SUMMARY

Specialized somatosensory neurons detect temperatures ranging from pleasantly cool or warm to burning hot and painful (nociceptive). The precise temperature ranges sensed by thermally sensitive neurons is determined by tissue specific expression of ion channels of the Transient Receptor Potential (TRP) family. We show here, that in Drosophila, TRPA1 is required for sensing of nociceptive heat. We identify two new protein isoforms of dTRPA1named dTRPA1-C and dTRPA1-D that explain this requirement. A dTRPA1-C/D reporter was exclusively expressed in nociceptors and dTRPA1-C rescued thermal nociception phenotypes when restored to mutant nociceptors. However, surprisingly, we find that dTRPA1-C is not a direct heat sensor. Alternative splicing generates at least four isoforms of dTRPA1. Our analysis of these isoforms reveals a 37 amino acid intracellular region (encoded by a single exon) that is critical for dTRPA1 temperature responses. The identification of these amino acids opens the door to a biophysical understanding of a molecular thermosensor.

INTRODUCTION

Nociception is the sensorineural process of encoding noxious stimuli. The ability to sense and avoid potential or actual tissue damaging stimuli, such as noxious temperature, mechanical stimuli and irritant chemicals, is critical for survival. Transient receptor potential (TRP) channels have been shown to play an important role in a variety of sensory systems. Several members of this family have been shown to be involved in nociception (Bautista et al., 2006; Caterina et al., 2000; Kwan et al., 2006).

In mammals, TRPA1 has been implicated as a key player in nociception. The recent identification of a mutation in TRPA1 that is associated with a heritable Familial Episodic Pain Syndrome (FEPS) in a Colombian family represents the first human pain-related syndrome to be linked to the TRP gene superfamily (Kremeyer et al., 2010; Waxman, 2010). In mice, TRPA1 is detected in a subset of TRPV1-expressing dorsal root ganglion (DRG) C fibers and Aδ fibers, which are the nociceptive afferents. TRPA1 has been found to be required for chemical, mechanical and noxious cold nociception, although the latter remains controversial (Bautista et al., 2006; Brierley et al., 2011; Jordt et al., 2004; Kwan et al., 2006; Story et al., 2003). The TRPA1 channel is activated by many irritant chemicals, such as cinnamaldehyde, allyl isothiocyanate (AITC) (mustard oil), allicin (garlic) and acrolein (tear gas) (Bautista et al., 2006; Bautista et al., 2005). Many of these chemicals are reactive electrophiles that are thought to activate TRPA1 through covalent modification of cysteines (Bautista et al., 2006; Macpherson et al., 2007). Indeed, TRPA1 knockout mice show profound defects in avoiding these normally noxious compounds (Bautista et al., 2006; Kwan et al., 2006).

Two recent studies have now shown that Drosophila TRPA1 (dTRPA1) is required for thermal nociception (Babcock et al., 2011; Neely et al., 2011) in both larvae and in adult flies. The findings of these studies are surprising because the temperature threshold of the dTRPA1 thermoTRP channel (27°C) does not match the temperature threshold for baseline nociception (39°C). In addition, dTRPA1 reporters are not expressed in nociceptive neurons which leaves the site of action for dTRPA1 in nociception pathways unclear.

Here, using a newly isolated null mutant allele of dTRPA1 we further demonstrate that dTRPA1 indeed plays a role in thermal and mechanical nociception. We have identified transcripts encoding previously unknown isoforms of dTRPA1 (named dTRPA1-C and dTRPA1-D) that have distinct biophysical properties from the canonical dTRPA1-A isoform. A transgenic reporter for dTRPA1-C and D is specifically expressed in the nociceptors of Drosophila larvae. Expression of dTRPA1-C isoform in heterologous cells suggests that it is not a direct temperature sensor at temperatures as high as 42°C, but it does respond to isothiocyanate compounds. Nevertheless, expression of dTRPA1-C in nociceptors rescued thermal nociception phenotypes of dTrpA1 mutants. Our results suggest a role for dTRPA1 in thermal nociception that does not depend on thermosensitivity. Furthermore, analysis of the four existing dTRPA1 isoforms reveals 37 intracellular amino acids (between the last ankryin repeat and membrane spanning segment S1) as playing a critical role temperature sensing. Sequences at the absolute N-terminus also affect temperature responses. The identification of these heat responsive elements, which we term TACs, will enable a biophysical understanding of heat sensing by TRPA1 channels.

Results and Discussion

Identification of a chemically induced dTrpA1 functional null mutant allele

We performed a screen for ethyl methanesulfonate (EMS)-induced mutations of the dTrpA1 locus through the Drosophila Tilling Project (Cooper et al., 2008). One line stood out as a potential null loss-of-function allele of dTrpA1. As in all TRP channels, dTRPA1 is predicted to have six transmembrane domains with a pore loop between the fifth and sixth transmembrane domain. In the EMS-induced mutant allele dTRPA1W903*, a guanosine is mutated to an adenosine (Figure S1), changing the codon for Tryptophan 903 to a premature amber stop codon. As this residue was located upstream of the pore loop, the premature stop codon located in the fourth transmembrane domain of dTrpA1 was predicted to lead to the production of a non-functional dTRPA1 channel from all possible dTRPA1 transcripts (Figure 1A). In addition, Df(3L)ED4415, a deficiency removing 210 kb that included dTrpA1 (as well as 25 other genes), was available for our studies. As expected for a large deficiency, Df(3L)ED4415 is not homozygous viable. In order to separate the dTrpA1W903*mutation from other unlinked EMS-induced mutations that might be present in the mutagenized strain, we out-crossed the dTrpA1W903* mutant chromosome to the Df(3L)ED4415 strain for six generations.

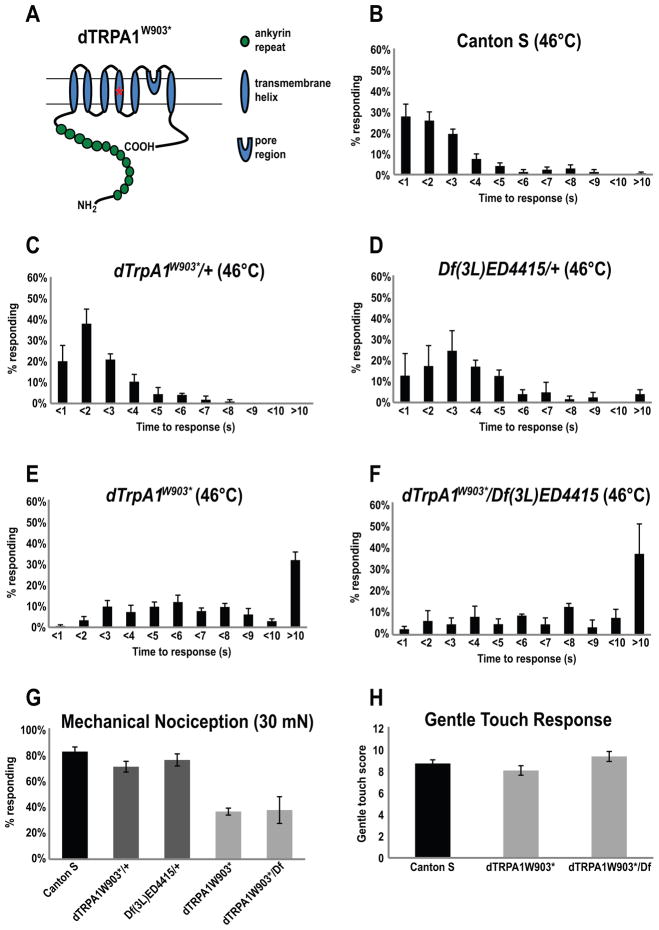

Figure 1. dTrpA1 is required for thermal and mechanical nociception.

(A) Schematic diagram of dTRPA1 protein. Green circles indicate ankyrin repeats, while blue ovals indicate transmembrane helices. Asterisk indicates location of the premature stop codon in dTrpA1W903*.

(B–F) The distribution of NEL latency for wandering third-instar larvae stimulated with a 46°C probe.

(B) The distribution of thermal nociception responses of wild type Canton S larvae (4 trials, n=115).

(C) The distribution of thermal nociception responses of dTrpA1W903*/+ larvae (3 trials, n=80) resembled wild type Canton S (Wilcoxon rank-sum test with Bonferroni correction, p>0.9).

(D) The latencies for thermal nociception responses of Df(3L)ED4415/+ larvae (3 trials, n=54) are slightly delayed compared to wild type (Wilcoxon rank-sum test with Bonferroni correction, p<0.01).

(E) dTrpA1W903* mutant larvae (4 trials, n=149) showed severely delayed nociception responses in comparison to control strains Canton S and dTrpA1W903*/+ (Wilcoxon rank-sum test with Bonferroni correction, p<0.0001).

