Abstract

Objectives

To assess the use of prognostic patient factors and predictive tests in clinical decision making for spinal fusion in patients with chronic low back pain.

Design and setting

Nationwide survey among spine surgeons in the Netherlands.

Participants

Surgeon members of the Dutch Spine Society were questioned on their surgical treatment strategy for chronic low back pain.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

The surgeons' opinion on the use of prognostic patient factors and predictive tests for patient selection were addressed on Likert scales, and the degree of uniformity was assessed. In addition, the influence of surgeon-specific factors, such as clinical experience and training, on decision making was determined.

Results

The comments from 62 surgeons (70% response rate) were analysed. Forty-four surgeons (71%) had extensive clinical experience. There was a statistically significant lack of uniformity of opinion in seven of the 11 items on prognostic factors and eight of the 11 items on predictive tests, respectively. Imaging was valued much higher than predictive tests, psychological screening or patient preferences (all p<0.01). Apart from the use of discography and long multisegment fusions, differences in training or clinical experience did not appear to be of significant influence on treatment strategy.

Conclusions

The present survey showed a lack of consensus among spine surgeons on the appreciation and use of predictive tests. Prognostic patient factors were not consistently incorporated in their treatment strategy either. Clinical decision making for spinal fusion to treat chronic low back pain does not have a uniform evidence base in practice. Future research should focus on identifying subgroups of patients for whom spinal fusion is an effective treatment, as only a reliable prediction of surgical outcome, combined with the implementation of individual patient factors, may enable the instalment of consensus guidelines for surgical decision making in patients with chronic low back pain.

Article summary

Article focus

What is the level of professional consensus among spine surgeons regarding spinal fusion surgery for chronic low back pain?

How are tests for patient selection appreciated and to what extent are they used in clinical practice?

Are prognostic patient factors incorporated in the process of surgical decision making for chronic low back pain?

Key messages

In clinical practice, there is no professional consensus on surgical treatment strategy for chronic low back pain.

Prognostic patient factors as well as tests for patient selection are not consistently used in clinical decision making for spinal fusion.

Because of a lack of consensus on spinal fusion strategy for chronic low back pain in clinical practice, no guidelines for proper patient counselling can be installed at present.

Strengths and limitations of this study

A survey among physicians provides valuable insight in the actual decision-making process in clinical practice. Understanding contributory factors in treatment strategy may help in the creation of consensus guidelines.

The introduction of an interviewer bias could be avoided by the use of a neutral intermediary instead of direct questions from peers in spine surgery.

This study focused on surgeon members of the Dutch Spine Society whose practice may not reflect that of all surgeons performing spinal fusion for chronic low back pain. Moreover, no information on conservative treatment options was acquired.

To define consensus, we chose for uniformity of opinion of at least 70%, which we considered to be sufficient for implementation in guidelines. Such a cut-off level remains arbitrary.

Introduction

Chronic low back pain has become one of the main causes of disability in the industrialised world with reported lifetime prevalences of up to 85%.1 In the Netherlands, a small Western European country (16.5 million inhabitants) with a relatively high rate of spine surgery,2 the annual costs of back pain were estimated at €;4.4 billion, which are mainly employment-related costs (lost productivity due to work absenteeism).3

Spinal fusion of a painful or degenerative segment can be beneficial to some patients, but it remains a controversial treatment.4 5 In the first Cochrane Review in 1999, no evidence on the effectiveness of fusion for lumbar degenerative disc disease or low back pain was found as compared with natural history, placebo or conservative treatment.6 In the updated Cochrane Review in 2005,7 two randomised controlled trials were included. First, a Swedish trial reported a better outcome of patients treated with spinal fusion compared with those who received standard conservative care,8 although at longer follow-up this beneficial effect attenuated.9 Next, a Norwegian randomised controlled trial that compared fusion surgery with cognitive behavioural based exercise therapy10 showed similar results for both treatment modalities at 1-year follow-up. Similarly, in the more recent British spine stabilisation trial, no clear evidence was found that spinal fusion was more beneficial than an intensive rehabilitation programme at 2-year follow-up.11 Moreover, fusion had a much higher complication rate in this trial and appeared to be less cost-effective than intensive rehabilitation.12 13

Proper patient selection may improve the outcome of fusion for which several prognostic factors and predictive tests have been reported.4 14–19 However, epidemiological research reveals large variation in fusion rates between countries and even between different regions within the same country,20 21 suggesting a poor level of professional consensus. Understanding contributory factors in treatment strategy of surgeons may clarify some of these observed variations and help to create consensus guidelines for clinical decision making.

