Abstract

Background

While drug abuse is the 10th leading cause of mortality in the US, the public health care system has been slow to adopt a chronic disease approach with aggressively timed monitoring and interventions. Drug abuse remains isolated from adoption into the “chronic condition” model of care. This paper evaluates the efficacy of quarterly Recovery Management Checkups (RMC) on treatment reentry and long-term substance use in the context of chronic substance use disorders.

Methods

446 adult substance users were randomly assigned to RMC or a control group and assessed quarterly for 4 years (94% completion). The main outcome measures were: time from need to treatment reentry, frequency of treatment reentry, days of treatment, number of substance use related problems per month, and total days abstinent.

Results

Participants in the RMC condition were significantly more likely than participants in the control group to return to treatment sooner, to return at all, to return more times, and to receive more total days of treatment. They subsequently had significantly fewer quarters in need of treatment, fewer substance related problems per month, and more total days of abstinence. Effects were larger for those with earlier onset and higher crime/violence scores.

Conclusions

RMC is an effective method of monitoring and re-intervening with chronic substance users and is associated with improved long-term outcomes. A subgroup of people for whom RMC did not appear to be “enough,” signals a need to explore more intensive models to address chronicity.

Keywords: Addiction Treatment, Chronic, Substance Use Disorder

1. INTRODUCTION

Illicit drug use, the 10th leading cause of mortality in the U.S., has strong associations with other leading causes of mortality and contributes to a range of co-occurring health (e.g., cancer, heart disease, liver disease) and mental health (e.g., depression, anxiety) problems (Mokdad et al., 2004; Murray et al., 1997; Single et al., 2000; Chan et al., 2008; Single et al., 1999; Weisner et al., 2001). The combined impact is staggeringly clear: individuals with a drug dependence diagnosis use more health care services and die on average 22 years earlier than those without a diagnosis (61 vs. 83 years) (Neumark et al., 2000).

Early readmission to treatment after relapse and multiple episodes of treatment are associated with the increased likelihood of achieving sustained abstinence and the reduced likelihood of mortality (Scott et al., 2011). Historically, however, addiction treatment has been organized around discrete episodes of care in which a person seeks treatment, receives an assessment, is treated and released to the community within a few months – with an implicit assumption by clients, family and society that they will then maintain lifelong abstinence (Scott and Dennis, 2011). The hard facts tell a different story: 50–70% of persons leaving addiction treatment will likely resume substance use in the first year following treatment, most within the first 30–90 days (Scott et al., 2005a; Scott et al., 2005b; Simpson et al., 2002; Hser et al., 1998; Godley et al., 2007). In fact, over half the people entering treatment have been in treatment before' (Office of Applied Studies Treatment data set, 2009) and 3 to 4 admissions to treatment usually are necessary before 50% or more are able to sustain abstinence for a year or more (Dennis et al., 2005). Post-treatment relapse rates, multiple admissions and increased risk of mortality demonstrate the need for the addiction field to transition from an acute care model toward a longer-term disease management model.

Ongoing monitoring and early re-intervention have improved long-term outcomes for a range of chronic conditions, including asthma, cancer, diabetes, depression, and severe mental illness (Dennis and Scott, 2007; Dunbar-Jacob et al., 1995; Engel, 1977; Engel, 1980; Huber, 2005; Institute of Medicine, 2001; McLellan et al., 2000, Nicassio and Smith, 1995; Roter et al., 1998; Weisner et al., 2004). These approaches generally use regular monitoring and early re-intervention. The first Early Re-Intervention (ERI-1) experiment established the feasibility and efficacy of regular monitoring and early re-intervention via quarterly Recovery Management Checkups (RMC) with individuals with substance use disorders over a two-year period (Dennis et al., 2003; Scott et al., 2005). Results indicated that RMC participants were significantly more likely than those in the control group to return to treatment sooner and get more subsequent treatment. RMC participants also experienced significantly fewer total quarters in need of treatment, and were less likely to need treatment 2 years after intake. However, in spite of successful treatment linkage rates, only 39% of linked participants remained in treatment for 14 or more days. Given that individuals who stayed for 14 or more days were significantly more likely to end the quarter in recovery, improving engagement and retention rates is clearly a challenge for ongoing management of this condition. While results from ERI-1 were encouraging, it took a year for the intervention to significantly impact participant outcomes. A preliminary comparison of the 2-year outcomes from ERI-1 and the second Early Re-Intervention (ERI-2) experiment suggests that the revised protocol reported on here met--or improved--each of the above outcomes and that the effects grew every quarter (Scott and Dennis, 2009).

This paper reports the main findings of ERI-2 over 4 years and is one of the first studies to examine the relative effectiveness of this long-term approach to recovery management.

2. METHODS

2.1 Participant Eligibility

Participants were recruited from sequential intakes at the largest addiction treatment agency in Illinois between February and April of 2004. Inclusion criteria were: any substance use in the past 90 days and any past-year symptoms of substance use disorders. For logistical reasons, participants were excluded if they were: under 18, lived or planned to move outside of Chicago within 12 months, sentenced to a confined environment most of the next 12 months, mandated to treatment because of a driving under the influence offense, were not fluent in English or Spanish, or were cognitively unable to provide informed consent.