(F) dTrpA1W903*/Df(3L)ED4415 larvae (3 trials, n=67) showed delayed NEL in comparison to control strains Canon S, dTrpA1W903*/+ and Df(3L)ED4415/+, indicating that Df(3L)ED4415 failed to complement the NEL defects of dTrpA1W903* (Wilcoxon rank-sum test with Bonferroni correction, p<0.0001).

(G) dTrpA1 is required for mechanical nociception. A significantly reduced proportion of dTrpA1W903* (3 trials, n= 97, Pearson’s Chi-square Test for Independence with Bonferroni correction, p<0.001(***) in comparison to Canton S or dTrpA1W903*/+ ) and dTrpA1W903*/Df(3L)ED4415 (3 trials, n=80 Pearson’s Chi-square Test for Independence with Bonferroni correction, p<0.001(***) in comparison to Canton S and Df(3L)ED4415/+ or dTrpA1W903*/+) larvae showed NEL responses to 30 mN Von Frey Fibers relative to wild type Canton S larvae (5 trials, n=120), dTrpA1W903*/+ heterozygous (3 trials, n=63) and Df(3L)ED4415/+ heterozygous (3 trials, n=67) animals.

(H) The average summed gentle touch response scores of wild type Canton S (n=28), dTrpA1 mutants dTRPA1W903* (n=16) and dTRPA1W903*/Df(3L)ED4415 (n=21) were not significantly different (single factor ANOVA, p=0.13).

In figures (B) through (H), error bars indicate the SEM.

dTrpA1 mutants are defective for both thermal and mechanical nociception

We found that the out-crossed dTrpA1W903* mutant animals showed pronounced defects in behavioral assays for nociception. Drosophila larvae produce stereotyped nocifensive escape locomotion (NEL) behavior in response to noxious thermal or mechanical stimuli (Hwang et al., 2007; Wheeler et al., 2002; Zhong et al., 2010). Wild-type animals gently touched with a 46°C probe initiate NEL behavior within 3 seconds (Figure 1B) (Babcock et al., 2009; Hwang et al., 2007; Tracey et al., 2003). In contrast, we observed that dTrpA1W903* mutant larvae displayed a significantly delayed response. Many of the mutants failed to initiate the escape behavior within 10 seconds (Figure 1E). The heterozygous dTrpA1W903*/+ larvae showed normal responses to noxious heat and Df(3L)ED4415/+ larvae had only mild defects (Figures 1C and 1D), indicating a recessive mutant phenotype (Figure 1C). The mutant phenotype mapped to the dTrpA1 locus, as Df(3L)ED4415 failed to complement dTrpA1W903* (Figure 1F).

We also tested the dTrpA1 mutants for mechanical nociception responses (Figure 1G). Compared to wild type and heterozygous controls, which produced robust nocifensive responses to stimulation with a 30 mN von Frey fiber, both the dTrpA1W903* and dTrpA1W903*/Df(3L)ED4415 larvae were significantly less responsive (Figure 1G). This decreased response was specific to mechanical nociception, as dTrpA1 mutant larvae showed normal responses to gentle touch (Figure 1H). In addition, gross motor functions of dTrpA1 mutants appeared normal (data not shown) (Rosenzweig et al., 2005).

A 21 kb piece of genomic DNA that included the entire dTrpA1 locus (and the neighboring gene, mcm7) completely rescued the dTrpA1 thermal and mechanical nociception defects (Figure 2A and 2E). This further narrowed down the genetic aberration causing the nociception defects of the mutant to one of two genes, dTrpA1 and mcm7.

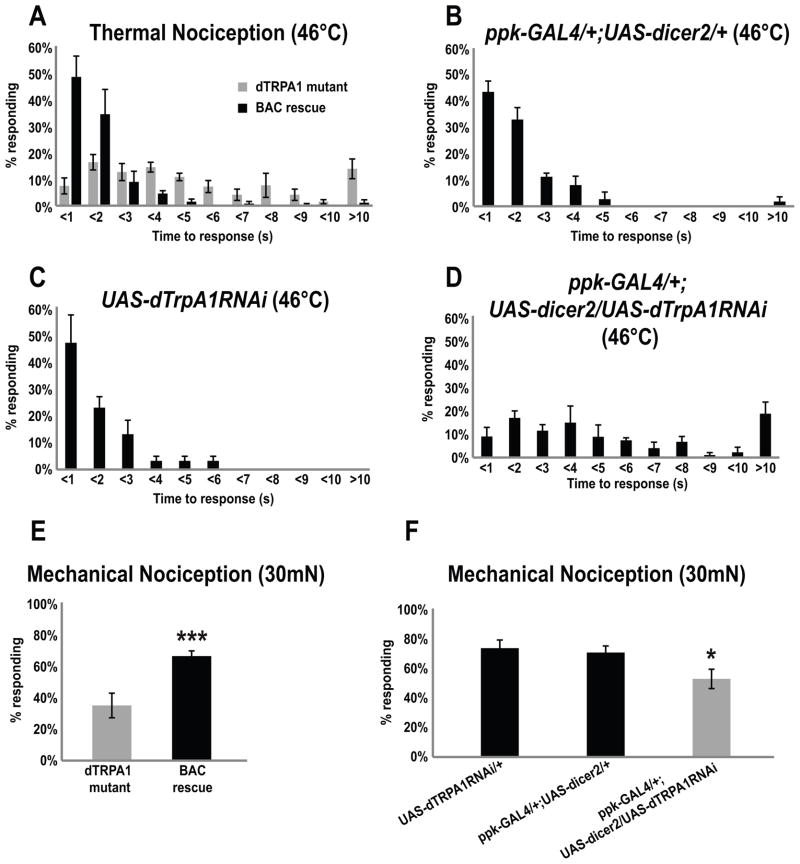

Figure 2. Genomic rescue of dTrpA1 and nociceptor specific RNAi knockdown of dTrpA1.

(A) In the thermal nociception assay the dTrpA1-BAC/+; dTrpA1W903*/Df(3L)ED4415 larvae (3 trials, n=143) showed rescued nocifensive behavior resembling the wild type while dTrpA1W903*/Df(3L)ED4415 mutants tested side by side still showed delayed responses (3 trials, n=180) (Wilcoxon rank-sum test, p<0.01).

(B, C, D) The nociception responses of larvae with dTrpA1RNAi knockdown in mdIV neurons (ppk-GAL4/+; UAS-dicer2/UAS-dTrpA1RNAi, 3 trials, n=112) are significantly delayed compared to the control groups (ppk-GAL4/+; UAS-dicer2/+, 3 trials, n=113; UAS-dTrpA1RNAi/+, 3 trials, n=49) (Wilcoxon rank-sum test with Bonferroni correction, p<0.0001).

(E) In the mechanical nociception assay, dTrpA1-BAC/+; dTrpA1W903*/Df(3L)ED4415 larvae (3 trials, n=139) showed rescued nociception responses upon stimulation with a 30 mN mechanical force relative to dTrpA1W903*/Df(3L)ED4415 mutants (3 trials, n=111, Pearson’s Chi-square Test for Independence with Bonferroni correction, p<0.001(***)).

(F) Nociceptor specific knockdown in dTrpA1RNAi larvae (ppk-GAL4/+; UAS-dicer2/UAS-dTrpA1RNAi, n=124) showed reduced mechanical nociception responses to a 30 mN mechanical force compared control strains that had driver alone (ppk-GAL4/+; UAS-dicer2/+, n=110) or UAS-dTrpA1 without the driver (UAS-dTrpA1RNAi/+, n=84) (Pearson’s Chi-square Test for Independence with Bonferroni correction, p<0.01(**) in comparison to UAS-dTrpA1RNAi/+; p<0.05(*) in comparison to ppk-GAL4/+; UAS-dicer2/+.)

In figures (A) through (G), error bars indicate the SEM.

RNAi knockdown of dTrpA1 expression in mdIV neurons phenocopies the mutant

The class IV multidendritic (mdIV) neurons function as polymodal nociceptors in Drosophila larvae (Hwang et al., 2007). These neurons are known to respond in extracellular recordings to AITC in a dTRPA1 dependent manner(Xiang et al., 2010). Yet, previously existing dTrpA1 reporters are not expressed in these cells (Hamada et al., 2008; Rosenzweig et al., 2005) (WDT and LZ unpublished observations). Thus, to test whether dTrpA1 was required in the nociceptors for mechanical and thermal nociception, we used the nociceptor specific pickpocket1.9-GAL4 (ppk-GAL4) driver to express UAS-dTrpA1-RNAi and UAS-dicer2 (Hwang et al., 2007). The ppk-GAL4/+; UAS-dTrpA1RNAi/UAS-dicer2 larvae showed reduced responses to both noxious thermal and mechanical stimuli (Figures 2D and 2F). Although RNAi mutant phenotypes were less severe than those of the genetic null mutant, these results support the involvement of dTRPA1 in nociception and further suggest that the site of action for dTrpA1 is in the nociceptors themselves.