Therefore, we conducted a national survey among spine surgeons in the Netherlands with the aim to assess the surgeons' opinion on prognostic patient factors known from the literature, as well as the use of predictive tests for spinal fusion in clinical practice. In addition, the degree of uniformity in decision making was determined.

Materials and methods

A 25-question survey (see appendix 1) was sent by mail to all surgeon members of the Dutch Spine Society, by Memic, a Center for Data and Information Management, University of Maastricht, the Netherlands (http://www.memic.unimaas.nl). In an accompanying letter, the background rationale for the enquiry, as well as the voluntary and confidential nature, was stressed and the surgeons were reassured that individual comments would remain anonymous.

The questionnaire concerned the selection for spinal fusion of patients with low back pain caused by degenerative lumbar disc disease without signs of neurological deficit, spinal stenosis, deformity or spondylolisthesis and in the absence of trauma, tumour or infections. This group was further referred to as chronic low back pain patients. For clarity, the questionnaire had first been evaluated and revised by a clinical researcher and two orthopaedic surgeons. Most questions could be answered according to a 5-point Likert scale. Surgeon-specific factors (eg, discipline, clinical experience), the influence of patient factors (prognostic factors as reported in literature) and the use of tests for patient selection (eg, provocative discography) were addressed. The respondents were specifically asked to rely on their own individual opinion and management in practice.

Those who had not responded received a second call by mail after 2 months, and final inclusion was set another 2 months later. Data were entered into Excel (Microsoft, Corp., Redmond, Washington, USA), and all inconsistencies were resolved. Unanswered questions were coded as missing. Descriptive statistics was used in which all frequencies were based on the number of valid responders.

For analysis, the answers on the 5-point Likert scale were merged into one intermediate option (‘neutral’) and two opposite categories (‘always/almost always’ vs ‘never/almost never’ and ‘fully/globally agree’ vs ‘globally/fully disagree’). The data were processed with Statistical Package for the Social Sciences software (SPSS, Inc.). Pearson's χ2 test was used to evaluate whether surgeon-specific factors were associated with clinical decision making. Uniformity of opinion was defined to be present if ≥70% of the respondents answered similarly. In other words, there was no consensus if the proportion of the largest category was statistically significantly <70% (Pearson's χ2 test). Differences in mean values rating the impact of factors on decision making were tested by independent t test for equality of means. The level of significance was set at p<0.05.

Results

Nine of the 150 surveyed surgeons (89 orthopaedic surgeons and 61 neurosurgeons) had ended their professional career and nine respondents stated not to perform spinal surgery anymore. Of the remaining 132 active spine surgeons, 93 (70%) completed and returned the questionnaire. Thirty-one of the 93 respondents (33%) declared not to perform spinal fusion for low back pain and were excluded from further analysis. The characteristics of the final group of 62 respondents are listed in table 1. The level of experience for neurosurgeons and orthopaedic surgeons was equal: 11 of 16 (69%) vs 33 of 46 (72%) worked ≥10 years in clinical practice, respectively.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the 62 respondents

| Orthopaedic surgeons (n) | Neurosurgeons (n) | All respondents (n) | |

| No. of respondents | 46 | 16 | 62 |

| Age | |||

| <50 years | 22 | 10 | 32 |

| ≥50 years | 24 | 6 | 30 |

| Clinical experience | |||

| <10 years | 13 | 5 | 18 |

| ≥10 years | 33 | 11 | 44 |

| Type of hospital | |||

| University/specialised | 13 | 5 | 18 |

| General | 33 | 11 | 44 |

| No. of fusions for CLBP/year | |||

| 1–10 | 24 | 9 | 33 |

| 10–25 | 9 | 6 | 15 |

| 25–50 | 7 | 1 | 8 |

| ≥50 | 6 | 0 | 6 |

CLBP, chronic low back pain.

Prognostic factors

The respondents' comments on prognostic factors are listed in table 2. For seven of the 11 items, there was no consensus (significantly <70% uniformity of opinion).

Table 2.

