Abstract

Individuals differ in their adjustment to stressful life events, with some exhibiting impaired functioning, including depression, while others exhibit impressive resilience. The present study examined the hypothesis that the ability to deploy a particularly adaptive type of emotion regulation—cognitive reappraisal—may be a protective factor. It expands upon existing research in three ways. First, participants’ ability to use reappraisal (cognitive reappraisal ability: CRA) was measured by using a behavioral challenge that assessed changes in experiential and physiological domains, rather than questionnaires. Second, all participants had been exposed to one or more recent stressful life events, a context in which emotion regulation may be particularly important. Third, a community sample of 78 women aged 20 to 60 was recruited, as opposed to undergraduates. Results indicate that, at low levels of stress, participants’ CRA was not associated with depressive symptoms. However, at high levels of stress, women with high CRA exhibited less depressive symptoms than those with low CRA, suggesting that CRA may be an important moderator of the link between stress and depressive symptoms.

Keywords: stress, depression, emotion regulation ability, psychophysiology

Exposure to stressful life events (SLEs) is associated with a wide variety of negative psychological and physical outcomes (Feldman, Bensing, & deRuijter, 2007; Koh, Choe, Song, & Lee, 2006; Tsoory, Cohen, & Richter-Levin, 2007). Increased depressive symptoms and elevated incidence of major depressive disorder are among the most prevalent and disabling of these outcomes (Gotlib & Hammen, 2002; Hammen, 2005; Hammen, Davila, Brown, Ellicott, & Gitlin, 1992; Monroe & Hadjiyannakis, 2002; Tennant, 2002). However, there is also remarkable variability in adjustment to stress, and many individuals do not experience increases in depressive symptoms. In fact, previous studies have found that the majority of people are resilient and experience no negative long-term outcomes (Bonanno, 2004; Freitas & Downey, 1998; Ong, Bergeman, Bisconti, & Wallace, 2006). Identifying specific vulnerability and protective factors explaining these individual differences is an important area of research. Several factors have already been identified, including neurobiological (e.g., serotonergic function, HPA axis function), genetic (e.g., polymorphisms of the 5-HT transporter gene), cognitive (e.g., attributional style), and psychosocial factors (e.g., social support, coping style) (Lau & Eley, 2008; Morris, Ciesla, & Garber, 2008; Southwick, Vythilingam, & Charney, 2005).

Additionally, recent findings have emphasized the importance of emotion regulation in adjustment to stress (Bonanno, Papa, Lalande, Westphal, & Coifman, 2004; Moore, Zoellner, & Mollenholt, 2008). Indeed, according to Gross & Muñoz (1995), emotion regulation is crucially involved in depression. Thus, the ability to use adaptive emotion regulation strategies may be an important protective factor against increases in depressive symptomatology.

Cognitive Reappraisal

Emotion regulation involves the use of behavioral and cognitive strategies to change the duration and intensity of an emotion (Gross & Thompson, 2007). Emotion regulation seems to be involved in well-being (Gross & John, 2003), adjustment to stress (Garnefski, Kraaij, & Spinhoven, 2001), and the development of depression (Gross & Muñoz, 1995; Rottenberg & Gross, 2007). Because there are many different strategies that individuals use to regulate their emotions (Parkinson & Totterdell, 1999), it is important to understand which emotion regulation strategies constitute effective emotion regulation. Appraisal theories of emotion suggest that it is an individual’s subjective appraisal of an event—that is, its meaning and significance—rather than the event itself that leads to a specific emotional reaction (Lazarus & 1984; Ortony, Clore, & Collins, 1988; Scherer, 1988). Indeed, research on appraisals and stress has found that people respond quite differently to the same (or similar) SLEs depending on their appraisals of the event (Folkman & Lazarus, 1985; Scherer & Ceschi, 1997; Smith & Ellsworth, 1987). Furthermore, learning to change the appraisals one makes in emotional situations is thought to be a key ingredient of many psychological interventions, such as cognitive (Beck, 1983) and cognitive–behavioral therapy (CBT; Gross & Muñoz, 1995; Samoilov & Goldfried, 2000). Because appraisals appear to play an important role in the generation of emotional states, emotion regulation strategies that target appraisals should be particularly effective.

A strategy known as cognitive reappraisal—reframing an event in order to change one’s emotional response to it (Gross, 1998)—directly targets appraisals. In a laboratory study of emotion regulation, Gross (1998) found that participants instructed to use reappraisal reported less negative emotion after watching an emotional film clip compared to those who were instructed to use a different emotion regulation strategy and those in the “just watch” condition. Similar laboratory studies have found the same pattern of results (Dandoy & Goldstein, 1990; Jackson, Malmstadt, Larson, & Davidson, 2000; Lazarus, Opton, Nomikos, & Rankin, 1965). Subsequent research using self-report trait measures of reappraisal has found that people who report frequently using reappraisal experience less negative emotion in emotion-eliciting situations and exhibit positive outcomes over time (Gross & John, 2003, John & Gross, 2004; Mauss, Cook, Cheng, & Gross, 2007). These studies highlight the benefits of cognitive reappraisal use and raise the question of whether this strategy might also be useful in the context of high stress. Specifically, cognitive reappraisal may serve as an important protective factor against depression by providing an effective way to down-regulate negative emotions in the context of high stress.

Cognitive Reappraisal, Coping With Stress, and Depressive Symptoms

Studies in the coping literature have more directly examined the relationships between cognitive reappraisal and mental health. For instance, Garnefski and colleagues have found a robust negative relationship between self-reported use of cognitive reappraisal and depressive symptoms in both cross-sectional and longitudinal studies of adolescents and adults (Garnefski & Kraaij, 2006; Garnefski, Kraaij, & Spinhoven, 2001; Kraaij, Pruymboom, & Garnefski, 2002).

To better understand the effects of cognitive reappraisal in the context of high life stress, a recent meta-analysis demonstrated that self-reported positive reappraisal (using cognitive reappraisal to frame a situation in a more positive way) is consistently associated with better outcomes in patients with HIV (Moskowitz, Hult, Bussolari, & Acree, 2009). Similarly, Pakenham (2005) examined a sample of caregivers for patients with multiple sclerosis. Results indicated that self-reported use of positive reappraisal had a buffering effect on the relationship between stress and negative outcomes, including depression. Carrico and colleagues extended these findings by conducting a longitudinal, experimental intervention in highly stressed males with HIV. They examined the effects of a cognitive–behavioral stress management intervention on depression (Carrico, Antoni, Weaver, Lechner, & Schneiderman, 2005). Over the 10-week treatment period, the men who received the intervention increased their use of positive reappraisal, which was in turn associated with decreases in depressive symptoms. Overall, these studies suggest that the use of cognitive reappraisal is negatively associated with depressive symptoms in the context of high life stress.

Taken together, theoretical considerations and the empirical evidence converge on a model in which individual differences in the use of cognitive reappraisal may act as an important moderator of the relationship between stress and depression. This model holds promise for furthering our understanding of the risk factors that contribute to depression, as well as for guiding the development of prevention and intervention programs for at-risk populations.

Limitations of Previous Research

Unfortunately, however, there are three important limitations in the existing research that make it difficult to comfortably conclude that CRA acts as a buffer against depressive symptoms in the face of life stress. First, nearly every study examining individual differences in cognitive reappraisal has used self-report measures of trait cognitive reappraisal use. This limits existing research because (a) self-report measures can be subject to biases (Feldman Barrett, 1997; Wilhelm & Grossman, in press), and (b) self-reported reappraisal use may be crucially different from the ability to use cognitive reappraisal effectively. In other words, when reporting on reappraisal use, participants may be referring to frequency of emotion regulation attempts which may be independent or even inversely related to the efficacy of these attempts.

Second, very little of the existing research on cognitive reappraisal has examined it in the context of stress and depression. For example, many studies have only examined the main effect of cognitive reappraisal on depressive symptoms (Garnefski & Kraaij, 2006; Kraaij, Pruymboom, & Garnefski, 2002). In addition, the small amount of research that has examined cognitive reappraisal in the context of high stress (e.g., Carrico et al., 2005; Pakenham, 2005) has used samples that have all experienced the same types and amounts of stress. While these findings are very important, the potential moderating effects of cognitive reappraisal on depressive symptoms across a range of stressful contexts remain largely untested. Specifically, it may be that the use of cognitive reappraisal is of relatively greater importance under higher stress (as compared to lower stress) contexts. This could be the case because, under high stress contexts, there are more negative emotions that need to be regulated—if they are not, these emotions could potentially spiral out of control and lead to negative emotional outcomes such as depression. In a lower stress context, however, the use of reappraisal may be less predictive of depression because there are simply less negative emotions to regulate. In order to test this hypothesis, however, samples containing a wide range of stress levels (from low to high) and a wide variety of stressor types is needed.

