According to the Bylaws of the AACP, the Professional Affairs Committee is to study:

issues associated with the professional practice as they relate to pharmaceutical education, and to establish and improve working relationships with all other organizations in the field of health affairs. The Committee is also encouraged to address related agenda items relevant to its Bylaws charge and to identify issues for consideration by subsequent committees, task forces, commission, or other groups.

COMMITTEE CHARGE

President Rodney A. Carter charged the 2010-2011 American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy (AACP) Professional Affairs Committee with:

Examining how AACP and its members can most effectively partner with a variety of key stakeholders to accelerate the implementation of pharmacist services (e.g., MTM, primary care) as the standard for team-based, patient-centered care.

Members of the 2010-2011 Professional Affairs Committee include faculty from various colleges and schools of pharmacy as well as pharmacy practice association representatives from the American Pharmacists Association (APhA), the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP), the National Association of Chain Drug Stores (NACDS), and the National Community Pharmacists Association (NCPA). In order to fulfill the Committee charge, the Committee members met for a day and a half in Arlington, Virginia in October 2010 to discuss the committee charge and develop a plan of action to address the charge. Following this meeting, the Committee communicated via a series of conference calls as well as personal exchanges via telephone and email. The result is the following report which is positioned to discuss various models of care, challenges and opportunities pertaining to the charge, successful practices of AACP members and multiple pharmacy practice organizations, and recommendations to AACP in response to the Committee charge.

BACKGROUND

The pharmacy profession has been in transition from a product-based to a patient-centered care model since the introduction of the pharmaceutical care philosophy in the 1990s.1 This transition has been accomplished to varying degrees in different pharmacy practice settings and has been influenced by a variety of factors including the transition to the clinically-focused Doctor of Pharmacy (Pharm.D.) degree as the entry level degree and the increasing recognition that medication-related problems pose a significant threat to public health.2 The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) recognized the importance of medication therapy management (MTM) services by requiring all Medicare Part D plans to provide MTM as part of their programs.3 Recent healthcare reform (HCR) legislation includes provisions for MTM and pharmacist-provided services as part of integrated team-based care models designed to improve the quality of healthcare delivered in the United States.4 Pharmacists are well-positioned to serve as the medication therapy expert on the healthcare team.5

Currently, MTM services are not offered to all patients in all settings. This creates a situation of inequality and fragmentation of pharmacy services. It is imperative that the profession and the Academy accelerate the implementation of patient-centered, team-based care as the standard of pharmacy practice with the availability of MTM services to all patients. This vision has been clearly articulated in the Joint Commission of Pharmacy Practitioners (JCPP) vision for pharmacy practice.6 Identification of the factors that are impeding the realization of this vision and the development of strategies to accelerate its adoption as the standard of pharmacy practice in 2015 are the focus of this report. With the current HCR legislation, increasing the momentum for implementation of medication management services and chronic disease management services provided by pharmacists is a critical issue for pharmacy practice and education.

The policies of AACP support the transition to patient-centered care and encourage the collaborative relationships to facilitate this transition:

AACP supports the position that pharmacist-provided medication therapy management core elements are an essential and integral component of primary care. (Source: 2009-10 Argus Commission as revision to Professional Affairs Committee, 1994)

The mission of pharmacy education is to prepare graduates who provide patient-centered care that ensures optimal medication therapy outcomes and provides a foundation for specialization in specific areas of pharmacy practice; participation in the education of patients, other healthcare providers, and future pharmacists; conduct of research and other scholarly activity; and provision of service and leadership to the community. (Source: Academic Affairs Committee, 2007)

AACP supports research, education, and development of practice models to promote safe medication practices as the standard of care in all practice settings. (Argus Commission, 2007)

AACP endorses the competencies of the Institute of Medicine for health professions education and advocates that all colleges and schools of pharmacy provide faculty and students meaningful opportunities to engage in interprofessional education, practice and research to better meet health needs of society. (Source: Professional Affairs Committee, 2007)

AACP members should educate the public about the expanded scope of pharmacy practice and advocate for payment of services rendered. (Source: Council of Deans, 2003)

AACP supports interdisciplinary and interprofessional education for health professions education. (Source: Professional Affairs Committee, 2002)

AACP will support member colleges and schools in their efforts to develop pharmacy professionals committed to their communities and all the populations they serve, by facilitating opportunities for the development and maintenance of strong community-campus partnerships. (Source: Professional Affairs Committee, 2001)

AACP encourages its member colleges and schools to develop or enhance relationships with other primary care professions and educational institutions in the areas of practice, professional education, research, and information sharing. (Source: Professional Affairs Committee, 1994)

THE FUTURE OF PHARMACY PRACTICE

The JCPP is comprised of 11 national pharmacy practitioner organizations and works to address strategic issues facing the profession. In 2004, JCPP released the Future Vision for Pharmacy Practice, outlining the desired pharmacy practice model to be achieved by 2015.6 The JCPP vision states that “Pharmacists will be the health care professionals responsible for providing patient care that ensures optimal medication therapy outcomes.”6 It is envisioned that pharmacists in practice “will have the authority and autonomy to manage medication therapy and will be accountable for patients’ therapeutic outcomes. In doing so, they will communicate and collaborate with patients, caregivers, health care professionals, and qualified support personnel.”6 In 2007, JCPP organizations developed an action plan to implement the vision that includes focused activities on the practice models, payment models, and communications needed for pharmacists to practice in a patient-centered role.7 Integrating the activities outlined in the JCPP work plan within the evolving healthcare system will be necessary to realize the JCPP vision. Academic institutions have a significant role in making this plan a reality.

The passage of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act4 in 2010 brought a renewed focus on improving healthcare access, quality, safety, and cost to the nation. In order to contribute to this focus, health professionals are moving toward the core educational competencies outlined by the Institute of Medicine (IOM) in Health Professions Education: A Bridge to Quality.8 These competencies assert that all health professionals should be educated to deliver patient-centered care as members of an interdisciplinary team, emphasizing evidence-based practice, quality improvement approaches, and informatics.8

Interdisciplinary teams of healthcare professionals working to expand access, increase quality, and improve health outcomes are found in many models in healthcare and will continue to grow in the future. MTM services9 are often a component of these models and can lead to improvements in humanistic, economic and clinical outcomes for patients.5,10-13 Examples of patient-centered, integrated care models involving pharmacists in today's healthcare system include area health education centers (AHECs),14 academic health centers,15 the Veterans Administration (VA),16 Indian Health Service (IHS),17 and Kaiser Permanente Colorado.18 More than 50 colleges and schools of pharmacy have leveraged their resources to participate in the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) Patient Safety and Clinical Pharmacy Services Collaborative (PSPC).19 Through PSPC, federally-qualified health centers continue to develop into true medical homes providing comprehensive primary care services through an infrastructure that includes clinical pharmacy services. An important aspect of PSPC is a community-engaged approach to healthcare system organization.