Respondents' opinion to what extent patient-specific prognostic factors influence their clinical decision making in the treatment of CLBP

| Patient factor |

p Value* | |||

| Maximum number of levels for fusion | 1 Level | 2 Levels | ≥3 Levels | |

| 18 (30.5) | 23 (39.0) | 18 (30.5) | <0.001 | |

| Minimum age patient | <20 years | 20–30 years | ≥30 years | <0.001 |

| 15 (24.6) | 25 (41.0) | 21 (34.4) | ||

| Maximum age patient | 40–50 years | 50–60 years | ≥60 years | NS |

| 5 (8.1) | 12 (19.4) | 45 (72.5) | ||

| Minimal length conservative therapy | <6 months | 6 months to 1 year | ≥1 year | NS |

| 3 (4.8) | 36 (58.1) | 23 (37.1) | ||

| Maximum body mass index | <31 | 31–37 | ≥37 | <0.001 |

| 29 (46.8) | 18 (29.0) | 15 (24.2) | ||

| Maximum number of cigarettes/day | 0 | 1–20 | ≥20 | <0.001 |

| 29 (47.5) | 7 (11.4) | 25 (40.9) | ||

| Referral overweight patients to dietician | Always | Sometimes | Never | <0.001 |

| 29 (46.8) | 20 (32.3) | 13 (21.0) | ||

| Psychological screening referral | Always | Sometimes | Never | <0.001 |

| 10 (16.2) | 28 (45.2) | 24 (38.7) | ||

| Different criteria for primary DDD vs prior spine surgery | Agree | Neutral | Disagree | NS |

| 44 (71.0) | 8 (12.9) | 10 (16.1) | ||

| Work status affects outcome | Agree | Neutral | Disagree | <0.001 |

| 29 (46.7) | 17 (27.4) | 16 (25.9) | ||

| Litigation procedures affect outcome | Agree | Neutral | Disagree | NS |

| 43 (69.3) | 9 (14.5) | 10 (16.2) | ||

The numbers listed are percentages of valid responses.

χ2 test: p<0.05 means significantly <70% consensus, NS implies uniformity.

DDD, degenerative disc disease; NS, not significant.

More than 70% of the respondents would fuse patients over 60 years old for back pain. Years of clinical experience or specialty did not appear to be of influence (p=0.504 and p=0.690, respectively).

Eight of 18 academic surgeons and 32 of 43 spine surgeons working in general hospitals operated on patients below 30 for back pain (p=0.025).

Fourteen of 46 orthopaedic surgeons fused patients below 20 for back pain versus only one of 15 neurosurgeons (p=0.063). Eighteen orthopaedic surgeons performed fusion of three or more levels for low back pain, whereas no neurosurgeon did (p=0.003).

Tests for patient selection

The surgeons' appreciation and use of predictive tests are listed in tables 3 and 4, respectively. Apart from MRI, there was no uniformity regarding the value of these tests for clinical decision making.

Table 3.

Respondents' opinion on predictive tests for clinical decision making

| Predictive test | Agree (%) | Neutral (%) | Disagree (%) | p Value* |

| MRI sufficient for decision making | 10 (16.1) | 11 (17.7) | 41 (66.1) | NS |

| Cast immobilisation valuable test | 25 (40.3) | 15 (24.2) | 22 (35.5) | <0.001 |

| Cast immobilisation too unpleasant | 11 (17.7) | 16 (25.8) | 35 (56.5) | 0.028 |

| PD proven valuable test | 23 (37.7) | 16 (26.2) | 22 (36.0) | <0.001 |

| PD too many complications | 3 (4.9) | 14 (23.0) | 44 (72.1) | NS |

| TETF valuable test | 8 (13.4) | 33 (55.0) | 19 (31.6) | 0.011 |

| TETF too many complications | 20 (32.7) | 31 (50.8) | 10 (16.4) | 0.001 |

The numbers listed are valid responses and respective percentages.

χ2 test: p<0.05 means significantly <70% consensus, NS implies uniformity.

NS, not significant; PD, provocative discography; TETF, temporary external transpedicular fixation.

Table 4.

The use of predictive tests by the surgeons in clinical practice

| Use of test | Always (%) | Sometimes (%) | Never (%) | p Value* |

| Facet joint blocks | 5 (8.1) | 32 (51.6) | 25 (40.3) | 0.002 |

| Cast immobilisation | 20 (32.8) | 23 (37.7) | 18 (29.6) | <0.001 |

| PD | 25 (42.4) | 10 (16.9) | 24 (40.7) | <0.001 |

| TETF | 0 (0.0) | 3 (4.9) | 58 (95.1) | NS |

The numbers listed are valid responses and their respective percentages.

