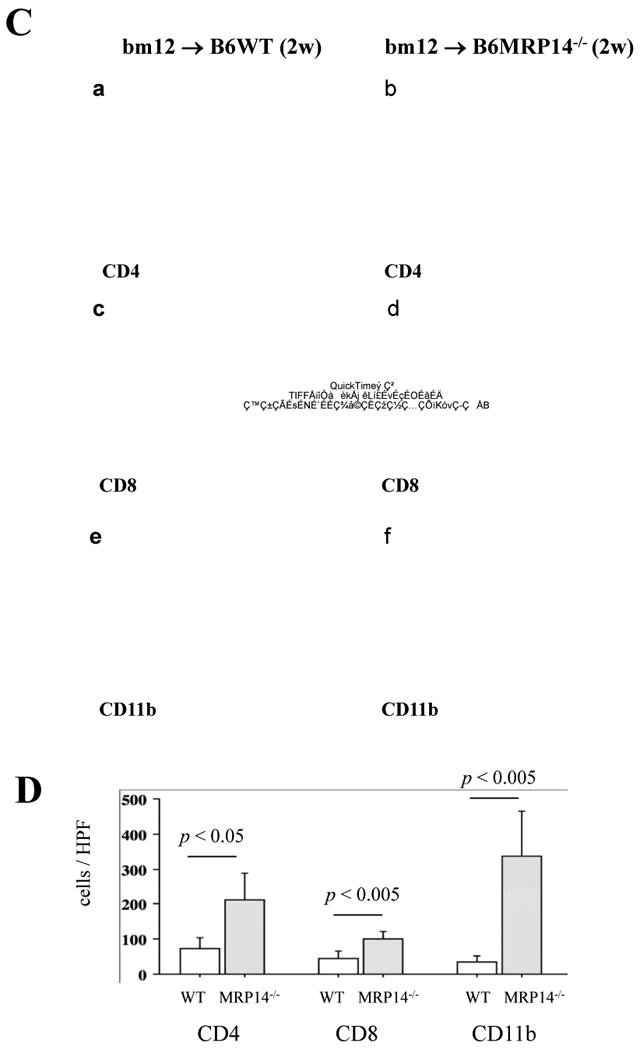

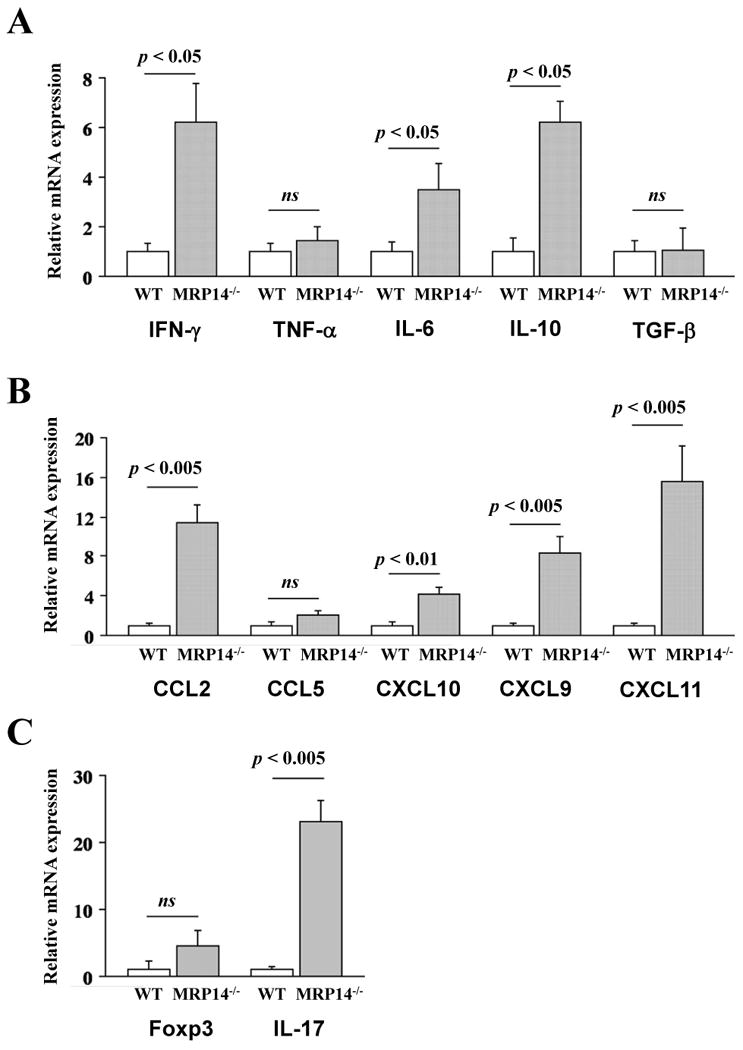

Elevated cytokine and chemokine mRNA expression in allografts of MRP-14-/- recipients

The augmented graft immune cell infiltration in MRP-14-/- recipients could result from changes in local chemokine and cytokine expression. To test this possibility, we performed quantitative real-time PCR to measure chemokine and cytokine mRNA expression from allografts harvested 2 weeks after transplantation. MRP-14-/- recipients had significantly increased allograft expression of interferon-γ (IFN-γ), interleukin-6 (IL-6), IL-17, monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1/CCL2), interferon-γ-inducible protein-10 (IP-10/CXCL10), monokine induced by interferon-γ (Mig/CXCL9) mRNA, and IFN-inducible T-cell– chemoattractant (I-TAC/CXCL11), compared to WT recipients. MRP-14-/- and WT recipients had comparable levels of tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), Transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), Foxp-3, and regulated upon activation normal T-cell expressed and secreted (RANTES/CCL5) mRNA expression (Figure 3A–3C).

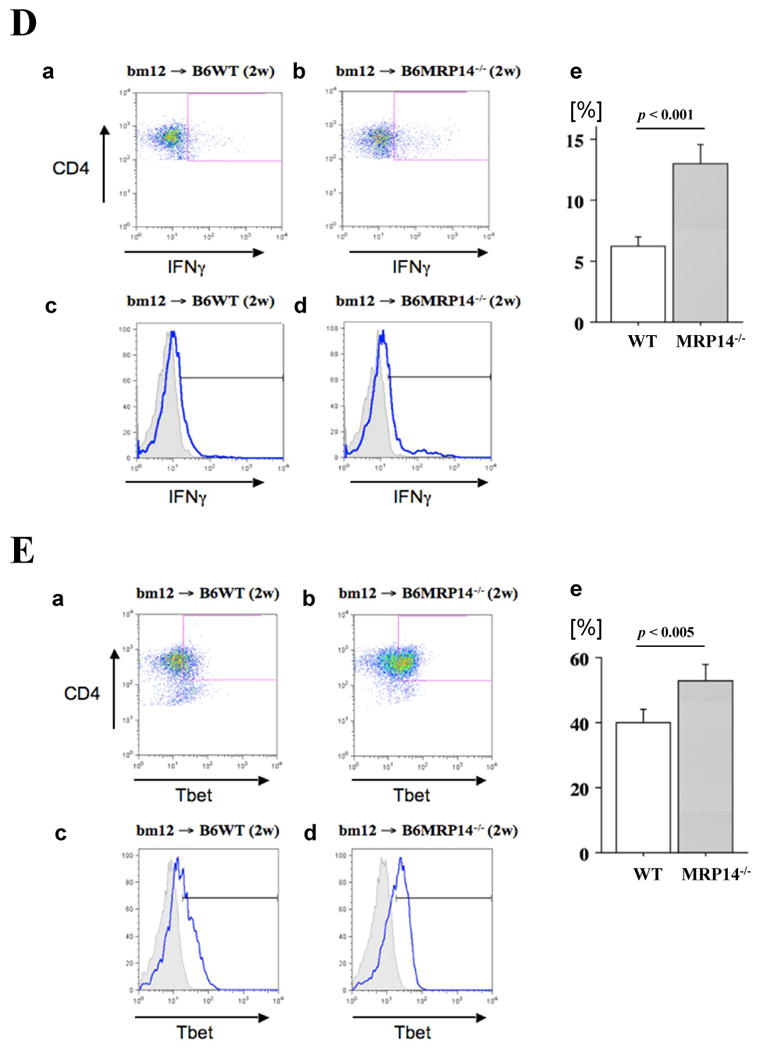

Figure 3. Cytokine and chemokine mRNA expression and TH17 cells in transplanted hearts.

