Abstract

Approximately 94% of patients with spinal muscular atrophy lack both copies of SMN1 exon 7, and most carriers have only one copy of SMN1 exon 7. We described previously the effect of SMN1/SMN2 heteroduplex formation on SMN gene dosage analysis, which is a multiplex quantitative PCR assay to determine the copy numbers of SMN1 and SMN2 using DraI digestion to differentiate SMN2 from SMN1. We describe herein the quantification of PCR bias between SMN1 exon 7 and SMN2 exon 7, which differ by only one nucleotide that is not present in either primer binding site. Using samples from 272 individuals with various SMN genotypes, we found that the amplification efficiency of SMN2 was consistent only approximately 80% that of SMN1. Thus, even a single nucleotide polymorphism, not in primer binding sites, can cause reproducible PCR bias. The precision and accuracy of our SMN gene dosage analysis are high because our assay design and controls take advantage of the consistency of the PCR bias. As additional clinically significant single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) are discovered, assessment of PCR bias, and judicious selection of standards and controls, will be increasingly important for quantitative PCR assays.

Spinal muscular atrophy (SMA: type I, MIM no. 253300; type II, MIM no. 253550; type III, MIM no. 253400) is an autosomal recessive disorder associated with loss of motor neurons in the anterior horn of the spinal cord and caused by mutations in the Survival Motor Neuron 1 gene (SMN1; MIM no. 600354) on 5q13. 1 Coding regions of SMN1 and its centromeric homologue, SMN2 (MIM no. 601627), differ in only one base. 2 This C-to-T substitution in SMN2 exon 7 affects the activity of an exonic splice enhancer and alters the splicing pattern of SMN2 mRNA, 3 resulting in a lower level of full-length SMN transcript from SMN2 than from SMN1. 4 , 5 , 6 SMN2 was shown to be unique to Homo sapiens. 7

Approximately 94% of clinically typical SMA patients lack both copies of SMN1 exon 7. 8 SMN gene dosage analysis, a method to determine the copy number of SMN1, can be used to identify SMA carriers. Exon 7 of SMN1 and SMN2 are co-amplified with genomic and internal standards. The PCR products are then digested with DraI, which cuts only SMN2 exon 7 PCR products, followed by quantification of the PCR products. 9 , 10 , 11 Other methods for SMN gene dosage analysis have been described. 12 , 13 , 14 A single copy of SMN1 by gene dosage analysis confirms carrier status; this analysis is therefore of clinical importance. A single-copy result also supports the diagnosis of SMN1-related SMA in an affected individual, who may have one deleted allele and one allele with a small intragenic mutation. However, the final diagnosis depends largely on the index of clinical suspicion. 15 This is because the frequency of single-copy carriers in the general population (∼2%) approaches the frequency of individuals affected with SMN1-related SMA who have a single-copy test result (∼3.6% 12 ). 16

The copy number of SMN2 correlates inversely with disease severity. 9 , 10 , 12 , 13 , 14 Feldkötter et al 14 found that SMN2 copy number also correlates directly with length of survival. Potential therapies for SMA include approaches to increase the expression of full-length transcripts from SMN2. Full-length SMN2 transcripts are increased in vitro and in vivo by sodium butyrate, 17 and in vitro by aclarubicin. 18 Hence, in the future, accurate determination of SMN2 copy number may have both prognostic and therapeutic significance.

We described previously the effect of SMN1/SMN2 heteroduplex formation on SMN gene dosage analysis. 11 We calculated that unless SMN2 is absent, apparent SMN1 peaks contain between approximately 2.9% and approximately 14% SMN2 PCR products (depending on the genotype) due to DraI-undigestable SMN1/SMN2 heteroduplexes. 11 However, in our experience, there seemed to be less SMN2 PCR product than SMN1 PCR product in almost all samples, even after correcting for heteroduplex formation. The hypothesis that incomplete DraI digestion falsely increased the SMN1 signal and decreased the SMN2 signal seemed unlikely because of assay controls lacking SMN1, in which undigested SMN2 signal has never been detected. 11 We hypothesized that there might be a considerable difference in PCR efficiency (PCR bias) between SMN1 and SMN2. Using a large number of samples in our SMN gene dosage analysis, a robust quantitative PCR assay, we quantify herein consistent PCR bias caused by the single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) between SMN1 exon 7 and SMN2 exon 7. We also validate methods to determine SMN2 copy number. The precision and accuracy of our SMN gene dosage analysis are high because our assay design and controls take advantage of the consistency of the PCR bias.