Properties of the known isoforms of dTrpA1 are not consistent with a function in nociception

The heat activation threshold of the known heat sensing dTRPA1-A ion channel is between 24°C and 29°C (Viswanath et al., 2003). In contrast, both the behavioral threshold for larval nociception and the activation threshold of the mdIV neurons are approximately 39°C (Tracey et al., 2003; Xiang et al., 2010). Thus, although our behavioral results, as well as the recent results of others(Babcock et al., 2011), suggested a site of action for dTrpA1 in nociceptors, the known biophysical properties of dTRPA1-A seemed inconsistent with this possibility.

If dTRPA1-A was expressed in nociceptors then the predicted behavioral threshold for nociception would be 29°C. Indeed, consistent with this prediction, larvae with forced expression of the dTrpA1-A isoform in the nociceptor neurons (ppk-GAL4/+; UAS-dTrpA1-A/+) had a dramatically lowered thermal nociception threshold. Greater than ninety percent of these larvae responded to a 30°C heat stimulus with NEL in less than one second (Figure 3). This was in dramatic contrast to the behavior of wildtype larvae and other control genotypes, which never produced NEL in response to 30°C heat (Figure 3). The behavior of larvae expressing dTRPA1-A in nociceptors causes thermal allodynia that is even more severe, and with a lower threshold (<30°C), than that which is seen following exposure of larvae to tissue damaging UV-C radiation (which causes a behavioral thermal nociception threshold of 34°C (Babcock et al., 2009)).

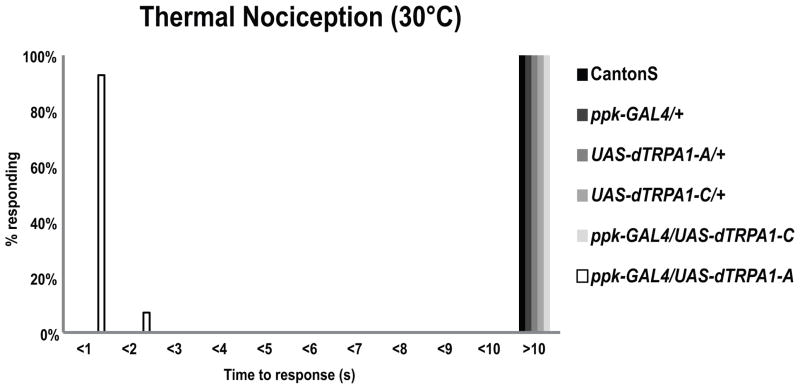

Figure 3. Expression of dTRPA1-A, but not dTRPA1-C, in mdIV neurons lowers the thermal nociception threshold.

Wild type Canton S larvae (n=86), UAS-dTrpA1-A/+ larvae (n=54), ppk-GAL4/+ larvae (n=37), UAS-dTRPA1-C/+ larvae (n=30) and ppk-GAL4/UAS-dTRPA1-C larvae (n=30) did not show nocifensive responses to 30°C stimuli within 10 seconds. However, ppk-GAL4/UAS-dTrpA1-A larvae (n=28) showed robust nocifensive responses to 30°C stimuli with most of the larvae responding within 1 second (Wilcoxon rank-sum test with Bonferroni correction, p<0.0001 in comparison to all other groups).

Several important conclusions can be drawn from these results. First, the results further confirmed that mdIV neurons are indeed nociceptors, since expression of dTrpA1-A in mdIV neurons altered the thermal threshold of NEL behavior in an intuitively predictable manner. Second, the results argued against a role for dTRPA1-A in mediating baseline nociception in the mdIV neurons. This is in apparent conflict with the results of dTrpA1 mutant behavior, genomic rescue, and RNAi knockdown experiments, which strongly suggest that dTrpA1 is required in mdIV neurons for nociception. Furthermore, since existing dTrpA1 reporters are not expressed in mdIV neurons, another known isoform of dTrpA1 (dTrpA1-B, Figure 4B), which shares a transcription start site with dTrpA1-A (Kwon et al., 2010), could not explain the requirement for dTRPA1 in nociception behaviors.

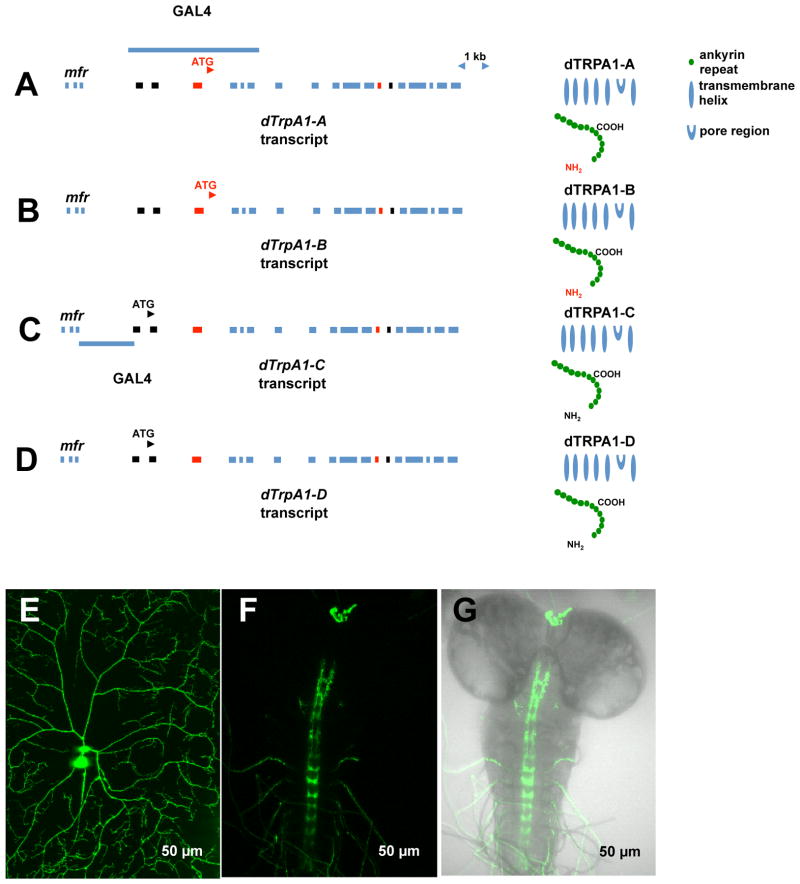

Figure 4. Gene and protein structures of four isoforms of dTrpA1 and the dTrpA1-C/D expression pattern.

(A) Gene and protein structures of the canonical warmth-activated dTrpA1-A isoform. The dTRPA1-A first exon and alternatively spliced 12th exon are labeled in red. The blue bar located above the gene illustrates the region of DNA sequence used for making a previous described dTrpA1-A-GAL4 reporter (Hamada et al., 2008). The dTRPA1-A protein is predicted to have six transmembrane domains with 13 ankyrin repeats at the N-terminus (Viswanath et al., 2003). The regions marked in red on the protein schematic are encoded by the red-labeled exons in the gene structure diagram.

(B) Gene and protein structures of the dTrpA1-B isoform. The dTrpA1-B isoform uses the first exon of dTrpA1-A (red) and is alternatively spliced to include the 13th exon (black). The red-and black-labeled regions flanking the ankyrin repeats in the protein schematic are encoded by the red exon 3 and black exon 13 in the gene structure diagram.

(B) The newly cloned isoform, dTRPA1-C, which uses a novel start site to include two 5′ exons marked in black (exons 1 and 2) and is alternatively spliced to include the 13th exon (black). The blue bar below the gene illustrates the intergenic region between the neighboring gene mfr and dTrpA1-C isoform used for making dTrpA1-C/D-GAL4 reporter. The black-labeled regions flanking the ankyrin repeats in the protein schematic are encoded by the black exons in the gene structure diagram.

(D) Gene and protein structures of the dTrpA1-D isoform. The dTrpA1-D isoform uses the exons 1 and 2 (black) and is alternatively spliced to include the 13th exon (red). The red-and black-labeled regions flanking the ankyrin repeats in the protein schematic are encoded by the black exons 1 and 2 and red exon 13 in the gene structure diagram.

(E) dTrpA1-C/D-GAL4 showed specific expression in larval mdIV neurons. The image is a maximum-intensity projection of a dorsal mdIV neuron (ddaC) (dTrpA1-Gal4≫UAS-mCD8GFP, third instar). (F) CNS expression pattern of dTrpA1-C/D-Gal4≫UAS-mCD8GFP (third instar). Expression is specific to the projections of mdIV neurons. In the body wall, expression of dTRPA1-C/D-GAL4 was also seen in multidendritic bipolar (md-bp) neurons. Bipolar neuron projections from anterior segments and potential ring gland expression were also observed. (G) Merged image of brain expression of dTrpA1-C/D-GAL4≫UAS-mCD8GFP with brightfield CNS.

