Abstract

Objectives. To evaluate faculty members’ and students’ perceptions of study strategies and materials.

Methods. Focus groups were conducted with course directors and first- and second-year students to generate ideas relating to use of course materials, technology, class attendance, and study strategies for mastering class concepts.

Results. Students and faculty members differed in their opinions about the utility of textbooks and supplemental resources. The main learning method recommended by students and faculty members was repeated review of course material. Students recommended viewing classroom lectures again online, if possible. Course directors reported believing that class attendance is important, but students based their opinions regarding the importance of attendance on their perceptions of lecture and handout quality. Results did not differ by campus or by student group (first-year vs. second-year students).

Conclusions. Students and faculty members have differing opinions on the process that could influence learning and course design. Faculty members should understand the strategies students are using to learn course material and consider additional or alternative course design and delivery techniques based on student feedback.

Keywords: technology, focus group, learning, course design

INTRODUCTION

With the availability of technology and a new generation of learners, higher education is changing.1 The availability of online courses, degrees, and learning tools has made traditional, live lectures and traditional textbooks no longer essential to learning. However, faculty members may be reluctant to embrace new technology and teaching methods, such as online learning or team-based learning, and may not have an understanding of students’ learning strategies and approaches to mastering course material.

Students and faculty members may have differing opinions about the learning process and recommended course materials that could influence learning and course design. A previous study involving physical therapy students found no difference in learning style and course success but did find improved understanding and demonstration of clinical concepts with the use of technology to enhance learning.2 An anatomy course found that lower-performing students used computer resources less frequently.3 Learning approach research conducted among Australian pharmacy students concluded that students prefer vocationally related teaching strategies, where course material could be applied in the professional setting.4,5 Another study characterized student pharmacists’ perceptions of testing, study strategies, and recall.6 Garavalia and colleagues compared student pharmacists’ perceptions of motivation and learning strategies at different points in the curriculum.7 They concluded that first-year students were more externally motivated than were third-year students, who relied more on intrinsic material that could be applied in the professional setting.7 Literature on student and faculty member perceptions of specific study strategies and materials is scarce.

Focus groups have been useful in providing insight on specific topics.8,9 They can be used to gather opinions outside of consensus, provide detailed information on student perceptions, clarify research findings or design subsequent research, and inform program pre-planning, reconfiguration, and assessment.8,9

The University of Tennessee College of Pharmacy (UTCOP) conducts synchronous distance learning between the Memphis and Knoxville campuses for 3 semesters starting in the second year. Didactic lectures and select recitations for required courses are recorded using Mediasite (Sonic Foundry, Madison, Wisconsin) and are posted on a secure Web site. At UTCOP, an audience response system, TurningPoint 2008 (Turning Technologies, Youngstown, Ohio), is used in the didactic portion of the curriculum for feedback during lectures and recitation sessions, attendance, and graded activities.

The purpose of this study was to characterize and compare faculty member and student perceptions of study strategies and materials. Focus groups were conducted to generate ideas relating to use of course materials, technology, class attendance, and study strategies for mastering class concepts.

METHODS

Previously published focus-group methodology was followed.8,9 Students were randomly selected to participate in the focus group based on campus involvement, leadership positions, cumulative grade point average, and campus location. All course directors on the Memphis and Knoxville UTCOP campuses were invited to participate in the faculty focus group. Each invited participant received an e-mail describing the project goals, the investigators’ names (1 Memphis faculty member, 1 Knoxville faculty member, and 1 fourth-year student), potential focus group members, and notification that the discussions would be audio recorded.

Focus groups were conducted separately with the faculty group composed of course directors on both campuses and 2 student groups stratified by year for the first- and second-year students. Each session was conducted simultaneously between the Memphis and Knoxville campuses in April and June 2010 and led by the student investigator. The faculty investigators served only as observers during all focus group sessions. At the time of the study, none of the students in the focus group were enrolled in either of the faculty investigators’ courses. Demographic information about all participants was collected anonymously during the focus group sessions and analyzed in a relational database.

