Summary

Background

The phosphaturic mesenchymal tumor of the craniofacial sinuses (mixed connective tissue variant) is an extremely rare, distinctive paraneoplastic syndrome that is frequently associated with oncogenic osteomalacia.

Methods

In this report is presented a case of 22 years old man indicated four years of progressive generalized pain and weakness, eventually becoming wheel-chair bound. His current presentation was for chest pain resulting from atraumatic rib fractures.

Results

Imaging showed osteoporosis and multiple insufficiency fractures. CT and MRI showed an ethmoid mass. He had no symptoms referable to his nose or sinuses.

Conclusions

The ethmoid lesion was completely excised, the patient’s laboratory parameters returned to normal levels and the patient’s symptoms disappeared.

Keywords: phosphaturic mesenchymal tumor, oncogenic osteomalacia, insufficiency fracture, diagnostic imaging

Introduction

Phosphaturic mesenchymal tumor (PMT) is an uncommmon tumor that may cause oncogenic osteomalacia (1–6). This is due to an over expression of fibroblast growth factor-23 (FGF-23), a recently described protein capable of inhibiting renal tubular phosphate transport (6). Patients usually complain of a long history of bone pain and muscle weakness, often being so severely affected that they are unable to walk and become wheel-chair bound. We describe herein the radiological imaging and the clinic-pathologic features of a rare case of PMT which involved the craniofacial sinuses of the skull base.

Case report

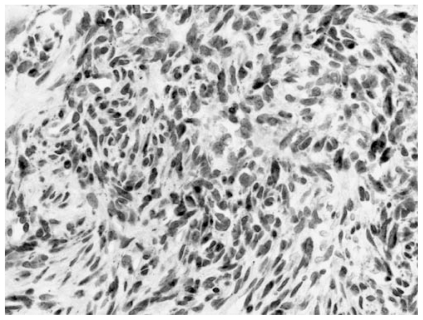

A 22-year-old man who had been wheel-chair bound for one year and prone to atraumatic fractures for two years, was admitted to the hospital. The patient had no past medical history of note and no abnormality on physical examination. Laboratory investigations revealed hypophosphatemia, hyperphosphaturia, normocalcemia, normocalciuria, elevated alkaline phosphatase, and normal serum levels of parathormone and osteocalcin. Skeletal radiographs revealed homogeneus and fuzzy appearance due to the decline of contrast differences between bone marrow and calcified bone and bone scintigraphy findings were suggestive of osteomalacia. On computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance (MR) imaging, a tumor was discovered at the vault of the rhinopharynx, involving the ethmoid and sphenoid sinuses (Figures 1–5). The tumor was surgically removed. Histologically, the tumor was initially diagnosed as a perivascular myoid tumor and subsequently reclassified as a variant of a sinonasal hemangiopericytoma-like tumor (Figures 6–8). Immunostain for fibroblast growth factor FGF-23 protein was positive (Figure 9). Post-surgery, the patient’s metabolic disturbances persisted and further imaging revealed a residual tumor. A second surgical procedure was performed and with complete removal of the tumor, the patient’s laboratory parameters returned to normal levels and the symptoms disappeared.

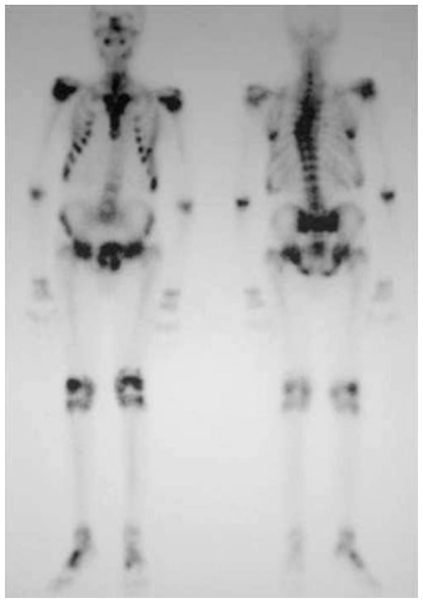

Figure 1.

