Abstract

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a multifactorial condition with principal symptoms of pain and altered bowel function. The kappa-opioid agonist asimadoline is being evaluated in Phase III as a potential treatment for IBS. Asimadoline, to date, has shown a good safety profile and the target Phase III population – diarrhea-predominant IBS patients with at least moderate pain – was iteratively determined in a prospective manner from a Phase II dose-ranging study. The clinical data in support of this population are reviewed in this article. Furthermore, the scientific rationale for the use of asimadoline in the treatment of IBS is reviewed. Considering the high patient and societal burdens of IBS, new treatments for IBS represent therapeutic advances.

Keywords: irritable bowel syndrome, kappa-opioid agonist, asimadoline, visceral pain, visceral hypersensitivity

Introduction

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) remains one of the most common disorders seen by gastroenterologists.1–3 Although IBS itself does not lead to a more sinister pathology, the magnitude and importance of the symptoms associated with IBS result in patients undergoing more surgical procedures in search of other etiologies to explain and treat their symptoms, reduced quality of life, increased health care expenditures, increased work absenteeism, reduced productivity while at work, and increased psychological disorders.3–11 Thus, the burden of IBS on the patient and in terms of societal costs is large. Considering this, finding new, safe, and efficacious treatments for IBS is of large importance both at the patient level and also to reduce the overall burden on the health care system.

IBS has been estimated to have a prevalence of approximately 6%–12% in Western countries.9,12–14 Most studies show IBS to be a disorder predominantly in females, with a female-to-male ratio of 2–2.5 to 1. In many patients, symptoms begin in childhood or young adulthood, and often continue throughout their lives with an episodic course of exacerbations and remissions.

The principal symptoms of IBS are abdominal pain and altered bowel function.15 The alterations in bowel function may manifest as diarrhea, constipation, or an alternation between the two bowel states. These abnormal bowel patterns have led to subtyping of IBS as diarrhea-predominant IBS (D-IBS), constipation-predominant IBS (C-IBS), and mixed or alternating IBS (A-IBS).15 As discussed later in this review, the abdominal pain associated with IBS is a consequence of a state of heightened visceral nociception.15

Effective treatments for IBS need to improve both abdominal pain and abnormal bowel patterns. To date, few contemporary agents have obtained regulatory approval for the treatment of IBS. In considering a reasonable profile for future IBS treatments, several features should be noted. First, there should not be the expectation that a single agent will be efficacious in more than one subtype of IBS. Present-day agents have been shown to be efficacious in only one IBS subtype, reflecting that improvement by the same agent for states of both diarrhea and constipation is unlikely. This presents challenges for the treatment of the A-IBS population. Some have proposed to study A-IBS patients in either their diarrhea or their constipated states, and then combine those populations with either D-IBS or C-IBS patients for indications of nonconstipated IBS patients or constipated IBS patients, respectively. We believe that to achieve these indications, it would be most appropriate to have completed long-term safety information both in D-IBS or C-IBS patients and in an all-comer population of A-IBS patients. A-IBS patients in their diarrheal phase will eventually alternate from their state of diarrhea to constipation; therefore, an all-comer A-IBS population should be used in safety studies. Second, effective IBS treatments must treat abdominal pain. Agents that treat only abnormal bowel function in IBS patients may be classified as laxatives or antidiarrheals, but are not IBS treatments just because they treat abnormal bowel function in IBS patients. Third, in evaluating datasets from randomized, placebo-controlled IBS studies, relevant subgroups should be considered. For all datasets in IBS patients, analyses should be conducted on patients stratified by gender and IBS subtype. Depending on the specific agent, other prespecified analyses may include efficacy by baseline pain. Finally, duration of action ideally should persist as long as treatment does. Some agents show a dissipation of effect with continued treatment. However, this latter point has not been and is not an absolute barrier to drug approval.

When evaluating currently available therapeutic options for the treatment of IBS, few drugs have regulatory approval. For D-IBS patients, alosetron remains the gold standard therapy with respect to drug efficacy. Alosetron shows excellent efficacy in the treatment of multiple symptoms of IBS in diarrhea-predominant patients.16,17 Most notably, improvement is seen on adequate relief of IBS pain and discomfort, urgency, stool consistency, and stool frequency. However, the potential use of alosetron will always be limited by its safety profile. With alosetron, significant constipation occurred in approximately 25% of the patients enrolled in clinical trials.17 Constipation was responsible for the withdrawal of approximately 10% of patients from clinical trials,17 and ischemic colitis was also reported in association with the use of alosetron.

The only other agent for which regulatory approval for D-IBS has been sought in contemporary time is rifaximin. Rifaximin shows marginal efficacy, with differences of rifaximin over placebo in the two pivotal studies of approximately 9% on the primary endpoint.18,19 Evaluation of abdominal pain also showed benefit of less than a 10% difference with rifaximin as compared with placebo. For several endpoints, efficacy with rifaximin dissipated over time in the 10-week observation period following 2 weeks of dosing. The initial new drug application (NDA) for rifaximin in the treatment of IBS was rejected due to lack of long-term safety or repeat-use data.

At the time of the writing of this manuscript, the kappa-opioid agonist asimadoline is in Phase III development for the treatment of D-IBS patients. The available data on asimadoline as a potential treatment for IBS are reviewed in this manuscript.

For the treatment of C-IBS, tegaserod showed benefit on multiple symptoms in C-IBS patients,20,21 but tegaserod was ultimately withdrawn from marketing because of cardiovascular safety concerns. Lubiprostone is indicated for the treatment of patients with C-IBS. Efficacy with lubiprostone is not robust, with differences on the primary endpoint as compared with placebo of 7.8% (17.9% vs 10.1%).22 Evaluation of data during the individual months of treatment showed significance in one Phase III study only at month 2, and in the other study at months 2 and 3. Magnitudes of improvement in pain were not clinically relevant.

