Abstract

Aim: Individuals differ in their inherited tendency to develop cancer. This has been suggested to be due to genetic variations between individuals. Single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) are the most common form of genetic variations found in the human population. The aim of this study was to investigate the association between 10 SNPs in genes involved in cell cycle control and DNA repair (p21 C31A, p53 G72C, ATM G1853A, XRCC1 G399A, XRCC3 C241T, Ku80 A2790G, DNA Ligase IV C9T, DNA-PKcs A3434G, TGF-beta T10C, MDM2 promoter T309G) and the risk to develop head and neck cancer. Materials and Methods: A cohort of 407 individuals (156 cancer patients and 251 controls) was included. DNA was extracted from peripheral blood. SNPs were genotyped by direct sequencing. Results: Data showed significant allelic associations for p21 C31A (p=0.04; odds ratio [OR]=1.44; confidence interval [CI]: 1.02–2.03), Ku80 A2790G (p=0.04; OR=1.5; CI: 1.01–2.23), and MDM2 T309G (p=0.0003; OR=0.58; CI: 0.43–0.78) and head and neck cancer occurrence. Both cancer cases and controls were in Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium. Conclusion: SNPs can be associated with head and neck cancer in the Saudi population. The p21 C31A, Ku80 A2790G, and MDM2 T309G SNPs could be used as genetic biomarkers to screen individuals at high cancer risk.

Introduction

Head and Neck cancer is the sixth most common, forming about 6% of all human malignancies (Parkin et al., 2005). Its incidence is increasing worldwide and the World Health Organization expects this trend to continue in the next several decades (Bettendorf et al., 2004). In Saudi Arabia, head and neck cancers represent 11% of all malignancies diagnosed annually (Authority NCR, 2006).

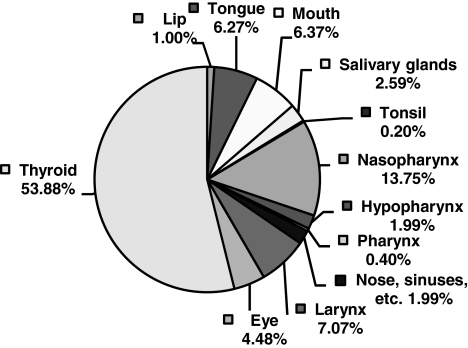

Cancer can develop in any of the tissues or organs in the head and neck. There are more than 30 different sites that cancer can occur in the head and neck area, which include oral cavity (lip, tongue, salivary glands, gum, and mouth floor), pharynx (nasopharynx, hypopharynx, and pharynx), and the larynx (Fig. 1) (Authority NCR, 2006). Head and neck cancers are strongly associated with alcohol consumption and exposure to tobacco smoke (Hashibe et al., 2007). Recently, associations between head and neck cancer risk and exposures to environmental and occupational factors have been suggested (Siemiatycki et al., 2004). In addition, human papillomavirus infection has been correlated with some groups of squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (HNSCC), particularly in the oropharynx (Chung and Gillison, 2009). Further, genetic variations in genes implicated in cell cycle regulation, DNA repair, apoptosis, and other cellular processes play important roles in the etiology of HNSCC (Ho et al., 2007).

FIG. 1.

Distribution of different head and neck cancers encountered in Saudi Arabia.

In 2001, sequencing of the human genome was finalized and it showed that genetic variations between individuals are small and amount to <1% of genetic sequences. These DNA sequence variations can take many forms: substitution of single nucleotides, insertion or deletion of single or multiple nucleotides, changes in the number of repetitive sequences, and larger changes in chromosome structure. Most variations involve single-nucleotide change and they are named single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). Depending on SNP frequency and the ability to cause disease, these variations are referred to as polymorphisms (with a frequency of >1% in the normal population) or mutations (<1%) (Brookes, 1999). Not all mutations result in disease and some polymorphisms are functionally important and have been implicated in disease pathogenesis.