PCR bias caused by an SNP, not in primer binding sites, can significantly affect the accuracy and precision of quantitative PCR assays. To assure high precision and accuracy of quantitative PCR assays, standards and controls must be chosen judiciously, and the signal intensities of the PCR products must be calculated and normalized appropriately. In addition, close monitoring of results on clinical samples and controls/standards is essential for quality assurance in any clinical molecular diagnostic laboratory that performs quantitative PCR. As additional clinically significant SNPs are discovered, assessment of PCR bias will be increasingly important.

Materials and Methods

Sample Collection and DNA Extraction

Using Puregene reagents (Gentra Systems, Minneapolis, MN), genomic DNA was extracted from peripheral blood specimens that were received with informed consent by the Molecular Pathology Laboratory of the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania for SMN1 copy number determination on a clinical basis. Results from a sequential series of 272 samples were selected retrospectively and anonymized for this study. 11

SMN1 and SMN2 Copy Number Assay (SMN Gene Dosage Analysis)

SMN1 gene dosage analysis was originally developed by McAndrew et al 9 and modified as a non-radioisotopic assay as described previously. 10 The assay has since been modified further, using 23 cycles of PCR and the ABI Prism 310 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). 11 All test samples were analyzed in duplicate using the same PCR master mix. The assay takes advantage of the SNP in exon 7 to distinguish SMN1 from SMN2 after DraI digestion. The copy number of SMN1 per cell (or, more precisely, per diploid genome) was determined as described previously. 11 Briefly, we first normalize the SMN1 signal of each sample, using both a genomic standard (CFTR exon 4), as well as internal standards for SMN1 and CFTR that are added to the PCR reaction. We then normalize the result to the mean of five control samples, each with two copies of SMN1, to obtain the SMN1 value designated as “C(SMN1),” (Table 1) which stands for “calculated SMN1,” 11 as described in the Appendix. Theoretically, C(SMN1) should be close to an integer number, and should indicate the copy number of SMN1. The use of control samples with two copies of SMN1 were validated as described. 10 , 11

Table 1.

Definitions of Abbreviations

| Abbreviation | Definition |

|---|---|

| X:Y | (SMN1 copy number):(SMN2 copy number) |

| C(SMN1) | Calculated SMN1 signal |

| N(SMN2) | Normalized SMN2 signal |

| C(SMN2) | Calculated SMN2 signal relative to SMN1 |

| MC(SMN1)X:Y | Mean of C(SMN1) in an X:Y genotype |

| MN(SMN2)X:Y | Mean of N(SMN2) in an X:Y genotype |

| MC(SMN2)X:Y | Mean of C(SMN2) in an X:Y genotype |

| %SMN2X:Y | Average fractional contribution of SMN2 to total MC(SMN1)X:Y |

| PBX:Y | (SMN2 PCR efficiency)/(SMN1 PCR efficiency) in an X:Y genotype in average |

We determined SMN2 copy number by comparing the SMN2 signal to the SMN1 signal, assuming that the SMN2 signal is approximately 70% of the SMN1 signal for equivalent copy numbers, as described previously. 11 As described in Results, we verified SMN2 copy number determination by calculating a normalized SMN2 signal, which we refer to as “N(SMN2)” (see Appendix). N(SMN2) for each sample should be close to an integer number, and should indicate the copy number of SMN2. We refer to a genotype of SMN1 and SMN2 by indicating the SMN1 copy number and the SMN2 copy number separated by a colon. For example, “2:1” stands for a genotype with two copies of SMN1 and one copy of SMN2.