Third, there has been an overreliance on undergraduate samples (Gross, 1998; Gross & John, 2003; Mauss et al., 2007). It is unclear whether the results found in these samples generalize to other age groups and to individuals from diverse socioeconomic backgrounds. The ability to use cognitive reappraisal (CRA), which could be particularly important in the context of high stress, then, has not been examined as a predictor of depressive symptoms.

The Present Research

To examine whether CRA might be a protective factor in the context of high life stress, we measured cumulative life stress, CRA, and current depressive symptoms. To measure CRA while avoiding the pitfalls associated with sole reliance on retrospective questionnaires of emotion, we implemented a multimethod laboratory paradigm. In this paradigm, participants were instructed to use reappraisal while they watched a sad film clip. CRA was indexed by changes in self-reported sadness experience and skin conductance level during the “reappraised” clip as compared to a sad film clip that participants simply watched. We focus on changes in sadness because the down-regulation of this emotion may be of particular importance in protecting against depression (Joormann, Siemer, & Gotlib, 2007). By using a physiological measure in addition to self-reports of sadness, we aimed at providing an independent marker of CRA that is less prone to self-report biases. We focus specifically on skin conductance because past research has found that self-reported sadness is associated with skin conductance level (Mauss, Levenson, McCarter, Wilhelm, & Gross, 2005; Kreibig, Wilhelm, Roth, & Gross, 2007).

The construct of CRA is new, and therefore largely unexplored. For this reason, it is important to compare our measure’s predictive validity to that of existing measures of trait cognitive reappraisal, as well as to address potential key confounds such as emotional reactivity. By measuring these constructs, we are able to answer two important questions in addition to our hypotheses: First, how does our measure of CRA relate to other, potentially related constructs such as trait cognitive reappraisal use and affective reactivity? And, second, does CRA predict depression in the context of high stress even when controlling for potential key confounds?

To examine cognitive reappraisal ability in what may be a particularly crucial context—high stress—women in the present sample had to have experienced at least one stressful life event (SLE) in the past three months. Importantly, this recruitment strategy yielded (a) a wide range of cumulative stress levels (some individuals had experienced a relatively minor event, such as a recent move, while others had experienced a major event, such as the death of a loved one), which allowed us to examine the relative usefulness of CRA across a range of stressful contexts, from relatively low to highly stressful; and (b) a wide range of stressor types, which increases generalizability of results.

The conceptualization and measurement of stress is complex (Lazarus, DeLongis, Folkman, & Gruen, 1985; Tennant, 2002). With this in mind, we obtained a comprehensive measure of stress by (a) assessing the cumulative impact of 45 SLEs that participants could have experienced and (b) assessing these SLEs over the past 18 months. Three key considerations guided this decision. First, because the individual SLE that led women to participate in the present study was unlikely to be the only source of stress affecting current depressive symptoms, we assessed a comprehensive list of possible SLEs. Second, we measured the perceived impact of objectively defined events (e.g., loss of employment) rather than exclusively objective aspects (e.g., number of SLEs) because of convincing arguments that stress is, in essence, a subjective phenomenon. In other words, by trying to remove any kind of subjectivity from one’s measure of stress, one might be missing the most vital piece of information (Lazarus et al., 1985). Third, we measured the impact of events as far back as 18 months because previous research has shown that SLEs can have long lasting, negative impacts on people’s lives (Lorenz, Wickrama, Conger, & Elder, 2006; Morales & Guerra, 2006).

Finally, to enhance generalizability of results, we recruited a community sample of women with a wide range of ages and socioeconomic backgrounds.

Hypotheses

Our hypotheses were as follows:

Hypothesis 1: There will be a significant positive correlation between cumulative stress and depressive symptoms.

Hypothesis 2: The two indices of CRA (changes in sadness and skin conductance level) will be positively related to one another because they are thought to be measuring the same construct (ability to down-regulate negative emotion). However, because physiological and experiential components of emotional responding are often relatively independent from one another (Hodgson & Rachman, 1974; Mauss et al., 2005), we expected these two measures not to be so highly correlated as to be redundant with one another. Because we conceptualize CRA as a construct distinct from self-reported emotion regulation use, this measure should be only weakly correlated with self-report measures of cognitive reappraisal use and emotional reactivity.

Hypothesis 3: CRA will moderate the relationship between cumulative stress and current depressive symptoms such that as CRA increases, the relationship between cumulative stress and depressive symptoms will be attenuated.

Hypothesis 4: CRA will predict current depressive symptoms above and beyond self-report measures of trait cognitive reappraisal use and emotional reactivity. That is, CRA will moderate the relationship between cumulative stress and current depressive symptoms when controlling for self-reported cognitive reappraisal and reactivity.

Methods

Participants

Because of known gender differences in emotional reactivity (Timmers, Fischer, & Manstead, 1998), exposure to stress (Turner, Jay, & William, 1989), and risk for depression (Kendler, Thornton, & Gardner, 2000), and to reduce variance within the sample that may limit our ability to address the core hypotheses, only female participants were recruited.

Participants were recruited through postings in online bulletins or in public areas such as laundromats and local hospitals. To meet inclusion criteria, all women were required to have experienced an SLE within the past three months. An SLE was defined to participants during recruitment as an event with a distinct starting point within the past three months (i.e., a relatively acute instead of a chronic stressor) that had a significant, negative impact on participants’ lives. A total of 245 women responded to recruitment materials. Of these, 135 were found eligible after phone screening. Participants were ineligible because they either did not experience an SLE in the past 3 months or their SLE did not meet our criteria. Of those determined to be eligible, 82 scheduled a time to come to the laboratory. The rest of the women either were unable to find a time to come into the lab or were not interested in participating after being informed about the full study procedures. A total of 78 women completed the laboratory session. The other four could not complete the entire CRA task due to time constraints.

Of the 78 participants, 13 reported experiencing no sadness during the first sad film clip (baseline sad clip). These 13 participants were excluded from all analyses (see a priori explanation for this exclusion in the Measures section). This left 65 participants for analyses. Of these, skin conductance level (SCL) data were not available due to technical difficulties for 13 participants. This left 65 participants for analyses involving CRA-SAD (CRA quantified using changes in self-reported sadness) and 52 participants for analyses involving CRA-SCL (CRA quantified using changes in SCL).1 Sample sizes for each of our analyses are listed in Tables 1 and 2. Slight differences in sample sizes are due to differences in missing values across variables.

Table 1.

Correlations of Key Measures With Both Indices of Cognitive Reappraisal Ability (CRA)

| CRA-SADa | CRA-SCLb | |

|---|---|---|

| Variables in the regression model | ||

| Cumulative stress | −.01 | .24† |

| Current depressive symptoms | −.19 | −.01 |

| Demographics | ||

| Years of education | −.12 | −.22 |

| Family income | −.05c | −.11d |

| Age | −.04 | .25† |

| Trait cognitive reappraisal use | .12 | .21 |

| Emotional reactivity | ||

| Sadness reactivity | .14 | −.19 |

| SCL reactivity | −.23e | −.14 |

n = 60–62, except for family income and SCL reactivity.

n = 51–52, except for family income.

n = 52.

n = 42. Lower n’s are due to people who indicated that they did not know or chose not to report their family income.

n = 52 because SCL data was only available for 52 people.

p < .10.

Table 2.

Current Depressive Symptoms as Predicted by Cognitive Reappraisal Ability (CRA-SAD: Changes in Sadness and CRA-SCL: Changes in Skin Conductance Level) and Cumulative Stress

| β | t | p | Partial η2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRA-SAD | ||||

| Cumulative stress | .36 | 3.10 | .003 | .15 |

| Cognitive reappraisal ability (CRA-SAD) | −.11 | −.92 | .36 | .02 |

| Cumulative stress × CRA-SAD | −.26 | −2.17 | .03 | .08 |

| CRA-SCL | ||||

| Cumulative stress | .54 | 3.90 | .001 | .24 |

| Cognitive reappraisal ability (CRA-SCL) | −.10 | −.77 | .45 | .01 |

| Cumulative stress × CRA-SCL | −.31 | −2.34 | .02 | .10 |

Note. R2 for the CRA-SAD model = .22. R2 for the CRA-SCL model = .26. n = 61 for CRA-SAD and n = 51 for CRA-SCL.