Cloning of new dTrpA1 isoforms

A potential explanation for these findings was found when we examined the genomic region surrounding the dTrpA1 locus and identified two highly conserved putative exons that were located upstream of the known transcriptional start site for dTrpA1-A and dTrpA1-B. These exons were historically annotated as part of the misfire (mfr) gene (WDT and LZ unpublished observation) and this may have caused them to be unnoticed in earlier studies. Current annotations predict that these exons may be part of the dTrpA1 locus and spliced into the first exon of dTrpA1-A/B. To test the possibility that the novel exons were indeed part of the dTRPA1 locus we performed the reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). We successfully amplified, cloned, and sequenced PCR products from these reactions, identifying two novel dTrpA1 transcripts (Supplemental Figure S2A and S2B). To distinguish these transcripts from the known transcripts of dTrpA1 (dTrpA1-A and dTrpA1-B)(Figure 4A,B), we refer to the newly identified transcripts as dTrpA1-C and dTrpA1-D (Figure 4C,D).

The novel transcripts are distinct from the dTrpA1-A and dTrpA1-B transcripts. They are also distinct from other dTrpA1 transcripts that have been predicted to exist by the Drosophila genome project because they do not include the third exon of the annotated dTrpA1 locus (Figure 4A–D). The DNA sequence of plasmid clones of dTrpA1-C and dTrpA1-D confirmed the incorporation of the two upstream exons into novel dTrpA1 transcriptional start and splice variants. Alternative splicing of dTrpA1-C and dTrpA1-D results in skipping of the initial exon (the third exon of the locus) that is used in dTrpA1-A/B transcripts (Figure 4C,D). In contrast to the genome annotation, direct sequencing of PCR products used in cloning experiments indicated that the third exon of the locus was not spliced into the first or second exons at detectable levels (data not shown).

In addition, two alternatively spliced downstream exons exist in the four transcripts. The 12th exon of dTrpA1 is shared in the dTrpA1-A and dTrpA1-D transcripts (Figure 4A and 4D) and the 13th exon of the locus is shared between dTrpA1-B and dTrpA1-C (Figure 4B and 4C).

Four distinct proteins are predicted from these transcripts. At the dTRPA1-C/D N-termini, 97 amino acids are encoded by exons 1 and 2 and these amino acids do not share sequence similarity with the first 62 amino acids that are encoded by the first exon of dTrpA1-A/B (Supplemental Figure S2C). In addition, the alternatively spliced 13th exon that is shared between dTrpA1-B and dTrpA1-C encodes 36 amino acids that are not easily aligned with 37 amino acids that are encoded by the shared exon 12 of dTrpA1-A and dTrpA1-D (Supplemental Figure S2D). It is important to note that the amino acid variants of the protein do not change ankyrin repeats per se. Rather, the alternate amino acids flank the ankyrin repeats at the very N-terminus and immediately following the last ankyrin repeat (Figure 4C and 4D).

Nociceptive neurons express dTRPA1-C and require it for nociception

As noted above, existing GAL4 reporter strains for dTrpA1-A/B (Hamada et al., 2008; Rosenzweig et al., 2005; Tian et al., 2009) are not expressed in the mdIV nociceptive neurons (WDT and LZ unpublished observation). However, these reporters were made utilizing genomic DNA from regions largely downstream of the transcriptional start site of dTrpA1-C/D and they thus likely lack important upstream enhancer elements for dTrpA1-C/D (Figure 4B). Therefore, to investigate the expression pattern of dTrpA1-C/D, we cloned the 2.1 kb genomic interval between the transcriptional start site of dTrpA1-C/D and the 3′ end of misfire into a GAL4 reporter transformation vector and generated transgenic GAL4 reporter fly strains (Figure 4B). Remarkably, dTrpA1C/D-GAL4 driving expression of UAS-mCD8GFP showed nearly exclusive mCD8GFP expression in the larval mdIV nociceptors and their central projections (Figure 4E, 4F and 4G). This expression pattern led us to further hypothesize that either dTRPA1-C or dTRPA1-D might be the functional isoform of the mdIV nociceptors. Since the apparent activation temperature of a heterologously expressed dTRPA1-D isoform ((34°C) see below) did not match the baseline thermal nociception threshold of larval nociceptors (39°C) we focused on the possibility that dTRPA1-C was involved in thermal nociception.

In order to directly test the hypothesis that dTRPA1-C was the isoform required for nociception, we generated UAS-dTrpA1-C transgenic flies and performed tissue specific rescue experiments. Driving expression of UAS-dTrpA1-C specifically in the nociceptors (under control of ppk-GAL4) rescued the thermal nociception phenotypes of dTrpA1W903*/Df(3L)ED4415 mutant animals (Figure 5). In addition, in contrast to UAS-dTrpA1-A, expression of UAS-dTrpA1-C did not lower the behavioral threshold for thermal nociception (Figure 3). Combined, these results demonstrate that dTRPA1-C is the important dTRPA1 isoform for Drosophila thermal nociception and that it is required in nociceptors. Furthermore, these results constitute formal genetic proof that the mutation in dTrpA1 is responsible for the noxious heat insensitive phenotype in the dTrpA1W903* mutant strain.

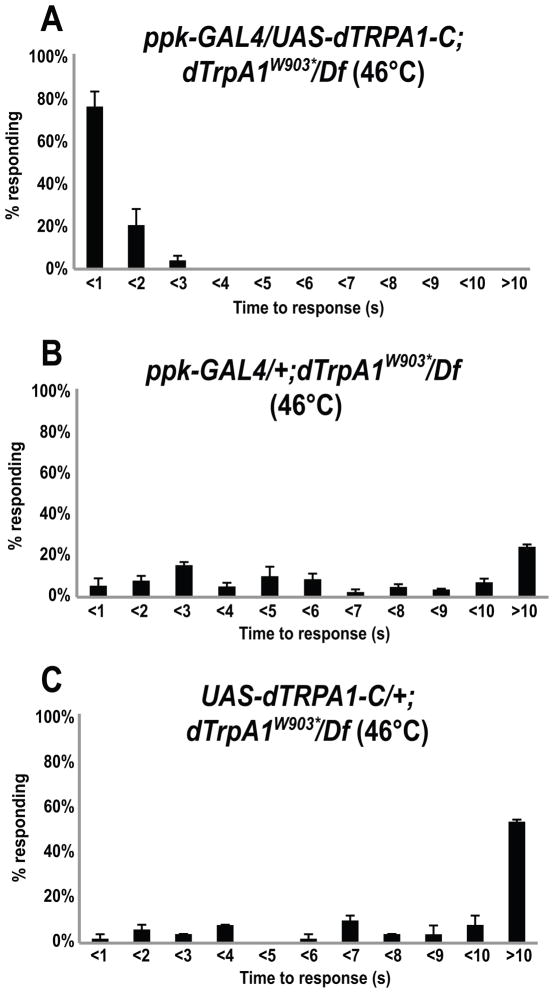

Figure 5. mdIV specific expression of dTRPA1-C rescues thermal nociception defects of dTrpA1 mutants.

(A) Expression of dTrpA1-C specifically in mdIV neurons in dTrpA1 mutant background (ppk-GAL4/UAS-dTrpA1-C; dTrpA1W903*/Df(3L)ED4415) restored thermal nociception behavior (3 trials, n=82). (Wilcoxon rank-sum test with Bonferroni correction, p<0.0001 in comparison to (B) and (C)).

(B) The control, UAS-dTrpA1-C transgene, in the absence of a driver in the mutant background (UAS-dTRPA1-C/+; dTrpA1W903*/Df(3L)ED4415 ) showed the delayed responses to a 46°C stimulus that was typical of the mutant (2 trials, n=51).

(C) The control, ppk-GAL4 driver alone, in the mutant background (ppk-GAL4/+; dTrpA1W903*/Df(3L)ED4415 ) showed the delayed responses to a 46°C stimulus that was typical of the mutant (3 trials, n=83).

In figures (A) through (C), error bars indicate the SEM.

Interestingly, although the dTrpA1 genomic transgene did completely rescue mechanical nociception phenotypes (Figure 2E), dTRPA1-C was not sufficient to rescue mechanical nociception of dTrpA1 mutants when restored to mdIV neurons (LZ and WDT unpublished observations). This suggests that a specific complement of dTRPA1 isoforms is needed for mechanical nociception. It is possible that the dTRPA1-D could be needed for mechanical nociception, or an as yet unidentified isoform could be involved.

