Abstract

Objectives

Problems such as hospital malnutrition (∼40% prevalence in the UK) may be managed better by improving the nutrition education of ‘tomorrow's doctors’. The Need for Nutrition Education Programme aimed to measure the effectiveness and acceptability of an educational intervention on nutrition for medical students in the clinical phase of their training.

Design

An educational needs analysis was followed by a consultative process to gain consensus on a suitable educational intervention. This was followed by two identical 2-day educational interventions with before and after analyses of Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices (KAP). The 2-day training incorporated six key learning outcomes.

Setting

Two constituent colleges of Cambridge University used to deliver the above educational interventions.

Participants

An intervention group of 100 clinical medical students from 15 medical schools across England were recruited to attend one of two identical intensive weekend workshops.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

The primary outcome measure consisted of change in KAP scores following intervention using a clinical nutrition questionnaire. Secondary outcome measures included change in KAP scores 3 months after the intervention as well as a student-led semiqualitative evaluation of the educational intervention.

Results

Statistically significant changes in KAP scores were seen immediately after the intervention, and this was sustained for 3 months. Mean differences and 95% CIs after intervention were Knowledge 0.86 (0.43 to 1.28); Attitude 1.68 (1.47 to 1.89); Practice 1.76 (1.11 to 2.40); KAP 4.28 (3.49 to 5.06). Ninety-seven per cent of the participants rated the overall intervention and its delivery as ‘very good to excellent’, reporting that they would recommend this educational intervention to colleagues.

Conclusion

Need for Nutrition Education Programme has highlighted the need for curricular innovation in the area of clinical health nutrition in medical schools. This project also demonstrates the effectiveness and acceptability of such a curriculum intervention for ‘tomorrow's doctors’. Doctors, dietitians and nutritionists worked well in an effective interdisciplinary partnership when teaching medical students, providing a good model for further work in a healthcare setting.

Article summary

Article focus

Hospital malnutrition has been a challenge for decades in the UK due to its cost and impact on patient care.

The focus was to examine whether a novel 2-day course could make a significant improvement in the understanding of clinical nutrition, among senior medical students.

Key messages

This study summarised the need for improved training in clinical nutrition among medical students in England, a need noted in other countries too.

Statistically significant changes in KAP scores were seen immediately after the intervention among the 98 students, and this was sustained for 3 months.

Ninety-seven per cent of the participants rated the overall intervention and its delivery as ‘very good to excellent’, reporting that they would recommend this educational intervention to colleagues.

Strengths and limitations of this study

The learning outcomes seemed appropriate and the teaching intervention appeared effective.

A multidisciplinary teaching team helped emphasise the roles of various team members, in dealing with nutrition-related problems in a healthcare setting.

Comparing change to a parallel student control group would have been preferable to monitoring within-group change.

Introduction

The prevalence of malnutrition in the UK hospitals has been reported to be as high as 40% (higher than the European Union average) for almost two decades, with ∼£13 billion of associated healthcare costs, which are potentially avoidable through early secondary prevention.1–3 Early recognition and appropriate management in healthcare settings is essential, as is follow-up in the community.4

Doctors can play a crucial role in the recognition, prevention and treatment of malnutrition. However, previous surveys of health professionals regarding the assessment and management of undernutrition concluded that their knowledge was poor and provided a strong argument for further educational initiatives.5 6 The same lack of knowledge of clinical nutrition and its application has also been noted among medical students by researchers in Canada and the USA.7–12 Over recent decades, nutrition training in the UK medical curricula has been displaced by a number of other disciplines. Integrated educational initiatives have now been recommended, including the diagnosis and management of both undernutrition and overnutrition to reflect the ‘double burden’ of nutritional problems.13–15 However, there have been no further studies to assess current levels of nutrition knowledge or skills in the British medical workforce.

In 2009, the national guidance on medical education published by the General Medical Council highlighted nutrition as a doctor's responsibility,16 and the recent white paper on NHS reforms by the UK government assigned the highest priority to improving healthcare outcome.17 Doctors need to understand the role played by diet and nutrition in health promotion and disease prevention/management and need to take active roles in partnership with other health professions, as well as patients and their families.18 Thus, Need for Nutrition Education Programme (NNEdPro) was developed to highlight the need for nutrition education in medical schools and to evaluate the effectiveness of a nutrition education intervention in a cohort of ‘tomorrow's doctors’ using Knowledge, Attitude and Practice (KAP) scores related to clinical nutrition.19

Methods

Development of the intervention

Harden's20 10 question system for planning a course was used to formulate, monitor and evaluate the course methodology (box 1).