Whole body bone scintigraphy (anterior and posterior views) shows multiple areas of increased uptake in the thoracic spine, ribs, pelvis and limbs. Note the characteristic H-shaped pattern in the sacrum, typical of insufficiency fractures.

Figure 2.

Frontal pelvic radiograph shows generalized osteopenia, and insufficiency fractures of the femoral neck and pubic rami bilaterally (white arrows) with decline of contrast differences between bone marrow and calcified bone due to the increased density of unmineralized osteoid.

Figure 3.

Frontal radiograph of both feet shows generalized osteopenia and multiple insufficiency fractures (white arrows) with homogenous and fuzzy overall radiographic appearance.

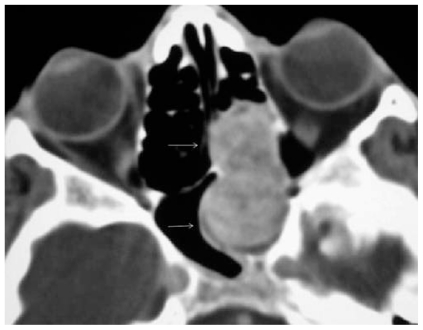

Figure 4.

Contrast-enhanced axial CT image shows a bulging enhancing tumor (white arrows) arising from the left ethmoid sinus.

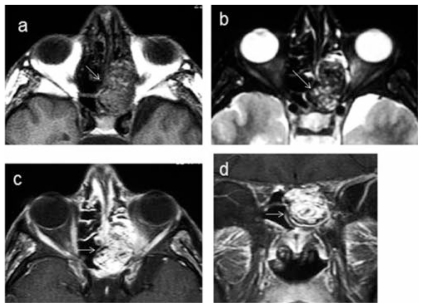

Figure 5.

a Axial T1-W, b axial T2-W, and contrast-enhanced, c axial T1-W and d coronal T1-W·MR images show a heterogenous tumor arising from the left sinus (white arrows). It is of mixed hypo-, iso- and hyperintense signals on both T1- and T2-weighted images, and shows marked heterogeneous enhancement.

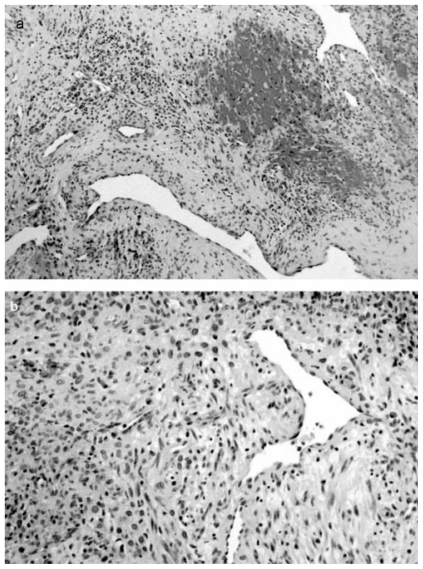

Figure 6.

a Characteristic histomorphologic features of a mesenchymal tumor with prominent, partly ramified, vascularization. Oval to spindle tumor cells are embedded in a collagenized to myxoid matrix. An associated mixed inflammatory mononuclear infiltrate is also present, and hemorrhages as well as hemosiderin deposits are visible. b Architectural and cytological details of the tumor (Hematoxylin and Esosin, Original magnification, a: ×120, b: ×240).

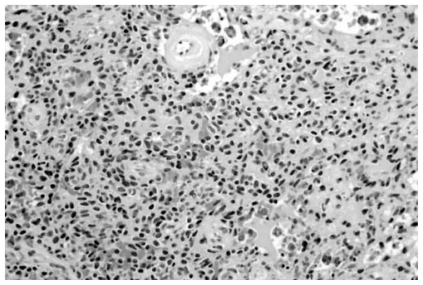

Figure 7.