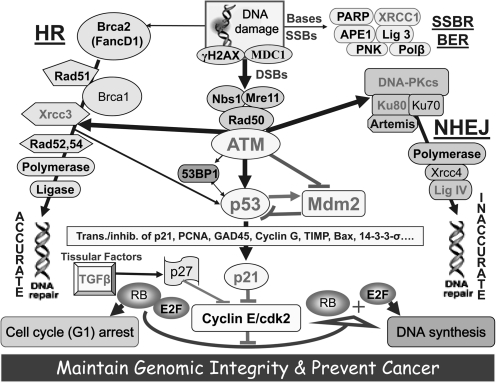

In the last decade, cancer researchers have investigated the link between SNPs and various endpoints such as drug resistance in chemotherapy, radiosensitivity in radiation therapy, and cancer susceptibility (Alsbeih et al., 2010). A number of studies have suggested that SNPs might contribute along with other factors to the development of various human malignancies (Zhou et al., 2007; Chiu et al., 2008). In particular, head and neck cancer predisposition was associated with several SNPs in various genes that may also have ethnic variations (Facher et al., 1997; Zhou et al., 2007). SNPs in genes involved in pathways related to cell-cycle control, DNA repair, and apoptosis are likely to affect cancer susceptibility. There are many proteins involved in these pathways (Fig. 2). Genetic variations in the encoding genes are frequent. Some of the genetic variations observed were linked to cancer predisposition. For example, the two major proteins along this pathway are p53 and its negative regulator MDM2. MDM2 is an ubiquitin ligase that plays a critical role in regulating the levels and activity of the p53 protein, which is a central tumor suppressor. Overexpression of the MDM2 oncoprotein promotes cell survival and cell cycle progression by inhibiting the p53 protein. Functional polymorphisms in both MDM2 and TP53 genes have been identified. An SNP in the intronic promoter of the human MDM2 gene (SNP309 T/G) occurs at frequencies dependent on demographic history. In western countries, approximately 40% of the population are heterozygous T/G and 12% are homozygous G/G (Bond et al., 2004). This SNP309 has differential effects on MDM2 and p53 proteins' activity and associates with altered risk for the development of several cancers. In vitro studies showed that the variant SNP309 G allele creates a high affinity binding site for Sp1 transcription factor, increases the expression of MDM2 mRNA and protein, and thereby suppresses the p53 pathway. Further, it has been suggested to decrease the response of tumor cells to certain forms of treatment such as radiation therapy and DNA-damaging drugs. The SNP TP53 codon 72 G/C (Arg/Pro) is more common in the general population. Molecular studies showed that the variant 72C allele can alter the transcription of p53 target genes and modifies the apoptotic potential of cells. This SNP was suggested to associate with the onset and risk of different cancer types. However, there is still a lack of such studies in the Saudi population. Therefore, the aim of this study was to investigate the association between 10 SNPs in genes (p21 C31A, p53 G72C, ATM G1853A, XRCC1 G399A, XRCC3 C241T, Ku80 A2790G, DNA Ligase IV C9T, DNA-PKcs A3434G, TGF-beta T10C, and MDM2 promoter T309G) involved in these pathways (Fig. 2) and head and neck cancers in Saudi Arabia.

FIG. 2.

Schematic representation of main pathways involved in response to DNA damage, repair, and cell cycle control. See text for genes in which single-nucleotide polymorphisms were selected in this study. Lines represent interactions. Arrows indicate activation and blunt ends indicate inhibition. Thickness represents the strength of the actions.

Materials and Methods

Clinical data

Blood samples were obtained from 156 Saudi head and neck cancer patients, mostly with nasopharyngeal carcinoma (122 men and 34 women; median age: 50; quartiles: 17; 77 years), and 251 healthy Saudi individuals (191 men and 60 women; median age: 47; quartiles: 23; 89 years). The patients were diagnosed and treated by the Radiation Oncology Department at the King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Centre. The institutional basic and ethics research committees have approved the study, and all volunteers and patients have signed an informed consent.

Selection of polymorphisms, DNA extraction, amplification, and sequencing

The selected SNPs along with the PCR primers are listed in Table 1. DNA was extracted from 5 mL peripheral whole blood, using the Puregene DNA Purification Kit (Gentra System). Relevant segments of DNA were amplified by thermal cycling (95°C for 15 min, 39 rounds of 95°C for 1 min, 56°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 1 min and final extension at 72°C for 7 min) using HotStarTaq DNA polymerase (Qiagen) in standard reaction conditions. The amplified fragments were directly sequenced using the DYEnamic ET Dye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Kit (Amersham Biosciences) and were run on the MegaBase 1000 sequencer (Applied Biosystems). Sequencing results were aligned to the corresponding reference sequence and the SNPs were genotyped using SeqManII sequence analysis software (DNASTAR, Inc.).