Participants were randomly assigned to the control group (quarterly assessment only) or to the experimental group (quarterly assessment plus RMC). Only a few participants failed to complete any follow-up interviews (.6% in ERI-2) Of those assigned to the experimental condition not everyone needed RMC, but most were in need of and received the RMC intervention in one or more quarters (87%; 15% for one quarter; 72% for multiple quarters). In each condition, over 99% of the clients provided one or more waves of interview data for inclusion in the analyses presented here and 87% completed all 8 quarterly follow-up interviews.

2.2 Recovery Management Checkup (RMC)

After interviewers completed the quarterly research interview and determined participants' eligibility and need for early re-intervention, they transferred RMC participants to a “Linkage Manager.” For eligible RMC participants, the Linkage Manager used motivational interviewing to: a) provide feedback to participants regarding their current substance use and related problems, b) discuss implications of managing addiction as a chronic condition, c) discuss treatment barriers and solutions, d) assess and discuss level of motivation for treatment, e) schedule treatment appointments, and f) accompany participants through the 1- to 4- hour treatment intake process as necessary. Later, an Engagement and Retention Protocol designed to improve retention rates was implemented. For those participants who refused the treatment option, the Linkage Manager and participant agreed upon an alternative action plan that included various behaviors the participant agreed to engage in to reduce or stop their substance use. At the next quarterly interview, Linkage Managers and participants once again reviewed participants' status and adherence to the various plans. For RMC participants reporting no use, the Linkage Manager met with them to briefly discuss ways in which their lives had changed as a result of being clean, what was working for them and what they would continue to do in the next 90 days to maintain their recovery. Detailed procedures and forms are available in the RMC manual (Scott and Dennis, 2003) Over 90% of the intervention sessions were delivered by two linkage managers, who were Caucasian Women over 30 with master's degrees (public health, social work), who had worked for 5 or more years in the field. They were trained and supervised by Dr. Scott. All sessions were also audio taped and a random sample of tapes were rated by an independent expert in motivational interviewing who provided input into the supervision and quality control process.

2.3 Objectives

The objective of this study was to evaluate the relative effectiveness of quarterly checkups on long-term outcomes of adult chronic substance users over 4 years. The hypotheses for this study are that relative to participants randomly assigned to the control group, RMC participants were expected to: H1) return to treatment sooner, H2) receive more treatment, H3) decrease substance use and H4) increase days of abstinence. For the first hypothesis, we were also interested in the extent to which any effects were moderated by baseline risk. For the last two hypotheses, we were interested in both the effect over 4 years and the cumulative effect on the last observation.

2.4 Outcome Measures

Table 1 provides the range, psychometrics and definition for each of the outcome measures. For the psychometrics, the mean, standard deviation, and Cronbach's alpha come from this sample but the test-retest data come from the earlier experiment (Dennis et al., 2003). Measures come from the Global Appraisal of Individual Needs (GAIN) (Dennis et al., 2003). On-site urine tests were used to minimize (less than 1.7%) the rate of underreporting. Tracking for follow-up was done using the model developed by Scott (2004). Staff were trained on the assessment and intervention by the authors. Interviewer and intervention sessions were audio-taped and randomly selected for review throughout the study to check for any slippage or contamination in the assessment and intervention delivery.

Table 1.

Definition of Key Outcome Measures

| TIME PERIOD/Variable (range, psychometrics): Definition |

|---|

| FROM RANDOMIZATION TO LAST OBSERVATION (month 48 for 93%) |

| Any Treatment Reentry (0–100%; test-retest kappa=.81). Whether the person re-entered treatment between the point of randomization (at 3 months) and last observation. |

| Times Reentered Treatment (0–9; M=1.4 and SD=1.8; test-retest Rho=.92). Number of times client reentered treatment between randomization and the last observation. |

| Total Days of Treatment (0–965; M = 48 and SD=80.4; test-retest Rho=.93). Based on the sum of days an individual received outpatient, intensive outpatient, residential, or inpatient treatment reported at each interview for a given period. |

| Quarters with >= 7 days OP or 14 days Residential (0–14; M=1.6 and SD=2.2; test-retest kappa=.57). The number of quarters a participant received at least 7 days of outpatient or 14 days of residential treatment, regardless of whether it was due to retention, step down or readmission. |

| Quarters Needing Treatment (0–15; M=8.2 and SD=5.2; test-retest kappa=.78). Defined as a participant living in the community (vs. incarcerated) who was not already in treatment and answered “yes” to any of the following questions: 1) During the past 90 days, have you used alcohol, marijuana, cocaine, or other drugs on 13 or more days? 2) During the past 90 days, have you gotten drunk or been high for most of 1 or more days? 3) During the past 90 days, has your alcohol or drug use caused you not to meet your responsibilities at work/school/home on 1 or more days? 4) During the past month, has your substance use caused you any problems? 5) During the past week, have you had withdrawal symptoms when you tried to stop, cut down, or control your use? 6) Do you feel that you need to return to treatment? Within each quarter these criteria for need are internally consistent (alpha=.85) and the average person in need endorsed 3.3 of 6 of the items (80% endorsed 2 or more). |

| Successive Quarters Needing Treatment (0–15; M = 2.20 and SD=2.32; test-retest Rho=.92). The number of quarters in which the individual started and ended the period “in need of treatment” (see definition above) where missing data were replaced with status at prior wave. |

| Substance Problem × Months (0–720; M =107.3 and SD=124.1; alpha=.93; test-retest Rho=.99). Count of 16 past-month items related to weekly use, hiding using, complaints about use, 4 symptoms of abuse, 7 symptoms of dependence, substance induced health or mental health asked for the month before each quarterly interview times 3 and summed over observations; using mean score for any missing observations. |