The most common SLEs in the final sample were: sudden unemployment (36%), illness, injury, or death of a close family member or friend (19%), long distance move (14%), exposure to crime (8%), and divorce or the end of a long-term romantic relationship (6%). The ethnic composition was mixed: 72% were European American, 8% were Asian American, 6% were Hispanic American, 5% were African American, 7% were either mixed-race or other, and 2% of the sample chose not to identify their ethnicity. The average age was 34.9 years (SD = 11.8, Range: 20–62). Participants reported a wide range of family income levels: 9% reported earning less than $10,000 per year, 6% between $10,000 and $20,000, 8% between $20,000 and $30,000, 9% between $30,000 and $40,000, 12% between $40,000 and $50,000, 42% made more than $50,000, and 14% did not report their income. A wide range of educational backgrounds was also reported (ranging from partial completion of high school to graduate degree).

Procedure

Upon arrival at the lab, participants were greeted by a trained research assistant, and explained the study procedures. To maximize privacy during data collection, the participant was left alone in the experiment room while the research assistant stayed in an adjacent room that was connected via intercom. To maximize comfort and to ensure the same laboratory environment for each participant, the room was quiet and windowless. The study began by participants filling out questionnaires, including questionnaires assessing trait emotion regulation, exposure to SLEs, and current depressive symptoms (see Measures section). Other self-report measures were also collected that are not reported on here. The questionnaire portion of this session took approximately one and a half hours. All questionnaires were filled out on a computer.

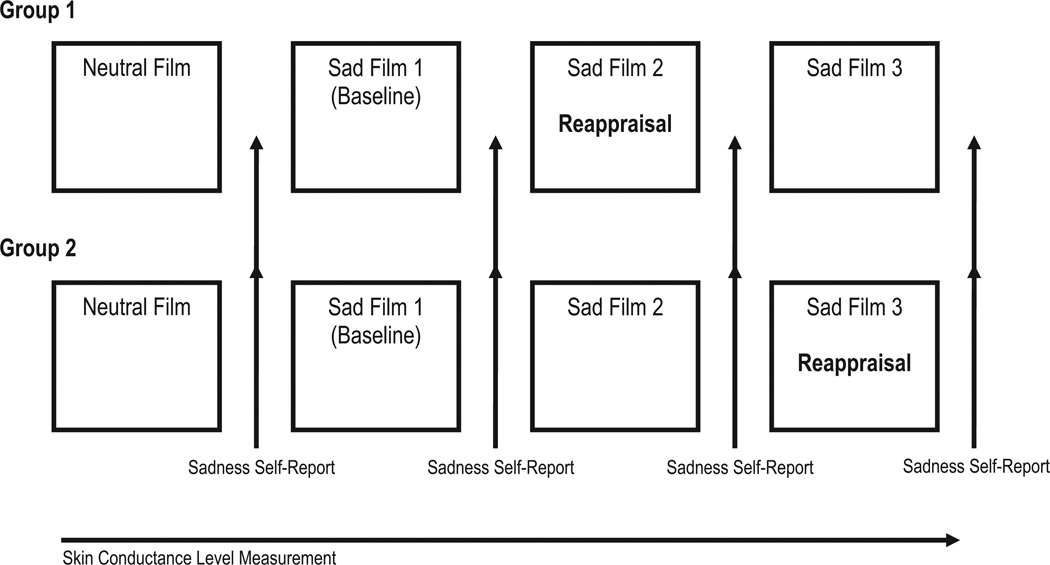

The laboratory CRA task was administered at the end of the laboratory session (see Figure 1). Participants remained seated alone in the lab room. To measure skin conductance level during the task, the experimenter connected sensors to participants’ fingers. To induce a relatively comparable, neutral mood across participants at the beginning of this task, a 3-min emotionally neutral video clip depicting nature scenes was presented. Similar films have been used successfully in the past (Hagemann et al., 1999; Kreibig et al., 2007). Once the clip ended, participants rated the greatest amount of sadness (in addition to 12 distracter emotions) that they experienced during the clip. Next, participants were presented with three film clips pretested to induce moderate amounts of sadness. Film clips have been widely used in previous research to induce sadness (Fredrickson & Levenson, 1998; Rottenberg, Ray, & Gross, 2007) and are considered more ecologically valid than still pictures or words (Rottenberg et al., 2007). In addition, because film clips are standardized, they eliminate confounds associated with recall procedures. Each of these film clips was approximately two minutes long, depicted two people discussing an emotional event, and had received similar normative ratings of sadness during pretesting. These film clips were chosen to induce only moderate (instead of extreme) levels of sadness for two reasons. First, based on the types of emotional situations that individuals encounter on a frequent basis, films that elicit moderate amounts of sadness were thought to be more ecologically valid. Second, by inducing moderate amounts of sadness, we aimed to minimize ceiling or floor effects in participants’ experience of sadness across different conditions, thus increasing the variability in self-reported sadness, and in turn, their CRA scores.

Figure 1.

Schematic of experimental procedures for measuring cognitive reappraisal ability (CRA).

During two of the sad film clips, participants were simply asked to “watch the following film clip carefully.” During one of the sad film clips, participants were asked to reappraise the situation they were watching in order to decrease its emotional impact. The full reappraisal instructions are provided in the Appendix. After this, participants were encouraged to ask questions to ensure that they understood what was being asked of them. These instructions were based on writing techniques used in clinical research to encourage patients to reframe a stressful event in a more positive way (Lange, van de Ven, & Schrieken, 2003; Pennebaker & Chung, 2007).

After each film clip, participants reported the greatest amount of sadness (in addition to 12 distracter emotions) that they experienced during the clip. To avoid confounding reappraisal effects with habituation to the sad film clips or regression to the mean, participants were randomly assigned to two groups in a within-individual repeated measures design. The order of the film clips was the same for both groups, but the order of reappraisal instructions differed for the two groups (see Figure 1; Group 1 used reappraisal during the second sad film, Group 2 used reappraisal during the third sad film). On all remaining films, participants were instructed to just watch the film clip. Because neither group is reappraising during the first sad film clip, sadness ratings during this film were used as a sadness baseline.

After watching the film during which they were instructed to use reappraisal, participants were also asked to answer the following question: “How hard did you try to think about the situation in a positive way?” This question served as a manipulation check and measure of cognitive reappraisal effort.

On average, the cognitive reappraisal task lasted about 30 minutes, and the entire laboratory session lasted approximately 2.5 hours. After completing the session, participants were debriefed and compensated $35 for their time.

Measures

Cumulative stress

The cumulative negative impact of SLEs that each participant had experienced in the past 18 months was measured with the Life Experiences Survey (LES; Sarason, Johnson, & Siegel, 1978), a widely used measure of stress (e.g., Herrington, Matheny, Curlette, McCarthy, & Penick, 2005; Roth, Goode, Williams, & Faught, 1994; Schmidt, Demulder, & Denham, 2002).

The LES consists of 45 items assessing a wide range of potentially stressful events. For each item, participants indicated if a particular event had occurred within the previous 18 months, and the impact of each event they experienced with ratings on a 7-point scale, where −3 indicates “extremely negative,” 0 indicates “no impact,” and +3 indicates “extremely positive.” Although the LES provides both the positive and negative impact of stressors, negative events are better predictors of negative psychological outcomes (Sarason, Sarason, Potter, & Antoni, 1985; Vinokur & Selzer, 1975). Therefore, like others (Denisoff & Endler, 2000; Herrington et al., 2005) we used the negative impact of SLEs as our measure of interest. Lastly, because we hypothesized that our results should hold across a wide range of stressors, we summed impact ratings across all types of stressors in the LES. Thus, a total cumulative negative impact score was calculated by summing all impact ratings of negatively rated SLEs. Summed scores were then reverse coded, so that a higher score denotes more cumulative stress. We refer to this variable as “cumulative stress” for the remainder of this article. The present sample included individuals who had experienced a wide range of cumulative stress (M = 15.9, SD = 11.5, Range: 2–60; number of negative events: M = 7.9, SD = 4.5, Range: 1–24). For comparison, the mean level of 12-month cumulative stress in a normative sample of young adult women was 8.3 (Denisoff & Endler, 2000). In the current sample, 22% of participants had a score of 8 or less. Thus, even though everyone in the sample had experienced a recent SLE, a sizable proportion of our sample had cumulative stress levels that were low compared to a normative sample.