Box 1. Evaluation of teaching and learning methods: Harden's 10 objectives.

To assess needs relative to the product of the institution.

To define aims and objectives of the course.

To determine course content.

To decide on course organisation.

To outline educational strategies.

To select teaching methods.

To delineate course assessment.

To communicate curriculum details.

To agree on the educational environment.

To devise a process management mechanism.

Use of this system was followed by an educational needs analysis, consisting of an online survey of a national sample of medical students about clinical nutrition. We analysed the results with a panel of experts to gain consensus on curriculum content, learning outcomes, the educational intervention and questionnaire used to evaluate KAP. This panel became the teaching team. A comprehensive overview of current national nutritional policy and recommendations, as well as their clinical application, was also provided to students.

Learning outcomes were based on the new recommendations for nutrition-related learning outcomes proposed for the UK undergraduate medical curricula by the Inter-Collegiate Group on Nutrition, as shown in box 2.21

Box 2. Learning outcomes recommended by IGCN.

Recognition that nutrition forms an important part of a doctor's responsibilities;

understanding core principles of ‘Food, Fluid and Nutritional Care’ in hospital related to ‘Recognition, Prevention and Management of Malnutrition’;

awareness of nationally agreed standards for nutritional care;

ability to conduct ‘MUST’ (‘Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool’) scoring, recording this in medical notes and care plans, as well as mentioning this in discharge documents22 23;

ability to use the results of the ‘MUST’ screening to contribute to the formulation of care plans24;

promotion of protected patient mealtimes.

The intervention

Each 2-day workshop consisted of a combination of lectures, demonstrations, simulations and interactive practical sessions (small group work) and incorporated concepts of problem-based learning (mini-PBL). This provided students with a comprehensive overview of clinical and public health aspects of nutrition, as well as an understanding of how these can be applied and implemented in practice. The role of the doctor and broader multidisciplinary healthcare team in delivering nutritional care was explored, and students were given the opportunity to apply knowledge of the nutritional needs of specific populations in practical care planning sessions. The programme included both under- and over-nutrition as well as systems-based teaching/learning. A core component of this programme consisted of the prevention, identification and management of under-nutrition. Students were given the opportunity to participate in practical sessions using validated nutritional screening methods, including the use of the ‘Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool' (MUST), and to review the role of different management strategies. A spiral learning approach revisited topics on day 2 to build upon consolidated basic concepts. The approach was novel as it was a short intervention but included quantitative and qualitative outcomes.