Messenger RNA expression of cytokines (A; IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-6, IL-10, and TGF-β) and chemokines (B; MCP-1, RANTES, IP-10, Mig, and I-TAC), and Foxp3 and IL-17 (C) in bm12 allografts, was examined by quantitative real-time PCR 2 weeks after transplantation into WT (open bars) or MRP-14-/- (solid bars) recipients. Data represent mean ± SEM, n=6 per group. D–G. Flow cytometric analysis of IFN-γ (D), T-bet (E), IL-17 (F), and RORγt (G) in CD4+ T cells of graft infiltrating cells in WT and MRP-14-/- recipient allografts 2 weeks after transplantation. The shaded gray curve shows negative control using isotype-matched immunoglobulin, and the blue lines show cytokine expression levels in the merged histogram (D, c and d; E, c and d, F, c and d)

IFN-γ, IL-17, T-bet, and RORγt levels increased in CD4+ T cells in allografts of MRP-14-/- recipients

Flow cytometry analysis of graft-infiltrating cells revealed significantly higher levels of IFN-γ and IL-17 in CD4+ T cells in MRP-14-/- host allografts, as compared with WT host allografts (Figure 3D-3G). Levels of CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ T cells of WT and MRP-14-/- host allografts did not differ (Supplemental Figure S2)

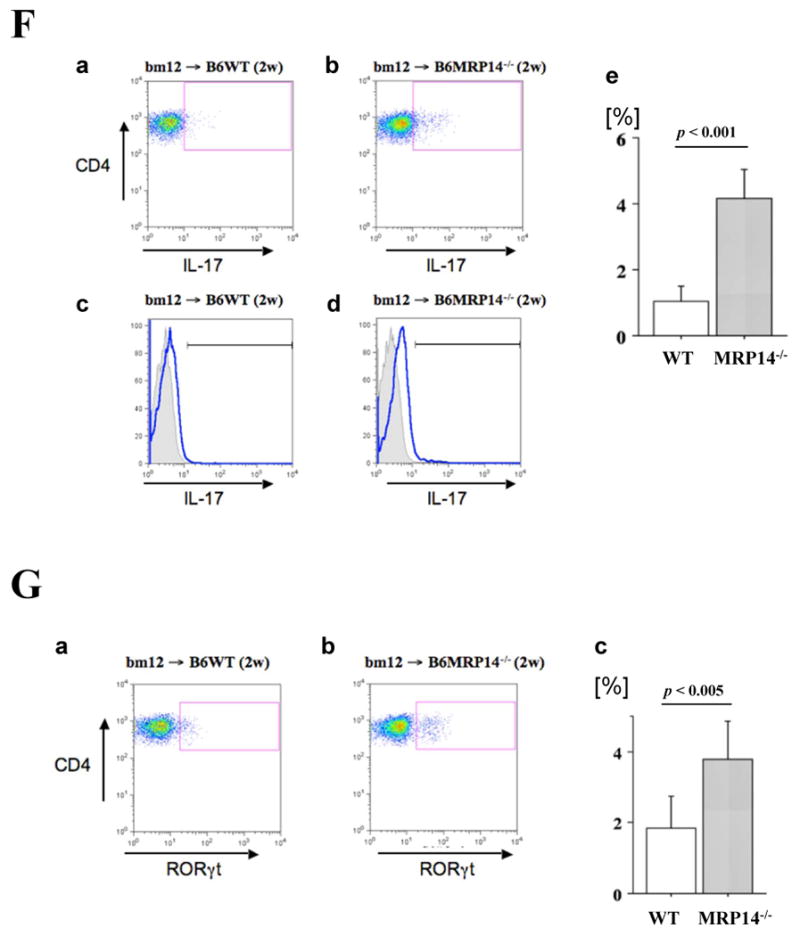

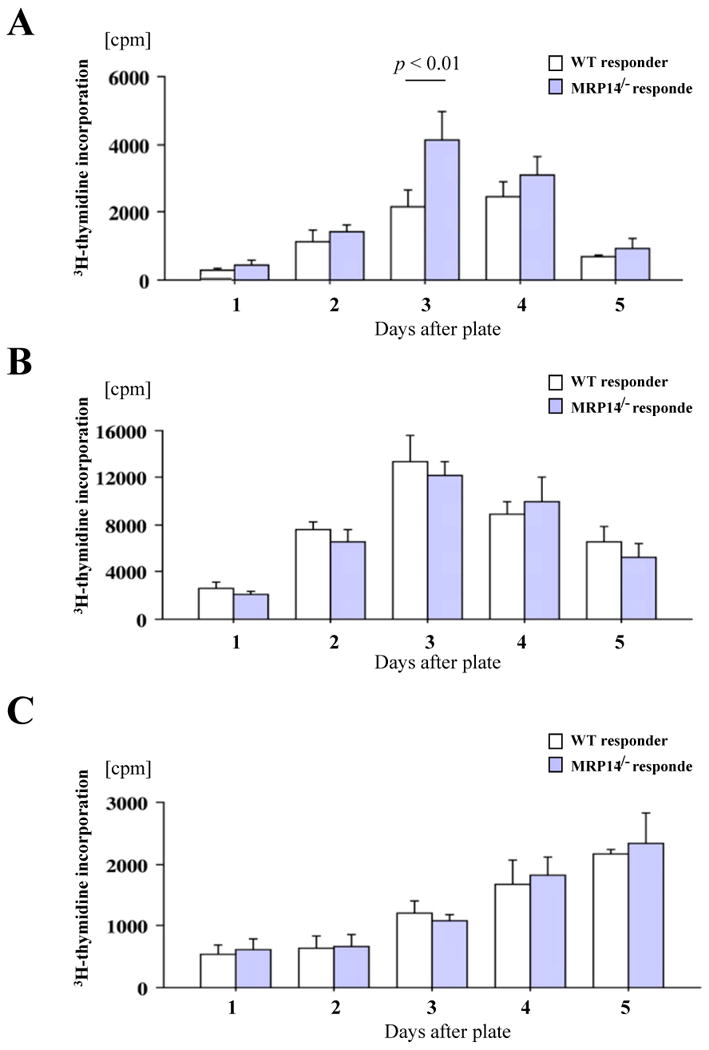

Increased size and cell number of adjacent para-aortic lymph nodes in MRP-14-/- hosts

MRP-14-/- recipients showed a prominent lymphadenopathy of the adjacent para-aortic lymph nodes 2 weeks after transplantation (Figure 4A). While WT lymph node size increased 1.2 times after transplantation compared to non-transplanted lymph nodes, lymph node size increased approximately 5-fold in MRP-14-/- transplant recipients. Flow cytometry of adjacent lymph nodes showed that WT and MRP-14-/- recipients had comparable cellular compositions, but the number of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, B220+ B cells, and CD11b+ macrophages were relatively increased in MRP-14-/- recipients (Figure 4B).

Figure 4. Characterization of draining lymph nodes.

A. Photomicrographs of naive abdominal para-aortic lymph nodes from WT (a) or MRP-14-/- recipients (c) and abdominal para-aortic lymph nodes adjacent to heterotopic bm12 cardiac allografts of WT (b) or MRP-14-/- recipients (d) 2 weeks after transplantation. B. Cell number per lymph node of naive (Pre, pre-transplant) or 2 weeks after transplantation (Post) WT or MRP-14-/- recipients. a, CD4+ T cells; b, CD8+ T cells; c, B220+ B cells; d, CD11b+ macrophages. Data represent mean ± SEM, n=6 per group.