| Total Days of Abstinence (0–1350; M = 475 and SD=170.39; test-retest Rho=.99). Sum of days abstinent from alcohol or other drugs in months 4 to 48 (max=1350 days); using the mean days per quarter for any missing observations. |

| AT LAST OBSERVATION |

| Substance Frequency Scale (0–1; M = 0.11 and SD = 0.17; alpha=.82; test-retest Rho = .95). Average of the percent of days (out of the past 90) reported on 8 items: any AOD use, days of heavy AOD use, days of problems from AOD use, and days of alcohol, marijuana, crack/cocaine, and heroin/other opioid use, days staying high most of the day, and days use caused problems at home, school or work. Higher scores represent increasing frequency of substance use, breadth of use, and extent of functional impairment. |

| Substance Problem Past Month (0–16; M = 2.5 and SD=4.16; alpha=.93; test-retest Rho=.81). Count of 16 past-month items related to weekly use, hiding using, complaints about use, 4 symptoms of abuse, 7 symptoms of dependence, substance induced health or mental health problems. |

| Days of Abstinence (0–90; M = 68 and SD=31.11; test-retest Rho=.94). Days abstinent from alcohol or other drugs in the 90 days before the 48-month interview using the last interview for any missing observation. |

2.5 Sample Size

The original sample size target of 300 was designed to be sufficient to have 80% power in a two tailed test with p<.05 for 2 group effects of sizes of .36 or more assuming at least 90% follow-up (Dennis et al., 1997). Under a supplement from the National Institute of Drug Abuse (NIDA) the sample size was expanded to support an additional subgroup and secondary analyses.

2.6 Randomization

Randomization was done in Excel using a random number generator. Participant research IDs were blocked into sequential units of four to balance out the work load; within each block, half were assigned to receive RMC and half to the outcome monitoring only control condition. Randomization was done by the first author just prior to the 3-month interview and only revealed to field staff at the point of the initial intervention. Research assistants completed all assessments and only participants randomized to RMC and in need of treatment were transferred to the Linkage Manger. All interviews and intervention sessions were logged and audio-taped. A review of the logs and random sample of audiotapes revealed no contamination between conditions.

2.7 Statistics

All analyses were conducted with SPSS (PASW Base 17.0.2, 2008) using an intent to treat design (i.e., participants were analyzed per random assignment regardless of actual services received). Dichotomous outcomes were analyzed with chi-square, continuous outcomes with general linear model (GLM), and time to event using Lifetables. In each case, the only predictor was random assignment. The effect of multiple baseline risk factors and random assignment were examined univariately and multivariately using Cox Proportional Hazards. Clinical significance for each pair wise contrast was reported in terms of Cohen's (1998) two-group effect size d and interpreted as d=.2=small, d=.4=moderate and d=.8 or more=large. Where 3 to 15 waves of follow-up data were missing by wave or item, they were replaced with the mean value of other waves to avoid the bias associated with list wise deletion. Because only a small amount of data was missing, this and more complex models do not vary in their results and the simpler approach is reported here.

3. RESULTS

3.1 Participant Flow

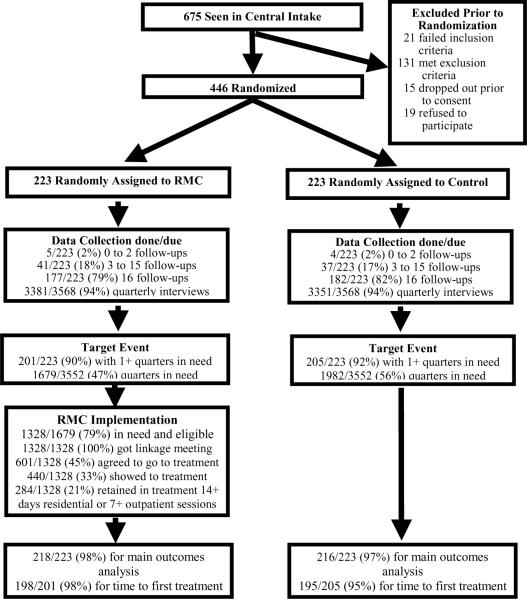

Figure 1 shows the participant flow through the trial. Of the 675 people presenting to central intake, 21 (3%) failed to meet all inclusion criteria and 131 (19%) were dropped for one or more exclusion criteria. Of the 480 passing all inclusion and exclusion criteria, 15 (3%) dropped out prior to completing the consent process and 19 (4%) refused to participate. The final sample of 446 was 149% of the original recruitment sample (300). These extra cases where collected under a supplemental award from NIDA to allow for additional follow-up and subgroup analyses. Of the 446 participants, 223 (50%) were randomly assigned to the Recovery Management Checkup (RMC) experimental group and 223 (50%) were randomly assigned to the control group.

Figure 1. Early Re-Intervention Experiment 2 (ERI-2) Participant Flow.

This figure shows the flow of participants, from the initial point of recruitment through randomization, data collection and intervention and the final number of people used in the analyses is presented here.

Of the 223 assigned to the RMC group, 5 (2%) completed 0 to 2 of the 16 quarterly follow-up interviews and were dropped from the analysis, 41 (18%) completed 3 to 15 follow-up interviews, and 177 (79%) completed all 16 follow-up interviews. Of the planned quarterly interviews, 3381 (94%) were completed. Of the 223 assigned to the control group, 4 (2%) completed 0 to 2 of the 16 quarterly follow-up interviews and were dropped from the analysis, 37 (17%) completed 3 to 15 follow-up interviews and 182 (82%) completed all 16 follow-up interviews. Of the planned quarterly interviews, 3351 (94%) were completed.