The report of the 2009-2010 AACP Professional Affairs Committee thoroughly examined the integration of pharmacists in primary care and the role of academic pharmacy.20 The report contains an extensive appendix that summarizes 151 reports of evidence of the pharmacist's role in primary care. Another example, the Patient Centered Medical Home (PCMH), is an evolving model of interprofessional care that provides comprehensive primary care to adults, youth and children.21 In the PCMH, comprehensive medication management is the standard of care that ensures that each patient's medications are assessed to determine that each one is: appropriate for the patient, effective for the medical condition, safe given co-morbidities and concurrent medications, and able to be taken by the patient as intended.22

Many successful team-based care models occur in settings where pharmacists may or may not be physically located with physicians and other healthcare providers. In health systems, physician office settings, and community health centers, pharmacists work directly with prescribers to manage and monitor complex medication therapies. Pharmacists are the medication therapy experts on the team and can affect the delivery of care by addressing the challenges of MTM services.23 In addition to serving in a consultant role to healthcare providers, pharmacists in these settings schedule patient visits that involve medication education, chronic disease management, and health and wellness services. Where permitted by state practice acts, pharmacists working under collaborative practice agreements with physicians may initiate medication therapies, adjust medication dosages, monitor medications and order laboratory tests.24 In these settings, pharmacists have access to the medical diagnoses, laboratory values, and other information in patients’ medical records. Pharmacists lack access to such critical information in some settings (i.e., community pharmacy practice), although pharmacy professional organizations are working to ensure that the electronic health record (EHR) infrastructure will permit access by pharmacists.25 The Asheville Project26 and Diabetes Ten City Challenge27 are examples of programs that focus on pharmacists developing collaborative relationships with patients and prescribers in order to improve the use of medications and overall healthcare.

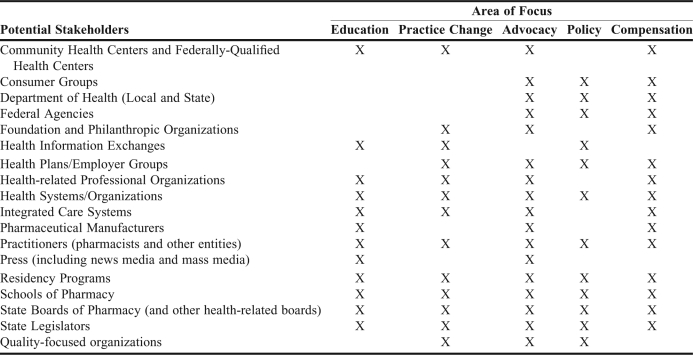

Ensuring that the pharmacy profession's future vision becomes a reality will require strong collaborations with key stakeholders and partners. Key themes for advancing the future of pharmacy practice include elements related to compensation, education, practice, advocacy, and policy. Table 1 provides an overview of where these focus areas and stakeholders may intersect. These key partners will assist in developing the framework for the future of our profession and constitute important stakeholders for the Academy.

Table 1.

Potential Stakeholders and Focal Areas for the Advancement of Pharmacist Services in Patient-Centered Care

Financial Considerations

Viable business model(s) for pharmacists’ patient care services are needed for broad expansion and acceleration in the adoption of these services in the marketplace. Pharmacists are currently receiving payment for Medicare Part D MTM services, state Medicaid programs, self-insured employers, and private sector programs.28,29 In integrated care settings, pharmacists’ salaries are often justified by the overall healthcare savings realized from their services by the entity. In the emerging medical home models and accountable care organizations (ACOs), compensation for patient care services provided by pharmacists remain to be determined. Potential payment options for pharmacists within these models include utilizing billing codes (i.e., Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes for pharmacist-provided MTM services, Evaluation and Management (E&M) CPT codes) as well as capitated payment methodologies and fee-for-service/self-pay by patients.30

Within any of the current and evolving models of patient care, payment for such services will include value and performance-based criteria. This system for compensation is a critical issue in many sectors of healthcare, including the PCMH. The Patient-Centered Primary Care Collaborative (PCPCC) has developed a framework, comprised of the following elements, for the payment structure for PCMH:31

It should reflect the value of physician and non-physician staff patient-centered care management work that falls outside of the face-to-face visit.

It should pay for services associated with coordination of care both within a given practice and between consultants, ancillary providers, and community resources.

It should support adoption and use of health information technology for quality improvement.

It should support provision of enhanced communication access such as secure e-mail and telephone consultation.

It should recognize the value of physician work associated with remote monitoring of clinical data using technology.

It should allow for separate fee-for-service payments for face-to-face visits. (Payments for care management services that fall outside of the face-to-face visit, as described above, should not result in a reduction in the payments for face-to-face visits).

It should recognize case mix differences in the patient population being treated within the practice.

It should allow physicians to share in savings from reduced hospitalizations associated with physician-guided care management in the office setting.

It should allow for additional payments for achieving measurable and continuous quality improvements.

Many of these aforementioned factors are potential areas of exploration for research and practice within pharmacy academia. Pharmacist services reimbursement within this new payment model is a needed area of exploration and assessment.

Policy Statement 1: AACP supports the efforts of colleges and schools of pharmacy working with healthcare entities to promote and advocate for the inclusion, reimbursement and sustainability of pharmacist services as a required element of patient-centered care in all settings. This policy statement was adopted by the AACP House of Delegates on July 13, 2011.

Recommendation 1: AACP should work in collaboration with other stakeholder organizations to develop standardization in patient care delivery models and payment systems to assure consistency of services across the United States.

Education Considerations

The vision for the future of practice outlined by JCPP and others can only be realized by embracing the continuum of education and training that is essential to preparing tomorrow's pharmacists. A number of factors are currently impacting on the educational enterprise. Careful consideration of these factors by academic pharmacy, accrediting agencies, and professional pharmacy organizations will be critical to achieving our desired future.

Interprofessional education: Once conceptually viewed as simply a good idea, interprofessional education is now becoming a reality in many educational institutions and is truly being embraced by the leadership of each healthcare discipline.32 In general, interprofessional education is built upon the tenets of collaboration, respectful communication, reflection, application of knowledge and skills, and direct patient care experience in interprofessional teams. Many pharmacy and other healthcare discipline programs are examining their curricula and making modifications to instill interprofessional education into the culture of their institution. Strong partnerships with the educational programs of other healthcare professions are essential to making interprofessional education possible. Ideally, these educational opportunities need to be incorporated as required curricular content in all healthcare professions early in the curriculum and not just as experiential opportunities within the last professional year. Institutional commitment to the incorporation of interprofessional courses is essential to assure that all schools modify their academic schedules to accommodate these offerings.