The coefficient of variation (CV) between the two C(SMN1) values for each sample in the duplicate testing of our 272 samples ranged from 0% to 12%, with a mean of 2.5% and a median of 1.9%. 11 The CV between the two N(SMN2) values for each sample in the duplicate testing of our 259 samples (excluding the 2:0 genotype) ranged from 0% to 20%, with a mean of 3.4% and a median of 2.6%. The average values of C(SMN1), C(SMN2) (see below) and N(SMN2) from the two runs for each sample were used for further analyses.

Quantification of PCR Bias between SMN1 and SMN2

To quantify PCR bias between SMN1 and SMN2, we calculated the SMN2 signal relative to that of SMN1 [“C(SMN2)”], using the same set of external quantification standards as C(SMN1) (see Appendix for details). To calculate PCR bias between SMN1 and SMN2 accurately, we normalized the SMN1 and SMN2 signals to the same standards. We refer to the means of C(SMN1), C(SMN2), and N(SMN2) for a given SMN1:SMN2 genotype X:Y as MC(SMN1)X:Y, MC(SMN2)X:Y, and MN(SMN2)X:Y, respectively. Because SMN1/SMN2 heteroduplexes cannot be digested by DraI, they falsely increase the SMN1 signal and falsely decrease the SMN2 signal. 11 Thus, we first needed to correct our values of MC(SMN1)X:Y and MC(SMN2)X:Y for the false increase of the SMN1 signal, and the false decrease of the SMN2 signal, caused by SMN1/SMN2 heteroduplex formation. Because SMN1/SMN2 heteroduplexes cannot form in samples of the 2:0 genotype, we quantified SMN1/SMN2 heteroduplex formation by comparing the MC(SMN1)X:Y to the MC(SMN1)2:0. 11 The amount of SMN1/SMN2 heteroduplexes is expressed as the percentage of the SMN1 signal MC(SMN1)X:Y that is contributed by SMN2 (which we refer to as “%SMN2X:Y ” for a genotype X:Y). The extent of heteroduplex formation depends on the ratio of SMN1 copies to SMN2 copies, and therefore must be quantified separately for each genotype. 11 We re-analyzed the data of Ogino et al 11 after changing the genotype assignments from 1:3 to 1:4 for two samples (see below), resulting in minor changes in the values for %SMN2 X:Y in these genotypes (Table 2) . After taking into account heteroduplex formation, we quantified PCR bias between SMN1 and SMN2 (referred to as “PBX:Y ” for a given genotype X:Y) for each genotype, by dividing the corrected value for SMN2 per SMN2 copy by the corrected value for SMN1 per SMN1 copy. Our methods for calculating the PCR bias (PBX:Y) are described in detail in the Appendix.

Table 2.

Measurement of PCR Bias

| Genotype (X:Y) | N* | MC(SMN1)X:Y | MN(SMN2)X:Y | SD† of N(SMN2) | MC(SMN2)X:Y | %SMN2X:Y | PBX:Y |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2:0 | 13 | 1.902 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | N/A‡ |

| 1:1 | 27 | 1.018 | 1.028 | 0.088 | 0.724 | 6.6% | 0.832 |

| 2:1 | 53 | 1.973 | 0.962 | 0.109 | 0.678 | 3.6% | 0.788 |

| 3:1 | 11 | 2.938 | 0.948 | 0.107 | 0.668 | 2.9% | 0.792 |

| 1:2 | 57 | 1.034 | 2.045 | 0.156 | 1.440 | 8.0% | 0.801 |

| 2:2 | 81 | 2.033 | 2.001 | 0.184 | 1.409 | 6.5% | 0.810 |

| 3:2 | 6 | 2.999 | 2.069 | 0.071 | 1.457 | 4.9% | 0.843 |

| 1:3 | 16 | 1.063 | 3.181 | 0.199 | 2.241 | 10.0% | 0.822 |

| 2:3 | 3 | 2.234 | 3.269 | 0.271 | 2.302 | 14.9% | 0.923 |

| 1:4 | 4 | 1.097 | 4.057 | 0.184 | 2.857 | 13.3% | 0.790 |

Each symbol is described in Table 1 . Note that PBX:Y (SMN2 PCR efficiency relative to SMN1 PCR efficiency) is approximately 0.8, regardless of SMN genotype, except for the 2:3 (N = 3).

number of cases;

standard deviation;

not applicable.