RMC is only delivered when a participant needs treatment. Of the 223 assigned to the RMC group with a follow-up interview, 201 (90%) were in need of treatment in 1 or more quarters and were in need of treatment in 1679 of 3552 (47%) of the quarters observed. Of the 223 assigned to the control group with a follow-up interview, 205 (92%) were in need of treatment in 1 or more quarters and were in need of treatment in 1982 of 3552 (56%) of the quarters observed.

RMC was delivered after interviews completed in months 3 to 45 if the person was in need of treatment and eligible (i.e., living in the Chicago metropolitan area, not currently in jail and not in treatment already); of the 1679 quarters in need, RMC participants were also eligible in 1328 quarters. Of the 1328 quarters in which someone was found in need and eligible, 1328 times (100%) the participant received a linkage meeting, 601 times (45%) they agreed to go to treatment, 440 times (33%) they showed to treatment, and 284 times (21%) they were retained in treatment at least for 14 days residential or for 7 outpatient sessions.

Of the 223 people in the RMC group, 218 (98%) had data for the main outcomes analysis and 198 (98% of 201) had data for the subgroup analysis of time from first need to treatment readmission. Of the 223 people in the control group, 216 (97%) had data for the main outcomes analysis and 195 (95% of 205) had data for the subgroup analysis of time from first need to treatment readmission.

3.2 Baseline Characteristics

Participants were on average 38 years of age, male (54%), African American (85%), never married (63%), unemployed (68%), had children under 21 (73%; 23% in their custody, 38% in custody of others, 8% with mixed custody) and 12% were recently pregnant. Over 62% had been homeless in their lifetime. Substance dependence (88%) was met primarily for cocaine (61%), opioids (25%), alcohol (24%), and cannabis (5%). Most (91%) reported using tobacco and 49% met criteria for tobacco dependence. The sample reported high rates of co-occurring psychiatric disorders (56%), illegal activity (54%), infectious diseases (32%), and other major health problems (25%). Participants also reported multiple risks related to HIV and other infectious diseases, including being sexually active (94%), having unprotected sex (60%) high levels of victimization (56%), multiple sex partners (37%), trading sex for money, drugs, or food (19%), needle use (4%), and needle sharing (1%). The group reported high rates of system involvement including reporting 5 or more admissions to a hospital or emergency department (51%), 5 or more arrests (33%), 5 or more addiction treatment admissions (31%) and 5 or more times in a mental hospital (6%). There were no significant differences by condition at baseline in any of the above characteristics.

3.3 Time Periods

Participants were recruited from sequential substance abuse treatment admissions on the west side of Chicago between February and April of 2004. Quarterly follow-up interviews were conducted between May of 2004 and June of 2008.

3.4 Main Outcomes

H1: Return to Treatment Sooner

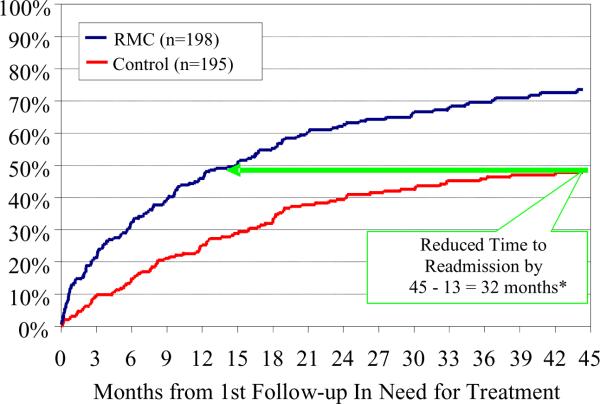

Figure 2 shows the months between the first quarter in need after randomization and the first readmission to treatment. Participants randomly assigned to RMC were significantly more likely than participants in the control group to return to treatment sooner (13 vs. 45 months, Cohen's effect size d=0.61).

Figure 2. Months from first follow-up in need of treatment to readmission.

The x- axis shows the time from the first quarter where the participants met criteria for needing to be readmitted to treatment and the first time they went back to treatment. The y-axis shows the cumulative percent having returned to treatment. The two lines show the survival curves for participants assigned to the Recovery Management Checkup (RMC) and Control Group. The differences between the two groups 1) increase every quarter 2) represent a reduction of 32 months from the final level in the control group and 3) are statistically significant (*Wilcoxon-Gehen(1)=28.60, p<.0001, Cohen's d=0.61).

H2: Receive More Treatment

The first 4 rows of Table 2 show the cumulative amount of treatment received after the point of randomization (end of month 3) between months 4 to 48. Participants randomly assigned to RMC were significantly more likely than those in the control group to have returned to treatment (70% vs. 51% admitted, d=0.50), to have returned to treatment more times (1.9 vs. 1.0 admissions, d=0.63), to receive more total days in treatment (112 vs. 79 days, d=0.23), and to stay in treatment for at least 7 days of outpatient or 14 days of residential treatment (2.04 vs. 1.22 times, d=0.37).

Table 2.

