Abstract

Objectives

To examine methamphetamine use and its association with sexual behavior among young men who have sex with men.

Design

Cross-sectional observational analysis.

Setting

Eight US cities.

Participants

As part of the Adolescent Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions, adolescent boys and young men who have sex with men, aged 12 to 24 years, were recruited from social venues (eg, clubs, parks, and street corners) between January 3, 2005, and August 21, 2006, to complete a study survey.

Main Outcome Measures

Reported methamphetamine use in the past 90 days and reported sexual risk behavior compared with individuals reporting no hard drug use and individuals reporting hard drug use in the past 90 days.

Results

Among 595 adolescent boys and young men, 64 reported recent methamphetamine use, and 444 reported no recent hard drug use (87 reported use of hard drugs other than methamphetamine). Recent methamphetamine use was associated with a history of sexually transmitted diseases (51.6%), 2 or more sex partners in the past 90 days (85.7%), sex with an injection drug user (51.6%), and sex with someone who has human immunodeficiency virus (32.8%) compared with individuals reporting no recent hard drug use (21.1%, 63.1%, 10.7%, and 11.1%, respectively; P<.05 for all [n=441]). Recent users of methamphetamine were more likely to have a history of homelessness (71.9%) and were less likely to be currently attending school (35.9%) compared with individuals reporting no recent hard drug use (28.4% and 60.4%, respectively; P<.001 for both).

Conclusions

Adolescent boys and young men who have sex with men and use methamphetamine seem to be at high risk for human immunodeficiency virus. Prevention programs among this age group should address issues like housing, polydrug use, and educational needs.

THE PREVALENCE OF meth-amphetamine use has been estimated at 43% among men 18 years and older who have sex with men (MSM), and the association between methamphetamine use and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) risk and infection is well documented in this population.1-6 Results from studies3,4 suggest that MSM who use methamphetamine are more likely than those who do not to report the following characteristics: increased number of sex partners, greater likelihood of sex with an HIV-infected partner, and unprotected anal intercourse during their most recent anal sex encounter (66% vs 51%, respectively). Research focuses on older MSM, and little is known about methamphetamine use and sexual behavior among younger MSM (YMSM). Existing data that pertain to YMSM were collected more than 15 years ago, before recent increases in the incidence of HIV.7,8 Behavior, mortality, and treatment have changed dramatically in 15 years.7,8 A 2007 study9 focusing on YMSM (aged 16-24 years) in Chicago, Illinois, confirmed associations found among older MSM. Although these data are informative, more geographically diverse data about methamphetamine use and HIV risk among YMSM are necessary to inform HIV prevention policies focused on this population. The present study addresses this need by examining methamphetamine use and its association with high-risk sexual behavior of adolescent boys and YMSM (aged 12-24 years) recruited through venue-based sampling in 8 US cities.

METHODS

STUDY DESIGN

Connect to Protect is the primary community-based prevention infrastructure of the Adolescent Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions (ATN), a multicenter National Institutes of Health-funded collaborative research ini-tiative of 14 sites in the United States and 1 site in Puerto Rico thatconductsinvestigationsrelatedtoadolescentsandyoungadults aged 12 to 24 years who are living with HIV or who are at risk for HIV.10 Connect to Protect uses community mobilization and coalition-buildingstrategiestobringaboutchangesthataffectstructural features of the environment that exist outside of an individual’s control and may contribute to risk for HIV. At the start of Connect to Protect, ATN sites were asked to focus on 1 sub-population of youth, choosing YMSM, young minority women, or injection drug users (IDUs); 8 sites focused on YMSM and are discussed herein.11,12 These 8 sites included San Francisco, California; Los Angeles, California; San Diego, California; Chicago, Illinois; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Washington, DC; Baltimore, Maryland; and New York, New York.

