Abstract

Background

Few studies have examined environmental, home and parental supports for physical activity in underserved adolescents (low income, ethnic minority). Given the increasing incidence of obesity in minority adolescents, it is important to better understand ecologic determinants of physical activity in these youth. This study used an ecologic model to evaluate the significance of neighborhood, home, and parental supports for physical activity on moderate-to-vigorous (MV) physical activity in underserved adolescents.

Design

The study was a secondary data analysis of a randomized controlled school-based trial “Active by Choice Today” (ACT) for increasing physical activity in underserved 6th graders. Schools were matched on school size, percentage minorities, percentage free or reduced-price lunch, and urban or rural setting prior to randomization. This study used a randomly selected sample of parents (n=280) from the intervention and control schools whose adolescent was enrolled in larger trial.

Setting/participants

A total of 679 6th-grade students (mean age, 11.4 years, 70% African-American, 76% free or reduced-price lunch, 52% female) participated in the larger trial. Parents of 280 youth were contacted to participate in a telephone survey and 198 (71%) took part in the study.

Interventions

The ACT trial was designed to test the efficacy of a 17-week (1 academic year) motivational plus behavioral skills intervention versus comparison after-school programs on increasing physical activity. A telephone survey was developed and administered within 6 months after the trial began on parents of 198 adolescents from the ACT randomized school-based trial during 2005–2007.

Main Outcome Measures

The primary outcome measure was adolescent MVPA based on 7-day accelerometry estimates from baseline to mid-intervention. The data were analyzed in 2010–2011 and included both parent and adolescent self-reports of environmental, home and family supports for physical activity.

Results

Regression analyses indicated a significant effect of parental and neighborhood supports for physical activity on adolescent MVPA. Adolescents who perceived higher (vs lower) levels of parental support for physical activity engaged in more minutes of MVPA (B = 3.01, SE = 1.38, p < .05) at mid-intervention. Adolescents who lived in neighborhoods with more (vs fewer) supports for physical activity (parks, lighting), also engaged in more minutes MVPA (B = 4.27, SE = 2.15, p < .05).

Conclusions

Support from parents and neighborhood quality are both associated with increased physical activity in underserved adolescents.

Introduction

The prevalence of childhood obesity has increased dramatically in the past 3 decades with 35% of adolescents and 40% of minority youth classified as overweight or obese nationally.1 It is estimated that less than one third of adolescents are sufficiently active to benefit their health and that this is attributed to increasingly sedentary lifestyles.2 The declining prevalence of physical activity may be attributable to the increasing prevalence of obesity and chronic disease in youth. 3 This study was designed to increase understanding of how parents, home, and the neighborhood environmental supports may influence physical activity in underserved adolescents (low income, ethnic minorities) as part of the “Active by Choice Today” (ACT) physical activity trial.4, 5

There is a growing interest in the application of ecologic models in understanding health behaviors such as physical activity.6, 7 An ecologic approach assumes that health is shaped by environmental subsystems including intrapersonal factors (individual characteristics), interpersonal processes and primary groups (formal and informal social networks), institutional factors (social institutions), community factors (neighborhood supports), and public policy. Recent studies go beyond the measurement of perceptions of neighborhood access and safety and include the direct measurement of neighborhood attributes related to physical activity 8-10. The ecologic framework in this study conceptualizes behavioral levels of influence at the neighborhood, home and parental levels related to understanding physical activity in underserved adolescents.

At the family level of the ecologic model, this study examined the impact of family social support on adolescent physical activity. Past studies have demonstrated that parental social support is an important factor associated with physical activity in youth11,12, 13,14. Biddle 13 demonstrated in a trial of multi-ethnic adolescents that vigorous physical activity was predicted by direct paths from adult encouragement. Prochaska and colleagues,12 showed that 12% of the variance in predicting accelerometer estimates of physical activity was accounted for by parent and peer support in a sample of multi-ethnic adolescents. Adkins et al.14 also found that tangible parental support was associated with greater physical activity in African-American girls.

At the home and neighborhood level of the ecologic model, this study examined parental perceptions of access and safety for home and neighborhood supports for physical activity. Few studies have focused on evaluating the relationship between home and neighborhood environmental supports for physical activity in adolescents 15, 16. In a study by Loureiro et al.,16 perceptions of unsafe neighborhoods and lack of access for leisure-time physical activity were associated with lower levels of physical activity among adolescents. Mota17 also reported that more-active children reported higher importance of having accessibility to neighborhoods with recreational facilities. In a qualitative study by Hume et al.,18 themes emerged with respect to physical activity including valuing the family home, opportunities for physical activity, green space and outside areas, the school and opportunities for social interaction.