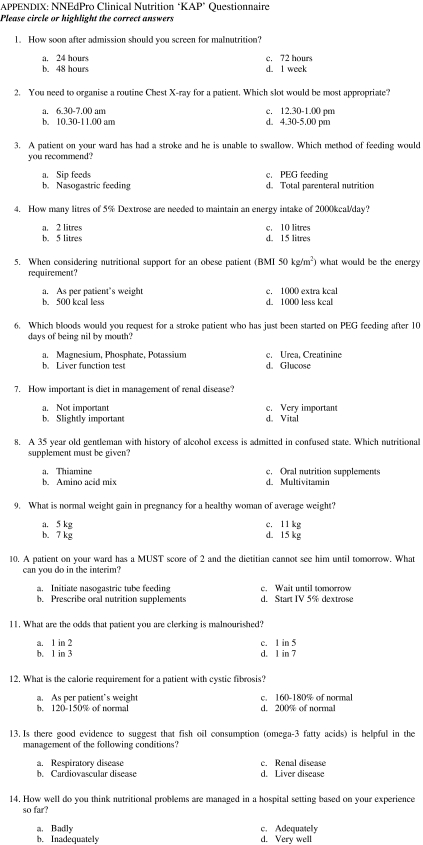

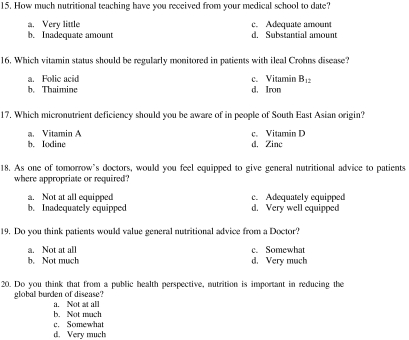

Evaluation of the intervention

Before and after the intervention, KAP scores were assessed using a questionnaire-based instrument, which was construct-validated against key clinical learning outcomes. Questionnaire items were randomised differently at baseline and postintervention, to minimise recall bias. The study design also incorporated longitudinal follow-up using identical outcome measures after 3 months (appendix 1).

Approvals and recruitment

At the time of first conceiving this study, the study team were based at the University of Dundee and sought approval from the Tayside Research Ethic Committee. It was deemed by the committee chairman that as this constituted the evaluation of an educational innovation and did not involve patients or healthcare data, it could be suitably exempt from the need for ethics approval. This exemption was confirmed in writing. Participants on the educational course provided written consent to the anonymised results of the course evaluation being used for educational evaluation/research purposes.

The sampling frame consisted of all 23 medical schools in England. The medical school secretaries were contacted by the NNEdPro recruitment co-ordinator using a dedicated email. This communication included an overview of the educational intervention and was cascaded by the secretaries to all medical students in the penultimate year/phase of their clinical training. A total of 461 medical students from 15 medical schools responded directly to the NNEdPro group. Non-probability quota sampling was employed to recruit an intervention group of 100 students.

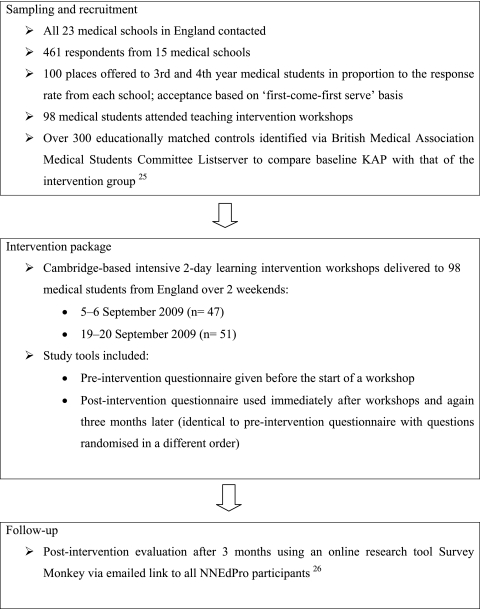

Participants were self-selected based on degree of motivation, and several medical schools were included leading to variation in the amount of nutrition teaching received. These had the potential to introduce selection bias. However, a pragmatic view was taken whereby this recruitment approach was both practical and feasible. A proportionate distribution of participants was ensured by allocating proportional quotas based on school response rate. Details on recruitment procedures are in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Study overview. KAP, Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices; NNEdPro, Need for Nutrition Education Programme.

Data analysis

Considering the normal distribution of the data, the paired t test was used both to evaluate the change in parameters of interest from baseline scores (postintervention scores minus preintervention scores) and to check test–retest reliability using pre- and postintervention information (I) scores. In theory, the ‘I’ scores should be the same for each participant in the pre/postquestionnaire. Since several measurements taken on the same individuals tend to be correlated, repeated measures of analysis of variance were conducted to compare mean scores over the whole follow-up period, including 3-month follow-up. To see if the sample was representative, we compared baseline scores of the intervention group with an educationally matched control group (medical students who had not received the nutrition education intervention) using a median test that performs a non-parametric K-sample test on the equality of medians.

A likelihood-based (random intercept) model was used to examine predictors of the Practice score. The dependent variable ‘Practice’ was defined as a multi-item proxy scale designed to assess potential practices. The observation level covariates (ie, ones that varied at repeated observations) included Attitude and Knowledge scores. Data analysis was performed using STATA software, V.9.27 All statistical tests were two-sided, and statistical significance level α was set at 0.05 for all analyses. Workshop evaluation was analysed using SPSS V.14.28

Results

All 98 participants completed the questionnaire before and after the intervention. Baseline mean scores and mean difference scores between participants at weekend 1 and weekend 2 sessions were similar, and further analysis was performed using combined scores over both weekends. There was a significant postintervention change in parameters of interest from baseline (table 1).