Table 1.

Ten Selected Single-Nucleotide Polymorphisms, Primers for Polymerase Chain Reaction Amplification, and DNA Sequencing

| |

|

|

|

PCR primers |

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene | Codon | SNP | Amino acid change | Forward | Reverse | NCBI dbSNP Id/reference |

| p21 | 31 | C/A | Ser/Arg | CGCCATGTCAGAACCGGCT | TTCCATCGCTCACGGGCC | rs1801270 |

| p53 (TP53) | 72 | G/C | Arg/Pro | TGGTCCTCTGACTGCTCTTTT | AACTGACCGTGCAAGTCACA | rs1042522 |

| ATM | 1853 | G/A | Asp/Asn | ATATGTCAACGGGGCATGAA | CATTAATATTGCCAGTGCAAG | rs1801516 |

| XRCC1 | 399 | G/A | Arg/Gln | GCCCCTCAGATCACACCTAA | GATAAGCAGGCTTCACAGAGC | rs25487 |

| XRCC3 (- strand) | 241 | C/T | Thr/Met | GGTTAGGCACAGGCTGCTAC | CTTGCTGACCAGCATAGACAA | rs861539 |

| Ku80 | – | A/G | – | CAAGGGATAATTTAGACCCCATA | GGGCCAAAAGGTCTTTTCTT | rs1051685 |

| DNA Ligase IV | 9 | A/G | Thr/lle | TCAAATTAGGGTTGGAGCAAA | TTCCATAGGCCATTCTCTCTC | rs1805388 |

| DNA-PKcs | 3434 | A/G | Ile/Thr | CCTTCCATTAGAGTGCCAT | ATGCACTGCACACACTAACG | rs7830743 |

| TGFβ1 | 10 | T/C | Leu/Pro | AGCCTCCCCTCCACCACT | TGGGTTTCCACCATTAGCAC | rs1982073 |

| MDM2 | – | T/G | – | GGATTTCGGACGGCTCTC | CTAACCAGGGTCTCTTGTTCC | rs2279744 |

NCBI, National Center for Biotechnology Information; ID, identification; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; SNP, single-nucleotide polymorphsim.

Data analysis

The association between cancer occurrence and SNPs' genotype and allelic frequencies were measured by the odds ratio (OR) with its confidence interval (CI). The degree of significance was calculated using the chi-squares method. A p-value of 0.05 or less was considered statistically significant. Further, Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) and deviation from HWE for genotype distribution were tested for each SNP with statistically significant association with head and neck cancer to study the disturbing influences of genotype frequency in the population by comparing the observed to the expected genotypes' frequencies.

Results

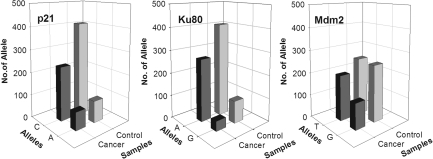

The genotype and allelic distributions of the assessed polymorphisms in the selected genes are listed in Table 2. The three genotypes, homozygous wild-type, heterozygous, and homozygous variants, were observed for p21 C31A, p53 G72C, XRCC1 G399A, XRCC3 C241T, Ku80 A2790G, TGFB1 T10C, and MDM2 promoter T309G in this cohort of Saudi individuals. Interestingly, there were two homozygous variants for ATM G1853A in the cancer patients against none in the control group. Also, the homozygous variants for DNA LIG IV C9T and DNA-PKcs T343C were infrequent. The frequencies in the cancer patients (cases) were compared with those in the volunteers without cancer (controls). Although the distribution of most SNPs studied were comparable between cases and controls, the p21 C31A, Ku80 A2790G, and MDM2 T309G showed differences. The heterozygous and homozygous variants of p21 C31A and Ku80 A2790G were more frequent in the cancer patients when compared with controls, suggesting that the variant confers higher risk to develop cancer. Also, the heterozygous and homozygous variants of MDM2 T309G were less frequent in the cases when compared with controls, suggesting that the variant has a protective effect. The genotype analysis comparing heterozygous to wild-type homozygous showed significant association for Ku80 A2790G (p=0.01) and MDM2 T309G (p=0.003) and a borderline significant association for p21 C31A (p=0.06; Table 2). Allelic frequencies have confirmed these results (Fig. 3) and showed significant associations between head and neck cancer and the allelic distribution of p21 C31A (p=0.04), Ku80 A2790G (p=0.04), and MDM2 T309G (p=0.0003).

