Abstract

Aneuploidy decreases cellular fitness, yet it is also associated with cancer, a disease of enhanced proliferative capacity. To investigate one mechanism by which aneuploidy could contribute to tumorigenesis, we examined the effects of aneuploidy on genomic stability. We analyzed 13 budding yeast strains that carry extra copies of single chromosomes and found that all aneuploid strains exhibited one or more forms of genomic instability. Most strains displayed increased chromosome loss and mitotic recombination, as well as defective DNA damage repair. Aneuploid fission yeast strains also exhibited defects in mitotic recombination. Aneuploidy-induced genomic instability could facilitate the development of genetic alterations that drive malignant growth in cancer.

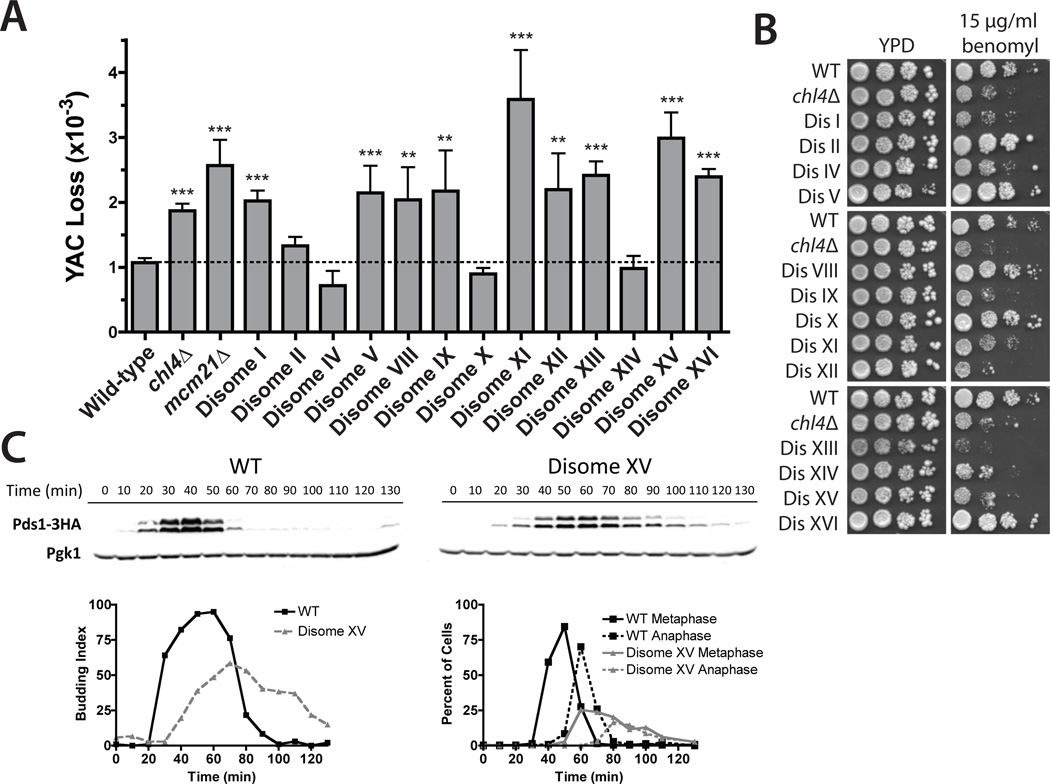

Whole-chromosome aneuploidy—or a karyotype that is not a multiple of the haploid complement—is found in greater than 90% of human tumors and may contribute to cancer development (1, 2). It has been suggested that aneuploidy increases genomic instability, which could accelerate the acquisition of growth-promoting genetic alterations (1, 3). However, whereas aneuploidy is a result of genomic instability, there is at present limited evidence as to whether genomic instability can be a consequence of aneuploidy itself. To test this possibility directly, we assayed chromosome segregation fidelity in 13 haploid strains of Saccharomyces cerevisiae that carry additional copies of single yeast chromosomes (4). These aneuploid strains (henceforth disomes) display impaired proliferation and sensitivity to conditions that interfere with protein homeostasis (4, 5). We measured the segregation fidelity of a yeast artificial chromosome (YAC) containing human DNA and found that the rate of chromosome missegregation was increased in 9 out of 13 disomic strains relative to a euploid control (Fig. 1A). The increase ranged from 1.7-fold to 3.3-fold, comparable to the fold increase observed in strains lacking the kinetochore components Chl4 or Mcm21. Consistent with chromosome segregation defects, 8 out of 13 disomic strains displayed impaired proliferation on plates containing the microtubule poison benomyl, including a majority of the strains that had increased rates of YAC loss (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