Table 1.

Change from baseline in knowledge, attitude, practice and KAP after intervention

| Mean differences and 95% CI* comparing postintervention scores to baseline (N=98) | |

| Knowledge | 0.86 (0.43 to 1.28) |

| Attitude | 1.68 (1.47 to 1.89) |

| Practice | 1.76 (1.11 to 2.40) |

| KAP | 4.28 (3.49 to 5.06) |

p≤0.0001.

KAP, Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices.

There were 80 responses at the 3-month follow-up, of which 68 were evaluable (seven people did not provide any identification information, there was one double entry and four incomplete questionnaires). Analysis of variance demonstrated a statistically significant difference in scores over the follow-up time (table 2). Mean scores were higher at the postintervention assessment and then decreased at the 3-month assessment but remained higher compared to baseline (table 2).

Table 2.

Mean KAP scores at baseline, postintervention and 3-month follow-up

| Baseline* (N=98) | Postintervention* (N=98) | After 3 months* (N=68) | p Value† | |

| Knowledge | 4.10±2.08 | 4.96±1.75 | 4.15±2.22 | 0.0004 |

| Attitude | 9.15±0.92 | 10.84±0.71 | 9.91±0.91 | 0.0000 |

| Practice | 15.2±2.57 | 16.97±2.02 | 16.10±2.38 | 0.0000 |

| KAP | 28.5±3.50 | 32.77±2.79 | 30.16±3.46 | 0.0000 |

Values are presented as mean±SD.

p Value is from a repeated measures analysis of variance.

KAP, Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices.

The mean ‘I’ scores showed statistically significant differences between preintervention, postintervention and 3-month follow-up scores. Median tests comparing baseline scores of the intervention group with the control group demonstrated differences that were not statistically significant, implying that the sample population was representative (table 3).

Table 3.

Median KAP scores (IQR) for the intervention group at baseline and for educationally matched controls

| Information | Knowledge | Attitude | Practice | KAP | |

| Control | 4 (3–5) | 4 (2–4) | 9 (8–10) | 14 (11–16) | 26 (22–30) |

| Intervention | 3.5 (3–4) | 4 (2–6) | 9 (9–10) | 16 (14–17) | 29 (26–31) |

KAP, Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices.

Regression analysis was based on a total of 264 observations from 98 participants, with each contributing two or three data points, depending on the frequency of their participation in follow-up assessment. The overall mean Practice score (across subjects) was estimated (in the null model) as 16.09 (95% CI 15.79 to 16.40). According to the results, 5% of the variance in Practice score can be attributed to differences between subjects. In the model, Attitude was a significant predictor of Practice score, whereas Knowledge was not. The estimated increase in mean Practice score for a one-unit increase in Attitude score was equal to 0.55 units (95% CI 0.29 to 0.80, p<0.001). The effect of Knowledge was not significant, with the coefficient equal to 0.03 (95% CI −0.11 to 0.18).

The educational workshops were very well received by the 98 participants from across 15 medical schools. Ninety-seven per cent of participants rated the overall intervention and its delivery as ‘very good to excellent’, reporting that they would recommend this educational intervention to colleagues. Ninety-four per cent rated the level of teaching as appropriate, and 99% demonstrated recall of one or more of these following six key take-home messages:

Discussion

Implications of study

NNEdPro assessed the impact of an intensive package of nutrition education designed to lay the foundations of nutritional knowledge and attitudes relevant to clinical practice, in particular raising awareness of the recognition, prevention and management of malnutrition in hospital and highlighting the principles of ‘Nutrition, a doctor's responsibility’.

The project established normative, expressed and comparative need for undergraduate nutrition education in medical schools and also defined six key areas for curricular change/innovation.

There were both statistically and educationally significant postintervention increments in Knowledge, Attitudes and Practice scores, with an overall increase being sustained after 3 months. There were no significant baseline differences between the two intervention groups suggesting that the educational intervention can be delivered in a consistent and reliable manner. Regression modelling demonstrated that Attitude scores were a positive predictor of Practice scores. This finding is of potential importance as the course placed particular emphasis on changing attitudes towards nutritional care.