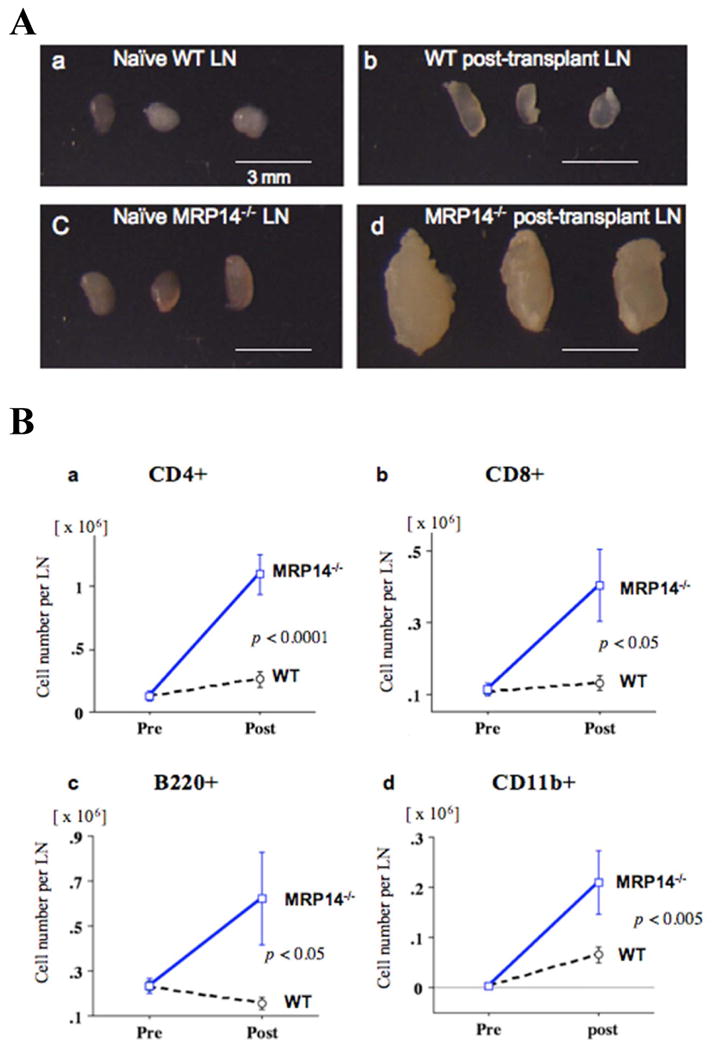

MRP-14-/- splenocytes have increased MLRs but normal responses to anti-CD3 and anti-CD40 antibodies

Enlargement of local adjacent lymph nodes suggests augmented interaction of APCs and T cells, with subsequent enhanced alloresponse, and is consistent with the increased allograft inflammatory cell infiltration in MRP-14-/- recipients.35 MRP-14 deficiency could also directly modulate T-cell, B-cell, and/or monocyte/macrophage/DC function, and may alter the local cytokine milieu.36 We therefore examined whether MRP-14 deficiency modulates MLR using WT or MRP-14-/- splenocytes as responders and irradiated bm12 splenocytes as stimulator cells. In this assay, MRP-14-/- splenocytes showed a significantly higher proliferation rate compared to WT splenocytes after 3 days of culture (Figure 5A). To dissect the mechanisms by which MRP-14-/- splenocytes showed augmented proliferative responses, we stimulated splenocytes directly with anti-CD3 mAbs (T-cell stimulation) or anti-CD40 (3/23) mAbs (B-cell stimulation). Interestingly, WT and MRP-14-/- splenocytes proliferated comparably under these conditions (Figure 5B and 5C), suggesting that MRP-14–deficient T cells and B cells have normal intrinsic proliferative capability.

Figure 5. MRP-14-/- splenocytes have increased proliferation in MLR, but comparable responses to anti-CD3 or anti-CD40 antibodies.

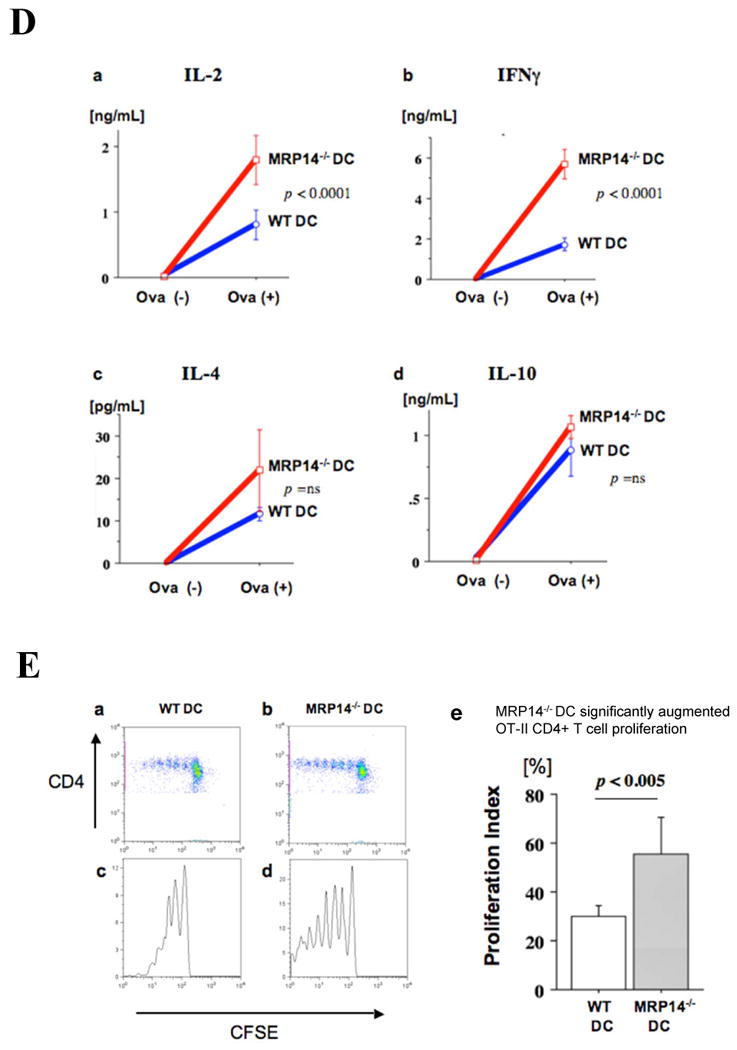

A. MLR using WT or MRP-14-/- B6 splenocyte responders and irradiated bm12 splenocyte stimulators. B. T-cell responses of WT and MRP-14-/- B6 splenocytes against immobilized anti-CD3 TCR stimulating antibodies. C. B-cell responses of WT and MRP-14-/- B6 splenocytes against immobilized anti-CD40 stimulating antibodies. Experiments were conducted in quadruplicate wells of a 96-well plate, and were repeated at least three times. D. Cytokine expression levels (a, IL-2; b, IFN-γ; c, IL-4; d, IL-10) of the supernatant of WT or MRP14-/- DCs co-cultured with OT-II CD4+ T cells in the presence (Ova+) or absence (Ova-) of 10 nM ovalbumin. E. Flow cytometry of CFSE-labeled OT-II CD4+ T cells co-cultured with WT (a, c) or MRP14-/- DCs demonstrates cellular proliferation. e, proliferation index; data represent mean ± SEM, n=4 per group.

MRP14-/- DCs promote greater CD4+ T cell proliferation and higher IFN-γ production

MLR using bm12 stimulator splenocytes enhanced proliferation of MRP14-/- splenocyte responders compared to WT responders, while direct stimulation of T cells and B cells showed comparable responses. We therefore hypothesized that MRP14 deficiency increases the immunogenic and pro-inflammatory antigen-presenting capacity of DCs. To test this hypothesis, we cultured OT II T cells and bone marrow–derived WT or MRP14-/- DCs in the presence of the OT II cell's nominal antigen, ovalbumin (OVA). We incubated CFSE-labeled OT-II splenocytes at 5×106 cells/ml in 6-well plates with B6 WT or MRP14-/- DCs with 10nM OVA-peptide (Sigma) for 4 days, then harvested the supernatant for IL-2 and IFN-γ measurement by ELISA and CFSE-labeled OT-II cell proliferation by flow cytometry. This experiment demonstrated that compared to WT, MRP14-/- DCs induced significantly more IL-2 and IFN-γ and promoted higher degrees of CD4+ T cell proliferation, indicating that MRP14 deficiency increases the immunogenic APC function of DCs (Figure 5D and 5E). In contrast, IL-10 production did not differ between WT and MRP14-/- DCs, and flow cytometry showed no difference in the expression of the inhibitory co-stimulatory molecules PDL1 and PDL2 (data not shown).