Based on the publicly available data, we believe that linaclotide for the treatment of C-IBS will achieve regulatory approval. Linaclotide shows statistically significant benefit on multiple endpoints including bowel movement frequency, pain, straining, bloating, and stool consistency.23

Asimadoline: a peripherally restricted kappa-opioid receptor agonist

For a putative opioid agonist or antagonist, the importance of selectivity across opioid class receptors should not be underestimated. The effects and side effects of centrally active analgesic mu-opioid receptor agonists, such as euphoria, respiratory depression, tolerance, dependence, and withdrawal, can be significant, especially if agents are used as chronic treatments. Peripherally restricted mu-opioid receptor agonists (eg, loperamide) are powerful antidiarrheal agents but do not show convincing analgesic activity.24 The kappa-opioid receptor agonist asimadoline, by contrast, produces both analgesic and antidiarrheal effects presumably via an action in the periphery. Activity in the central nervous system (CNS) is not necessary for efficacy of asimadoline in the treatment of IBS. When kappa-opioid agonists penetrate the CNS at sufficient levels, they do not produce the mu-like opioid side effects of respiratory depression or euphoria; however, kappa receptor activation in the CNS results in other undesirable adverse effects such as dysphoria, sedation, and diuresis.25 In the study of IBS, low levels of asimadoline are used such that these side effects do not occur.

Receptor binding and functional assays performed with asimadoline reveal it to be a potent, full agonist at kappa-opioid receptors.26 A half-maximum inhibitory concentration (IC50) of 1.2 nM (Ki, 0.6 nM) was determined in radioligand binding assays using human recombinant kappa-opioid receptors expressed in CHO cells. Studies in preclinical species revealed a similar high-affinity binding of asimadoline at guinea pig brain kappa receptors (IC50, 3–6 nM). Asimadoline is a potent, full agonist at kappa-opioid receptors in functional assays using rabbit vas deferens and guinea pig ileum.

Asimadoline is highly selective for kappa-opioid receptors, having approximately 400- to 500-fold lower affinity for recombinant human mu-opioid (IC50, 601 nM; Ki, 216 nM) or delta-opioid (IC50, 597 nM; Ki, 313 nM) receptors expressed in CHO cells.26 Studies in preclinical species revealed a similar high degree of selectivity for kappa receptors. Asimadoline is also highly specific, demonstrating no affinity below the micromolar range for any other receptor tested. Although arylacetamide kappa-opioid receptor agonists have been shown to block sodium channels at high concentrations,27 asimadoline is 500- to 1000-fold less potent in this activity than it is as a kappa-opioid receptor agonist,28 which makes it highly unlikely that this activity has any relevance to the clinical effect of the drug at the IBS dose.

Following oral administration to rats, dogs, or monkeys, asimadoline is rapidly absorbed with a time to maximum plasma concentrations (Tmax) of 0.25 to 1 hour and an absolute oral bioavailability of 6%–20%.26,29 The drug is distributed with a half-life of 2–3 hours and has a terminal elimination half-life of 15–20 hours; steady state for twice-daily (bid) treatment occurs after 2–3 days (Tioga Pharmaceuticals, Inc, unpublished data). In humans following oral administration of single doses of 0.15–15 mg, bioavailability is approximately 50%; maximum plasma concentrations (Cmax) are seen after 0.8–1.4 hours, and both Cmax and area under the curve (AUC) increased in a dose-proportional manner (Tioga Pharmaceuticals, Inc, unpublished data).30

Preclinical studies26,29 demonstrate that the distribution of asimadoline into tissues and organs is rapid, with concentrations several-fold higher than plasma in the liver, kidney, and lung. In contrast, less than 1% of total tissue concentration was found in the brain 1 hour following either single intravenous or oral doses.29 This very limited penetration of asimadoline into the CNS is in part due to its amphiphilic chemical structure, which limits its penetration across the blood-brain barrier, and in part because it is a substrate for P-glycoprotein (P-gp).26,29 Importantly, studies performed in nonclinical species31 and in man (Tioga Pharmaceuticals, Inc, unpublished data) have shown only minor increases in asimadoline exposure in the presence of powerful P-gp inhibitors; therefore, the risk from drug-drug interactions with drugs that are P-gp inhibitors is considered negligible.

Clinical pharmacodynamic studies in healthy volunteers provide further strong evidence for the limited CNS penetration of asimadoline. Diuresis is a class effect of kappa agonists in animals and humans mediated via actions both within the blood-brain barrier at the hypothalamic-neurohypophyseal nerve terminal to inhibit release of antidiuretic hormone (ADH) and via a direct action in the kidney.32–35 In a placebo-controlled crossover study36 of the effect of asimadoline on renal function in healthy volunteers, 5 mg and 10 mg single doses of asimadoline led to an increase in free water excretion (150–200 mL over the 4-hour collection period post dose) without effect on urinary electrolytes. There was no concomitant inhibition of plasma ADH, suggesting that this aquaretic effect was not mediated centrally. However, under stimulated conditions of osmotic challenge, an inhibition of the enhanced plasma ADH was observed at the 10 mg dose, suggesting CNS activity of asimadoline at the 10 mg dose, 20-fold higher than the IBS dose.