The present study expanded on previous research by evaluating environmental supports for physical activity using an ecologic model that integrates neighborhood, home and parental supports for physical activity in underserved adolescents in the ACT trial. Little past research has examined environmental supports within the context of an ongoing intervention. In the present study a parental survey was developed to assess parenting styles and perceptions of social and environmental supports for physical activity in the home and neighborhood to determine if these factors would more strongly predict increases in physical activity in the intervention as compared to the control school adolescents.

Methods

Participants

The study was a secondary data analysis of a randomized controlled school-based trial “Active by Choice Today” (ACT) for increasing physical activity in underserved 6th graders. Schools were matched on school size, percentage minorities, percentage free or reduced-price lunch, and urban or rural setting prior to randomization. This study used a randomly selected sample of parents (n=280) from the intervention and control schools whose adolescent was enrolled in larger trial. 19 Parent and child participants lived in rural and urban areas of South Carolina and took part in the study during 2005–2007. Parents who were randomized to intervention or control conditions did not live within 50 miles of each other to reduce contamination effects. To be eligible, students had to (1) be enrolled in the 6th grade, (2) have parental consent, (3) agree to study participation and random assignment, and (4) be available for 6-month follow-up. A parent telephone survey was collected on 198 (104 girls and 94 boys) adolescent participants from the ACT trial for this study. Sixth-grade students were conceptualized as young adolescents given that early adolescence in the development literature includes this age range. 20

Procedure

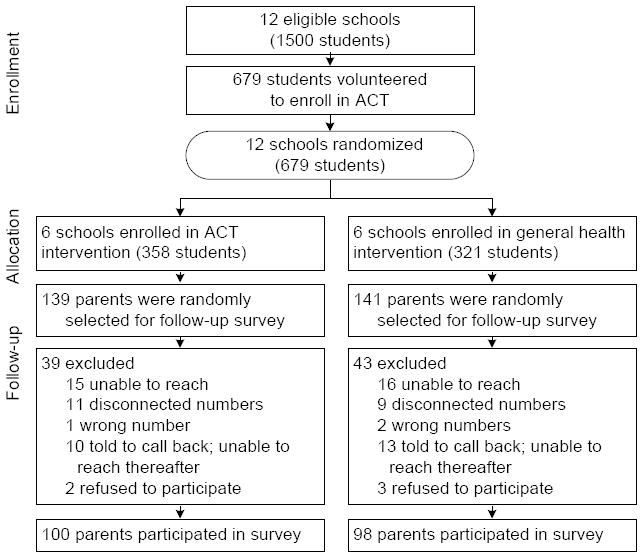

Within 6 months of the start of the trial, a random sample of parents (n=280) from intervention and control schools whose adolescent had recently completed the ACT trial after school program were selected using a random numbers table to participate in a telephone survey (see Figure 1 for randomization flowchart). Given that this supplement grant was not funded until after the larger ACT trial had begun adolescent participants had already begun their involvement in the afterschool programs prior to us contacting their parents. A letter describing the survey was sent to parents, and they were contacted by phone within 2 weeks. Parents were asked to participate in the telephone interview that was close in time to the baseline collection of their child’s involvement in the ACT trial. Of the parents sent a letter, 198 (71%) agreed to participate. The study was approved by the University of South Carolina IRB and informed consent/assent were obtained on both parents and youth. Parent participants received $10 after completing the survey.

Figure 1.

Randomization diagram

ACT, Active by Choice Today

Survey development

For the purposes of this supplement grant the key social environmental measures were based on tools that have been previously validated in minorities and that were theoretically relevant. An expert panel was formulated prior to the study onset to strategically select theoretically relevant and culturally validated measures. Eleven possible scales were selected for the expert review panel. Using the recommendations of the expert review panel, surveys were eliminated that did not target adults, did not fit the survey purpose, or had poor validity. Cognitive interviews (n=30 parents from the ACT trial) of the final set of questions were then conducted to assess comprehension and cultural relevance. Parents were contacted by phone for the cognitive interviews and verbal informed consent was obtained. Participant suggestions were used to revise the survey and resulted in minor wording modifications which included adding clarifying terms, reordering several questions, providing introductory statements, adding skip patterns, and adding response categories to several questions. Participants were given $5 for completing the cognitive interviews.

