Abstract

Among those who are sexually active, condom use is the only method of protection against HIV/AIDS. Poor condom skills may lead to condom use failures, which can lead to risk of exposure. Despite the wide availability of condom use instructional leaflets, it is unclear whether these instructions sufficiently teach condom use skills. Ninety-two male and 113 female undergraduates were randomly assigned to a control condition (read non-condom instructions) or a treatment condition (read condom instructions). Participants completed self-report measures related to condom use and performed a condom demonstration task. Participants who read the condom instructions did not perform significantly better on the demonstration task, F (1, 203) = 2.90, P = 0.09, η2 = 0.014. At the item level, those who read the condom instructions better performed two of the seven condom use steps correctly. These data suggest that condom packaging instructions do not effectively teach condom use skills.

Keywords: condom skills, MOCUS, condom demonstration, condom instruction

Introduction

With over 50,000 new cases of HIV in the US each year1 and approximately 2.6 million worldwide,2 researchers continue their efforts to identify best practices for risk prevention. Because condom use is the only method of protection against HIV among those who are sexually active, many prevention programs are designed to increase consistent and correct condom use. Unfortunately, many condom users may be unwilling to attend an instructional program or may not have access to one. And thus, in the absence of formal condom use instruction or training, users may rely on alternative methods to learn correct condom use.

The most available means through which users may learn correct condom usage is via instructional leaflets included in condom packaging. Despite the availability of these instructions, it is unclear to what extent users read and follow the instructions or if these leaflets effectively instruct correct condom usage. In fact, a review of the literature yielded no such evaluations.

There is also evidence that condom users are experiencing failures at a much higher rate than would be expected (ie, relative to condom laboratory tests). Norris and Ford3 found that 60% of their sample reported having experienced a condom breaking, and Crosby and colleagues4 reported that over one-third of adolescents experienced a failure in the past 3 months. Similarly, Lindemann5 found that 47% of college students reported experiencing at least one condom use failure in the past 6 months, and 13% experienced at least one failure in the past 30 days.

Other researchers have estimated that approximately 13% of all condom uses result in failure.6 When one considers that each instance of condom failure places both partners at risk, the importance of minimizing such failures becomes second only to encouraging consistent condom use in the first place.

Condoms are highly effective, but only when used correctly. The importance of correct condom use is well recognized by condom manufacturers; for example, Trojan® brand latex condoms come with the following statement: “For maximum benefits, it is important to follow the instructions for use … Failure to do so may result in the loss of the benefits of a condom.” The high rates of condom failure reported may be attributed at least in part due to condom use error,7,8 and one’s personal ability to use a condom correctly may be a consideration when weighing the benefits and costs of condom use.9 In addition, having negative experiences with condoms, such as a condom failure, may result in negative beliefs toward condom use, which in turn may decrease intentions to use condoms in the future.3 Likewise, condom use has been associated with high condom use self-efficacy and pro-condom norms.10

The importance of increasing correct condom use skills is fundamental to ongoing efforts to reduce transmission of HIV. The purpose of this research was to assess the efficacy of written condom packaging instructions for teaching correct condom use skills. More specifically, we compared condom use skills between college students who read condom packaging instructions immediately prior to performing a condom demonstration task to those who did not.

Methods

Participants

Participants were 92 male and 113 female undergraduate students ranging in age from 18 to 42 years (M = 19.36, SD = 2.63). Participants were predominately white (81%) and attending their freshmen or sophomore year of college (80%). Among the participants, 91% reported ever having sexual intercourse, and among those, 89% reported ever using a condom (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparison of demographic, sexual, and condom use variables between the condom packaging instructions and control groups