The tumor showed a variety of cellularity and growth patterns. The neoplastic cells in this illustration show a more oval to round appearances. Top center: a small vessel with perivascular hyalinization is seen (Hematoxylin and Eosin, Original magnification, × 240).

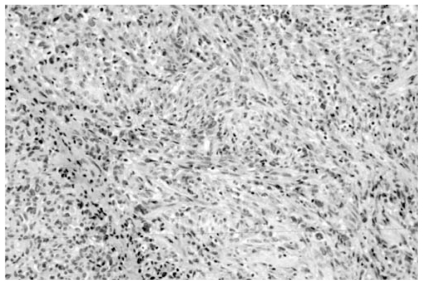

Figure 8.

Fascicular to almost storiform-whorled of the same tumor in a different field (Hematoxylin and Eosin. Original magnification, × 240).

Figure 9.

Immunostain for fibroblast growth factor-23 (FGF-23). Most tumor cells are positive, exhibiting an almost diffuse dark staining of the cytoplasm. (Immunoperoxidase. Diaminobenzidine, nuclear counterstain with Hematoxylin. Original magnification, × 410).

Discussion

We report a rare location of a PMT involving the craniofacial sinuses of the skull base. The typical laboratory findings secondary to phosphate loss are hypophosphatemia and hyperphosphaturia, which finally result in an inadequate mineralization of osteoid in mature bone, a metabolic disorder known as osteomalacia. Oncogenic osteomalacia is dramatically cured by tumor removal but when the tumor is not detected this condition can respond to 1,25 dihydroxyvitamin and phosphate supplementation. Phosphaturic mesenchymal tumor is usually located in soft tissue, but intraosseus as well sinonasal locations are also on record. Histologically, it corresponds to a polymorphous group of neoplastic entities (1–5), the most common of which is the so-called “mixed connective tissue type” (1–6), which is characterized by a distinctive admixture of bland spindled cells, osteoclast-like giant cells, microcysts, prominent and variously sized vasculature, smudgy to calcified cartilage-like matrix, and metaplastic bone. Other histological types of phosphaturic mesenchymal tumors are the osteoblastoma-like tumor, the non-ossifying fibroma-like tumor and the ossifing fibroblastoma-like tumor. Some cases have histological features of malignancy (6).

To date, a total of 142 cases are on record in the literature (7), of which only 11 cases were located in the nasal fossa and craniofacial sinuses (Table 1).

Table 1.

Reported cases of phosphaturic mesenchymal tumors located in the nasal fossa and craniofacial sinuses (8–16).

| Reference | Age (yr)/Sex | Site | Histologic Appearance | Outcome | Original Diagnosis | Suggested Revised Diagnosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Linsey 1982(8) | 54F | Nasopharynx | Uniform small spindled cells, giant cells, many small blood vessels, small bone islands | ANED, normal chemistry | Nasal angiofibroma | PMTMCT |

| Weidner and Santa Cruz 1987(9) | 35F | Maxillary sinus | Typical PMTMCT | ANED, normal chemistry | PMTMCT | PMTMCT |

| Papotti 1988(10) | 38F | Nasal cavity | Microcystic, bland spindled cells, granular eosinophilic material, many HPC-like vessels | ANED, normal chemistry | HPC-like/microcystic | PMTMCT |

| Wilkins 1992(11) | 55M | Maxillary sinus | HPC-like neuroendocrine marker negative, rare granules | ANED, normal chemistry | Paraganglioma | Sinonasal HPC-like tumor |

| Gonzalez Compta 1998(12) | 69F | Ethmoid sinus | Typical PMTMCT | Dead surgical complications | PMTMCT | PMTMCT |

| Ohashi 1999(13) | 43M | Maxillary sinus | Round cells with dilated vascular spaces | ANED, normal chemistry | Hemangiopericytoma-like tumor | Sinonasal hemangio Pericytoma |