A drug interaction study investigating the coadministration of asimadoline with the P-gp and CYP3A4 inhibitor ketoconazole was performed in healthy volunteers (Tioga Pharmaceuticals, Inc, unpublished data). Single (1.5 mg) and multiple (1.5 mg bid for 6 days) doses of asimadoline were administered in the presence of steady-state ketoconazole (200 mg bid for duration of a 10-day study). Assessment of potential CNS-mediated effects of asimadoline was made using several pharmacodynamic endpoints. A modest, two-to three-fold increase in AUC and Cmax of asimadoline was observed with concomitant administration of ketoconazole. However, even in the presence of this enhanced exposure, equivalent to eight times the Cmax reached during 0.5 mg bid dosing (the target IBS dose), there were no effects upon any of the measured CNS endpoints. It was concluded that the threshold for CNS effects of asimadoline is at least ten-fold higher than drug levels achieved in the IBS setting, in good agreement with the experience from clinical safety and efficacy studies performed to date.

Visceral analgesic and antihyperalgesic actions

Kappa-opioid receptors are members of the superfamily of inhibitory GTP-binding regulatory protein (G protein)- coupled receptors, which activate potassium channels, inhibit calcium channels, and inhibit adenylate cyclase activity, all resulting in an inhibition of neuronal excitability.37–39 Kappa-opioid receptors are thought to be located on the terminals of a variety of neurons, including those extrinsic visceral afferent neurons that transmit sensory signals from the gut to the CNS.40–45 A broad literature46 describes a peripherally mediated, visceral analgesic and antihyperalgesic activity of kappa-opioid receptor agonists.

The fundamental mechanism of action for production of the visceral analgesic effect of kappa-opioid receptor agonists is an inhibition of the excitability of visceral afferent nerve terminals in the gut wall, causing a reduction of action potential firing and neurotransmitter release from those sensory nerves.46 An action in the CNS does not appear to be necessary for visceral analgesia with kappa-opioid receptor agonists.41–43 However, the presence of visceral hypersensitivity is thought to be important for optimum visceral analgesic effect of kappa-opioid receptor agonists.45,47,48 The analgesic potency of asimadoline is increased in visceral pain models in the presence of visceral hypersensitivity.47,48 Previous studies in somatic pain models demonstrated that the potency of asimadoline’s analgesic effect is higher following the induction of hyperalgesia.26 Such antihyperalgesic effects may be produced by asimadoline’s abilities to reduce expression of substance P and calcitonin gene-related peptide in dorsal root ganglia (DRG) neurons in chronic hyperalgesia and to inhibit plasma extravasation and the release of neurogenic inflammatory mediators.26,49,50

Recently, data from studies of peripheral sensory nerves (trigeminal ganglion) in rats suggest that peripheral kappa-opioid receptors require stimuli associated with sensitization processes to become functional.51 Such induction of “ functional competence” of kappa-opioid receptors by sensitizing agents (eg, bradykinin) involves the phospholipase C pathway, arachidonic acid metabolism, and membrane integrins. Earlier work described kappa-opioid receptors in peripheral sensory nerves as dormant “silent” receptors, showing that neuronal depolarization stimulates kappa-opioid receptor mRNA expression, axonal transport, and protein translation in DRG neurons.52–55 The authors described a membrane depolarization-induced de novo synthesis of kappa-opioid receptors in DRG that was mediated by a netrin-1-induced translocation of mRNA to the transcriptionally active polyribosomal fraction. The effect was dependent on calcium influx via L-type calcium channels, and Copb1-dependent trafficking of mRNA along axons was also demonstrated. Such neuronal activity-dependent and/or sensitization-dependent increases in kappa-opioid receptor expression and function may underlie the preferential efficacy of asimadoline in hypersensitive states both in animal models and in man.

Pharmacodynamic studies with asimadoline also suggest a preferential efficacy against visceral pain in patients with visceral hypersensitivity. Delvaux et al45 evaluated asimadoline for potential analgesic activity in IBS patients with significant pain symptoms and demonstrated visceral hypersensitivity (pain threshold ≤32 mmHg). The crossover study design compared the effect of single doses of placebo with 0.5 mg asimadoline upon distensions over a range of pressures up to 45 mmHg. Asimadoline produced a significant reduction of the AUC of pain intensity (rated at each distension step) and a small but nonsignificant increase in pain threshold, compared with placebo. No effect on colonic compliance or perception of nonpainful distensions was observed. Delgado-Aros et al56 performed similar barostat studies in healthy volunteers. The parallel-group study compared single doses of placebo with 0.15 mg, 0.5 mg, and 1.5 mg asimadoline. Colonic distensions at 8 mmHg, 16 mmHg, 24 mmHg, and 32 mmHg were rated for gas and pain perception scores using a 100 mm visual analogue scale (VAS). Although pain scores were lower in the 0.5 mg dose group at all distension levels, the differences were not statistically significant, including at the two higher pressure distension levels, which elicited pain scores of 40–50 mm on the VAS, suggesting that kappa receptor activation does not significantly inhibit moderate to high-level noxious sensations in health. Asimadoline at 0.5 mg and 1.5 mg had mixed inhibitory or excitatory effects on low-threshold gas and pain sensations in response to low pressure (8 mmHg and 16 mmHg) distension, which were scored below 35 mm on the VAS. This suggests a potential role for kappa receptors in modulation of less noxious sensations in the “nonsensitized” state of health. The findings from these two studies correlate with the clinical experience gained to date from efficacy and safety studies with asimadoline, in which efficacy against symptoms of IBS is greatest in patients with a higher symptom burden.57

