Abstract

BACKGROUND

Over the past 10 years, there has been a significant increase in the use of assisted reproductive technologies in Canada, however, little is known about the overall prevalence of infertility in the population. The purpose of the present study was to estimate the prevalence of current infertility in Canada according to three definitions of the risk of conception.

METHODS

Data from the infertility component of the 2009–2010 Canadian Community Health Survey were analyzed for married and common-law couples with a female partner aged 18–44. The three definitions of the risk of conception were derived sequentially starting with birth control use in the previous 12 months, adding reported sexual intercourse in the previous 12 months, then pregnancy intent. Prevalence and odds ratios of current infertility were estimated by selected characteristics.

RESULTS

Estimates of the prevalence of current infertility ranged from 11.5% (95% CI 10.2, 12.9) to 15.7% (95% CI 14.2, 17.4). Each estimate represented an increase in current infertility prevalence in Canada when compared with previous national estimates. Couples with lower parity (0 or 1 child) had significantly higher odds of experiencing current infertility when the female partner was aged 35–44 years versus 18–34 years. Lower odds of experiencing current infertility were observed for multiparous couples regardless of age group of the female partner, when compared with nulliparous couples.

CONCLUSIONS

The present study suggests that the prevalence of current infertility has increased since the last time it was measured in Canada, and is associated with the age of the female partner and parity.

Keywords: prevalence, infertility, epidemiology, risk factors

Introduction

Infertility has important implications for individual and public health in Canada. The emotional, physical and financial costs borne by couples experiencing infertility can be substantial (Goldman et al., 2000; Chambers et al., 2009; Macaluso et al., 2010), while the health care system bears the cost of preterm or multiple births that can result from infertility treatments (Allen et al., 2006; Bouzayen and Eggertson, 2009; Deonandan, 2010).

Although infertility is estimated to affect 10–15% of couples in industrialized countries (Evers, 2002), how infertility is defined and measured can result in wide-ranging estimates of prevalence (Marchbanks et al., 1989; Thonneau and Spira, 1990; Guzick and Swan, 2006; Gurunath et al., 2011). Epidemiological studies tend to categorize women as infertile if they have attempted to become pregnant without success while being exposed to the risk of conception (Gurunath et al., 2011), however the definition of the risk of conception can vary. In some studies, risk of conception refers to lack of contraception use (Dulberg and Stephens, 1993; Bhattacharya et al., 2009) while in others it refers to regular, unprotected sexual intercourse (Webb and Holman, 1992). The duration of exposure to risk is often 12 months (Sciarra, 1994), but can be longer (Rowe et al., 1993). Studies have also differentiated between ‘current’ infertility (i.e. are you now having difficulty conceiving?) versus ‘lifetime’ infertility (i.e. have you ever had difficulty conceiving?). Current infertility is generally less prevalent than lifetime infertility, as the latter sums up all infertility experiences in a woman's life (Boivin et al., 2007, 2009). Despite definitional differences, many studies have found the prevalence of infertility to be associated with the female partner's age, parity and marital status (Chandra and Stephen, 1998; Herbert et al., 2009) as well as lifestyle factors such as smoking and BMI (Grodstein et al., 1994; Kelly-Weeder and Cox, 2006; Brassard et al., 2008).

In Canada, national estimates of the prevalence of infertility have been published infrequently. Researchers using the 1984 Canadian Fertility Survey categorized women as infertile if they did not become pregnant while not using contraception. They estimated the prevalence of infertility to be 5.4% among women aged 18–44 who were married or living common-law and whose duration of exposure to risk was the previous 12 months (Balakrishnan and Fernando, 1993). Eight years later, researchers using data from the 1992 surveys sponsored by The Royal Commission on New Reproductive Technologies categorized women as infertile if they reported no contraception use and no pregnancy during the 12 months prior to the interview. Under this definition, 8.5% of women 18–44 years of age who were married or living common-law were considered infertile (Dulberg and Stephens, 1993).

Over the past 10 years, there has been a significant increase in the use of assisted reproductive technologies in Canada (Gunby et al., 2005, 2009, 2010, 2011), however, little is known about the overall prevalence of infertility in the population. Using data from the Infertility component in the 2009–2010 Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS), the purpose of the present study was to estimate the prevalence of current infertility in Canada, according to three definitions of the risk of conception. Further, this study examined associations between couples' socio-demographic characteristics and their risk of current infertility.

Materials and Methods

Data sources and study population

Data from the Infertility (IFT) component of the 2009–2010 CCHS conducted by Statistics Canada were used. The target population of the IFT component consisted of opposite-sex couples in the 10 provinces living in private dwellings where the female spouse was aged 18–49. The couple also had to be living together in the same household at the time of the survey. The target population excluded the three Territories, as well as persons living on Indian Reserves or Crown lands, those residing in institutions, full-time members of the Canadian Forces and residents of certain remote regions.

The CCHS used a multistage stratified cluster sampling strategy, described in detail elsewhere (Statistics Canada, 2011b). Data for the IFT component were collected from September to December 2009 and from July to August 2010. In total, 41 501 of the CCHS units selected during these collection periods were in-scope for the CCHS. Once contacted by telephone or in person, 33 468 households agreed to participate in the CCHS resulting in a CCHS household-level response rate of 80.6%. In each responding household, one person was selected to participate in the survey. In the end, CCHS responses were obtained for 29 858 individuals, resulting in a CCHS person-level response rate of 89.2%. Among these respondents, 6520 were eligible for the IFT component and 5617 completed it, for an IFT person-level response rate of 86.2%. Multiplying the CCHS household-level response rate, the CCHS person-level response rate and the IFT person-level response rate yields an estimated overall response rate for IFT of 62.0% (Statistics Canada, 2010a).

