Abstract

Integrins αvβ3 and αvβ6 are highly expressed on tumor cells and/or by the tumor vasculature of many human cancers, and represent promising targets for anti cancer therapy. Novel chemically programmed antibodies (cpAbs) targeting these integrins were prepared using the catalytic aldolase Antibody (Ab) programming strategy. The effects of the cpAbs on cellular functions related to tumor progression were examined in vitro using tumor cell lines and their cognate integrin ligands, fibronectin and osteopontin. The inhibitory functions of the conjugates and their specificity were examined based on interference with cell-cell and cell-ligand interactions related to tumor progression. Cell binding analyses of the anti-integrin cpAbs revealed high affinity for tumor cells that overexpressed αvβ3 and αvβ6 integrins, and weak interactions with αvβ1 and αvβ8 integrins, in vitro. Functional analyses demonstrated that the cpAbs strongly inhibited cell-cell interactions through osteopontin binding, and they had little or no immediate effects on cell viability and proliferation. Based on these characteristics, the cpAbs are likely to have a broad range of activities in vivo, as they can target and antagonize tumors and tumor vasculatures expressing one or multiple αv integrins. Presumably, these conjugates may inhibit the establishment of metastastatic tumors in distant organs through interfering with cell adhesion more effectively than antibodies or compounds targeting one integrin only. These anti-integrin cpAbs may also provide useful reagents to study combined effect of multiple αv integrins on cellular functions in vitro, on pathologies, including tumor angiogenesis, fibrosis, and epithelial cancers, in vivo

INTRODUCTION

Integrin adhesion receptors, expressed as heterodimers at the surface of all mammalian cells, regulate various cellular processes, including adhesion, migration, proliferation, differentiation and cell death.1–4 Integrins mediate cell-cell and cell-matrix attachment through interaction with their cognate ligands, and expression of these receptors in normal cells are well controlled. In contrast, under pathologic conditions such as cancer, expression levels of certain integrins are altered. Often, more than one heterodimeric integrin is overexpressed on cancer cells during disease progression, and inhibition of one specific integrin type does not necessarily affect the cellular function to be targeted as, in some cases, integrins can substitute for each other to influence a given cellular process.5 In cancer patients, overexpression of key integrins, such as αvβ3 and αvβ5 has been observed on tumor cells, especially on highly metastatic cells.6 In addition, certain host responses such as angiogenic endothelial cell sprouting rely on de novo expression of integrin αvβ3 in the tumor vasculature. Similarly, integrin αvβ6 is overexpressed especially on cells of many epithelial cancers, including squamous carcinoma of the breast, cervix, esophagus, head and neck, lung, ovaries and skin.7–14 Notably, these tumor cells were shown to express αvβ6 in 33–92% of the studied cases while the integrin is missing on the normal epithelial cells of these organs.7 The effects of upregulation of these αv integrins in the above cancers are manifold, but mechanisms of their involvement in disease progression and consequences of their inhibition are not fully understood. An important clinical aspect that is certain, however is that these integrins are associated with tumor angiogenesis, growth and metastasis.15 Therefore, these integrins are considered important targets for cancer therapy and diagnosis, and development of their inhibitors remains subject of intense research. Whereas selective inhibitors of various heterodimeric integrins are needed to examine their functions, broad acting inhibition of multiple key integrins in the clinic could be necessary to achieve effective cancer therapy.

Previously, we have reported the Aldolase antibody (Ab) programming technology that involves covalent conjugation of a compound, usually a small molecule, peptidomimetic or peptide, with an aldolase Ab, such as 38C2, and provides chemically-programmed Ab (cpAb).16–21 Conjugation takes place selectively in the Ab binding site, and is mediated by a designed linker usually possessing a β-diketone (DK),16–18 an acetone adduct of vinyl ketone (pVK) as a latent VK,19–20 or a lactam function.21 Importantly, the pVK compound undergoes retro aldol reaction to give a reactive VK linker, before the latter reacts with the Ab. We have also examined the programming of all available aldolase Abs, including 33F12, 38C2, 84G3, 84H9, 84G11, 85A2, 85C7, 85H6, 90G8, 92F9 and 93F3,22–23 using multiple integrin inhibitors. The results revealed that most Abs could be programmed yet the resultant cpAbs did not necessarily exhibit cell-targeting properties.20 Nonetheless, using the aldolase Ab-programming strategy, we have prepared numerous integrin-targeting cpAbs, including those directed to integrins αvβ3 and αvβ5. We anticipate that a library of cpAbs that can target various integrins can be developed in this manner, particularly those for which low molecular weight inhibitors are known. These cpAbs may find uses as chemical biology and drug discovery tools, whereas some may also possess therapeutic and diagnostic applications.24–26 In this article, we summarize the details of aldolase Ab programming using a dual inhibitor of integrins αvβ3 and αvβ6, and in vitro evaluation of the cell binding characteristics and functional properties of the resulting cpAbs.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

All chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Generation and purification of mouse mAbs 38C2, 84G3, 85H6, and 90G8 are described elsewhere.22–23 Human cancer cell lines: M21 and M21-L melanoma,27 BMS and BCM1 breast cancer,28 UCLA-P3 lung carcinoma,29 SJSA1-Lung, a lung metastasis derived osteosarcoma,30 and OVCA 429 and OVCA 433 ovarian carcinoma31 are available or generated in this laboratory. SW480 puro, SW480-β3, SW480-β6 and SW480-β8 cells, and anti-αvβ8 integrin 14E5 mouse Ab were kindly provided by Dr. Stephen Nishimura of UCSF Medical Center, San Francisco, California.32–33 Antibody L230 (anti-αv, ATCC Cat. No. HB8448) was a gift from the Pfizer, Inc. Antibodies M21–3 (anti-β3), and P1F6 (anti-αVβ5) and P5D2 (anti-β1) (hybridoma cells gifted by Elizabeth Wayner) were prepared in house in Felding-Habermann laboratory. Antibodies BHA2.1 (anti-α2β1, Cat. No. MAB1998) and 10D5 (anti-αVβ6, Cat. No. MAB2077Z) were purchased from Millipore, Billerica, MA. FITC conjugated anti-mouse Ab was purchased from Jackson Laboratories, and APC conjugated anti-mouse Ab was purchased from Invitrogen, California. Human fibronectin (Cat. No. 341635) was purchased from EMD Biosciences. Human osteopontin (OPN) was cloned from SJSA1 human osteosarcoma cells, expressed as a His-tagged protein in E coli, and purified under non-denaturing conditions on Ni-NTA agarose.

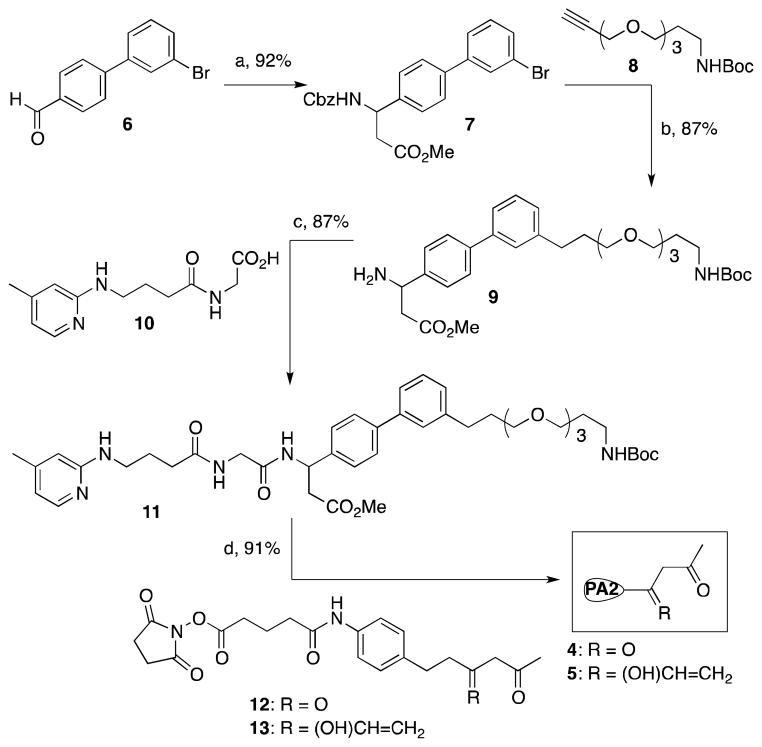

Synthesis of compounds 4 and 5 (See Scheme 1)

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of integrin αvβ3/αvβ6 antagonists coupled with a DK and p-VK linker for production of the cpAbs, (PA2, Programming agent). Key: (a) (i) NH4OH, malonic acid, EtOH, reflux, 24 h, (ii) MeOH, SOCl2, reflux, 4 h, (iii) CbzCl, aq. Na2CO3, EtOAc, 0 °C - RT, 16 h, (b) (i) Pd(PPh3)2Cl2, CuI, NEt3, CH3CN, 24 h, (ii) H2, Pd-C, 0.1 M HCl, MeOH, 24 h, (c) EDC, HOBt, DIPEA, DMF, 0 °C - RT, 16 h, (d) (i) 2M Aq. NaOH, MeOH, RT, 16 h, (ii) TFA, anisole, CH2Cl2, RT, 16 h, (iii) 12, or 13, Et3N, CH3CN, RT, 2 h.