Current depressive symptoms

Current depressive symptoms were measured using the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI; Beck & Steer, 1984), a self-report measure consisting of 21 items. One question, which pertains to suicidal thoughts, was not included due to IRB concerns. The BDI has been shown to have adequate internal consistency (Beck & Steer, 1984; alpha = 0.88 in the current sample) and has been widely used to measure current depressive symptoms (e.g., Brands et al., 2007; O’Donnell, Wardle, Dantzer, & Steptoe, 2006; Pearlstein, Zlotnick, Battle, Stuart, O’Hara, & Price, 2006). Because the sample in this study was on average stressed, average BDI scores were elevated (M = 13.7, SD = 8.9). The distribution of scores within the categories described by Beck and colleagues (Beck, Steer, & Garbin, 1988) are as follows: 0–9 (n = 29, indicating minimal depression), 10–18 (n = 17, indicating mild-moderate depression), 19–29 (n = 16, indicating moderate-severe depression), and 30–63 (n = 3, indicating severe depression).

Self-reported trait cognitive reappraisal

Trait cognitive reappraisal use was assessed with the Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (ERQ). The ERQ is a widely used 10-item self-report questionnaire, six of which measure reappraisal (Gross & John, 2003). Answers are given on a seven-point Likert scale, with one meaning “strongly disagree” and seven meaning “strongly agree.” The internal reliability was high (alpha = .88).

Cognitive reappraisal ability

Cognitive reappraisal ability, or the amount that individuals are able to decrease their level of sadness when instructed to use cognitive reappraisal, was measured with a laboratory paradigm using self-reported sadness and SCL (full description in Procedure section).

Self-reported sadness was measured immediately after each film clip (as shown in Figure 1). Participants rated, on a nine-point Likert scale, the greatest amount of 13 different emotions that were experienced during the film that was just watched, with 1 indicating “not at all,” and nine indicating “extremely.” Although sadness is of primary interest, the list also contained 12 distracter items to prevent participants from guessing that we are primarily interested in changes in sadness. Because the reappraised film was not the same for all participants (see Figure 1), sadness ratings were z-scored for each film clip so that CRA scores could be compared across individuals in different experimental groups. Change scores were calculated by subtracting sadness ratings given after the reappraised film clip from sadness ratings given after the baseline sad film. Thus a greater score indicates greater CRA. This variable is referred to as CRA-SAD. Mean scores on CRA-SAD were 0.39 (SD = 0.84).

We decided a priori that participants who reported experiencing no sadness during the baseline sad clip would be excluded from all analyses. This decision was made because the CRA scores for these individuals are difficult to interpret—many of these individuals would have a zero or negative change score (indicating poor CRA) simply because the baseline sadness induction failed, and not because they were truly low in CRA. Thirteen individuals were excluded from analyses for this reason.2

Skin conductance level (SCL) is a measure of sympathetic activation. It was measured using a constant-voltage device that passed 0.5 V between Beckman electrodes (using an electrolyte of sodium chloride in Unibase) attached to the palmar surface of the middle phalanges of the first and second fingers of the nondominant hand. During the experimental session, SCL was sampled continuously at 1000 Hz using a BIOPAC data recording. Afterward, customized analysis software (Wilhelm, Grossman, & Roth, 1999) was applied to data reduction, artifact control, and computation of average SCL scores for each participant for each film clip.

Previous research has found that increases in sadness are associated with decreases in SCL (Kunzmann & Gruhn, 2005; Mauss et al., 2005; Kreibig et al., 2007). Based on these findings, we defined greater CRA-SCL as relatively greater change scores between the reappraisal and sadness baseline film clips. Change scores were calculated by first converting mean SCL to z-scores, and then subtracting SCL during the baseline sad film clip from SCL during the reappraised film clip. In this way, more positive scores (lesser decrease in SCL) denote greater CRA. Mean scores on CRA-SCL were 0.04 (SD = 0.14).

Possible group effects were examined to make sure that there were no significant differences between experimental groups on either measure of CRA. T tests revealed that CRA did not differ significantly between experimental groups using either index of CRA, CRA-SAD: t(60) = .57, p = .57, or CRA-SCL: t(50) = −.44, p = .66.

Emotional reactivity

The CRA task, as described above, was also used to measure emotional reactivity by quantifying changes in sadness from the neutral film clip to the sadness baseline clip. It was important to measure emotional reactivity separately from our measure of CRA in order to ensure that the measure of CRA was not confounded with participants’ reactivity to the sad films. To parallel the two indices of CRA, we calculated two indices of reactivity: changes in sadness and SCL. For sadness reactivity, sadness ratings on the neutral film clip were subtracted from sadness ratings on the baseline sad clip (M = 4.05, SD = 2.46). For SCL reactivity, SCL during the baseline sad clip was subtracted from SCL during the neutral clip (M = −.02, SD = .24). In both cases, the larger the score, the larger the emotional reactivity from the neutral to the baseline sad clip.

Results

Manipulation Check: Sadness Induction

To confirm that the three sad film clips induced moderate amounts of sadness in the present sample, we examined mean sadness ratings for each film clip for unmanipulated (uninstructed) film viewings (the whole sample for the first sad film, Group 2 for the second sad film, and Group 1 for the third sad film). The mean (SD) sadness ratings were 5.97 (2.14; Film 1), 6.48 (1.98; Film 2), and 6.90 (2.10; Film 3). All three of the sad film clips induced significantly greater reports of self-reported sadness than the neutral film clip (M = 1.92, SD = 1.68; all ps < .01). In addition, each of the three sad film clips induced significantly greater levels of self-reported sadness than fear, anger, and happiness (all ps < .01).

Manipulation Check: Cognitive Reappraisal Instruction

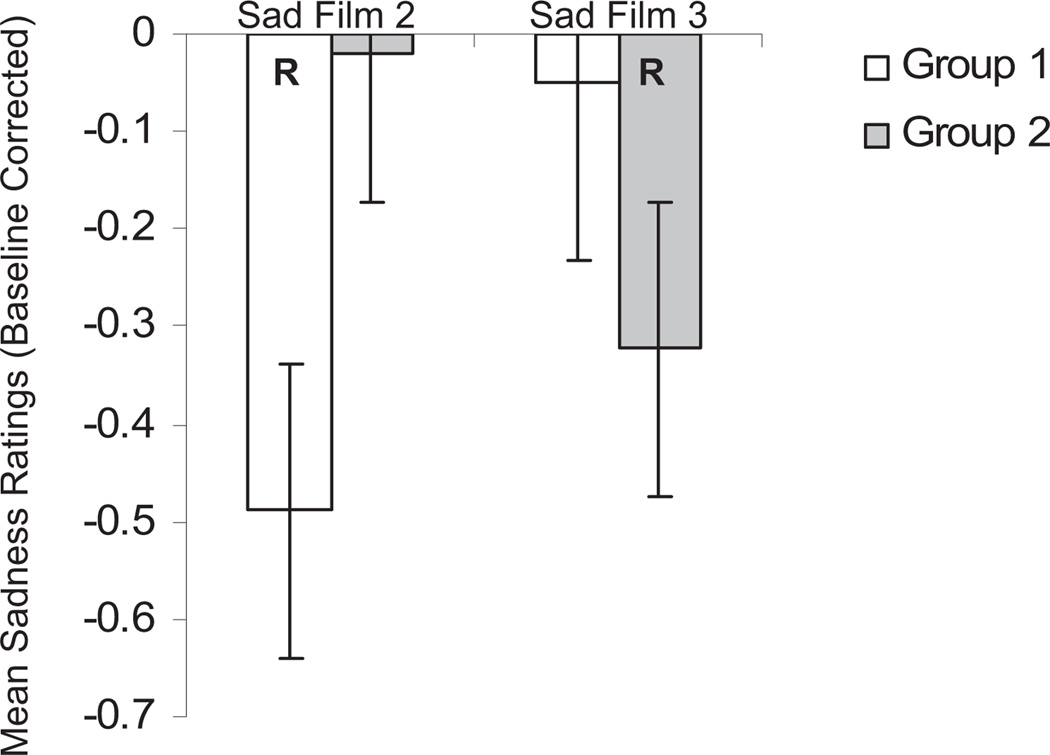

To test whether the reappraisal instructions affected sadness reports consistent with instructions, we conducted a repeated measures ANOVA with film (Sad Film 2 vs. 3) as a within-individual factor and experimental group (reappraisal instruction vs. no instruction) as a between subjects factor. To take into account each individual’s sadness baseline, we entered change scores from the sad baseline to Sad Films 2 and 3, respectively. These scores are in z-units, and a negative score indicates that the individual reported less sadness on the film in question than on the baseline sad film. As illustrated in Figure 2, the interaction between film clip and experimental group was significant, F(1, 60) = 7.80, p < .01. The differences observed between groups were in the expected directions based on the cognitive reappraisal instructions (see Figure 1): during the second sad film, Group 1 reported greater decreases in sadness ratings relative to Group 2, t(61) = −2.21, p = .03. During the third sad film clip, when Group 2 was asked to use cognitive reappraisal and Group 1 was just watching, Group 2’s mean sadness ratings decreased to a greater degree than Group 1’s. This group difference, however, was not statistically significant, t(61) = 1.06, p = .29. Although not all of the predicted group differences were significant, the direction of changes in means on this task suggest that participants were attempting to use cognitive reappraisal and at least some were succeeding in their attempts. Additionally, it may not be surprising that the group difference on the third sad film was not significant, given that Group 1 had been asked to reappraise on an earlier film. This group might have persevered using cognitive reappraisal during the last film clip, resulting in lower sadness ratings than would have otherwise been observed. Note that Group 1 ratings on the third sad film were used only for the manipulation check described above, and not for testing our hypotheses. For this reason, the lack of group differences on the third film does not limit the validity of the CRA measure.