For inclusion in the present study, subjects were required to be married or living common-law for at least the 12 months prior to the date of interview, their use of birth control and their pregnancy status in the 12 months prior to the interview were reported, and the female partner was aged 18–44 years. Applying these criteria resulted in a sample of 4412 couples.

Study variables

Socio-demographic characteristics were examined including the age group in years of the female partner (18–24, 25–29, 30–34, 35–39 and 40–44), age group in years of the male partner (18–24, 25–29, 30–34, 35–39, 40–44 and 45 and older), the female partner's highest level of education (less than secondary school, secondary school graduation and post secondary degree or diploma), the couple's marital status (married or common-law) and their parity (zero, one, or two or more children). To examine the potential interaction between parity and age group of female partner, a composite measure was derived (0, 18–34; 0, 35–44; 1, 18–34; 1, 35–44; 2+, 18–34 and 2+, 35–44). Household income quartiles ($29 650 or less, >$29 650–$44 050, >$44 050–$64 450, more than $64 450) were derived based on a modified version of the equivalence score method, which adjusts household income by household size. This method was developed at Statistics Canada (Carson, 2002) and uses a weight factor based on the ‘40/30’ rule. For each respondent in the study population, a household weight factor was calculated based on the number of people in the household. The first household member was assigned a weight of 1; the second member, a weight of 0.4; and the third and all subsequent members, a weight of 0.3. The household weight factor was then calculated as the sum of these weights. For example, for a four-member household, it would be 2.0 (1 + 0.4 + 0.3 + 0.3). Household income was then divided by the household weight factor to derive the income adjusted for household size. The adjusted household incomes were then grouped into quartiles (four groups, each containing one-fourth of the study population).

Definitions

Use of birth control within the past 12 months

Respondents were categorized as having used birth control if they responded yes to the question ‘Within the past 12 months, did you or your partner use any form of birth control?’ Respondents were also categorized as having used birth control if they answered no to the above question, but reported that their reason for not using birth control was ‘they or their partner have had a vasectomy, a hysterectomy or had their tubes tied’.

Pregnant in the past 12 months

Respondents were categorized as being pregnant if they responded yes to the question ‘Are you or your partner currently pregnant?’ or responded yes to the question ‘In the past 12 months did you or your partner become pregnant?’

Current infertility

For the purposes of this study, couples were categorized as currently infertile if they did not become pregnant after exposure to the risk of conception during the previous 12 months.

Risk of conception

Risk of conception was defined in three different ways: (i) did not use any form of birth control within the past 12 months (ii) did not use any form of birth control within the past 12 months and reported having sexual intercourse in the past 12 months (iii) did not use any form of birth control within the past 12 months, reported having sexual intercourse in the past 12 months, and reported ever having tried to become pregnant with their current partner. The first definition is consistent with what was applied in previous studies in Canada (Balakrishnan and Fernando, 1993; Dulberg and Stephens, 1993) and assumes that the couples had intercourse within the past 12 months. The second definition builds on the first by explicitly including sexual intercourse within the past 12 months as a criterion. The third definition builds on the second by including an indicator of the couple's desire to become pregnant.

Prevalence of current infertility

The prevalence of current infertility was estimated by dividing the number of couples categorized as currently infertile by the number of couples in the target population.

Statistical analyses

Because current infertility status was an attribute of the couple, analyses were weighted using the couple-level survey weight rather than the person-level weight. Using the couple-level weight ensured that weighted estimates were representative of the number of couples in 2009–2010 rather than the number of individuals (Statistics Canada, 2010a).

The data were analyzed with SAS 9.1 and SUDAAN 10 software. Proportions and their confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated. A separate logistic regression model was run for each of the three definitions of current infertility to estimate the association between current infertility and the composite measure of parity and age group of the female partner, marital status, highest level of education of the female partner and household income. Variance estimation (95% CIs) and significance testing (t-test or Wald F-statistic) of differences between estimates were done using the replicate weights to account for the survey's complex sampling design. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05, but was Bonferroni-adjusted depending on the number of comparisons (Abdi, 2007).

Results

Characteristics of couples in Canada

In 2009–2010, about 3.2million couples were married or living common-law for at least 12 months with a female partner 18–44 years of age (Table I). Just over 50% of couples had a female partner between the ages of 35 and 44, while 63% of couples had a male partner aged 35 or over. Seventy-four percent of couples were married and 70% of couples had at least one child. Among the couples with no children, about one-third also had a female partner between the ages of 35 and 44. Seventy-four percent of couples had a female partner with a post secondary diploma or degree, and couples in the top income quartile had a household income greater than $64 450 in the previous 12 months.

Table I.

