Summary

The rapid onset of the Domino Effect following the first Vertebral Compression Fracture is a direct consequence of the mechanical variations that affect the spine when physiological curves are modified. The degree of kyphosis influences the intensity of the Flexor Moment; this is greater on vertebrae D7, D8 and on vertebrae D12, L1 when the spine flexes. Fractures of D7, D8, D12 and L1 are, by far, the most frequent and also the main cause of the mechanical alterations that can trigger the Domino Effect. For these considerations vertebrae D7, D8, D12 and L1 have to be taken in consideration as “critical". In the case of critical clinical vertebral fractures it is useful to provide an indication for minimally invasive surgical reduction or intrasomatic stabilization. When occurs a fracture of a “critical vertebra”, prompt restoration of the heights leads to a reduction in the Kyphosis Index and therefore in the Flexor Moment, not only of the fractured vertebra but also, in turn, of all the other metameres which, even if morphologically still intact, are structurally fragile; so, through the restoration of the mechanical vertebral proprieties, we can reduce the risk of the Domino Effect. At the same time the prompt implementation of osteoinductive therapy is indispensable in order to achieve rapid and intense reconstruction of the trabecular bone, the strength of which increases significantly in a short period of time. Clinical studies are necessary to confirm the reduction of the domino effect following a fragility fracture of "critical vertebrae" with the restoration of the mechanical properties together with anabolic therapy.

Keywords: Vertebral Compression Fracture (VCF), Vertebral Compression Fractures (VCFs), Domino Effect (DE), Flexor Moment (FM), Kyphosis Index (KI), Vertebral Deformity Degree (VDD), Vertebral Deformity Exacerbation Rate (VDER), Vertebral Deformity Gain (VDG), Polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA)

Introduction

The structural peculiarities of spongy bone enable the vertebral bodies to be deformed without breaking, thereby withstanding the dynamic stresses caused by compression force. The thinning and the interruption of the trabeculae which occurs in fragile skeletal diseases reduce the strength of the vertebral body, which loses its load-bearing capacity.

Observational studies have shown that after the first Vertebral Compression Fracture (VCF), the risk of incurring further VCFs increases by 20% in the following year (1), is independent of BMD (Bone Mineral Density) (2), increases in proportion to the number and seriousness of the VCFs at the baseline (3,4) and, finally, is greater if the anterior height of the vertebra is reduced (5).

In osteoporotic women, dorsal hyperkyphosis is associated with a higher incidence of vertebral fractures (6). In dorsal hyperkyphosis caused by VCFs, the risk of femoral neck fractures also increases owing to unstable balance caused by the forward shift of the center of gravity to a position outside of the load-bearing base. This imbalance is associated with an elevated incidence of falling, especially in the elderly, which explains the increase in femoral neck fractures (7).

Mechanical pathogenesis of Domino Effect

The rapid onset of the Domino Effect (DE) following the first VCF (Figure 1) is a direct consequence of the mechanical variations that affect the spine when physiological curves are modified. The pathogenic moments which explain the DE from a mechanical point of view are:

Figure 1.

Domino Effect

VCFs in rapid progression revealed by the presence of MRI signal alteration, firstly in D12 and subsequently in L1 and L2.

the accentuation of dorsal kyphosis and inversion of lumbar lordosis;

the forward shift of the center of gravity (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Mechanical pathogenesis of Domino Effect

Dorsal hyperkyphosis caused by VCFs and forward shift of the center of gravity GA = gravitational axis; S = extent of shift of the center of gravity.

In orthostatism, the main stresses exerted on the spine are the compression force, which is uniform over the entire section of the vertebrae, and the flexion force, which varies according to the flexor moment.

The Flexor Moment (FM) is the product of the weight force (constant) multiplied by the length of the arm (variable); the length of the arm is the distance in a straight line drawn perpendicular to the gravitational axis and depends on the degree of kyphosis, which can be expressed by means of the Kyphosis Index (KI) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Kyphosis Index

KI = BD/AC

A = anterior superior margin T4; B = point of maximum convexity; C = anterior inferior margin T12.

Consequently, the degree of kyphosis influences the intensity of the FM (Figure 4); this is greater on vertebrae D7 and D8, which become physiologically more exposed to the risk of fracture (8).

Figure 4.

Flexor moment

FM = Wf x b

Wf = weight force (constant); b = arm (variable).