Measures

Child Items of Parental Support

Parental support was measured using a modified version of the Support for Exercise Scales developed by Sallis and colleagues.21 Adolescents responded to 6 items related to parent support. This scale has demonstrated internal consistency (α = .84) 21 and construct validity 22-24. Internal consistency in the current study was α = .83.

Parent Monitoring Items

A previously validated parent monitoring scale was used to measure monitoring of sedentary behaviors.25 Four items assessing level of agreement with limiting the amount of time their child watched TV, played videos games or used their computer during weekdays and weekend days were completed by parents. Items were averaged to create a measure of parental monitoring and showed good reliability in the present study (α = .80).

Parent Home and Neighborhood Items

Neighborhood environmental supports for physical activity were measured using 16 already validated items that assessed perceptions of social and physical environmental supports for physical activity. 26, 27 The neighborhood was defined as a 0.5-mile radius or 10-minute walk from respondent’s home. Items were averaged to create a measure of neighborhood support and showed moderate reliability in the present study (α = .68). Home support for physical activity was measured using 12 already validated items that assessed the availability of physical activity equipment in the home. 28 Participants reported whether or not various items and spaces were available in the home (e.g., basketball ring, exercise equipment such as treadmills, weight-lifting equipment, sports equipment, paved area outside the home, and covered or sheltered area outside the home). Items were summed to create a measure of home support and demonstrated moderate reliability in the present study (α = .68).

Body Mass Index

Height was measured with a Shorr Height Measuring Board and weight was measured with a SECA 880 digital scale (Germany) by certified measurement staff. Two measures of height and weight were collected and BMI was calculated as weight kg/height (meters2) averages. All equipment was calibrated before obtaining information on each adolescent.

Physical Activity Measure (Accelerometers)

Assessments of physical activity were obtained on adolescent participants with omni-directional estimates of actical accelerometers (Mini-Mitter, Bend, OR) at baseline and mid-intervention. Studies have demonstrated moderate to high correlations between actical estimates and activity counts and energy expenditure of individuals measured concurrently by other empirically tested accelerometers (MTI Actigraph, Caltrac, Tritrac).29 Participants wore an accelerometer over 7 consecutive days. Data were recorded in 1-minute epochs30 and 20 consecutive counts of zeros were used to indicate non-wear. Raw activity data were converted into time spent in moderate-to-vigorous (MV) physical activity (3 to <9 METS) based on actical activity count thresholds identified by Puyau and colleagues 29 where MVPA = 1,500 to <6,500 and VPA = ≥ 6,500.

Student’s data were considered missing for a given time period if they wore the accelerometer less than 80% of the time that 70% of the students wore their accelerometers.31 Approximately 3% of participants were missing all of their physical activity accelerometer data and an additional 34% had some missing data as a result of noncompliance. Missing data were dealt with using single imputation in the statistical package R 32 using the PAN package 33, which accounts for nested designs. Imputation procedures are described in greater detail elsewhere 34. Minutes of physical activity were summed for all days to provide one measure of average daily MVPA.

Data Analysis

Multilevel modeling was conducted to account for the non-independence in outcomes for youth within the same school. The model evaluated the effects of family, home and neighborhood variables on MVPA at mid-intervention. Based on previous studies 35 all analyses included the following covariates: baseline levels of MVPA, free and reduced-price lunch (an index of low-income status), gender, ethnicity, baseline BMI, parental education, and intervention condition. Primary variables were centered and the interaction terms were created using the centered variable.36

Using the notation of the mixed model 37, the statistical model is:

where MVPAmid is the realized value of MVPA at mid-intervention (8 weeks) into the intervention for individual j in the ith school, β0 is the intercept across all schools, β1 – β6 are the effects of covariates, and β7 is the increase in MVPA associated with a one-unit increase in family support holding the covariates constant, β8 is the increase in MVPA associated with a one-unit increase in parental monitoring holding the covariates constant, β9 is the increase in MVPA associated with a one-unit increase in home environment support holding the covariates constant, and β10 is the increase in MVPA associated with a one-unit increase in neighborhood support. The random effect bi allows for intercepts to differ among schools, thus accounting for any non-independence of the outcome within schools.

Intraclass correlation coefficients were calculated and showed approximately 5% (ICC = .05) of the variance in MVPA was due to clustering at the school level, supporting the utility of a multilevel statistical approach. The effects of the intervention were not significant (B = 4.24, se = 3.43, p > .05) in this supplement study, however intervention effects from the full ACT trial were significant at mid- but not post-intervention as previously reported.35 Therefore, intervention condition was included in the main statistical model as a covariate.