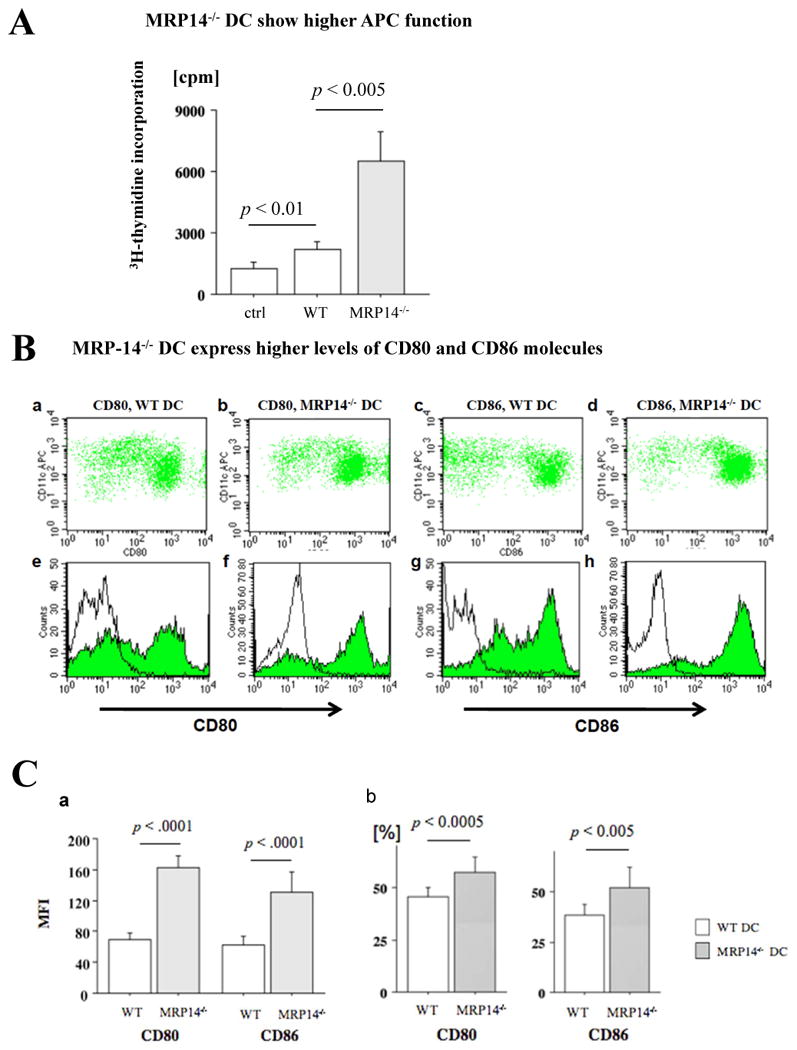

MRP-14-/- DCs express higher levels of co-stimulatory molecules and have augmented alloantigen-presenting function

The first encounter of recipient leukocytes with donor cells in an allograft is through ECs; DCs serve as the most potent APCs and play a central role in the initiation of immunity or tolerance.37 To assess whether DCs (B6) can process and present EC alloantigens in vitro, we pre-cultured B6 WT or MRP-14-/- DCs with bm12 ECs for 72 hours to allow DCs to capture and process alloantigens. We then co-cultured irradiated allo-EC-primed DCs as stimulators and naive B6 T cells as responders, measuring T-cell proliferation by 3H-thymidine incorporation (non-primed DCs served as a negative control). Allo-EC–primed MRP-14-/- DCs induced significantly higher T-cell proliferation compared to allo-EC–primed WT DCs (Figure 6A). The results suggest that MRP-14-/- DCs provide more effective T-cell priming.

Figure 6. T-cell proliferation assay shows increased responses to bm12 EC–primed MRP-14-/- DCs.

A. MLR to bm12 ECs using non-primed WT DCs (ctrl), bm12 EC–primed MRP-14-/-, or bm12 EC–primed WT, DC stimulators. Data represent peak response 3 days after and average values (mean ± SEM) of three independent experiments. B. MRP-14-/- DCs have augmented APC function. Expression of co-stimulatory molecules on IFN-γ–stimulated DCs from WT (a, c, e, g) and MRP-14-/- (b, d, f, h) mice was assessed by flow cytometry; cells were double-stained with PE-conjugated anti-CD80, anti-CD86, and APC-conjugated anti-CD11c. The shaded gray curve shows negative control using isotype-matched immunoglobulin, and the blue lines show CD80 (e, f) or CD86 (g, h) expression levels in the merged histogram (e-h). C. Values represent mean fluorescence intensity (a) and percentages of CD80-positive or CD86-positive cells (b). Data represent mean ± SEM, n=4 per group; WT (open bars) and MRP-14-/- (solid bars).

We then tested the hypothesis that enhanced MRP-14-/- DC APC function associates with increased co-stimulatory molecule expression. We stimulated WT or MRP-14-/- DCs with IFN-γ for 18 hours and assessed DC MHC class II and co-stimulatory molecule expression by flow cytometry. IFN-γ–treated MRP-14-/- DCs showed significantly higher expression of CD80 (mean fluorescence intensity, 162.5 ± 15.5), CD86 (130.9 ± 26.7), and ICOSL (35.1 ± 1.5, graph not shown), compared to IFN-γ–treated WT DCs (CD80, 69.9 ± 9.3, p < 0.0001; CD86, 62.2 ± 11.5, p < 0.0001, n=4; ICOSL, 30.6 ± 1.8, p = 0.029, n=4, respectively) (Figure 6B and 6C). The percentages of CD80+ and/or CD86+ cells were also greater in MRP-14-/- DCs than in WT DCs (Figure 6C). MHC class II expression showed identical levels (data not shown). The MLR and DC co-stimulatory molecule expression data demonstrate that MRP-14 regulates DC antigen-presenting capacity and DC-mediated T-cell activation.

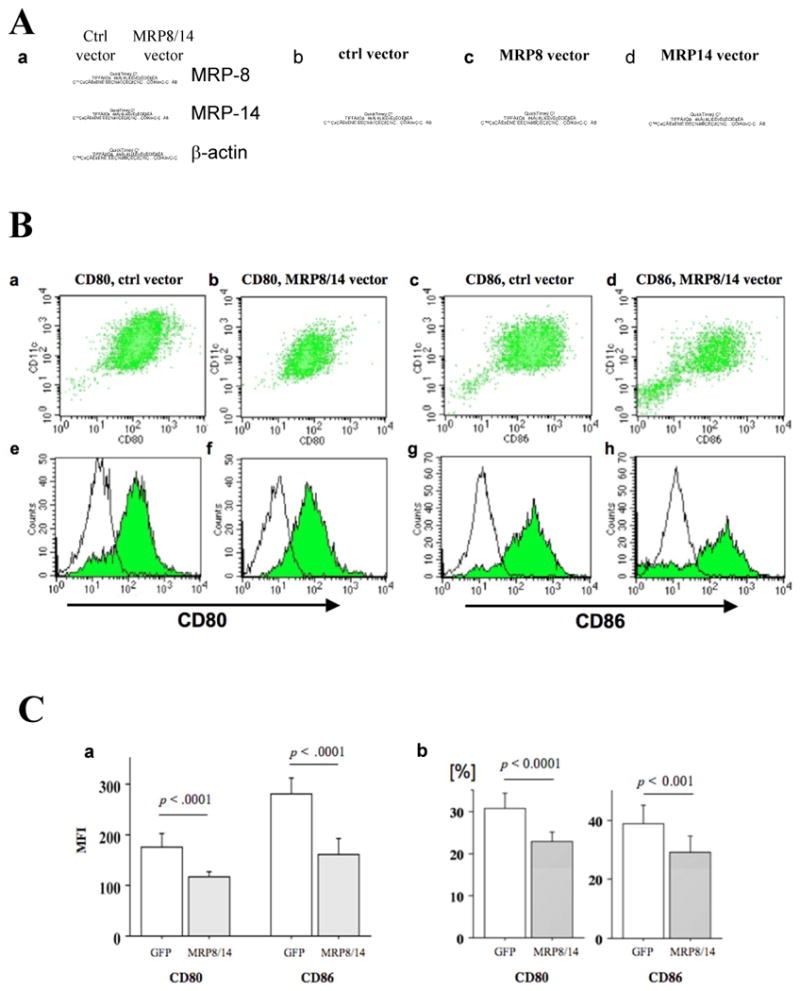

Retroviral infection with MRP-8 and MRP-14 retroviral vectors reduced CD80 and CD86 expression in MRP-14-/- DCs

A previous study indicated that MRP-14-deficient animals lack both MRP-8 and MRP-14 protein expression, even though they express MRP-8 mRNA.25 Moreover, DCs overexpressing MRP-8/14 exhibit DC maturation.38 We therefore tested whether MRP-14-/- DCs reconstituted with MRP-8/14 show reduced expression of co-stimulatory molecules. We reconstituted MRP-14-/- DCs with MRP-8 and MRP-14 retrovitral vector infection, and performed flow cytometry to assess co-stimulatory molecule expression 18 hours after IFN-γ stimulation. Reconstituted MRP-14-/- DCs with MRP-8/14 retrovitral vector showed significantly lower levels of CD80 (mean fluorescence intensity, 117.2 ± 9.1) and CD86 (161.3 ± 30.2), compared to control vector-infected MRP-14-/- DCs (CD80, 175.5 ± 25.4, p < 0.0001; CD86, 278.4 ± 32.9, p < 0.0001, n=4) (Figure 7B and 7C). The percentages of CD80+ and/or CD86+ cells also were comparable, as shown by mean fluorescence intensity. These findings indicate that MRP-8/14 inhibits costimulatory molecule expression on the surface of DCs.