Table 2.

Genotype and Allele Frequencies of 10 Assessed Single-Nucleotide Polymorphisms in a Cohort of 407 Saudi Individuals (156 With Head and Neck Cancer and 251 Controls Without Cancer)

| |

Total samples: 407 |

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene, genotype, and allele | Cancer(n=156) (%) | Control(n=251) (%) | Odds ratio (95% confidence interval) | Significance level p | Overall frequencies (%) | NCBI frequencies (%)a |

| p21 (CDKN1A) codon 31 C>A Ser/Arg | ||||||

| C/C | 87 (56) | 166 (66) | 62 | 55 | ||

| C/A | 61 (39) | 77 (31) | 1.51 (0.99–2.31) | 0.06 | 33 | 32 |

| A/A | 8 (5) | 8 (3) | 1.91 (0.69–5.25) | 0.28 | 5 | 13 |

| C | 235 (75) | 409 (81) | 79 | 71 | ||

| A | 77 (25) | 93 (19) | 1.44 (1.02–2.03) | 0.041 | 21 | 29 |

| p53 (TP53) codon 72 G>C Arg/Pro | ||||||

| G/G | 48 (31) | 71 (28) | 29 | 36 | ||

| G/C | 70 (45) | 110 (44) | 0.94 (0.59–1.51) | 0.81 | 44 | 41 |

| C/C | 38 (24) | 70 (28) | 0.80 (0.47–1.38) | 0.49 | 27 | 23 |

| G | 166 (53) | 252 (50) | 51 | 56 | ||

| C | 146 (47) | 250 (50) | 0.89 (0.67–1.18) | 0.43 | 49 | 44 |

| ATM codon 1853 G>A Asp/Asn | ||||||

| G/G | 131 (84) | 218 (87) | 85.5 | 88.7 | ||

| G/A | 23 (15) | 33 (13) | 1.15 (0.65–2.04) | 0.66 | 14 | 11 |

| A/A | 2 (1) | 0 (0) | N/A | 0.14 | 0.5 | 0.3 |

| G | 285 (91) | 469 (93) | 93 | 94 | ||

| A | 27 (9) | 33 (7) | 1.34 (0.79–2.27) | 0.33 | 7 | 6 |

| XRCC1 codon 399 G>A Arg/Gln | ||||||

| G/G | 96 (62) | 135 (54) | 57 | 54 | ||

| G/A | 50 (32) | 99 (39) | 0.70 (0.46–1.08 | 0.13 | 36 | 37 |

| A/A | 10 (6) | 17 (7) | 0.82 (0.36–1.86) | 0.68 | 7 | 9 |

| G | 244 (78) | 369 (74) | 75 | 70 | ||

| A | 70 (22) | 133 (26) | 0.79 (0.57–1.11) | 0.18 | 25 | 30 |

| XRCC3 codon 241 C>T Thr/Met | ||||||

| C/C | 51 (33) | 101 (40) | 37 | 44 | ||

| C/T | 86 (55) | 106 (42) | 1.60 (1.03–2.50) | 0.03 | 47 | 22 |

| T/T | 19 (12) | 44 (18) | 0.85 (0.45–1.61) | 0.64 | 16 | 34 |

| C | 188 (60) | 308 (61) | 61 | 56 | ||

| T | 124 (40) | 194 (39) | 1.05 (0.78–1.40) | 0.77 | 39 | 44 |

| Ku80 untranslated mRNA2790 A/G | ||||||

| A/A | 119 (76) | 164 (65) | 70 | 70 | ||

| A/G | 32 (21) | 79 (32) | 1.79 (1.11–2.88 | 0.01 | 27 | 26 |

| G/G | 5 (3) | 8 (3) | 1.16 (0.37–3.64) | 1 | 3 | 4 |

| A | 270 (87) | 407 (81) | 83 | 85 | ||

| G | 42 (13) | 95 (19) | 1.5 (1.01–2.23) | 0.04 | 17 | 15 |