In addition to the vertebrae of the medial dorsal tract (D7-D8), the vertebrae which most frequently suffer fractures are those of the dorso-lumbar tract (D12-L1) (9) as a greater FM is exerted on these when the spine flexes (8).

Fractures of D7, D8, D12 and L1, which are by far the most frequent, are also the main cause of the mechanical alterations that can trigger the DE; they should therefore be considered in a totally different way from other fractures, i.e. as fractures of “critical vertebrae”, since the initial vertebral deformity is likely to worsen rapidly and the DE may ensue as a result of the increased flexor moment on all the other metameres (8).

In the case of critical clinical vertebral fractures, it is particularly useful to repeat radiography 15–20 days after the fracture, as comparison can reveal the evolution of the fracture, qualify any aggravation (Figure 5) and provide an indication for minimally invasive surgical reduction or intrasomatic stabilization.

Figure 5.

Rapid aggravation of deformities in “critical” VCFs

D8 deformity from slight to severe in 15 days following L1 fracture and D12 deformity from slight to severe in 20 days.

The Vertebral Deformity Degree (VDD) can be calculated and expressed as a percentage by means of the formula:

where

d % = percentage degree of deformity

hp = posterior height

ha(m) = anterior or medial height

The Vertebral Deformity Exacerbation Rate (VDER) can be calculated by means of the formula:

where

a = percentage aggravation

d%T0 = degree of initial deformity reported at time T0 (baseline)

d%T1 = degree of final deformity reported at time T1 (after 15–20 days)

In the case of a fracture of a “critical vertebra”, prompt restoration of the heights leads to a reduction in the KI and therefore in the FM, not only of the fractured vertebra but also, in turn of all the other metameres, which, though morphologically still intact, are structurally fragile; this reduces the risk of the DE (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Restoring heights in D8 reduces the Kyphosis Index and the Flexor Moment at time T1.

Restoring the heights reduces the length of the arm (Y-Z), thereby reducing the FM at time T1 not only on D8 [FM(D8) = X•(Y-Z)] but also on the other metameres [FM(D7,D9) = X• (Y-Z1); FM(D6,D10) = X• (Y-Z2)]; consequently, the risk of DE diminishes. Obviously, restoring vertebral heights in the case of a VCF of a critical vertebra cannot eliminate the risk of DE, but it can surely reduce it; indeed, the systemic bone fragility that led to the first VCF remains.

In the presence of skeletal fragility, it is useful to be able to evaluate in advance the effects of the mechanical imbalance induced by VCFs; this implies recognizing the critical nature of the fracture and identifying those vertebrae that are most vulnerable to mechanical stress. In critical VCFs, appropriate intervention to restore the heights and reinforce the structure of the vertebra, which is now possible through suitable pharmacological therapy, would avoid, or at least reduce, the risk of DE.

Moderate-severe deformities of “critical vertebrae” exert a mechanically unfavorable effect on the whole dorso-lumbar spine by increasing the flexion stress on all the vertebrae. Consequently, in the case of an acute fracture of a “critical vertebra” (D7, D8, D12 and L1), in which the FM is greater and the VDER is particularly high, restoring vertebral heights by means of minimally invasive intrasomatic reduction-stabilization (kyphoplasty) can prevent the consequences of mechanical decompensation which lead to the DE.

The degree of correction of the vertebral deformity is expressed in terms of the Vertebral Deformity Gain (VDG); this is a percentage value indicating the degree of correction in relation to the initial degree of the deformity, and depends on the extent to which the vertebral heights can be restored. Clearly, intrasomatic reduction-stabilization must be carried out promptly in order to obtain the best possible result in terms of VDG (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

VDG = Vertebral Deformity Gain

Percentage value indicating the degree of correction in relation to the initial degree of the deformity.

Two minimally invasive surgical methods currently enable vertebral fractures due to fragility to be treated in accordance with the above-mentioned criteria: vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty. Both involve injecting low-viscosity acrylic cement (PMMA polymethylmethacrylate) into the vertebral body.

Unlike vertebroplasty, kyphoplasty can reduce deformity in recent fractures of “critical vertebrae” by inserting a balloon inside the vertebral body: the balloon is then inflated until the morphology of the vertebral body is restored as far as possible. Subsequently, cement is injected at low pressure in order to stabilize the vertebra.