Data for this study were collected as part of a baseline survey conducted at high-risk venues within the ATN cities. To identify venues for recruitment, 10 to 20 YMSM with HIV were interviewed at various care settings and were asked to identify places (eg, clubs, parks, and street corners) where YMSM congregate.11,13 After identifying an initial list, staff at each site conducted a brief interview at 3 to 5 venues per city to assess whether there were sufficient numbers of eligible participants that could be recruited for a study survey. At the venues, staff approached adolescent boys and young men who seemed to be between 12 and 24 years and asked them about their sex, age, race/ethnicity, and willingness to complete a 1-hour survey. Based on this brief interview, the list of potential recruitment venues was narrowed to 2 to 3 venues per city where 20 to 30 participants per venue could be recruited to complete the study survey. The final set of recruitment venues included public places, such as bars, clubs, parks, street corners, and community-based organizations.13

Each site had 3 months to conduct the study surveys, with the first site beginning interviews on January 3, 2005, and the last site completing interviews on August 21, 2006. Staff used a convenience sampling approach within high-traffic areas of each selected venue to recruit participants who seemed to be within the desired age range. Depending on the venue, the participant was taken to another location on-site or nearby (ie, private room or mobile unit) for the actual study survey to maintain anonymity and to guard the safety of the participants. At each venue, staff recruited 20 to 30 English- or Spanish-speaking YMSM, for a total of 40 to 90 per ATN site. The YMSM were eligible if they reported their birth sex as male, were between the age of 12 and 24 years, and had engaged in voluntary anal or oral sex with a male partner within the past 12 months. Staff obtained verbal informed consent from all participants before conducting the survey. The surveys were administered using an anonymous audio computer-assisted self-administered interview. All participating institutions’ institutional review boards approved the protocol. Incentives for participation included gift certificates, music CDs, or other similar goods, commensurate with local standards.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Participants were divided into the following 3 categories depending on their history of drug use: (1) those who reported methamphetamine use in the past 90 days; (2) those who reported no hard drug use in the past 90 days, including those with no history of drug use and those who may have used hard drugs but not in the past 90 days; and (3) those who reported the use of other hard drugs (excluding methamphetamine) in the past 90 days. Hard drug use was defined as the use of at least 1 of the following drugs in the past 90 days: cocaine, crack, hallucinogens, injection drugs, flunitrazepam (Rohypnol; Hoffman-La Roche, Basel, Switzerland), γ-hydroxybutyric acid, 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (ecstasy), or other drugs (excluding marijuana).

To assess the association of methamphetamine use with HIV sexual risk behavior, regression models were fit to the data using generalized estimating equations to control for possible correlation in the data among participants enrolled at the same venues. In addition, the models controlled for possible confounding by age and race/ethnicity. P<.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

DERIVATION OF DRUG USE COMPARISON GROUPS

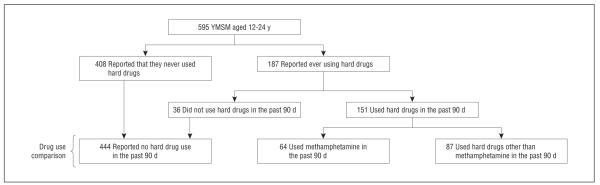

Among 595 YMSM, 408 (68.6%) reported no hard drug use, and 187 (31.4%) reported ever using hard drugs (Figure). Of 187 participants who reported ever using hard drugs, 151 (80.7%) reported using hard drugs within the past 90 days, and 36 (19.3%) did not report using hard drugs in the past 90 days. In preliminary analyses, 408 participants who reported no hard drugs were compared with 36 participants who reported using hard drugs but not in the past 90 days. Because no differences were noted in HIV sexual risk behavior (P>.05), the 2 groups were combined for the analyses that focused on recent drug use in the past 90 days. Sixty-four of 187 participants (34.2%) who ever used hard drugs reported using methamphetamine in the past 90 days (Table 1). Ten of 64 methamphetamine users (15.6%) reported no other type of drug use in the past 90 days; 18 (28.1%) reported a history of injecting nonprescription drugs, with 14 of them reporting injecting drugs 1 or more times in the past 90 days (data not shown).

Figure.

Derivation of drug use comparison groups. YMSM indicates young men who have sex with men

Table 1.

Prevalence of Individual Drug Use in the Past 90 Days Among 187 Young Men Who Have Sex With Men and Who Report Ever Using Hard Drugsa

| No. (%) |

No. Missing |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Drug Used in the Past 90 d | Yes | No | |

| Cocaine (n=181) | 88 (48.6) | 93 (51.4) | 6 |

| Methamphetamine (n=181) | 64 (35.4) | 117 (64.4) | 6 |

| Crack (n=181) | 41 (22.7) | 140 (77.3) | 6 |

| Ecstasy (n=180)b | 69 (38.3) | 111 (61.7) | 7 |

| Rohypnol (n=181)c | 9 (5.0) | 172 (95.0) | 6 |

| GHB (n=181)a | 16 (8.8) | 165 (91.2) | 6 |

| Hallucinogens (n= 181) | 24 (13.3) | 157 (86.7) | 6 |

| Other (n=180) | 53 (29.4) | 127 (70.6) | 7 |

The 408 participants who reported that they never used hard drugs were not asked these questions.