| Variable | Packaging instructions | Control group |

|---|---|---|

| n | 102 | 103 |

| % male | 47.1 | 42.7 |

| Mean age (SD) | 19.08 (3.62) | 19.27 (1.73) |

| % white ethnicity | 84.7 | 79.6 |

| % sexually active (ever) | 90.6 | 91.3 |

| % used condom (ever) | 89.7 | 88.2 |

| % experienced condom failure (ever) | 43.6* | 62.2 |

| % responsible for condom application | 54.1 | 47.5 |

| Mean (SD) Condom Use Self-Efficacy Score | ||

| Condom mechanics | 3.86 (0.96) | 3.77 (1.02) |

| Personal disapproval | 4.62 (0.55) | 4.69 (0.64) |

| Assertive | 4.53 (0.62) | 4.50 (0.72) |

| Intoxicants | 4.07 (0.92) | 4.14 (0.96) |

| % intend to use condoms in the future | 90.2 | 94.6 |

Participants were recruited using a departmental human subjects pool, where students signed up for research participation opportunities in a central, public location, and for which participation earned credit toward meeting an introductory psychology research experience requirement. The use of human participants in this research was approved by the university’s Institutional Review Board.

Measures and materials

Condom use skills were assessed using the Measure of Observed Condom Use Skills (MOCUS).11,12 The MOCUS assesses seven singular, directly observable behaviors toward correct condom usage (see Table 2 for individual items). Items are scored as performed correctly (“yes”) or not (“no”). All items on the MOCUS are behaviors that prevent condom breakage, slippage, or leakage of fluids. The MOCUS has high Guttman scalability (Reproducability = 0.93; Plus Percentage Ratio = 0.75). The MOCUS was administered individually by one of four trained observers (two male and two female). Inter-observer agreement was 93% from 18 pilot participants as part of the training, and the average chance-adjusted agreement across the seven MOCUS items was Cohen’s κ = 0.78.

Table 2.

Percentage of participants who correctly performed each MOCUS item by group

| MOCUS item | % correct | RR | 95% CI of RR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control group | Packaging instructions | |||

| 1) Without using fingernails or teeth, open condom packaging by tearing along edge | 80.6 | 71.6 | 0.89 | 0.76–1.04 |

| 2) Place condom right-side out on penis | 89.3 | 85.3 | 0.96 | 0.86–1.06 |

| 3) Pinch reservoir tip with two fingers | 49.5 | 72.5 | 1.47* | 1.17–1.84 |

| 4) Roll condom down the penis until reaching the base | 89.3 | 95.1 | 1.06 | 0.98–1.15 |

| 5) Hold condom at base and remove penis from the partner | 43.7 | 61.8 | 1.41* | 1.08–1.85 |

| 6) Pinch tip of condom so that ejaculate is in the tip | 49.5 | 52.0 | 1.05 | 0.80–1.37 |

| 7) Holding condom at both tip and base, carefully slide the condom off the penis | 53.4 | 52.0 | 0.97 | 0.75–1.26 |

Notes: RRs above one indicate better performance among those in the Packaging Instructions Group, RRs around one indicate no difference between groups, and RRs below one indicate better performance in the Control Group.

P < 0.05.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; RR, risk ratio.

In addition to the MOCUS, participants responded to self-report measures related to condom use. The Reported Condom Use and Failures scale (RCUF, unpublished measure) was used to assess the frequency and types of condom use failures experienced in the recent past, the Sexual Behavior Survey13 was used to assess current sexual practices, such as the number of recent sexual partners, and the Condom Use Self-Efficacy Scale (CUSES)14 was used as an indirect measure of skill, communication, and confidence with condoms. The CUSES was scored using the four self-efficacy subscales identified with acceptable internal consistency (α ≈ 0.80): (1) condom mechanics, (2) partner’s disapproval, (3) assertiveness, and (4) intoxicants. 15 Internal consistency estimates for the present sample were similar, α > 0.70.

Instructional pamphlets showing correct condom application and removal steps (Trojan brand condoms) and correct yoga-ball exercises20 (from http://www.about.com) were used. The pamphlets were similar in that they both contained small illustrations alongside step-by-step instructions for completing a physical procedure. Written instructions were provided in both English and Spanish for both condom application and removal, and yoga-ball exercises. In addition, lubricated condoms and a wooden penile model were used during administration of the MOCUS.