TAC elements confer distinct temperature sensing properties to dTRPA1 isoforms

The observation that expression of dTRPA1-A or dTRPA1-C in the mdIV neurons conferred distinct temperature thresholds for the induction of NEL suggested that these two isoforms might have differing biophysical properties. These functional differences may be determined by the amino acids encoded by the alternatively spliced exons. The N-terminal region of dTRPA1 contains a relatively long string of ankyrin repeats that play an unknown role in determining the functional properties of the channel. As mentioned above, the alternate amino acids of dTRPA1-A,B,C and D encode amino acids that flank these repeats (Figure 4A–D). To distinguish the isoform specific sequences from other regions of the dTRPA1 protein, we term these amino acid sequences TRP Ankyrin Caps (TACs). (Figure 4C, D).

To test how the biophysical properties of the newly identified isoforms differ from each other, we developed a novel heterologous expression system. We expressed each isoform, along with the genetically encoded calcium indicator GCaMP3.0 (GCaMP) (Tian et al., 2009), in the Drosophila S2R+ cell line (Yanagawa et al., 1998). We chose to use the Drosophila S2R+ cells for our experiments because the lipid content of the plasma membrane of insect cells is distinct from that of vertebrate cells and we wished to examine the channels in an environment that would closely resemble the situation in vivo. The use of GCaMP in our experiments allowed us to specifically investigate Ca2+ responses of transfected cells. This was important as the transfection efficiency of S2R+ cells was relatively low. Consistent with previous experiments showing that dTRPA1-A is a warmth-activated channel, we observed a dramatic temperature induced increases of GCaMP fluorescence in S2R+ cells transfected with dTRP1-A (Figure 6A, 6B, 6C, 6H and 6I). The majority of cells expressing dTRPA1-A displayed GCaMP fluorescence increases of fifty percent or greater during the heat ramp with an average increase of 122% (Figure 6H and 6I). In contrast, cells transfected with dTRPA1-C did not respond to temperature increases up to 42°C with elevated GCaMP fluorescence (Figure 6D, 6E, 6G, 6H and 6I). The absence of a temperature response in cells expressing dTRPA1-C was not due to dTRPA1-C being a non-functional channel, as a similar proportion of cells expressing dTRPA1-A or dTRPA1-C responded to application of the dTRPA1 agonist allyl isothiocyanate (AITC) (70% and 67%, respectively) with a similar peak response (100% and 125% of baseline, respectively) (Figure 6F, 6G, 6H and 6I). Since the mammalian TRPA1 is activated by cold with a threshold of 17°C, we also tested whether the dTRPA1-C isoform would respond to noxious cold. Within the temperature range of 22-15°C, no Ca2+ responses were detected, suggesting that dTRPA1-C is not sensitive to cold (data not shown).

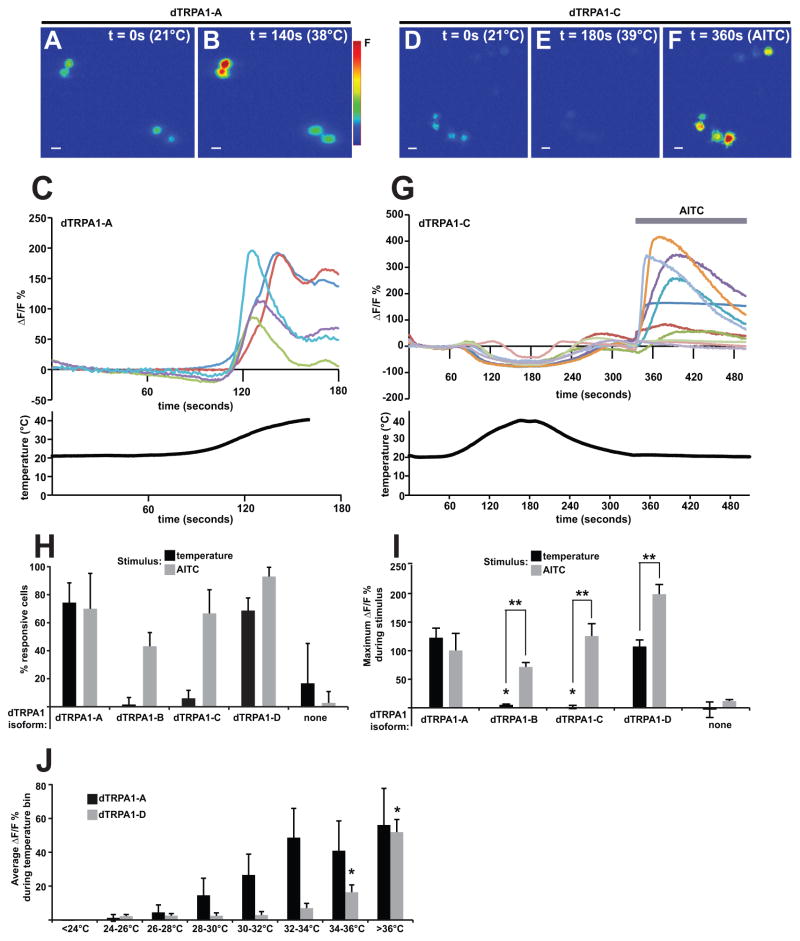

Figure 6. The dTRPA1-C isoform is not activated by temperature in heterologous expression system but does respond to allyl isothiocyanate (AITC).

Heat-induced calcium transients are observed in S2R+ cells transfected with UAS-dTrpA1-A, but not in S2R+ cells transfected with UAS-dTrpA1-C. Scale bars = 10 μm.

(A, B) Images of representative S2R+ cells transfected with dTrpA1-A and the genetically encoded calcium indicator GCaMP3.0, displaying increased GCaMP fluorescence at an elevated temperature (38°C) as compared to room temperature (21°C).

(C) Representative traces from dTrpA1-A transfected S2R+ cells showing GCaMP fluorescence (above) in response to a temperature ramp (below). Each colored trace represents an individual cell.

(D–F) Images of representative S2R+ cells transfected with UAS-dTrpA1-C and the genetically encoded calcium indicator UAS-GCaMP3.0, displaying no increase GCaMP fluorescence at an elevated temperature (39°C) as compared to room temperature (21°C), but a large increase in fluorescence in response to AITC.

(G) Representative traces from dTrpA1-A transfected S2R+ cells showing GCaMP fluorescence (above) in response to a temperature ramp (below) and application of 0.03mM AITC (gray bar). Each colored trace represents an individual cell.

(H) Percentage of S2R+ cells transfected with dTrpA1-A and GCaMP, dTrpA1-B and GCaMP, dTRPA1-C and GCaMP, dTrpA1-D and GCaMP, or GCaMP alone that displayed a peak GCaMP ΔF/F0% of greater than 50% in response to increased temperature (black bars) or 0.03mM AITC (gray bars). Cells expressing dTRPA1-A or dTRPA1-D responded to increased temperature and AITC. Cells expressing dTRPA1-B or dTRPA1-C responded to AITC, but few responded to temperature. Few GCaMP-only cells responded to increased temperature or AITC. Errors indicate 95% confidence intervals (as determined by Wilson’s estimate).

(I) Average peak ΔF/F0% of S2R+ cells transfected with dTrpA1-A and GCaMP, dTrpA1-B and GCaMP, dTRPA1-C and GCaMP, dTrpA1-D and GCaMP, or GCaMP alone in response to increased temperature (black bars) or 0.03mM AITC (gray bars). Cells expressing dTRPA1-A showed an average peak ΔF/F0% that was significantly greater than that of cells expressing dTRPA1-C or dTRPA1-B (as determined by Student’s t-test; asterisk indicates p≤ 0.001). Errors bars indicate standard errors.

(J) Average ΔF/F0% of all data points within given temperature bins for cells transfected with dTrpA1-A and GCaMP (black bars) or dTrpA1-D and GCaMP (gray bars). Cells expressing dTRPA1-D showed significantly increased GCaMP fluorescence at the 34–36°C and >36°C temperature range when compared to the 24–26°C range (as determined by one-way analysis of variance with Dunnett’s post-test; asterisk indicates p≤ 0.05). Error bars indicate standard errors.