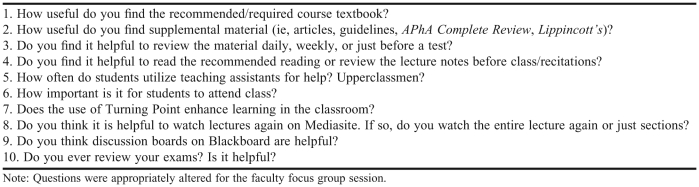

During the 75-minute focus groups, participants were asked to provide their perceptions about how courses are successfully completed by answering 10 predetermined questions (Table 1). Focus group questions were determined based on a preliminary e-mail survey tool administered to students who had successfully completed the first and second years of the professional curriculum. The survey instrument solicited strategies for successful course completion for each course in the first and second years of the curriculum. Open-ended questions pertaining to student learning techniques and resources were assessed for themes and used to generate questions for the focus groups. Major trends emerging from this assessment included class attendance, regular review of course materials, use of recommended readings and textbooks, use of TurningPoint software, questions by classroom instructors, seeking assistance from upperclassman, and review of lectures on Mediasite. Despite not being mentioned in the survey tool, additional questions pertaining to teaching assistants, examination review, and use of Blackboard (Blackboard, Inc.,Washington, DC) discussion boards were included because faculty members perceived these strategies to be useful for student learning.

Table 1.

Questions Asked of Student and Faculty Member Focus Groups

In all focus groups, each question was read to the entire group, and participants were invited to state their opinions. General questions on course materials and student success were presented first, followed by more detailed questions on classroom attendance and use of technology (eg, TurningPoint and Mediasite).9 Similar questions were grouped together. Students and faculty members were not required to respond to any question but were encouraged to comment even if they were not in consensus with the group. Each focus group session was recorded to aid in identifying responses with consensus between faculty members and students, but names were not recorded with any responses.

The student investigator acted as moderator and the 2 faculty investigators as assistant moderators. The moderator initiated and kept the discussion focused, subtracted and added questions following the direction of the dialogue, and sought clarification as time permitted. The assistant moderators, one located at each campus, were observers and note takers who also monitored the technology throughout the session. After each focus group session was completed, the moderator and assistant moderators discussed the success of each focus group and general themes were assessed. The moderator transcribed the responses and common themes were grouped together.

This project was granted exempt status by the University of Tennessee Investigational Review Board. All participants provided informed consent.

RESULTS

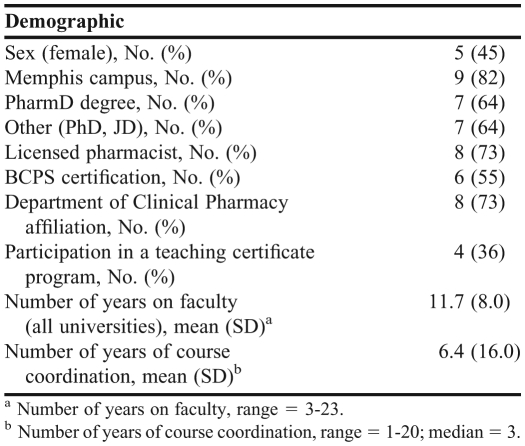

The demographics of focus group participants (students n = 15, faculty n = 11) are detailed in Tables 2 and 3. The majority of participants in both the faculty and student groups were male and located on the Memphis campus. Student participants were high achieving in all facets of professional education, including academics, leadership, and professional involvement. Faculty participants were experienced course directors with a mean of 6 years of course coordination. More than two-thirds were licensed pharmacists in the department of clinical pharmacy, with the majority (75%) being board-certified pharmacotherapy specialists.

Table 2.

Demographics of Student Focus Group Participants

Table 3.