The Trojan brand condom use leaflet included three application illustrations, showing the package being torn open, the condom placed on the tip of the penis, and the condom being pinched at the tip while being unrolled to the pubic hair line. There was also a fourth illustration showing that the condom should be held at the base of the penis during removal from the partner. The images and written instructions on the pamphlet clearly coincided with six of the seven items on the MOCUS. For the remaining item (Item 7, referring to holding condom at both tip and base while carefully sliding the condom off the penis) the pamphlet included a related, but more general instruction to hold the condom on the penis during the entire removal process.

Design and procedure

A between-subjects design was employed where participants in the Control Group read a non-condom related instructional pamphlet (ie, correct yoga-ball exercises) and participants in the Treatment Group read the condom packaging instructional pamphlet. Participants were randomly assigned to the group based on the research session and sex of the MOCUS observer. Random assignment based on the research session was used to prevent diffusion of treatment, and random assignment by MOCUS observer sex was used to ensure that the number of same sex and different sex participant-observer interactions were equivalent for both treatment groups.

Upon arrival to the research session, participants provided written informed consent. At that time, participants were given the packet of self-report measures and instructed to generate a unique continuity code,16,17 which was written on the packet and a white file folder label (to be placed on the MOCUS at a later time). This continuity code procedure has been used to maintain anonymity of responses for sensitive data and allows researchers to link together multiple, independent data records for a particular participant. After completing the self-report measures, participants were given either the condom packaging or yoga-ball instructions and asked to carefully read the content. A researcher observed each participant as he or she read the assigned instructions.

After reading the instructions, participants were escorted to a private room by a trained observer where the MOCUS was administered. All observers were blind to which instructions the participant had read. Participants were asked to respond to four self-report questions related to the MOCUS and were provided a written debriefing form that included the correct steps to condom usage. Before leaving, the researcher offered to answer questions and thanked each participant for their time.

Efficacy measures and data analysis

Three efficacy measures were derived to evaluate the impact of condom packaging instructions on condom use skills. First, mean MOCUS scores were used as an aggregate efficacy measure to compare those who read the condom packaging instructions (ie, Packaging Instructions Group) and those who read the yoga-ball instructions (ie, Control). Second, the proportion of participants who correctly performed each item on the MOCUS was compared between groups to identify which, if any, aspects of condom use were best learned from reading the packaging instructions. A third efficacy measure was created by comparing the proportion of packaging instructions and control participants who performed all seven MOCUS items correctly. As each item on the MOCUS is designed to prevent a specific type of condom use failure,11 this third efficacy measure was important because only those who correctly perform all aspects of condom application and removal minimize the risk of condom use failures (eg, breakage, leakage, slippage).

Data analysis proceeded in two phases. Initially, the three efficacy measures were compared between the Packaging Instructions and Control Groups. The same measures were then reexamined separately for men and women to account for potential gender differences in MOCUS scores that have been reported previously.11,12 ANOVA was used to compare the mean MOCUS scores between groups and to test for potential gender differences in MOCUS scores and differential effects of reading condom packaging instructions (ie, Gender X Group Interaction). Proportion data were compared using risk ratios (RRs). RRs represent the proportion of packaging instructions participants who successfully performed each item (or all MOCUS items) relative to the proportion of control participants. The RR was used because it summarizes two proportions with a readily interpretable ratio (eg, an RR of 1.50 indicates that packaging instructions participants were 50% more likely to successfully perform that particular MOCUS item) and associated confidence intervals could be compared to test for potential gender differences. RRs with non-overlapping confidence intervals would indicate differential effects of condom packaging instructions between genders.

Results

Table 1 displays the demographic composition, reported sexual experiences, and CUSES for the Packaging Instructions and Control Groups. Participants in both groups were similar in age, gender, ethnic composition, mean CUSES scores, sexual and condom use experiences, with one exception. Among those who reported ever using condoms, a greater proportion of control participants reported experiencing at least one condom use failure (62.2%) than those who read the packaging instructions (43.6%) (χ2 [1, n = 160] = 5.56, P = 0.02). No other differences between groups were significant.