Results

Validation of SMN2 Copy Number Determination

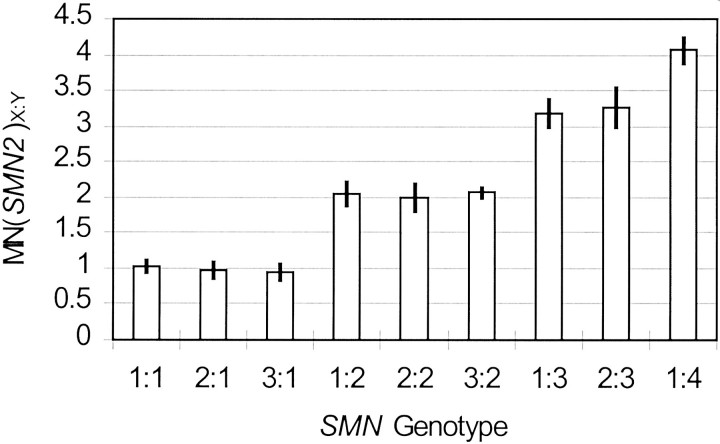

MN(SMN2)X:Y values, which should be close to integer numbers and should indicate SMN2 copy numbers, are shown in Figure 1 and Table 2 . There was no overlap of MN(SMN2)X:Y ± 2 SD between genotypes of one copy (0.734 to 1.21), two copies (1.63 to 2.37) and three copies (2.73 to 3.81) of SMN2. Therefore, assigning the integer number of SMN2 copies was straightforward, though the power to discriminate between three and four copies was somewhat less than between the other pairings. The MN(SMN2)X:Y ± 2 SD of the 1:3 genotype (2.78 to 3.58; N = 16) did not overlap with that of the 1:4 genotype (3.69 to 4.42; N = 4). The MN(SMN2)X:Y ± 2 SD of the 2:3 genotype (N = 3) was 2.73 to 3.81. The upper limit (+2 SD) of 3.81 was high, but we lack samples of the 2:4 genotype (which may not even exist) to compare with. More samples are necessary to validate fully the power of our assay to discriminate between three and four copies of SMN2. One sample with a value of 2.49 for N(SMN2) could not be excluded from the 2:3 genotype or from the 2:2 genotype by the Grubbs-Smirnov test (both P > 0.1). The precise SMN2 copy number of this sample was therefore undetermined. When we included the sample with a value of 2.49 for N(SMN2) in the 2:2 genotype (making N = 82) or in the 2:3 genotype (making N = 4), the MN(SMN2)2:2 was 2.01 with an SD of 0.19, or the MN(SMN2)2:3 was 3.07 with an SD of 0.45. Two other samples with values of 3.98 and 3.93 for N(SMN2) were previously considered to be in the 1:3 genotype 11 but were included in the 1:4 genotype in this study.

Figure 1.

The normalized SMN2 signal, N(SMN2), in various SMN genotypes. The x axis represents SMN genotypes designated as “(SMN1 copy number):(SMN2 copy number)” as in the text. The y axis represents the normalized SMN2 signal, N(SMN2). The mean N(SMN2), MN(SMN2)X:Y, is represented by a column. The vertical line across the top of each column represents ± 1 SD. Note that N(SMN2) values are clustered around integer numbers, which indicate SMN2 copy numbers.

Quantification of PCR Bias between SMN1 and SMN2

To quantify PCR bias between SMN1 and SMN2, we performed SMN gene dosage analysis on samples from 272 individuals. The calculated PCR bias (PBX:Y), ie, the ratio of the corrected values for C(SMN2) per actual copy number of SMN2, to the corrected values for C(SMN1) per actual copy number of SMN1, was consistently less than 1 (Table 2) , indicating a PCR bias in favor of SMN1 amplification. The PBX:Y ranged from 0.788 to 0.843 for all genotypes except for the 2:3 genotype (N = 3) with the PB2:3 value of 0.923 (Table 2) . PCR bias was reproducible between samples and between runs. When we included the one sample with a value of 2.49 for N(SMN2) in the 2:2 genotype or the 2:3 genotype, PB2:2 was 0.813 or PB2:3 was 0.867, respectively.