χ2 test: p<0.05 means significantly <70% consensus, NS implies uniformity.

NS, not significant; PD, provocative discography; TETF, temporary external transpedicular fixation.

Mainly orthopaedic surgeons (21 of 46 vs 2 of 16 neurosurgeons, p=0.025) considered provocative discography to be a valid predictor of fusion. Spine surgeons working in general hospitals (20 of 43) appeared to believe more in the test than academic surgeons did (3 of 18, p=0.028). There was no relation with clinical experience (p=0.406). Apart from the use of discography, differences in discipline or clinical experience did not appear to be of significant influence on treatment strategy. In the evaluation of chronic low back pain, no other predictive tests than those mentioned in tables 3 and 4 were used on a regular basis.

Individual decision making in clinical practice

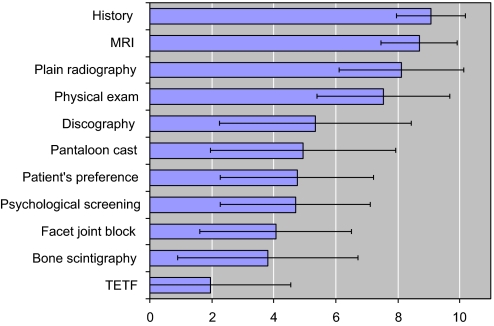

Table 5 and figure 1 show the importance of predictive tests and prognostic factors for clinical decision making as rated on a scale from 0 to 10. Patient history and imaging were valued significantly higher than predictive tests, psychological screening or patient preferences (all respective comparisons: p<0.01, independent t test).

Table 5.

The importance of listed factors in clinical decision making (presented as mean ± SD) as rated by the respondents on a scale from 0 (no importance) to 10 (maximal importance)

| Mean ± SD | |

| History | 9.06±1.11 |

| MRI | 8.69±1.24 |

| Plain radiographs | 8.11±2.01 |

| Physical examination | 7.53±2.15 |

| Discography | 5.34±3.09 |

| Pantaloon cast | 4.95±2.99 |

| Patient's preference | 4.75±2.25 |

| Psychological screening | 4.70±2.42 |

| Facet joint block | 4.06±2.46 |

| Bone scintigraphy | 3.80±2.59 |

| TETF | 1.96±2.59 |

TETF, temporary external transpedicular fixation.

Figure 1.

The importance of listed factors in clinical decision making (presented as mean ± SD), as rated by the respondents on a scale from 0 (no importance) to 10 (maximal importance). TETF, temporary external transpedicular fixation.

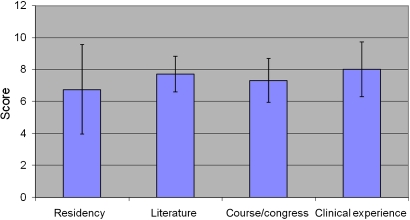

The impact of surgeon-specific factors on treatment strategy is listed in table 6 and figure 2. Experience was rated highest (mean±SD, 8.0±1.7) as compared with findings from literature (7.7±1.1, p=0.26), scientific courses (7.3±1.4, p=0.01) and training (6.8±2.8, p<0.01).

Table 6.

Factors that influence clinical decision making for chronic low back pain (presented as mean ± SD), as rated by respondents on a scale from 0 (no influence) to 10 (maximal influence)

| Mean ± SD | |

| Residency/training | 6.76±2.80 |

| Literature | 7.72±1.11 |

| Course/congress | 7.31±1.37 |

| Clinical experience | 8.02±1.72 |

Figure 2.

Factors that influence clinical decision making for chronic low back pain (presented as mean ± SD), as rated by respondents on a scale from 0 (no influence) to 10 (maximal influence).

Twenty-seven (45%) surgeons responded to have a protocol for decision making to which they frequently or always adhered. Of those 35 respondents who did not have such a protocol, 23 (68%) replied that there should be guidelines. In other words, 50 respondents (83%) felt that clinical guidelines in the management of CLBP patients are prerequisite.