NNEdPro workshops incorporated innovative teaching methods including clinical simulation, mini-PBL and spiral learning. Spiral learning is usually employed in a vertical teaching strand over a protracted period of time. Similarly, PBL usually requires a time interval such as a week during which students facilitate peer-led learning, adjourning to reach consensus on learning outcomes. This educational intervention used these concepts as far as possible, within the confines of a very short ‘one-off’ course. Based on both quantitative and qualitative findings, these methods appear to have contributed positively to the outcomes of the intervention. As part of the educational research component of NNEdPro, quasi-experimental methods were combined with traditional qualitative approaches in medical education. Finally, in terms of teaching, NNEdPro demonstrated that doctors, dietitians and scientists can work in an effective interdisciplinary partnership when teaching medical students and health professionals.

NNEdPro findings are relevant to curriculum planners, policymakers and all stakeholders seeking to improve the management of nutritional problems. From a broader medical education angle, this project also has the potential to act as a model for curricular innovation and change. There is a need to translate the educational impact of the NNEdPro intervention into clinical settings. Committed participants from the NNEdPro cohort could receive a leadership training package and take on the role of regional champions. These ‘satisfied adopters’ would then disseminate key nutrition-related messages to health professionals in their local NHS using ‘change management’ principles.31 The impact of this could be evaluated against sustainable change in clinical practices and clinical outcomes relating to hospital malnutrition.

Increasing the productivity and quality of the nutritional care workforce, including doctors, nurses and other healthcare professionals, is an essential component of efforts to mitigate the burden of hospital malnutrition in the UK. NNEdPro demonstrates that bringing about such changes is possible in a study population of ‘tomorrow's doctors’ and sets the stage for further applied and action research in healthcare settings.

Constraints

First, the relatively small sample of students (98) was chosen from a self-selected group of medical students. Such a bias might mean that they were more interested and motivated than average medical students in England, with respect to nutrition, though our control group noted no significant difference in knowledge. The final participants were chosen using non-probability quota sampling, creating the possibility that this group was not fully representative of the 461 individuals who applied. We must also consider the extent to which the change in KAP noted was a result of the teaching intervention syllabus or whether it might be attributed to any other confounding factor. For instance, the 15 different medical schools from which the participants were recruited had varying degrees of nutrition education in their respective curricula. In addition, a 2-day intensive teaching package at a national centre led by a motivated team may have produced results that could be hard to replicate with more conventional teaching. Finally, comparing change to a parallel student control group may have been preferable to monitoring within-group change.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Susan Jebb, UK Medical Research Council Human Nutrition Research (for internal peer review). Celia Laur, NNEdPro Intern (for editorial assistance).

Appendix 1

|

|

Footnotes

To cite: Ray S, Udumyan R, Rajput-Ray M, et al. Evaluation of a novel nutrition education intervention for medical students from across England. BMJ Open 2012;2:e000417. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000417

Contributors: SR conceptualised the research, sought the funding and refined the design proposal for the research. SR, MR-R, PD, RW and JG were involved in the planning, adjustment and implementation of the design. SR, PD and JG handled liaison with the British Dietetic Association who hosted the administration of the research. K-ML and BT oversaw participant recruitment. SR, MR-R, BT, K-ML, PS, RB, SS, RW, SG and JG were involved in the organisation or teaching of the two weekend courses. SR, BT and RU managed the evaluation, statistical analysis and interpretation. SR, RU, MR-R, K-ML, PD, PS, SS, SG, RW, MJvdE, IF and JG drafted or critiqued or rewrote part or all the manuscript. SR is the guarantor. SJ is acknowledged as she critiqued the final draft. SS checked the final document for accuracy.

Funding: This work was funded through an unrestricted educational grant from Abbott Nutrition. The study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of the data were handled independent of Abbott Nutrition.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: This study was exempted from the need for ethics approval at a discussion with the Tayside Ethics Committee, where the project was conceived.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Data may be shared as long as anonymity and confidentiality are preserved.