Postgraduate residency training: The recent growth of postgraduate residencies is laudable, but it has not kept pace with the increasing demand by pharmacy school graduates.33 Academic pharmacy can help reduce this shortfall34,35 and the return on investment can be beneficial on humanistic, educational, and economic levels.36 A robust effort to increase the number of Postgraduate Year 1 (PGY1) residency positions will assist in expanding and accelerating the development of patient-centered practice while also providing a more relevant experiential education experience reflecting the practice of the future. Similarly, more programs that offer specialized training through Postgraduate Year 2 (PGY2) residencies and fellowships are necessary. This will assist in providing a steady stream of practitioners who can meet the credentialing requirements of their practice setting.37 Obtaining specialty certification in a relevant practice area such as one or more of those offered by the Board of Pharmacy Specialties (BPS)38 after completion of a residency is becoming an increasingly important practice credential. Inclusion of postgraduate training in the budgets and financial planning of colleges and schools of pharmacy, as well as seeking co-funding opportunities via partner institutions and foundations, can greatly accelerate the growth of these programs.

Continuing professional development: Earning a doctor of pharmacy degree is but the first step in becoming a competent pharmacy practitioner. Continuing professional development (CPD) is a framework for lifelong learning that is a potential model for the pharmacy profession.39 It is an application for constant learning that extends beyond obtaining continuing education units (CEUs) necessary for pharmacist relicensure. Advanced knowledge, use of critical thinking skills, and effective evaluation of information about therapeutic entities and delivery systems are keys to ensuring that current and future practitioners remain competent to meet the growing complexities of care. CPD programs designed to provide practical skills in implementing patient-centered programs in various pharmacy settings are needed. Certificate programs in MTM and other areas have emerged to help re-tool the existing pharmacist workforce.40

Policy Statement 2: AACP supports member colleges and schools in their efforts to invest in the expansion of postgraduate residencies and fellowship programs that prepare pharmacists to be effective members of patient-centered healthcare teams. This policy statement was amended and adopted by the AACP House of Delegates on July 13, 2011 as “AACP supports member colleges and schools in their efforts to invest in the expansion of education and training programs that prepare pharmacists to be effective members of patient-centered healthcare teams.”

Suggestion 1: Colleges and schools of pharmacy should partner with healthcare academic institutions to provide interprofessional joint curricula, experiential programs, and/or service learning opportunities for future healthcare practitioners.

Suggestion 2: Colleges and schools of pharmacy should implement continuing professional development (CPD) programs that train practitioners in the practical steps to implement medication therapy management services in their practices and to create mentoring programs that provide suitable faculty role models.

Suggestion 3: Colleges and schools of pharmacy should recruit, develop, and retain faculty members specializing in providing pharmacist services in patient-centered care teams in all practice settings and to develop mechanisms to reward and recognize the value of these initiatives in faculty promotion criteria.

Suggestion 4: Colleges and schools of pharmacy should include within their budgets opportunities to develop pharmacy residencies in collaboration with other stakeholders.

Pharmacy Practice Considerations

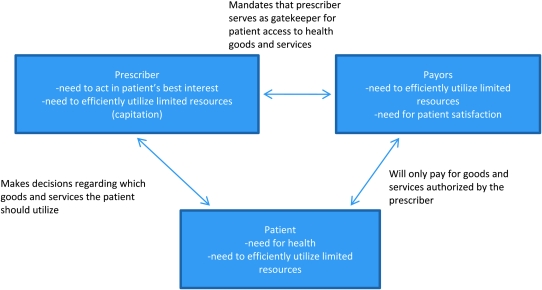

Consumer Readiness. MTM services provided by pharmacists are among the millions of goods and services available to consumers. The process consumers use to identify, evaluate and select goods and services can be better understood from the perspective of marketing. Marketing is defined by Kotler as “a social and managerial process by which individuals and groups obtain what they need and want through creating, offering and exchanging products of value with others.”41 Kotler's definition of marketing can be applied to consumer decisions to adopt any product, including MTM services provided by pharmacists. While it is natural for health professionals to think of patient needs and how they evaluate wants to choose the products they ultimately demand, the purchase of health goods and services are unique relative to most other products (See Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Developed by Zgarrick D, member of the 2010-2011 AACP Professional Affairs Committee.

Before MTM services can be widely adopted, one must consider whether and how they satisfy needs. Patients, prescribers and payers can each be thought of as consumers, as they each have underlying needs (Figure 1). Medications have long been used to satisfy patient needs for health. Any service that better assures their safe and effective use should help patients meet this need. Prescribers have needs to act in the best interests of their patients and to make the most of limited resources (particularly when they share the risks for patient resource utilization and health outcomes). Pharmacists have documented that MTM services improve patient outcomes, benefit prescriber practices, and meet payer needs to lower cost and improve patient satisfaction with the quality of their healthcare.12,25,42-45

Given that medication-related needs exist throughout the healthcare system, one may wonder why more pharmacists have not offered MTM services, or why more consumers have not demanded them. Some may point to pharmacists’ unwillingness to change practice models, while others note that regulations may limit pharmacists’ ability to implement new services. Kotler proposes a five-stage model for the consumer buying process, which includes recognizing a problem or need, searching for information, evaluating the alternatives, making a purchasing decision and post-purchasing behavior.46 Pharmacists, like any other marketer, must effectively address these marketing questions and concerns by promoting their services to consumers. Marketers of pharmacy goods and services often use a combination of promotional techniques depending on the characteristics of the consumer (patients, prescribers, payers) and the complexity of the messages they are trying to convey. For example, advertising is a good way to inform patients in a community about the immunizations available at their local pharmacy, whereas convincing prescribers and payers of the value of MTM services is often better done with a face-to-face visit.

While effective marketing can be used by pharmacists to create new opportunities to expand their role in providing direct patient care services, the ability of the profession to seize these opportunities and meet consumer demand will be determined in part by the readiness and willingness of pharmacists to provide advanced patient care services. The colleges and schools of pharmacy have a responsibility to ensure that future pharmacists are not only knowledgeable about new healthcare models, but also how to go about marketing, implementing and evaluating their role within such models. Pharmacy curricula should be focused on the business acumen of providing such pharmacist services as well as the clinical knowledge needed to participate in such models. Organizational cultures and new business models that support the provision of such services will also need to be in place.

Pharmacist Readiness. Surveys of individual pharmacists have indicated a growing awareness of MTM and an increased interest in taking on additional responsibility in providing patient care services.47,48 There is, however, no professional consensus on what qualification(s) pharmacists should have to provide such services. Some have called for residency training as a prerequisite for pharmacists involved in direct patient care.49,50 Others have noted that the entry-level Pharm.D. and the revamped professional pharmacy curriculum are designed to adequately prepare graduates to provide direct patient care.51 Thus, research into the appropriate education and training model for pharmacists providing direct patient care would be valuable.

Educated and trained pharmacy technicians are a necessary component in pharmacy practice to enable MTM trained pharmacists to be able to provide patient care services. While over 400,000 pharmacy technicians have earned the Pharmacy Technician Certification Board (PTCB) Certified Pharmacy Technician (CPhT) credential since 1995,52 there is no adopted standard for the education, training, and certification for these practitioners as there is for pharmacists.53 Standards for pharmacy technician education, training, and certification are important as pharmacists practice in an environment of growing complexity of medication use while continuing to focus on medication safety and patient care.