To determine the consistency of SMN1/SMN2 heteroduplex formation and PCR bias between SMN1 and SMN2, we calculated the uncorrected ratio of C(SMN2)/Y to C(SMN1)/X for each sample in a given genotype X:Y. The mean ratios for each genotype were (mean ± SD): 0.651 ± 0.083 for 2:3, 0.729 ± 0.016 for 3:2, 0.723 ± 0.061 for 1:3, 0.694 ± 0.065 for 2:2, 0.681 ± 0.067 for 3:1, 0.698 ± 0.056 for 1:2, 0.687 ± 0.075 for 2:1, and 0.712 ± 0.050 for 1:1. Thus, heteroduplex formation and PCR bias were reproducible between samples.

Discussion

PCR bias has been described previously. 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 Because all PCR is biased in the sense that specific and non-specific targets can be discriminated, we only consider herein PCR bias in the setting of identical primer binding sites. PCR bias may be caused by differences in template lengths, random variations in template number (especially with very small initial numbers), and random variations in PCR efficiency in each cycle. Liu et al 24 reported PCR inhibition due to a point mutation not in primer binding sites. However, Liu et al 24 analyzed only three samples with the mutation; they did not use competitive, quantitative PCR; and primers that did not show PCR bias annealed at sites distinct from the (overlapping) primers that did, raising the possibility of a primer-site polymorphism. Warnecke et al 21 measured the effects of PCR bias on the quantification of methylation status using bisulphite-treated DNA. They found approximately 30-fold and 20-fold differences in amplification efficiency favoring the unmethylated alleles of the human Rb and p16 genes, respectively. However, the effects of heteroduplex formation were not considered in their restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analyses. 21 Barnard et al 19 found striking differences in the amplification efficiency of wild-type and mutant clones of the p53 and k-ras genes in favor of wild-type sequences, either in a single reaction tube or in different reaction tubes. Although based on a limited number of samples, the data of Bernard et al 19 indicate that a point mutation, not in primer binding sites, can cause PCR bias. In addition, their data suggest that wild-type sequences derived from normal cells in a clinical sample can potentially mask mutant sequences in a PCR-based assay for mutation detection. However, their use of cloned DNA precluded the normalization of template input with a genomic reference sequence for the most accurate quantification of PCR bias. 19

Quantification of PCR bias due to an SNP is complicated by heteroduplex formation between the two sequences, and by the need to quantify nearly identical PCR products independently. We present herein methods to overcome these difficulties. We describe the quantification of PCR bias due to an SNP using a large number of samples in our robust SMN gene dosage analysis. The consistency of our PCR bias measurements between samples and between genotypes reinforces the validity of our results. We used samples with various copy numbers of SMN1 and of SMN2, which were present in precise integer ratios. In addition, the simultaneous amplification of a genomic reference sequence (CFTR exon 4) allowed us to normalize initial template input.

We also evaluated the effect of PCR bias on our SMN gene dosage analysis, 10 , 11 which is based on the method of McAndrew et al 9 A priori, we assumed that the amplification efficiencies for SMN1 and SMN2 would be nearly identical since the single nucleotide difference in the segment amplified is not in the primer binding sites. The data presented herein demonstrate that this assumption was incorrect. The PCR bias between SMN1 and SMN2, and any other PCR bias that may occur between the various genomic and internal-standard sequences in our assay, was consistent between samples and between runs, which allows us to maintain assay precision. Because SMN2 amplifies approximately 20% less efficiently than SMN1 in our assay, we normalize SMN2 signals using SMN2 signals from controls of known SMN2 copy number. For SMN gene dosage analysis, the laboratory should verify that the ratio of apparent SMN2 signal to apparent SMN1 signal is consistent in each SMN genotype. In our assay, this ratio is approximately 70% because both PCR bias and heteroduplex formation cause an apparent increase in the SMN1 signal and an apparent decrease in the SMN2 signal.