Figure 2.

Sadness ratings (change from baseline sad film clip) during the cognitive reappraisal task for each experimental group. The Y-axis represents the z-scored sadness ratings during either Sad Film 2 or Sad Film 3, minus z-scored sadness ratings during the baseline sad film (Film 1). Thus, more negative scores mean greater decrease in self-reported sadness relative to the baseline sad film. R’s indicate which experimental group was instructed to use cognitive reappraisal during each film clip.

Lastly, participants reported having tried hard to follow the instructions during the reappraisal film (M of effort ratings = 7.0, SD = 1.7). This suggests that, on average, participants tried to use cognitive reappraisal when instructed, but might have achieved varying levels of success.

Hypothesis One: Cumulative Stress and Depressive Symptoms

As expected, there was a significant positive relationship between cumulative stress and current depressive symptoms (r = .36, p < .01).

Hypothesis Two: Discriminant Validity of Cognitive Reappraisal Ability

The two indices of CRA were positively but only marginally related to one another (r = .24, p = .08). Because the two indices do not appear to be redundant with one another, we conducted separate analyses for them.

Correlations between CRA-SAD, CRA-SCL, and measures of cumulative stress, depressive symptoms, demographics, trait cognitive reappraisal use, and emotional reactivity are shown in Table 1. As indicated in Table 1, Column 1, CRA-SAD was not significantly related to cumulative stress, depressive symptoms, the demographic variables, trait cognitive reappraisal use, and emotional reactivity (all ps > .10). For CRA-SCL (Table 1, Column 2), similar relationships were found. As with CRA-SAD, CRA-SCL was not significantly related to cumulative stress, current depressive symptoms, demographic variables, trait cognitive reappraisal use, and emotional reactivity (all ps > .10, except for cumulative stress and age where ps = .08).

Hypothesis Three: Does Cognitive Reappraisal Ability Moderate the Relationship Between Cumulative Stress and Depressive Symptoms?

To test the hypothesis that CRA acts as a moderator of the relationship between cumulative stress and depressive symptoms, a series of linear regressions was conducted. Depressive symptoms were entered as the dependent variable, and cumulative stress, CRA, and the interaction of the two were entered as the independent variables (all independent variables were centered). Because both measures of CRA were uncorrelated with cumulative stress (see Table 1), multicollinearity between the independent variables was low (in both models, tolerance > .3, and VIF < 3.5).

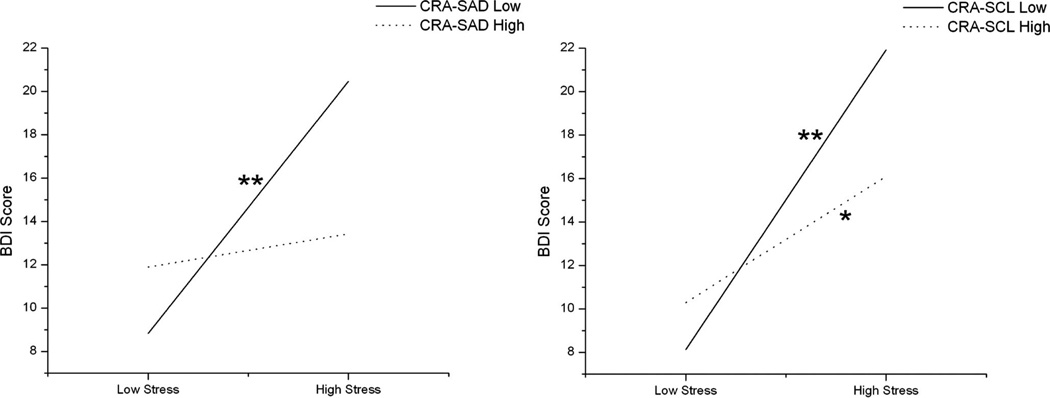

The results of these regressions are shown in Table 2. For CRA-SAD, there was a positive main effect of cumulative stress, and a significant interaction between CRA-SAD and cumulative stress in predicting depressive symptoms. There was no significant main effect of CRA-SAD. For the addition of the interaction term to the model, the change in R2 was significant, R2 change = .07, F(1,57) = 4.7, p = .03. To examine the interaction, the relationship was plotted using values ± 1 standard deviation on CRA-SAD and cumulative stress, based on the procedures outlined by Aiken and West (1991). Simple slopes analyses revealed that the slope of the regression line for high CRA-SAD was not significantly different from zero, β = .09, t(59) = .49, p = .62, while the slope of the regression line for low CRA-SAD was significantly greater than zero, β = .64, t(59) = 3.63, p < .001. In other words, as illustrated in Figure 3, Panel A, participants high in CRA-SAD did not differ in depressive symptoms depending on their cumulative stress level, whereas those low in CRA-SAD differed in depressive symptoms depending on their level of stress. We next examined the same interaction effect, but with high versus low cumulative stress on separate regression lines at high versus low levels of CRA-SAD. This analysis revealed that the slope of the regression line across different levels of CRA-SAD was not significantly different from zero at low stress, β = .17, t(59) = .89, p = .38. At high stress, however, the slope of the regression line was significantly lower than zero, β = −.39, t(59) = −2.47, p = .02, suggesting that, at high levels of stress, participants with high CRA-SAD had lower levels of depressive symptoms than those with low CRA-SAD.

Figure 3.

The interaction of cumulative stress and cognitive reappraisal ability (CRA) on current depressive symptoms (BDI = Scores on the Beck Depression Inventory). Panel A uses CRA-SAD (changes in sadness) as the index of CRA, while Panel B uses CRA-SCL (changes in skin conductance level). Values depict estimates at ± 1 SD for cumulative stress and CRA. Asterisks denote slopes that are significantly different than zero (* p < .05. ** p < .01.).

Similar results were obtained with regression analyses using CRA-SCL. As shown in Table 2, there was a significant main effect of cumulative stress, as well as a significant interaction between CRA-SCL and stress. The main effect of CRA-SCL was not significant. For the addition of the interaction term to the model, the change in R2 was significant, R2 change = .09, F(1, 46) = 5.5, p = .02. As illustrated in Figure 3, Panel B, this interaction revealed a similar pattern to that found using CRA-SAD. Simple slopes analyses revealed that both of the regression lines’ slopes were significantly greater than zero: for high CRA-SCL, β = .31, t(49) = 2.30, p = .03, and for low CRA-SCL, β = .76, t(49) = 3.96, p < .001. The strength of this positive relationship was greater for those with low CRA-SCL, as indicated by the significant interaction. We next examined the same interaction effect, but with high versus low cumulative stress on separate regression lines at high versus low levels of CRA-SCL. Simple slopes analysis revealed that at low levels of stress, the slope of the regression line was not significantly different from zero, β = .12, t(49) = .74, p = .46. At high levels of stress, however, the slope was negative and significantly less than zero, β = −.32, t(49) = −2.00, p = .05, suggesting that, at high levels of stress, participants with high CRA-SCL had lower levels of depressive symptoms than those with low CRA-SCL.

Hypothesis Four: Controlling for Potential Confounds

Although potential key confounds (trait cognitive reappraisal and emotional reactivity) were not significantly correlated with either index of CRA, we wanted to confirm that the interactions described above would predict depressive symptoms above and beyond these measures. We entered trait cognitive reappraisal and sadness reactivity as additional predictors to the CRA-SAD model described above. We also added trait cognitive reappraisal and SCL reactivity as additional predictors to the CRA-SCL model described above. In each case, the interaction between CRA and cumulative stress remained significant (all ps < .05).3

Discussion

On average, stress leads to increases in a wide range of negative psychological outcomes, including depression. Our study, however, focused on the observation that some people, even under very stressful circumstances, do not experience elevated depressive symptoms. Because stressful life events (SLEs) are often inherently emotional, we argued that the ability to effectively regulate negative emotions could be an important contributor to individual variation in adjustment to stress. Cognitive reappraisal is a promising type of emotion regulation because it is a particularly effective strategy for down-regulating negative emotion. For this reason, the ability to use reappraisal may serve as an important protective factor in the context of stress. The current study tested the hypothesis that cognitive reappraisal ability (CRA) would act as a moderator of the relationship between cumulative stress and depressive symptoms.