Characteristics of couples in Canada.

| 2009–2010 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample size | Weighted sample size | % | 95% CI |

||

| From | To | ||||

| All couples | 4412 | 3 225 900 | 100.0 | ||

| Age group of female partner | |||||

| 18–24 years | 356 | 247 000 | 7.7 | 7.2 | 8.1 |

| 25–29 years | 847 | 596 100 | 18.5 | 17.8 | 19.2 |

| 30–34 years | 1164 | 758 000 | 23.5 | 22.7 | 24.3 |

| 35–39 years | 1142 | 793 200 | 24.6 | 23.8 | 25.4 |

| 40–44 years | 903 | 831 600 | 25.8 | 24.3 | 27.4 |

| Age group of male partner | |||||

| 18–24 years | 171 | 109 300 | 3.4 | 2.8 | 4.1 |

| 25–29 years | 605 | 445 100 | 13.8 | 12.7 | 14.9 |

| 30–34 years | 995 | 647 000 | 20.1 | 18.8 | 21.4 |

| 35–39 years | 1140 | 741 500 | 23.0 | 21.7 | 24.3 |

| 40–44 years | 878 | 730 300 | 22.6 | 20.9 | 24.5 |

| 45 and older | 623 | 552 600 | 17.1 | 15.5 | 18.9 |

| Marital status | |||||

| Common-law | 1181 | 839 800 | 26.0 | 24.4 | 27.8 |

| Married | 3231 | 2 386 100 | 74.0 | 72.2 | 75.6 |

| Parity | |||||

| 0 children | 1320 | 972 200 | 30.1 | 28.3 | 32.0 |

| 1 child | 1029 | 693 700 | 21.5 | 19.8 | 23.4 |

| 2 or more children | 2063 | 1 560 000 | 48.4 | 46.2 | 50.5 |

| Parity, age group of female partner | |||||

| 0, 18–34 years | 848 | 660 500 | 20.5 | 19.1 | 22.0 |

| 0, 35–44 years | 472 | 311 700 | 9.7 | 8.5 | 10.9 |

| 1, 18–34 years | 613 | 393 400 | 12.2 | 11.0 | 13.5 |

| 1, 35–44 years | 416 | 300 300 | 9.3 | 8.1 | 10.6 |

| 2+, 18–34 years | 906 | 547 100 | 17.0 | 15.7 | 18.3 |

| 2+, 35–44 years | 1157 | 1 012 900 | 31.4 | 29.6 | 33.3 |

| Highest level of education of female partner | |||||

| Less than secondary school graduation | 229 | 153 400 | 4.8 | 4.0 | 5.8 |

| Secondary school graduation | 881 | 666 700 | 21.0 | 19.2 | 22.9 |

| Post secondary degree or diploma | 3241 | 2 358 800 | 74.2 | 72.2 | 76.1 |

| Used birth control within the previous 12 months | |||||

| Yes | 3343 | 2 437 500 | 75.6 | 73.7 | 77.4 |

| No | 1069 | 788 400 | 24.4 | 22.6 | 26.3 |

| Pregnant within the previous 12 months | |||||

| Yes | 770 | 525 000 | 16.3 | 14.9 | 17.7 |

| No | 3642 | 2 700 900 | 83.7 | 82.3 | 85.1 |

| Had sexual intercourse within the previous 12 months | |||||

| Yes | 4129 | 2 966 300 | 98.9 | 98.3 | 99.3 |

| No | 36 | 33 000 | 1.1 | 0.7 | 1.7 |

| Ever tried to become pregnant with current partner | |||||

| Yes | 3523 | 2 533 700 | 78.6 | 76.9 | 80.3 |

| No | 886 | 688 100 | 21.4 | 19.7 | 23.1 |

CI, confidence interval.

Weighted sample sizes have been rounded to the nearest 100.

Notes: Includes couples who lived together for at least the previous 12 months, the female partner was 18–44 years old, and the couples' use of birth control and pregnancy status within the past 12 months was known. Source: 2009–2010 CCHS.

Examining the individual criteria used to define current infertility indicated that within the previous 12 months 99% of couples reported having sexual intercourse, 76% of couples reported using some form of birth control and 16% of couples reported being pregnant. Furthermore, about 79% of couples reported ever having tried to become pregnant with their current partner.

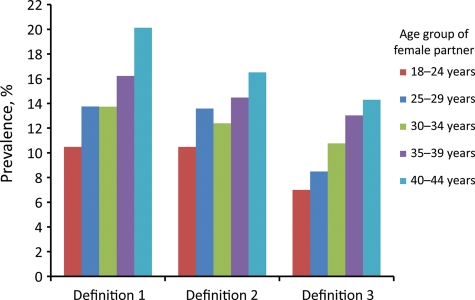

Prevalence of current infertility

According to Definition 1, about 16% of couples experienced current infertility in 2009–2010 (Table II). This was higher than the prevalence of 14% produced by Definition 2 and the prevalence of 11.5% produced by Definition 3. Prevalence varied mainly by age group of the female partner and parity (Table III). The linear age trend in prevalence according to Definitions 1 and 3 was statistically significant (Fig. 1). A similar age trend was not evident for age group of the male partner.

Table II.

Prevalence of current infertility according to three definitions.

| Total number (weighted) of couples currently infertile | Total number (weighted) of couples in target population | Prevalence (%) | 95% CI |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| From | To | ||||

| Definition 1 | 508 100 | 3 225 900 | 15.7 | 14.2 | 17.4 |

| Definition 2 | 445 500 | 3 176 900 | 14.0 | 12.6 | 15.6 |

| Definition 3 | 365 100 | 3 176 600 | 11.5 | 10.2 | 12.9 |

CI, confidence interval.

Weighted counts have been rounded to the nearest 100.

Notes: The number of couples in the target population for each definition differs slightly due to item non-response.