References

- 1.Edington J, Boorman J, Durrant ER, et al. Prevalence of malnutrition on admission to four hospitals in England. Clin Nutr 2000;19:191–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McWhirter JP, Pennington CR. Incidence and recognition of malnutrition in hospital. BMJ 1994;308:945–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Russell C, Elia M. Nutrition Screening Survey in the UK in 2008. British Association for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (BAPEN), UK, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 4.O'Flynn J, Peake H, Hickson M, et al. The prevalence of malnutrition in hospitals can be reduced: results from three consecutive cross-sectional studies. Clin Nutr 2005;24:1078–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kafatos A. Is clinical nutrition teaching needed in medical schools? Ann Nutr Metab 2009;54:129–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nightingale JM, Reeves J. Knowledge about the assessment and management of undernutrition: a pilot questionnaire in a UK teaching hospital. Clin Nutr 1999;18:23–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adams KM, Kohlmeier M, Powell M, et al. Invited Review: nutrition in medicine: nutrition education for medical students and residents. Nutr Clin Pract 2010;25:471–80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Adams KM, Kohlmeier M, Zeisel SH. Nutrition education in U.S. medical schools: latest update of a national survey. Acad Med 2010;85:1537–42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Collier R. Canadian medical students want more nutrition instruction. CMAJ 2009;181:133–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Daghigh F, Vettori DJ, Harris J. Nutrition in medical education: history, current status, and resources. Top Clin Nutr 2011;26:147–57 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frantz DJ, Munroe C, McClave SA, et al. Current Perception of nutrition education in U.S. Medical schools. Curr Gastroenterol Rep 2011;13:4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gramlich LM, Olstad DL, Nasser R, et al. Medical students' perceptions of nutrition education in Canadian universities. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab 2010;35:336–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Council of Europe Alliance UK 10 Key Characteristics for Good Nutritional Care. Council of Europe Alliance, UK, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 14.DeChicco R, Neal T, Guardino JM. Developing an education program for nutrition support teams. Nutr Clin Pract 2010;25:481–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Friedman G, Kushner R, Alger-Mayer S, et al. Proposal for medical school nutrition education: topics and recommendations. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2010;34(6 Suppl):40S–6S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.General Medical Council Tomorrow's Doctors; Outcomes and Standards for Undergraduate Medical Education. London: General Medical Council, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Department of Health Liberating the NHS', July 2010 Version. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Awad S, Herrod PJJ, Forbes E, et al. Knowledge and attitudes of surgical trainees towards nutritional support: food for thought. Clin Nutr 2010;29:243–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.NNEdPro Website of Need For Nutrition Education Programme. 2008. http://www.nnedpro.org.uk [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harden RM. Ten questions to ask when planning a course or curriculum. Med Educ 1986;20:356–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Inter-Collegiate Group on Human Nutrition Proposed Learning Objectives for the Undergraduate Medicine Nutrition Curriculum. London: Report on medical education curriculum on behalf of the Academy of Medical Royal Colleges, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Elia M, Russell CA. Combating Malnutrition; recommendations for action. In: Malnutrition Advisory Group, ed. London, 2009:5 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Malnutrition Advisory Group Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool. In: British Association for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (BAPEN), UK, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stratton RJ, King CL, Stroud MA. Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool predicts mortality and length of hospital stay in acutely ill elderly. Br J Nutr 2006;95:5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Medical Schools Council Medical Schools Council website. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 26.SurveyMonkey.com [program]. Palo Alto, California, USA: LLC, 2010. http://SurveyMonkey.com [Google Scholar]

- 27.STATA Version 9(program). 9 version. College Station, Texas: StataCorp LP, 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 28.SPSS Version 14(program). 14 version. Chicago, Illinois, USA: O SPSS Incorporated, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ross LJ, Mudge AM, Young AM, et al. Everyone's problem but nobody's job: Staff perceptions and explanations for poor nutritional intake in older medical patients. Nutr Diet 2011;68:41–6 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Heuer AJ, Geisler SL, Kamienski M, et al. Introducing medical students to the interdisciplinary health care team: piloting a case-based approach. J Allied Health 2010;39:76–80 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kotter JP. A Sense of Urgency. Boston, MA, USA: Harvard Business Press, 2008 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.