Compound 7

Malonic acid (446 mg, 4.28 mmol) and ammonium acetate (660 mg, 8.56) were added sequentially to a stirring solution of 3′-bromo-[1,1′-biphenyl]-4-carbaldehyde (6, 2g, 4.28 mmol) in EtOH (30 mL).34–35 After the mixture was refluxed for 24 h, it was cooled to room temperature and filtered using EtOH and ether to give the corresponding β amino acid as white solids. The latter product was taken to next step without further purification

The above-described beta amino acid was suspended in 100 mL MeOH, and SOCl2 (1.6 mL, 21.4 mmol) was added drop-wise to the suspension at −5 °C. After all SOCl2 was added, the mixture was refluxed for 4 h and solvents were removed. The residue was taken in EtOAc (50 mL) and aqueous NaHCO3 (50 mL), and CbzCl (0.9 mL, 6.42 mmol) was added drop-wise to the mixture at 0 °C. After the mixture was stirred overnight, it was worked-up using EtOAc and water. The combined organic layer was washed with brine, dried over Na2SO4, purified by column chromatography to give pure Cbz-protected amino ester 7 (3.3 g, Yield 92% from 6). 1HNMR (CDCl3, 500 MHz): δ 7.69 (s, 1H), 7.51-7.37 (m, 4H), 7.32-7.11 (m, 8H), 6.03 (d, 1H, J = 2.7 Hz), 5.21 (m, 1H), 5.16-5.05 (m, 2H), 3.62 (s, 3H), 2.96-2.73 (m, 2H). HRMS-ESI: Calc. for C24H22BrNO4, 467.07, Found 467.072.

Compound 9

PdCl2(PPh3)2 (495 mg, 0.7 mmol) and CuI (268 mg, 1.4 mmol) were added to a degassed solution of the β amino ester 7 (3.3 g, 7.1 mmol) and NEt3 (2 mL) in CH3CN (30 mL), and the reaction mixture was heated to the reflux temperature.36 A solution of alkyne 8 (2.25 g, 10.6 mmol) in degassed CH3CN (30 mL) was added dropwise to the reaction mixture over one hour, and heating was continued for 24 h. After the reaction was complete, as judged by TLC, the mixture was diluted with EtOAC, washed with NH4Cl and brine, and dried over Na2SO4. Solvents were removed under vaccuo and the residue was chromatographed over silica get giving the pure coupled product (3.7 g, 87% yield). 1HNMR (300 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.64 (s, 1H), 7.53-7.45 (m, 4H), 7.41-7.29 (m, 8H), 5.93 (d, 1H, J = 2.7 Hz), 5.22 (m, 1H), 5.17-5.01 (m, 3H), 4.42 (s, 2H), 3.62-3.57 (m, 2H), 3.42-3.39 (m, 2H), 3.37-3.24 (m, 2H), 3.63 (s, 3H), 3.62-3.59 (s, 2H), 3.57-3.49 (m, 2H), 3.49-3.31 (m, 2H), 2.95-2.87 (m, 2H), 1.79-1.68 (m, 2H), 1.48 (s, 9H), HRMS-ESI: Calc. for C35H40N2O7, 601.28 (M+H)+, Found 601.276.

Pd-C (10% w/w, 500 mg) was added to a solution of the above-described coupled product (3.7 g, 6.2 mmol) in EtOH (20 mL) and the mixture was stirred under hydrogen atmosphere for 24h. The mixture was filtered to remove insoluble materials, solvents removed under vacuum, and the resultant product 9 (2.89 g) was taken to next reaction without further purification

Compound 10

EDC (3.79 g, 19.8 mmol) and DIPEA (9.5 ml, 54 mmol) were added successively to a mixture of Gly-OMe hydrochloride salt (2.47 g, 19.8 mmol), 4-(pyridine-2-ylamino)butanoic acid (3.5 g, 18 mmol), and HOBt (2.68 g, 19.8 mmol) in DMF (40 mL) at 0 °C, and the mixture was stirred at room temperature overnight. The mixture was concentrated, and worked-up using EtOAc-aq. NH4Cl, saturated NaHCO3, and brine. The organic layer was dried over Na2SO4, and purified giving the methyl ester of compound 10 (4.1 g, 87% yield). 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.87 (d, 1H, J = 2.7 Hz), 7.61 (t, 1H, J = 3.1 Hz), 6.39 (d, 1H, J = 2.7 Hz), 6.21 (s, 2H), 4.99 (t, 1H, J = 2.9 Hz), 4.07 (d, 2H, J = 3.7 Hz), 3.71 (s, 3H), 3.41-3.31 (m, 2H), 2.36 (t, 2H, J = 7.1 Hz), 2.39 (s, 3H), 2.83 (q, 2H, J = 7.1 Hz).

A solution of 2M aq. NaOH (22.6 ml, 45.2 mmol) was added to a solution of the above-described ester (4 g, 15.1 mmol) in dioxane (50 mL), and the mixture was stirred at room temperature overnight. When the starting material had disappeared the reaction mixture was acidified to pH 2 and the solvent was evaporated to give the corresponding free acid 10 (3.8 g) that was taken to next step without further purification

Compound 11

EDC (1.3 g, 6.8 mmol), HOBt (915 mg, 6.78 mmol) and NMM (3.4 mL, 30.8 mmol) were added sequentially to a solution of the above-described free amine 9 (2.89 g, 6.2 mmol) and acid 10 (3.09 g, 12.3 mmol) in DMF (30 mL) at 0 °C, and the reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature overnight. Solvents were removed under vaccuo, and the residue was dissolved in EtOAC, and washed with saturated NaHCO3, NH4Cl, followed by brine. The organic layer was dried over Na2SO4, solvents were removed and the residue was purified by column chromatography to give compound 11 (3.76 g, 87% yield based on amine). 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3): δ 8.01-7.97 (m, 2H), 7.62-7.47 (m, 6H), 7.44-7.29 (m, 5H), 7.12 (d, 1H, J = 5.1 Hz), 6.39 (m, 1H), 6.17 (bs, 1H), 5.47 (m, 1H), 5.07 (bs, 1H), 4.77 (t, 1H, J = 3.7 Hz), 4.01-3.98 (m, 2H), 3.72 (s, 1H), 3.68-3.61 (m, 5H), 3.62 (s, 3H), 3.61-3.54 (m, 4H), 3.53-3.47 (m, 4H), 3.42-3.31 (m, 3H), 3.23-3.18 (m, 2H), 2.97-2.86 (m, 2H), 2.77-2.73 (m, 2H), 2.37 (t, 3H, J = 7.1 Hz), 2.21-2.17 (m, 2H), 2.14 (s, 3H). HRMS- ESI: Calc. for C39H53N5O7, 704.39 (M+H)+, Found 704.388.

Compounds 4 and 5

A solution of 2M aq. NaOH (1.06 mL, 2.12 mmol) was added to a solution of the above-described ester (500 mg, 0.70 mmol) in dioxane (2 mL), and the mixture was stirred at room temperature for overnight. When the starting material had disappeared the reaction mixture was acidified to pH 2.0 and the solvent was evaporated to give the corresponding free acid quantitatively which was taken to next step without further purification.