Results

Demographics and Baseline Characteristics

Demographic characteristics are depicted in Table 1. A significant difference was found for neighborhood support between intervention and control groups (p<0.05) with the intervention adolescent parents’ reporting higher levels of neighborhood support. Table 2 depicts the means and SDs of the home and environmental supports for physical activity across intervention versus control schools. There were no significant group differences.

Table 1.

Demographic and psychosocial characteristics

| Characteristic | Treatment | Control | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 100 | 98 | 198 |

| Boys | 50 (50.0%) | 44 (44.9%) | 94 (47.5%) |

| Girls | 50 (50.0%) | 54 (55.1%) | 104 (52.5%) |

| Age | 11.33 (0.62) | 11.50 (0.65) | 11.43 (0.67) |

| Ethnicity (% African-American) | 80 (80.0%) | 72 (73.5%) | 143 (70%) |

| Unadjusted BMI | 23.48 (6.40) | 24.19 (9.02) | 22.96 (6.08) |

| Waist Circ (cm) | 72.67 (12.52) | 70.99 (11.83) | 70.53 (12.22) |

| On Free or Reduced Luncha | 75 (75.10%) | 75 (76.53%) | 150 (76.14%) |

| MVPA (minutes/day) | 47.00 (2.04) | 48.08 (1.91) | 47.54 (1.97) |

| Relationship to Child | |||

| Mother | 87 (84.5%) | 79 (79.0%) | 166 (81.8%) |

| Father | 9 (8.7%) | 7 (7.0%) | 16 (7.9%) |

| Grandparent | 3 (2.9%) | 8 (8.0%) | 11 (5.4%) |

| Other | 4 (3.9%) | 6 (6.0%) | 10 (5.0%) |

| Relative’s Highest Education Level | |||

| Some high school | 12 (11.7%) | 7 (7.0%) | 19 (9.4%) |

| HS diploma | 28 (27.2%) | 24 (24.0%) | 52 (25.6%) |

| Some College | 27 (26.2%) | 42 (42.0%) | 69 (34.0%) |

| College Degree | 26 (25.2%) | 19 (19.0%) | 45 (22.2%) |

| Some Grad School | 3 (2.9%) | 2 (2.0%) | 5 (2.5%) |

| Grad School Degree | 7 (6.8%) | 6 (6.0%) | 13 (6.4%) |

| Relative’s Ethnicity (% black) | 88 (85.4%) | 74 (74.7%) | 162 (80.2%) |

| Marital Status | |||

| Married | 55 (53.4%) | 52 (52.0%) | 107 (52.7%) |

| Widowed/Divorced/Separated | 24 (23.3%) | 21 (21.0%) | 45 (22.2%) |

| Never Married | 24 (23.3%) | 27 (27.0%) | 51 (25.1%) |

| # of people in household | |||

| Two | 8 (7.8%) | 11 (11.0%) | 19 (9.5%) |

| Three | 18 (17.6%) | 21 (21.0%) | 39 (19.4%) |

| Four | 31 (30.4%) | 30 (30.0%) | 61 (30.3%) |

| Five | 23 (22.5%) | 20 (20.0%) | 43 (21.4%) |

| Six or more | 22 (21.6%) | 17 (17.0%) | 39 (19.4%) |

| # of children in household | |||

| One | 17 (16.7%) | 24 (24.0%) | 41 (20.3%) |

| Two | 32 (31.4%) | 39 (39.0%) | 71 (35.1%) |

| Three | 32 (31.4%) | 22 (22.0%) | 74 (26.7%) |

| Four | 12 (11.8%) | 7 (7.0%) | 19 (9.4%) |

| Five or more | 9 (8.8%) | 8 (8.0%) | 17 (8.4%) |

| Parental Support | 1.85 (.56) | 1.82 (.56) | 1.83 (.56) |

| Parent Monitoring | 3.08 (.80) | 3.13 (.83) | 3.11 (.82) |

| Home Environment | 17.94 (2.65) | 17.80 (2.62) | 17.87 (2.63) |

| Neighborhood* | 2.87 (.44) | 2.72 (.54) | 2.80 (.50) |

Notes: Values are expressed as M (SD) or count (%); There are no significant differences between treatment and control.

Percentages are calculated excluding missing data (1 missing in treatment, 0 missing in control).

p<0.05

Table 2.