Aneuploidy induces chromosome missegregation. (A) YAC loss is increased in disomes and kinetochore mutants. The means ± SD of at least 12 cultures are displayed. **P < 0.005; ***P < 0.0005 (Student’s t test). (B) Proliferation of disomes is decreased in the presence of benomyl. 10-fold serial dilutions of the indicated strains are shown. (C) Pds1 levels and cell cycle progression in wild-type and disome XV cells after release from a G1 arrest (7).

Chromosome missegregation can result from defects in chromosome attachment to the mitotic spindle or from problems in DNA replication or repair. Defects in any of these processes delay mitosis by stabilizing the anaphase inhibitor Pds1 (securin) (6). Five out of five disomes (disomes V, VIII, XI, XV, and XVI) exhibited delayed degradation of Pds1 relative to wild type after release from a pheromone-induced G1 arrest (Fig. 1C and fig. S1). Defective chromosome bi-orientation delays anaphase through the mitotic checkpoint component Mad2 (6). Deletion of MAD2 had no effect on Pds1 persistence in four disomes, but eliminated this persistence in disome V cells (fig. S1). Disome V also delayed Pds1 degradation after release from a mitotic arrest induced by the microtubule poison nocodazole, which demonstrated that this strain exhibits a bi-orientation defect. Disome XVI, which displayed Mad2-independent stabilization of Pds1, recovered from nocodazole with wild-type kinetics (fig. S2). Thus, Pds1 persistence results predominantly from Mad2-independent defects in genome replication and/or repair (see below).

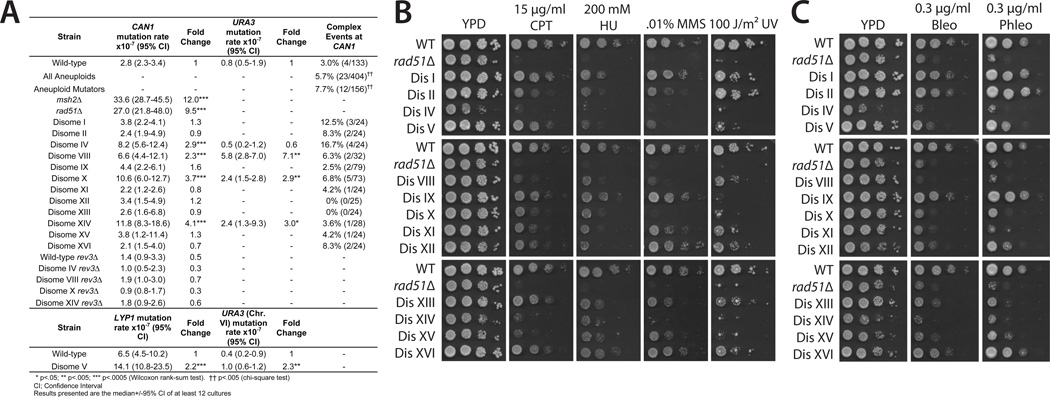

We next investigated whether aneuploidy could affect the rate of forward mutation. Disomes V, VIII, X, and XIV displayed an increased mutation rate at two independent loci, whereas disome IV displayed an increased mutation rate at CAN1 but not at URA3 (Fig. 2A). The fold increase ranged from 2.2-fold to 7.1-fold, less than the 9.5-fold and 12-fold increases observed in a recombination-deficient rad51Δ mutant and a mismatch repair–deficient msh2Δ mutant, respectively. Additionally, in an assay for microsatellite instability, we found that disomes VIII and XVI displayed increased instability in a poly(GT) tract (fig. S3), which demonstrated that aneuploidy can enhance both simple sequence instability and forward mutagenesis.

Fig. 2.