The above-described crude acid was treated with 25% TFA/CH2Cl2 (v/v, 1 mL, 1 drop of anisole) at room temperature overnight, then the solvent was removed under vacuum and used for next reaction without further purification.

To a solution of the above-described amino acid (100 mg, 0.17 mmol) in CH3CN (1 mL) was added NEt3 (0.09 mL, 0.51 mmol) followed by the NHS ester 1217,37 (127 mg, 0.34 mmol), and the mixture was stirred at room temperature for 2 h. Solvents were removed under vaccuo and the residue was purified by column chromatography to give the title product 4 (151 mg, 91% yield). 1H NMR (300 MHz, CDCl3 + CD3OD): δ 7.92-7.77 (m, 1H), 7.57-7.26 (m, 10H, 7.20-7.07 (m, 3H), 6.61 (s, 1H), 6.47 (d, 1H, J = 2.3 Hz), 5.28 (t, 1H, J = 2.7 Hz), 4.10-4.03 (m, 1H), 3.83-3.75 (m, 1H), 3.68-3.55 (m, 8H), 3.52-3.43 (m, 5H), 3.35-3.28 (m, 2H), 3.27-3.13 (m, 4H), 2.94-2.79 (m, 4H), 2.77-2.65 (m, 3H), 2.64-2.46 (m, 3H), 2.44-2.33 (m, 2H), 2.27-2.16 (m, 4H), 2.16-2.13 (6H), 2.09-1.86 (m, 2H), 1.81-1.69 (m, 3H), 1.31 (t, 3H, J = 6.9 Hz). HRMS-ESI: Calc. for (C54H70N6O11), 979.5175 (M+H)+, Found 979.5171

Similarly, to the above-described amino acid (100 mg, 0.17 mmol) was reacted with NHS ester 13 (9,25) (127 mg, 0.34 mmol) giving 5 (155 mg, 91% yield). 1H NMR (CD3OD+CDCl3, 600MHz): δ 7.58 (bs, 1H), 7.53 (s, 1H), 7.49-7.41 (m, 4H), 7.38 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 2H), 7.35-7.29 (m, 4H), 7.15 (bd, J = 6.0 Hz, 1H), 7.11 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 6.53(bs, 1H), 6.46(bs, 1H), 5.91(dd, J = 17.4, 10.8 Hz, 1H), 5.30 (d, J = 16.8 Hz, 1H), 5.26 (bs, 1H), 5.18 (d, J = 10.8 Hz, 1H), 4.11 (d, J = 17.4 Hz, 1H), 3.8 (d, J = 17.4 Hz, 1H), 3.70-3.63 (m, 6H), 3.63-3.57 (m, 4H), 3.55-3.49 (m, 4H), 3.36-3.30 (m, 3H), 3.28 (t, J = 6.6 Hz, 2H), 2.78 (s, 1H), 2.76-2.68 (m, 4H), 2.65-2.50 (m, 4H), 2.37 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 2.29-2.24 (m, 4H), 2.19 (s, 3H), 2.12-2.02 (m, 2H), 2.00-1.90 (m, 4H), 1.88-1.82 (m, 1H), 1.80-1.74 (m, 2H), 1.30-1.25 (m, 6H). MS-ESI (m/z): 1007 (M+), 1008 (M+H)+, 1030 (M+Na)+.

Formation of the programmed antibodies (cpAbs) – General Method.37

Compounds 1–2 or 4–5 (100 μM in CH3CN, 2.5–3 μl) were added separately to Aldolase Abs (1 μM, 100 μl) in Eppendorf tubes at pH 6.0, 7.4 and 8.5, and the mixtures were incubated at room temperature for 0.5 hrs (for the DK compounds 1 and 4), or 37 °C for 1.5 hrs (for the pVK compounds 2 and 5). Mixture of the antibodies (1 μM, 100 μl) and CH3CN (3 μl) was incubated at 37 °C (1.5 hrs) and used as the control group. Subsequently, the mixtures were transferred to the 96 well fluorescence reader plate, and a solution of methodol (10 mM in EtOH, 2 μl) was added to each well containing the Ab or the resulting cpAbs, and progress of the retro aldol reaction of methodol giving fluorescent 6-methoxy-2-naphthaldehyde was measured using a fluorometer,37,39 λabs 330 nm and λem 452 nm. Inhibition of the retro aldol reaction was used as the measurement of the Ab programming using compounds 1–2 and 4–5. Similarly, the cpAbs 38C2-4,5, 84G3-4,5, 85H6-4,5, and 90G8-4,5, were prepared by mixing a solution of compounds 4 (125 μM in DMSO, 6.7 μL) or 5 (150 μM in DMSO, 6.7 μL) with Abs 38C2, 84G3, 85H6 or 90G8 (50 μM, 6.7 μL), as needed, in PBS buffer (pH 7.4, total volume 100 μL) and incubating the mixtures at room temperature for 0.5 hrs (for compound 4) or at 37 °C for 1.5–36 hrs (for compound 5).

Evaluation of the binding of the cpAbs to αvβ3,α vβ5, and αvβ6 integrin-expressing cells

Flow cytometry

Cells were detached by brief trypsinization with 0.25% (w/v) trypsin, 1 mM EDTA, washed with PBS, and resuspended at 2×106 cells/mL in ice cold flow cytometry buffer (for anti integrin binding: 1% BSA in TBS pH 7.4; for chemically programmed Abs (cpAbs): 1% BSA, 100 μM MnCl2, TBS pH 7.4). Aliquots of 50 μL containing 105 cells were distributed into tubes for indirect immunofluorescence staining in the presence of 20 μg/mL of cpAbs or 10 μg/mL of anti-integrin mAbs. After incubation for 45 mins on ice and washing, cells were incubated with FITC or APC conjugated goat anti-mouse polyclonal antibodies (at a 1:100 dilution, i.e., 10 μg/mL in FACS buffer) for 45 min on ice. After a final wash, cells were analyzed using flow cytometry using a FACScalibur (Becton-Dickinson) as described earlier.20 All binding experiments were repeated at least three times at different time points using independent cell batches to determine the consistency of the results. Representative analyses are shown.

Cell-adhesion assay

To measure the effects of cpAbs on integrin mediated tumor cell adhesion, non-tissue culture treated 96- well plates were coated with human fibronectin or osteopontin (2 μg/ml in PBS) over night at 4 °C. The plates were washed and blocked with 2% BSA in TBS for 1h at RT. Tumor cells were harvested with Versene, and washed in serum free EMEM medium containing 0.5% BSA which was also used as adhesion buffer. Before plating onto the matrix proteins, the cells were preincubated with cpAbs at 2 μM final concentration with or without function blocking monoclonal anti-integrin antibodies at 100 μg/ml for 15 min at RT. The cells were then seeded at 2×104/well in the presence of the antibodies. Adhesion time was 20 min on fibronectin and 30 on osteopontin. To harvest attached cells, the non-adhered cells were removed by adding floatation medium (0.9% NaCl, 80% Percoll) which sinks to the bottom and gently lifts unbound cells, followed by fixation of the adhered cells with 3.3% glutaraldehyde and 20% Percoll. The attached cells were stained with cystal violet, washed, lyzed with 0.5% Triton × 100 in water and quantified by measuring optical absorbance at 595 nm. All cell adhesion experiments were carried out in triplicates.