Figure 7. MRP-14-/- DCs reconstituted with MRP8/14 retroviral vector showed reduced CD80 and CD86 expression.

A. Western blot demonstrates higher expression of MRP-8 and MRP-14 by MRP-14-/- DCs receiving MRP-8/14 retroviral vector infection, compared to control MRP-14-/- DCs receiving empty vector infection (a). MRP-14-/- DCs receiving empty vector (control, b), MRP-8-vector (c), and MRP-14-vector express enhanced GFP, indicating success of infection. B. MRP-14-/- DCs receiving MRP-8/14 retroviral vector infection have reduced APC function. Expression of co-stimulatory molecules on IFN-γ–stimulated DCs of control-vector–treated (a, c, e, g) and MRP-8/14-vector-treated (b, d, f, h) MRP-14-/- DCs was assessed by flow cytometry and double-staining with PE-conjugated anti-CD80, anti-CD86, and APC-conjugated anti-CD11c. The shaded gray curve shows negative control using isotype-matched immunoglobulin, and the blue lines show CD80 (e, f) or CD86 (g, h) expression levels in the merged histogram (e-h). C. Values represent mean fluorescence intensity (a) and percentages of CD80-positive or CD86-positive cells (b). Data represent mean ± SEM, n=4 per group; control-vector-treated (open bars) and MRP-8/14-vector–treated (solid bars).

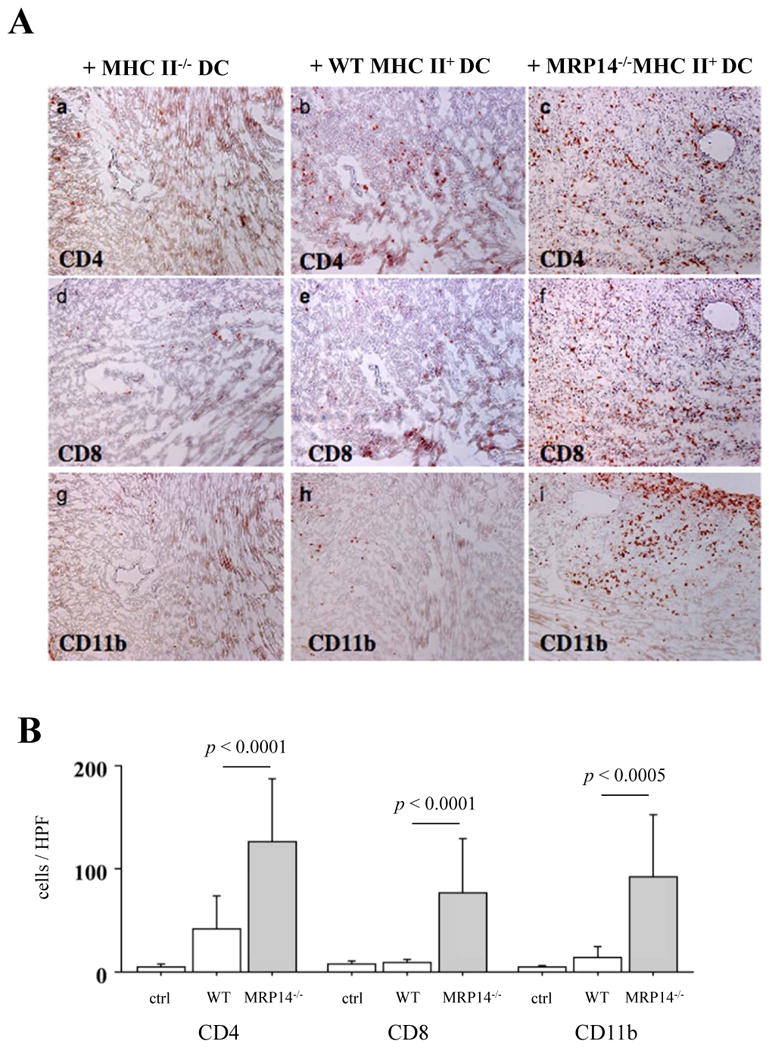

Cardiac allografts of B6 MHC class II-/- hosts receiving MRP-14-/- DCs show augmented inflammatory cell content

To test whether MRP-8/14 in recipient DCs regulates antigen-presenting function and impacts allograft rejection, we performed adoptive transfer experiments using MHC class II–deficient animals. Bm12 cardiac allografts in MHC class II-/- hosts do not develop acute rejection because host APCs lack MHC class II and do not recognize bm12 antigen. We specifically tested whether MRP-8/14-deficient DCs in such MHC class II-/- hosts could augment APC function and drive acute rejection. DCs from B6 MHC class II-/-, B6 WT, or MRP-14-/- mice were transferred into B6 MHC class II-deficient mice; 1 week later, bm12 hearts were transplanted into these hosts. We examined graft-infiltrating inflammatory cells 2 weeks after cardiac transplantation in each host. Allografts in animals receiving MRP-14–deficient DCs showed significantly higher levels of inflammatory cell accumulation, compared to allografts in hosts receiving MHC class II-/- DCs or WT DCs (Figure 8B and 8C).

Figure 8. Cardiac allografts in B6 MHC class II-/- hosts or B6WT receiving MRP-14-/- MHC II+ DCs showed augmented inflammatory cell infiltration.

A. Immunohistochemistry examined inflammatory cell infiltration into transplanted hearts in MHC class II-/- hosts receiving MHC class II-/- DCs (a, d, g), B6 WT MHC II+ DCs (b, e, h), and MHC II+ MRP-14-/- DCs (c, f, i) 2 weeks after transplantation. Anti-CD4 (a, b, c), anti-CD8 (d, e, f), and anti-CD11b (g, h, i for macrophages) staining was performed. B. Inflammatory cell accumulation was quantified by determining the average number of cells per high-power field (× 100) in MHC class II-/- hosts receiving MHC class II-/- DCs (open bar), B6 WT MHC II+ DCs (open bar) and MRP-14-/- MHC II+ DCs (solid bar). Data represent mean ± SD, n=6 per group. C. Immunohistochemistry examined inflammatory cell infiltration into transplanted hearts in B6WT hosts receiving B6WT DCs (a, c, e) and MRP-14-/- DCs (b, d, f) 4 weeks after transplantation. Anti-CD4 (a, b), anti-CD8 (c, d), and anti-CD11b (e, f for macrophages) staining was performed. D. Inflammatory cell accumulation was quantified by determining the average number of cells per high-power field (× 100) in B6WT hosts receiving B6WT DCs (open bar) and MRP-14-/- DCs (solid bar). Data represent mean ± SD, n=6 per group.

Cardiac allografts of B6 WT hosts receiving MRP-14-/- DCs also show augmented inflammatory cell content

We also performed adoptive transfer experiments using B6 WT animals. DCs from B6 WT or MRP-14-/- mice were transferred into B6 WT mice; 1 week later, bm12 hearts were transplanted into these hosts. We examined graft-infiltrating inflammatory cells 2 weeks after cardiac transplantation in each host. Allografts in animals receiving MRP-14–deficient DCs showed significantly higher levels of inflammatory cell accumulation compared to allografts in hosts receiving WT DCs (Figure 8C and 8D). The results support the conclusions that MRP-14 mutes APC function, and that the absence of MRP-14 leads to augmented allograft rejection.