Efficacy of condom packaging instructions

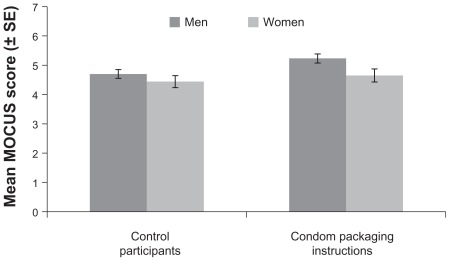

As can be seen in Figure 1, the mean MOCUS score among those in the Packaging Instructions Group was higher than that in the Control Group. This difference was modest and amounted to an average of approximately one-third of a MOCUS item better performance for the Packaging Instructions Group (ie, approximately one-quarter of a standard deviation) and was non-significant (F[1, 203] = 2.90, P = 0.09, η2 = 0.014). The proportion of participants who correctly performed each MOCUS item provides greater detail regarding this mean difference.

Figure 1.

Those who read the condom packaging instructions performed approximately one-third of an item better on the Measure of Observed Condom Use Skills (MOCUS) than those in the control group.

Note: This difference was modest (Cohen’s d = 0.23) and non-significant, P = 0.09.

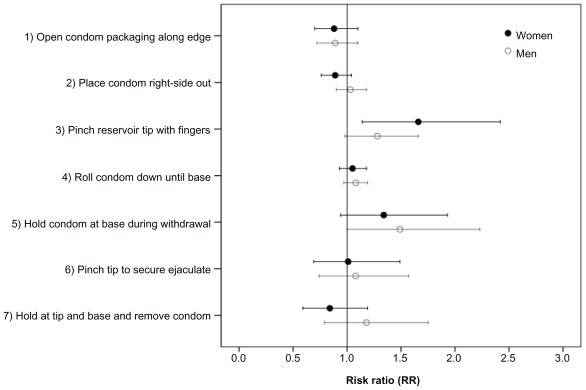

As can be seen in Table 2, those who read the packaging instructions performed significantly better on two of the seven MOCUS items. Participants who read the packaging instructions were nearly 1.5 times more likely to successfully complete Application Step 3 (ie, “Pinch reservoir tip with two fingers”) and Removal Step 5 (ie, “Hold condom at base and remove penis from the partner”), χ2’s were 11.43 (P = 0.001) for Item 3 and 6.72 (P = 0.01) for Item 5. No significant differences were observed between groups on the remaining MOCUS items.

Overall, 16.1% of participants performed all seven MOCUS items correctly. Although this proportion was slightly higher among the Packaging Instruction (18.6%) than the Control Group (13.6%), the difference was non-significant (χ2 [1, N = 205] = 0.96, P = 0.33) and small on a relative basis (RR: 1.37, 95% CI: 0.72–2.58).

Gender differences in the efficacy of condom packaging instructions

A two-way ANOVA was used to compare mean MOCUS scores between men and women and to test for differential impact of the condom packaging instructions between genders. On average, men performed approximately one-half of a MOCUS item (M = 4.98, SD = 1.46) better than women (M = 4.54, SD = 1.69). This difference amounted to approximately one-quarter of a standard deviation (Cohen’s d = 0.28) and was non-significant (F[1, 201] = 3.81, P = 0.052, η2 = 0.019). As described above and displayed in Figure 1, the Packaging Instructions Group performed slightly better than the Control Group; however, the instructions were equally effective for men and women, Group × Gender interaction of F (1, 201) = 0.54 (P = 0.47, η2 = 0.003).

Reading the packaging instructions had a similar impact for men and women when viewed item-by-item as well. Figure 2 displays the RRs comparing the proportion of participants in the Packaging Instructions Group who successfully performed each item relative to control participants for both men and women. As can be seen in Figure 2, the RRs are similar for all seven MOCUS items, and the 95% confidence intervals display considerable overlap between genders.

Figure 2.