Cell-survival assay

To measure effects of cpAbs on tumor cell viability and proliferation, 5×104 cells were plated into 24 well plates and incubated with or without cpAbs at 0.4 and 2 μM concentration. On days 1, 2, 3 and 4, cells were harvested and counted. Live cells were identified and counted based on trypan blue exclusion. Cell-survival assay was carried out once, and there were no replicates.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Programming of Ab 38C2 was earlier achieved using numerous low molecular weight inhibitors of integrin αvβ3, including compounds 1–2, which possessed a DK or a pVK (an aldol adduct of the VK) linker (Figure 1).17,19 Both DK compounds and the VK compounds reacted in the Ab binding sites was evident from the fact that the conjugates were catalytically inactive. We further anticipated that the ε amine function of the reactive lysine residue (pK < 6.0) residing in the hydrophobic environment in Ab binding sites reacted with both the DK and VK compounds giving an enaminone and the β-aminoketone derivative, respectively. Indeed, formation of the enaminone function was confirmed using UV spectroscopically that shows a characteristic λmax at 318 nm,22 and subsequently using the X-ray crystallographic study of the Ab 33F12 Fab that was reacted with the diketone hapten.38 On the other hand, the proposed mode of conjugation of the highly reactive VK compounds through the ε amine function of the reactive lysine residue of an aldolase Ab19–20 remained to be confirmed. In any case, it was certain that the VK compound also reacted in the Ab binding sites. Thus, most Abs, including 38C2, 84G3, 85H6, and 90G8, which possessed appreciable activity and catalyzed the retro aldol reaction of the pVK linker were programmed efficiently with compound 2.20

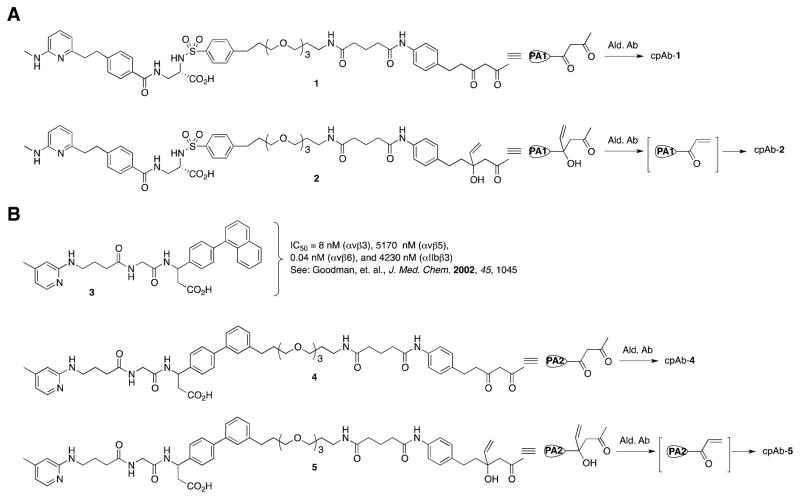

Figure 1.

(A) Potent αvβ3 and (B) αvβ3/αvβ6 integrin inhibitors with and without DK and p-VK linkers, and their conjugation to an aldolase Ab showing the Ab-programming strategy. PA1 and PA2, Programming Agents (compounds).

Chemical programming of the aldolase Abs is determined using the methodol assay, in that methodol is used as a substrate that undergoes a retro aldol reaction catalyzed by all of the above-described aldolase Abs to produce fluorescent 6-methoxy-2-naphthaldehyde.37,39 In contrast, a programmed Ab is no longer active and does not catalyze the retro aldol reaction of methodol, and therefore no fluorescence is detected. Thus, we found that the programming of all Abs was complete in less than 0.5 hr (room temperature) using the DK compound 1, and was over 95–98% complete upon 2–24 hrs incubation (37 °C) with the pVK compound 2, at pH 7.4 (Figure 2, also see Supporting Information (SI) Figure S-1). We further confirmed that the Ab-programming using compounds 1 and 2 is best achieved at pH 7.4, though most Abs, including Ab 38C2, can also be programmed at pH 6.0 and 8.5. On the other hand, all Abs, except 38C2, 84G3 and 93F3, possessed reduced catalytic activity at pH 6.0 as compared to that at pH 7.4, which we analyzed using the methodol assay. Apparently, the catalytic ω amine of the lysine residue in these Abs, but not in 38C2, 84G3 and 93F3, was already protonated at pH 6.0.

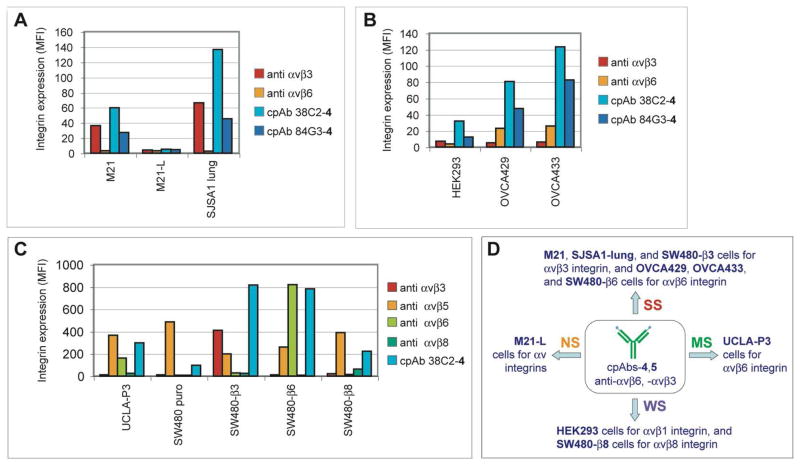

Figure 2.

Binding specificity of cpAbs 38C2-4 and 84G3-4, to αv integrins expressed by human tumor cells. Flow cytometry analysis showing the level of cpAb binding to various tumor cells, including (A) M21, M21-L, and SJSA1-lung, (B) HEK293, OVCA429, and OVCA433, and (C) UCLA-P3, SW480 puro, SW480-β3, SW480-β6, and SW480-β8, expressing/deficient in various integrins. ‘Anti-integrin’ denotes monoclonal anti-integrin complex specific antibodies used to report integrin expression. FITC labeled anti-mouse Abs were used to detect the binding of the Abs and cpAbs in A and B, and APC labeled anti-mouse Abs were used in C. (D) Schematic summary of the major integrin heterodimer recognzed by the cpAbs (SS, Strong staining; MS, moderate staining; WS, Weak staining; and NS, No apparent staining observed or interpreted due to specific integrin heterodimers).

To prepare novel αvβ3 and αvβ6 integrin directed cpAbs, we used the aldolase Abs 38C2, 84G3, 85H6 and 90G8, and compounds 4 and 5, which are analogs of the highly potent dual inhibitor of integrins αvβ3 and αvβ6, viz compound 3.40 The latter binds strongly to integrins αvβ3 (IC50 = 8 nM) and αvβ6 (IC50 = 0.04 nM), and weakly to αvβ5 (IC50 = 5170 nM) and αIIbβ3 (IC50 = 4230 nM). The inhibitory activity of compound 3 has been determined using immobilized integrins as the target; biotinylated human serum vitronectin have been used as ligands for integrins αvβ3 and αvβ5, fibronectin for αvβ6, and fibrinogen for αIIbβ3.40 The site of the linker arm in compounds 4 and 5, that connects the targeting agent 3 to Ab, was determined on the basis of a series of compounds, including 1 and 2, which were used earlier in Ab programming.17,19–20 Based upon the selectivity of compound 3, described above, we anticipated that the new cpAbs prepared with compounds 4 or 5 and the aldolase Abs should also bind efficiently to integrin αvβ6 and somewhat less efficiently to αvβ3, but not to integrins αvβ5 and αIIbβ3.40

Compounds 4 and 5 were prepared by modifying the synthesis of compound 3 using the readily available aldehyde 641 and acid 10, as shown in Scheme 1. Thus, aldehyde 6 was prepared by Suzuki reaction36 of 4-formylphenylboronic acid with 3-bromo-1-iodobenzene and subsequently converted to β-amino acid ester 7 by using Rodionov-Johnson reaction34–35 with malonic acid and ammonium hydroxide in refluxing ethanol, followed by protection of the free carboxylic acid function. Compound 7 was then reacted with alkyne 8 using Pd(PPh3)2Cl2 as catalyst to give a coupled alkyne product that was hydrogenated over Pd-C giving 9. The latter product underwent peptide coupling with acid 10 giving compound 11. Methyl ester and Boc function in compound 11 deprotected, and the resulting amino acid was reacted with the DK-NHS ester, 12, and VK-NHS ester, 13, yielding target compounds 4 and 5, respectively.

Subsequently, Abs 38C2, 84G3, 85H6, and 90G8 were programmed by incubating the individual Abs with compounds 4 or 5. As expected, complete programming of all Abs using compound 4 took place in 0.5 h at room temperature by using 2.2–2.5 molar equivalents of the compound. Similarly, they were 95–98% programmed using 2.5–3.0 molar equivalents of compound 5 in 2–16 hrs at 37 °C. Completion of the programming was determined using the methodol assay (see SI Figure S-2) and/or MALDI-TOF analysis.