| DNA Ligase IV codon 9 C/T Thr/lle | ||||||

| C/C | 132 (85) | 216 (86) | 85 | 71 | ||

| C/T | 24 (15) | 31 (12) | 1.27 (0.71–2.25) | 0.46 | 14 | 26 |

| T/T | 0 (0) | 4 (2) | N/A | 0.3 | 1 | 3 |

| C | 288 (92) | 463 (92) | 92 | 85 | ||

| T | 24 (8) | 39 (8) | 0.99 (0.58–1.68) | 1 | 8 | 15 |

| DNA-PKcs codon 3434 A/G Ile/Thr | ||||||

| A/A | 135 (87) | 212 (85.5) | 85.3 | 69 | ||

| A/G | 21 (13) | 38 (15) | 0.87 (0.49–1.54) | 0.67 | 14.5 | 27 |

| G/G | 0 (0) | 1 (0.5) | N/A | 1 | 0.2 | 4 |

| A | 291 (93) | 462 (92) | 92.5 | 82 | ||

| G | 21 (7) | 40 (8) | 0.83 (0.48–1.44) | 0.58 | 7.5 | 18 |

| TGFβ1 codon 10 T>C Leu/Pro | ||||||

| T/T | 51 (33) | 83 (33) | 33 | 57 | ||

| T/C | 67 (43) | 120 (48) | 0.91 (0.57–1.44) | 0.72 | 46 | 31 |

| C/C | 38 (24) | 48 (19) | 1.29 (0.74–2.23) | 0.4 | 21 | 12 |

| T | 169 (54) | 286 (57) | 56 | 79 | ||

| C | 143 (46) | 216 (43) | 1.12 (0.84–1.49) | 0.47 | 44 | 21 |

| MDM2 promoter309 T/G | ||||||

| T/T | 69 (44) | 67 (27) | 33 | N/A | ||

| T/G | 61 (39) | 120 (48) | 0.49 (0.31–0.79) | 0.003 | 45 | N/A |

| G/G | 26 (17) | 64 (25) | 0.39 (0.22–0.69) | 0.001 | 22 | N/A |

| T | 199 (64) | 254 (51) | 56 | N/A | ||

| G | 113 (36) | 248 (49) | 0.58 (0.43–0.78) | 0.0003 | 44 | N/A |

Manually calculated from NCBI Web site for each SNP.

N/A, not applicable.

FIG. 3.

Allele distributions of p21 C31A, Ku80 A2790G, and MDM2 T309G polymorphisms in head and neck cancer patients compared with healthy individuals.

For HWE tests, the 5% significance level for 1 degree of freedom is 3.84. Interestingly, none of the chi-squared values of the differences between expected and observed genotypes' counts of p21 C31A, Ku80 A2790G, and MDM2 T309G for both cancer and control were ≥3.84, suggesting that they are all in HWE (Table 3). Further, the frequencies observed in Saudi Arabia of all SNPs studied were comparable to those available at the National Center for Biotechnology Information Web site.

Table 3.

Test for Hardy–Weinberg Equilibrium and Deviation from Hardy–Weinberg Equilibrium for Single-Nucleotide Polymorphisms Significantly Associated with Head and Neck Cancer Occurrence

| |

Genotypes |

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-type | Heterozygote | Homozygote | In HWEChi-squarea | Significance level p | Deviation from HWEChi-squarea | Significance level p | |