3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine.

Flunitrazepam. d-y-Hydroxybutyric acid

DEMOGRAPHIC CHARACTERISTICS

The YMSM who used methamphetamine in the past 90 days were older than participants who used no hard drugs (P=.03) (Table 2). Among the methamphetamine users, all were older than 18 years except 1. Among participants who used methamphetamine, a smaller proportion was attending school (35.9%) and larger proportions had ever been homeless (71.9%) and had a history of an STD (51.6%) compared with participants who used no hard drugs (60.4%, 28.4%, and 21.1%, respectively; P<.001 for all [n=441). In addition, a sig-nificant difference was noted in the type of venue where YMSM who used methamphetamine were recruited compared with participants who used no hard drugs; the most notable difference was that more methamphetamine users were recruited from community-based organizations (34.4% vs 18.7%, P=.02). Furthermore, participants who used hard drugs other than methamphetamine were more likely than participants who used no hard drugs to be homeless (51.7% vs 28.4%, P<.001) and have HIV (15.2% vs 7.3%, P=.002).

Table 2.

Characteristics of Participants Overall and According to Drug Use Category

| In the Past 90 d, No. (%) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic or Baseline Characteristic | Overall (N=595) |

I Methamphetamine Use (n=64) |

II No Hard Drug Usea (n=444) |

P Value for I vs IIb |

III Hard Drug Use Other Than Methamphetamine (n=87) |

P Value for II vs IIIb |

| Current age, y | .03 | .02 | ||||

| <18 | 79 (13.3) | 1 (1.6) | 71 (16.0) | 7 (8.0) | ||

| ≥18 | 516 (86.7) | 63 (98.4) | 373 (84.0) | 80 (92.0) | ||

| Race/ethnicity | .20 | .93 | ||||

| White | 59 (9.9) | 22 (34.4) | 27 (6.1) | 10 (11.5) | ||

| Black or African American | 234 (39.3) | 8 (12.5) | 195 (43.9) | 31 (35.6) | ||

| Hispanic | 222 (37.3) | 25 (39.1) | 162 (36.5) | 35 (40.2) | ||

| Other or mixed | 80 (13.4) | 9 (14.1) | 60 (13.5) | 11 (12.6) | ||

| Currently attending school | <.001 | .27 | ||||

| Yes | 333 (56.0) | 23 (35.9) | 268 (60.4) | 42 (48.3) | ||

| No | 262 (44.0) | 41 (64.1) | 176 (39.6) | 45 (51.7) | ||

| Highest grade completed | .23 | .74 | ||||

| <High school | 156 (26.2) | 12 (18.8) | 119 (26.8) | 25 (28.7) | ||

| High school or GED | 262 (44.0) | 27 (42.2) | 201 (45.3) | 34 (39.1) | ||

| Some college or technical education | 132 (22.2) | 18 (28.1) | 95 (21.4) | 19 (21.8) | ||

| ≥College graduate | 45 (7.6) | 7 (10.9) | 29 (6.5) | 9 (10.3) | ||

| Ever been homeless | <.001 | <.001 | ||||

| Yes | 217 (36.5) | 46 (71.9) | 126 (28.4) | 45 (51.7) | ||

| No | 378 (63.5) | 18 (28.1) | 318 (71.6) | 42 (48.3) | ||

| Ever had a sexually transmitted disease | <.001 | .05 | ||||

| Yes | 151 (25.5) | 33 (51.6) | 93 (21.1) | 25 (28.7) | ||

| No | 441 (74.5) | 31 (48.4) | 348 (78.9) | 62 (71.3) | ||

| Type of venue where recruited | .02 | .58 | ||||

| Bar or club | 309 (51.9) | 27 (42.2) | 234 (52.7) | 48 (55.2) | ||

| Community-based organization | 117 (19.7) | 22 (34.4) | 83 (18.7) | 12 (13.8) | ||