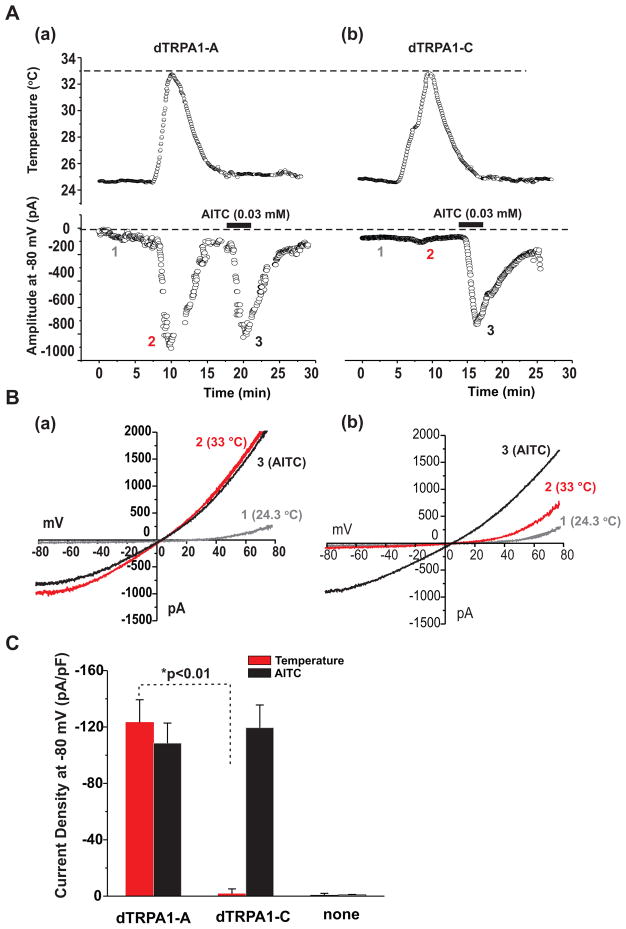

In order to further validate the heat insensitivity of the dTRPA1-C isoform revealed in Ca2+ imaging experiments, we performed whole cell patch clamp recordings on the Drosophila S2R+ cells expressing the channel. Cells were voltage-clamped at −80 mV and whole cell currents were monitored every 3 seconds with a 600 ms ramp from −80 to +80 mV. After stabilization of current at 24.3°C, the bath temperature was raised to 33°C and then returned to 24.3°C. Cells were then treated with the dTRPA1 agonist AITC. As shown in Fig. 7A–C, cells expressing dTRP1A-A showed dramatic current increases at elevated temperatures (33°C) and in response to the dTRPA1 agonist AITC. In contrast, cells expressing dTRPA1-C did not respond to temperature increases to 33°C, but did show the expected robust currents upon application of AITC. At temperatures greater than 33°C, the seal could not be maintained and this technical limitation prevented analysis of whole cell currents at the higher temperature ranges. Nevertheless, the absence of temperature responses measured in Ca2+ imaging experiments on dTRPA1-C expressing cells indicate that the channel does not show meaningful responses to temperature within the measured range of 15–42°C. Combined, these results demonstrate that the dTRPA1-C isoform has distinct thermosensory properties from the canonical, warmth-activated dTRPA1-A isoform and further suggest the possibility that dTRPA1-C is not a temperature-sensitive TRP at all.

Figure 7. Patch clamp recordings on Drosophila S2R+ show that the dTRPA1-C isoform is not activated by temperature but does respond to allyl isothiocyanate (AITC).

(A) Diary plot of current amplitude at-80 mV from a S2R+ cell transfected with dTrpA1-A (a) or dTrpA1-C (b) during a temperature challenge and after application of 0.03mM AITC. Measured temperature of the bath solution is shown in the top panels. Note the absence of a response to temperature increase for dTrpA1-C.

(B) Example current traces from a S2R+ cell transfected with dTrpA1-A (a) or dTrpA1-C (b) in response to a ramp protocol from −80 to +80 mV at 24.3°C, at 33°C, and after application of AITC at 24.3°C, taken at the indicated times (see 1, 2, and 3) in (A).

(C) Summary data showing that dTrpA1-A, but not dTrpA1-C responded to temperature. Both dTrpA1-A and dTrpA1-C responded to AITC. For current amplitude, N = 15 for dTrpA1-A and 12 dTrpA1-C. *, P<10−6; For AITC application, N = 9 and 12, respectively, P>0.05, mCD8::GFP only N=6 for temperature and N=6 for AITC application. Scale bars represent standard errors.

The surprising lack of a heat response in dTRPA1-C expressing cells and the existence of the three other dTrpA1 splice variants provided with us with an opportunity to investigate the contributions of the distinct alternatively spliced domains in heat responses. As with dTRPA1-C, we found that cells transfected with dTRPA1-B lacked Ca2+ responses to temperature in the 20–42°C temperature range (Figure 6H and 6I). Also, as with dTRPA1-C, cells expressing dTRPA1-B still showed Ca2+ responses to AITC indicating that it was an active channel (Figure 6H and 6I). In contrast, S2R+ cells transfected with the dTRPA1-D isoform showed both responses to temperature and to AITC (Figure 6H and 6I). Interestingly, cells expressing the dTRPA1-D isoform showed Ca2+ responses significantly above baseline beginning at a temperature of 34°C (Figure 6J). This temperature is significantly higher than the known temperature threshold of the dTRPA1-A isoform (27°C) but still lower than the thermal nociception threshold of 39°C. Interestingly, this 34°C Ca2+ response of dTRPA1-D transfected cells, matches the thermal allodynia threshold of larvae exposed to UV-C radiation(Babcock et al., 2009) making this isoform a good candidate for mediating allodynia responses.

These experiments reveal that the C-Terminal TAC that is shared between dTRPA1-A and dTRPA1-D, encoded by exon 12 of the locus, is essential for the heat responses of these isoforms (schematically represented in red on the protein structure of dTRPA1-D (Figure 4D)). Conversely, the equivalent domain of dTRPA1-B and C interferes with heat responses. Interestingly, the C-Terminal TAC of the heat insensitive dTRPA1-B and dTRPA1-C shows higher sequence similarity with vertebrate TRPA channels (Figure S2D) relative to the heat sensitive TAC of dTRPA1-A and dTRPA1-D. Future analyses will allow a precise investigation into which of the amino acids that vary between the C-terminal TACs are critical for temperature mediated gating of these channels.

While the molecular mechanisms of the extreme temperature sensitivity of thermoTRP channels are still largely unknown, some progress has been made. C-terminal truncations of TRPV1 change the functional properties of this channel (Vlachova et al., 2003) and swapping the C-terminus of heat-sensitive TRPV1 with cold-sensitive TRPM8 exchanges the temperature responses of the channels. Interestingly, the C terminus is not essential for TRPV1 capsaicin responsiveness or TRPM8 menthol responsiveness (Vlachova et al., 2003).

More recently, the pore region of TRPV channels has been suggested to be critical for temperature activation. Residues in the sixth transmembrane and pore region of TRPV3 are required for its heat activation (Grandl et al., 2008). Consistent with this, mutations in the outer pore region of TRPV1 also specifically impaired temperature activation (Grandl et al., 2010).

The N-terminus of the rattlesnake TRPA1 channel has been found to contain elements important for heat sensitivity(Cordero-Morales et al., 2011). Artificially constructed chimeric proteins between rattlesnake TRPA1, and human TRPA1, showed that the heat sensitive properties of the rattlesnake channel could be transferred to the heat insensitive human channel. The heat responsive elements of the rattlesnake channel appear to lie within the ankyrin repeat containing region of the protein. Importantly, two separable elements of the rattlesnake ankyrin repeat domain were found to contribute to the temperature response properties of the artificially constructed chimeric proteins. Artificial chimeric channels made between hTRPA1 and dTRPA1 suggested that amino acids 400–612 of dTRPA1-A could confer heat sensitivity to hTRPA1(Cordero-Morales et al., 2011). This region is distinct from the 37 amino acids of dTRPA1-A and dTRPA1-D that are required for heat sensitivity in the naturally occurring dTRPA1 variants. An interesting possibility, is that the c-terminal TAC domain of dTRPA1-A and dTRPA1-D interacts with ankyrin repeats in the context of the native dTRPA1 channels.

dTRPA1-A is activated by temperature range of 24–29°C while dTRPA1-B and dTRPA1-C did not respond to temperature changes within the range of 15–42°C. This indicates that critical sequences important for heat activation reside in the 37 amino acid residues that are unique to the TRPA1-A isoform. However, the N-Terminal TAC of dTRPA1-A must also contribute to temperature responses because when this segment is replaced with the N-terminal TAC of the D isoform, the threshold of the temperature response was increased to approximately 34°C.

Our results indicate that no single domain of the dTRPA1 channel can completely explain it’s thermal response properties. Complex allosteric interactions between the N-Terminal TACs and C-Terminal TAC are likely to play a role. These interactions are likely to depend on the context of intervening ankyrin repeats. Future detailed structural analyses of the four TRPA1 variants that we describe here, will allow for these mechanisms to be unraveled.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Fly strains and husbandry

The following fly strains were used: w; ppk-GAL4, w; UAS-dTrpA1-A, iso w1118; UAS-dTrpA1RNAi (VDRC GD collection transformant ID 37249), w; Df(3L)ED4415/TM6b, w; dTrpA1 W903*/TM6b, w;UAS-mCD8::GFP, UAS-dicer2, UAS-ChannelRhodopsin-2::eYFP line C (UAS-ChR2::eYFPlineC). Drosophila stocks were raised on standard cornmeal molasses fly food medium at 25°C.