Discussion

This study presents the results of the first nationwide survey among spine surgeons regarding clinical decision making for spinal fusion in patients with chronic low back pain. The response rate was adequate (70%), and the majority of the respondents (71%) had extensive clinical experience in spinal surgery. A considerable heterogeneity in the use and appreciation of predictive tests was observed. Prognostic patient factors were not consistently incorporated in clinical decision making.

Strengths and weaknesses

This survey focused on surgeon members of the Dutch Spine Society whose practice may not reflect that of all surgeons performing spinal fusion for low back pain. This may have produced a selection bias. It is reasonable, however, to expect that surgeons with a special interest in the spine are exactly those to be most aware of guidelines and research findings in the field.

To define consensus, we chose for uniformity of opinion of ≥70% of the respondents. We felt that this level of agreement should be sufficient for implementation in guidelines. Such a cut-off level remains, of course, arbitrary and debatable.

The introduction of an interviewer bias could be avoided by employing Memic, Center for Data and Information Management, as a neutral intermediary. In this way, surgeons could feel free to answer what they personally felt or practiced, as opposed to what they thought would be considered ‘correct’.

For statistical analysis, the 5-point Likert scale responses were merged into three categories, which may have simplified the respondents' opinion on the management of low back pain in practice.

Comparison with related research

According to literature, older age is an acknowledged predictor of poor outcome.14 Nevertheless, almost three-quarters (73%) of the surgeons fused patients above 60 for low back pain.

In literature, two- or three-level fusions have proven higher rates of pseudarthrosis with lower patient satisfaction as compared with single-level fusions.5 14 Over 30% of the surgeons would consider fusion of three levels or more.

Although the literature says that fusion surgery is not recommended unless 2 years of conservative treatment have failed,22 63% of the surgeons felt that <1 year of conservative therapy is enough to consider fusion.

In literature, obesity is an independent risk factor for low back pain, and surgery in these patients is significantly associated with major complications, such as thromboembolism and infection.19 Nevertheless, 53% of the surgeons would operate for chronic low back pain on obese patients and 24% on the morbid obese. Less than half of the surgeons (47%) consistently referred overweight patients to a dietician.

In literature, smoking is known to be an independent risk factor for low back pain15 and associated with worse results of spinal fusion.12 Among surgeons, there was no consensus regarding smoking: about 41% would fuse heavy smokers, whereas 48% would not operate smokers for back pain.

According to literature, psychologically stressful work is associated with low back pain and disability,17 and it has been reported that psychological distress, depressive mood and somatisation lead to an increased risk of chronicity.18 In addition, presurgical depression is associated with worse patient outcome after lumbar fusion.14 In contrast, only 16% of the surgeons referred patients routinely for psychological screening and 39% never referred for this purpose at all.

There is strong evidence in literature that clinical interventions are not effective in returning patients back to work once they have been off work for a longer time.22 About half of the surgeons agreed that the work status of patients with low back pain affects outcome considerably and 69% acknowledged that litigation or workers' compensation are of great influence on decision making, as they have been associated with persisting pain and disability.17

Two-thirds (66%) of the respondents considered findings on plain radiographs and MRI scan alone to be insufficient for surgical decision making (table 3). This is in accordance with the literature indicating that degenerative or black discs on MRI do not appear to have a strong clinical relevance23 24 and that there is no correlation between radiographic signs of degeneration and clinical outcome.25

Opinion differed about trial immobilisation with a pantaloon cast: 40% of the respondents agreed that it is a valuable test and 36% disagreed. This resembles conflicting reports from the literature claiming that the test is not predictive of fusion outcome26 or that only in highly selected patient groups the pantaloon cast test may be of value.27

According to literature, provocative discography is a controversial test, which is highly variable in chronic pain patients and can also be positive in pain-free individuals.28 Its value in predicting the outcome of fusion for low back pain is debated,16 29 which was reflected in the completely contradictory surgeons' opinions. Trial immobilisation with a temporary external fixator is known for its high complication rate,30 and because of ambiguous results, its use is not recommended.31 In the present survey, external fixation was not frequently used (94% never used it) and only 13% of the surgeons believed in its predictive value.

In literature, lumbar facet injections have been reported not to be predictive of either arthrodesis or non-surgical treatment of back pain.32 Accordingly, only 8% of the surgeons used facet joint blocks on a regular basis as a predictor of spinal fusion.