Home and Environmental supports

| Variable | Treatment | Control | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 100 | 98 | 198 |

| Neighborhood Traffic | 3.05 (.74) | 2.89 (.86) | 2.97 (.80) |

| Neighborhood Crime | 3.28 (.67) | 3.17 (.68) | 3.23 (.67) |

| Neighborhood Social Norms | 3.40 (.71) | 3.33 (.86) | 3.37 (.78) |

| Neighborhood Supports for physical activity | 2.17 (.97) | 1.94 (.97) | 2.06 (.97) |

| Neighborhood Stray Dogs | 2.05 (1.22) | 2.10 (1.26) | 2.07 (1.24) |

| Home physical activity equipment | 1.57 (.24) | 1.55 (.26) | 1.56 (.25) |

| Home Infrastructure for physical activity | 1.92 (.32) | 1.90 (.30) | 1.91 (.31) |

Note: Values are expressed as M (SD) or count. Lower numbers in the “Neighborhood crime” scale indicate higher crime rates. There are no significant differences between treatment and control.

p<.05

To assess the degree to which the subsample of ACT participants used in the current study was different from the entire sample of ACT participants, analyses were run on age, BMI, waist circumference, gender, ethnicity and MVPA. A significant difference was found such that the subsample had slightly higher levels of baseline (t = −2.76 (332), p<.05) and mid-intervention MVPA (t = −2.76 (318), p<.05) MVPA. Indicating that the subsample engaged in only 4.4 and 3.9 more minutes of MVPA, respectively, as compared to the entire ACT sample.

Correlation Analyses

Correlation analyses (Table 3) showed MVPA at mid-intervention was negatively correlated with BMI and positively correlated with neighborhood environment.

Table 3.

Correlations between MVPA, BMI, family, and neighborhood variables

| Midpoint MVPA | Baseline MVPA | BMI | Parental support | Parent monitoring | Neighborhood | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Midpoint MVPA | — | |||||

| Baseline MVPA | 0.52* | — | ||||

| BMI | −0.15** | −0.14** | — | |||

| Parental support | 0.13*** | 0.03 | 0.12*** | — | ||

| Parent monitoring | 0.02 | −0.07 | −0.02 | 0.03 | — | |

| Home | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.07 | 0.12*** | — |

| Neighborhood | 0.14** | −0.01 | −0.02 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.05 |

p<0.01,

p<0.05,

p<0.10

MVPA, moderate-to-vigorous physical activity

Modeling Analyses

Results (Table 4) showed a significant effect for two covariates such that being a girl (p < .01) was associated with lower MVPA and having higher baseline MVPA were associated with higher MVPA at mid-intervention (p < .01). There was a significant effect of child-reported parental support such that adolescents who reported higher (vs lower) levels of parental support for physical activity engaged in greater minutes of MVPA (p < .05). A significant main effect for the neighborhood environment also demonstrated that neighborhoods with more supports for physical activity were associated with greater minutes of adolescent MVPA (p < .05).

Table 4.

Results of the multilevel model describing the relationship of environmental supports to MVPA (N=12, n=197).

| Fixed effects | Estimate | SE | t-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 48.95 | 4.33 | 11.32* |

| Bmi | −0.21 | 0.13 | −1.61 |

| Girl | −7.36 | 2.08 | −3.53** |

| Parent education | −0.59 | 0.87 | −0.67 |

| Black | −3.01 | 2.49 | −1.21 |

| Full-pay lunch | −1.27 | 2.57 | −0.49 |

| Baseline MVPA | 0.41 | 0.06 | 7.39** |

| Treatment | 3.96 | 3.38 | 1.17 |

| Parental support | 3.01 | 1.38 | 2.19* |

| Parent monitoring | 0.59 | 1.22 | 0.49 |

| Home environment | 0.12 | 0.40 | −0.31 |

| Neighborhood | 4.27 | 2.15 | 1.99* |

|

| |||

| Random effects | |||

|

| |||

| Within-school variance | 180.93 | ||

| Between-school variance | 20.53 | ||

Note:

p<.01;

p<.05;

df for treatment effects were constrained by the number of schools (N=12) in the analyses.

MVPA= moderate-to-vigorous physical activity

Analyses were conducted to test for free or reduced-price lunch effects as an additional Level-2 variable. Results showed no significant effect of free and reduced lunch at mid-intervention MVPA (B= −0.03, SD= 0.12, p> .05). Furthermore, results from the primary analyses remained although the neighborhood effect was reduced to a trend (B=4.05, SD= 2.15, t= 1.88, p < .10). The effect size was similar to that of the model without the Level-2 free and reduced-price lunch although this study was not powered to detect Level-2 effects 38.