There are many indicators that pharmacists have embraced the implementation of MTM services. The 2010 APhA MTM Digest reports expansion and maturation in MTM services by pharmacists in several areas, particularly the number of patients treated and year-to-year stability in many aspects of MTM service provision.54 The reasons that were cited by pharmacists as being the most important in executing the decision to implement MTM services included having a responsibility as a healthcare provider, having the desire to satisfy patient health needs, and the realization that they could fulfill a need to improve health quality.54 Despite the significant challenges of lack of reimbursement models and inefficient workflow concerns, many pharmacists appear to be embracing the opportunities that MTM services can present.

Employer Readiness. The business model for most pharmacies is still rooted in product distribution, and this is one of the most significant factors impeding the widespread availability of MTM services. In 2009, full-time pharmacists reported spending an average of 55% of their workdays performing tasks related to dispensing, while devoting only 16% to direct “patient care services.”47 High prescription volume and, until recently, persistent shortages in the pharmacist workforce have limited the availability of pharmacists to provide services beyond dispensing. Increased per-capita prescription consumption and estimates that 91 to 116 million additional prescriptions will be written annually for the new beneficiaries of healthcare reform legislation will impose additional demands on pharmacist time. Delegating technical functions to highly-trained and certified pharmacy technicians, as well as the adoption of technology, will be key factors in liberating pharmacist time for patient care services.55 Research into new and emerging practice models will be important.

The participation of community pharmacies in the provision of MTM services is critical to its widespread adoption. While in the past there was little financial incentive for community pharmacies to change their dispensing-oriented business models, continued pressure from shrinking reimbursement and competition from alternative distribution models (i.e., mail order) have forced a reassessment of services beyond dispensing. Providing immunizations is one service that community pharmacies have demonstrated a willingness to embrace. A growing percentage of influenza vaccinations are being provided by pharmacists, with one national pharmacy chain publicizing its intention to have 100% of its pharmacists certified as immunizers.56 Immunization programs offer an excellent model for clinical service adoption because immunizations have an existing consumer demand and pharmacies receive adequate compensation. Although rules and regulations vary among states, pharmacists in all 50 states have authority to administer immunizations. An immunization program causes minimal disruption to pharmacy workflow, and programs are scalable and replicable across large and diverse pharmacy chains.

MTM, on the other hand, has not yet gained broad adoption in community pharmacies, and a number of barriers have been identified by survey.51 For one, MTM services have not been broadly available to patients. Medicare prescription drug plans (PDPs) have been the primary source of demand for MTM services, but rigid eligibility requirements have resulted in only 10% of the Medicare patient population being eligible to receive these services, and many patients are being served through telephonic delivery methods implemented by the PDP. In a 2009 survey by APhA, pharmacists cited inconsistent or inadequate compensation for services provided.57 Compensation for MTM services offered by PDPs varies widely, and the lack of uniformity in services available and billing requirements have limited the scalability and replicability of programs by community pharmacies. In addition, the time necessary to provide MTM services can disrupt other aspects of pharmacy workflow, especially when the patient case load is too low to justify hiring additional personnel and investing in necessary resources such as well-trained pharmacists and private counseling areas. Innovative practice models have evolved to meet these challenges. Some pharmacies employ a “hub-and-spoke” model wherein a pharmacist floats among pharmacies in a region providing services on a scheduled basis. Others have developed call centers and provide beneficiaries telephonic MTM services.56,58 Such services are likely to proliferate until demand reaches a level that engenders widespread adoption of face-to-face services. Academic pharmacy can assist community pharmacy practitioners in meeting the demand for MTM services as well as the education of pharmacist practitioner to market and deliver such services. In addition, academic pharmacy can increase the availability of MTM by advocating for its inclusion in any health plan provided to the employees of the college or school of pharmacy.

Policy Statement 3: AACP supports the creation of partnerships with other national pharmacy organizations to develop a framework to ensure an educated, trained, and certified pharmacy technician workforce to enable pharmacists to provide medication therapy management and other patient care services. This policy statement was adopted by the AACP House of Delegates on July 13, 2011.

Policy Statement 4: AACP encourages its member institutions to require course work that develops the management, business, and entrepreneurial skills necessary for pharmacists to succeed as members of patient-centered healthcare teams. This policy statement was amended and adopted by the AACP House of Delegates on July 13, 2011 as “AACP encourages its member institutions to offer course work that develops the management, business, and entrepreneurial skills necessary for pharmacists to succeed as members of patient-centered healthcare teams.”

Recommendation 2: AACP should develop practice-based research training programming and resources for pharmacy practice faculty.

Suggestion 5: Colleges and schools of pharmacy should work with community pharmacy organizations to implement medication therapy management and other patient care services by establishing residencies, co-funded faculty, and practitioner mentoring programs.

Suggestion 6: Colleges and schools of pharmacy should work within their institutions to discuss, demonstrate, and document the value of practice-based pharmacy research and disseminate the results.

Suggestion 7: Colleges and schools of pharmacy should develop and/or support practice-based research training programs for their faculty to advance scholarship.

Suggestion 8: Colleges and schools of pharmacy should initiate or participate in practice-based research networks (PBRNs).

Advocacy and Policy Considerations

As the pharmacy profession matures in its ability to provide direct patient care, it must acquire a louder voice in the collaborations, discussions and debate about healthcare reform. AACP has developed substantial outreach programs and strategies that are changing the way the public views the roles and abilities of today's pharmacy graduates.59 AACP also advocates to legislative and regulatory bodies on a national level for more widespread implementation of pharmacists’ services. As healthcare reform was unfolding, AACP contributed numerous examples of how community-campus partnerships bring value to healthcare and enhance access to the community-based services offered by pharmacists.60

AACP has been an integral part of the HRSA PSPC since its inception. AACP is working with approximately 100 other national pharmacy and healthcare organizations to bring advanced pharmacy services to every community in America. As the PSPC embarks on its third year in 2011, it consists of 128 multidisciplinary teams that have partnered with more than 350 organizations from 43 states to establish clinical pharmacy services as an integral component of patient-centered, interprofessional healthcare teams. These teams are managing a broad range of chronic conditions in various healthcare settings where medication therapy plays a vital role. Fifty-seven colleges and schools of pharmacy have participating team members working with 92 community health centers and 26 hospitals.61

The research of pharmacy faculty has also contributed greatly to the body of evidence demonstrating the value of patient care services delivered by pharmacists. In a meta-analysis of 298 studies examining the outcomes of pharmacist-provided direct patient care, pharmacists improved clinical outcomes in patients with diabetes, hypertension, and dyslipidemia.5 Medication adherence, patient knowledge, and quality of life were also improved. Beneficial economic outcomes have also been demonstrated, although those outcomes have been mixed.9 It is vitally important that such evidence be disseminated beyond our own profession and used by healthcare policy decision makers in the future as the healthcare system continues to evolve. In AACP's 2010 strategic plan, Critical Issue 4 is advocacy.62 The major focus of that issue is to develop plans to strategically position AACP to carry out its advocacy agenda to build recognition of member contributions to public health.