To investigate whether compound 4 or 5 can redirect the Abs to integrins αvβ3 and αvβ6, we used the above-mentioned cpAbs prepared with Abs 38C2 or 84G3, i.e. 38C2-4 or 5, 84G3-4 or 5, and determined the cell binding properties and integrin specificity of these conjugates by using a series of human cancer cells lines, including M21 and M21-L melanoma,27 OVCA 429 and OVCA 433 ovarian carcinoma cells,31 BMS and BCM1 breast cancer,28 SJSA1-lung osteosarcoma,30 and HEK293 cells.42 The expression levels of target and control integrins on these tumor cells were analyzed by flow cytometry with monoclonal antibodies against αvβ3 (VNR1), αvβ5 ((P1F6), αvβ6 (10D5), α2β1 (BHA2.1), α5 (P1D6), β1 (P5D2), αv (L230), and β3 (M21.3.3). As shown in Figure 2A and SI Figure S-3A, M21 and SJSA1 lung cells have high expression levels of integrin αvβ3, and low levels of integrins αvβ5 and αvβ6. Similar results were found for BMS and BCM1 breast carcinoma cells (not shown). In contrast, OVCA 429 and OVCA 433 cells overexpress αvβ6, and do not or weakly express αvβ3 and αvβ5 (Figure 2B and SI Figure S-3A), and HEK293 cells lack both αvβ3 and αvβ6 (Figure 2B), but express αvβ1 integrin.42 M21-L cells lack αv integrin expression and were used as a control.27 All of the used cells express high levels of β1 integrins. Based on this information, our cell model includes cancer cells that overexpress - or lack - our target integrins αvβ3 and/or αvβ6, and either carry or lack other relevant integrins such as αvβ1 and αvβ5, and other major integrins not recognized or weakly recognized by our targeting agents.

Using this cell model, we determined binding and specificity of cpAbs 38C2-4, 38C2-5 and 84G3-4 by flow cytometry (Figures 2A, 2B and SI Figure S-3C). Evidently, cpAb 38C2-4 and 84G3-4 bind to M21, SJSA1 lung, HEK293, and OVCA429 and 433 cells that either express αvβ3, αvβ1 or αvβ6. CpAbs 38C2-4 and 84G3-4 did not bind to M21-L cells (Figures 2A and 2B) confirming that these cpAbs do not recognize any non-αv integrin, and therefore are αv integrin specific. Similarly, cpAb 38C2-5, which possessed the targeting moiety identical to 38C2-4, but differed in the linker (DK for 4 and pVK for 5), bound to M21, BMS, and BCM1 cells (See SI Figure S-3C). Interestingly, binding of 38C2-4 to target tumor cells is superior to that of 84G3-4, but we anticipate that the latter’s binding could also be improved through the linker length optimization. Nonetheless, these findings clearly show that the cpAbs prepared from Abs 38C2 or 84G3 and compounds 4 or 5 were capable of binding strongly to tumor cells that express either integrin αvβ3 and/or αvβ6, but not to those that lack αv integrin.

To determine specificities and cross-reactivities of the cpAbs among all the av integrins, next we used cpAb 38C2-4 and determined its binding to SW480 (wild type as well as those transfected with β3, β6 or β8 integrin) colon cancer,32 and UCLA-P3 lung carcinoma cells.29 Whereas UCLA-P3 cells express αvβ5 and αvβ6, and lack αvβ3 integrin, all SW480 cells express αvβ5, and SW480-β3, SW480-β6 and SW480-β8 cells also express αvβ3, αvβ6 and αvβ8 integrin, respectively, besides αvβ5 and α5β1 integrins. Again, we confirmed the expression levels of various integrins in these cells by flow cytometry and using the appropriate Abs (See Figure 2C and SI: Figure S-3). As expected, cpAb 38C2-4 bound strongly to SW480-β 3 and SW480-β6, but only weakly to SW480 (puro). Interestingly, however, 38C2-4 also bound to SW480-β8 cells, which express αvβ8 integrin. Based on all the findings, we conclude that all cpAbs, prepared with the aldolase Abs 38C2 or 84G3 and compounds 4 or 5, have strong affinity for both αvβ3 and αvβ6 integrins, and a weak affinity for the αvβ1 and αvβ8 integrins. These cpAbs are unlikely to have any appreciable affinity to αvβ5 integrin, because the binding affinity of the parent compound 3 to αvβ5 integrin is over 500 and 100,000 times weaker than to αvβ3 and αvβ6 integrins.40 The observed weak binding of the cpAb 38C2-4 to SW480 puro cells (Figure 2C) could be due to the αvβ1 integrin; it should be noted that all SW480 cells have high level of αv and β1 integrins (SI Figure 3B) besides the αvβ5 integrin.

Therapeutic applicability of the above-described dual αvβ3 and αvβ6 integrin-targeting cpAbs, including 38C2-4 and 84G3-4, as antitumor and antiangionenic agents would depend upon their ability to interfere with the functions of these integrins on cancer and endothelial cells. A key function in tumor progression and angiogenesis is cell adhesion to natural integrin ligands within the extracellular matrix.1–3 Most integrin binding matrix proteins are recognized by more than one integrin and the cognate receptors cooperate to mediate cell adhesion. To specifically address cpAbs’ effects on tumor cell adhesion mediated by integrins, we used fibronectin (FN) and osteopontin (OPN) as matrix ligands that are recognized by a number of integrins, including αvβ3 and αvβ6, overexpressed on tumor cells.43 The cell-ligand adhesion studies were carried out, in vitro, using M21 human melanoma and SJSA1 osteosarcoma cells. Both of these cell types are aggressively metastatic and both ligands are highly relevant for tumor cell adhesion, migration and invasion during tumor progression. Cell adhesion assays with the cpAbs 38C2-4 and 84G3-4 were conducted both in the presence and absence of known function blocking anti-integrin Abs, in order to assess the effects that the cpAbs would cause on individual integrins. In some experiments, we also examined cpAbs 85H6-4 and 90G8-4, which were prepared using compound 4 and Abs 85H6 and 90G8, respectively (See SI Figure S-5).

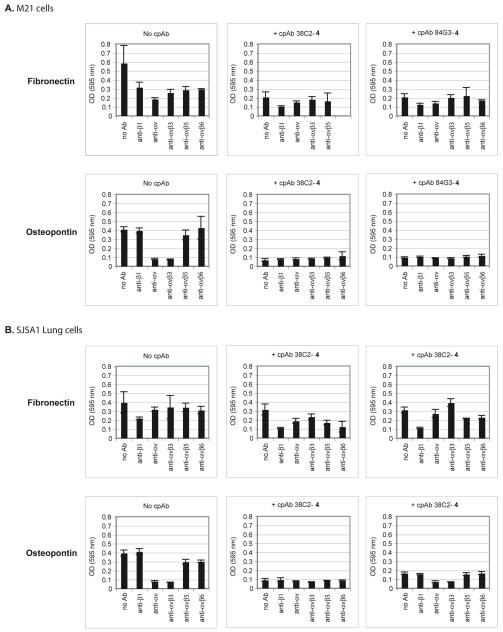

Before interrogating the effects of the cpAbs on tumor cell-FN and OPN ligands interactions, we defined the tumor cell adhesion model and determined the time course of cell adhesion and the best interception time for function blocking antibodies. For this, effects of various function blocking anti-integrin Abs, including anti-β1, anti-αv, anti-αvβ3, and anti-αvβ5 were examined on adhesion of M21 and SJSA1 lung cancer cells to FN and OPN as substrates. The results are shown in Figures 3A and 3B (Upper and Lower-Left) (and SI Figures S-4, S-5, and S-6). Evidently, integrin αvβ3 was the main integrin that mediated the adhesion of these cells to OPN, whereas the cell adhesion to FN is mediated by multiple αv and β1 integrins. While the expression levels of αvβ5 and αvβ6 are low (Figure 2A and SI Figure 3D), it is possible that these integrins engage in binding cooperating with other fibronectin receptors. This may explain the partial inhibition by anti αvβ5 and αvβ6 directed Abs of M21 cell adhesion (Figures 3A-Upper and 3B-Upper).