Antidiarrheal actions

Kappa receptors are found on cholinergic terminals of enteric neurons of the myenteric plexus where they inhibit cholinergic transmission and inhibit propulsive motility when studied in vitro.58,59 However, there is a paucity of data concerning any role of kappa-opioid receptors in gastrointestinal secretion. Immunohistochemistry studies in gastrointestinal tissues from pig,60 rat,61 and guinea pig62 demonstrate a preferential distribution of kappa-opioid receptors in the myenteric plexus, with either low or no immunoreactivity found in submucous plexus neurons where mu-opioid receptors predominate. However, in mice the opposite distribution has been described for kappa-opioid receptors, along with an up-regulation of these receptors in the submucous plexus during inflammation.63 Asimadoline has no effect on normal gastrointestinal transit in the small intestine in mice26 or on colonic transit or postprandial motility in healthy normal volunteers,56 but inhibits stress-induced fecal output in rats (Tioga Pharmaceuticals, Inc, unpublished data) and reduces diarrhea in D-IBS patients without producing constipation.57 Thus, although kappa-opioid receptors are found in the ENS, they do not appear to be critical mediators of normal motility and secretory processes in the normal state. The lack of a constipating effect of kappa receptor agonists in D-IBS may be due to their preferential localization in the myenteric plexus such that secretory processes are not inhibited; in addition, their presynaptic localization may allow for a more subtle modulation of motility in contrast to the stronger inhibitory influence on both motility and secretion produced by the broader localization of mu-opioid receptors both presynaptically and on cell bodies of both myenteric and submucosal plexus neurons.60–62 In addition, a similar reliance upon a hypersensitizing stimulus for receptor functionality, as described above for peripheral sensory nerves, may exist in the ENS, especially in the submucous plexus.63

It is also possible that the effect of asimadoline on sensitized gastrointestinal transit may also be mediated by a non-ENS site of action. Several studies have demonstrated altered postprandial motility and symptoms in functional bowel disorder patients. Of note in D-IBS patients are increased small bowel motility,64 faster orocecal transit,65 faster ileocolonic transit,66 increased colonic motility index, greater number of high amplitude propagating contractions and shortened colonic transit time,67 and increase in meal-related or postprandial symptoms.68 Such enhanced “gastrocolic” responses may be the result of hypersensitivity in the extrinsic vagal and or spinal nerves that mediate these reflexes, and inhibition of these enhanced reflexes is an interesting potential mechanism of action for asimadoline in the reduction of diarrhea and other symptoms in these patients.

Clinical trials with asimadoline in the treatment of IBS

Based on the results of the barostat study in IBS patients,45 a randomized, multicenter, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging IBS trial was conducted with asimadoline.59,69 This Phase IIb trial enrolled approximately 600 patients, including patients with all three IBS subtypes, as well as male and female IBS patients. Prospectively defined subgroup analyses were done by degree of baseline pain, as well as by gender and IBS subtype.

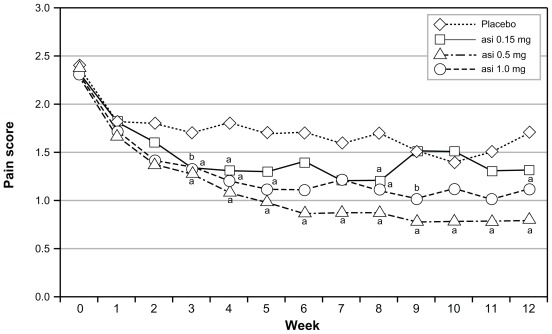

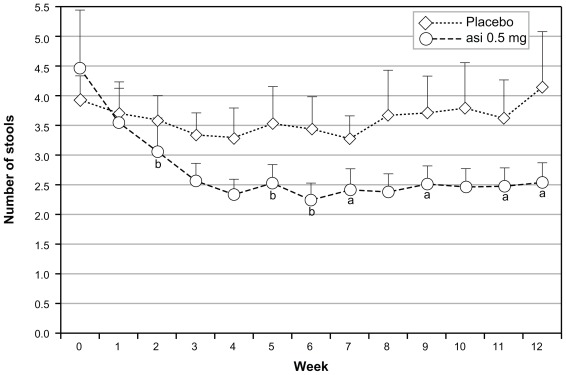

In the intent-to-treat population, asimadoline at doses of 0.15 mg, 0.5 mg, or 1.0 mg was given bid and no dose level distinguished itself from placebo (bid). Following the prospectively planned analysis scheme, numerically and statistically significant benefit was seen with all doses of asimadoline in patients with higher levels of baseline pain.57,69 One-third of the patients who entered the trial with the highest level of baseline pain showed excellent benefit on multiple endpoints. Similar benefit was seen in both genders, but efficacy was driven by D-IBS patients. Thus, the Phase IIb study identified a target population for progression into Phase III of male and female D-IBS patients who had more severe pain at baseline. For ease of recruitment into the Phase III program, the target population became D-IBS patients with at least moderate pain at baseline. Analyses of this population from the Phase IIb data yielded excellent efficacy results on pain scores (Figure 1), stool frequency (Figure 2), pain-free days, urgency, bloating, and adequate relief.57

Figure 1.

Effects of asimadoline on pain scores in D-IBS patients with at least moderate pain at baseline: asimadoline (asi) and placebo were administered twice daily for up to 12 weeks. Pain scores were collected daily and averaged numerically on a weekly basis. Week 0 represents the 2-week baseline period. As is apparent, with 0.5 mg and 1.0 mg dose levels, a substantial reduction in pain occurred, compared with placebo. Copyright © 2008. Reproduced with permission from Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. Mangel AW, Bornstein JD, Hamm LR, et al. Clinical trial: asimadoline in the treatment of patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;28(2):239–249.