For Definition 2, if ‘had sexual intercourse in the past 12 months’ was not reported then the respondent was excluded from the target population. For Definition 3, if ‘had sexual intercourse in the past 12 months’ or ever tried to become pregnant with current partner' was not reported, then the respondent was excluded from the target population.

Definition 1: couples who reported no pregnancy and did not use any form of birth control during the previous 12 months.

Definition 2: couples who reported no pregnancy, did not use any form of birth control, and reported having sexual intercourse during the previous 12 months.

Definition 3: couples who reported no pregnancy, did not use any form of birth control, reported having sexual intercourse during the previous 12 months and had tried at some point to become pregnant with their current partner.

Source: 2009–2010 CCHS.

Table III.

Prevalence of current infertility according to three definitions, by selected characteristics.

| 2009–2010 |

2009–2010 |

2009–2010 |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Definition 1 (%) | 95% CI |

Definition 2 (%) | 95% CI |

Definition 3 (%) | 95% CI |

||||

| From | To | From | To | From | To | ||||

| Age group of female partnera | |||||||||

| 18 to 24 years | 10.5b | 6.2 | 17.2 | 10.5b | 6.2 | 17.2 | 7.0b | 3.6 | 13.2 |

| 25–29 years | 13.7 | 10.9 | 17.2 | 13.6 | 10.8 | 17.0 | 8.5 | 6.3 | 11.4 |

| 30–34 years | 13.7 | 11.2 | 16.8 | 12.4 | 9.9 | 15.4 | 10.8 | 8.5 | 13.5 |

| 35–39 years | 16.2 | 13.6 | 19.2 | 14.5 | 12.0 | 17.4 | 13.0 | 10.6 | 15.9 |

| 40–44 years | 20.1 | 16.2 | 24.7 | 16.5 | 13.1 | 20.6 | 14.3 | 11.2 | 18.1 |

| Age group of male partner | |||||||||

| 18–24 years | <20.9 | <20.9 | <16.2 | ||||||

| 25–29 yearsc | 12.2 | 8.9 | 16.5 | 11.8 | 8.5 | 16.1 | 7.2b | 4.9 | 10.4 |

| 30–34 years | 15.9 | 12.8 | 19.7 | 14.8 | 11.8 | 18.5 | 11.7 | 9.0 | 15.1 |

| 35–39 years | 13.6 | 11.2 | 16.6 | 12.6 | 10.2 | 15.4 | 11.4 | 9.2 | 14.1 |

| 40–44 years | 15.8 | 12.6 | 19.7 | 14.4 | 11.3 | 18.0 | 12.6 | 9.7 | 16.1 |

| 45 and older | 22.0* | 17.2 | 27.7 | 17.1 | 12.9 | 22.3 | 14.5* | 10.6 | 19.4 |

| Marital status | |||||||||

| Common-law | 13.5 | 11.0 | 16.4 | 12.2 | 9.8 | 15.1 | 7.8* | 6.0 | 10.2 |

| Marriedc | 16.6 | 14.7 | 18.7 | 14.7 | 12.9 | 16.6 | 12.8 | 11.2 | 14.6 |

| Parity | |||||||||

| 0 children | 20.6* | 17.8 | 23.7 | 18.7* | 15.9 | 21.7 | 10.2 | 8.3 | 12.5 |

| 1 child | 18.6* | 15.5 | 22.1 | 16.4* | 13.7 | 19.6 | 16.4* | 13.7 | 19.6 |

| 2 or more childrenc | 11.4 | 9.5 | 13.8 | 10.1 | 8.3 | 12.3 | 10.1 | 8.3 | 12.3 |

| Parity, age group of female partner | |||||||||

| 0, 18–34 years | 16.9 | 13.6 | 20.8 | 16.0 | 12.8 | 19.8 | 8.2 | 5.9 | 11.1 |

| 0, 35–44 years | 28.5*,d | 23.4 | 34.3 | 24.5*,d | 19.5 | 30.3 | 14.7d | 10.9 | 19.6 |

| 1, 18–34 years | 12.4 | 9.6 | 15.9 | 12.3 | 9.5 | 15.8 | 12.3 | 9.5 | 15.8 |

| 1, 35–44 years | 26.7*,d | 21.0 | 33.2 | 22.0*,d | 17.0 | 28.0 | 22.0*,d | 17.0 | 28.0 |

| 2+, 18–34 years | 9.4 | 6.8 | 12.9 | 8.6b | 6.1 | 12.0 | 8.6b | 6.1 | 12.0 |

| 2+, 35–44 yearsc | 12.6 | 9.9 | 15.8 | 10.9 | 8.5 | 14.0 | 10.9 | 8.5 | 14.0 |

| Highest level of education of female partner | |||||||||

| Less than secondary school graduation | 19.9b | 13.2 | 29.0 | 17.3b | 10.8 | 26.4 | 15.1b | 9.0 | 24.2 |

| Secondary school graduation | 15.9 | 12.5 | 20.1 | 14.2 | 11.0 | 18.1 | 11.3 | 8.4 | 15.1 |

| Post secondary degree or diplomac | 15.2 | 13.5 | 17.1 | 13.7 | 12.0 | 15.5 | 11.3 | 9.9 | 12.8 |

| Household income adjusted for household sizee | |||||||||

| First quartile ($29 650 or less) | 16.4 | 13.2 | 20.3 | 15.1 | 12.0 | 18.8 | 12.6 | 9.7 | 16.2 |

| Second quartile (>$29 650–$44 050) | 12.6 | 9.9 | 15.9 | 11.0 | 8.7 | 14.0 | 9.1 | 7.1 | 11.7 |

| Third quartile (>$44 050–$64 450) | 15.5 | 12.6 | 19.1 | 14.5 | 11.6 | 17.9 | 12.0 | 9.4 | 15.2 |

| Fourth quartile (more than $64 450)c | 16.6 | 13.8 | 19.9 | 15.7 | 12.8 | 19.0 | 12.2 | 9.8 | 15.1 |

If coefficient of variation of estimate exceeds 33.3%, estimate is indicated as being less than the upper limit of the 95% confidence interval.