Demographics of Faculty Focus Group Participants (N = 11)

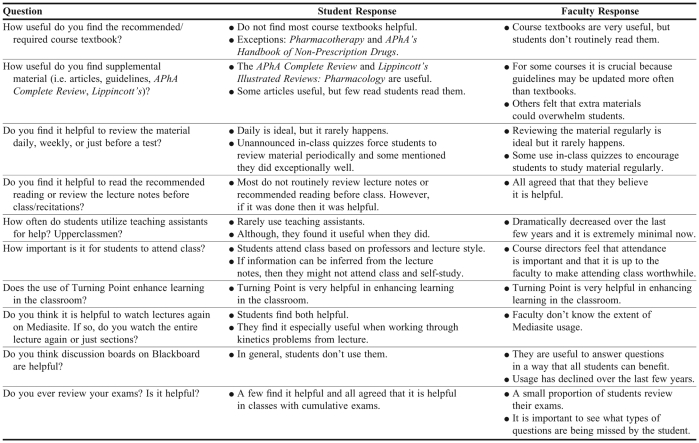

Table 4 provides a comparison of the student and faculty focus group responses. In general, students and faculty members agreed that regular review of material and quizzes is a potential strategy for course mastery. Students and faculty members agreed that Turning Point enhanced learning by maintaining student engagement, providing immediate feedback, and reinforcing concepts.

Table 4.

Comparison of Faculty and Student Focus Group Responses

Students generally did not use the required course textbook(s) with some exceptions (ie, Therapeutics, Self-Care and Nonprescription Drugs). Compared with second-year students, fewer first-year students found the mandatory textbooks useful. With the exception of clinical practice guidelines, students rarely used supplemental articles but frequently used other non-recommended review books.

Students expressed a preference for engaging lectures but still expect all pertinent information to be included in handouts. Although course directors stated that attendance was important, for some students, the instructor providing a detailed handout may have decreased the likelihood that they would attend class. The main learning method recommended by students was to review the course material regularly. Although second-year students recommended viewing classroom lectures again on Mediasite, they reported selectively viewing key segments rather than the entire lecture. They described the utility of viewing pharmacokinetic recitations on Mediasite because the recording could be paused while each section of the problem was worked. Students also stated that while they want to learn for long-term success, they focus their studying on material included on examinations. Faculty members agreed that students want to be successful on examinations and perceived that students prioritize successful course completion. However, faculty members want students to learn for long-term success. Although the groups agreed that examination review is helpful, especially in courses with cumulative examinations, faculty members reported that only a small percentage of students reviews their previous examinations. Finally, there was consensus among all groups that, in general, students rarely seek help from teaching assistants or review their examinations and that the use of these resources continues to decrease. Results did not differ by campus or by student group (first-year vs. second-year students).

DISCUSSION

The results of this study can help increase student pharmacists’ and faculty members’ understanding of the strategies and materials that are most useful in mastering the didactic curriculum. For example, although faculty members perceive that students should find discussion boards useful for posting questions and accessing faculty member responses, students generally do not use them. Perceptions regarding the usefulness of course textbooks also were discordant between faculty and student focus groups. Although students perceived a few course textbooks, such as Self-Care and Nonprescription Drugs, to be useful, it is questionable whether students are using these textbooks to supplement information provided in course lectures or to complete course assignments or online quizzes. Faculty members also continue to provide supplemental course materials, although students rarely use them. Both groups recommended that regularly reviewing course material was essential for course mastery and agreed on the value of the audience response system to enhance engagement and learning through recall and immediate feedback. These findings are consistent with other literature describing the use of this technology in schools and colleges of pharmacy.10-12

This is the first paper in the pharmacy education literature to discuss specific study strategies and materials, but our results are consistent with those in the non-pharmacy literature. A study of dental students found that learning tools provided by faculty members and outside references were equally helpful.13 A study in undergraduate economics and accounting courses found that offering extra credit as an incentive for students to document their reading led to high textbook use.14 However, another study that did not incentivize students found that less than 20% of undergraduate students used course textbooks.15 Both studies found that higher-achieving students used textbooks more often and read the text more in depth than lower-achieving students.14,15

Our study has several limitations. We defined course mastery as learning and retaining concepts in the course and achieving a satisfactory grade (by the student's definition). A satisfactory grade is subjective and uniquely defined by each student within each course. We did not correlate teaching effectiveness to course mastery as measured by academic performance (ie, grades). While student participant lists were randomly generated to select students with varying academic and leadership skills, participation was optional; thus, the students who agreed to participate may have been those who were the most motivated and outgoing. However, based on our experience, the majority of students are involved in student organizations and hold leadership positions, and approximately two-thirds of the students are at the Memphis campus, which correlates with the demographics of the student focus groups. Similarly, the majority of enrolled students are admitted with undergraduate degrees. Therefore, we believe that the demographics of the student focus groups are consistent with the overall student body of UTCOP.

