Abstract

Objective:

Examine how patient-clinician information engagement (PCIE) may operate through feeling informed to influence patients' treatment decision satisfaction (TDS).

Methods:

Randomly drawn sample (N=2013) from Pennsylvania Cancer Registry, comprised of breast, prostate and colon cancer patients completed mail surveys in Fall of 2006 (response rate = 64%) and Fall of 2007. Of 2013 baseline respondents, 85% agreed to participate in follow-up survey (N=1703). Of those who agreed, 76% (N=1293) completed follow-up surveys. The sample was split between males and females. The majority of participants were White, over the age of 50, married, and with a high school degree. Most reported having been diagnosed with in situ and local cancer.

Results:

PCIE was related to concurrent TDS (β=.06) and feeling informed (β=.15), after confounder adjustments. A mediation analysis was consistent with PCIE affecting TDS through feeling informed. Baseline PCIE predicted feeling informed (β=.04) measured one year later, after adjustments for baseline feeling informed and other confounders. Feeling informed was related to concurrent TDS (β=.35) after confounder adjustment and follow-up TDS (β=.13) after baseline TDS and confounder adjustment.

Conclusion:

Results suggest PCIE affects TDS in part through patients' feeling informed.

Practice Implications:

PCIE may be important in determining patients' level of feeling informed and TDS.

Keywords: Patient-clinician communication, treatment decision satisfaction, cancer, feeling informed

1. Background

We know that many newly-diagnosed cancer patients are heavily involved with information gathering both from their physicians and from other sources [1, 2]. We also know that treatment satisfaction is related to treatment adherence and good health outcomes [3]. However, we do not know whether and how information gathering from and exchanged with physicians is related to treatment satisfaction. Are those who are highly engaged in patient-physician communication more likely to be satisfied with their treatment decision because they feel well informed? Or are they less likely to be satisfied because their information engagement with information from their physician raises uncertainties or undermines their confidence in their treating physicians?

Patient satisfaction with health care services is associated with improved health outcomes and is a predictor of important health behaviors, such as adherence with prescribed treatment plans and regimens [4-6]. More specifically, treatment satisfaction may be associated with treatment-related behaviors such as compliance [7, 8], and predictive of psychosocial outcomes [9] especially among patients suffering from chronic illnesses including cancer.

Given current changes in the U.S. health care system the path to higher treatment satisfaction may have become more complicated. The system is moving from a traditional “paternalistic” model of health care towards one which attempts to engage patients as active participants in their health [10-14]. This model requires patients to be well informed, for example about treatment benefits and risks, so that they have a basis for active participation. While promising treatments have improved cancer survival rates, functional status and quality-of-life, adverse side effects are common and every intervention is associated with a unique risk/benefit tradeoff, making treatment decisions complicated and difficult [15].

The available evidence supports an argument for positive effects of patient-clinician communication on treatment satisfaction. “Patient-centered” communication, in which providers strive to personalize treatment information and service delivery, is relevant to valued outcomes [16]. These outcomes include higher general satisfaction, adherence to treatment regimens and improved health outcomes [17, 18] and also greater treatment decision satisfaction [19, 20]. However, even if this evidence is accepted at face value, it is evidence about one form of information engagement (with the clinician) and it does not provide much evidence about how the effects come about. If better clinician-patient communication is among the ways to achieve treatment satisfaction, effective transfer of information from clinician to patient is challenging and often problematic, as informational needs, desires and capacities vary among patients [15, 21-23] and skills and time for engaging in such patient-centered communication varies among clinicians.

Patient-centered communication includes as a central component the exchange of information. Information exchange has been identified as a critical function of patient-centered communication [24, 16]. In this study we focus on what might be considered a subset of information exchange, the extent to which the patients recall actively seeking information from their clinicians, and (to a lesser extent) their recall of reception of information from their clinicians. We have called this information engagement to distinguish it from the subtler construct of information exchange which likely incorporates a fuller dimension of dialogue between patients and clinician, although we might speculate that such engagement is associated with, and is an indicator of the fuller forms of exchange.