Aneuploidy increases the mutation rate and sensitivity to genotoxins. (A) Mutation rate in disomic strains. Note that the CAN1 and URA3 reporters are located on chromosome V; we therefore measured the mutation rate of disome V at LYP1 and of URA3 integrated on chromosome VI (7). (B) Tenfold serial dilutions of the indicated strains were spotted on medium supplemented or treated with a genotoxic agent. CPT, camptothecin; HU, hydroxyurea; MMS, methyl methanesulfonate. (C) Tenfold serial dilutions of cells on medium containing phleomycin (Phleo) or bleomycin (Bleo).

To define the mechanism underlying the increased mutation rate in aneuploid cells, we sequenced CAN1 alleles from 133 wild-type and 404 disomic isolates (7). The overall spectrum of spontaneous mutation was similar, with euploid and aneuploid cells displaying equivalent frequencies of base pair substitutions, frameshifts, transitions, and transversions (table S1). However, two significant differences were noted. First, the identity of base pairs gained and lost in the disomes differed relative to those seen in wild type in a largely strand-specific manner (tables S2, S3, and S4) (7). Second, disomes exhibited a twofold increase in the frequency of complex events relative to wild type (P < 0.002, chi-square test) (Fig. 2A). Complex events, i.e., multiple substitutions and/or frameshifts within a 5– to 10–base pair (bp) window, are caused by the translesion polymerase Polζ (8). The frequency of complex events was increased when sequences from all mutator strains (disomes IV, VIII, X, and XIV) were combined, but not when only nonmutator strains were examined. Deletion of REV3, which encodes the catalytic subunit of Polζ, abolished the increased mutation rate in the disomes (Fig. 2A), which showed that aneuploidy-induced mutagenesis is due to translesion polymerase activity.

The mutator phenotype and frequent appearance of complex events suggested that aneuploidy interferes with the repair of genomic damage. To test this, we examined the sensitivity of the disomes to genotoxic stress (Fig. 2B). A majority of disomes displayed impaired proliferation when treated with replication inhibitors (camptothecin or hydroxyurea) or DNA-damaging agents (methyl methanesulfonate or ultraviolet light). Aneuploid strains derived by triploid meiosis also displayed striking sensitivities to genotoxic drugs [fig. S4 and (9)]. We next assessed the role of Polζ in lesion bypass. In wild-type yeast, loss of REV3 confers only a slight increase in genotoxin sensitivity, as recombinational repair is sufficient to replicate past most lesions (10). Seven out of nine disomes displayed enhanced sensitivity to genotoxins in the absence of REV3, which suggested that recombinational repair is defective in the disomes (fig. S5). We therefore assayed the sensitivity of the disomes to phleomycin and bleomycin, two double-strand break (DSB)–inducing drugs, which create lesions that are repaired by homologous recombination (11). Nine out of 13 disomes were sensitive to both drugs, and disomes IV, VIII, X, XI, and XIV displayed an approximately 100- to 1000-fold increase in sensitivity relative to wild type (Fig. 2C).