| Gene | p21 (CDKN1A) codon 31 C>A Ser/Arg | ||||||

| Cancer patients | |||||||

| Observed # | 87 | 61 | 8 | 0.42 | NSb | 0.52 | NSb |

| Expected # | 88.5 | 58 | 9.5 | ||||

| Control individuals | |||||||

| Observed # | 166 | 77 | 8 | 0.07 | NSb | 0.80 | NSb |

| Expected # | 166.6 | 75.8 | 8.6 | ||||

| Gene | Ku80 untranslated mRNA 2790 A/G | ||||||

| Cancer patients | |||||||

| Observed # | 119 | 32 | 5 | 2.23 | NSb | 0.14 | NSb |

| Expected # | 116.8 | 36.3 | 2.8 | ||||

| Control individuals | |||||||

| Observed # | 164 | 79 | 8 | 0.17 | NSb | 0.68 | NSb |

| Expected # | 165 | 77 | 9 | ||||

| Gene MDM2 promoter 309 T/G | |||||||

| Cancer patients | |||||||

| Observed # | 69 | 61 | 26 | 3.68 | NSb | 0.05 | NSb |

| Expected # | 63.5 | 72.1 | 20.5 | ||||

| Control individuals | |||||||

| Observed # | 67 | 120 | 64 | 0.48 | NSb | 0.49 | NSb |

| Expected # | 64.3 | 125.5 | 61.3 | ||||

Pearson's chi-square at 1 degree of freedom.

NS, not significant (the 5% significance level for 1 degree of freedom is ≥3.84).

HWE, Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium.

Discussion

Genetic predisposition to head and neck cancer is a contributing factor to smoking, environmental and occupational exposures, and interaction with oncogenenic viral infections (Siemiatycki et al., 2004; Hashibe et al., 2007; Ho et al., 2007; Chung and Gillison, 2009). In this association study, we investigated the role of 10 polymorphisms in genes involved in cell cycle and DNA repair pathways as risk factors for head and neck cancer occurrence (Fig. 2). Overall, results showed significant associations for p21 C31A (p=0.04), Ku80 A2790G (p=0.04), and MDM2 T309G (p=0.0003) with head and neck cancer occurrence. In contrast, no statistically significant association was found for p53 G72C, ATM G1853A, XRCC1 G399A, XRCC3 C241T, DNA Ligase IV C9T, DNA-PKcs A3434G, and TGF-beta T10C at allele or genotype level.

The p21 protein is induced by p53 in response to DNA damage caused by exposure to environmental carcinogens and acts as cell cycle inhibitor to arrest cell growth to allow DNA repair (Powell et al., 2002). Therefore, p21 polymorphism was suggested to affect cancer risk, and several studies have correlated the p21 codon 31 SNP with various human malignancies, including colorectal cancer (Shiohara et al., 1994), soft tissue sarcoma (Mousses et al., 1995), breast cancer (Lukas et al., 1997), prostate cancer (Huang et al., 2004), and HNSCC (Facher et al., 1997). Results presented here showed that the p21 codon 31 variant allele A was associated with increasing risk to develop head and neck cancer in Saudi Arabia. These results are in line with those found by Facher et al. (1997), who reported an association between the p21 codon 31 variant allele A and increasing risk of prostate adenocarcinoma and HNSCC.

The Ku80 gene, also known as XRCC5, is an important and specific member of the nonhomologous end joining (NHEJ) DNA repair pathway. In NHEJ, Ku80 protein works along with Ku70 to form a unique dimer, which acts as a regulatory subunit of the DNA-dependent protein kinase (DNA-PK) complex by increasing the affinity of the catalytic subunit to DNA. Ku80 is very important in removing DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) and its genetic variations probably influence its normal function or expression level and the overall efficiency of NHEJ. Genetic polymorphic variations in DNA DSB repair genes have been associated with variety of cancers including head and neck cancers (Bau et al., 2004; Chiu et al., 2008; Hsu et al., 2009). The Ku80 A2790G polymorphism (rs1051685) is located in the untranslated region of the gene and this is the first study that attempted to associate this SNP with cancer risk. Our results showed that the variant G allele of Ku80 2790 SNP was associated with head and neck cancer development (p=0.04; OR=1.5; CI: 1.01–2.23).

MDM2, an important negative regulator of p53, forms a negative autoregulatory feedback loop with p53. First, MDM2 may directly bind to the tumor suppressor p53 and inhibit p53-mediated transactivation (Momand et al., 1992; Oliner et al., 1993). Second, MDM2 functions as an E3 ubiquitin ligase, responsible for the ubiquitination and degradation of p53 (Haupt et al., 1997; Kubbutat et al., 1997). Most studies in different types of cancer found that the G allele increases risk for cancer development (Hu et al., 2007; Yang et al., 2007; Zhou et al., 2007). However, several studies found no association between the MDM2 promoter 309 G variant allele with cancer risk (Ma et al., 2006; Millikan et al., 2006; Schmidt et al., 2007). In contrast, our study found that the G variant allele is highly significant (p=0.0003) with decreasing risk to cancer occurrence in line with other studies (Li et al., 2006; Phang et al., 2008).