Discussion

This study found that MRP-14-/- recipients have accelerated failure of MHC class II mismatched cardiac allografts, associated with increased intragraft accumulation of inflammatory cells and Th-17 cells, and elevated mRNA expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IFN-γ, IL-6), IL-17, and IFN-γ–associated chemokines (CCL2, CXCL9, CXCL10, and CXCL11). We also found significant enlargement of adjacent para-aortic lymph nodes in MRP-14-/- recipients, with increased expression of costimulatory molecules (CD80, CD86, ICOSL) in IFN-γ–stimulated MRP-14-/- DCs, and augmented APC function. Reconstitution of MRP-14-/- DCs with MRP-8 and MRP-14 retroviral vectors suppressed APC function.

MRP-14-/- mice have normal organ development and live a normal lifespan despite lacking both MRP-14 and MRP-8 proteins.25 The lack of MRP proteins did not affect baseline lymph node size or the number of circulating monocytes, neutrophils, lymphocytes, or natural killer cells; myeloid cell numbers in lymphoid organs such as the spleen and bone marrow were also normal. Several lines of evidence suggest that myeloid cells from MRP-14-/- mice are of similar maturity to those in WT mice; MRP-14-/- and WT neutrophils have similar expression of adhesion receptors (e.g., L-selectin and the integrins Mac-1, LFA-1, and α4β1), either constitutively or following activation with MIP-2, TNF-α, or phorbol ester.25

Murine MRP-14 protein constitutes 10 to 20% of neutrophil soluble protein.5 Murine leukocytes also express other S100 proteins, such as S100A1 and A4.39, 40 Consequently, an increase in other S100 proteins might compensate for the loss of MRP-14 and MRP-8, but the expression of both S100A1 and A4 remained unaltered in MRP-14-/- bone marrow cells.25 Studies of mice deficient in other S100 protein family members indicate a similar lack of compensatory increases in associated S100 family members.25 Thus, myeloid and other innate inflammatory cell types apparently develop and function reasonably normally in the absence of their distinctive S100 proteins.

We recently demonstrated that MRP-8/14 broadly regulates vascular inflammation and contributes to the biological response to vascular injury in experimental atherosclerosis, after arterial injury, or in small-vessel vasculitis by promoting leukocyte recruitment. 41 Nevertheless, the response of neutrophils, monocytes, and other leukocytes to thioglycolate-induced peritonitis was comparable to WT mice,25 indicating that the effect of MRP-14 likely depends upon the precise inflammatory stimulus. MRP-14 inhibits a number of macrophage-activating activities, including proliferation and phagocytic activity,42 and respiratory burst of O2- or H2O2 release from activated macrophages.19 MRP-14 also inhibits immunoglobulin synthesis by B cells in vitro.43 Some inhibitory effects may arise from deficient actin polymerization and phagolysosome maturation.44, 45

CD4+ T cells regulate alloimmune response. After transplantation, the local cytokine milieu produced by innate cells activates naive CD4+ T cells and promotes them to differentiate into Th1, Th2, and Th17 effector subsets, as well as regulatory T cells (Treg). The expression of specific transcription factors (e.g., T-bet for Th1 cells, GATA-3 for Th2, RORγt for Th17, and Foxp3 for Treg) identifies each Th subset. Both Th1 and Th2 effector cells cause acute rejection of bm12 allografts in B6 hosts.46, 47 Th17 cells may contribute to the immune response during allograft rejection. IL-12 and IL-23 promote Th1 and Th17 differentiation, respectively; they also share the same p40 subunit, paired with the p35 subunit to form IL-12 or the p19 subunit to form IL-23. IL12/23/p40 blockade prolongs cardiac allograft survival, with a decrease in both T-bet and RORγt expression in the allografts, indicating that both Th1 and Th17 cells cause allograft rejection.48 Treg cells can inhibit IL-2, IFN-γ, and IL-13 by CD4+ T cells, suppress both types of responses, and attenuate skin allograft rejection.49 In contrast, Treg cells enhance IL-17 production in a MHC II-mismatched MLR50 and promote the Th17-mediated pathway of allograft rejection.51

The co-stimulatory molecules CD80 (B7-1) and CD86 (B7-2), expressed on APCs, interact with the receptors CD28 and CD152 (CTLA-4) on T cells. Co-stimulation through the B7/CD28 pathway is an important mechanism for the activation of lymphocytes by alloantigens; blockade of the B7:CD28 co-stimulatory pathway attenuates acute rejection of cardiac allografts.52 This study showed augmented B7 molecule expression of MRP-14-/- DCs and reduced B7 molecule expression of MRP-8/14 gene-transferred MRP-14-/- DCs, indicating that MRP-14 inhibits CD80 and CD86 expression on DCs. Emerging evidence demonstrates that DCs have distinct inflammatory phenotypes, denoted as “DC1” or “DC2”. DC1s serve as immunogenic or pro-inflammatory APCs; they produce pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-12, activate Th1 cells, initiate inflammation, orchestrate the defense against infectious agents or allo-antigens, and promote allograft rejection. In contrast, DC2s serve as tolerogenic or inhibitory APCs; they produce IL-10, induce Th2 cells and/or regulatory T cells, and promote transplant tolerance.53-55 Based on the finding that MRP14-/- DCs accelerate cardiac allograft rejection and increase IFN-γ production and T-cell proliferation, compared to WT DCs in co-culture with OT-II T cells in the presence of their nominal antigen, ovalbumin, it appears that MRP14-/- DCs function as DC1s. The recent report that MRP-14-deficient DCs have increased toll-like receptor-mediated cytokine expression further supports a role for MRP-14 in the control of DC-mediated T-cell activation and inflammation.56

S100 proteins regulate cathepsins and MMPs.57-59 In particular, the transcriptional activation of MMP-2 requires MRP-8/14,60 and antigen presentation via MHC class II involves proteolytic degradation of both the internalized protein and invariant chains.61 We performed quantitative real-time PCR for cathepsins B, L, S, and K in DCs, but found no differences between WT and MRP-14-/- DCs (data not shown).

MRP-14 also serves as a key molecule in regulating tolerogenic DCs rather than immunogenic DCs. This conjecture is supported by the observation that IL-10 and TGF-β induce a tolerogenic DC phenotype;53 IL-10 raises MRP-8/14 levels in DCs,36 and MRP-14 overexpression inhibits DC differentiation,38 suggesting that tolerogenic DCs may associate with increased MRP-8/14 expression. MRP-14 deficiency, as in these experiments, would therefore show overall reduced tolerance and increased allograft responses.

Clinical Implications

Graft arterial disease (GAD) limits long-term survival in cardiac transplant recipients. GAD shares some pathophysiologic features with conventional atherosclerosis; APCs present alloantigens (e.g., antigens on donor ECs) or auto antigens (e.g., oxidized LDL cholesterol) to T cells, initiating differentiation and activation of T cells, B cells, and inflammatory cell responses with co-stimulatory signaling. Nevertheless, there are important differences in the pathology and distributions of these diseases. Although hyperlipidemia, a well-established risk factor for conventional atherosclerosis, is common after transplantation, GAD lesions tend to be lipid-poor. GAD involves large-sized and medium-sized vessels as well as the microvasculature, and affects the media and adventitia as well as the intima. MRP-14 deficiency can attenuate wire-injury– induced vascular lesions and atherosclerotic lesions in atherogenic animals. In contrast, the current study demonstrates that recipient MRP-14 deficiency exacerbates allograft vasculopathy. This study examined the effect of MRP-14 deficiency on PR and GAD after MHC class II-mismatched murine heart transplantation without immunosuppression. Clinical application will require future studies evaluating the effects of MRP-14 expression in the setting of immunosuppressive therapy.

Conclusion

These results indicate that MRP-14 regulates B7 molecule expression and reduces antigen presentation by DCs and subsequent T-cell priming. The absence of MRP-14 markedly increased T-cell activation and exacerbated allograft rejection, indicating a previously unrecognized role for MRP-14 in immune cell biology.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank E. Shvartz, Y. Tesmenitsky, G. Suliman, and E. Simon-Morrissey for their technical expertise, and S. Karwacki for editorial assistance.

Sources of Funding: This work was supported by an American Society of Transplantation Basic Science Faculty Development Grant (K.S.), an American Heart Association Scientist Development grant (K.S.), The Lerner Symposium Award (K.S.), a Brigham Research Institute grant (R.N.M.), a Harris Family Foundation Award (K.C.), and grants from the Donald W. Reynolds Foundation (P.L.) and from the National Institutes of Health (HL-43364, HL-34636 to P.L.; HL57506, HL60942 to D.I.S.; 1K08HL086672 to K.C.).