Figure 3.

Effect of function-blocking control Abs and aldolase Ab-derived cpAbs on adhesion of (A) M21 cells, and (B) SJSA1 Lung cells to fibronectin (FN) or osteopontin (OPN). Use of function blocking monoclonal anti-β1, -αv, -β3, αvβ3, αvβ5, and αvβ6 antibodies indicates that adhesion of (A, Upper Left) M21 cells or (B, Upper-Left) SJSA1 Lung cells to FN is substantialy inhibited by most Abs used, but to OPN can be inhibited mainly by anti-av and anti-avb3 integrin Abs for both (A, Lower Left) M21 cells and (B, Lower-Left) SJSA1 Lung cells and to some extent using anti-αvβ5 Ab for M21 cells, and anti-αvβ5, and anti-αvβ6 Abs for SJSA1 Lung cells. Use of cpAb 38C2-4 or 84G3-4 also moderately inhibits adhesion of (A, Upper-Middle and Upper Right) M21 cells and (B, Upper-Middle and Upper Right) SJSA1-Lung cells to FN, which may be further enhanced with the addition of most Abs used. In contrast, a use of cpAb 38C2-4 or 84G3-4 causes a substantial inhibition of (A, Lower-Middle and Lower Right) M21 cells and (B, Lower -Middle and Lower Right) and SJSA1-Lung cells to OPN, and remains unaffected when combined with all other Abs used.

Next, we evaluated the effects of the cpAbs on adhesion of M21 melanoma and SJSA1-lung carcinoma cells to FN and OPN. As shown in Figures 3A and 3B (Upper and Lower: Middle and Right), all cpAbs inhibited adhesion of both M21 and SJSA1-lung cells to FN and OPN. By combining anti-β1, anti-αv, anti-αvβ3, anti-αvβ5, or anti-αvβ6 Abs (100 μg/ml) with our aldolase Ab-based cpAbs in the adhesion experiments, and the results of our FACS assays described earlier in Figure 2, we can confidently state that our cpAbs inhibited adhesion of M21 and SJSA1 cells to both OPN and FN through specific interference with integrin αvβ3, and to some extent through αvβ1. The unconjugated aldolase Abs had no effect on the adhesion of any of our tumor cell models. Together, these data demonstrate a high efficacy of the cpAbs for interfering with multiple αv integrins mediated tumor cell adhesive functions

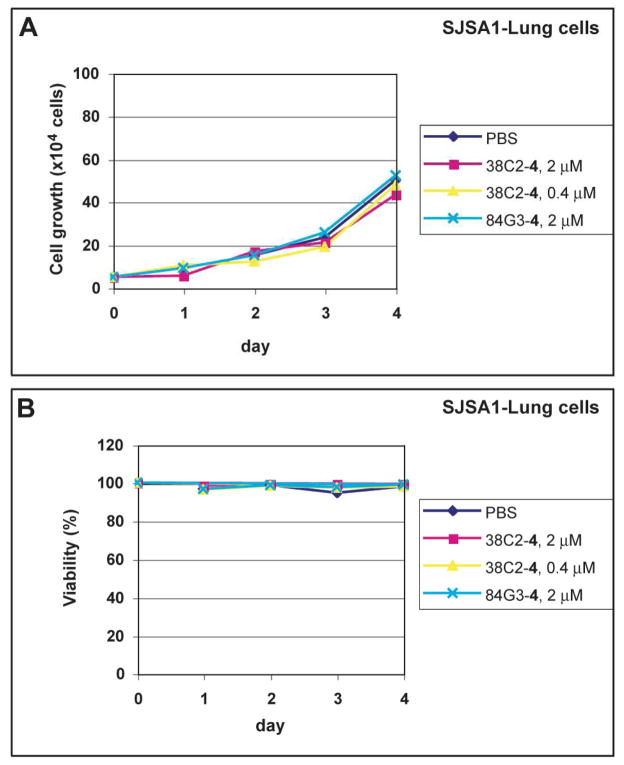

Integrin αvβ3-targeting cpAbs were previously shown to discern their therapeutic efficacies by causing both antitumor and/or antiangiogenic effects in vivo.16,19,24 To assess whether such effects could be mediated, at least in part, through direct cytotoxic or cytostatic impact of the antibody conjugates, we examined tumor cell viability in the presence of the cpAbs. In a Pilot Study, we found that these integrin targeting cpAbs cause no or only very low toxicity or cytostatic effects to the tumor cells. This was measured based on cell growth and viability in vitro. As shown in Figure 4, essentially no changes were observed in growth and viability of SJSA1 cells in the presence of the cpAbs. Generally more than 90% cells were found viable in each study. This observation is in close agreement with our prior studies using an anti-αvβ3 integrin cpAb, which also had little toxicity at 2 μM concentration, except on MAEC mouse endothelial cell line (IC50 ~ 1 μM).16 The results suggest that the anti-αvβ3 and dual αvβ3,αvβ6 integrin directed cpAbs may suppress tumor growth, presumably through interfering with the cell functions that control cell division and involve integrin mediated matrix contact survival signals. However, the cpAbs targeting multiple αv integrins per se do not mediate cell-killing at least at a low micromolar concentration.

Figure 4.

Viability and proliferation of SJSA1 cells in the absence and presence of 38C2-4 (0.4 μM or 2 μM) and 84G3-4 (2 μM).

Earlier, we have found that an anti-αvβ3 cpAb, including that prepared with compounds 1 or 2 and Ab 38C2, inhibited the growth of both primary and metastatic tumors of several human cancers in mouse models.19 Based on our results, we argue that an anti-αvβ3 compound or a cpAb can inhibit primary tumor growth and metastasis to distant organs presumably by invoking several pathways, including inhibiting angiogenesis, and prepventing initial adhesion of the cancer cells to their distant organ vasculature and tisssues. Therefore, it seems to be less likely that an anti-integrin compound, Ab or our cpAbs may cause actual regression of an established primary tumor, or have major effects on established metastases. Moreover, if tumor cells overexpress more than one integrin-type, it may be essential to inhibit all integrins that functionally contribute to primary tumor growth and/or metastasis of such cells, as the integrins compensate each other’s function. Indeed, in a separate Pilot Study, we found that the anti-αvβ3,αvβ6 integrin cpAb 84G3-4 had little effect on an established mouse metastasis model of human SJSA1-Lung osteosarcoma, which also overexpress multiple integrins, including α5β1 and α2β1, besides αvβ3, in vivo (not shown)

In Summary, novel cell-targeting cpAbs were prepared based on the aldolase Ab-programming strategy using a series of Abs, including 38C2, 84G3, 85H6 and 90G8, and a dual inhibitor of integrins αvβ3 and αvβ6. The resulting cpAbs bound efficiently and specifically to a variety of highly metastatic human cells expressing integrins αvβ3 and αvβ6. Importantly, the cpAbs specifically inhibited adhesion of target tumor cells from various metastatic human cancers to extracellular matrix proteins that are relevant during tumor growth and metastatic progression. In vitro, these cpAbs have little toxicity on cell growth and viability at low micromolar or nanomolar concentrations. We anticipate that the anti-αvβ3 and αvβ6 compounds and cpAbs can be best used for directing agents to specifically deliver therapeutic agents, and that they can be used in combination with cytotoxins or other therapeutic agents to tumors, the tumor vasculature and tumor microenvironments. A dual targeting strategy against integrins αvβ3 and αvβ6 by our specific cpAb is likely to have application in the diagnosis and therapy of a broader range of human cancers expressing either or both integrins. Moreover, an anti-αvβ3 and αvβ6 integrin cpAb can provide reagents to study combined effect of αvβ3 and αvβ6 in vitro, and αvβ3 and αvβ6-mediated pathologies in vivo, including tumor angiogenesis, fibrosis and epithelial cancers.31,44 Finally, this study highlights the versatility and specificity of our aldolase antibody programming approach to generate highly efficient tools for diagnostic and possibly therapeutic applications, and as an alternative to the classical antibody-integrin inhibitor conjugates.45–46

Supplementary Material

Table 1.