Note: aP < 0.05; bP < 0.10.

Abbreviation: D-IBS, diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome.

Figure 2.

Effects of asimadoline (asi) on stool frequency in D-IBS patients with at least moderate pain at baseline: asimadoline (0.5 mg) and placebo were administered twice daily for up to 12 weeks. Stool frequency was collected daily and averaged numerically on a weekly basis. Week 0 represents the 2-week baseline period. As is apparent, with the 0.5 mg dose level a substantial reduction in stool frequency occurred, compared with placebo.

Notes: Bars represent standard errors. Data provided by Tioga Pharmaceuticals, San Diego, CA. aP < 0.05; bP < 0.10.

Abbreviation: D-IBS, diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome.

By contrast to the above study, a single-center study that analyzed data on the basis of on-demand or as-needed use did not show efficacy of asimadoline.70 The reason for the lack of efficacy is unclear.

Asimadoline has an extensive safety database.69,71 More than 1000 humans have been exposed to asimadoline in clinical trials. Single doses of asimadoline as high as 15 mg and repeat doses up to 10 mg administered daily for up to 8 weeks have been evaluated in various Phase I and Phase II studies. With the dosage level being evaluated in the Phase III asimadoline program, 0.5 mg bid, a very good safety profile has been observed (Table 1). Significantly, for a drug intended to treat D-IBS patients, no increase in constipation was reported. The most common adverse events seen in the Phase IIb IBS trial are shown in Table 2 for the efficacy population being evaluated in Phase III. Constipation is once again included, as it is a significant adverse event to consider in D-IBS patients. No safety signals were observed.

Table 1.

Most common adverse events seen in nonirritable bowel syndrome asimadoline trials

| Adverse event | Percentage of patients with adverse event | |

|---|---|---|

| Placebo (n = 224) | Asimadoline (0.15–2.0 mg/day) (n = 171) | |

| Headache | 8% | 5% |

| Thirst | 7% | 5% |

| Nausea | 4% | 4% |

| Dizziness | 4% | 3% |

| Polyuria | 2% | 1% |

| Diarrhea | 4% | 2% |

| Fatigue | 2% | 1% |

| Vomiting | 1% | 1% |

| Constipation* | 0% | 0% |

Note: Although no cases of constipation were reported, this is listed due to the importance of constipation in a D-IBS population. Data provided by Tioga Pharmaceuticals, San Diego, CA.

Abbreviation: D-IBS, diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome.

Table 2.

Most common adverse events in Phase IIb irritable bowel syndrome asimadoline trial among D-IBS patients with at least moderate pain at baseline

| Adverse events | Number of patients with adverse event (Asimadoline dose, twice daily) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo (n = 30) | 0.15 mg (n = 25) | 0.5 mg (n = 23) | 1.0 mg (n = 26) | |

| Diarrhea | 2 | 6 | 3 | 3 |

| Sinusitis | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| Nausea | 0 | 1 | 4 | 0 |

| Abdominal pain | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Headache | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Dry mouth | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Constipation | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Dizziness | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Fatigue | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

Note: Data provided by Tioga Pharmaceuticals, San Diego, CA.

Abbreviation: D-IBS, diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome.

Conclusion

Treatment of patients with IBS remains a perplexing problem. Several confounding factors contribute to the difficulties in developing therapeutics. IBS is a multifactorial condition with principal symptoms of pain and altered bowel function. Pain is always a difficult symptom to treat. Furthermore, IBS is subtyped into three principal groups, and the likely scenario is that the same medication will not work for more than one subtype of patients because of the difference in the type of bowel dysfunction. Additionally, although there are pharmacodynamic models by which to study transit and pain, there is no true animal model of IBS against which candidate therapeutics can be tested.

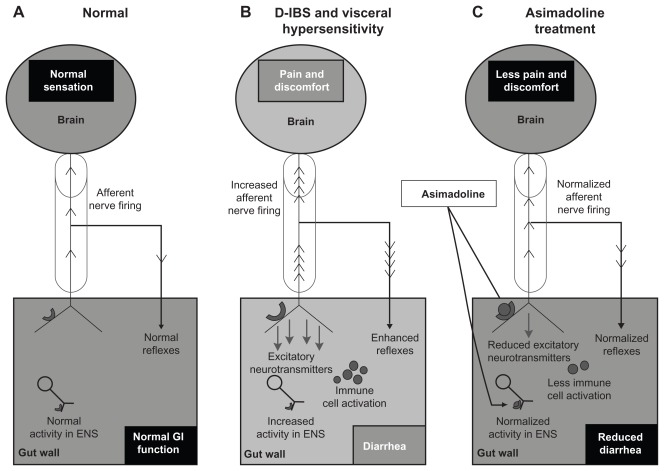

The kappa-opioid agonist asimadoline represents a potential treatment for IBS. Asimadoline, to date, has a good safety profile, and the target population showing strong efficacy was iteratively dissected from the Phase IIb data to optimize the likelihood of success in Phase III. There is a sound scientific basis for use of asimadoline in the treatment of IBS. Although an action of asimadoline in the ENS cannot be excluded, one potential mechanism of action that may explain all of the effects of asimadoline (on sensory and bowel function symptoms) in IBS is the activation of up-regulated kappa-opioid receptors on hypersensitive extrinsic afferent nerve terminals in the gut wall (Figure 3). This may result in (1) reduced sensory output from the gut to the spinal cord and brain, thereby directly inhibiting sensory symptoms and reducing augmented local motility reflexes that may contribute to sensory symptoms and diarrhea, and (2) reduced neurotransmitter release in the gut wall, which may lead to reduced diarrhea and potentially to a reduced level of peripheral, and subsequently central, sensitization in the brain–gut axis.