Relative risk ratios (RR) for each Measure of Observed Condom Use Skills (MOCUS) item by gender.

Notes: Error bars represent the 95% confidence interval. Risk ratio (RR) above one (solid vertical line) indicate better performance among those in the Packaging Instructions Group, RRs around one indicate no difference between groups, and RRs below one indicate better performance in the Control Group. The overlapping confidence intervals for all seven MOCUS items suggests that the effect of reading condom packaging instructions was similar for both genders. MOCUS items have been abbreviated for presentation; see Table 2 for complete items.

The overall percentage of men (19.6%) and women (13.3%) who correctly performed all seven MOCUS items was also similar (χ2[1, N = 205] = 1.49, P = 0.22). The relative proportion of the Packaging Instructions (men: 25.0%; women: 13.0%) and Control Groups (men: 13.4%; women: 13.6%) showed that men in the Packaging Instructions Group were nearly twice as likely to score perfectly on the MOCUS (RR: 1.84, 95% CI: 0.75–4.46) than men in the Control Group. Women in the Packaging Instructions Group, on the other hand, were no more likely to score perfectly on the MOCUS than those in the Control Group (RR: 0.96, 95% CI: 0.37–2.46). It should be noted, however, that due to the small number of participants who scored perfectly on the MOCUS, irrespective of gender, the confidence intervals around the RR were wide and overlapped substantially.

Discussion

Participants who read a name-brand condom packaging instructional leaflet did not demonstrate significantly better condom use skills and were more likely to correctly perform only two of seven individual condom use steps on the MOCUS. In addition, the effect of reading the condom packaging instructions were similar for men and women on both an aggregate and an item-by-item basis. Lastly, only a small percentage of participants demonstrated errorless condom use (ie, perfect score on the MOCUS), irrespective of their group assignment. As such, these data suggest that condom packaging instructions alone do not provide sufficient information to teach errorless condom use. Because users may rely on these packaging instructions, it is important to ensure that they include the necessary information in a way that leads to correct condom usage.

Although many of the differences between groups failed to reach statistical significance, there was a promising trend toward slightly better condom use skills among those who read condom packaging instructions. More specifically, the one-third of a MOCUS step difference observed for the aggregate efficacy measure can be attributed to the increased proportion of packaging instructions participants who correctly performed two of the seven condom use steps. As these two steps were among the least correctly performed by control participants, the greater than 40% improvement for those who read the packaging instructions becomes especially notable. Moreover, with Item 3 (ie, “Pinch reservoir tip with two fingers”) designed to minimize condom breakage and Item 5 (“Hold condom at base as condom is removed from partner”) designed to minimize slippage, correctly performing these steps reduces the risk of two different types of condom use failure. Despite this promising improvement, only two-thirds of participants correctly performed these steps immediately after reading the packaging instructions and these two steps alone are not sufficient to prevent condom use failures. The importance of this later issue is further echoed by the fraction of participants (16%) who completed all seven condom application and removal steps correctly. This may be, at least in part, due to characteristics of the written instructions, and researchers and condom companies should consider research outcomes on effective written instructions for procedural tasks when developing new leaflets.18 Similarly, it would be beneficial to identify how written condom instructions can be improved. For example, leaflets may be improved by using larger font, more images, or clearer and more detailed images. These features may be most important to users who have difficulty reading, or difficulty reading small font, or for those whose native language is other than that used in the leaflet.