| Street corner, park, bus, or train station | 169 (28.4) | 15 (23.4) | 127 (28.6) | 27 (31.0) | ||

| HIV infection status | (n = 459) | (n = 50) | (n = 343) | .25 | (n = 66) | .002 |

| Infected | 40 (8.7) | 5 (10.0) | 25 (7.3) | 10 (15.2) | ||

| Uninfected | 419 (91.3) | 45 (90.0) | 318 (92.7) | 56 (84.8) | ||

| Missingc | 136 | 14 | 101 | 21 | ||

Abbreviations: GED, general equivalency diploma; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus.

Includes 408 participants who reported that they never used hard drugs and 36 participants who reported using hard drugs but not in the past 90 days.

P values for type of venue where recruited were derived using Fisher exact test; all others were derived by logistic regression modeling using SAS Proc GENMOD (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina), which is capable of addressing possible correlations among participants interviewed at the same venue. Models were adjusted for age and race/ethnicity except where age was correlated with the characteristic (currently attending school and highest grade completed).

Includes missing responses, participants who were tested but did not go back for results, and those who were tested but did not know their test result; it was impossible to adjust for race/ethnicity when examining the association between HIV infection status and the comparison between groups II and III.

DRUG USE AND HIV SEXUAL RISK BEHAVIOR

More participants who used methamphetamine had 2 or more sex partners in the past 90 days compared with participants who used no hard drugs (85.7% vs 63.1%, P<.001) (Table 3). Significantly fewer participants who used methamphetamine reported that they used a condom every time they had sex with their partners compared with participants who used no hard drugs (33.3% vs 54.3%, P < .001). Similarly, fewer participants who used hard drugs other than methamphetamine always used condoms compared with participants who used no hard drugs (41.9% vs 54.3%, P = .004). Significant differences were also observed between participants who used methamphetamine and those who used no hard drugs in the characteristics of ever having sex with someone with HIV (32.8% vs 11.1%, P=.002) and ever having sex with an IDU (51.6% vs 10.7%, P<.001). Similarly, participants who used no hard drugs were less likely than those who used hard drugs other than methamphetamine to have sex with someone with HIV (11.1% vs 23.8%, P=.003) or have sex with an IDU (10.7% vs 20.0%, P=.047).

Table 3.

Association of Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) Sexual Risk Behavior With Methamphetamine Use in the Past 90 Days Among Young Men Who Have Sex With Men

| In the Past 90 d, No. (%) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIV Sexual Risk Behavior | Overall (N=595) |

I Methamphetamine Use (n=64) |

II No Hard Drug Usea (n=444) |

P Value for I vs IIb |

III Hard Drug Use Other Than Methamphetamine (n=87) |

P Value for II vs IIIb |

| Sex partners in the past 90 d | (n = 592) | (n = 63) | (n=442) | <.001 | (n = 87) | .14 |

| ≥2 | 395 (66.7) | 54 (85.7) | 279 (63.1) | 62 (71.3) | ||

| ≤1 | 197 (33.3) | 9 (14.3) | 163 (36.9) | 25 (28.7) | ||

| Ever had sex with an intravenous drug user | (n = 590) | (n = 64) | (n=441) | <.001 | (n = 85) | .047 |

| Yes | 97 (16.4) | 33 (51.6) | 47 (10.7) | 17 (20.0) | ||

| No | 493 (83.6) | 31 (48.4) | 394 (89.3) | 68 (80.0) | ||

| Ever had sex with someone who has HIV | (n = 577) | (n = 61) | (n=432) | .002 | (n = 84) | .003 |

| Yes | 88 (15.3) | 20 (32.8) | 48 (11.1) | 20 (23.8) | ||

| No | 489 (84.7) | 41 (67.2) | 384 (88.9) | 64 (76.2) | ||

| How often did you use a condomc | (n = 531) | (n = 51) | (n=387) | <.001 | (n = 93) | .004 |

| Not every time | 265 (49.9) | 34 (66.7) | 177 (45.7) | 54 (58.1) | ||

| Every time | 266 (50.1) | 17 (33.3) | 210 (54.3) | 39 (41.9) | ||

Includes 408 participants who reported that they never used hard drugs and 36 participants who reported using hard drugs but not in the past 90 days.