Figure 3.

Proposed mechanism of action of asimadoline in the treatment of D-IBS. (A) The “brain–gut” axis in the normal state (health). Sensory information is conveyed to the brain via the spinal cord (cylinder) by extrinsic VAN. Local reflexes and descending regulatory input from the CNS via autonomic efferent nerves (not shown) control overall gut function. Normal secretomotor function is coordinated by the ENS. (B) Visceral hypersensitivity in D-IBS drives increased activity in VAN resulting in increased sensory signaling to the brain and enhanced local reflexes, contributing to diarrhea. The accompanying transmitter release into the gut wall results in increased ENS activity (leading to diarrhea) and immune cell activation, which heightens sensitization. Kappa receptor expression on VAN terminals is up-regulated due to sensitization. (C) Asimadoline activates kappa-opioid receptors on VAN, leading to reduced sensory input to the brain, reduced local reflexes, and reduced transmitter release. Asimadoline also acts presynaptically to reduce neurotransmitter release in the ENS. Pain, diarrhea, and visceral hypersensitivity are reduced.

Abbreviations: CNS, central nervous system; D-IBS, diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome; ENS, enteric nervous system; VAN, visceral afferent nerves.

Footnotes

Disclosure

During the past year, A Mangel has participated in projects for the following sponsors: C-Path Institute, Tucson, AZ; Tioga Pharmaceuticals, San Diego, CA; Theravance, South San Francisco, CA; Novartis International AG, Basel, Switzerland; GlaxoSmithKline (GSK), London, UK; Pfizer, NY; and Boehringer, Binger Str, Ingelheim, Germany. A Mangel is an employee of RTI Health Solutions, Research Triangle Park, NC. RTI Health Solutions met the costs for preparation of this manuscript. G Hicks is an employee of Tioga Pharmaceuticals.