Notes: Prevalence of current infertility was calculated by dividing the number of married or common-law couples categorized as infertile by the number of married or common-law couples who had lived together for at least the past 12 months.

Definition 1: couples who reported no pregnancy and did not use any form of birth control during the previous 12 months.

Definition 2: couples who reported no pregnancy, did not use any form of birth control, and reported having sexual intercourse during the previous 12 months.

Definition 3: couples who reported no pregnancy, did not use any form of birth control, reported having sexual intercourse during the previous 12 months and had tried at some point to become pregnant with their current partner.

Source: 2009–2010 CCHS.

CI, confidence interval.

*Significantly different from the reference category (P > 0.05 adjusted for number of comparisons).

aLinear age trend for Definition 1 and Definition 3 statistically significant (P < 0.01) but not statistically significant for Definition 2 (P > 0.05).

bData should be interpreted with caution because of high sampling variability (coefficient of variation ≥ 16.6% and <33.3%).

cReference category.

dWithin parity grouping, 35 to 44 years significantly different from 18 to 34 years (P < 0.05).

eAdjusted using 40/30 formula; adjusted household incomes for all respondents ranked and divided into quartiles.

Figure 1.

Prevalence of current infertility by age group of female partner, according to three definitions.

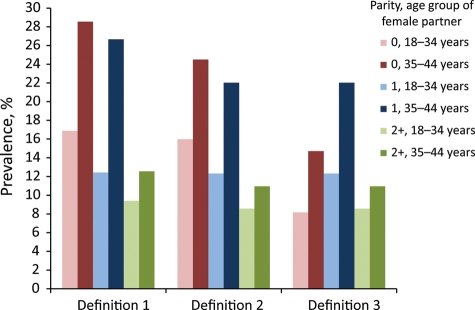

Regarding parity, couples with fewer than two children generally had a higher prevalence of current infertility than couples with two or more children, with one exception. According to Definition 3 only, couples with one child had a higher prevalence of infertility than couples with two or more children.

The prevalence of current infertility varied across the composite measure of parity and age group of the female partner. For couples with one or no children, the prevalence of current infertility was significantly higher when the female partner was 35–44 years of age compared with those of 18–34 years of age (Fig. 2). For couples with two or more children, prevalence did not differ across the age group of the female partner.

Figure 2.

Prevalence of current infertility by parity and age group of female partner, according to three definitions.

Only Definition 3 produced an association with marital status where a lower prevalence of current infertility was found among common-law couples (Table III). Highest level of education and household income were not associated with the prevalence of current infertility.

After controlling for highest level of education of the female partner and household income, both the composite measure of parity and age group of the female partner, and marital status were significantly associated with current infertility (Table IV). According to Definition 1, higher odds of experiencing current infertility were observed for couples with a female partner aged 35–44 years and no (OR 3.17, 95% CI 2.10–4.77) or one (OR 2.52, 95% CI 1.61–3.95) child compared with two or more children. Definitions 2 and 3 produced a similar result. Furthermore, Definitions 1 and 2 also yielded lower odds of current infertility for multiparous couples regardless of age group of the female partner, when compared with nulliparous couples. Lastly, Definitions 1 and 3 found that couples with lower parity (0 or 1 child) had significantly higher odds of experiencing current infertility when the female partner was aged 35–44 years versus 18–34 years. In all three models, couples who lived common-law had lower odds of experiencing current infertility than couples who were married.

Table IV.

Odds of experiencing current infertility according to three definitions.

| Definition 1, Odds ratio | 95% CI |

Definition 2, Odds ratio | 95% CI |

Definition 3, Odds ratio | 95% CI |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| From | To | From | To | From | To | ||||

| Parity, age group of female partner | |||||||||

| 0, 18–34 years | 1.78a,b | 1.18 | 2.68 | 1.90a,b | 1.25 | 2.88 | 0.89 | 0.54 | 1.48 |

| 0, 35–44 years | 3.17a,b,c | 2.10 | 4.77 | 2.76a,b | 1.79 | 4.24 | 1.63a,b,c | 1.01 | 2.64 |

| 1, 18–34 years | 1.16 | 0.76 | 1.76 | 1.28 | 0.84 | 1.95 | 1.32 | 0.86 | 2.02 |

| 1, 35–44 years | 2.52a,b,c | 1.61 | 3.95 | 2.35a,b,c | 1.48 | 3.74 | 2.37a,b,c | 1.49 | 3.77 |

| 2+, 18–34 years | 0.78 | 0.48 | 1.27 | 0.80 | 0.48 | 1.33 | 0.82 | 0.49 | 1.37 |

| 2+, 35–44 yearsd | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Marital status | |||||||||

| Common-law | 0.62a | 0.45 | 0.85 | 0.64a | 0.46 | 0.88 | 0.55a | 0.38 | 0.80 |

| Marriedd | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

CI, confidence interval.