Outcomes by Condition and Time

| Time Frame/Measure (range) | RMC (n=218) | Control (n=216) | F or Chi-Sq | p | da |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Across Months 4 to 48 | |||||

| Any Treatment Reentry (0–100%) | 70% | 51% | 17.64 | p<.001 | 0.50 |

| Times Reentered Treatment (0–9) | 1.9 | 1.0 | 26.63 | p<.001 | 0.63 |

| Total Days of Treatment (0–965) | 112 | 79 | 5.52 | .019 | 0.23 |

| Quarters with >= 7 days OP or 14 days residential (0–14) | 2.04 | 1.22 | 15.99 | p<.001 | 0.37 |

| Quarters Needing Treatment (0–15) | 7.6 | 8.9 | 7.88 | .005 | −0.25 |

| Successive Quarters Needing Tx (0–15) | 5.9 | 7.5 | 11.17 | .001 | −0.30 |

| Substance Problem x Months (0–720) | 89 | 126 | 9.83 | .009 | −0.27 |

| Total Days of Abstinence (0–1350) | 1026 | 932 | 7.63 | .006 | 0.24 |

| Last quarter observed | |||||

| Substance Frequency Scale (0–1) | 0.10 | 0.13 | 5.86 | .016 | −0.19 |

| Substance Problem Past Month (0–16) | 1.4 | 2.3 | 6.97 | .009 | −0.22 |

| Days of abstinence (0–90) | 70 | 63 | 4.69 | .031 | 0.20 |

For continuous measures, Cohen's Effect size d calculated as RMC mean minus the control mean divided by the control group SD; for dichotomous measures, d was calculated as using the difference in the 2*arc sin transformation.21

P less than .05 and |d|≥.2 are highlighted in bold.

H3: Reduce Use and Problems

The subsequent rows of Table 2 show that participants in the RMC group reported significantly fewer quarters in “need” of treatment (7.6 vs. 8.9 quarters in need, d= −0.25), experienced shorter runs of successive quarters being in need (5.9 vs. 7.5 quarters in a row, d= −0.30), and fewer substance related problems per month (89 vs. 126 problem × months, d=−0.27). During the last quarter observed, RMC participants scored significantly lower than the control group participants on the Substance Frequency Scale (0.10 vs. 0.13 on a scale of 0 to 1, d= −0.19) and the Substance Problem Scale (1.4 vs. 2.3 on a scale of 0 to 16, d= −0.22).

H4: Increase Days Abstinent

Participants assigned to RMC reported significantly more total days abstinent from any AOD than the control group over the 4-year period (1026 vs. 932 of 1350 days, d=0.24) and at the last observation (70 vs. 63 of 90 days, d=0.20). Note that we conducted on-site urine analysis on all participants who claimed to be abstinent for the past 7 days and probed for clarity when inconsistent results arose. The false negative rate (i.e., claiming abstinence but positive on urine test) was 1.7% on average with no significant differences by condition.

3.5 Other Subject Factors Impacting the Time to Readmission

For the subset of the people with one or more quarters in need of additional treatment, we also wanted to examine whether RMC's effect on reducing the time to readmission held even after controlling for several other potential baseline factors using Cox proportional hazards model. Table 3 shows the bivariate and multivariate odds ratio of each baseline predictor, where values above 1.0 suggest less time to return to treatment and values below 1.0 suggest more time to return to treatment. In the bivariate analysis, returning to treatment sooner was associated with a) opioids as the primary substance use disorder; b) high scores on the substance problem scale, c) 3 or more prior treatment admissions, and d) random assignment to RMC. In contrast, longer times to return to treatment were associated with a) receiving their first treatment within 10 years of initial use and b) being the first treatment admission. In the multivariate model with all 18 variables considered at the same time, only randomization to RMC remained a significant predictor of time to return to treatment (OR=2.47, 95% CI 1.84 to 3.32, p<.05).

Table 3.

Cox Regression to predict quicker time from first quarter in need to treatment re-entry

| Odds Ratio (OR)\a |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bivariate | Multivariate | ||||||

| 95% CI |

95% CI |

||||||

| Predictor | Frequency | OR | Lower | Upper | OR | Lower | Upper |

| Female (vs. Male) | 176 | 1.06 | 0.82 | 1.37 | 1.00 | 0.75 | 1.32 |

| Age: 18–38 | 192 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| 39+ | 201 | 1.18 | 0.91 | 1.53 | 0.86 | 0.58 | 1.28 |

| Criminal Justice Sys. Involvement | 152 | 1.04 | 0.80 | 1.35 | 1.20 | 0.88 | 1.64 |

| Prime Severity Drug: Alcohol | 73 | 1.39 | 0.73 | 2.67 | 0.78 | 0.36 | 1.68 |

| Cocaine | 201 | 1.76 | 0.97 | 3.19 | 0.92 | 0.43 | 2.00 |

| Opiate | 89 | 2.12 | 1.14 | 3.95 | 1.14 | 0.51 | 2.53 |

| Other\b | 30 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Substance Frequency Scale | 393 | 1.10 | 0.97 | 1.25 | 0.97 | 0.83 | 1.14 |

| Substance Problem Scale | 393 | 1.19 | 1.04 | 1.36 | 1.13 | 0.92 | 1.38 |

| Internal Mental Distress Scale | 393 | 1.11 | 0.98 | 1.26 | 1.08 | 0.89 | 1.33 |