Aldolase Ab programming using the DK and pVK compounds, 1 and 2.

| Ab | pH 6.0, 1.5 h | pH 7.4, 1.5 h | pH 8.5, 1.5 h | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Catalytic activity (%) | Ab Prog. (%) | Catalytic activity (%) | Ab Prog. (%) | Catalytic activity | Ab Prog. (%) | ||||||||||

| Ab | Ab-1 | Ab-2 | Ab-1 | Ab-2 | Ab | Ab-1 | Ab-2 | Ab-1 | Ab-2 | Ab | Ab-1 | Ab-2 | Ab-1 | Ab-2 | |

| 24H6 | 0 | 1 | 0 | - | - | 2 | 0 | 0 | - | - | 2 | 0 | 1 | - | - |

| 38C2 | 2 5 |

0 | 0 | 10 0 |

- | 24 | 0 | 1 | 10 0 |

96 | 23 | 0 | 3 | 10 0 |

87 |

| 33F12 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 10 0 |

10 0 |

5 | 1 | 0 | - | - | 6 | 0 | 0 | 10 0 |

10 0 |

| 84G3 | 8 3 |

0 | 64 | 10 0 |

23 | 10 0 |

0 | 50 | 10 0 |

50 | 97 | 0 | 50 | 10 0 |

48 |

| 84G11 | 2 | 0 | 0 | - | - | 28 | 0 | 3 | 10 0 |

89 | 34 | 0 | 3 | 10 0 |

91 |

| 85A2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | - | - | 21 | 0 | 3 | 10 0 |

86 | 23 | 0 | 2 | 10 0 |

91 |

| 85C7 | 0 | 0 | 1 | - | - | 2 | 0 | 0 | - | - | 4 | 0 | 1 | - | - |

| 85H6 | 4 | 1 | 4 | - | - | 25 | 1 | 3 | 96 | 88 | 12 | 0 | 1 | 10 0 |

92 |

| 90G8 | 2 | 0 | 4 | - | - | 19 | 0 | 1 | 10 0 |

95 | 19 | 0 | 2 | 10 0 |

91 |

| 92F9 | 1 | 0 | 0 | - | - | 8 | 0 | 0 | 10 0 |

10 0 |

9 | 0 | 0 | 10 0 |

10 0 |

| 93F3 | 2 2 |

0 | 18 | 10 0 |

18 | 25 | 0 | 7 | 10 0 |

72 | 23 | 0 | 5 | 10 0 |

78 |

Key: Three sets of reactions were performed by incubating the Abs with compounds 1 and 2 for 0.5 and 1.5 hrs, respectively, at pH 6.0, 7.4 and 8.5, and the methodol assay was used to determine the extent of the Ab programming. Catalytic rates of the untreated Abs and the cpAbs are compared to the highest activity that was observed with the untreated Ab 84G3. To determine the catalytic rates using the methodol assay, methodol (200 μM) was added to the Abs and cpAbs (1 μM) and formation of 6-methoxy-2-naphthaldehyde was measured using a fluorometer (Also see: Supporting Information)

Table 2.

Aldolase Ab programming using the DK and pVK compounds, 4 and 5.

| Ab | pH 7.4, 0.5 or 1.5 h | pH 7.4, 36 h | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Catalytic activity (%) | Ab Prog. (%) | Catalytic activity (%) | Ab Prog. (%) | |||||

| Ab | Ab-4 | Ab-5 | Ab-4 | Ab-5 | Ab | Ab-5 | Ab-5 | |

| 38C2 | 22 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 100 | |||

| 84G3 | 90 | 0 | 46 | 100 | 49 | 100 | 8 | 92 |

| 85H6 | 22 | 1 | 3 | 95 | 86 | 21 | 0 | 100 |

| 90G8 | 18 | 0 | 1 | 100 | 94 | 17 | 0 | 100 |

Key: Reactions were performed by incubating the Abs with compounds 4 for 0.5 and compound 5 for 1.5 or 36 hrs at pH 7.4, and progress of the chemical programming was determined using the methodol assay, as described earlier (Table 1). Catalytic rates of the untreated Abs and the cpAbs are compared to the highest activity that was observed with the untreated Ab 84G3.

Acknowledgments

We express our thanks to Professor Carlos F. Barbas of this Institute for the helpful discussions and the aldolase antibodies, Dr. Ronny Drapkin and the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA for OVCA-429 and OVCA-433 cell lines, and to Dr. Stephen Nishimura of UCSF Medical Center, San Francisco, California, for the SW480 cell lines and the anti-αvβ8 integrin 14E5 mouse Ab. This work was supported by NIH grants CA120289 to SCS and CA112287 to BFH, California Breast Cancer Research Program grants 12NB0176 and 13NB0180 to BFH, and Department of Defense grants W81XWH-07-1-0421 and W81XWH-09-1-0690 to SCS and W81XWH-08-1-0468 to BFH.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Additional Figure depicting the extent of the chemical antibody programming using the methodol assay. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org