Regardless of which technique the operator decides to adopt, we propose the following criteria for use in the minimally invasive treatment of a VCF:

intrasomatic stabilization in the early treatment of critical VCFs without deformity and in the late treatment of non-critical VCFs;

reduction and intrasomatic stabilization in the early treatment of critical VCFs with deformity in rapid progression (Figure 8).

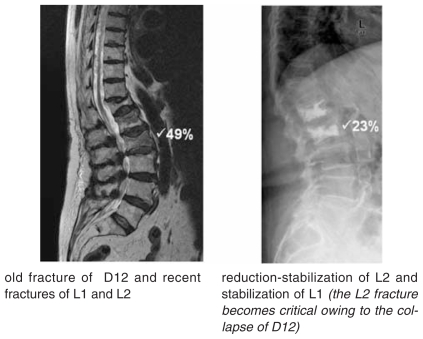

Figure 8.

Minimally invasive intrasomatic reduction-stabilization.

old fracture of D12 and recent fractures of L1 and L2

reduction-stabilization of L2 and stabilization of L1 (the L2 fracture becomes critical owing to the collapse of D12)

The loss of flexibility after intrasomatic cementation of a VCF is caused not only by the collapse and thickening of the trabecular structures, but also, and especially, by the injection of PMMA into the vertebral body.

On account of its physical proprieties, PMMA acts as an amplifier of stress, thereby increasing the risk of fracture of adjacent vertebrae (10–13). The use of so-called “osteoconductor” materials, such as calcium carbonate and calcium triphosphate, is therefore justified, as these tend to reproduce the bone structure.

VCFs are the most evident clinical manifestation of the seriousness of systemic osteopathy due to fragility; correct diagnosis and adequate pharmacological treatment are therefore essential.

Whenever intrasomatic reduction or stabilization of VCFs is undertaken, the prompt implementation of osteoinductive therapy must be considered; indeed, this is indispensable in order to achieve rapid and intense reconstruction of the trabecular bone, the strength of which increases significantly in a short time.

In vivo analysis of finished elements has demonstrated that 24-month administration of theriparatide, which is efficacious in increasing the thickness and connectivity of the trabeculae, increases the resistance of the vertebral body to compression and torsion by 30% (14). Moreover, the administration of strontium ranelate has yielded encouraging results in terms of increased vertebral resistance to compression in an animal model (15) and appears to prevent the progression of kyphosis in women with VCFs (16,17).

Conclusions

On the basis of the above considerations, we can conclude that:

maintaining the physiological curves of the spine is a prerequisite to limiting the progression of VCFs;

reducing the FM by restoring vertebral heights (VDG) in “critical vertebrae” (D7, D8, D12, L1) helps to reduce the risk of additional fractures (DE);

these key points (a and b) can be achieved through minimally invasive intrasomatic reduction-stabilization (vertebro-kyphoplasty), which, in some cases, may require intersomatic stabilization in open surgery.

the intrasomatic reduction-stabilization of VCFs must always be associated to pharmacological treatment with osteoinductors, which stimulate bone formation and increase strength;

in intrasomatic stabilization procedures the use of osteoconductors to promote bone integration is to be recommended, especially in patients with a long life expectancy.

Comment

Application of the above-mentioned biomechanical concepts in daily clinical practice, although still limited to a statistically non-significant number of patients with severe osteoporosis and ≥ 30% deformity of “critical vertebrae”, the early use of minimally invasive intrasomatic reduction-stabilization and pharmacological treatment with osteoconductors have yielded encouraging results. Indeed, the DE has not manifested itself in two years of observation.

However, prospective studies based on biomechanical analysis and on the surgical-pharmacological approach will need to be conducted on a greater number of cases. These should confirm the efficacy of promptly restoring the heights of fractured critical vertebrae and of increasing bone strength through pharmacological treatment in order to limit the devastating consequences of the DE.

Arresting the progression of VCFs means improving both the quality of life and life expectancy of patients, and is undoubtedly advantageous from the cost-benefit ratio point of view.