| Behavior Complexity Scale | 393 | 1.11 | 0.98 | 1.26 | 0.99 | 0.82 | 1.20 |

| Crime/Violence Scale | 393 | 1.09 | 0.96 | 1.23 | 1.09 | 0.93 | 1.27 |

| First used: under age 15 | 144 | 1.20 | 0.78 | 1.84 | 1.12 | 0.60 | 2.09 |

| 15 to 20 | 196 | 1.16 | 0.76 | 1.76 | 1.21 | 0.70 | 2.11 |

| 21+ | 52 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| First treatment: 36+ | 159 | 1.19 | 0.82 | 1.74 | 1.23 | 0.51 | 2.94 |

| 25–35 | 144 | 1.07 | 0.73 | 1.58 | 0.88 | 0.49 | 1.56 |

| under age 25 | 62 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Time to 1st Tx: less than 10 years | 105 | 0.55 | 0.39 | 0.78 | 1.11 | 0.51 | 2.83 |

| 10–19 years | 125 | 0.91 | 0.68 | 1.22 | 1.05 | 0.61 | 1.79 |

| 20+ years | 163 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| RMC after: 15 + years since 1st | 35 | 1.08 | 0.66 | 1.78 | 0.88 | 0.42 | 1.82 |

| 1–14 years since 1st | 177 | 1.61 | 1.22 | 2.11 | 1.26 | 0.85 | 1.85 |

| 1st treatment episode | 181 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Prior Treatment: 3+ prior episodes | 108 | 1.71 | 1.24 | 2.36 | 1.44 | 0.91 | 2.29 |

| 1 to 2 prior episodes | 137 | 1.32 | 0.97 | 1.82 | 1.20 | 0.81 | 1.79 |

| None | 148 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Initial Residential Tx (vs. OP) | 319 | 1.39 | 0.98 | 1.98 | 0.79 | 0.49 | 1.26 |

| Initial Length of Stay in Weeks | 379 | 1.01 | 1.00 | 1.02 | 1.00 | 0.98 | 1.01 |

| Satisfaction with Initial Treatment | 382 | 1.02 | 0.89 | 1.17 | 0.93 | 0.80 | 1.08 |

|

| |||||||

| RMC (vs. Control) | 198 | 2.05 | 1.57 | 2.67 | 2.47 | 1.84 | 3.32 |

Where above 1 is sooner and below 1 is later; Continuous Variables are transformed to z-scores (i.e., OR per standard deviation), length of stay in weeks.

Other drug consists of 24 with marijuana, 3 with amphetamines and 3 with other psychotropic drugs.

Bold indicates p<.05

3.6 Evidence of Subject by Treatment Interactions

Next we conducted subject by treatment interactions on each of the variables in Table 3 by assignment to RMC for the two variables: the total days of abstinence and the number of substance problem-months. For total days of abstinence, there was evidence of statistically significant subject by RMC interactions for 2 of 17 subject variables from Table 3, with the positive effects of RMC being more prominent among those with high crime and violence scores (mean of 1053 vs. 786 days of abstinence; F(1,96)=13.94, p<.001, d=0.71) and for those who first used under age 15 (mean of 1060 vs. 840 days of abstinence; F(1,947)=15.32, p<.001, d=0.58). For the number of substance problem-months, there was evidence of statistically significant subject by RMC interactions for 1 of 17 variables from Table 3, with the positive effects of RMC being more prominent among those with who started using under age 15 (mean of 77 vs. 161 problem-months; F(1,167)=18.76, p<.001, d= −0.63).

3.7 Adverse Events

As noted in the baseline characteristics, the participants started with a high rate of problems and institutionalization and continued to have these problems during follow-up, though at a lower rate. There were significant differences in 17 serious and adverse events tracked: RMC participants reported significantly fewer days of being victimized by others (7 vs.14 days, p<.05). RMC was also equal to or better than the control group in the other areas.

4. DISCUSSION

Perhaps one of the most poignant findings from this study was the significant need for long-term monitoring and re-intervention. At some point during the 4 years of this study, 90% of the participants were in need of treatment beyond what they received during the initial episode. Approximately 70% were in need of more treatment in 5 or more quarters over 4 years. The high follow-up rates further demonstrated that, despite the often chaotic and highly mobile lifestyles that often accompany chronic substance use, quarterly monitoring is clearly a feasible option and that individuals are willing to participate at this level. This addresses what has been a vexing, prevalent, and long-term problem health and behavioral health care industries have faced for decades

Results indicated that ongoing monitoring and early re-intervention via recovery management checkups was associated with reduced time to substance abuse treatment readmission, receipt of more treatment, reduced substance use and substance related problems, and increased abstinence. Results further indicated that RMC was particularly effective for individuals that reported earlier age of onset of substance use or greater involvement with crime or violence. While RMC helped many individuals and the cumulative effects increased over time, the effect of each subsequent RMC intervention declined and there was a subgroup of people for whom RMC may not be the optimal intervention.

The variation in response to this approach to managing addiction demonstrates the need for developing and testing other approaches for managing addiction. There is some observational evidence that more intensive models (e.g., more frequent contact, urine monitoring, and involvement in self help) have worked for the Physician Health Program (PHP) (McLellan, et al., 2008, DuPont et al., 2009; Shore, 1987; Domino et al., 2005). Conversely, there is also observational data suggesting that less burdensome and lower costs approaches (e.g., mobile phones, volunteers, self help group participation) can also be effective (Gustafson et al., 2002; Kelly and White, 2011; Pingree et al., 2010). It should be noted that by doing randomization and producing over 95% follow-up in quarterly waves over 4 years in this study we have methodologically opened the door to being better able to study these alternatives as well.