Clinical relevance and implications for clinicians and policy makers

The lack of consensus among spine surgeons as found in the present survey could not be explained by differences in training or clinical experience. Apart from the use of discography and long multilevel fusions, the surgeons' discipline and years in practice did not appear to be of significant influence on treatment strategy. More likely, the observed heterogeneity of opinion reflects the absence of consistent high-quality evidence for the validity of prognostic factors and predictive tests.33 As there is no generally acknowledged superior approach for low back pain, substantial variations that exist between practices are caused by clinical uncertainty as to what constitutes the best of care.

In a survey among expert spine surgeons, bad patient selection and disproportionate preoperative expectations were considered to be the major factors for poor outcome in spinal surgery.34 At present, consistent evidence on tests or tools that reliably predict the outcome of fusion is lacking.35 Moreover, to provide a reliable estimation of the effectiveness of surgery, preferences of the individual patient, as well as psychological and social factors that may affect outcome, should be assessed.36 To achieve realistic patient expectations of surgery, good patient counselling should be evidence based, that is, determined by the best available clinical evidence from systematic research,37 combined with the individual surgeon's expertise and expectation of treatment success.38 As the present survey shows, prognostic factors are not consistently incorporated at all in the surgical decision-making process. Lack of consensus among surgeons hampers the implementation of clinical guidelines, which are needed for proper patient counselling.

Future research should thus focus on identifying a subgroup of patients for whom spinal fusion is a predictable and effective treatment. If the results of fusion could be improved by better patient selection, there could be a role for spinal fusion as the treatment of choice for this particular subgroup of patients. A reliable prediction of surgical outcome, combined with the implementation of individual patient factors, would enable the instalment of clinical guidelines for surgical decision making. Such guidelines are needed for patient counselling and for communication with insurers, policy makers and other healthcare providers who are involved in the management of chronic low back pain.

Conclusions

The present survey consistently showed a lack of consensus among spine surgeons in surgical decision making. Despite high levels of training and continuous medical education, patient selection for fusion surgery in the treatment of chronic low back pain does not have a uniform evidence base in clinical practice.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the members of the Dutch Spine Society for their participation in this study.