Notes: Each model controlled for highest level of education of female partner and household income quartiles.

Definition 1: couples who reported no pregnancy and did not use any form of birth control during the previous 12 months.

Definition 2: couples who reported no pregnancy, did not use any form of birth control, and reported having sexual intercourse during the previous 12 months.

Definition 3: couples who reported no pregnancy, did not use any form of birth control, reported having sexual intercourse during the previous 12 months and had tried at some point to become pregnant with their current partner.

Source: 2009–2010 CCHS.

aSignificantly different from the reference category (P < 0.05).

bSignificantly different from 2+, 18–34 years (P < 0.05).

cWithin parity grouping, 35–44 years significantly different from 18 to 34 years (P < 0.05).

dReference category.

Discussion

Current infertility is defined as not achieving a pregnancy while being exposed to the risk of conception. In Canada, the prevalence of current infertility in 2009–2010 was between 11.5 and 15.7%, reflecting the use of three different definitions of the risk of conception. The highest prevalence of 15.7% resulted from defining the risk of conception as no birth control use in the previous 12 months. This definition was used the last time the prevalence of current infertility was measured in Canada, and a similar definition was used for the prevalence estimates produced by the Canadian Fertility Survey in 1984. Comparing the three sets of results suggests that according to this definition, the recent measure of overall prevalence is significantly higher than the prevalence of 5.4% in 1984 (Balakrishnan and Fernando, 1993) and 8.5% in 1992 (Dulberg and Stephens, 1993). Increases across age groups of the female partner were also observed. In 1984 the prevalence of current infertility among couples with a female partner between the ages of 40–44 was 4.6% (Balakrishnan and Fernando, 1993); an estimate that falls below the range of 14.3–20.7% observed for the same age group in 2009–2010. Similarly, the prevalence of 4.9% observed in 1984 for couples with a female partner aged 18–29 was also lower than the range of 7.0–13.7% found for the same age group in the present study.

The second definition of the risk of conception differed from the first by including sexual intercourse in the previous 12 months as a criterion, resulting in a prevalence of 14%. This criterion aligns Definition 2 more closely with what has been used in other studies of current infertility, but direct comparisons are difficult due to differences in age groups and marital status of the target populations, as well as variations in the questions and responses used to determine prevalence. Nonetheless, the prevalence of 14% falls within the range of 3.5–16.7% reported by population studies in other industrialized countries (Boivin et al., 2007, 2009).

The third definition of the risk of conception included the additional criterion of whether the couple had ever tried to become pregnant, resulting in a prevalence of 11.5%. Including a question about ‘trying for pregnancy’ when estimating infertility has been recommended for epidemiologic surveys (Larsen, 2005), however it is generally tied to the reference period of interest, i.e. the previous 12 months. In this study, although it was reported that pregnancy was attempted, whether the attempt took place within the previous 12 months was unknown.

Regardless of the definition, the present study suggests that over time, the prevalence of current infertility has increased in Canada. There are a number of possible explanations for this. The past several decades have seen a delay in conjugal union formation, resulting in couples starting to live together or getting married at older ages (Clark, 2007). This has led to a delay in childbearing, with women being older when first attempting pregnancy. In fact, the proportion of first-born children among women aged 35 and over has increased from 3% in 1984 (Statistics Canada, 1985) to 11% in 2008 (Statistics Canada, 2011a). Female age as a risk factor for infertility is well documented, with the risk of infertility increasing as female age increases (van Noord-Zaadstra et al., 1991; Gougeon, 2005; Swanton and Child, 2005). A similar result was found in the present study. Furthermore, not only did the prevalence of current infertility increase as female age increased, the increased odds of experiencing current infertility among couples with older female partners varied across parity. Age group of the female partner mattered for couples with lower parity (0 or 1 child) as they had significantly higher odds of experiencing current infertility when the female partner was aged 35–44 years versus 18–34 years. Conversely, multiparous couples had lower odds of experiencing current infertility regardless of the age group of the female partner, when compared with couples with fewer children and an older female partner. This interaction between female age and parity supports a link between delayed childbearing and an increased risk of experiencing current infertility.

In addition to the known impact of female age, factors such as obesity, smoking, alcohol use and sexually transmitted infections (STIs) have been shown to adversely affect female fecundity (Grodstein et al., 1994; Goldman et al., 2000; Kelly-Weeder and Cox, 2006; Brassard et al., 2008; Anderson et al., 2010). While direct links between lifestyle factors and the results from this study cannot be made, detrimental changes in these factors over time may be related to the observed increase in the prevalence of current infertility. Between 1981 and 2007–2009, the average measured BMI of women between 20 and 39 years of age increased from 22.5 to 25.9 kg/m2. At the same time, the proportion of women in this age group categorized as obese rose from 4 to 21% (Shields et al., 2010). Although the prevalence of daily or occasional smoking among women aged 20–44 years fell from 35% to about 20% between 1994 and 2010 (Statistics Canada, 1998a, 2010b), over the same period the rate of heavy drinking (five or more drinks at a time at least once a month) increased from 9 to 20% among women aged 20–34 years (Statistics Canada, 1998b, 2010b). Reported rates of STIs such as chlamydia and gonorrhea have risen, with the majority of cases being reported for women under 30 years of age. The chlamydia infection rate of 1999 increased 71% to 1824.3 per 100 000 in 2008 for women 20–24 years of age, while for the same age group the gonorrhea infection rate more than doubled to 166.3 per 100 000 over the same period (Public Health Agency of Canada, 2010). Of particular concern is that chlamydia is commonly asymptomatic, leading to both underreporting and increased risk of the spread of infection (Public Health Agency of Canada, 2010). Despite the presence of such factors known to be related to infertility, however, it is difficult to establish a cause-and-effect relationship in population studies.