The cause of PCR bias due to an SNP or a point mutation not in primer binding sites is poorly understood. Bernard et al 19 hypothesized that the sequence CXGG might cause PCR bias. The segment of SMN1 and SMN2 amplified in our assay contains the sequence ... CAGGGTTT(C or T)A(G to A)ACAA...(where the reverse-primer binding site is italicized, “C or T ” refers to the SMN exon 7 polymorphism, and “G to A ” refers to the nucleotide change generated by primer mismatch to create a DraI site in SMN2 PCR product). The CXGG sequence is present, though not at the site of the polymorphism. One may hypothesize that a difference in the exact locations of SMN1 and SMN2 on 5q13 might cause PCR bias. However, if that were true, converted telomeric SMN2 (or centromeric SMN1, if it exists) would amplify with an efficiency similar to that of native telomeric SMN1 (or centromeric SMN2, respectively). Samples in our study with converted telomeric SMN2 would have had less or no PCR bias, since at least one SMN2 copy would have been amplified with a similar efficiency to that of the native SMN1. The consistency and reproducibility of our PCR bias data do not support this hypothesis. Moreover, it seems unlikely that a particular chromosomal structure would be present in our purified DNA samples. Alternatively, because the polymorphism lies only one nucleotide from the 3′ end of the reverse-primer binding site, it might affect the initial interaction of the DNA polymerase with the template and dNTP. The SNP might also affect initial primer binding.

Heteroduplex formation should diminish as PCR cycle number decreases because it depends on the amount of PCR products formed. 11 In contrast, PCR bias may be present even after the initial cycles of amplification, which could affect quantification in real-time PCR assays. Recently, Feldkötter et al 14 described a real-time PCR assay for the quantification of SMN1 and SMN2 copy numbers. They used allele-specific PCR, with slightly different primer pairs for SMN1 and SMN2. In their assay, SMN2 amplified somewhat better than SMN1. The precision and accuracy of the method of Feldkötter et al 14 are similar to, or slightly lower than, those of our method ( 10 , 11 and data herein), which is a modification of the original method of McAndrew et al 9 All of these methods, 9 , 10 , 11 , 14 in addition to that of Gérard et al, 13 determine SMN1 and SMN2 copy numbers reliably. Gérard et al 13 also demonstrated an efficiency bias in their primer-extension assay, slightly in favor of SMN2, even though they generated larger products from SMN2 (27 bp) than those from SMN1 (23 bp). In contrast, they found less or no PCR bias between the SMN sequence and its 3 bp-smaller SMN internal standard, and between their genomic reference (PBGD) and its 5 bp-larger internal standard. 13 Thus PCR bias appears both primer- and template-specific.

In conclusion, even a single nucleotide difference, not in primer binding sites, can cause reproducible PCR bias. The precision and accuracy of our SMN gene dosage analysis are high because our assay design and controls take advantage of the consistency of the PCR bias. As additional clinically significant SNPs in the human genome are discovered, assessment of PCR bias, and judicious selection of standards and controls, will be increasingly important for quantitative PCR assays.

Acknowledgments

We thank Patricia E. McAndrew and Thomas W. Prior for generously providing the plasmids containing the SMN and CFTR internal standard inserts; Debra G. B. Leonard, Hanna Rennert, Vivianna Van Deerlin, Cynthia Turino, and Treasa Smith for their management or performance of our clinical SMN gene dosage analysis; and George L. Mutter, Charles S. Fuchs, Sizhen Gao, Sabina Signoretti, Massimo Loda, and Edward A. Fox for helpful discussion and suggestions.

APPENDIX

1. Calculation of SMN1 and SMN2 copy number

To quantify SMN1 and SMN2 copy number, we defined signal intensity as the relevant peak area on an ABI Prism 310 electropherogram. The signal intensities of the relevant peaks are designated as follows:

A1, SMN internal standard PCR product;

A2, SMN2 PCR product;

A3, SMN1 PCR product;

A4, CFTR internal standard PCR product;

A5, CFTR PCR product.

As described previously by Ogino et al, 11

|

where k3is constant in a single batch of runs using the same PCR master mix, and,

|

We obtained a mean of k 3, designated as k 3*, from Equation (2) in five control samples with two copies of SMN1, comprising three with the 2:2 genotype and two with the 2:1 genotype.