Discussion

The results of this study demonstrated the importance of parent and neighborhood levels of support for physical activity in underserved adolescents. Parental and neighborhood supports for physical activity were significant predictors of physical activity in adolescents who participated in the ACT trial. In addition, physical activity was negatively correlated with being female and with higher BMI in this study consistent with previous studies. Interestingly, there were no significant effects for physical activity supports related to the adolescents’ home environment. These findings expand on previous studies in important ways by demonstrating the critical role of perceptions of the neighborhood environment and parent support as determinants of physical activity in underserved adolescents.

Consistent with previous research this study showed the important role that parents have in supporting their youth to engage in physical activity. Although some of the previous studies have shown mixed support for the role of social support, 12, 39-42 this study showed that higher levels of youth-reported parental support were associated with an increase in MVPA at mid-intervention. Although equal numbers of studies have shown positive or null effects of parental support, few have focused primarily on underserved adolescents. Consistent with the Adkins’ study 14 in African American adolescent girls, this study showed positive and moderately strong relationships in ethnic minority adolescents. These findings suggest that parents may need to be more than just active role models if their child is to have a physically active lifestyle 43.

This is one of the first studies to evaluate home and neighborhood support using an ecologic approach for understanding underserved adolescent youth physical activity. It is interesting that neighborhood supports were significantly related to adolescent physical activity but home supports were not. An accumulating amount of evidence is building that suggests that environmental supports related to access and safety for physical activity are major factors related to understanding patterns of physical activity in youth.43-47 This study further demonstrates the importance of addressing parental perceptions of safety and access for physical activity at the neighborhood level beyond the home setting. These findings have important implications for developing policy for under-resourced neighborhoods that may not have safe places for physical activity.

There are several limitations to this study. One limitation was that only a subset of parents in ACT was recruited to participate in the survey. Given the scope of this supplement project, it was not feasible to collect data on the full trial sample of parents. Because sample size of this study was limited, there was not a sufficient number of schools to test for Level-2 effects 38. Although the effect sizes in this study were modest, they were consistent with previous research using physical activity accelerometer estimates 35, 48, 49. Further research is needed to replicate these finding in larger studies, across a greater variety of ethnic minorities.

In summary, findings from this study support an ecologic understanding of physical activity in low-income African-American adolescents. This ecologic approach indicated that neighborhood and parent supports for physical activity are important to consider in low-income communities that may lack resources for promoting physical activity in youth. The role of parents will continue to be an important focus for physical activity intervention trials in underserved adolescents.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by a Minority Supplement Grant (R01 HD045693-03S1) and by the parent grant (R01 HD045693) funded by the National Institutes of Child Health and Human Development to Dawn K. Wilson, PhD.