Limitations

The three definitions used in this study to estimate the prevalence of current infertility are constructed variables and not clinical diagnoses. It is possible that some couples categorized as infertile may conceive beyond a 12-month period, while it is unknown to what extent those couples using birth control may have trouble conceiving. Furthermore, it was not possible to identify couples where the male and/or female partner had been sterilized, which precluded a more detailed analysis. Nonetheless, these prevalence estimates are generalizable to the study population and can be considered reliable and valid from the standpoint of estimating population-based prevalence (Stephen and Chandra, 2006).

Due to data limitations, it was not possible to examine factors such as obesity, smoking behavior, alcohol use, etc. in this study. The contribution of these and other factors to estimates of infertility prevalence require further investigation.

Conclusion

Current infertility is frequently defined as the inability to achieve a pregnancy after being exposed to the risk of conception for at least the previous 12 months. This study provides a current assessment of the prevalence of infertility among Canadian couples, according to three definitions of the risk of conception. The results show that regardless of the definition, the prevalence of current infertility has increased since the last time it was measured in Canada, and is associated with the age of the female partner and parity. Using relevant population-based data to estimate prevalence helps to inform both practice and program initiatives aimed at reducing the social, economic and health burdens of infertility.

Authors' roles

T.B. and J.L.C. contributed to the conception and design of the study. T.B. conducted the analysis, and all authors assisted in the interpretation of the results. T.B. and J.L.C. drafted the manuscript and all authors critically reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content and approved the final version submitted for publication.

Funding

This research was supported by funding from Assisted Human Reproduction Canada. Funding to pay the Open Access publication charges for this article was provided by Assisted Human Reproduction Canada.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Lindsay Patrick for her review and feedback on the manuscript. The authors also thank all who were involved in the development and production of the 2009–2010 Infertility component of the CCHS at Statistics Canada and Assisted Human Reproduction Canada.

References

- Abdi H. The Bonferonni and Šidák Corrections for Multiple Comparisons. In: Salkind N, editor. Encyclopedia of Measurement and Statistics. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Allen VM, Wilson RD, Cheung A. Pregnancy outcomes after assisted reproductive technology. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2006;173:220–233. doi: 10.1016/S1701-2163(16)32112-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson K, Nisenblat V, Norman R. Lifestyle factors in people seeking infertility treatment - A review. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2010;50:8–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-828X.2009.01119.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balakrishnan TR, Fernando R. The Prevalence of Infertility in Canada: Research Studies of the Royal Commission on New Reproductive Technologies. Ottawa: Minister of Supply and Services Canada; 1993. Infertility among Canadians: an analysis of data from the Canadian Fertility Survey (1984) and General Social Survey (1990) pp. 107–162. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya S, Porter M, Amalraj E, Templeton A, Hamilton M, Lee A, Kurinczuk J. The epidemiology of infertility in the North East of Scotland. Hum Reprod. 2009;24:3096–3107. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dep287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boivin J, Bunting L, Collins JA, Nygren KG. International estimates of infertility prevalence and treatment-seeking: potential need and demand for infertility medical care. Hum Reprod. 2007;22:1506–1512. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dem046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boivin J, Bunting L, Collins JA, Nygren KG. Reply: International estimates on infertility prevalence and treatment seeking: potential need and demand for medical care. Hum Reprod. 2009;24:2380–2383. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dem046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouzayen R, Eggertson L. In vitro fertilization: a private matter becomes public. Can Med Assoc J. 2009;181:243. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.091344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brassard M, AinMelk Y, Baillargeon J-P. Basic Infertility Including Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Med Clin North Am. 2008;92:1163–1192. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2008.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carson J. Family spending power. Perspect Labour Income. 2002;10:5–13. [Google Scholar]

- Chambers GM, Sullivan E, Ishihara O, Chapman M, Adamson G. The economic impact of assisted reproductive technology: a review of selected developed countries. Fertil Steril. 2009;91:2281–2294. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandra A, Stephen EH. Impaired Fecundity in the United States: 1982–1995. Fam Plan Perspect. 1998;30:34–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark W. Delayed transitions of young adults. Canadian Social Trends 2007. 2007;Winter:13–21. [Google Scholar]

- Deonandan R. The public health implications of assisted reproductive technologies. Chronic Dis Can. 2010;30:119–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dulberg CS, Stephens T. The Prevalence of Infertility in Canada: Research Studies of the Royal Commission on New Reproductive Technologies. Ottawa: Minister of Supply and Services Canada; 1993. The prevalence of infertility in Canada, 1991–1992: analysis of three national surveys; pp. 61–106. [Google Scholar]

- Evers J. Female subfertility. Lancet. 2002;360:151–159. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09417-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman MB, Missmer SA, Barbieri RL. Infertility. In: Goldman MB, Missmer SA, editors. Women and Health. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 2000. pp. 196–214. [Google Scholar]