Nociception assays

The thermal nociception behavioral tests were performed as described previously (Caldwell and Tracey, 2010; Hwang et al., 2007; Tracey et al., 2003; Zhong et al., 2010). The mechanical nociception behavioral tests were performed as described previously (Caldwell and Tracey, 2010; Hwang et al., 2007; Tracey et al., 2003; Zhong et al., 2010).

Gentle touch assay

The gentle touch behavioral tests were performed as described previously(Kernan et al., 1994; Zhong et al., 2010).

Confocal microscopy

For the visualization of GAL4 expression patterns via confocal microscopy dTRPA1-C-GAL4; UAS-mCD8::GFP larvae were anesthetized with ether until immobilized and mounted in glycerol. Brains of third instar larvae were dissected in PBS and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 30 minutes prior to imaging.

S2R+ cell culture and calcium imaging and electrophysiology

Drosophila S2R+ cell line was maintained in Schneider’s Drosophila medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% heat inactivated Fetal Bovine Serum. Cells grown on coverslips (Warner Instruments #1.5 Glass Coverslip 25 mm Round) in 6 well tissue culture plates (Falcon) were transfected with Ubiquitin-GAL4 (0.75 μg DNA per well), UAS-GCaMP3.0 (0.5 μg DNA per well) and either UAS-dTrpA1-A, UAS-dTrpA1-B, UAS-dTrpA1-C, or UAS-dTrpA1-D (0.25 μg DNA per well for each isoform), using Cellfectin® II Reagent (Invitrogen). For electrophysiology experiments, UAS-mCD8::GFP (0.25 μg DNA per well) was used in the transfection in place of UAS-GCamp3.0. Imaging was conducted 72 hours following the transfection. Coverslips were assembled in an imaging chamber (Warner Instrument Corporation Series 20 Chamber Platform P-2) and gently rinsed with HL3 saline (70 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 1.5 mM CaCl2, 20 mM MgCl2, 10 mM NaHCO3, 5 mM trehalose, 115 mM sucrose, and 5 mM HEPES [pH 7.2]) (Stewart et al., 1994). An inline solution heater (Warner Instrument Corporation Model SH-27B) was used to flow heated or cooled HL3 through the chamber to deliver temperature ramps. A thermocouple (Warner Instrument Corporation TA-29) was connected to a data acquisition board (Warner Instrument Corporation TC-324B) and placed in the imaging chamber to continuously monitor the bath temperature. For each heat response experiment, the bath temperature was increased from room temperature (<24°C) to 38–42°C and then cooled back to room temperature. Microscopy was performed on a Zeiss LSM 5 Live confocal system using a 20X Plan-Apochromat lens N/A 0.8 and 488 nm laser. Images were collected at 0.2–1 Hz during the temperature ramp and AITC application. The data were analyzed using the Zeiss LSM software physiology package. Individual cells were selected as regions of interest. Baseline fluorescence for each cell was calculated by determining the mean fluorescence of all time points prior to heat ramp or AITC application (>30 seconds). Peak fluorescence was determined for each cell at temperatures elevated above 24°C (for the analyses of heat responses) or following AITC application (for analyses of responses to AITC). Δ F/F0% was calculated with the formula 100% * (F-F0)/F0 where F was the fluorescence intensity at each time point and F0 was the average baseline fluorescence intensity before the introduction of any manipulation. For each imaging experiment n ≥25 transfected cells, except for the measurement of dTrpA1-A-transfected cells’ responses to AITC (n=7) and the measurement of GCaMP-only cells’ responses to temperature (n=6).

Whole cell voltage-clamp was performed on transfected S2R+ cells plated on coverslips. Transfected cells selected for recordings were identified by mCD8::GFP fluorescence. The intracellular solution contained (in mM): cesium methanesulfonic acid 135, CsCl 5, EGTA 0.5, MgCl2 1, Mg-ATP 4, HEPES 10; the was adjusted pH 7.3 with CsOH. Extracellular solution contained (in mM) NaCl 135, KCl 5, CaCl2 2, HEPES 5, Glucose 10, pH 7.3 with NaOH. Patch pipette resistance ranged from 4 to 5.5 MΩ. Recordings were obtained using EPC 10 USB patch amplifier (HEKA Instruments Inc.), and data were collected using Patchmaster (HEKA). The liquid junction potential for these recordings was not corrected, and cells were discarded if series resistance exceeded 10 MΩ. The recording were obtained at room temperature(24.3°C) except during heat stimulation, as indicated in Figure 8. The thermal stimulation was applied by increasing the recording chamber solution’s temperature with a preheated solution via an inline heater using a Temperature Controller (TC-324B, Warner Instruments Inc., Hamden, CT) and temperature was monitored with thermocouple (TA-30, Warner Instruments Inc., Hamden, CT) placed in recording chamber near the recorded cells. Data acquisition of thermistor readings outputs signal (100 mV/°C) was collected simultaneously with heat-activated currents signals. Cells were held at −80 mV and currents were monitored every 3 sec in response to a linear ramp from −80 mV to +80 mV over 600 ms. A brief 5 mV hyperpolarizing step was performed at the end of each sweep to monitor membrane resistance and asses the stability of the access resistance throughout the experiment. For statistical analysis, the currents amplitude was normalized to each cell capacitance.

Molecular cloning

For the generation of dTrpA1-GAL4, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed from a BAC clone template with the forward primer 5′-CACCCCATTCCACTTGAGTGAGGACTAC-3′ and the reverse primer 5′-GACCGCTGTAGACTCCGTTG-3′. The resulting PCR product was then cloned into pENTR/D-TOPO (Invitrogen) and then into the Drosophila pCaSpeR-DEST6 Gateway destination vector using Clonase II enzyme (Invitrogen). This construct was used for the generation of transgenic animals by the transposase-mediated transformation of w1118 flies. Expression patterns of two independent transformants were analyzed by crossing to UAS-mCD8GFP and showed similar patterns.

For the cloning of dTrpA1-C, reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) was performed from total RNA extracted from a mixed population of first and second instar Canton S larvae. Oligo (dT)12–18 (Invitrogen) and primer 5′-CTACATGCTCTTATTGAAGCTCAGGGCG-3′ mix were used as primers for reverse transcription and first-strand cDNA synthesis used SuperScriptTM II RT (Invitrogen). To amplify the cDNA, PCR was performed using the forward primer 5′-ATGCCCAAGCTCTACAACGGAGTCTA-3′ and the reverse primer:5′-CTACATGCTCTTATTGAAGCTCAGGGCG-3′. The PCR product was then re-amplified using the same pair of primers. The dTrpA1-C PCR product was cloned into TOPO-XL (Invitrogen) and fully sequenced. TOPO-XL-dTRPA1-C was further subcloned into pUAST construct using the EcoRI restriction site. For the cloning of dTrpA1-D the forward primer was 5′-CACCATGCCCAAGCTCTACAACGGAG-3′ and the reverse primer was 5′-CTACATGCTCTTATTGAAGCTCAGGG-3′. The PCR parameters were: 98 for 30 seconds>98 for 7 seconds>68 for 30 seconds>72 for 2 minutes repeat 2–4 29 times(total of 30 cycle) 72 for 8 minutes. The GENBANK accession numbers for dTrpA1-C and dTrpA1-D are JN400354 and JN814911 respectively.

To construct the pUAST-dTrpA1-B plasmid, a NheI/XbaI fragment containing the 3′ end of the dTrpA1-C cDNA and sequence encoding the C-terminal TAC region was excised from the pUAST-dTrpA1-C plasmid and ligated with T4 DNA ligase (New England Biolabs) into the a pUAST-dTrpA1-A plasmid cut with NheI/XbaI. To construct the pUAST-dTrpA1-D plasmid, a NheI/XbaI fragment containing the 3′ end of the dTrpA1-A cDNA and sequence encoding the C-terminal TAC region was excised from the pUAST-dTrpA1-A plasmid and ligated with T4 DNA ligase (New England Biolabs) into the a pUAST-dTrpA1-C plasmid cut with NheI/XbaI.

Transgenic flies

The pCaSpeR-DEST6-dTrpA1-GAL4 construct was injected by the Duke Transgenic fly facility for P-element mediated transformation. This particular line used in this research is an insertion on the second chromosome. Injections for dTrpA1BAC (CH322-154N09) were performed by Genetivision via PhiC31 mediated chromosome integration with VK37(2L)22A3 as the docking site (Venken et al., 2006). The pUAST-dTRPA1-C construct was injected by Genetivision for P-element mediated transformation.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Two isoforms of dTRPA1 are heat sensors and two are not.