References

- 1.Lindsay R, Silverman SL, Cooper C, Hanley DA, Barton I, Broy SB, Licata A, Benhamou L, Geusens P, Flowers K, Stracke H, See-man E. Risk of new vertebral fracture in the year following a fracture. JAMA. 2001 Jan 17;285(3):320–3. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.3.320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reginster J, Minne HW, Sorensen OH, Hooper M, Roux C, Brandi ML, Lund B, Ethgen D, Pack S, Roumagnac I, Eastell R. Randomized trial of the effects of risedronate on vertebral fractures in women with established postmenopausal osteoporosis. Vertebral Efficacy with Risedronate therapy (VERT) Study Group. Osteoporos Int. 2000;11(1):83–91. doi: 10.1007/s001980050010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Delmas PD, Genant HK, Crans GG, Stock JL, Wong M, Siris E, Adachi JD. Severity of prevalent vertebral fractures and the risk of subsequent vertebral and nonvertebral fractures: results from the MORE trial. Bone. 2003 Oct;33(4:):522–32. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(03)00241-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gallagher, et al. FIT Study. Calcif Tissue Int. 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lunt M, O'Neill TW, Felsenberg D, Reeve J, Kanis JA, Cooper C, Silman AJ European Prospective Osteoporosis Study Group. Characteristics of a prevalent vertebral deformity predict subsequent vertebral fracture: results from the European Prospective Osteoporosis Study (EPOS) Bone. 2003 Oct;33(4):505–13. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(03)00248-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roux C, Fechtenbaum J, Kolta S, Said-Nahal R, Briot K, Benhamou CL. Prospective assessment of thoracic kyphosis in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Res. 2010 Feb;25(2):362–8. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.090727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johell O, Kanis J, Black DM, Belogh A, Poor G, Sarkar S, Zhou C, Pavo I. Association Between Risk Factors and Vertebral Fracture Risk in the Multiple Outcomes of Raloxifene Evaluation (More) JBMR. 2004;19:764–772. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.040211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nardi A, Ventura L, Rossini M, Ramazzina E. The importance of mechanics in the pathogenesis of fragility fractures of the femur and vertebrae. Clinical Cases in Mineral and Bone Metabolism. 2010;7(2):130–134. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cooper C, Atkinson EJ, O'Fallon WM, Melton LJ. Incidence of clinically diagnosed vertebral fractures: a population-based study in Rochester, Minnesota, 1985–1989. J Bone Min Res. 1992;7:221–227. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650070214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Trout AT, Kallmes DF, Lane JI, Layton KF, Marx WF. Subsequent vertebral fractures after vertebroplasty: association with intraosseous clefts. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2006 Aug;27(7):1586–91. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Trout AT, Kallmes DF, Kaufmann TJ. New fractures after vertebroplasty: adjacent fractures occur significantly sooner. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2006 Jan;27(1):217–23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Trout AT, Kallmes DF. Does vertebroplasty cause incident vertebral fractures? A review of available data. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2006 Aug;27(7:):1397–403. Review. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mudano AS, Bian J, Cope JU, Curtis JR, Gross TP, Allison JJ, Kim Y, Briggs D, Melton ME, Xi J, Saag KG. Vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty are associated with an increased risk of secondary vertebral compression fractures: a population-based cohort study. Osteoporos Int. 2009 May;20(5:):819–26. doi: 10.1007/s00198-008-0745-5. Epub 2008 Sep 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Graeff C, Chevalier Y, Charlebois M, Varga P, Pahr D, Nickelsen TN, Morlock MM, Glüer CC, Zysset PK. Improvements in vertebral body strength under teriparatide treatment assessed in vivo by finite element analysis: results from the EUROFORS study. J Bone Miner Res. 2009 Oct;24(10):1672–80. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.090416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ammann P, Shen V, Robin B, Mauras Y, Bonjour JP, Rizzoli R. Strontium ranelate improves bone resistance by increasing bone mass and improving architecture in intact female rats. J Bone Miner Res. 2004 Dec;19(12:):2012–20. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.040906. Epub 2004 Sep 13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roux C, Fechtenbaum J, Kolta S, Isaia G, Andia JB, Devogelaer JP. Strontium ranelate reduces the risk of vertebral fracture in young postmenopausal women with severe osteoporosis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008 Dec;67(12:):1736–8. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.094516. Epub 2008 Aug 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roux C, Fechtenbaum J, Briot K, Cropet C, Liu-Léage S, Marcelli C. Inverse relationship between vertebral fractures and spine osteoarthritis in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. Ann. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.069369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]