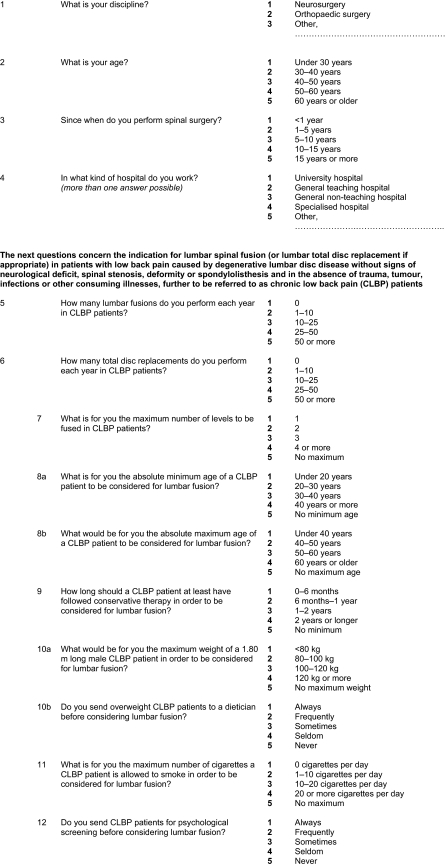

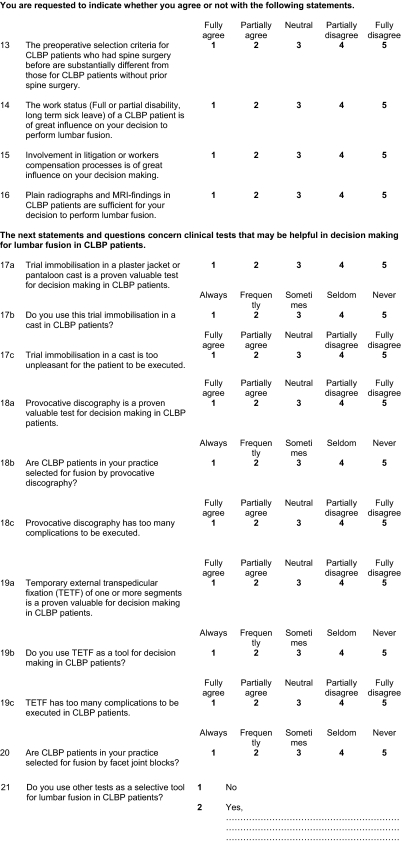

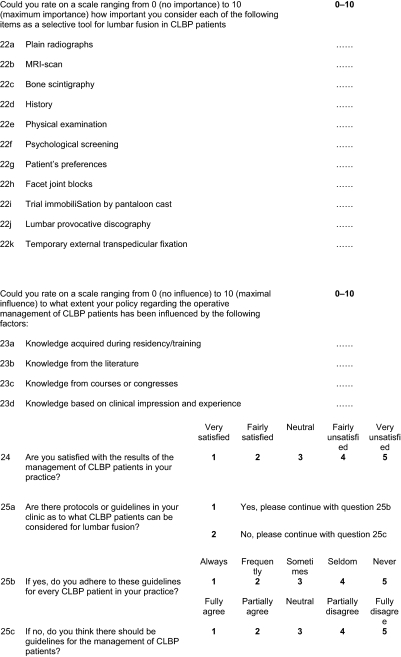

Appendix 1. Questionnaire on decision making for lumbar spinal fusion in chronic low back pain patients

|

|

|

Footnotes

To cite: Willems P, de Bie R, Öner C, et al. Clinical decision making in spinal fusion for chronic low back pain. Results of a nationwide survey among spine surgeons. BMJ Open 2011;1:e000391. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000391

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the Unified Competing Interest form at http://www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author).

Ethics approval: This study was a survey among physicians, not among patients.

Contributors: PW: conception and design of the study, acquisition, analysis and interpretation of the data, drafting the article and approval of the final version to be published. RdB: design of the study, acquisition and analysis of the data, revising the article and approval of the final version to be published. CÖ: design of the study, analysis and interpretation of the data, revising the article and approval of the final version to be published. RC: design of the study, analysis and interpretation of the data, revising the article and approval of the final version to be published. MdK: conception and design of the study, analysis and interpretation of the data, revising the article and approval of the final version to be published.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: All data can be found on doi:10.5061/dryad.7p65c8p4.