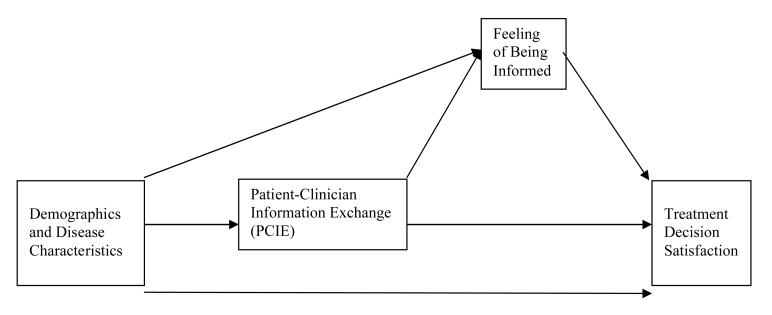

Thus the underpinnings for this study are three: treatment satisfaction has worthwhile outcomes; current shifts in the U.S. health care system appear to place a premium on well-informed patients; patient-clinician communication appears to be related to treatment satisfaction. In this study we seek to take this literature further. Is patient-clinician information engagement specifically associated with treatment satisfaction? Also, if it is true that patient-clinician information engagement is associated with treatment satisfaction, what is the mechanism of effect? Does patient-clinician information engagement produce effects because it increases the feeling of being informed and then treatment satisfaction? We propose that this mechanism is likely (see Figure 1.)

Figure I.

Proposed Model of Mediation Effects

In general, research suggests that patient-clinician communication [25] and informed choice [26, 27] are associated with treatment decision. However, no study to this date has tested if patient-clinician information engagement (our surrogate for patient clinician information exchange) indirectly affects treatment satisfaction because it increases the level of certainty surrounding the decisions made about treatments. This study provides three major advances over prior work: it makes use of a representative sample of cancer patients from Pennsylvania; many earlier studies have been limited to convenience samples typically drawn from physician offices. Second it explores the fit of specific mechanisms of effect as displayed in Figure 1 using cross-sectional data. Third, because attributing causality through cross-sectional data is problematic, the study identifies the causal direction of influence among the principal variables of interest using longitudinal data. We expect that a formal test of mediation will show:

Patient-clinician information engagement (PCIE) is positively associated at the cross-sectional level with feeling informed independently from basic demographic and disease variables.

Patient-clinician information engagement (PCIE) is positively associated at the cross-sectional level with treatment decision satisfaction independently from basic demographic and disease variables.

Feeling informed partially mediates the cross-sectional association between PCIE and treatment decision satisfaction adjusting for basic demographic and disease variables.

Additionally, we expect a test of causal direction to indicate:

4. Patient-clinician information engagement (PCIE) at baseline positively predicts feeling informed at the one-year follow-up adjusting for basic demographic and disease variables.

5. Feeling informed at baseline positively predicts treatment decision satisfaction at the one-year follow-up adjusting for basic demographic and disease variables.

2. Methods

2.1 Participants

Breast (female only), prostate (male only), and colorectal cancer patients were stratified by cancer and randomly sampled from a list of patients diagnosed in 2005 in Pennsylvania provided by the Pennsylvania Cancer Registry (PCR). Cancer cases are legally reportable to the PCR within six months of diagnosis. The sampling frame, drawn in the Fall of 2006, included approximately 95% of all cases that would eventually be reported to the PCR. To increase statistical power for some analyses, we over-sampled stage four cancer patients and African American patients. The follow-up survey was administered in the Fall of 2007 to the sample drawn in 2006.