References

- 1.Everhart JE, Renault PF. Irritable bowel syndrome in office-based practices in the United States. Gastroenterology. 1991;100(4):998–1005. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(91)90275-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Russo MW, Gaynes BN, Drossman DA. A national survey of practice patterns of gastroenterologists with comparison to the past two decades. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1992;29(4):339–343. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199912000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mayer EA. Clinical practice. Irritable bowel syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(16):1692–1699. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp0801447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Watson ME, Lacey L, Kong S, et al. Alosetron improves quality of life in women with diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96(2):455–459. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03525.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wells NE, Hahn BA, Whorwell PJ. Clinical economics review: irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1997;11(6):1019–1030. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1997.00262.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Whitehead WE, Burnett CK, Cook EW, III, Taub E. Impact of irritable bowel syndrome on quality of life. Dig Dis Sci. 1996;41(11):2248–2253. doi: 10.1007/BF02071408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Corney RH, Stanton R. Physical symptom severity, psychological and social dysfunction in a series of outpatients with irritable bowel syndrome. J Psychosom Res. 1990;34(5):483–491. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(90)90022-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hahn BA, Yan S, Strassels S. Impact of irritable bowel syndrome on quality of life and resource use in the United States and United Kingdom. Digestion. 1999;60(1):77–81. doi: 10.1159/000007593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Andrews EB, Eaton SC, Hollis KA, et al. Prevalence and demographics of irritable bowel syndrome: results from a large web-based survey. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;22(10):935–942. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02671.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patel RP, Petitta A, Fogel A, Peterson E, Zarowitz BJ. The economic impact of irritable bowel syndrome in a managed care setting. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2002;35(1):14–20. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200207000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Levy RL, Von Korff M, Whitehead WE, et al. Costs of care for irritable bowel syndrome in a health maintenance organization. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96(11):3122–3129. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.05258.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sandler RS. Epidemiology of irritable bowel syndrome in the United States. Gastroenterology. 1990;99(2):409–415. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(90)91023-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Drossman DA, Li Z, Andruzzi E, et al. U.S. householder survey of functional gastrointestinal disorders. Prevalence, sociodemography, and health impact. Dig Dis Sci. 1993;38(9):1569–1580. doi: 10.1007/BF01303162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hungin AP, Whorwell PJ, Tack J, Mearin F. The prevalence patterns and impact of irritable bowel syndrome: an international survey of 40,000 subjects. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;17(5):643–650. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2003.01456.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Longstreth GF, Thompson WG, Chey WD, Houghton LA, Mearin F, Spiller RC. Functional bowel disorders. In: Drossman DA, Corazziari E, Delvaux M, et al., editors. Rome III: The Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders. McLean, VA: Degnon Associates Inc; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mangel AW, Northcutt AR. Review article: the safety and efficacy of alosetron, a 5-HT3 receptor antagonist, in female irritable bowel syndrome patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1999;13(Suppl 2):77–82. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1999.00010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Camilleri M, Chey WY, Mayer EA, et al. A randomized controlled clinical trial of the serotonin type 3 receptor antagonist alosetron in women with diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Arch Int Med. 2001;161(14):1733–1740. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.14.1733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pimentel M, Lembo A, Chey WD, et al. for TARGET Study Group. Rifaximin therapy for patients with irritable bowel syndrome without constipation. N Eng J Med. 2011;364(1):22–32. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1004409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pimentel M, Lembo A, Chey WD, et al. for TARGET Study Group. Rifaximin therapy for patients with irritable bowel syndrome without constipation. N Eng J Med. 2011;364(1) doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1004409. Supplementary Appendix. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tack J, Müller-Lissner S, Bytzer P, et al. A randomised controlled trial assessing the efficacy and safety of repeated tegaserod therapy in women with irritable bowel syndrome with constipation. Gut. 2005;54(12):1707–1713. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.070789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Müller-Lissner SA, Fumagalli I, Bardhan KD, et al. Tegaserod, a 5-HT(4) receptor partial agonist, relieves symptoms in irritable bowel syndrome patients with abdominal pain, bloating and constipation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2001;15(10):1655–1666. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2001.01094.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Drossman DA, Chey WD, Johanson JF, et al. Clinical trial: lubiprostone in patients with constipation-associated irritable bowel syndrome – results of two randomized, placebo-controlled studies. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;29(3):329–341. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03881.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnston JM, Kurtz CB, Macdougall JE, et al. Linaclotide improves abdominal pain and bowel habits in a phase IIb study of patients with irritable bowel syndrome with constipation. Gastroenterology. 2010;139(6):1877–1886. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.08.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.American College of Gastroenterology Task Force on Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Brandt LJ, Chey WD, Foxx-Orenstein AE, et al. An evidence- based position statement on the management of irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104(Suppl 1):S1–S35. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2008.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Walsh SL, Strain EC, Abreu ME, Bigelow GE. Enadoline, a selective kappa opioid agonist: comparison with butorphanol and hydromorphone in humans. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2001;157(2):151–162. doi: 10.1007/s002130100788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barber A, Bartoszyk GD, Bender HM, et al. A pharmacological profile of the novel, peripherally-selective kappa-opioid receptor agonist, EMD 61753. Br J Pharmacol. 1994;113(4):1317–1327. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1994.tb17142.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Su X, Joshi SK, Kardos S, Gebhart GF. Sodium channel blocking actions of the kappa-opioid receptor agonist U50,488 contribute to its visceral antinociceptive effects. J Neurophysiol. 2002;87(3):1271–1279. doi: 10.1152/jn.00624.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Joshi SK, Lamb K, Bielefeldt K, Gebhart GF. Arylacetamide kappa-opioid receptor agonists produce a tonic- and use-dependent block of tetrodotoxin-sensitive and -resistant sodium currents in colon sensory neurons. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;307(1):367–372. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.052829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jonker JW, Wagenaar E, van Deemter L, et al. Role of blood-brain barrier P-glycoprotein in limiting brain accumulation and sedative side-effects of asimadoline, a peripherally acting analgesic drug. Br J Pharmacol. 1999;127(1):43–50. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barber A, Gottschlich R. Novel developments with selective, nonpeptidic kappa-opioid receptor agonists. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 1997;6(10):1351–1368. doi: 10.1517/13543784.6.10.1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bender HM, Dasenbrock J. Brain concentrations of asimadoline in mice: the influence of coadministration of various P-glycoprotein substrates. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1998;36(2):76–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Slizgi GR, Ludens JH. Studies on the nature and mechanism of the diuretic activity of the opioid analgesic ethylketocyclazocine. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1982;220(3):585–591. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rimoy GH, Bhaskar NK, Wright DM, Rubin PC. Mechanism of diuretic action of spiradoline (U-62066E) – a kappa-opioid receptor agonist in the human. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1991;32(5):611–615. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1991.tb03960.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brooks DP, Giardina G, Gellai M, et al. Opiate receptors within the blood-brain barrier mediate kappa agonist-induced water diuresis. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1993;266(1):164–171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ashton N, Balment RJ, Blackburn TP. Kappa-opioid-receptor agonists modulate the renal excretion of water and electrolytes in anaesthetized rats. Br J Pharmacol. 