| Clunie 2000(14) | 60F | Ethmoid sinus | Not provided | Died of colon carcinoma; persistent abnormal chemistry | Hemangiopericytoma | Insufficient data for analysis |

| Sandhu 2000(15) | 46M | Ethmoid sinus | HPC-like areas | ANED, normal chemistry | Hemangiopericytoma | Hemangiopericytoma |

| John 2001 (16) | 54F | Maxillary sinus | Characteristics schwann cells nuclear palisading | ANED, normal chemistry | Hemangiopericytoma | Insufficient data for analysis |

| Folpe 2004 (2) | 46M | Ethmoid sinus | Bland spindled cells, thick-walled vasculature | Recurred 1 year after original surgery, reexcised; ANED 12 years, normal chemistry | Hemangiopericytoma | Probable variant of sinonasal hemangiopericytoma-like tumor |

| Folpe 2004 (2) | 21M | Ethmoid sinus/sphenoid sinuses | Bland spindled cells, thick-walled vasculature | ANED 2 years, normal chemistry | Perivascular myxoid tumor | Probable variant of sinonasal hemangiopericytoma-like tumor |

Phosphaturic mesenchymal tumor (PMT) is an uncommon, distinctive tumor that is frequently associated with oncogenic osteomalacia, itself a rare paraneoplastic syndrome. Sinonasal PMT is the rarest variant with its own peculiar histologic features, often differs from the mixed connective tissue type, and more closely resembles a sinonasal hemangiopericytoma-like variant (1). PMT is usually a benign tumor, but some cases of malignant transformation have been described (7). Metastatic disease has also been reported (malignant connective tissue variant) (7). Osteogenic osteomalacia – the clinical effect of the tumor – is vitamin D resistant, and is dramatically cured by tumor removal.

PMT is usually located in soft tissue, but intraosseous as well as sinonasal locations have also been reported. In Folpe et al.’s own series of PMT, 18 out of 32 total cases occurred in soft tissue, nine in bone and two in paranasal sinuses, including the present one (2). Patients are usually in their adulthood at the time of diagnosis, but pediatric cases have also been reported (age range: 5 to 63 years). Any site can be affected, with the lower extremities being the most common (40–50% of cases), followed by the head and neck area (15–20%), trunk (15–20%) and upper extremities (around 10%). Unusual locations (e.g. big toe) are not uncommon. Tumor size is variable, ranging from 1 cm to 15 cm, with a median size of 5.6 cm for soft tissue location (3, 4). Somatostatin receptor imaging has been recently proved to improve the detection of such tumors, based on the postulate that such tumors express somatostatin receptors (5).

In conclusion, PMT is a rare pathologic entity that is poorly understood by pathologists, clinicians and radiologists. PMT of craniofacial sinuses has peculiar histological features, which often differs from the mixed connective tissue type and which more closely resembles a sinonasal hemangiopericytoma-like tumor variant. Craniofacial PMT should be considered as a rare causative tumor in patients presenting with clinical and radiological features of oncogenic osteomalacia.

Acknowledgements

The Authors have disclosed any financial or conflict of interests.