In spite of the study's strengths, there are limitations. The data are from a single predominately African American urban sample with high rates of co-occurring disorders. There is a need to replicate the model in other populations and geographic areas. In addition, though urine analysis was used to improve the validity, self-report was the main data source. Ideally, it would be useful to have more frequent urine monitoring and to learn more about the sequence of events within each quarter that led up to relapse. The RMC approach is also labor intensive and the existing financially overburdened treatment systems may limit its availability. While analyses here identified subgroups where the effects were bigger, this happened in 3 of 34 (9%) of the subject by treatment interactions and should ideally be replicated as well.

In conclusion, the main findings of ERI-2 over four years are an encouraging confirmation that we are indeed one step closer to effectively responding to addiction as a chronic illness. The treatment field, the larger medical community, and the overall health care system can benefit from what RMC offers: a pro-active approach to help substance abusers learn to identify their symptoms, resolve their ambivalence about their substance use, and support their choice to assume personal responsibility for the management of their long-term recovery process. Yet more work remains to be done on determining the optimal frequency and duration of interventions and if there is a subgroup for whom it works better or worse or for whom it has stopped working. More work is also still needed on the cost and cost effectiveness of RMC overall and for specific subgroups that have in ordinate costs to society. Finally, other interventions are also clearly needed to expand the tool box for managing addiction as a chronic condition.

Acknowledgement

We gratefully acknowledge Rachael Bledsaw, Nancy Dudley, Rod Funk and Joan Unsicker for assistance in preparing the manuscript, as well as the Chestnut research staff, Haymarket clinical staff and families who participated in the study.. Comments can be directed to Dr. Michael Dennis, Chestnut Health Systems, 448 Wylie Drive, Normal, IL 61761, 309-451-7801, mdennis@chestnut.org.

Role of Funding Source: Financial assistance for this study was provided by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA; grant number R37 DA11323). The opinions represented here are those of the authors and to not represent official positions of the government.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributors: Dr. Dennis led the design of the study, instrumentation and analysis. Dr. Scott led the design and implementation of the intervention and the field work. They both participated in all aspects of developing this paper.

Conflicts of Interests: No conflicts of interest declared.

References

- Chan YF, Dennis ML, Funk RR. Prevalence and comorbidity co-occurrence of major internalizing and externalizing disorders among adolescents and adults presenting to substance abuse treatment. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 2008;34:14–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.12.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Lawrence Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Dennis ML, Scott CK, Funk R. An experimental evaluation of recovery management checkups (RMC) for people with chronic substance use disorders. Eval. Program. Plann. 2003;26:339–352. doi: 10.1016/S0149-7189(03)00037-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis ML, Scott CK, Funk R, Foss MA. The duration and correlates of addiction and treatment careers. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 2005;28:S51–S62. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2004.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis ML, Scott CK. Managing addiction as a chronic condition. J. Addict. Sci. Clin. Prac. 2007;4:45–55. doi: 10.1151/ascp074145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis ML, Titus JC, White M, Unsicker J, Hodgkins D. Global Appraisal of Individual Needs (GAIN): Administration guide for the GAIN and related measures. V. 5 ed. Chestnut Health Systems; Bloomington, IL: 2003. [Accessed June 25, 2010]. http://www.chestnut.org/LI/gain/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- Dennis ML, Lennox RD, Foss M. Practical power analysis for substance abuse health services research. In: Bryant KJ, Windle M, West SG, editors. The Science of Prevention: Methodological Advances from Alcohol and Substance Abuse Research. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 1997. pp. 367–404. [Google Scholar]

- Domino KB, Hornbein TF, Polissar NL, Renner G, Johnson J, Alberti S, Hankes L. Risk factors for relapse in health care professionals with substance abuse disorders. JAMA. 2005;293:1453–1460. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.12.1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunbar-Jacob J, Burke LE, Puczynski S, Nicassio PM. Managing Chronic Illness: A Biopsychosocial Perspective. American Psychological Association Press; Washington D. C.: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- DuPont RL, McLellan AT, White WL, Merlo LJ, Gold MS. Setting the standard for recovery: physicians' health programs. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 2009;36:159–171. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2008.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel GL. The need for a new medical model: a challenge for biomedicine. Science. 1977;196:129–136. doi: 10.1126/science.847460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel GL. The clinical application of the bio-psychosocial model. Am. J. Psych. 1980;137:535–544. doi: 10.1176/ajp.137.5.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godley MD, Godley SH, Dennis ML, Funk RR, Passetti LL. The effect of assertive continuing care on continuing care linkage, adherence, and abstinence following residential treatment for adolescents with substance use disorders. Addiction. 2007;102:81–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01648.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustafson DH, Hawkins RP, Boberg EW, McTavish F, Owens B, Wise M, Berhe H, Pingree S. CHESS: 10 years of research and development in consumer health informatics for broad populations, including the underserved. Int. J. Med. Info. 2002;65:169–177. doi: 10.1016/s1386-5056(02)00048-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hser YI, Grella CE, Chou CP, Anglin MD. Relationships between drug treatment careers and outcomes: findings from the National Drug Abuse Treatment Outcome Study. Eval. Rev. 1998;22:496–519. [Google Scholar]