The reason behind the inconsistency between the various studies is unknown. However, the frequency of MDM2 309 G allele is variable between different races and ethnic groups. Our result presented here showed an intermediate frequency of 0.44 for the MDM2 309 G allele (which is in HWE), between that of the Chinese population (above 0.50) and the Caucasian (<0.40) (Bond et al., 2004; Hu et al., 2006; Ma et al., 2006). These variations between populations might influence the interpretation of the association between MDM2 SNP309 and cancer occurrence susceptibility. In addition, the genotype frequencies of the three SNPs (p21 C31A, Ku80 A2790G, and MDM2 T309G) which showed statistically significant association with head and neck cancer, were in HWE (at 5% significance level for 1 degree of freedom; Table 3). Further, testing for deviation from HWE showed that the differences between expected and observed genotypes' counts were not statistically significant (Table 3). Therefore, the null hypothesis that the population is in Hardy–Weinberg frequencies is not rejected. Although there is a widely held belief that our population has a high level of consanguinity, these results suggest that there is random mating, no selection, no gene flow, and a population large enough to avoid the random effects of genetic drift in our study.

In conclusion, the p21 C31A, Ku80 A2790G, and MDM2 T309G genetic polymorphic variations are associated with the occurrence of head and neck cancer in the Saudi population. These SNPs could be used as genetic biomarkers to screen individuals at high cancer risk.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. M. El-Sebaie, Dr. N. Alrajhi, Ms. M. Al-Buhairi, and Ms. L. Aubrey Venturina for helping in sample collection, Dr. B. Meyer, Mr. M. Rajab, and the KFSH&RC Sequencing Core Facility for helping in DNA sequencing, and Dr. B. Moftah and members of the Biomedical Physics Department for their support. This work was funded by KFSHRC (grant numbers 2000 031 and 2040 025).

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- Alsbeih G. Al-Harbi N. Al-Hadyan K, et al. Association between normal tissue complications after radiotherapy and polymorphic variations in TGFB1 and XRCC1 genes. Radiat Res. 2010;173:505–511. doi: 10.1667/RR1769.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Authority NCR. Cancer Incidence Report: Saudi Arabia, Ministry of Health, Saudi Cancer Registry. 2006.