From Equation (1)

|

Equation (3) is designated herein as the “calculated SMN1 signal” or C(SMN1). Similarly,

|

where k 4 is constant in a single batch of runs. (A2/A1)÷(A5/A4) is normalized as follows:

|

We obtained a weighted average of k 4, designated as k 4*, from Equation 5 in seven control samples comprising three with the 2:2 genotype, two with the 2:1 genotype, one with the 1:2 genotype, and one with the 1:1 genotype: ie, the sum of (A2/A1) ÷ (A5/A4) was divided by 11, the total number of copies of SMN2 in the seven samples.

From Equation 4

|

Equation 6 is designated herein as the “normalized SMN2 signal” or N(SMN2).

2. Measurement of PCR Bias between SMN1 and SMN2 (PBX:Y)

We defined the “calculated SMN2 signal relative to SMN1” or “C(SMN2)” as follows {using k 3*, which is defined above for the calculation of C(SMN1)}:

|

We define the mean C(SMN1) values and the mean C(SMN2) values for each genotype X:Y as MC(SMN1)X:Y and MC(SMN2)X:Y, respectively. We quantified the fraction of SMN2 products derived from SMN1/SMN2 heteroduplexes in an SMN1 signal in the genotype X:Y as described previously, 11 and designate this fraction as %SMN2 X:Y. The corrected (for heteroduplex formation) signal intensity for SMN1, per copy of SMN1, is:

|

Likewise, the corrected (for heteroduplex formation) signal intensity for SMN2, per copy of SMN2, is:

|

Thus, the difference in amplification efficiency (PCR bias) between SMN1 and SMN2 in a genotype X:Y, which we designate as “PBX:Y”, is defined as the corrected (for heteroduplex formation) SMN2 signal intensity per copy of SMN2, divided by the corrected (for heteroduplex formation) SMN1 signal intensity per copy of SMN1, or (from Equations 8 and 9 ):

|

Address reprint requests to Shuji Ogino, M.D., Ph.D., Department of Pathology, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, 75 Francis Street, Amory 3rd Floor, Boston, MA 02115. E-mail: sogino@partners.org.