The dTRPA1-C isoform of dTRPA1 shows specific expression in nociceptors.

dTRPA1-C is not a thermoTRP but it is required for thermal nociception.

37 amino acids encoded by exon 12 are essential for thermal activation.

Acknowledgments

We thank Paul Garrity for the UAS-dTRPA1-A strains and UAS-dTRPA1-A cDNA clone. We also thank the Bloomington Drosophila stock center for supplying other strains used in this study. Asako Tsubouchi, Jason Caldwell, Stephanie Mauthner and Kia Walcott made helpful suggestions on the manuscript. This work was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Neurological Disorders and Stroke 5R01NS054899 to WDT, KH is a fellow of the Ruth K. Broad Biomedical Research Foundation, AB is a fellow supported by a National Institute of General Medicine Postdoctoral Training Grant 5T32GM008600, JR is supported by a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship and a James B. Duke Fellowship.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Babcock DT, Landry C, Galko MJ. Cytokine signaling mediates UV-induced nociceptive sensitization in Drosophila larvae. Curr Biol. 2009;19:799–806. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.03.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babcock DT, Shi S, Jo J, Shaw M, Gutstein HB, Galko MJ. Hedgehog Signaling Regulates Nociceptive Sensitization. Curr Biol. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bautista DM, Jordt SE, Nikai T, Tsuruda PR, Read AJ, Poblete J, Yamoah EN, Basbaum AI, Julius D. TRPA1 mediates the inflammatory actions of environmental irritants and proalgesic agents. Cell. 2006;124:1269–1282. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bautista DM, Movahed P, Hinman A, Axelsson HE, Sterner O, Hogestatt ED, Julius D, Jordt SE, Zygmunt PM. Pungent products from garlic activate the sensory ion channel TRPA1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:12248–12252. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505356102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brierley SM, Castro J, Harrington AM, Hughes PA, Page AJ, Rychkov GY, Blackshaw LA. TRPA1 contributes to specific mechanically activated currents and sensory neuron mechanical hypersensitivity. J Physiol. 2011;589:3575–3593. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.206789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell JC, Tracey WD., Jr Alternatives to mammalian pain models 2: using Drosophila to identify novel genes involved in nociception. Methods Mol Biol. 2010;617:19–29. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60327-323-7_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caterina MJ, Leffler A, Malmberg AB, Martin WJ, Trafton J, Petersen-Zeitz KR, Koltzenburg M, Basbaum AI, Julius D. Impaired nociception and pain sensation in mice lacking the capsaicin receptor. Science. 2000;288:306–313. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5464.306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper JL, Till BJ, Henikoff S. Fly-TILL: reverse genetics using a living point mutation resource. Fly (Austin) 2008;2:300–302. doi: 10.4161/fly.7366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordero-Morales JF, Gracheva EO, Julius D. Cytoplasmic ankyrin repeats of transient receptor potential A1 (TRPA1) dictate sensitivity to thermal and chemical stimuli. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1114124108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grandl J, Hu H, Bandell M, Bursulaya B, Schmidt M, Petrus M, Patapoutian A. Pore region of TRPV3 ion channel is specifically required for heat activation. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11:1007–1013. doi: 10.1038/nn.2169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grandl J, Kim SE, Uzzell V, Bursulaya B, Petrus M, Bandell M, Patapoutian A. Temperature-induced opening of TRPV1 ion channel is stabilized by the pore domain. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:708–714. doi: 10.1038/nn.2552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamada FN, Rosenzweig M, Kang K, Pulver SR, Ghezzi A, Jegla TJ, Garrity PA. An internal thermal sensor controlling temperature preference in Drosophila. Nature. 2008;454:217–220. doi: 10.1038/nature07001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang RY, Zhong L, Xu Y, Johnson T, Zhang F, Deisseroth K, Tracey WD. Nociceptive neurons protect Drosophila larvae from parasitoid wasps. Curr Biol. 2007;17:2105–2116. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.11.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordt SE, Bautista DM, Chuang HH, McKemy DD, Zygmunt PM, Hogestatt ED, Meng ID, Julius D. Mustard oils and cannabinoids excite sensory nerve fibres through the TRP channel ANKTM1. Nature. 2004;427:260–265. doi: 10.1038/nature02282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kernan M, Cowan D, Zuker C. Genetic dissection of mechanosensory transduction: mechanoreception-defective mutations of Drosophila. Neuron. 1994;12:1195–1206. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90437-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kremeyer B, Lopera F, Cox JJ, Momin A, Rugiero F, Marsh S, Woods CG, Jones NG, Paterson KJ, Fricker FR, et al. A gain-of-function mutation in TRPA1 causes familial episodic pain syndrome. Neuron. 2010;66:671–680. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.04.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwan KY, Allchorne AJ, Vollrath MA, Christensen AP, Zhang DS, Woolf CJ, Corey DP. TRPA1 contributes to cold, mechanical, and chemical nociception but is not essential for hair-cell transduction. Neuron. 2006;50:277–289. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.03.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon Y, Kim SH, Ronderos DS, Lee Y, Akitake B, Woodward OM, Guggino WB, Smith DP, Montell C. Drosophila TRPA1 channel is required to avoid the naturally occurring insect repellent citronellal. Curr Biol. 2010;20:1672–1678. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macpherson LJ, Dubin AE, Evans MJ, Marr F, Schultz PG, Cravatt BF, Patapoutian A. Noxious compounds activate TRPA1 ion channels through covalent modification of cysteines. Nature. 2007;445:541–545. doi: 10.1038/nature05544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neely GG, Keene AC, Duchek P, Chang EC, Wang QP, Aksoy YA, Rosenzweig M, Costigan M, Woolf CJ, Garrity PA, et al. TrpA1 Regulates Thermal Nociception in Drosophila. PLoS One. 2011;6:e24343. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenzweig M, Brennan KM, Tayler TD, Phelps PO, Patapoutian A, Garrity PA. The Drosophila ortholog of vertebrate TRPA1 regulates thermotaxis. Genes Dev. 2005;19:419–424. doi: 10.1101/gad.1278205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart BA, Atwood HL, Renger JJ, Wang J, Wu CF. Improved stability of Drosophila larval neuromuscular preparations in haemolymph-like physiological solutions. J Comp Physiol A. 1994;175:179–191. doi: 10.1007/BF00215114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Story GM, Peier AM, Reeve AJ, Eid SR, Mosbacher J, Hricik TR, Earley TJ, Hergarden AC, Andersson DA, Hwang SW, et al. ANKTM1, a TRP-like channel expressed in nociceptive neurons, is activated by cold temperatures. Cell. 2003;112:819–829. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00158-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian L, Hires SA, Mao T, Huber D, Chiappe ME, Chalasani SH, Petreanu L, Akerboom J, McKinney SA, Schreiter ER, et al. Imaging neural activity in worms, flies and mice with improved GCaMP calcium indicators. Nat Methods. 2009;6:875–881. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tracey WD, Wilson RL, Laurent G, Benzer S. painless, a Drosophila Gene Essential for Nociception. Cell. 2003;113:261–273. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00272-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venken KJ, He Y, Hoskins RA, Bellen HJ. P[acman]: a BAC transgenic platform for targeted insertion of large DNA fragments in D. melanogaster. Science. 2006;314:1747–1751. doi: 10.1126/science.1134426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viswanath V, Story GM, Peier AM, Petrus MJ, Lee VM, Hwang SW, Patapoutian A, Jegla T. Opposite thermosensor in fruitfly and mouse. Nature. 2003;423:822–823. doi: 10.1038/423822a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vlachova V, Teisinger J, Susankova K, Lyfenko A, Ettrich R, Vyklicky L. Functional role of C-terminal cytoplasmic tail of rat vanilloid receptor 1. J Neurosci. 2003;23:1340–1350. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-04-01340.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waxman SG. Channelopathic pain: a growing but still small list of model disorders. Neuron. 2010;66:622–624. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler JC, VanderZwan C, Xu X, Swantek D, Tracey WD, Gergen JP. Distinct in vivo requirements for establishment versus maintenance of transcriptional repression. Nat Genet. 2002;32:206–210. doi: 10.1038/ng942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiang Y, Yuan Q, Vogt N, Looger LL, Jan LY, Jan YN. Light-avoidance-mediating photoreceptors tile the Drosophila larval body wall. Nature. 2010 doi: 10.1038/nature09576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanagawa S, Lee JS, Ishimoto A. Identification and characterization of a novel line of Drosophila Schneider S2 cells that respond to wingless signaling. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:32353–32359. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.48.32353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong L, Hwang RY, Tracey WD. Pickpocket is a DEG/ENaC protein required for mechanical nociception in Drosophila larvae. Curr Biol. 2010;20:429–434. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.12.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.