2.2 Description of baseline sample

Table 1 presents the description of the sample at baseline and follow-up. As the sample remained fairly consistent from baseline to follow-up, we focus on the characteristics of the sample at baseline where respondents ranged in age from 24 to 105 years. Almost 88% of respondents were above the age of 50. The sample was split roughly equally between male and female subjects. The majority of participants were White, married, and with a high school degree. Close to 62% of respondents reported having been diagnosed with in situ and local cancer.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics - Baseline versus Follow-Up Respondents

| Sample Characteristics | Mean | S.D. | % | Mean | S.D. | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline (N=2013) | Follow-Up (N=1214) | |||||

| Age | ||||||

| 24-50 years | 12 | 12 | ||||

| 51-60 years | 22 | 24 | ||||

| 61-70 years | 28 | 29 | ||||

| 71-80 years | 25 | 24 | ||||

| 81-105 years | 13 | 11 | ||||

| Male | 49 | 48 | ||||

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| White | 86 | 89 | ||||

| Non-white | 14 | 11 | ||||

| Education | ||||||

| Eighth grade or less | 5 | 3 | ||||

| Some high school | 11 | 9 | ||||

| High school diploma | 40 | 40 | ||||

| Some college/2 year degree | 22 | 23 | ||||

| College graduate | 22 | 25 | ||||

| Marital Status | ||||||

| Married | 69 | 72 | ||||

| Not married | 31 | 26 | ||||

| Cancer | ||||||

| Breast | 34 | 35 | ||||

| Prostate | 32 | 33 | ||||

| Colon | 34 | 32 | ||||

| Stage of Cancer | ||||||

| In Situ and local | 62 | 64 | ||||

| Regional Spread | 22 | 23 | ||||

| Metastasis | 16 | 13 | ||||

| Self-perceived Health Status | 2.14 | .87 | 2.24 | .86 | ||

2.3 Study Design and Procedure

A 61-question paper survey was mailed to cancer patients residing in Pennsylvania. The survey included questions regarding patient characteristics, knowledge and experience with cancer treatments, and information-seeking and scanning about cancer and treatments. The survey was developed using a combination of standard questions and questions developed for the sole purpose of this research. To facilitate patient understanding, a pilot test of the survey was administered to identify and revise question wording or format. The final version of the survey consisted of five general sections: demographic characteristics, patient characteristics (i.e. psychosocial, etc.), information-seeking and scanning about treatments and cancer in general, treatment knowledge, quality-of-life questions. For the purposes of the present study, we focused on the first four sections.

Following pilot testing and revisions using interviews with cancer patients, the survey was finalized. Data were collected in two waves in the fall of 2006. During the first wave in September 2006, participants randomly received either a $3 or $5 monetary incentive and a short or long version of the survey. Based on the response rates in the first wave of data collection, during the second data collection wave in November, 2006, all participants received $5 and a long version of the survey. Mailing procedures were based on [28] and were the same for each data collection wave. Each survey was tailored according to the type of the patient's cancer (i.e., use of breast, colon, or prostate cancer on the survey cover as appropriate). The long version of the survey included 61 questions; the short version 33 questions. The follow-up survey was comprised of 54 questions, including those relevant to this study.

2.4 Measures

Demographics

Age and education were categorized. Marital status was dichotomized (member of an unmarried or married couple versus divorced, separated, or never married). Race and ethnicity also was dichotomized (white respondent versus other than white race or ethnicity: 13% of the non-white respondents were African-American).1

Patient Characteristics

A standard single-item question in 5-point Likert-style format assessed self-perceived health status: “In general how would you rate your overall health now?” with possible responses ranging from “excellent” to “poor.” Because patients only received treatment questions relevant to their cancer and to take advantage of the full sample, we calculated the number of treatments received across cancers by computing the mean number of treatments received within each cancer and then converting the means into z-scores. This allowed characterization of patients as to the tendency to get more or fewer treatments than others with the same cancer. Cancer stage was coded as a three level ordinal variable (in situ; regional; metastatic). Cancer type was coded into dummy variables, with colon cancer as the reference category.

Principal Variables

Patients' feeling of being informed was measured at baseline using four items in a 5-point Likert scale (α = 0.89) with answer options ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree” in response to the following statements: 1) “I made an informed choice about my treatment” 2) “I was aware of the choices I had to manage my cancer” 3) “I knew the benefits of the treatments for my cancer” 4) “I knew the risks and side effects of the treatments for my cancer.” At follow-up, feeling informed was measured using a 5-point single item measure “I made an informed choice about my treatment” with answer options ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”. The dependent variable, satisfaction with decisions made about cancer treatment, was measured at baseline and follow-up with a single-item question including answer options ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”: “I am satisfied with the decisions made about my treatment.”