Derived from logistic regression modeling using SAS Proc GENMOD (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina), which is capable of addressing possible correlations among participants interviewed at the same venue and behaviors engaged in with multiple sex partners. Models were adjusted for age and race/ethnicity.

Multiple sex partners were possible.

COMMENT

The reported prevalence of sexual risk behavior in this study among YMSM is consistent with the current body of research. Methamphetamine users were more likely to report lower rates of condom use and higher rates of sexually transmitted diseases, sex with IDUs, use of other hard drugs, and multiple sex partners in the past 90 days. As seen among YMSM in Chicago,9 these data demonstrate that YMSM at sites in diverse geographic locations who use methamphetamine are at increased risk for HIV. The reported high rates of sex with IDUs in this sample of YMSM suggest that more research is needed to distinguish the extent of risk associated with sexual behavior vs risk that may be a result of sharing injection drug paraphernalia.

This study has several limitations that are in line with most other studies of MSM and drug use. First, the sample is not representative of all YMSM in the United States. We focused on YMSM venues that may have been representative of higher-risk men, and our study population was limited to venues in the 8 ATN cities. Second, participants who may not have chosen to disclose sexual behavior were not represented in this study. Third, methamphetamine use was classified on the basis of self-report and may have been underreported, creating a classification bias. Fourth, we only included YMSM who had engaged in anal or oral sex in the past year.

Nevertheless, the findings of our study suggest that there is a need to develop substance abuse prevention and treatment programs as part of HIV prevention for YMSM. Prevention programs need to consider the unique stages of YMSM who are developing their sexual, racial/ethnic, and adult identities. To be most effective among YMSM who use methamphetamine, prevention programs should ad-dress issues, such as housing, polydrug use, and educational needs. Although we cannot conclude from this study that YMSM who use methamphetamine are more likely to disengage from educational programs than to complete their programs successfully, our preliminary analyses indicate a need to further investigate the correlation between methamphetamine use and diminishing school enrollment in this population. Prevention efforts targeting YMSM who use methamphetamine should also ensure that partner selection is addressed, as they showed higher rates of having sex with IDUs and individuals with HIV.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: This study was supported by grants 5 U01 HD04053 and 5 U01 HD40474 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, with supplemental funding from the National Institute on Drug Abuse and the National Institute of Mental Health.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: Study concept and design: Freeman, Walker, Garofalo, Willard, and Ellen. Analysis and inter-pretation of data: Harris and Ellen. Drafting of the manuscript: Freeman, Walker, Harris, Willard, and Ellen. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Walker, Harris, Garofalo, Willard, and Ellen. Statistical analysis: Harris. Obtained funding: Ellen. Administrative, technical, and material support: Willard and Ellen. Study supervision: Garofalo, Willard, and Ellen.

Group Information: The Adolescent Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions 016b Team members include Larry Muenz, PhD, William Barnes, PhD, Gary Harper, PhD, and Dina Monte, RN, BSN. The following sites and personnel participated in this study: University of Maryland, College Park: Ligia Peralta, MD, Bethany Griffin Deeds, PhD, and Kalima Young. Montefiore Medical Center, Bronx, New York: Donna Futterman, MD, and Sharon S. Kim, MPH. Children’s Hospital of Los Angeles, Los Angeles, California: Marvin Belzer, MD, Miguel Martinez, MSW/MPH, and Veronica Montenegro. The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Bret J. Rudy, MD, Antonio Cardoso, and Marne Castillo. Children’s National Medical Center, Washington, DC: Larry D’Angelo, MD, and Bendu C. Walker, MPH. Children’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts: Cathryn Samples, MD, and Judith Palmer-Castor, PhD. Stroger Hospital of Cook County, Chicago, Illinois: Jaime Martinez and Lisa Henry-Reed. Children’s Diagnostic and Treatment Center, Fort Lauderdale, Florida: Ana Puga, MD, Jessica Roy, MSW, and Dianne Batchelder, RN. University of Miami, Miami, Florida: Lawrence Friedman, MD, Kenia Sanchez, MSW, and Ben Quiles. University of South Florida, Tampa: Patricia Emmanuel, MD, Diane Straub, MD, MPH, GeorgetteKing,MPA,andChodasessieMorgan.TulaneUniversity, New Orleans, Louisiana: Sue Ellen Abdalian, MD, and Sybil Schroeder, PhD. Mount Sinai Adolescent Health Center, New York, New York: Linda Levin, MD, Christopher Moore, MPH,and Kelly Sykes, PhD.UniversityofPuerto Rico, Mayagüez: Irma Febo, MD, Ileana Blasini, MD, MPH, Ibrahim Ramos-Pomales, MPHE, and Carmen Rivera-Torres, RN, MPH. University of California, San Diego: Stephen A. Spector, MD, and Stephanie Lehman, PhD. University of California, San Francisco: Anna Barbara Moscicki, MD, Colette Auerswald, MD, and Kevin Sniecinski, MPN.