The present study first replicated the frequently reported positive relationship between cumulative stress and depressive symptoms in a community sample of women. Second, we found that CRA, as measured in a multimethod laboratory procedure involving a real-time behavioral challenge, shows high discriminant validity with respect to potential key confounds such as trait cognitive reappraisal use and emotional reactivity (sadness and SCL reactivity). Third, we found support for the hypothesized interaction between CRA and cumulative stress in predicting depressive symptoms. Specifically, at higher levels of cumulative stress, women with high CRA exhibited less depressive symptoms than those with low CRA. At lower levels of cumulative stress, CRA was not associated with depressive symptoms. These interactions remained significant when controlling for trait cognitive reappraisal use and emotional reactivity, demonstrating the incremental validity of the CRA construct.

Implications for Understanding Individual Variation in Adjustment to Stress

The present results support a model in which individual differences in CRA act as a moderator of the link between stress and depression. This model has three important implications: First, in line with previous research, resilience under stressful circumstances is possible (Bonanno, 2004, 2005; Ong et al., 2006). Second, the ability to effectively regulate emotions, in addition to self-reported emotion regulation use, appears to be critically implicated in adjustment to stress (Bonanno et al., 2004;Troy & Mauss, in press). Third, the ability to use one specific regulatory strategy, cognitive reappraisal, may be particularly effective for managing one’s negative emotions in the context of stress. The fact that the observed results were obtained across a wide range of stressor types is consistent with the notion that CRA is a tool that can be deployed across a wide range of situations.

Some may find it surprising that CRA was not related to cumulative stress, for three reasons. First, this finding is at odds with models that suggest that emotion regulation could act as a mediator rather than a moderator in the relationship between stress and depression (McCarthy, Lambert, & Moller, 2006). Clearly, some types of stress might directly impact some types of emotion regulation. However, our results are more consistent with a model in which CRA acts as a moderator of the link between stress and depression. Future studies are needed to better understand when which type of model—mediation versus moderation—applies to which type of emotion regulation.

In addition, it might seem surprising that people high in CRA would not automatically change their appraisals of negative life events. In other words, one might expect a negative relationship between CRA and cumulative stress. However, we argue, and the present data support, that CRA and ratings of cumulative stress are the result of two different types of appraisal processes. CRA relies on the ability to reassess the emotional impact of a situation when needed, whereas ratings of cumulative stress measure all appraisals (both emotional and nonemotional) of a stressor. In this way, individuals who are high in CRA could perceive a stressor as an extremely negative event in terms of disrupting their lives, but could still decrease their negative emotions in response to this event.

A third reason for why the lack of correlation between CRA and cumulative stress may seem surprising is that one might expect individuals high in CRA to generate less stressors in their lives, which would lead to an overall decrease in the amount of stress experienced. While overall our data did not support this hypothesis, it may be that for some types of stressors—those dependent on the person—this hypothesis might hold. Because our current measure of cumulative stress collapses across all stressor types, we are unable to test this hypothesis. It will be important for future studies to better measure and address the question of stressor types to gain a better understanding of when—if at all—CRA relates to life stress.

Implications for Understanding Emotion Regulation

The present results advance our understanding of what constitutes successful reappraisal in three ways. First, ability to use reappraisal and trait reappraisal use appear to be distinct constructs. In line with this idea, our measure of CRA displayed high discriminant validity: neither of the indices of CRA (CRA-SAD and CRA-SCL) was related to a self-report measure of cognitive reappraisal use. We also found that both indices of CRA went above and beyond trait cognitive reappraisal use in predicting depressive symptoms in the context of stress.

One possible explanation for the lack of correlation between self-reported reappraisal and CRA could be that self-reports of reappraisal use measure several different aspects of reappraisal, including frequency of use, motivation to use, and ability to use. In this way, self-reports of reappraisal may be collapsing several different aspects of reappraisal into one measure. Because previous research has found a reliable relationship between self-reported reappraisal and outcomes, these are clearly useful measures. However, it may be that separating these different aspects of reappraisal (e.g., motivation, ability) provides an even better understanding of how reappraisal relates to depression. The current study provides an important first step by specifically examining ability. In addition, an online behavioral test of reappraisal may capture reappraisal ability rather directly, while retrospective questionnaires on reappraisal may be influenced to a greater degree by factors such as salience of events, social desirability, and idealized self-concepts (for a review, see Wilhelm & Grossman, in press).

A second implication of our results is that CRA and reappraisal use may be associated with outcomes via different mechanisms. Recall that we did not find a main effect of CRA on depressive symptoms. In contrast, previous research has found direct relationships between self-reported cognitive reappraisal use and mental health (Garnefski & Kraaij, 2006; Garnefski et al., 2001). Indeed, in the current study, trait cognitive reappraisal use was negatively associated with depressive symptoms (r = −.40, p < .01). Why would CRA be related to depressive symptoms only in the context of high stress while self-reported reappraisal use is related to mental health across stress levels? One answer to this question might be that reappraisal ability and use relate to depressive symptoms in different ways. Perhaps ability is particularly important in highly stressful situations because this is the context in which it becomes necessary to be able to actually change one’s emotional states—without effective emotion regulation, a negative emotional response to stress could spiral out of control and lead to increases in depression. The use of reappraisal (regardless of success), on the other hand, may be associated with depression across stressful contexts because it measures individuals’ enhanced motivation to use reappraisal, which may have positive effects in both high and low stress contexts.

A third aspect of the present results with important implications for our understanding of what constitutes successful emotion regulation is that the two indices of CRA (CRA-SAD and CRA-SCL) were only marginally positively correlated with one another. While positive, this relationship was smaller than what a unitary CRA construct would lead one to expect. Thus, it appears that CRA-SAD and CRA-SCL measure two somewhat distinct processes. One could argue that perhaps CRA-SAD is simply a measure of experimental demand. In this case, however, this construct should not predict positive outcomes in the context of stress. Similarly, one could argue that CRA-SCL is simply an index of effort expended during the task. However, we again would not predict that this construct would be associated with depressive symptoms. Another possibility, and the one that we prefer, is that these two indices measure different, albeit related targets of the regulatory process: subjective experience and physiology. Previous research (i.e., Mauss et al., 2005) has found that subjective experience and physiological responses are loosely coupled components of emotional responding. With this in mind, it may not be surprising that the regulation of these components is also loosely coupled. In addition, previous studies have found individual differences in which aspects of emotion are most attended to. For example, Feldman Barrett (Barrett, 1998; Feldman Barrett, 1995) found that people differ in the degree to which they attend to the experiential versus the physiological component of an emotion. It may also be that people differ in whether they are able to decrease their subjective experience of sadness versus their physiological response.

Based on the current results, either one of these two facets of CRA may serve as a relatively unique protective factor. Consistent with this idea, exploratory analyses revealed a significant interaction between CRA-SAD and CRA-SCL in predicting depressive symptoms at high levels of stress (p = .03). Further examination of the interaction revealed that participants had lower levels of depressive symptoms if they were high on either measure of CRA—being high on both did not provide added benefit. Thus, it appears that these two measures of CRA appear to make separate contributions to positive outcomes. Gaining a better understanding of these two indices of CRA will be an important avenue for future research.

Clinical Implications

Our results support a model of depression in which the regulation of negative emotions is critically important. Specifically, we found that the ability to use cognitive reappraisal to down-regulate feelings of sadness was the best predictor of depressive symptoms in interaction with cumulative stress. This provides an important step in suggesting that deficits in the ability to regulate emotion may be involved in the development of depression.

In addition, the results of the current research have the potential to inform clinical intervention and prevention programs and to lead to a better understanding of processes important for successful interventions. For example, one important component of several existing cognitive–behavioral therapies is to challenge distorted or overly negative appraisals and replace them with more realistic, positive appraisals of a situation (Brewin, 1996; Campbell-Sils & Barlow, 2007). This change of appraisals clearly overlaps with the construct of cognitive reappraisal. Much of the existing treatment research, however, has not directly measured appraisal change and has used highly selective clinical samples. The results of the present study give some support to the idea that strengthening people’s ability to use cognitive reappraisal may lead to positive clinical outcomes. Importantly, the current population-based study also suggests that the ability to change one’s appraisals has important implications for a wide range of individuals, not just patient populations.