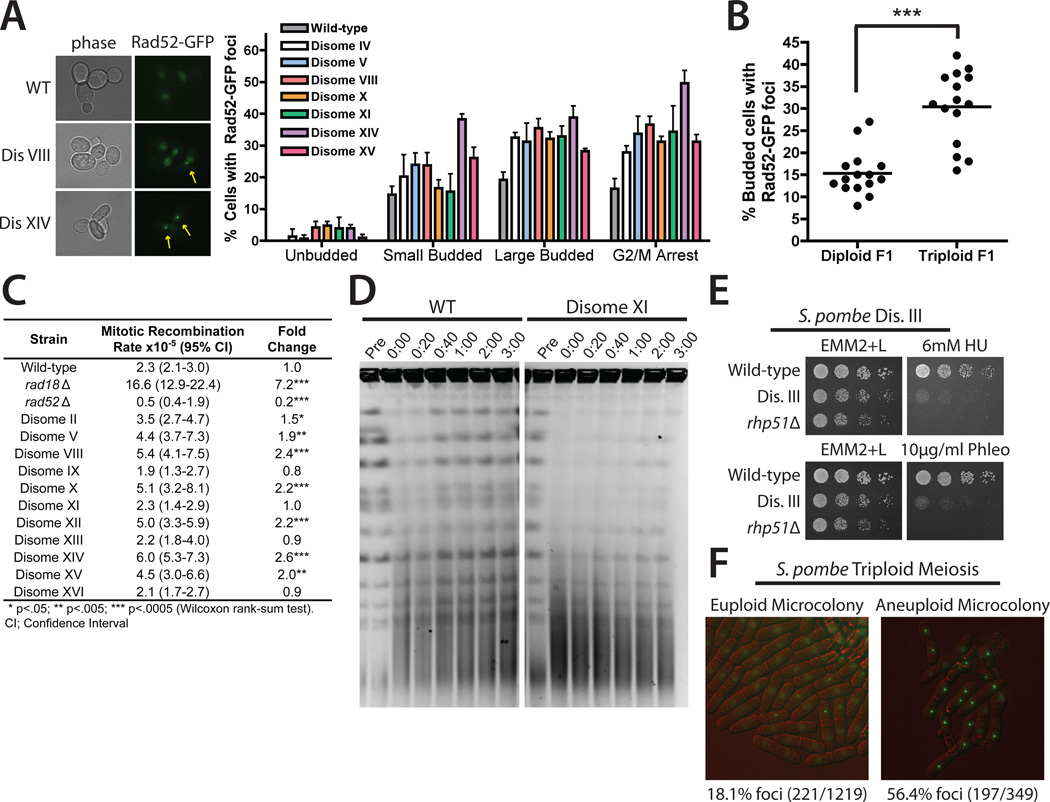

To further investigate the effects of aneuploidy on recombination, we quantified the fraction of cells that contained DSBs in seven phleomycin-sensitive disomes by monitoring Rad52–green fluorescent protein (Rad52-GFP) foci, which localize to sites of recombinational repair (12). After release from a pheromone-induced G1 arrest, all seven disomes displayed an increased frequency of Rad52-GFP foci in large-budded cells (corresponding to late S phase or G2). Disomes arrested with nocodazole also exhibited increased numbers of Rad52-GFP foci (Fig. 3A). The aneuploid meiotic progeny of a triploid strain displayed Rad52-GFP foci more frequently than euploid spores did, which demonstrated that the appearance of recombination foci is a common consequence of aneuploidy in yeast (Fig. 3B). Consistent with an aneuploidy-induced increase in DSB formation and/or defective DSB repair, 7 out of 11 disomes also displayed an increased rate of spontaneous mitotic recombination between direct tandem repeats (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3.

Aneuploidy induces recombination defects. (A) The fraction of wild-type and disomic cells displaying Rad52-GFP foci after release from a G1 arrest or arrested with nocodazole. Images display wild-type, disome VIII, and disome XIV cells arrested with nocodazole. Means ± SD of three experiments are shown. (B) Rad52-GFP foci were scored in spores from triploid or diploid strains (7). The mean (black bar) of 15 spore-derived colonies (dots) are displayed. ***P < 0.0005 (Student’s t test). (C) Mitotic recombination between truncated alleles of ade2 (7). (D) Wild-type and disome XI cells treated with phleomycin were released into medium containing nocodazole. Chromosome integrity was analyzed by pulse-field gel electrophoresis (7). (E) Fivefold serial dilutions of fission yeast cells on medium supplemented with hydroxyurea or phleomycin. Rhp51 is the fission yeast Rad51 homolog. (F) The fraction of cells displaying SpRad22-GFP foci in aneuploid and euploid microcolonies resulting from sporulation of a triploid strain. Images are representative euploid and aneuploid microcolonies.

To test whether disomes form more DSBs during DNA replication, we created rad52Δ strains, in which a single DSB is sufficient to block cell division (13). Small-budded RAD52 and rad52Δ cells were isolated via micromanipulation, and their proliferation was monitored (7). Six percent of rad52Δ cells arrested with large buds, whereas in four out of six rad52Δ disomes this percentage was significantly increased (fig. S6). Thus, some aneuploid strains accumulate an increased number of DSBs during DNA replication. However, the large-budded arrest in disome V may be due to defective chromosome bi-orientation, as frequent arrest was also observed in RAD52 disome V cells (fig. S6).