Potentially meaningful improvements to the content of condom packaging instructions may also be ascertained from the present study. More specifically, of the seven total MOCUS items only four items were performed correctly by approximately one-half of control participants (ie, Items 3, 5, 6, and 7; see Table 1). In contrast, approximately 85% of control and condom packaging participants successfully completed the remaining three items (ie, Items 1, 2, and 4). These data suggest that areas with the greatest potential for improvement would be (a) pinching the reservoir tip with two fingers prior to application (Item 3), (b) holding the condom at the base of the penis while removing the penis from the partner (Item 5), (c) pinching the tip of the condom to secure ejaculate in the reservoir (Item 6), and (d) holding the condom at both the tip and base while removing the condom (Item 7). Performance on two of these four items with the greatest potential for improvement was, in fact, better among those who read the condom packaging instructions (ie, pinching the reservoir tip prior to application and holding the condom at the base while removing the penis from the partner). Moreover, if only these four items with the greatest for potential improvement are considered, the significant performance difference on Items 3 and 5 translates to a significant mean difference between the Condom Packaging and Control Groups (F[1, 203] = 5.43, P = 0.02, η2 = 0.026). As such, the overall finding of a non-significant difference between groups on the aggregate MOCUS score (based on all seven items) should be considered in light of key differences between groups on two of the four items with the lowest performance overall and, perhaps more importantly, the greatest potential for improvement in the first place.

The low percentage of participants who correctly applied and removed the condom is particularly surprising given our sample of college students, most of whom were sexually active and endorsed past condom use and intentions to use condoms in the future. Because every item on the MOCUS assesses a behavior related to a condom use failure, errorless performance is ideal for risk prevention. These data suggest that condom users who rely on similar written instructional materials as those tested here may be increasing their risk of experiencing a condom use failure. As further evidence of this problem, approximately one-half of the sample reported experiencing at least one condom use failure. This finding is consistent with other reports of condom use failures3–5 and the small number of participants who correctly applied and removed the condom in the present study offers a potential explanation for the generally high number of reported condom use failures.

In considering the implications of these findings, the reader should also be aware of some limitations. First, only one set of condom use instructions were used in the present study. Although Trojan brand condoms comprise approximately 75% of condom sales19 and that competing brands include similar instructions as part of their packaging, it is possible that a different set of instructions may have yielded different results. Second, despite being equivalent on a number of key demographic and sexual history variables, the proportion of participants who reported experiencing a condom use failure was slightly higher among the randomly assigned Packaging Instructions Group. It should be noted, however, that this difference did not translate to corresponding differences in self-efficacy for a number of condom use factors, including the mechanics of condom application and removal, nor to differences in intentions to use condoms in the future. Similarly, prior and recent exposure to condom use instruction was not assessed in this study, which may present a potential alternative explanation for these findings if differences in exposure to condom use instructions existed between groups prior to the study. However, as noted above, random assignment was employed to minimize the possibility of such preexisting differences and the groups were similar on a variety of relevant demographic and sexual history variables (see Table 1). Also, the single-shot, cross-sectional nature of the current design permits conclusions regarding group differences. An alternative design, such as a pre-post design, may permit stronger conclusions regarding learning or skill improvements from written condom packaging instructions. Lastly, this study assessed the effect on condom packaging instructions on the behavior of college students, and it is unclear if the instructions would be more or less effective with other populations, such as men who have sex with men, injection drug users, or sexually active adolescents. Including others in future research would provide a more complete understanding of the efficacy of condom packaging instructions across populations.

This research served as an initial evaluation as to whether or not college students can demonstrate correct condom use skills after reading published condom packaging instructional leaflets. Considerations for future research are many. There exists a need to evaluate the effectiveness of instructional leaflets published by other brands, as their content may better inform correct condom usage. It also remains unclear whether other populations effectively learn condom use skills from these pamphlets. If these findings are replicated using different instructional leaflets or among other populations, then efforts should be focused on improving packaging instructions. Also, with the continued increase and availability of technology, consideration should be given to assessing the effectiveness and feasibility of alternative types of instructions, such as video demonstrations that can be downloaded to mobile phones.

This research strengthens the literature documenting the high frequency on condom use failures, in this case, among college students. Clearly, there is need to reduce the frequency of these failures, and this study provides evidence that condom use skills are lacking, even among condom using college students, and also that current instructional leaflets are not adequate for those looking to learn correct condom use skills. Nonetheless, these data show that instructional leaflets do help with two specific condom use steps, and provide promise that if improved, instructional leaflets may become an effective, low-cost, and easily distributed approach to reducing condom use failures – an accomplishment that may go far toward our efforts to reduce HIV risk.