With this in mind, it seems that interventions that target negative appraisals could be particularly effective in highly stressed populations as well as other populations at risk for depression. Individuals who are highly stressed and low in CRA may be particularly vulnerable to depression and other negative outcomes, and may be responsive to treatments that target appraisal change. If these individuals could be identified and specifically targeted, perhaps by using the laboratory paradigm described here, these vulnerable individuals could be helped before psychopathology develops or worsens.

Limitations and Future Directions

There are five important limitations to the current study that warrant further research. First, because this sample only included women, further studies are needed to determine whether the relationships observed in this study generalize to men. Second, future studies examining other outcomes such as anxiety, posttraumatic stress disorder, physical-well being, and subjective well-being are needed to examine whether CRA also predicts these outcomes in the context of stress. Samples including well-diagnosed participants with clinical levels of psychopathology are also needed to examine whether the protective effect of CRA generalizes to clinical populations. Our study provides some preliminary evidence for the clinical relevance of CRA since 56% of participants had BDI scores above the clinical threshold of 10, many of whom would likely have qualified for a DSM–IV (American Psychiatric Association, 2000) diagnosis of major depressive disorder.

Third, the cross-sectional nature of this study does not allow us to make causal claims about the effects of CRA. We here assume that CRA is relatively stable over time, similar to intelligence, for instance, thus predating the onset or worsening of depressive symptoms. It might be argued, on the other hand, that low CRA could be a function of history of mood disorders, elevated depressive symptoms, or abnormalities in the serotonergic system, rather than a risk factor. However, in the present data there was no direct relationship between CRA and depressive symptoms (only an interaction between CRA and cumulative stress), suggesting that low CRA is not simply a function of elevated depressive symptoms. Because there was no significant relationship between cumulative stress and CRA, stress also does not appear to causally influence CRA. It thus appears most parsimonious to assume that CRA is a stable, trait-like characteristic that reduces the onset of depressive symptoms at high levels of stress. However, it will be important to utilize longitudinal and experimental designs to better understand the causal effects of CRA on mental health, to examine potential bidirectional relationships between these variables, and to account for potential third variable confounds that the present study was unable to address (Kraemer, Stice, Kazdin, Offord, & Kupfer, 2001).

A fourth limitation of the current study is its reliance on one particular measure of cumulative stress, the life events scale (LES; Sarason et al., 1978). Although the LES is a widely used and well-validated measure (Denisoff & Endler, 2000; Herrington et al., 2005; Roth et al., 1994), like any one measure it is not perfect. First, it is a retrospective, self-report measure. It is possible that it is influenced by participants’ depressive symptoms. In this way, the correlation between cumulative life stress and depressive symptoms may be inflated. Converging evidence from prior research (Kendler, Karkowski, & Prescott, 1999) and the significant interaction between CRA and cumulative life stress in the prediction of depressive symptoms in the present data support that cumulative stress and depressive symptoms are not simply two different measures of the same construct. Nonetheless, it will be important for future studies to employ additional, more objective measures of life stress such as family or peer reports. Second, the LES is a cumulative measure of stress impact that sums across 18 months. This approach does not allow us to test hypotheses about the timing and duration of stressful events. For example, is CRA more adaptive in the immediate aftermath of stressors, or when more time has passed? It will be important for future research to examine this question of timing and recency of events.

A fifth important direction for future research is to better understand the validity of our measure of CRA. As Table 1 shows, this measure displayed discriminant validity with respect to trait cognitive reappraisal and emotional reactivity. Although these discriminant findings give us a good idea of what we are not measuring, they do not contribute to understanding what our measure of CRA is measuring. It is certainly promising that participants reported understanding the cognitive reappraisal instructions. They also reported trying hard to engage in cognitive reappraisal when instructed. In addition, the reappraisal instructions were high in ecological validity, and gave specific examples of how one could reappraise, making it more likely that participants were able to successfully reappraise when instructed. The instructions did not explicitly tell participants to feel less sad while reappraising, thus avoiding potential demand characteristics in the self-report data. Overall, the CRA task is high in face validity, and it seems most parsimonious to conclude that participants were at least trying to engage in reappraisal when instructed, albeit with varying levels of success. Perhaps most importantly, this measure of CRA appears to show validity for identifying people who react with depressed mood during stressful times. Further studies are needed, however, to better understand exactly what processes might contribute to high CRA.

Concluding Comment

In sum, CRA appears to be critically important in the context of stress. Individuals who are able to use reappraisal do not, on average, experience increases in depressive symptoms in high stress contexts. In this way, CRA may provide an important break in the link between stress exposure and depression. Overall, the results of the current research can help provide a better understanding of the role of emotion regulation in risk and resilience, and carry important implications for clinical interventions and prevention programs.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by University of Denver start-up funds and Grant AG031967 (IM) and the Basel Scientific Society (FW). We thank all women who participated in this study and Daniel McIntosh, Stephen Shirk, Wyndol Furman, Howard Markman, Galena Kline Rhodes, and members of the Emotion Regulation Lab at the University of Denver for feedback on previous versions of this article.

Appendix

Cognitive Reappraisal Instructions

Please watch the following film clip carefully. This time, as you watch, try to think about the situation you see in a more positive light. You can achieve this in several different ways. For example, try to imagine advice that you could give to the characters in the film clip to make them feel better. This could be advice that would help them think about the positive bearing this event could have on their lives. Or, think about the good things they might learn from this experience. Keep in mind that even though a situation may be painful in the moment, in the long run, it could make one’s life better, or have unexpected good outcomes.

Footnotes

When regression analyses were run for CRA-SAD using only these 52 participants, the interaction effect reported in Hypothesis 3 was still significant (p < .05).

When these 13 participants were included in the analyses, results were not substantially changed. In addition, when t tests were conducted to compare these nonresponders to the rest of the sample, no significant differences were found for any of the variables examined, including CRA-SCL, trait cognitive reappraisal, current depressive symptoms, cumulative stress, age, family income, or education level.

The main effect of trait reappraisal on depressive symptoms was significant and negative in both regressions (ps < .05). The standardized Beta for trait reappraisal was −0.26, while the standardized Beta for CRA-SAD × Stress was −0.22 and −0.31 for CRA-SCL × Stress. A Fisher’s Z test of the standardized betas revealed that none of these effect sizes were significantly different from one another (ps > .30). This supports the hypothesis that CRA is an important predictor of depression in addition to trait reappraisal.

Contributor Information

Allison S. Troy, Department of Psychology, University of Denver

Frank H. Wilhelm, Faculty of Psychology, University of Basel

Amanda J. Shallcross, Department of Psychology, University of Denver

Iris B. Mauss, Department of Psychology, University of Denver

References

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed., text revision. Washington, DC: Author; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett LF. Discrete emotions or dimensions? The role of valence focus and arousal focus. Cognition and Emotion. 1998;12:579–599. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT. Cognitive therapy of depression: New perspectives. In: Clayton PJ, Barnett JE, editors. Treatment of depression: Old controversies and new approaches. New York: Raven Press; 1983. pp. 265–290. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA. Internal consistencies of the original and revised Beck Depression Inventory. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1984;40:1365–1367. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(198411)40:6<1365::aid-jclp2270400615>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Garbin MG. Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory. Clinical Psychology Review. 1988;8:77–100. [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno GA. Loss, trauma, and human resilience: Have we underestimated the human capacity to thrive after extremely aversive events? American Psychologist. 2004;59:20–28. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno GA. Resilience in the face of potential trauma. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2005;14:135–138. [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno GA, Papa A, Lalande K, Westphal M, Coifman K. The importance of being flexible: The ability to both enhance and suppress emotional expression predicts long-term adjustment. Psychological Science. 2004;15:482–487. doi: 10.1111/j.0956-7976.2004.00705.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brands AM, Van Den Berg E, Manschot SM, Biessels GJ, Kappelle LJ, De Haan EH, Kessels RP. A detailed profile of cognitive dysfunction and its relation to psychological distress in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 2007;13:288–297. doi: 10.1017/S1355617707070312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewin CR. Theoretical foundations of cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety and depression. Annual Review of Psychology. 1996;47:33–57. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.47.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell-Sills L, Barlow DH. Incorporating emotion regulation into conceptualizations and treatments of anxiety and mood disorders. In: Gross JJ, editor. Handbook of emotion regulation. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2007. pp. 542–560. [Google Scholar]