Is DNA repair also compromised in aneuploid cells? To test this, we examined Rad52-GFP foci dynamics in disomes treated with phleomycin. In the presence of phleomycin, euploid and aneuploid strains arrested as large-budded cells and formed Rad52-GFP foci. After phleomycin removal, euploid cells resolved their Rad52-GFP foci and resumed budding, whereas seven out of seven disomic strains remained arrested and displayed persistent Rad52-GFP foci (fig. S7). The sensitivity to phleomycin was not caused by DNA damage checkpoint defects, as exposure to phleomycin induced a prolonged cell cycle arrest (fig. S7) and caused hyperphosphorylation of Rad53, a marker of checkpoint activation (fig. S8). Instead, disomes appear to be defective in DNA repair. When chromosomes were visualized by pulse-field gel electrophoresis, phleomycin treatment resulted in chromosome fragmentation in both aneuploid and euploid cells (Fig. 3D and fig. S9). After phleomycin removal, intact chromosomes quickly reappeared in a wild-type strain (Fig. 3D and fig. S9). In contrast, a significant delay in chromosome recovery was apparent in disomes V, VIII, XI, and XIII (Fig. 3D and fig. S9). Disome II, which does not lose viability on plates containing phleomycin (Fig. 2C), exhibited chromosome repair kinetics similar to those of wild-type cells (fig. S9). Low doses of ionizing radiation (IR) had a similar, although less severe, effect on the disomes as phleomycin. Disomes lost viability upon treatment with IR, though several strains were able to resolve a subset of IR-induced Rad52-GFP foci (fig. S10). The different effects of phleomycin and IR may indicate that these treatments cause partially distinct forms of DNA damage or that disomic chromatin is particularly vulnerable to phleomycin-induced lesions. Taken together, our results indicate that multiple aneuploids exhibit wide-ranging defects in recombination and DNA repair.

We also investigated the effects of aneuploidy on genomic stability in fission yeast. Fission yeast disome III, the only viable disome (14), displayed increased sensitivity to hydroxyurea and phleomycin relative to a euploid strain (Fig. 3E). Additionally, Rad22 foci (fission yeast Rad52) (15, 16) were present in 18% of euploid cells and 56% of aneuploid cells resulting from sporulation of a triploid strain (Fig. 3F). Time-lapse photomicroscopy revealed that approximately equal numbers of euploid and aneuploid cells formed SpRad22 foci per cell division (fig. S11). However, Rad22 foci persisted on average five times as long in aneuploid cells as in euploid cells. We conclude that in fission yeast, aneuploidy impairs DNA damage resistance and mitotic recombination.