As individual institutions and faculty members, we must also “reawaken our personal role as advocates” for improved healthcare through pharmacy services.63 Although AACP advocates effectively at the national level, it does not have the strength of numbers required to perform similar activities in each state. State and local advocacy efforts therefore depend on individual AACP members working either alone or in groups with other like-minded pharmacy supporters.

Individual AACP members are indeed enhancing the recognition of the pharmacist's value to healthcare through proper medication use by virtue of their involvement in community health centers, homeless clinics, local public health departments, and other community organizations.64 Such recognition eventually leads healthcare providers, patients, and the public to expect pharmacists to be an integral, ongoing part of the medication management process. Policy makers need to hear even more examples of how the teaching, research, and service activities of pharmacy faculty members improve not only the education of future pharmacists but the health of the public.64

Suggestion 9: Colleges and schools of pharmacy should be proactive in leading and participating in state/local coalitions with other colleges/schools, pharmacy organizations and other associated organizations to create and sustain patient-centered pharmacy practice models and advocate for necessary legislative changes to the state pharmacy practice acts.

Suggestion 10: Colleges and schools of pharmacy should be proactive in forming and participating in state/local coalitions whose focus is to create, promote, and sustain education, practice, and research related to interdisciplinary team-based, patient-centered healthcare.

COLLEGES AND SCHOOLS OF PHARMACY SUCCESSFUL PRACTICES TO IMPLEMENT PHARMACISTS SERVICES IN TEAM-BASED, PATIENT-CENTERED HEALTHCARE

The Committee investigated the collaborations and programs that colleges and schools of pharmacy have with outside entities that have contributed to the implementation of pharmacists services for team-based, patient-centered care utilizing two methods: 1) disseminating a Call for Successful Practices to members of AACP, and 2) scanning the reports of the major national pharmacy organizations. The goal of this investigation was to collect information that AACP members can use to develop or enhance future partnerships and to understand the processes involved in establishing such partnerships.

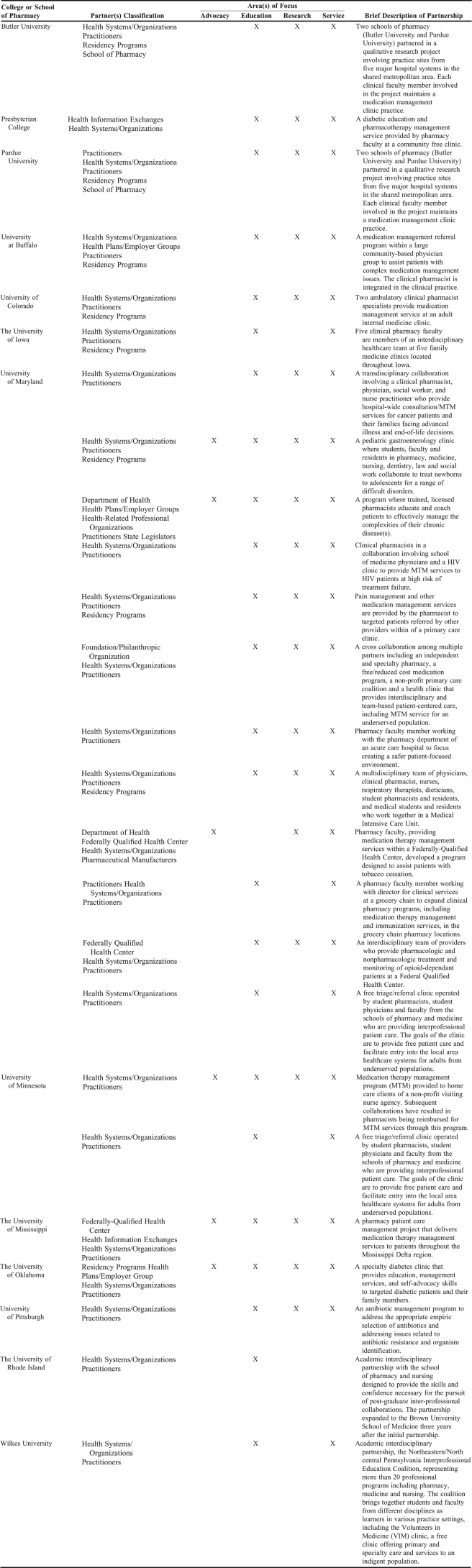

AACP Call for Successful Practices

A Call for Successful Practices for college/school involvement with partnerships contributing to the implementation of pharmacists’ services for team-based, patient-centered care65 was released to AACP membership in December 2010 using various mechanisms, including the AACP electronic newsletter and emails sent to the AACP Governance Council and Special-Interest Group listservs. Numerous reminders were sent out in January 2011. There were 23 responses to this call, representing 13 AACP member colleges and schools. An abbreviated version of responses from this call is presented in Appendix 1.

Many aspects discussed in the submissions represent challenges for colleges and schools of pharmacy contemplating collaborative pharmacist services. These include:

Justification for pharmacist services: This report has discussed many examples of the value of pharmacist services in patient-centered care and they should be referenced when having initial and ongoing conversations with potential partners. In addition, faculty at colleges and school of pharmacy should be well versed on the value and potential outcomes of such services.

Limitations of state pharmacy practice acts: Many of the services that pharmacists provide in patient-centered models may be in conflict with the state board of pharmacy act. In those instances, colleges and schools should work with their local and state pharmacy associations, state board of pharmacy, and other health provider groups to make the necessary revisions to the practice act.

Determination of compensation for the services provided by the pharmacist: There should be sufficient effort to determine the cost of the services to be provided by the pharmacist. Many payment models can be explored, such as colleges and schools sharing the cost with their partner(s), grants from foundations and other entities, and the pharmacist obtaining the required credentialing to bill for services. Compensation for pharmacist services is a necessary element to justify its value to the practice, patients, and profession.

Lack of access to patient records: This information provides vital data about the patient and the care being received. As the use of electronic health records (EHRs) becomes more prevalent, pharmacists and other healthcare providers will have to develop methods to ensure that the critical patient information is available when needed.

Practice workflow concerns: Pharmacists need sufficient space to perform services and sufficiently trained administrative and pharmacy technician staff. The committed partners must ensure that staff is aware of the services provided and the role of the pharmacist providing the services. This will ensure that everyone knows how their role affects or is affected by the pharmacist services.