- Huber DL. Disease Management: A Guide for Case Managers. Elsevier; Amsterdam: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine . Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. National Academy Press; Washington, DC: 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JF, White WL. Recovery Management and the future of addiction treatment and recovery in the USA. In: Kelly JF, White WL, editors. Addiction Recovery Management: Theory, Research and Practice, Current Clinical Psychiatry. Springer Science+Business Media, LLC; New York, NY: 2011. pp. 303–316. [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, Lewis DC, O'Brien CP, Kleber HD. Drug dependence, a chronic medical illness: implications for treatment, insurance, and outcomes evaluation. JAMA. 2000;284:1689–1695. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.13.1689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, Skipper GS, Campbell R, DuPont RL. Five year outcomes in a cohort study of physicians treated for substance abuse disorders in the United States. BMJ. 2008;337:a2038. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a2038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mokdad AH, Marks JS, Stroup DF, Gerberding JL. Actual causes of death in the United States, 2000. JAMA. 2004;291:1238–1245. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.10.1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray CJL, Lopez AD. Global mortality, disability, and the contribution of risk factors: global burden of disease study. Lancet. 1997;349:1436–42. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)07495-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumark YD, Van Etten ML, Anthony JC. “Drug dependence” and death: survival analysis of the Baltimore ECA sample from 1981–1995. Subst. Use Misuse. 2000;35:313–327. doi: 10.3109/10826080009147699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicassio PM, Smith TW, editors. Managing Chronic Illness: A Biopsychosocial Perspective. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Office of Applied Studies . National Admissions to Substance Abuse Treatment Services. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; Rockville, MD: 2001. Treatment Episode Data Set (TEDS): 1994–1999. (DASIS Series). S-14 (DHHS Publication No. (SMA) 01-3550) Retrieved from http://www.DrugAbuseStatistics.samhsa.gov. [Google Scholar]

- Office of Applied Studies . ICPSR24461-v1. Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research [distributor]; Ann Arbor, MI: 2009. Treatment Episode Data Set -- Discharges (TEDS-D), 2006. doi:10.3886/ICPSR24461 [2009-06-22] [Google Scholar]

- PASW Base 17.0.2 command syntax reference. Version 17. Statistical Program for the Social Sciences (SPSS); Chicago, IL: 2008. computer program. [Google Scholar]

- Pingree S, Hawkins R, Baker T, DuBenske L, Roberts LJ, Gustafson DH. The value of theory for enhancing and understanding e-health interventions. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2010;38:103–109. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.09.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roter DL, Hall JA, Merisca R, Nordstrom B, Cretin D, Svarstad B. Effectiveness of interventions to improve patient compliance: a meta-analysis. Med. Care. 1998;36:1138–1161. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199808000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott CK. A replicable model for achieving over 90% follow-up rates in longitudinal studies of substance abusers. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2004;74:21–36. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2003.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott CK, Dennis ML. Results from two randomized clinical trials evaluating the impact of quarterly recovery management checkups with adult chronic substance users. Addiction. 2009;104:959–971. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02525.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott CK, Dennis ML. Recovery Management Check-ups: An Early Reintervention Model. Lighthouse Institute; Chicago, IL: 2003. [Accessed June 29, 2010]. http://www.chestnut.org/LI/downloads/Scott_&_Dennis_2003_RMC_Manual-2_25_03.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Scott CK, Dennis ML. Recovery management checkups with adult chronic substance users. In: Kelly JF, White WL, editors. Addiction Recovery Management: Theory, Research, and Practice. Springer; New York, NY: 2011. pp. 87–102. [Google Scholar]

- Scott CK, Dennis ML, Foss MA. Utilizing recovery management checkups to shorten the cycle of relapse, treatment reentry, and recovery. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005a;78:325–338. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott CK, Dennis ML, Laudet A, Funk RR, Simeone RS. Surviving drug addiction: the effect of treatment and abstinence on mortality. Am. J. Public Health. 2011;101:737–744. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2010.197038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott CK, Foss MA, Dennis ML. Utilizing recovery management checkups to shorten the cycle of relapse, treatment reentry, and recovery. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005b;78:325–338. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott CK, Foss MA, Dennis ML. Pathways in the relapse, treatment, and recovery cycle over three years. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 2005c;28:S63–S72. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2004.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson DD, Joe GW, Broome KM. A national 5-year follow-up of treatment outcomes for cocaine dependence. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2002;59:538–544. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.6.538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Single E, Rehm J, Robson L, Truong MV. The relative risks and etiologic fractions of difference causes of death and disease attributable to alcohol, tobacco and illicit drug use in Canada. CMAJ. 2000;162:1669–1675. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Single E, Robson L, Rehm J, Xie X, Xi X. Morbidity and mortality attributable to alcohol, tobacco, and illicit drug use in Canada. Am. J. Public Health. 1999;89:385–390. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.3.385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shore JH. The Oregon experience with impaired physicians on probation. JAMA. 1987;257:2931–2934. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisner C, McLellan T, Barthwell A, Blitz C, Catalano R, Chalk M, Chinnia L, Collins RL, Compton W, Dennis ML, Frank R, Hewitt W, Inciardi JA, Lightfoot M, Montoya I, Sterk CE, Wood J, Pintello D, Volkow M, Michaud SE. Report of the Blue Ribbon Task Force on Health Services Research at the National Institute on Drug Abuse. National Institute on Drug Abuse; Rockville, MD: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Weisner C, Mertens J, Parthasarathy S, Moore C, Lu Y. Integrating primary medical care with addiction treatment: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2001;286:1715–1723. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.14.1715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]