Footnotes

No financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, Lamb MM, Flegal KM. Prevalence of High Body Mass Index in U.S. Children and Adolescents, 2007–2008. JAMA: Journal of the American Medical Association. 2010;303(3):242–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Taylor WC, Beech BM, Cummings SS, Wilson DK, Rodrigue JR. Increasing physical activity levels among youth: A public health challenge. Health-promoting and health-compromising behaviors among minority adolescents. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1997. pp. 107–28. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Must A, Strauss RS. International Journal of Obesity & Related Metabolic Disorders. Nature Publishing Group; 1999. Risks and consequences of childhood and adolescent obesity; p. s2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilson DK, Kitzman-Ulrich H, Jelalian E, Steele RG. Handbook of childhood and adolescent obesity. New York, NY: Springer Science + Business Media; 2008. Cultural considerations in the development of pediatric weight management interventions; pp. 293–310. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wilson DK, Griffin S, Saunders RP, Kitzman-Ulrich H, Meyers DC, Mansard L. Using process evaluation for program improvement in dose, fidelity and reach: The ACT trial experience. The International Journal Of Behavioral Nutrition And Physical Activity. 2009:6. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-6-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sallis JF, Owen N, Fisher EB, Glanz K, Rimer BK, Viswanath K. Health behavior and health education: Theory, research, and practice. 4. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2008. Ecological models of health behavior; pp. 465–85. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bronfenbrenner U. Contexts of child rearing: Problems and prospects. Am Psychol. 1979;34(10):844–50. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Giles-Corti B, Donovan RJ. The relative influence of individual, social and physical environment determinants of physical activity. Soc Sci Med. 2002;54(12):1793–812. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00150-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Giles-Corti B, Donovan RJ. Socioeconomic Status Differences in Recreational Physical Activity Levels and Real and Perceived Access to a Supportive Physical Environment. Prev Med. 2002;35(6):601–11. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2002.1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sallis JF, Saelens BE, Frank LD, Conway TL, Slymen DJ, Cain KL, et al. Neighborhood built environment and income: Examining multiple health outcomes. Social Science & Medicine. 2009;68(7):1285–93. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sallis JF, Prochaska JJ, Taylor WC. A review of correlates of physical activity of children and adolescents. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2000;32(5):963–75. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200005000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Prochaska JJ, Rodgers MW, Sallis JF. Association of Parent and Peer Support With Adolescent Physical Activity. Research Quarterly for Exercise & Sport. 2002;73(2):206. doi: 10.1080/02701367.2002.10609010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Biddle S, Goudas M. Analysis of children’s physical activity and its. J Sch Health. 1996;66(2):75. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.1996.tb07914.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adkins S, Sherwood NE, Story M, Davis M. Physical activity among African-American girls: the role of parents and the home environment. Obes Res. 2004;12(Suppl):38S–45S. doi: 10.1038/oby.2004.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boone-Heinonen J, B Do active communities support activity, or support active people? residential self-selection in the estimation of built environment influences on physical activity. U S : ProQuest Information & Learning. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Loureiro N, Matos MG, Santos MM, Mota J, Diniz JA. Neighborhood and physical activities of Portuguese adolescents. The International Journal Of Behavioral Nutrition And Physical Activity. 2010;7:33. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-7-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mota J, Silva P, Santos MP, Ribeiro JC, Oliveira J, Duarte JA. Physical activity and school recess time: Differences between the sexes and the relationship between children’s playground physical activity and habitual physical activity. J Sports Sci. 2005;23(3):269–75. doi: 10.1080/02640410410001730124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hume C, Salmon J, Ball K. Children’s perceptions of their home and neighborhood environments, and their association with objectively measured physical activity: a qualitative and quantitative study. Health Educ Res. 2005 February 1;20(1):1–13. doi: 10.1093/her/cyg095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wilson DK, Kitzman-Ulrich H, Williams JE, Saunders R, Griffin S, Pate R, et al. An overview of “The Active by Choice Today” (ACT) trial for increasing physical activity. Contemp Clin Trials. 2008;29(1):21–31. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2007.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wilson DK, St George SM, Zarrett N. Developmental Influences in Understanding Children and Adolescent Health Behaviors. In: Suls J, D K, Kaplan R, editors. Handbook of Health Psychology. Guildford press; 2010. pp. 133–46. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sallis JF, Grossman RM, Pinski RB, Patterson TL, Nader PR. The development of scales to measure social support for diet and exercise behaviors. Prev Med. 1987;16(6):825–36. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(87)90022-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sallis JF, Alcaraz JE, McKenzie TL, Hovell MF. Predictors of change in children’s physical activity over 20 months: Variations by gender and level of adiposity. Am J Prev Med. 1999;16(3):222–9. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(98)00154-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kitzman-Ulrich H, Wilson DK, Van Horn ML, Lawman HG. Differences in self-efficacy, social support, and physical activity by sex and body mass index in underserved youth. Health Psychol. doi: 10.1037/a0020853. under review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sallis JF, Patterson TL, Buono MJ, Atkins CJ, Nader PR. Aggregation of physical activity habits in Mexican-American and Anglo families. J Behav Med. 1988;11(1):31–41. doi: 10.1007/BF00846167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arredondo EM, Elder JP, Ayala GX, Campbell N, Baquero B, Duerksen S. Is parenting style related to children’s healthy eating and physical activity in Latino families? Health Educ Res. 2006;21(6):862–71. doi: 10.1093/her/cyl110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cerin E, Saelens BE, Sallis JF, Frank LD. Neighborhood Environment Walkability Scale: Validity and Development of a Short Form. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 2006;38(9):1682–91. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000227639.83607.4d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sallis JF, Johnson MF. Assessing perceived physical environmental variables that may influence physical activity. Research Quarterly for Exercise & Sport. 1997;68(4):345. doi: 10.1080/02701367.1997.10608015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hume C, Ball K, Salmon J. Development and reliability of a self-report questionnaire to examine children’s perceptions of the physical activity environment at home and in the neighborhood. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2006;3(16) doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-3-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Puyau MR, Adolph AL, Vohra FA, Zakeri I, Butte NF. Prediction of activity energy expenditure using accelerometers in children. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2004;36(9):1625–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Welk GJ, Schaben JA, Morrow JR., Jr Reliability of accelerometry-based activity monitors: a generalizability study. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2004;36(9):1637–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Catellier DJ, Hannan PJ, Murray DM, Addy CL, Conway TL, Song Y, et al. Imputation of Missing Data When Measuring Physical Activity by Accelerometry. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 2005;37:S555–S62. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000185651.59486.4e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.R Development Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. 2.10.1. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schafer JL. PAN: Multiple imputation for multivariate panel data, software library written for S-PLUS. 1997 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Van Horn ML, Lawman HG. A Report on Missing Data in the Active by Choice Today (ACT) Trial. 2010 Available from: http://www.psych.sc.edu/PDFDocs/Final%20ACT.pdf.