Respondents to the call for successful practices shared a number of common elements. Many of the collaborations were initiated by the colleges and schools who decided to take a proactive and risk-sharing position to change practice. In other instances, the partnerships were started from previous professional affiliations, which made initiation of a partnership discussion less challenging. It is important that colleges and schools encourage, value and reward faculty to become involved in initiatives and programs involving many members of the healthcare team in order to facilitate networking and relationship-building. Maintaining open communication with all partners during the partnership formation is equally important. All partners should be involved in developing the program goals and outcomes. The role and services to be provided by the pharmacist should be clear, and the expected healthcare outcomes should be aligned with the goals of the health entity. Finally, these collaborations should have the potential to be used for student pharmacist practice experiences and residency programs. Many of partnerships have led to participation in other collaborations, such as the HRSA PSPC.19

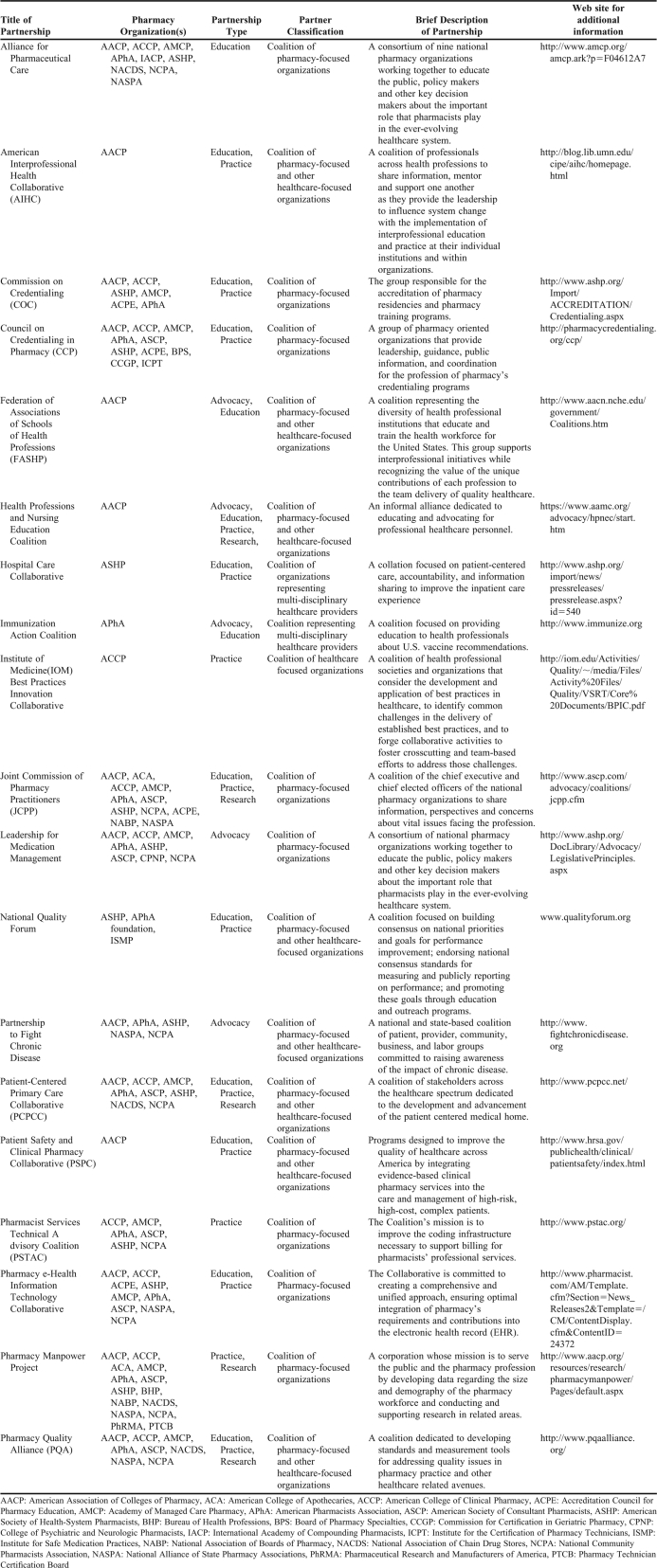

Scan of National Pharmacy Organizations

In order to gain a broader perspective on the partnerships that AACP and its member colleges and schools have created to implement pharmacists’ services as the standard for team-based, patient-centered care, the Committee contacted representatives from the American College of Clinical Pharmacy (ACCP), APhA, ASHP, NACDS, and NCPA to inquire about their involvement with such collaborations. Appendix 2 contains a brief description of the programs and initiatives involving colleges and schools and national pharmacy organizations. Many of these collaborations involve other members of the healthcare team, which is essential for realizing the goal of having pharmacist services in patient-centered models of care.

ELEMENTS FOR SUCCESSFUL COLLABORATIONS TO IMPLEMENT PHARMACISTS’ SERVICES IN TEAM-BASED, PATIENT-CENTERED HEALTHCARE

Collaborations to implement pharmacists’ services as the standard for team-based, patient-centered care will not occur if the pharmacy profession waits for other professions or healthcare entities to request or demand such services. Rather, the pharmacy profession must initiate the discussions about the value and need for such services based on the strength of the available evidence.

AACP members are in a unique position to pursue this dialogue. Colleges and schools of pharmacy have been instrumental in many projects demonstrating the positive outcomes of pharmacist services.5,10-13,21,26,27,42-45 Therefore, the evidence supporting the benefits of pharmacist-services is strong and readily available. Articulating these benefits to others both within and outside the pharmacy profession can help create demand for these services. Physician support for such services is often available on the campuses of colleges and schools of pharmacy, as well as within the surrounding communities.

Successful patient-centered collaborations require leaders who are committed to the process. Those who initiate the dialogue are often the ones who are present throughout the negotiation, implementation, and evaluation because they have the passion, enthusiasm and perseverance to work through the inevitable challenges that will arise. These leaders must be open-minded and knowledgeable about the healthcare systems being used to facilitate communication among providers and appropriate integration of services. They must work continuously with other healthcare professionals to develop and market services that will meet provider and patient needs. The support of the dean and other university administrators is critical for the success of these partnerships. In some cases, financial commitment/contributions from the colleges and schools are needed to initiate the collaboration.

It may take several years to implement pharmacist services in a team-based environment. Time-consuming steps include the initial planning, reaching consensus regarding mutual goals/objectives, development of a common mission and vision, defining roles and responsibilities, actually implementing the services, and subsequent monitoring and evaluation. Establishing timelines for major milestones will assist in these efforts. Written collaborative practice agreements, compensation systems, trained and efficient supportive personnel, and appropriate locations to provide services must be in place prior to implementation of pharmacy programs. Mechanisms for documenting pharmacist interventions and subsequent patient outcomes are also needed.

CONCLUSION

Collaborations are a necessary component of effective and efficient patient care programs. No single healthcare practitioner can meet all of the healthcare needs of patients. The collaborations reported in the literature, the call for successful practices, and the information from national pharmacy organizations confirm the need to work with organizations outside of pharmacy and healthcare to improve patient care and expand the scope of pharmacy practice.