References

- 1.Thompson LDR, Miettinen M, Wenig BM. Sinonasal-type hemangiopericytoma. A clinicopathologic and immunophenotypic analysis of 104 cases showing perivascular myoid differentiation. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27:737–749. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200306000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Folpe AL, Fanburg-Smith JC, Billings SD, Bisceglia M, Bertoni F, Cho JY, Econs MJ, Inwards CY, Jan de Beur SM, Mentzel T, Montgomery E, Michal M, Miettinen M, Mills SE, Reith JD, O'Connell JX, Rosenberg AE, Rubin BP, Sweet DE, Vinh TN, Wold LE, Wehrli BM, White KE, Zaino RJ, Weiss SW. Most osteomalacia-associated mesenchymal tumors are a single histopathological entity. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28:1–30. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200401000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weiss D, Bar RS, Weidner N, Wener M, Lee F. Oncogenic osteomalacia: strange tumors in strange places. Postgrad Med J. 1985;61:349–355. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.61.714.349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sundaram M, McCarthy EF. Oncogenic osteomalacia. Skeletal Radiol. 2000;29:117–124. doi: 10.1007/s002560050581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Beur SM, Finnegan RB, Vassiliadis J, Cook B, Barberio D, Estes S, Manavalan P, Petroziello J, Madden SL, Cho JY, Kumar R, Levine MA, Schiavi SC. Tumors associated with oncogenic osteomalacia express genes important in bone and mineral metabolism. J Bone Miner Res. 2002;17:1102–1110. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2002.17.6.1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shimada T, Mizutani S, Muto T, Yoneya T, Hino R, Takeda S, Takeuchi Y, Fujita T, Fukumoto S, Yamashita T. Cloning and characterization of FGF23 as a causative factor of tumor-induced osteomalacia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:6500–6505. doi: 10.1073/pnas.101545198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bisceglia M, Spagnolo D, Galliani C, Fisher C, Suster S, Kazakov DV, Cooper K, Michal M. Tumoral, quasitumoral and pseudotumoral lesions of the superficial and somatic soft tissue: new entities and new variants of old entities recorded during the last 25 years. Part V: Excerpta III. Pathol. 2004;96:481–495. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Linsey M, Smith W, Yamauchi H, Bernstein L. Nasopharyngeal angiofibroma presenting as adult osteomalacia: case report and review of the literature. Laryngoscope. 1983;102:869–870. doi: 10.1002/lary.1983.93.10.1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weidner N, Santa Cruz D. Phosphaturic mesenchymal tumors: a polymorphous group causing osteomalacia or rickets. Cancer. 1987;59:1442–1454. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19870415)59:8<1442::aid-cncr2820590810>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Papotti M, Foschini MP, Isaia G, Rizzi G, Betts CM, Eusebi V. Hypophosphatemic oncogenic osteomalacia: report of three new cases. Tumori. 1988;74:599–607. doi: 10.1177/030089168807400519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wilkins GE, Granleese S, Hegele RG, Holden J, Anderson DW, Bondy GP. Oncogenic osteomalacia: evidence for a humoral phosphaturic factor. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1995;80:1628–1634. doi: 10.1210/jcem.80.5.7745010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gonzalez-Compta X, Mañós-Pujol M, Foglia-Fernandez M, Peral E, Condom E, Claveguera T, Dicenta-Sousa M. Oncogenic osteomalacia: case report and review of head and neck associated tumours. J Laryngol Otol. 1998;112:389–392. doi: 10.1017/s0022215100140551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ohashi K, Ohnishi T, Ishikawa T, Tani H, Uesugi K, Takagi M. Oncogenic osteomalacia presenting as bilateral stress fracture of the tibia. Skeletal Radiol. 1999;28:46–48. doi: 10.1007/s002560050471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clunie GP, Fox PE, Stamp TC. Four cases of acquired hypophosphatemic (‘oncogenic’) osteomalacia: problems of diagnosis, treatment and long-term management. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2000;39:1415–1421. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/39.12.1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sandhu FA, Martuza RL. Craniofacial hemangiopericytoma associated with oncogenic osteomalacia: case report. J Neurooncol. 2000;46:241–247. doi: 10.1023/a:1006352106762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.John MR, Wickert H, Zaar K, Jonsson KB, Grauer A, Ruppersberger P, Schmidt-Gayk H, Murer H, Ziegler R, Blind E. A case of neuroendocrine oncogenic osteomalacia associated with a PHEX and fibroblast growth factor-23 expressing sinusoidal malignant schwannoma. Bone. 2001;29:393–402. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(01)00586-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]