Abbreviations

- B6

C57BL/6

- B/c

BALB/c

- WT

wild-type

- TNF-α

tumor necrosis factor-alpha

- PR

parenchymal rejection

- GAD

graft arterial disease

- IL

interleukin

- CXCL

C-X-C motif chemokine ligand

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: None.

References

- 1.Edgeworth J, Gorman M, Bennett R, Freemont P, Hogg N. Identification of p8,14 as a highly abundant heterodimeric calcium binding protein complex of myeloid cells. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:7706–7713. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hunter MJ, Chazin WJ. High level expression and dimer characterization of the S100 EF-hand proteins, migration inhibitory factor-related proteins 8 and 14. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:12427–12435. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.20.12427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lagasse E, Weissman IL. Mouse MRP8 and MRP14, two intracellular calcium-binding proteins associated with the development of the myeloid lineage. Blood. 1992;79:1907–1915. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Odink K, Cerletti N, Bruggen J, Clerc RG, Tarcsay L, Zwadlo G, Gerhards G, Schlegel R, Sorg C. Two calcium-binding proteins in infiltrate macrophages of rheumatoid arthritis. Nature. 1987;330:80–82. doi: 10.1038/330080a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nacken W, Sopalla C, Propper C, Sorg C, Kerkhoff C. Biochemical characterization of the murine S100A9 (MRP14) protein suggests that it is functionally equivalent to its human counterpart despite its low degree of sequence homology. Eur J Biochem. 2000;267:560–565. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01040.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hogg N, Allen C, Edgeworth J. Monoclonal antibody 5.5 reacts with p8,14, a myeloid molecule associated with some vascular endothelium. Eur J Immunol. 1989;19:1053–1061. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830190615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zwadlo G, Bruggen J, Gerhards G, Schlegel R, Sorg C. Two calcium-binding proteins associated with specific stages of myeloid cell differentiation are expressed by subsets of macrophages in inflammatory tissues. Clin Exp Immunol. 1988;72:510–515. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Healy AM, Pickard MD, Pradhan AD, Wang Y, Chen Z, Croce K, Sakuma M, Shi C, Zago AC, Garasic J, Damokosh AI, Dowie TL, Poisson L, Lillie J, Libby P, Ridker PM, Simon DI. Platelet expression profiling and clinical validation of myeloid-related protein-14 as a novel determinant of cardiovascular events. Circulation. 2006;113:2278–2284. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.607333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roth J, Burwinkel F, van den Bos C, Goebeler M, Vollmer E, Sorg C. MRP8 and MRP14, S-100-like proteins associated with myeloid differentiation, are translocated to plasma membrane and intermediate filaments in a calcium-dependent manner. Blood. 1993;82:1875–1883. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eue I, Pietz B, Storck J, Klempt M, Sorg C. Transendothelial migration of 27E10+ human monocytes. Int Immunol. 2000;12:1593–1604. doi: 10.1093/intimm/12.11.1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Newton RA, Hogg N. The human S100 protein MRP-14 is a novel activator of the beta 2 integrin Mac-1 on neutrophils. J Immunol. 1998;160:1427–1435. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vogl T, Tenbrock K, Ludwig S, Leukert N, Ehrhardt C, van Zoelen MA, Nacken W, Foell D, van der Poll T, Sorg C, Roth J. Mrp8 and Mrp14 are endogenous activators of Toll-like receptor 4, promoting lethal, endotoxin-induced shock. Nat Med. 2007;13:1042–1049. doi: 10.1038/nm1638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boyd JH, Kan B, Roberts H, Wang Y, Walley KR. S100A8 and S100A9 mediate endotoxin-induced cardiomyocyte dysfunction via the receptor for advanced glycation end products. Circ Res. 2008;102:1239–1246. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.167544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kerkhoff C, Sorg C, Tandon NN, Nacken W. Interaction of S100A8/S100A9-arachidonic acid complexes with the scavenger receptor CD36 may facilitate fatty acid uptake by endothelial cells. Biochemistry. 2001;40:241–248. doi: 10.1021/bi001791k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Srikrishna G, Panneerselvam K, Westphal V, Abraham V, Varki A, Freeze HH. Two proteins modulating transendothelial migration of leukocytes recognize novel carboxylated glycans on endothelial cells. J Immunol. 2001;166:4678–4688. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.7.4678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Robinson MJ, Tessier P, Poulsom R, Hogg N. The S100 family heterodimer, MRP-8/14, binds with high affinity to heparin and heparan sulfate glycosaminoglycans on endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:3658–3665. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102950200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thorey IS, Roth J, Regenbogen J, Halle JP, Bittner M, Vogl T, Kaesler S, Bugnon P, Reitmaier B, Durka S, Graf A, Wockner M, Rieger N, Konstantinow A, Wolf E, Goppelt A, Werner S. The Ca2+-binding proteins S100A8 and S100A9 are encoded by novel injury-regulated genes. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:35818–35825. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104871200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yui S, Nakatani Y, Mikami M. Calprotectin (S100A8/S100A9), an inflammatory protein complex from neutrophils with a broad apoptosis-inducing activity. Biol Pharm Bull. 2003;26:753–760. doi: 10.1248/bpb.26.753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aguiar-Passeti T, Postol E, Sorg C, Mariano M. Epithelioid cells from foreign-body granuloma selectively express the calcium-binding protein MRP-14, a novel down-regulatory molecule of macrophage activation. J Leukoc Biol. 1997;62:852–858. doi: 10.1002/jlb.62.6.852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yui S, Mikami M, Tsurumaki K, Yamazaki M. Growth-inhibitory and apoptosis-inducing activities of calprotectin derived from inflammatory exudate cells on normal fibroblasts: regulation by metal ions. J Leukoc Biol. 1997;61:50–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Isoda K, Folco EJ, Shimizu K, Libby P. AGE-BSA decreases ABCG1 expression and reduces macrophage cholesterol efflux to HDL. Atherosclerosis. 2007;192:298–304. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2006.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mues B, Brisse B, Zwadlo G, Themann H, Bender F, Sorg C. Phenotyping of macrophages with monoclonal antibodies in endomyocardial biopsies as a new approach to diagnosis of myocarditis. Eur Heart J. 1990;11:619–627. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a059767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Burkhardt K, Radespiel-Troger M, Rupprecht HD, Goppelt-Struebe M, Riess R, Renders L, Hauser IA, Kunzendorf U. An increase in myeloid-related protein serum levels precedes acute renal allograft rejection. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2001;12:1947–1957. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V1291947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Burkhardt K, Bosnecker A, Hillebrand G, Hofmann GO, Schneeberger H, Burmeister G, Land W, Gurland HJ. MRP8/14-positive macrophages as early acute cellular rejection markers, and soluble MRP8/14 and increased expression of adhesion molecules following renal transplantation. Transplant Proc. 1995;27:890–891. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hobbs JA, May R, Tanousis K, McNeill E, Mathies M, Gebhardt C, Henderson R, Robinson MJ, Hogg N. Myeloid cell function in MRP-14 (S100A9) null mice. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:2564–2576. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.7.2564-2576.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Manitz MP, Horst B, Seeliger S, Strey A, Skryabin BV, Gunzer M, Frings W, Schonlau F, Roth J, Sorg C, Nacken W. Loss of S100A9 (MRP14) results in reduced interleukin-8-induced CD11b surface expression, a polarized microfilament system, and diminished responsiveness to chemoattractants in vitro. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:1034–1043. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.3.1034-1043.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shimizu K, Schonbeck U, Mach F, Libby P, Mitchell RN. Host CD40 ligand deficiency induces long-term allograft survival and donor-specific tolerance in mouse cardiac transplantation but does not prevent graft arteriosclerosis. J Immunol. 2000;165:3506–3518. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.6.3506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shimizu K, Libby P, Shubiki R, Sakuma M, Wang Y, Asano K, Mitchell RN, Simon DI. Leukocyte integrin Mac-1 promotes acute cardiac allograft rejection. Circulation. 2008;117:1997–2008. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.724310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shimizu K, Shichiri M, Libby P, Lee RT, Mitchell RN. Th2-predominant inflammation and blockade of IFN-gamma signaling induce aneurysms in allografted aortas. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:300–308. doi: 10.1172/JCI19855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shimizu K, Aikawa M, Takayama K, Libby P, Mitchell RN. Direct anti-inflammatory mechanisms contribute to attenuation of experimental allograft arteriosclerosis by statins. Circulation. 