The title of incoming AACP President Rodney Carter's speech during the 2010 AACP House of Delegates session was “The Stars are Aligning,” in which he referred to many opportunities for the Academy and the pharmacy profession to contribute to team-based, patient-centered healthcare. This report has examined the areas of opportunities and potential challenges to the implementation of such services. Colleges and schools of pharmacy have embraced the challenge of working with organizations within and outside of their institutions. A continuing commitment and rapid response are needed if pharmacy is to be an important participant in our evolving healthcare system. This review has demonstrated that the Academy has made tremendous strides to advance the pharmacy profession and create models demonstrating improvement in outcomes and healthcare savings. It is imperative to accelerate the replication of these services as the standard of pharmacy practice. Successful partnerships with other entities will ensure that the Academy will be able to expand in the areas of advocacy, education, practice and research to reach the most beneficial outcomes of patient-centered healthcare.

Appendix 1. Please see http://www.aacp.org/resources/education/Documents/Teams.pdf to access the full compendium of responses to the 2010-2011 Call for Successful Practices: College/School Involvement with Partnerships Contributing to the Implementation of Pharmacists’ Services for Team-Based, Patient-Centered Care.

Appendix 2. Colleges and Schools of Pharmacy and National Pharmacy Collaborations for the Advancement of Pharmacist Services in Patient-Centered Care

REFERENCES

- 1.Cipolle RJ, Strand LM, Morley PC. New York: McGraw Hill; 2004. Pharmaceutical Care Practice: The Clinician's Guide. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Institute of Medicine. Report Brief: Preventing Medication Errors. Washington, D.C.: Institute of Medicine; July2006. http://iom.edu/Reports/2006/Preventing-Medication-Errors-Quality-Chasm-Series.aspx. Accessed March 31, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 3.2010 Medicare Part D Medication Therapy Management (MTM) Programs Fact Sheet. http://www.cms.gov/PrescriptionDrugCovContra/Downloads/MTMFactSheet.pdf. Accessed March 31, 2011.

- 4.H.R. 3590-111th Congress: Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chisholm-Burns MA, Kim Lee J, Spivey CA, Slack M, Herrier RN, et al. US Pharmacists Effect as Team Members on Patient Care: Systematic Review and Meta Analysis. Med Care. 2010;48(10):923–933. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181e57962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Joint Commission of Pharmacy Practitioners (JCPP) JCPP 2015 Vision. Available at http://69.0.204.76/amcp.ark?p=1388AB1E. Accessed March 31, 2011.

- 7.An Action Plan for Implementation of the JCPP Future Vision of Pharmacy Practice. http://www.naspa.us/documents/jcpp/FINAL%20REPORT_JCPP%20Vision%20Action%20Plan_013108.pdf. Accessed March 31, 2011.

- 8.Greiner AC, Knebel E, editors. Institute of Medicine Committee on the Health Professions Education Summit. Health Professions Education: A Bridge to Quality. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Medication Therapy Management Services: A Critical Review. http://japha.metapress.com/media/4nc6a0bntj7xxk9chn2g/contributions/v/3/5/7/v3572307283778l2.pdf. Accessed March 31, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Chisholm-Burns MA, Graff Zivin JS, Kim Lee J, Spivey CA, Slack M, et al. Economic effects of pharmacists on health outcomes in the United States: A systematic review. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2010;67:1624–34. doi: 10.2146/ajhp100077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Oliveira DR, Brummel AR, Miller DB. Medication therapy management: 10 years experience in a large integrated health care system. J Manag Care Pharm. 2010;16(3):185–195. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2010.16.3.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carter BL, Rogers M, Daly J, Zheng S, James PA. The potency of team-based care interventions for hypertension – a meta analysis. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(19):1748–1755. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Isetts BJ, Schondelmeyer SW, Artz MB, Lenarz LA, et al. Clinical and economic outcomes of medication therapy management services: the Minnesota experience. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2008;48(2):203–211. doi: 10.1331/JAPhA.2008.07108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.National AHEC Organization. http://www.nationalahec.org/home/index.asp. Accessed March 31, 2011.

- 15.Draugalis JR, Beck DE, Raehl CL, Speedie MK, Yanchick VA, Maine LL. Call to Action: Expansion of Pharmacy Primary Care Services in a Reformed Health System. http://www.aacp.org/governance/COMMITTEES/argus/Documents/ArgusCommission09_10final.pdf. Accessed March 31, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Galt KA. Cost avoidance, acceptance, and outcomes associated with a pharmacotherapy consult clinic in a Veterans Affairs medical center. Pharmacotherapy. 1998;18:1103–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fisher R, Brands A, Herrier R. History of the Indian Health Service Model of Pharmacy Practice: Innovations in Pharmaceutical Care. Pharmacy in History. 1995;37(2):107–122. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Helling DK, Nelson KM, Ramirez JE, Humphries TL. Kaiser Permanente Colorado Region Pharmacy Department: innovative leader in pharmacy practice. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003) 2006 Jan-Feb;46(1):67–76. doi: 10.1331/154434506775268580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) Patient Safety and Clinical Pharmacy Services Collaborative (PSPC) Resources. http://www.hrsa.gov/publichealth/clinical/patientsafety/resources.html. Accessed March 31, 2011.

- 20.Haines SL, DeHart RM, Hess KM, Marciniak MW, Mount JK, Phillips BB, et al. Report of the 2009-2010 AACP Professional Affairs Committee. http://www.aacp.org/governance/COMMITTEES/professionalaffairs/Documents/PACReportFinalJulyBoard.pdf. Accessed March 31, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Patient-Centered Medical Home Collaborative. http://www.pcpcc.net/patient-centered-medical-home. Accessed March 31, 2011.

- 22.Patient-Centered Medical Home Collaborative: Medication Management. http://www.pcpcc.net/medication-management. Accessed March 31, 2011.

- 23.Smith MA, Bates DW, Bodenheimer T, Cleary PD. Why pharmacists belong in the medical home. Health Affairs. 2010;29(5):906–913. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.National Association of Boards of Pharmacy. Survey of Pharmacy Law 2010: National Association of Boards of Pharmacy. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pharmacy e-Health Information Technology Collaborative. http://www.pharmacist.com/AM/Template.cfm?Section=News_Releases2&Template=/CM/ContentDisplay.cfm&ContentID=24372. Accessed March 31, 2011.

- 26.Cranor CW, Bunting BA, Christensen DB. The Asheville Project: long-term clinical and economic outcomes of a community pharmacy diabetes care program. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2003;43:173–90. doi: 10.1331/108658003321480713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fera T, Bluml BM, Ellis WM. Diabetes ten-city challenge: Final economic and clinical results. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2009;49:383–91. doi: 10.1331/JAPhA.2009.09015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roberts BT. A Community Pharmacy Success in Medicare Part D Plan. http://ncpanet.wordpress.com/2010/01/28/a-community-pharmacy-success-in-medicare-part-d-plan/. Accessed March 31, 2011.

- 29.Shepherd MD, Richards KM, Winegar AL. Prescription drug payment times by Medicare Part D plans: Results of a national study. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2007;47:e20–e26. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Patient-Centered Medical Home Collaborative: Payment for Medication Management. http://www.pcpcc.net/content/payment-medication-management-services. Accessed March 31, 2011.