- Carrico AW, Antoni MH, Weaver KE, Lechner SC, Schneiderman N. Cognitive-behavioural stress management with HIV-positive homosexual men: Mechanisms of sustained reductions in depressive symptoms. Chronic Illness. 2005;1:207–215. doi: 10.1177/17423953050010030401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dandoy AC, Goldstein AC. The use of cognitive appraisal to reduce stress reactions: A replication. Journal of Social Behavior and Personality. 1990;5:275–285. [Google Scholar]

- Denisoff E, Endler NS. Life experiences, coping, and weight preoccupation in young adult women. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science. 2000;32:97–103. [Google Scholar]

- Feldman CT, Bensing JM, deRuijter A. Worries are the mother of many diseases: General practitioners and refugees in the Netherlands on stress, being ill, and prejudice. Patient Education and Counseling. 2007;65:369–380. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2006.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman Barrett L. The relationships among momentary emotion experiences, personality descriptions, and retrospective ratings of emotion. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1997;23:1100–1110. [Google Scholar]

- Feldman Barrett LA. Valence focus and arousal focus: Individual differences in the structure of affective experience. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;69:153–166. [Google Scholar]

- Folkman S, Lazarus RS. If it changes it must be a process: Study of emotion and coping during three stages of a college examination. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1985;48:150–170. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.48.1.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson BL, Levenson RW. Positive emotions speed recovery from the cardiac sequelae of negative emotions. Cognition and Emotion. 1998;12:191–220. doi: 10.1080/026999398379718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freitas AL, Downey G. Resilience: A dynamic perspective. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 1998;22:263–285. [Google Scholar]

- Garnefski N, Kraaij V. Relationships between cognitive emotion regulation strategies and depressive symptoms: A comparative study of five specific samples. Personality and Individual Differences. 2006;40:1659–1669. [Google Scholar]

- Garnefski N, Kraaij V, Spinhoven P. Negative life events, cognitive emotion regulation and emotional problems. Personality and Individual Differences. 2001;30:1311–1327. [Google Scholar]

- Gotlib IH, Hammen CL, editors. Handbook of depression. New York: Guilford Press; 2002. Introduction. [Google Scholar]

- Gross JJ. Antecedent and response-focused emotion regulation: Divergent consequences for experience, expression, and physiology. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;74:224–237. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.74.1.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross JJ, John OP. Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: Implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003;85:348–362. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.85.2.348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross JJ, Munoz RF. Emotion regulation and mental health. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 1995;2:151–164. [Google Scholar]

- Gross JJ, Thompson RA. Emotion regulation: Conceptual foundations. In: Gross JJ, editor. Handbook of emotion regulation. New York: Guilford Press; 2007. pp. 3–24. [Google Scholar]

- Hagemann D, Naumann E, Maier S, Becker G, Lurken A, Bartussek L. The assessment of affective reactivity using films: Validity, reliability, and sex differences. Personality and Individual Differences. 1999;26:627–639. [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C. Stress and depression. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2005;1:293–319. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.143938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C, Davila J, Brown G, Ellicott A, Gitlin M. Psychiatric history and stress: Predictors of severity of unipolar depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1992;101:45–52. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.101.1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrington AN, Matheny KB, Curlette WL, McCarthy CJ, Penick J. Lifestyles, coping resources, and negative life events as predictors of emotional distress in university women. Journal of Individual Psychology. 2005;61:343–364. [Google Scholar]

- Hodgson R, Rachman S. Desynchrony in measures of fear. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1974;12:319–326. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(74)90006-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson DC, Malmstadt JR, Larson CL, Davidson RJ. Suppression and enhancement of emotional responses to unpleasant pictures. Psychophysiology. 2000;37:512–522. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joormann J, Siemer M, Gotlib IH. Mood regulation in depression: Differential effects of distraction and recall of happy memories on sad mood. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2007;116:484–490. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.116.3.484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Karkowski LM, Prescott CA. Causal relationship between stressful life events and the onset of major depression. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;156:837–841. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.6.837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Thornton LM, Gardner CO. Stressful life events and previous episodes in the etiology of major depression in women: An evaluation of the ‘Kindling’ hypothesis. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2000;157:1243–1251. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.8.1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh KB, Choe E, Song JE, Lee EH. Effect of coping on endicrinoimmune functions in different stress situations. Psychiatry Research. 2006;143:223–234. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2005.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraaij V, Pruymboom E, Garnefski N. Cognitive coping and depressive symptoms in the elderly: A longitudinal study. Aging and Mental Health. 2002;6:275–281. doi: 10.1080/13607860220142387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer HC, Stice E, Kazdin A, Offord D, Kupfer D. How do risk factors work together? Mediators, moderators, and independent, overlapping, and proxy risk factors. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;158:848–856. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.6.848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreibig SD, Wilhelm FH, Roth WT, Gross JJ. Cardiovascular, electrodermal, and respiratory response patterns to fear- and sadness-inducing films. Psychophysiology. 2007;44:787–806. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2007.00550.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunzmann U, Gruhn D. Age differences in emotional reactivity: The sample case of sadness. Psychology and Aging. 2005;20:47–59. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.20.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange A, van de Ven JP, Schrieken B. Interapy: Treatment of posttraumatic stress via the internet. Cognitive Behavior Therapy. 2003;32:110–124. doi: 10.1080/16506070302317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau JY, Eley TC. Attributional style as a risk marker of genetic effects for adolescent depressive symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2008;117:849–859. doi: 10.1037/a0013943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS, DeLongis A, Folkman S, Gruen R. Stress and adaptational outcomes: The problem of confounded measures. American Psychologist. 1985;40:770–779. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York: Springer; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS, Opton EM, Jr, Nomikos MS, Rankin NO. The principle of short-circuiting of threat: Further evidence. Journal of Personality. 1965;33:622–635. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1965.tb01408.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenz FO, Wickrama KAS, Conger RD, Elder GH., Jr The short-term and decade-long effects of divorce on women’s midlife health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2006;47:111–125. doi: 10.1177/002214650604700202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauss IB, Cook CL, Cheng JYJ, Gross JJ. Individual differences in cognitive reappraisal: Experiential and physiological responses to an anger provocation. International Journal of Psychophysiology. 2007;66:116–124. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2007.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauss IB, Levenson RW, McCarter L, Wilhelm FH. The tie that binds? Coherence among emotion experience, behavior, and physiology. Emotion. 2005;5:175–190. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.5.2.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy CJ, Lambert RG, Moller NP. Preventive resources and emotion regulation expectances as mediators between attachment and college students’ stress outcomes. International Journal of Stress Management. 2006;13:1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Monroe SM, Hadjiyannakis K. The social environment and depression: Focusing on severe life stress. In: Gotlib IH, Hammen CL, editors. Handbook of depression. New York: Guilford Press; 2002. pp. 314–340. [Google Scholar]

- Moore SA, Zoellner LA, Mollenholt N. Are expressive suppression and cognitive reappraisal associated with stress-related symptoms? Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2008;46:993–1000. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2008.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morales JR, Guerra NG. Effects of multiple context and cumulative stress on urban children’s adjustment in elementary school. Child Development. 2006;77:907–923. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00910.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris MC, Ciesla JA, Garber J. A prospective study of the cognitive-stress model of depressive symptoms in adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2008;117:719–734. doi: 10.1037/a0013741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moskowitz JT, Hult JR, Bussolari C, Acree M. What works in coping with HIV? A meta-analysis with implications for coping with serious illness. Psychological Bulletin. 2009;135:121–141. doi: 10.1037/a0014210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong AD, Bergeman CS, Bisconti TL, Wallace KA. Psychological resilience, positive emotions, and successful adaptation to stress in later life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2006;91:730–749. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.91.4.730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell K, Wardle J, Dantzer C, Steptoe A. Alcohol consumption and symptoms of depression in young adults from 20 countries. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2006;67:837–840. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortony A, Clore GL, Collins A. The cognitive structure of emotions. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Pakenham KI. Relations between coping and positive and negative outcomes in carers of persons with Multiple Sclerosis (MS) Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings. 2005;12:25–38. [Google Scholar]

- Parkinson B, Totterdell P. Classifying affect-regulation strategies. Cognition and Emotion. 1999;13:277–303. [Google Scholar]

- Pearlstein TB, Zlotnick C, Battle CL, Stuart S, O’Hara MW, Price AB, Howard M. Patient choice of treatment for post-partum depression: A pilot study. Archives of Women’s Mental Health. 2006;9:303–308. doi: 10.1007/s00737-006-0145-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennebaker JW, Chung CK. Expressive writing, emotional upheavals, and health. In: Friedman H, Silver R, editors. Handbook of health psychology. New York: Oxford University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]