References

- 1.Walker BF. The prevalence of low back pain: a systematic review of the literature from 1966 to 1998. J Spinal Disord 2000;13:205–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cherkin DC, Deyo RA, Loeser JD, et al. An international comparison of back surgery rates. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1994;19:1201–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Slobbe LCJ, Kommer GJ, Smit JM, et al. Kosten van ziekten in Nederland 2003. RIVM rapport 270751010. Bilthoven: RIVM, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krismer M. Fusion of the lumbar spine. A consideration of the indications. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2002;84:783–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Turner JA, Ersek M, Herron L, et al. Patient outcomes after lumbar spinal fusions. JAMA 1992;268:907–11 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gibson JN, Grant IC, Waddell G. The Cochrane review of surgery for lumbar disc prolapse and degenerative lumbar spondylosis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1999;24:1820–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gibson JN, Waddell G. Surgery for degenerative lumbar spondylosis: updated Cochrane Review. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2005;30:2312–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fritzell P, Hagg O, Wessberg P, et al. 2001 Volvo Award Winner in Clinical Studies: Lumbar fusion versus nonsurgical treatment for chronic low back pain: a multicenter randomized controlled trial from the Swedish Lumbar Spine Study Group. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2001;26:2521–32; discussion 2532–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fritzell P, Hagg O, Jonsson D, et al. Cost-effectiveness of lumbar fusion and nonsurgical treatment for chronic low back pain in the Swedish Lumbar Spine Study: a multicenter, randomized, controlled trial from the Swedish Lumbar Spine Study Group. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2004;29:421–34; discussion Z3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brox JI, Sorensen R, Friis A, et al. Randomized clinical trial of lumbar instrumented fusion and cognitive intervention and exercises in patients with chronic low back pain and disc degeneration. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2003;28:1913–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fairbank J, Frost H, Wilson-MacDonald J, et al. Randomised controlled trial to compare surgical stabilisation of the lumbar spine with an intensive rehabilitation programme for patients with chronic low back pain: the MRC spine stabilisation trial. BMJ 2005;330:1233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wilson-MacDonald J, Fairbank J, Frost H, et al. The MRC spine stabilization trial: surgical methods, outcomes, costs, and complications of surgical stabilization. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2008;33:2334–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rivero-Arias O, Campbell H, Gray A, et al. Surgical stabilisation of the spine compared with a programme of intensive rehabilitation for the management of patients with chronic low back pain: cost utility analysis based on a randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2005;330:1239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.DeBerard MS, Masters KS, Colledge AL, et al. Outcomes of posterolateral lumbar fusion in Utah patients receiving workers' compensation: a retrospective cohort study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2001;26:738–46; discussion 47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deyo RA, Bass JE. Lifestyle and low-back pain. The influence of smoking and obesity. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1989;14:501–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Colhoun E, McCall IW, Williams L, et al. Provocation discography as a guide to planning operations on the spine. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1988;70:267–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Katz JN. Lumbar disc disorders and low-back pain: socioeconomic factors and consequences. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2006;88(Suppl 2):21–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pincus T, Burton AK, Vogel S, et al. A systematic review of psychological factors as predictors of chronicity/disability in prospective cohorts of low back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2002;27:E109–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Patel N, Bagan B, Vadera S, et al. Obesity and spine surgery: relation to perioperative complications. J Neurosurg Spine 2007;6:291–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Katz JN. Lumbar spinal fusion. Surgical rates, costs, and complications. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1995;20:78S–83S [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weinstein JN, Lurie JD, Olson PR, et al. United States' trends and regional variations in lumbar spine surgery: 1992-2003. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2006;31:2707–14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Airaksinen O, Brox JI, Cedraschi C, et al. Chapter 4. European guidelines for the management of chronic nonspecific low back pain. Eur Spine J 2006;15(Suppl 2):S192–300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boden SD, McCowin PR, Davis DO, et al. Abnormal magnetic-resonance scans of the cervical spine in asymptomatic subjects. A prospective investigation. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1990;72:1178–84 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jarvik JJ, Hollingworth W, Heagerty P, et al. The Longitudinal Assessment of Imaging and Disability of the Back (LAIDBack) Study: baseline data. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2001;26:1158–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van Tulder MW, Assendelft WJ, Koes BW, et al. Spinal radiographic findings and nonspecific low back pain. A systematic review of observational studies. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1997;22:427–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Axelsson P, Johnsson R, Stromqvist B, et al. Orthosis as prognostic instrument in lumbar fusion: no predictive value in 50 cases followed prospectively. J Spinal Disord 1995;8:284–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Willems PC, Elmans L, Anderson PG, et al. The value of a pantaloon cast test in surgical decision making for chronic low back pain patients: a systematic review of the literature supplemented with a prospective cohort study. Eur Spine J 2006;15:1487–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Carragee EJ, Tanner CM, Khurana S, et al. The rates of false-positive lumbar discography in select patients without low back symptoms. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2000;25:1373–80; discussion 1381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Willems PC, Elmans L, Anderson PG, et al. Provocative discography and lumbar fusion: is preoperative assessment of adjacent discs useful? Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2007;32:1094–9; discussion 1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bednar DA. Failure of external spinal skeletal fixation to improve predictability of lumbar arthrodesis. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2001;83-A:1656–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Elmans L, Willems PC, Anderson PG, et al. Temporary external transpedicular fixation of the lumbosacral spine: a prospective, longitudinal study in 330 patients. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2005;30:2813–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Esses SI, Moro JK. The value of facet joint blocks in patient selection for lumbar fusion. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1993;18:185–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hemingway H, Riley RD, Altman DG. Ten steps towards improving prognosis research. BMJ 2009;339:b4184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Haefeli M, Elfering A, Aebi M, et al. What comprises a good outcome in spinal surgery? A preliminary survey among spine surgeons of the SSE and European spine patients. Eur Spine J 2008;17:104–16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Deyo RA, Nachemson A, Mirza SK. Spinal-fusion surgery - the case for restraint. N Engl J Med 2004;350:722–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Waddell G. Low back pain: a twentieth century health care enigma. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1996;21:2820–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sackett DL, Rosenberg WM, Gray JA, et al. Evidence based medicine: what it is and what it isn't. BMJ 1996;312:71–2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Campbell C, Guy A. ‘Why can't they do anything for a simple back problem?’ A qualitative examination of expectations for low back pain treatment and outcome. J Health Psychol 2007;12:641–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.