- 31.The Patient-Centered Primary Care Collaborative: Reimbursement Reform. http://www.pcpcc.net/reimbursement-reform. Accessed March 7, 2011.

- 32.Zwarenstein M, Reeves S, Barr H, Hammick M, Koppel I, Atkins J Interprofessional education: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2006 Issue 4 The Cochrane Collaboration. John Wiley and Sons, Ltd. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.American Society of Hospital Pharmacists. ASHP Resident Matching Program 2010. www.ashp.org/DocLibrary/Accreditation/ASD-Match2010.aspx. Accessed March 31, 2011.

- 34.Lee M, Bennett M, Chase P, Gourley D, Letendre D. Final Report and Recommendations of the 2002 AACP Task Force on the Role of Colleges and Schools in Residency Training. http://www.aacp.org/governance/councildeans/Documents/FinalTaskForceReportResidencies.pdf. Accessed March 31, 2011.

- 35.Schommer JC, Bonnarens JK, Brown LM, Goode JV. Value of community pharmacy residency programs: College of pharmacy and practice site perspectives. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2010;50:e72–388. doi: 10.1331/JAPhA.2010.09151. Doi.10.1331/JAPhaA.2010.09151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Smith KM, Sorensen T, Connor KA, Dobesh PP, et al. Value of conducting Pharmacy Residency Training—The Organizational Perspective. Pharmacotherapy. 2010;30(12):490e–510e. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Credentialing in Pharmacy. http://pharmacycredentialing.org/ccp/Files/CCPWhitePaper2006.pdf. Accessed March 31, 2011.

- 38.Board of Pharmacy Specialties. http://bpsweb.org. Accessed March 31, 2011.

- 39.The Council on Credentialing in Pharmacy Resource Document: Continuing Professional Development in Pharmacy. http://pharmacycredentialing.org/ccp/Files/cpdprimer.pdf. Accessed March 31, 2011.

- 40.Certificate Training Programs. http://www.pharmacist.com/Content/NavigationMenu3/ContinuingEducation/CertificateTrainingProgram/CTP.htm. Accessed March 31, 2011.

- 41.Kotler P. Marketing Management: Analysis, Planning, Implementation and Control (9th Edition). Prentice-Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ. p. 9.

- 42.Carter BL, Ardery G, Dawson JD, James PA, Bergus GR, Doucette WR, et al. Physician and pharmacist collaboration to improve blood pressure control. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(21):1996–2002. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Smith MA, Johnston PE. Cost justification of ambulatory clinical pharmacy services (Part 1) Tenn Pharmacist. 1983;19:26–8. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bunting BA, Smith BH, Sutherland SE. The Asheville Project: clinical and economic outcomes of a community-based medication therapy management program for hypertension and dyslipedemia. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2008;48:23–31. doi: 10.1331/JAPhA.2008.07140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Devine EB, Hoang S, Fisk AW, Wilson-Norton JL, Lawless NM, Louie C. Strategies to optimize medication use in the physician group practice: the role of the clinical pharmacist. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2009;49:181–91. doi: 10.1331/JAPhA.2009.08009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kotler P. Marketing Management: Analysis, Planning, Implementation and Control (9th Edition). Prentice-Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ. p. 192.

- 47.Law AV, et al. Ready, willing, and able to provide MTM services? A survey of community pharmacists. Research in Social & Administrative Pharmacy. 2009;5:376–81. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2009.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Doucette WR, Gaither CA, Kreling DH, et al. Final Report of the 2009 National Pharmacist Workforce Survey. 2010. http://www.aacp.org/resources/research/pharmacymanpower/Documents/2009%20National%20Pharm20Pharmacist%20Workforce%20Survey%20-%20FINAL%20REPORT.pdf. Accessed March 31, 2011.

- 49.Murphy JE, Nappi JM, Bosso JA, et al. American College of Clinical Pharmacy's vision of the future: postgraduate pharmacy residency training as a prerequisite for direct patient care practice. Pharmacotherapy. 2006;26:722–33. doi: 10.1592/phco.26.5.722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Policy position 0701: requirement for residency. www.ashp.org/DocLibrary/BestPractices/policypositions2009.aspx.

- 51.Bright DR, et al. The Mandatory Residency Dilemma: Parallels to Historical Transitions in Pharmacy Education. Ann Pharmacother. 2010;11:1793–99. doi: 10.1345/aph.1P394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.PTCB Press Release: Record Number of Pharmacy Technicians Seek Certification through PTCB. https://www.ptcb.org/AM/Template.cfm?Section=Press_Releases1&TEMPLATE=/CM/ContentDisplay.cfm&CONTENTID=3974. Accessed March 31, 2011.

- 53.Manasse Jr. HR, Menighan TE. Single standard for education, training, and certification of pharmacy technicians. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2010;50:116. doi: 10.1331/japha.2010.10508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.American Pharmacists Association. Medication Therapy Management Digest: Tracking the Expansion of MTM in 2010: Exploring the Consumer Perspective. http://www.pharmacist.com/AM/Template.cfm?Section=MTM&TEMPLATE=/CM/ContentDisplay.cfm&CONTENTID=25712. Accessed March 31, 2011.

- 55.Wilson D. Review of tech-check-tech. J Pharm Technol. 2003:159–69. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Institute of Medicine. The National Academies Press; 2010. The 2009 H1N1 Influenza Campaign. Summary of a Workshop Series. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.American Pharmacists Association. Medication Therapy Management Digest: Perspectives on 2009: A Year of Changing Opportunities. March 2010. http://www.pharmacist.com/AM/Template.cfm?Section=Home2&TEMPLATE=/CM/ContentDisplay.cfm&CONTENTID=22674. Accessed March 31, 2011.

- 58.Woldt J. Rite Aid takes a big step forward in patient care. Chain Drug Review. July 4, 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lang WG. Strength-based advocacy: making a difference through teaching, research, and service. Am J Pharm Educ. 2006;70(3):Article 63. doi: 10.5688/aj700363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lang WG. Focusing the academy's strengths to reorganize healthcare. Am J Pharm Educ. 2009;73(6):Article 113. doi: 10.5688/aj7306113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration. PSPC Teams. http://www.hrsa.gov/publichealth/clinical/patientsafety/teams.html. Accessed March 31, 2011.

- 62.American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy. Alexandria, VA: 2011. Strategic Plan. http: //www.aacp.org/about/Pages/StragegicPlan.aspx. Accessed March 31, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lang WG. Musings on America's birthday. Am J Pharm Educ. 2008;72(4):Article 82. doi: 10.5688/aj720482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lang WG. Strength-based advocacy: making a difference through teaching, research, and service. Am J Pharm Educ. 2006;70(3):Article 63. doi: 10.5688/aj700363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.2010-2011 Call for Successful Practices. http://www.aacp.org/resources/education/Pages/SuccessfulPracticesinPharmaceuticalEducation.aspx. Accessed March 31, 2011.