2003;108:2113–2120. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000092949.67153.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Albert ML, Pearce SF, Francisco LM, Sauter B, Roy P, Silverstein RL, Bhardwaj N. Immature dendritic cells phagocytose apoptotic cells via alphavbeta5 and CD36, and cross-present antigens to cytotoxic T lymphocytes. J Exp Med. 1998;188:1359–1368. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.7.1359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lyons AB. Analysing cell division in vivo and in vitro using flow cytometric measurement of CFSE dye dilution. J Immunol Methods. 2000;243:147–154. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(00)00231-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shimizu K, Sugiyama S, Aikawa M, Fukumoto Y, Rabkin E, Libby P, Mitchell RN. Host bone-marrow cells are a source of donor intimal smooth- muscle-like cells in murine aortic transplant arteriopathy. Nat Med. 2001;7:738–741. doi: 10.1038/89121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shimizu K, Minami M, Shubiki R, Lopez-Ilasaca M, MacFarlane L, Asami Y, Li Y, Mitchell RN, Libby P. CC chemokine receptor-1 activates intimal smooth muscle-like cells in graft arterial disease. Circulation. 2009;120:1800–1813. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.859595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Leyva-Cobian F, Carrasco-Marin E. Participation of intracellular oxidative pathways in antigen processing by dendritic cells, B cells and macrophages. Immunol Lett. 1994;43:29–37. doi: 10.1016/0165-2478(94)00146-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kumar A, Steinkasserer A, Berchtold S. Interleukin-10 influences the expression of MRP8 and MRP14 in human dendritic cells. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2003;132:40–47. doi: 10.1159/000073263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Unanue ER. Antigen-presenting function of the macrophage. Annu Rev Immunol. 1984;2:395–428. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.02.040184.002143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cheng P, Corzo CA, Luetteke N, Yu B, Nagaraj S, Bui MM, Ortiz M, Nacken W, Sorg C, Vogl T, Roth J, Gabrilovich DI. Inhibition of dendritic cell differentiation and accumulation of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in cancer is regulated by S100A9 protein. J Exp Med. 2008;205:2235–2249. doi: 10.1084/jem.20080132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Grigorian M, Tulchinsky E, Burrone O, Tarabykina S, Georgiev G, Lukanidin E. Modulation of mts1 expression in mouse and human normal and tumor cells. Electrophoresis. 1994;15:463–468. doi: 10.1002/elps.1150150163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Du XJ, Cole TJ, Tenis N, Gao XM, Kontgen F, Kemp BE, Heierhorst J. Impaired cardiac contractility response to hemodynamic stress in S100A1-deficient mice. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:2821–2829. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.8.2821-2829.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Croce K, Gao H, Wang Y, Mooroka T, Sakuma M, Shi C, Sukhova GK, Packard RR, Hogg N, Libby P, Simon DI. Myeloid-related protein-8/14 is critical for the biological response to vascular injury. Circulation. 2009;120:427–436. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.814582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pagano RL, Sampaio SC, Juliano L, Juliano MA, Giorgi R. The C-terminus of murine S100A9 inhibits spreading and phagocytic activity of adherent peritoneal cells. Inflamm Res. 2005;54:204–210. doi: 10.1007/s00011-005-1344-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brun JG, Ulvestad E, Fagerhol MK, Jonsson R. Effects of human calprotectin (L1) on in vitro immunoglobulin synthesis. Scand J Immunol. 1994;40:675–680. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.1994.tb03523.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Swanson JA, Baer SC. Phagocytosis by zippers and triggers. Trends Cell Biol. 1995;5:89–93. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(00)88956-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Allen LA, Aderem A. Molecular definition of distinct cytoskeletal structures involved in complement- and Fc receptor-mediated phagocytosis in macrophages. J Exp Med. 1996;184:627–637. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.2.627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Buonocore S, Flamand V, Goldman M, Braun MY. Bone marrow-derived immature dendritic cells prime in vivo alloreactive T cells for interleukin-4-dependent rejection of major histocompatibility complex class II antigen-disparate cardiac allograft. Transplantation. 2003;75:407–413. doi: 10.1097/01.TP.0000044172.19087.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Le Moine A, Surquin M, Demoor FX, Noel JC, Nahori MA, Pretolani M, Flamand V, Braun MY, Goldman M, Abramowicz D. IL-5 mediates eosinophilic rejection of MHC class II-disparate skin allografts in mice. J Immunol. 1999;163:3778–3784. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xie A, Wang S, Zhang K, Wang G, Ye P, Li J, Chen W, Xia J. Treatment with interleukin-12/23p40 antibody attenuates acute cardiac allograft rejection. Transplantation. 2011;91:27–34. doi: 10.1097/tp.0b013e3181fdd948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Benghiat FS, Graca L, Braun MY, Detienne S, Moore F, Buonocore S, Flamand V, Waldmann H, Goldman M, Le Moine A. Critical influence of natural regulatory CD25+ T cells on the fate of allografts in the absence of immunosuppression. Transplantation. 2005;79:648–654. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000155179.61445.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Benghiat FS, Craciun L, De Wilde V, Dernies T, Kubjak C, Lhomme F, Goldman M, Le Moine A. IL-17 production elicited by allo-major histocompatibility complex class II recognition depends on CD25posCD4pos T cells. Transplantation. 2008;85:943–949. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31816a5ae7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vokaer B, Van Rompaey N, Lemaitre PH, Lhomme F, Kubjak C, Benghiat FS, Iwakura Y, Petein M, Field KA, Goldman M, Le Moine A, Charbonnier LM. Critical role of regulatory T cells in Th17-mediated minor antigen-disparate rejection. J Immunol. 2010;185:3417–3425. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mandelbrot DA, Oosterwegel MA, Shimizu K, Yamada A, Freeman GJ, Mitchell RN, Sayegh MH, Sharpe AH. B7-dependent T-cell costimulation in mice lacking CD28 and CTLA4. J Clin Invest. 2001;107:881–887. doi: 10.1172/JCI11710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Morelli AE, Thomson AW. Tolerogenic dendritic cells and the quest for transplant tolerance. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:610–621. doi: 10.1038/nri2132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Steinman RM. Lasker Basic Medical Research Award. Dendritic cells: versatile controllers of the immune system. Nat Med. 2007;13:1155–1159. doi: 10.1038/nm1643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wakkach A, Fournier N, Brun V, Breittmayer JP, Cottrez F, Groux H. Characterization of dendritic cells that induce tolerance and T regulatory 1 cell differentiation in vivo. Immunity. 2003;18:605–617. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00113-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Averill MM, Barnhart S, Becker L, Li X, Heinecke JW, Leboeuf RC, Hamerman JA, Sorg C, Kerkhoff C, Bornfeldt KE. S100A9 differentially modifies phenotypic states of neutrophils, macrophages, and dendritic cells: implications for atherosclerosis and adipose tissue inflammation. Circulation. 2011;123:1216–1226. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.985523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mathisen B, Lindstad RI, Hansen J, El-Gewely SA, Maelandsmo GM, Hovig E, Fodstad O, Loennechen T, Winberg JO. S100A4 regulates membrane induced activation of matrix metalloproteinase-2 in osteosarcoma cells. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2003;20:701–711. doi: 10.1023/b:clin.0000006819.21361.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bjornland K, Winberg JO, Odegaard OT, Hovig E, Loennechen T, Aasen AO, Fodstad O, Maelandsmo GM. S100A4 involvement in metastasis: deregulation of matrix metalloproteinases and tissue inhibitors of matrix metalloproteinases in osteosarcoma cells transfected with an anti-S100A4 ribozyme. Cancer Res. 1999;59:4702–4708. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Whiteman HJ, Weeks ME, Dowen SE, Barry S, Timms JF, Lemoine NR, Crnogorac-Jurcevic T. The role of S100P in the invasion of pancreatic cancer cells is mediated through cytoskeletal changes and regulation of cathepsin D. Cancer Res. 2007;67:8633–8642. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yong HY, Moon A. Roles of calcium-binding proteins, S100A8 and S100A9, in invasive phenotype of human gastric cancer cells. Arch Pharm Res. 2007;30:75–81. doi: 10.1007/BF02977781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hsing LC, Rudensky AY. The lysosomal cysteine proteases in MHC class II antigen presentation. Immunol Rev. 2005;207:229–241. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2005.00310.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.