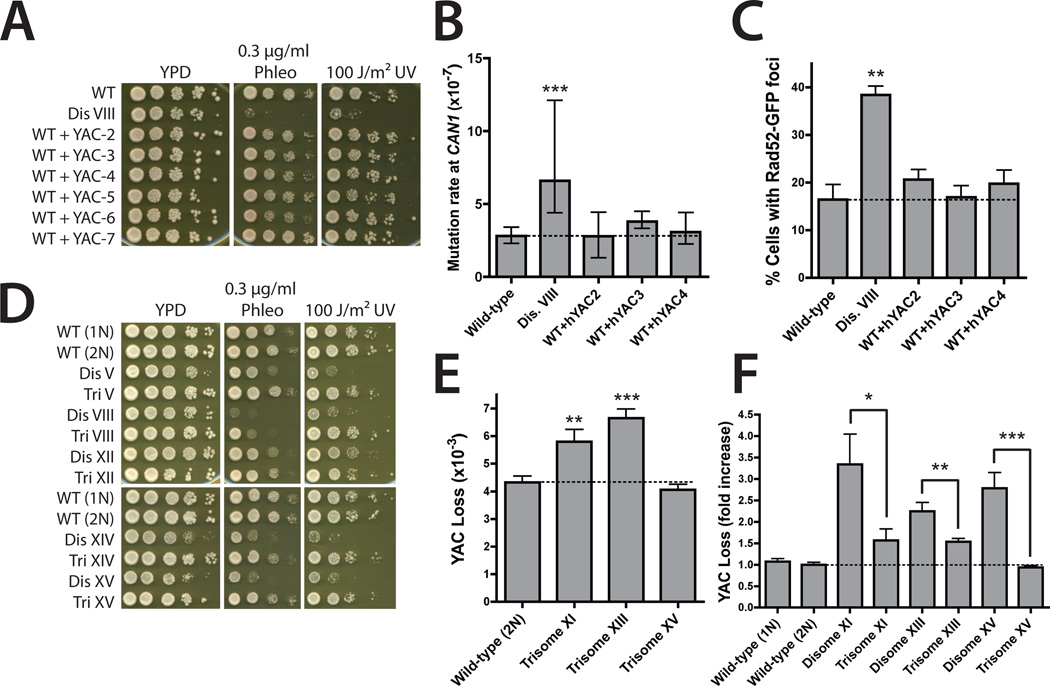

We next determined whether the genomic instability present in the disomic strains was caused by the presence of extra DNA or by aneuploidy-induced imbalances in protein stoichiometry. Yeast strains carrying YACs harboring human DNA were not sensitive to genotoxic agents and did not display increased mutation or Rad52-GFP foci, which demonstrated that replication of an extra chromosome is not sufficient to induce genomic instability (Fig. 4, A to C). If the defects in damage repair were caused by stoichiometric imbalances in yeast proteins, then the effects should be mitigated in diploids carrying single extra chromosomes (henceforth, trisomes) (4). Indeed, five out of five trisomes were more resistant to genotoxic damage than their isogenic disomes, and in three out of three trisomes the fold increase in YAC loss relative to a diploid strain was less than the fold increase observed in isogenic disomes (Fig. 4, D to F). Thus, excess protein, but not excess DNA, causes genomic instability in aneuploid cells.

Fig. 4.

Stoichiometric imbalances drive genomic instability. (A) Tenfold serial dilutions of strains harboring YACs on the indicated media. (B) The mutation rate at CAN1. Median and 95% confidence intervals of at least 12 independent cultures are shown. ***P < 0.0005 (Wilcoxon rank-sum test). (C) Fraction of nocodazole-arrested cells displaying Rad52-GFP foci. Means ± SD of three experiments are shown. **P < 0.005 (Student’s t test ). (D) Tenfold serial dilutions of trisomic and corresponding disomic strains on the indicated medium. (E) YAC loss rates in diploid and trisomic strains. Means ± SD of at least 12 independent cultures are shown. (F) YAC loss rates normalized to either haploid or diploid controls. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.005; ***P < 0.0005 (Student’s t test).

This study establishes that missegregation of a single chromosome is sufficient to induce the hallmarks of genomic instability, including whole-chromosome instability, mutagenesis, and sensitivity to genotoxic stress (summarized intable S5). Genomic instability in the disomes is not correlated with the size of the extra chromosome or the delay in cell cycle progression (fig. S12). Aneuploidy-induced genomic instability may result from imbalances in particular genes and/or from proteotoxic stress caused by aneuploidy (7). Aneuploid strains derived from triploid meiosis were also shown to be unstable (17) but a recent report described the construction of stable aneuploid strains using this method (9). We note that 87.5% of the spores derived from triploid meiosis in the latter study were discarded due to karyotypic instability. Moreover, CGH analysis of the aneuploid strains characterized in (9) demonstrates that many have heterogenous karyotypes (figs. S13 and S14), consistent with our finding that the vast majority (but, potentially, not all) aneuploid strains display chromosomal instability. In mammals, cells derived from individuals with Down syndrome (trisomy 21) are also sensitive to DNA-damaging agents (18), and aneuploid karyotypes have been correlated with chromosomal instability in transformed Chinese hamster embryo cells (19) and in p53−/− colon cancer cells (20). Thus, some degree of aneuploidy-induced genomic instability may be conserved among eukaryotes.

Genomic instability provides a growth advantage during the experimental evolution of microorganisms and drives the development of tumors (21–23). Although aneuploidy confers severe disadvantages to cells by stressing protein homeostasis and altering metabolism (4, 5, 24), our results suggest it may also benefit cells under selective pressure by increasing the likelihood that growth-promoting genetic alterations will develop. The mutagenic effects of aneuploidy that we report here may represent one mechanism by which changes in karyotype influence cancer development and evolution.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank D. Koshland, T. Petes, R. Li, L. Symington, D. Page, T. Matsumoto, and J. Takeda for reagents, and I. Cheeseman, J. Haber, M. Rose, F. Solomon, and the Amon lab for comments on the manuscript. J.M.S. and S.J.P. are supported by NSF Graduate Fellowships and A. A by grant GM056800. A.A. is an HHMI investigator.