- Bau DT. Fu YP. Chen ST, et al. Breast cancer risk and the DNA double-strand break end-joining capacity of nonhomologous end-joining genes are affected by BRCA1. Cancer Res. 2004;64:5013–5019. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bettendorf O. Piffko J. Bankfalvi A. Prognostic and predictive factors in oral squamous cell cancer: important tools for planning individual therapy? Oral Oncol. 2004;40:110–119. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2003.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bond GL. Hu W. Bond EE, et al. A single nucleotide polymorphism in the MDM2 promoter attenuates the p53 tumor suppressor pathway and accelerates tumor formation in humans. Cell. 2004;119:591–602. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brookes AJ. The essence of SNPs. Gene. 1999;234:177–186. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(99)00219-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu CF. Wang CH. Wang CL, et al. A novel single nucleotide polymorphism in XRCC4 gene is associated with gastric cancer susceptibility in Taiwan. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:514–518. doi: 10.1245/s10434-007-9674-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung CH. Gillison ML. Human papillomavirus in head and neck cancer: its role in pathogenesis and clinical implications. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:6758–6762. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Facher EA. Becich MJ. Deka A. Law JC. Association between human cancer and two polymorphisms occurring together in the p21Waf1/Cip1 cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor gene. Cancer. 1997;79:2424–2429. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19970615)79:12<2424::aid-cncr19>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashibe M. Brennan P. Benhamou S, et al. Alcohol drinking in never users of tobacco, cigarette smoking in never drinkers, and the risk of head and neck cancer: pooled analysis in the International Head and Neck Cancer Epidemiology Consortium. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99:777–789. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djk179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haupt Y. Maya R. Kazaz A. Oren M. Mdm2 promotes the rapid degradation of p53. Nature. 1997;387:296–299. doi: 10.1038/387296a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho T. Wei Q. Sturgis EM. Epidemiology of carcinogen metabolism genes and risk of squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Head Neck. 2007;29:682–699. doi: 10.1002/hed.20570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu CF. Tseng HC. Chiu CF, et al. Association between DNA double strand break gene Ku80 polymorphisms and oral cancer susceptibility. Oral Oncol. 2009;45:789–793. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2008.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Z. Jin G. Wang L, et al. MDM2 promoter polymorphism SNP309 contributes to tumor susceptibility: evidence from 21 case-control studies. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16:2717–2723. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Z. Ma H. Lu D, et al. Genetic variants in the MDM2 promoter and lung cancer risk in a Chinese population. Int J Cancer. 2006;118:1275–1278. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang SP. Wu WJ. Chang WS, et al. p53 Codon 72 and p21 codon 31 polymorphisms in prostate cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2004;13:2217–2224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubbutat MH. Jones SN. Vousden KH. Regulation of p53 stability by Mdm2. Nature. 1997;387:299–303. doi: 10.1038/387299a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G. Zhai X. Zhang Z, et al. MDM2 gene promoter polymorphisms and risk of lung cancer: a case-control analysis. Carcinogenesis. 2006;27:2028–2033. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgl047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukas J. Groshen S. Saffari B, et al. WAF1/Cip1 gene polymorphism and expression in carcinomas of the breast, ovary, and endometrium. Am J Pathol. 1997;150:167–175. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma H. Hu Z. Zhai X, et al. Polymorphisms in the MDM2 promoter and risk of breast cancer: a case-control analysis in a Chinese population. Cancer Lett. 2006;240:261–267. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2005.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millikan RC. Heard K. Winkel S, et al. No association between the MDM2-309 T/G promoter polymorphism and breast cancer in African-Americans or Whites. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15:175–177. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Momand J. Zambetti GP. Olson DC, et al. The mdm-2 oncogene product forms a complex with the p53 protein and inhibits p53-mediated transactivation. Cell. 1992;69:1237–1245. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90644-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mousses S. Ozcelik H. Lee PD, et al. Two variants of the CIP1/WAF1 gene occur together and are associated with human cancer. Hum Mol Genet. 1995;4:1089–1092. doi: 10.1093/hmg/4.6.1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliner JD. Pietenpol JA. Thiagalingam S, et al. Oncoprotein MDM2 conceals the activation domain of tumour suppressor p53. Nature. 1993;362:857–860. doi: 10.1038/362857a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkin DM. Bray F. Ferlay J. Pisani P. Global cancer statistics, 2002. CA Cancer J Clin. 2005;55:74–108. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.55.2.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phang BH. Linn YC. Li H. Sabapathy K. MDM2 SNP309 G allele decreases risk but does not affect onset age or survival of Chinese leukaemia patients. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44:760–766. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell BL. van Staveren IL. Roosken P, et al. Associations between common polymorphisms in TP53 and p21WAF1/Cip1 and phenotypic features of breast cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2002;23:311–315. doi: 10.1093/carcin/23.2.311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt MK. Reincke S. Broeks A, et al. Do MDM2 SNP309 and TP53 R72P interact in breast cancer susceptibility? A large pooled series from the breast cancer association consortium. Cancer Res. 2007;67:9584–9590. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiohara M. el-Deiry W. Wada M, et al. Absence of WAF1 mutations in a variety of human malignancies. Blood. 1994;84:3781–3784. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siemiatycki J. Richardson L. Straif K, et al. Listing occupational carcinogens. Environ Health Perspect. 2004;112:1447–1459. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang M. Guo Y. Zhang X, et al. Interaction of P53 Arg72Pro and MDM2 T309G polymorphisms and their associations with risk of gastric cardia cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2007;28:1996–2001. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgm168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou G. Zhai Y. Cui Y, et al. MDM2 promoter SNP309 is associated with risk of occurrence and advanced lymph node metastasis of nasopharyngeal carcinoma in Chinese population. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:2627–2633. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]