Financial Disclosure: None reported.

Additional Contributions: Contributing to the study were Craig Wilson, MD, Cindy Partlow, MEd, Jim Korelitz, PhD, Barbara Driver, MS; Lori Perez, PhD; Rick Mitchell, MS; and Stephanie Sierkierka, BS. We acknowledge the contributions of the youth who participate in our national and local youth community advisory boards for their thoughtful contributions to the work of Connect to Protect and the staff at the local public health departments, police departments, state agencies, and other sources who provided the data used in this project.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ostrow DG, Plankey MW, Cox C, et al. Specific sex-drug combinations contribute to the majority of recent HIV seroconversions among MSM in the MACS. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;51(3):349–355. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181a24b20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Menza TW, Hughes JP, Celum CL, Golden MR. Prediction of HIV acquisition among men who have sex with men. Sex Transm Dis. 2009;36(9):547–555. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181a9cc41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Forrest DW, Metsch LR, LaLota M, Cardenas G, Beck DW, Jeanty Y. Crystal methamphetamine use and sexual risk behaviors among HIV-positive and HIV-negative men who have sex with men in South Florida. J Urban Health. 2010;87(3):480–485. doi: 10.1007/s11524-009-9422-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carey JW, Mejia R, Bingham T, et al. Drug use, high-risk sex behaviors, and increased risk for recent HIV infection among men who have sex with men in Chicago and Los Angeles. AIDS Behav. 2009;13(6):1084–1096. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9403-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schwarcz S, Scheer S, McFarland W, et al. Prevalence of HIV infection and predictors of high-transmission sexual risk behaviors among men who have sex with men. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(6):1067–1075. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.072249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grov C, Kelly BC, Parsons JT. Polydrug use among club-going young adults recruited through time-space sampling. Subst Use Misuse. 2009;44(6):848–864. doi: 10.1080/10826080802484702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McNall M, Remafedi G. Relationship of amphetamine and other substance use to unprotected intercourse among young men who have sex with men. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153(11):1130–1135. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.153.11.1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Waldo CR, McFarland W, Katz MH, MacKellar D, Valleroy LA. Very young gay and bisexual men are at risk for HIV infection: the San Francisco Bay Area Young Men’s Survey II. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2000;24(2):168–174. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200006010-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garofalo R, Mustanski BS, McKirnan DJ, Herrick A, Donenberg GR. Methamphetamine and young men who have sex with men: understanding patterns and correlates of use and the association with HIV-related sexual risk. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007;161(6):591–596. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.161.6.591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ziff MA, Harper GW, Chutuape KS, et al. Adolescent Medicine Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Intervention. Laying the foundation for Connect to Protect: a multi-site community mobilization intervention to reduce HIV/AIDS incidence and prevalence among urban youth. J Urban Health. 2006;83(3):506–522. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9036-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barnes W, D’Angelo L, Yamazaki M, et al. Adolescent Trials Network for HIV/ AIDS Interventions. Identification of HIV-infected 12- to 24-year-old men and women in 15 US cities through venue-based testing. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010;164(3):273–276. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Geanuracos CG, Cunningham SD, Weiss G, Forte D, Reid LM, Ellen JM. Use of geographic information systems for planning HIV prevention interventions for high-risk youths. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(11):1974–1981. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.076851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chutuape KS, Ziff M, Auerswald C, Castillo M, McFadden A, Ellen J. Adolescent Medicine Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Intervention. Examining differences in types and location of recruitment venues for young males and females from urban neighborhoods: findings from a multi-site HIV prevention study. J Urban Health. 2009;86(1):31–42. doi: 10.1007/s11524-008-9329-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]