References and Notes

- 1.Torres EM, Williams BR, Amon A. Aneuploidy: Cells losing their balance. Genetics. 2008;179:737. doi: 10.1534/genetics.108.090878. Medline. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weaver BA, Cleveland DW. Does aneuploidy cause cancer? Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2006;18:658. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2006.10.002. Medline. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matzke MA, Mette MF, Kanno T, Matzke AJM. Does the intrinsic instability of aneuploid genomes have a causal role in cancer? Trends Genet. 2003;19:253. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(03)00057-x. Medline. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Torres EM, et al. Effects of aneuploidy on cellular physiology and cell division in haploid yeast. Science. 2007;317:916. doi: 10.1126/science.1142210. Medline. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Torres EM, et al. Identification of aneuploidy-tolerating mutations. Cell. 2010;143:71. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.08.038. Medline. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Musacchio A, Salmon ED. The spindle-assembly checkpoint in space and time. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007;8:379. doi: 10.1038/nrm2163. Medline. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Materials and methods are available as supporting material on Science Online.

- 8.Harfe BD, Jinks-Robertson S. DNA polymerase zeta introduces multiple mutations when bypassing spontaneous DNA damage in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. 2000;6:1491. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00145-3. Medline. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pavelka N, et al. Aneuploidy confers quantitative proteome changes and phenotypic variation in budding yeast. Nature. 2010;468:321. doi: 10.1038/nature09529. Medline. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rattray AJ, Shafer BK, McGill CB, Strathern JN. The roles of REV3 and RAD57 in double-strand-break-repair-induced mutagenesis of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 2002;162:1063. doi: 10.1093/genetics/162.3.1063. Medline. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen J, Stubbe J. Bleomycins: Towards better therapeutics. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2005;5:102. doi: 10.1038/nrc1547. Medline. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lisby M, Rothstein R, Mortensen UH. Rad52 forms DNA repair and recombination centers during S phase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2001;98:8276. doi: 10.1073/pnas.121006298. Medline. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pâques F, Haber JE. Multiple pathways of recombination induced by double-strand breaks in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 1999;63:349. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.63.2.349-404.1999. Medline. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Niwa O, Tange Y, Kurabayashi A. Growth arrest and chromosome instability in aneuploid yeast. Yeast. 2006;23:937. doi: 10.1002/yea.1411. Medline. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meister P, et al. Nuclear factories for signalling and repairing DNA double strand breaks in living fission yeast. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:5064. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg719. Medline. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Takeda J, et al. Radiation induction of delayed recombination in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. DNA Repair (Amst.) 2008;7:1250. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2008.04.006. Medline. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.St. Charles J, Hamilton ML, Petes TD. Meiotic chromosome segregation in triploid strains of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 2010;186:537. doi: 10.1534/genetics.110.121533. Medline. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Natarajan AT. In: DNA Repair and Human Disease. Balajee AS, editor. New York: Landes Bioscience and Springer Science+Business Media; 2006. pp. 61–66. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Duesberg P, Rausch C, Rasnick D, Hehlmann R. Genetic instability of cancer cells is proportional to their degree of aneuploidy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1998;95:13692. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.23.13692. Medline. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thompson SL, Compton DA. Proliferation of aneuploid human cells is limited by a p53-dependent mechanism. J. Cell Biol. 2010;188:369. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200905057. Medline. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lengauer C, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. Genetic instabilities in human cancers. Nature. 1998;396:643. doi: 10.1038/25292. Medline. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sniegowski PD, Gerrish PJ, Lenski RE. Evolution of high mutation rates in experimental populations of E. coli. Nature. 1997;387:703. doi: 10.1038/42701. Medline. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shaver AC, et al. Fitness evolution and the rise of mutator alleles in experimental Escherichia coli populations. Genetics. 2002;162:557. doi: 10.1093/genetics/162.2.557. Medline. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Williams BR, et al. Aneuploidy affects proliferation and spontaneous immortalization in mammalian cells. Science. 2008;322:703. doi: 10.1126/science.1160058. Medline. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.