References

- 1.Caswell PT, Vadrevu S, Norman JC. Integrins: masters and slaves of endocytic transport. Nature Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:843–853. doi: 10.1038/nrm2799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shattil SJ, Kim C, Ginsberg MH. The final steps of integrin activation: the end game. Nature Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11:288–300. doi: 10.1038/nrm2871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Desgrosellier JS, Cheresh DA. Integrins in cancer: biological implications and therapeutic opportunities. Nature Rev Cancer. 2010;10:9–22. doi: 10.1038/nrc2748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cox D, Brennan M, Moran N. Integrins as therapeutic targets: lessons and opportunities. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2010;9:804–820. doi: 10.1038/nrd3266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van der Flier A, Badu-Nkansah K, Whittaker CA, Crowley D, Bronson RT, Lacy-Hulbert A, Hynes RO. Endothelial α5 and αv integrins cooperate in remodeling of the vasculature during development. Development. 2010;137:2439–2449. doi: 10.1242/dev.049551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Erdreich-Epstein A, Shimada H, Groshen S, Liu M, Metelitsa LS, Kim KS, Stins MF, Seeger RC, Durden DL. Integrins alpha(v)beta3 and alpha(v)beta5 are expressed by endothelium of high-risk neuroblastoma and their inhibition is associated with increased endogenous ceramide. Cancer Res. 2000;60:712–721. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koopman Van Aarsen LA, Leone DR, Ho S, Dolinski BM, McCoon PE, LePage DJ, Kelly R, Heaney G, Rayhorn P, Reid C, Simon KJ, Horan GS, Tao N, Gardner HA, Skelly MM, Gown AM, Thomas GJ, Weinreb PH, Fawell SE, Violette SM. Antibody-mediated blockade of integrin αvβ6 inhibits tumor progression in vivo by a transforming growth factor-B–regulated mechanism. Cancer Res. 2008;68:561–570. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Breuss JM, Gallo J, DeLisser HM, et al. Expression of the β6 subunit in development, neoplasia and tissue repair suggests a role in epithelial remodeling. J Cell Sci. 1995;108:2241–51. doi: 10.1242/jcs.108.6.2241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jones J, Watt FM, Speight PM. Changes in the expression of alpha v integrins in oral squamous cell carcinomas. J Oral Pathol Med. 1997;26:63–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1997.tb00023.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hakkinen L, Hildebrand HC, Berndt A, Kosmehl H, Larjava H. Immunolocalization of tenascin-C, α9 integrin subunit, and αvβ6 integrin during wound healing in human oral mucosa. J Histochem Cytochem. 2000;48:985–98. doi: 10.1177/002215540004800712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Regezi JA, Ramos DM, Pytela R, Dekker NP, Jordan RCK. Tenascin and β6 integrin are overexpressed in floor of mouth in situ carcinomas and invasive squamous cell carcinomas. Oral Oncol. 2002;38:332–6. doi: 10.1016/s1368-8375(01)00062-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ahmed N, Pansino F, Baker M, Rice G, Quinn M. Association between αvβ6 integrin expression, elevated p42/44 kDa MAPK, and plasminogen-dependent matrix degradation on ovarian cancer. J Cellular Biochem. 2002;84:675–686. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bates RC, Bellovin DI, Brown C, et al. Transcriptional activation of integrin β6 during the epithelialmesenchymal transition defines a novel prognostic indicator of aggressive colon carcinoma. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:339–47. doi: 10.1172/JCI23183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hazelbag S, Kenter G, Gorter A, et al. Overexpression of the avh6 integrin in cervical squamous cell carcinoma is a prognostic factor for decreased survival. J Pathol. 2007;212:316–24. doi: 10.1002/path.2168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lafrenie RM, Buckner CA, Bewick MA. Cell adhesion and cancer: is there a potential for therapeutic intervention? Exp Opin Therap Targ. 2007;11:727–731. doi: 10.1517/14728222.11.6.727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rader C, Sinha SC, Popkov M, Lerner RA, Barbas CF., III A chemically programmed monoclonal antibody for cancer therapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:5396–5400. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0931308100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li L-S, Rader C, Matsushita M, Das S, Barbas CF, III, Lerner RA, Sinha SC. Chemical-adaptor immunotherapy: design, synthesis and evaluation of novel integrin-targeting devices. J Med Chem. 2004;47:5630–5640. doi: 10.1021/jm049666k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rader C, Turner JM, Heine A, Shabat D, Sinha SC, Wilson IA, Lerner RA, Barbas CF., III A humanized aldolase antibody for selective chemotherapy and adaptor immunotherapy. J Mol Biol. 2003;332:889–899. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00992-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guo F, Das S, Mueller BM, Barbas CF, III, Lerner RA, Sinha SC. Breaking the one antibody-one target axiom. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:11009–11014. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603822103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goswami RK, Huang Z-Z, Forsyth JS, Felding-Habermann B, Sinha SC. Multiple catalytic aldolase antibodies suitable for chemical programming. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2009;19:3821–3824. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2009.04.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gavrilyuk JI, Wuellner U, Salahuddin S, Goswami RK, Sinha SC, Barbas CF., III An efficient chemical approach to bispecific antibodies and antibodies of high valency. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2009;19:3716–3720. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2009.05.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wagner J, Lerner RA, Barbas CF., III Efficient aldolase catalytic antibodies that use the enamine mechanism of natural enzymes. Science. 1995;270:1797–1800. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5243.1797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhong G, Lerner RA, Barbas CF., III Broadening the aldolase catalytic antibody repertoire by combining reactive immunization and transition state theory: new enantio- and diastereoselectivities. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 1999;38:3738–3741. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1521-3773(19991216)38:24<3738::aid-anie3738>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Popkov M, Rader C, Gonzalez B, Sinha SC, Barbas CF., III Small molecule drug activity in melanoma models may be dramatically enhanced with an antibody effector. Int J Cancer. 2006;119:1194–1207. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Doppalapudi VR, Tryder N, Li L, Aja T, Griffith D, Liao F-F, Roxas G, Ramprasad MP, Bradshaw C, Barbas CF. Chemically programmed antibodies: endothelin receptor targeting CovX-bodies. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2007;17:501–506. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Doppalapudia VR, Huanga J, Liua D, Jina P, Liua B, Lia L, Desharnaisa J, Hagena C, Levina NJ, Shieldsa MJ, Parisha M, Murphya RE, Del Rosarioa J, Oatesa BD, Laia JY, Matina MJ, Ainekulua Z, Bhata A, Bradshawa CW, Woodnutta G, Lerner RA, Lappe RW. Chemical generation of bispecific antibodies. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:22611–22616. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016478108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Felding-Habermann B, Mueller BM, Romerdahl CA, Cheresh DA. Involvement of integrin αv gene expression in human melanoma tumorigenicity. J Clin Invest. 1992;89:2018–2022. doi: 10.1172/JCI115811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rolli M, Fransvea E, Pilch J, Saven A, Felding-Habermann B. Activated integrin alphavbeta3 cooperates with metalloproteinase MMP-9 in regulating migration of metastatic breast cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:9482–9487. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1633689100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wayner EA, Orlando RA, Cheresh DA. Integrins alpha v beta 3 and alpha v beta 5 contribute to cell attachment to vitronectin but differentially distribute on the cell surface. J Cell Biol. 1991;113:919–929. doi: 10.1083/jcb.113.4.919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alkhalaf M, Jaffal S. Potent antiproliferative effects of resveratrol on human osteosarcoma SJSA1 cells: novel cellular mechanism involving the ERKs/p53 cascade. Free Rad Biol Med. 2006;41:318–325. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lidor YJ, Shpall EJ, Peters WP, Bast RC., Jr Synergistic cytotoxicity of different alkylating agents for epithelial ovarian cancer. Int J Cancer. 1991;49:704–710. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910490513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weinreb PH, Simon KJ, Rayhorn P, Yang WJ, Leone DR, Dolinski BM, Pearse BR, Yokota Y, Kawakatsu H, Atakilit A, Sheppard D, Violette SM. Function-blocking integrin αvβ6 monoclonal antibodies: distinct ligand-mimetic and nonligand-mimetic classes. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:17875–17887. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312103200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cambier S, Mu D-Z, O’Connell D, Boylen K, Travis W, Liu W-H, Broaddus VC, Nishimura SL. A Role for the Integrin αvβ8 in the Negative Regulation of Epithelial Cell Growth. Cancer Res. 2000;60:7084–7093. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rodionov VM, Postovskaja EA. Mechanism of formation of β-aryl-β-amino fatty acids by the condensation of aroatic aldehydes with malonic acid and its derivatives. J Am Chem Soc. 1929;51:841–847. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Johnson TB, Livak JE. Pyrimidines. CXLIX. The synthesis of aryl-substituted dihydrouracils and their conversion into uracil derivatives. J Am Chem Soc. 1936;58:299–303. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miyaura N, Suzuki A. Palladium-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions of organoboron compounds. Chem Rev. 1995;95:2457–2483. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sinha SC, Das S, Li L-S, Lerner RA, Barbas CF., III Preparation of integrin alpha(v)beta(3)-targeting Ab 38C2 constructs. Nature Prot. 2007;2:449–456. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhu X, Tanaka F, Lerner RA, Barbas CF, III, Wilson IA. Direct observation of an enamine intermediate in amine catalysis. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:18206–18207. doi: 10.1021/ja907271a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.List B, Barbas CF, III, Lerner RA. Aldol sensors for the rapid generation of tunable fluorescence by antibody catalysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:15351–15355. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.26.15351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Goodman SL, Hölzemann G, Sulyok GAG, Kessler H. Nanomolar small molecule inhibitors for αvβ6, αvβ5 and αvβ3 integrins. J Med Chem. 2002;45:1045–1051. doi: 10.1021/jm0102598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Simoni D, Rondanin R, Baruchello R, Rizzi M, Grisolia G, Eleopra M, Grimaudo S, Di Cristina A, Pipitone MR, Bongiorno MR, Arico M, Invidiata FP, Tolomeo M. Novel terphenyls and 3,5-diaryl isoxazole derivatives endowed with growth supporting and antiapoptopic properties. J Med Chem. 2008;51:4796–4803. doi: 10.1021/jm800388m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li E, Brown SL, Stupack DG, Puente XS, Cheresh DA, Nemerow GR. Integrin αvβ1 Is an Adenovirus Coreceptor. J Virol. 2001;75:5405–5409. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.11.5405-5409.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Humphries JD, Byron A, Humphries MJ. Integrin ligands at a glance. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:3901–3903. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Humphries MJ. Monoclonal antibodies as probes of integrin priming and activation. Biochem Soc Trans. 2004;32:407–411. doi: 10.1042/BST0320407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kok RJ, Schraa AJ, Bos EJ, Moorlag HE, Ásgeirsdóttir SA, Everts M, Meijer DKF, Molema G. Preparation and functional evaluation of RGD-modified proteins as αvβ3 integrin directed therapeutics. Bioconj Chem. 2002;13:128–135. doi: 10.1021/bc015561+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shin IS, Jang B-S, Danthi SN, Xie J, Yu S, Le N, Maeng J-S, Hwang IS, Li KCP, Carrasquillo JA, Paik CH. Use of antibody as carrier of oligomers of peptidomimetic αvβ3 antagonist to target tumor-induced neovasculature. Bioconj Chem. 2007;18:821–828. doi: 10.1021/bc0603485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.