- Gougeon A. The biological aspects of risks of infertility due to age: the female side. Rev Epidémiol Santé Publique. 2005;53:2S37–2S45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grodstein F, Goldman MB, Cramer DW. Body Mass Index and Ovulatory Infertility. Epidemiology. 1994;5:247–250. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199403000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunby J, Daya S on behalf of the IVF Directors Group of the Canadian Fertility and Andrology Society. Assisted reproductive technologies (ART) in Canada: 2001 results from the Canadian ART Register. Fertil Steril. 2005;84:590–599. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.03.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunby J, Bissonnette F, Librach C, Cowan L on behalf of the IVF Directors Group of the Canadian Fertility and Andrology Society. Assisted reproductive technologies in Canada: 2005 results from the Canadian Assisted Reproductive Technologies Register. Fertil Steril. 2009;91:1721–1730. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.02.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunby J, Bissonnette F, Librach C, Cowan L on behalf of the IVF Directors Group of the Canadian Fertility and Andrology Society. Assisted reproductive technologies (ART) in Canada: 2006 results from the Canadian ART Register. Fertil Steril. 2010;93:2189–2201. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.03.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunby J, Bissonnette F, Librach C, Cowan L on behalf of the IVF Directors Group of the Canadian Fertility and Andrology Society. Assisted reproductive technologies (ART) in Canada: 2007 results from the Canadian ART Register. Fertil Steril. 2011;95:542–547. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.05.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurunath S, Pandian Z, Anderson RA, Bhattacharya S. Defining infertility - a systematic review of prevalence studies. Hum Reprod Update. 2011;17:575–588. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmr015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzick DS, Swan S. The decline of infertility: apparent or real? Fertil Steril. 2006;86:524–526. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbert DL, Lucke JC, Dobson AJ. Infertility, medical advice and treatment with fertility hormones and/or in vitro fertilisation: a population perspective from the Australian Longitudinal Study on Women's Health. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2009;33:358–364. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-6405.2009.00408.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly-Weeder S, Cox CL. The impact of lifestyle risk factors on female infertility. Women Health. 2006;44:1–23. doi: 10.1300/j013v44n04_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen U. Research on infertility: which definition should we use? Fertil Steril. 2005;83:846–852. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2004.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macaluso M, Wright-Schnapp TJ, Chandra A, Johnson R, Satterwhite CL, Pulver A, Berman SM, Wang RY, Farr SL, Pollack LA. A public health focus on infertility prevention, detection, and management. Fertil Steril. 2010;93:16.e1–16.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.09.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchbanks PA, Peterson HB, Rubin GL, Wingo PA the Cancer and Steroid Hormone Study Group. Research on Infertility: Definition makes a difference. Am J Epidemiol. 1989;130:259–267. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Public Health Agency of Canada. Report on Sexually Transmitted Infections in Canada: 2008. 2010. Available at http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca. (29 August 2011, date last accessed)

- Rowe PJ, Comhaire FH, Hargreave TB, Mellows HJ. WHO Manual for the Standard Investigation and Diagnosis of the Infertile Couple. New York, USA: Cambridge University Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Sciarra J. Infertility: an international health problem. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 1994;46:155–163. doi: 10.1016/0020-7292(94)90230-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shields M, Tremblay MS, Laviolette M, Craig CL, Janssen I, Connor Gorber S. Fitness of Canadian adults: results from the 2007–2009 Canadian Health Measures Survey. Health Reports. 2010;21:21–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada. 1985. pp. 84–204. Births and Deaths 1984 Catalogue.

- Statistics Canada. Smoking Status, by Age Group and Sex. 1998a. CANSIM table #104–0027 Available at http://www.statcan.gc.ca. (29 August 2011, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada. Frequency of Drinking in the Past 12 Months, by Age Group and Sex. 1998b. CANSIM table #104–0031 Available at http://www.statcan.gc.ca. (29 August 2011, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada. Canadian Community Health Survey: Rapid Response on Infertility Complement to the User Guide—December 2010. 2010a. Available upon request through e-mail to hd-ds@statcan.gc.ca.

- Statistics Canada. Health Indicator Profile, Annual Estimates, by Age Group and Sex. 2010b. CANSIM table #105-0501 Available at http://www.statcan.gc.ca. (29 August 2011, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada. Births 2008. 2011a. Catalogue 84F0210X. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada. Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS) Annual Component User guide—2010 and 2009–2010 Microdata Files—June 2011. 2011b. Available at http://www.statcan.gc.ca/imdb-bmdi/document/3226_D7_T9_V8-eng.pdf. (15 September 2011, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- Stephen EH, Chandra A. Estimating infertility: not the last word. Fertil Steril. 2006;86:534. [Google Scholar]

- Swanton A, Child T. Reproduction and ovarian ageing. J Br Menopause Soc. 2005;11:126–131. doi: 10.1258/136218005775544200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thonneau P, Spira A. Prevalence of infertility: international data and problems of measurement. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1990;38:43–52. doi: 10.1016/0028-2243(91)90206-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Noord-Zaadstra BM, Looman CW, Alsbach H, Habbema JD, te Velde E, Karbatt J. Delaying childbearing: effect of age on fecundity and outcome of pregnancy. Br Med J. 1991;302:1361–1365. doi: 10.1136/bmj.302.6789.1361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb S, Holman D. A survey of infertility, surgical sterility and associated reproductive disability in Perth, Western Australia. Aust J Public Health. 1992;16:376–381. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-6405.1992.tb00084.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]