- 35.Wilson DK, Horn MLV, Kitzman-Ulrich H, Saunders R, Pate R, Lawman HG, et al. Increasing Physical Activity in Low Income and Minority Adolescents. Health Psychol. doi: 10.1037/a0023390. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stanhope KL, Schwarz JM, eim NL, Griffen SC, Bremer AA, Graham JL, et al. Consuming fructose-sweetened, not glucose-sweetened, beverages increases visceral adiposity and lipids and decreases insulin sensitivity in overweight/obese humans. J Clin Invest. 2009;119(5):1322–34. doi: 10.1172/JCI37385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maas CJM, Hox JJ. Sufficient sample sizes for multilevel modeling. Methodology. 2005;1(3):86–92. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Beets MW, Pitetti KH, Forlaw L. The Role of Self-efficacy and Referent Specific Social Support in Promoting Rural Adolescent Girls’ Physical Activity. Am J Health Behav. 2007;31(3):227–37. doi: 10.5555/ajhb.2007.31.3.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sallis JF, Prochaska JJ, Taylor WC, Hill JO, Geraci JC. Correlates of physical activity in a national sample of girls and boys in Grades 4 through 12. Health Psychol. 1999;18(4):410–5. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.18.4.410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wu T-Y, Pender N, Noureddine S. Gender Differences in the Psychosocial and Cognitive Correlates of Physical Activity Among Taiwanese Adolescents: A Structural Equation Modeling Approach. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2003;10(2):93–105. doi: 10.1207/s15327558ijbm1002_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ward DS, Dowda M, Trost SG, Felton GM, Dishman RK, Pate RR. Physical Activity Correlates in Adolescent Girls Who Differ by Weight Status. Obes Res. 2006;14(1):97–105. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ferreira I, van der Horst K, Wendel-Vos W, Kremers S, van Lenthe FJ, Brug J. Environmental correlates of physical activity in youth -- A review and update. Obes Rev. 2007;8(2):129–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2006.00264.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kligerman M, Sallis JF, Ryan S, Frank LD, Nader PR. Association of neighborhood design and recreation environment variables with physical activity and body mass index in adolescents. Am J Health Promot. 2007;21(4):274–7. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-21.4.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cohen DA, Ashwood S, Scott M, Overton A, Evenson KR, Voorhees CC, et al. Proximity to School and Physical Activity Among Middle School Girls: The Trial of Activity for Adolescent Girls Study. Journal of Physical Activity & Health. 2006;3:S129–s38. doi: 10.1123/jpah.3.s1.s129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Motl RW, Dishman RK, Saunders RP, Dowda M, Pate RR. Perceptions of Physical and Social Environment Variables and Self-Efficacy as Correlates of Self-Reported Physical Activity Among Adolescent Girls. J Pediatr Psychol. 2007;32(1):6–12. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsl001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Saksvig BI, Catellier DJ, Pfeiffer KA, Schmitz KH, Conway TL, Going SB, et al. Travel by walking before and after school and physical activity among adolescent girls. Archives Of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 2007;161(2):153–8. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.161.2.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Adkins S, Sherwood NE, Story M, Davis M. Physical activity among African-American girls: the role of parents and the home environment. Obes Res. 2004;12:38S–45S. doi: 10.1038/oby.2004.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ries AV, Voorhees CC, Roche KM, Gittelsohn J, Yan AF, Astone NM. A quantitative examination of park characteristics related to park use and physical activity among urban youth. J Adolesc Health. 2009;45(3,Suppl):S64–S70. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]