CONCLUSION

The implications of this study are for faculty members to understand the strategies students are using to learn course material. Faculty members may not always accurately perceive student practices and study techniques. Based on the incongruity of student and faculty member opinions regarding the utility of course materials, such as textbooks, faculty members may want to consider additional or alternative course materials based on student feedback. Use of technology, such as recording lectures and using an audience response system, should also be encouraged. Future student pharmacists can use this information to guide their use of technology, course materials and other resources to help them master the didactic curriculum.

Acknowledgements

This project was presented in part as a poster presentation at the 2010 AACP annual meeting in Seattle, Washington.

REFERENCES

- 1.Blouin RA, Riffee WH, Robinson ET, et al. Roles of innovation in education delivery. Am J Pharm Educ. 2009;73(8):Article 154. doi: 10.5688/aj7308154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith AR, Cavanaugh C, Jones J, Venn J, Wilson W. Influence of learning style on instructional multimedia effects on graduate student cognitive and psychomotor performance. J Allied Health. 2006;35(3):e182–e203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rizzolo LJ, Aden M, Stewart WB. Correlation of web usage and exam performance in a human anatomy and development course. Clin Anat. 2002;15(5):351–355. doi: 10.1002/ca.10045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith L, Saini B, Krass I, Chen T, Bosnic-Anticevich S, Sainsbury E. Pharmacy students’ approaches to learning in an Australian university. Am J Pharm Educ. 2007;71(6):Article 120. doi: 10.5688/aj7106120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith L, Krass I, Sainsbury E, Rose G. Pharmacy students’ approaches to learning in undergraduate and graduate entry programs. Am J Pharm Educ. 2010;74(6):Article 106. doi: 10.5688/aj7406106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hagemeier NE, Mason HL. Student pharmacists’ perceptions of testing and study strategies. Am J Pharm Educ. 2011;75(2):Article 35. doi: 10.5688/ajpe75235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garavalia LS, Scheuer DA, Carroll CA. Comparative analysis of first- and third-year pharmacy students’ perceptions of student-regulated learning strategies and motivation. Am J Pharm Educ. 2002;66(3):219–223. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Instructional Assessment Resources. http://www.utexas.edu/academic/ctl/assessment/iar/programs/plan/method/focus.php. Accessed October 1, 2011.

- 9.Krueger RA. Focus Group Kit 3. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Inc; 1998. Developing questions for focus groups; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Medina MS, Medina PJ, Wanzer DS, Wilson JE, Nelson E, Britton ML. Use of an audience response system (ARS) in a dual-campus classroom environment. Am J Pharm Educ. 2008;72(2):Article 38. doi: 10.5688/aj720238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cain J, Robinson E. A primer on audience response systems: current applications and future considerations. Am J Pharm Educ. 2008;72(4):Article 77. doi: 10.5688/aj720477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cain J, Black EP, Rohr J. An audience response system strategy to improve student motivation, attention, and feedback. Am J Pharm Educ. 2009;73(2):Article 21. doi: 10.5688/aj730221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gerzina TM, Worthington R, Byrne S, McMahon C. Student use and Perceptions of different learning aids in a problem-based learning (PBL) dentistry course. J Dent Educ. 2003;67(6):641–653. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fitzpatrick L, McConnell C. Student reading strategies and textbook use: an inquiry into economics and accounting courses. Res High Educ J. Rockhurst University. http://www.aabri.com/manuscripts/09150.pdf. Accessed October 1, 2011.

- 15.Schneider A. Can plot improve pedagogy? novel textbooks give it a try. Chron High Educ. 2001;47(35):A12–A14. [Google Scholar]