References

- 1.Lefebvre S, Burglen L, Reboullet S, Clermont O, Burlet P, Viollet L, Benichou B, Cruaud C, Millasseau P, Zeviani M, Le Paslier D, Frezal J, Cohen D, Weissenbach J, Munnich A, Melki J: Identification and characterization of a spinal muscular atrophy-determining gene. Cell 1995, 80:155-165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burglen L, Lefebvre S, Clermont O, Burlet P, Viollet L, Cruaud C, Munnich A, Melki J: Structure and organization of the human survival motor neurone (SMN) gene. Genomics 1996, 32:479-482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pellizzoni L, Kataoka N, Charroux B, Dreyfuss G: A novel function for SMN, the spinal muscular atrophy disease gene product, in pre-mRNA splicing. Cell 1998, 95:615-624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Monani UR, Lorson CL, Parsons DW, Prior TW, Androphy EJ, Burghes AH, McPherson JD: A single nucleotide difference that alters splicing patterns distinguishes the SMA gene SMN1 from the copy gene SMN2. Hum Mol Genet 1999, 8:1177-1183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lorson CL, Hahnen E, Androphy EJ, Wirth B: A single nucleotide in the SMN gene regulates splicing and is responsible for spinal muscular atrophy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1999, 96:6307-6311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jong YJ, Chang JG, Lin SP, Yang TY, Wang JC, Chang CP, Lee CC, Li H, Hsieh-Li HM, Tsai CH: Analysis of the mRNA transcripts of the survival motor neuron (SMN) gene in the tissue of an SMA fetus and the peripheral blood monoclear cells of normals, carriers, and SMA patients. J Neurol Sci 2000, 173:147-153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rochette CF, Gilbert N, Simard LR: SMN gene duplication and the emergence of the SMN2 gene occurred in distinct hominids: SMN2 is unique to Homo sapiens. Hum Genet 2001, 108:255-266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wirth B: An update of the mutation spectrum of the survival motor neuron gene (SMN1) in autosomal recessive spinal muscular atrophy (SMA). Hum Mutat 2000, 15:228-237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McAndrew PE, Parsons DW, Simard LR, Rochette C, Ray PN, Mendell JR, Prior TW, Burghes AH: Identification of proximal spinal muscular atrophy carriers and patients by analysis of SMNT and SMNC gene copy number. Am J Hum Genet 1997, 60:1411-1422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen KL, Wang YL, Rennert H, Joshi I, Mills JK, Leonard DG, Wilson RB: Duplications and de novo deletions of the SMNt gene demonstrated by fluorescence-based carrier testing for spinal muscular atrophy. Am J Med Genet 1999, 85:463-469 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ogino S, Leonard DGB, Rennert H, Gao S, Wilson RB: Heteroduplex formation in SMN gene dosage analysis. J Mol Diagn 2001, 3:150-157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wirth B, Herz M, Wetter A, Moskau S, Hahnen E, Rudnik-Schoeneborn S, Wienker T, Zerres K: Quantitative analysis of survival motor neuron copies: identification of subtle SMN1 mutations in patients with spinal muscular atrophy, genotype-phenotype correlation, and implications for genetic counseling. Am J Hum Genet 1999, 64:1340-1356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gérard B, Ginet N, Matthijs G, Evrard P, Baumann C, Da Silva F, Gerard-Blanluet M, Mayer M, Grandchamp B, Elion J: Genotype determination at the survival motor neuron locus in a normal population and SMA carriers using competitive PCR and primer extension. Hum Mutat 2000, 16:253-263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Feldkötter M, Schwarzer V, Wirth R, Wienker TF, Wirth B: Quantitative analyses of SMN1 and SMN2 based on real-time LightCycler PCR: fast and highly reliable carrier testing and prediction of severity of spinal muscular atrophy. Am J Hum Genet 2002, 70:358-368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ogino S, Leonard DGB, Rennert H, Wilson RB: Spinal muscular atrophy genetic testing experience at an academic medical center. J Mol Diagn 2002, 4:53-58 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ogino S, Leonard DGB, Rennert H, Ewens WJ, Wilson RB: Genetic risk assessment in carrier testing for spinal muscular atrophy. Am J Med Genet 2002, 110:301-307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chang JG, Hsieh-Li HM, Jong YJ, Wang NM, Tsai CH, Li H: Treatment of spinal muscular atrophy by sodium butyrate. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2001, 98:9808-9813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Andreassi C, Jarecki J, Zhou J, Coovert DD, Monani UR, Chen X, Whitney M, Pollok B, Zhang M, Androphy E, Burghes AH: Aclarubicin treatment restores SMN levels to cells derived from type I spinal muscular atrophy patients. Hum Mol Genet 2001, 10:2841-2849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barnard R, Futo V, Pecheniuk N, Slattery M, Walsh T: PCR bias toward the wild-type k-ras and p53 sequences: implications for PCR detection of mutations and cancer diagnosis. Biotechniques 1998, 25:684-691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Polz MF, Cavanaugh CM: Bias in template-to-product ratios in multi-template PCR. Appl Environ Microbiol 1998, 64:3724-3730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Warnecke PM, Stirzaker C, Melki JR, Millar DS, Paul CL, Clark SJ: Detection and measurement of PCR bias in quantitative methylation analysis of bisulphite-treated DNA. Nucleic Acids Res 1997, 25:4422-4426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mutter GL, Boynton KA: PCR bias in amplification of androgen receptor alleles, a trinucleotide repeat marker used in clonality studies. Nucleic Acids Res 1995, 23:1411-1418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Walsh PS, Erlich HA, Higuchi R: Preferential PCR amplification of alleles: mechanisms and solutions. PCR Methods Appl 1992, 1:241-250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu Q, Thorland EC, Sommer SS: Inhibition of PCR amplification by a point mutation downstream of a primer. Biotechniques 1997, 22:292-300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alvarez MJ, Depino AM, Podhajcer OL, Pitossi FJ: Bias inestimations of DNA content by competitive polymerase chain reaction. Anal Biochem 2000, 287:87-94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]