1990;99(1):181–185. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1990.tb14674.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kramer HJ, Uhl W, Ladstetter B, Bäcker A. Influence of asimadoline, a new kappa-opioid receptor agonist, on tubular water absorption and vasopressin secretion in man. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2000;50(3):227–235. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.2000.00256.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jordan B, Devi LA. Molecular mechanisms of opioid receptor signal transduction. Br J Anaesth. 1998;81(1):12–19. doi: 10.1093/bja/81.1.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.North RA. Opioid receptor types and membrane ion channels. Trends Neurosci. 1986;9:114–117. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Herz A. Peripheral opioid analgesia – facts and mechanisms. Prog Brain Res. 1996;110:95–104. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(08)62567-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Diop L, Rivière PJ, Pascaud X, Junien JL. Peripheral kappa-opioid receptors mediate the antinociceptive effect of fedotozine (correction of fetodozine) on the duodenal pain reflex in rat. Eur J Pharmacol. 1994;271(1):65–71. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(94)90265-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Harada Y, Nishioka K, Kitahata LM, Nakatani K, Collins JG. Contrasting actions of intrathecal U50, 488H, morphine, or [D-Pen2, D-Pen5] enkephalin or intravenous U50, 488H on the visceromotor response to colorectal distension in the rat. Anesthesiology. 1995;83(2):336–343. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199508000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Danzebrink RM, Green SA, Gebhart GF. Spinal mu and delta, but not kappa, opioid-receptor agonists attenuate responses to noxious colorectal distension in the rat. Pain. 1995;63(1):39–47. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(94)00275-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sengupta JN, Su X, Gebhart GF. Kappa, but not mu or delta, opioids attenuate responses to distention of afferent fibers innervating the rat colon. Gastroenterology. 1996;111(4):968–980. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(96)70064-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Su X, Sengupta JN, Gebhart GF. Effects of kappa-opioid receptor-selective agonists on responses of pelvic nerve afferents to noxious colorectal distension. J Neurophysiol. 1997;78(2):1003–1012. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.78.2.1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Delvaux M, Beck A, Jacob J, et al. Effect of asimadoline, a kappa opioid agonist, on pain induced by colonic distension in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20(2):237–246. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.01922.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rivière PJ. Peripheral kappa-opioid agonists for visceral pain. Br J Pharmacol. 2004;141(8):1331–1334. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sengupta JN, Snider A, Su X, Gebhart GF. Effects of kappa opioids in the inflamed rat colon. Pain. 1999;79(2–3):175–185. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(98)00175-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Burton MB, Gebhart GF. Effects of kappa-opioid receptor agonists on responses to colorectal distension in rats with and without acute colonic inflammation. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1998;285(2):707–715. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Walker JS, Scott C, Bush KA, Kirkham BW. Effects of the peripherally selective kappa-opioid asimadoline, on substance P and CGRP mRNA expression in chronic arthritis of the rat. Neuropeptides. 2000;34(3–4):193–202. doi: 10.1054/npep.2000.0813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Binder W, Scott C, Walker JS. Involvement of substance P in the anti-inflammatory effects of the peripherally selective kappa-opioid asimadoline and the NK1 antagonist GR205171. Eur J Neurosci. 1999;11(6):2065–2072. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00625.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Berg KA, Rowan MP, Sanchez TA, et al. Regulation of κ-opioid receptor signaling in peripheral sensory neurons in vitro and in vivo. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2011;338(1):92–99. doi: 10.1124/jpet.110.177493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bi J, Tsai NP, Lin YP, Loh HH, Wei LN. Axonal mRNA transport and localized translational regulation of kappa-opioid receptor in primary neurons of dorsal root ganglia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(52):19919–19924. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607394104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bi J, Tsai NP, Lu HY, Loh HH, Wei LN. Copb1-facilitated axonal transport and translation of kappa opioid-receptor mRNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(34):13810–13815. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703805104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tsai NP, Bi J, Loh HH, Wei LN. Netrin-1 signaling regulates de novo protein synthesis of kappa opioid receptor by facilitating polysomal partition of its mRNA. J Neurosci. 2006;26(38):9743–9749. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3014-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tsai NP, Bi J, Wei LN. The adaptor Grb7 links netrin-1 signaling to regulation of mRNA translation. EMBO J. 2007;26(6):1522–1531. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Delgado-Aros S, Chial HJ, Camilleri M, et al. Effects of a kappa-opioid agonist, asimadoline, on satiation and GI motor and sensory functions in humans. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2003;284(4):G558–G566. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00360.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mangel AW, Bornstein JD, Hamm LR, et al. Clinical trial: asimadoline in the treatment of patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;28(2):239–249. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03730.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chamouard P, Klein A, Martin E, Adloff M, Angel F. Regulatory role of enteric kappa opioid receptors in human colonic motility. Life Sci. 1993;53(14):1149–1156. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(93)90551-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Giuliani S, Lecci A, Tramontana M, Maggi CA. Role of kappa opioid receptors in modulating cholinergic twitches in the circular muscle of guinea-pig colon. Br J Pharmacol. 1996;119(5):985–989. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15768.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Poonyachoti S, Kulkarni-Narla A, Brown DR. Chemical coding of neurons expressing delta- and kappa-opioid receptor and type I vanilloid receptor immunoreactivities in the porcine ileum. Cell Tissue Res. 2002;307(1):23–33. doi: 10.1007/s00441-001-0480-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bagnol D, Mansour A, Akil H, Watson SJ. Cellular localization and distribution of the cloned mu and kappa opioid receptors in rat gastrointestinal tract. Neuroscience. 1997;81(2):579–591. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00227-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sternini C, Patierno S, Selmer IS, Kirchgessner A. The opioid system in the gastrointestinal tract. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2004;16(Suppl 2):3–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-3150.2004.00553.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pol O, Palacio JR, Puig MM. The expression of delta- and kappa-opioid receptor is enhanced during intestinal inflammation in mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;306(2):455–462. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.049346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kellow JE, Phillips SF. Altered small bowel motility in irritable bowel syndrome is correlated with symptoms. Gastroenterology. 1987;92(6):1885–1893. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(87)90620-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Marciani L, Cox EF, Hoad CL, et al. Postprandial changes in small bowel water content in healthy subjects and patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2010;138(2):469–477. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.10.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Deiteren A, Camilleri M, Burton D, McKinzie S, Rao A, Zinsmeister AR. Effect of meal ingestion on ileocolonic and colonic transit in health and irritable bowel syndrome. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55(2):384–391. doi: 10.1007/s10620-009-1041-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chey WY, Jin HO, Lee MH, Sun SW, Lee KY. Colonic motility abnormality in patients with irritable bowel syndrome exhibiting abdominal pain and diarrhea. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96(5):1499–1506. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03804.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bouchoucha M, Devroede G, Raynaud JJ, Bon C, Bejou B, Benamouzig R. Is the colonic response to food different in IBS in contrast to simple constipation or diarrhea without abdominal pain? Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56(10):2947–2956. doi: 10.1007/s10620-011-1700-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mangel AW, Williams VS. Asimadoline in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2010;19(10):1257–1264. doi: 10.1517/13543784.2010.515209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Szarka L, Camilleri M, Burton D, et al. Efficacy of on-demand asimadoline, a peripheral k-opioid agonist, in females with irritable bowel syndrome. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5(11):1268–1275. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Camilleri M. Novel pharmacology: asimadoline, a kappa-opioid agonist, and visceral sensation. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2008;20(9):971–979. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2008.01183.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]