Acknowledgment

The authors wish to thank Thomas Brigham for his insights while providing feedback on the manuscript and who generously donated his time to helping us.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflict of interests in this work.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Divisions of HIV Prevention and the National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention. HIV Incidence. 2008. [Accessed December 30, 2011]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/surveillance/print/incidence.htm.

- 2.National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), National Institutes of Health. HIV/AIDS Quick Facts. 2011. [Accessed December 30, 2011]. Available from: http://www.niaid.nih.gov/topics/HIVAIDS/understanding/pages/quickfacts.aspx.

- 3.Norris AE, Ford K. Associations between condom experiences and beliefs, intentions, and use in a sample of urban, low-income, African-American and Hispanic youth. AIDS Educ Prev. 1994;6(1):27–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crosby RA, DiClemente RJ, Wingood GM, et al. Condom failure among adolescents: implications for STD Prevention. J Adolesc Health. 2005;36:534–536. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lindemann DF. Comparing two condom use components of a HIV/AIDS intervention for college students (Doctoral Dissertation) Retrieved from Washington State University; Pullman, WA: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Warner L, Clay-Warner J, Boles J, Williamson J. Assessing condom use practices. Implications for evaluating method and user effectiveness. Sex Transm Dis. 1998;25(6):273–277. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199807000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kelly JA. Changing HIV Risk Behavior: Practical Guide. New York: Guilford; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yarber WL, Graham CA, Sanders SA, Crosby RA. Correlates of condom breakage and slippage among university undergraduates. Int J STD AIDS. 2004;15(7):467–472. doi: 10.1258/0956462041211207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Catania JA, Dolcini MM, Coates TJ, et al. Predictors of condom use and multiple partnered sex among sexually-active adolescent women: Implications for AIDS-related health interventions. J Sex Res. 1989;26(4):514–524. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kalichman S, Stein JA, Malow R, et al. Predicting protected sexual behaviour using the Information-Motivation-Behaviour skills model among adolescent substance abusers in court-ordered treatment. Psychol Health Med. 2002;7(3):327–338. doi: 10.1080/13548500220139368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lindemann DF, Brigham TA. A Guttman scale to assess condom use skills among college students. AIDS Behav. 2003;7(1):23–27. doi: 10.1023/a:1022505205852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lindemann DF, Brigham TA, Harbke C, Alexander T. Toward errorless condom use: a comparison of two courses to improve condom use skills. AIDS Behav. 2005;9(4):451–457. doi: 10.1007/s10461-005-9017-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Horn P, Brigham TA. A self-management approach to reduce AIDS risk in sexually active heterosexual college students. Behav Soc Issues. 1996;6(1):3–21. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brafford LJ, Beck KH. Development and validation of a condom self-efficacy scale for college students. J Am Coll Health. 1991;39(5):219–225. doi: 10.1080/07448481.1991.9936238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brien TM, Thombs DL, Mahoney CA, Wallnau L. Dimensions of self-efficacy among three distinct groups of condom users. J Am Coll Health. 1994;42(4):167–174. doi: 10.1080/07448481.1994.9939665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brigham TA, Donohoe P, Gilbert B, et al. Psychology and AIDS education: Reducing high-risk sexual behavior. Behav Soc Issues. 2002;12(1):10–18. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kearney KA, Hopkins RH, Mauss AL, Weisheit RA. Self-generated identification codes for anonymous collection of longitudinal questionnaire data. Public Opin Q. 1984;48(1B):370–378. doi: 10.1093/poq/48.1b.370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burnham C. Improving Written Instructions for Procedural Tasks. Berkeley, CA: National Center for Research in Vocational Education; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Newman AA. Pigs with cell phones, but no condoms. NY Times. 2007. [Accessed December 30, 2011]. Available from: http://www.nytimes.com/2007/06/18/business/media/18adcol.html.

- 20.Yoga-ball exercises. [Accessed December 31, 2011]. Available from: http://www.about.com.