We assessed patient-clinician information engagement at baseline with an eight-item scale (α=0.78). To establish the time frame, questions at baseline were anchored with the following text: “Think back to the first few months after you were diagnosed with your cancer.” At the one year follow-up, this text was replaced with “in the past 12 months.” The items drew yes-no answers to the following questions: “In making decisions about what treatments to choose, did you actively look for information about treatments from your treating doctor?; In making decisions about what treatments to choose, did you actively look for information about treatments from other doctors or health professionals?; Did you actively look for information related to your cancer from your treating doctor?; Did you actively look for information related to your cancer from other doctors or health professionals? ; Did you discuss information from other sources with your treating doctor?; Did your treating doctor suggest that you get information from other sources?; Did you actively look for quality of life information from your treating doctor? ; Did you actively look for quality of life information from other doctors or health professionals?”. The mean of each item was then centered and converted into z-scores, and summed to create an overall scale. We measured patient-clinician information engagement at follow-up with a six-item scale (α=0.72). The items drew yes-no answers to the following questions: Did you actively look for information related to your cancer from your treating doctor?; Did you actively look for information related to your cancer from other doctors or health professionals? ; Did you discuss information from other sources with your treating doctor?; Did your treating doctor suggest that you get information from other sources?; Did you actively look for quality of life information from your treating doctor? ; Did you actively look for quality of life information from other doctors or health professionals?”. As with the baseline measure, the mean of each item was then centered and converted into z-scores, and summed to create an overall scale.

2.5 Statistical Analysis

Multiple imputation was used to address missing data following procedures recommended by Allison [29] using STATA 10 and the ICE program [30]. That procedure creates fifteen datasets with imputed values. The MIM program was then used to generate parameter estimates by averaging across the fifteen datasets. We also applied post-stratification weights to the data to reflect the distribution of cases in the PCR within each cancer on age, sex, marital status, date of diagnosis, race-ethnicity, and stage of disease. Analyses used the Survey programs in STATA 10 to assure appropriate estimation of standard errors, given the use of weights.

As discussed earlier, in addition to testing the relationship between PCIE and treatment decision satisfaction, the aim of this study was to test a proposed mechanism suggesting that PCIE affected cancer patients' treatment decision satisfaction by increasing their feeling of being informed. To test this mechanism, we performed a formal test of mediation using the joint significance test [31] rather than the standard guidelines [32] as the former provides the best balance between statistical power and Type I errors [31]. An inference of mediation is supported if (a) the independent variable is significantly related to the mediating variable, and (b) if the mediating variable is significantly related to the dependent variable upon controlling for the independent variable. To specifically establish if the indirect effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable was significantly different from zero we used Sobel's test statistic [33]. The mediation test in this study was conducted using a series of standard multiple regressions at the cross-sectional level controlling for gender, race, marital status, education, age, cancer type, cancer stage, self-perceived health status, and number of treatments received.

The decision to test the model cross-sectionally rests on two needs: the availability of a larger sample which maximizes statistical power to detect effects and the likelihood that some effects occur quickly and would be most easily seen if all measures are taken simultaneously. Statistical adjustments for measured potential confounders reduce the risk that observed associations between principal variables are merely artifacts of the influence of such confounders. On the other hand, cross-sectional analyses are of limited value in supporting causal claims; observed associations do not permit disentangling which of the associated variables is cause and which effect (or whether there is some mutual causation). Supplementing cross-sectional analysis with longitudinal analyses addresses this causal order issue directly. If, for example, prior PCIE can be shown to account for subsequent feeling of being informed while adjusting for baseline feeling of being informed (and other baseline confounders) then the claim that influence flows from PCIE to feeling informed is additionally supported. Thus, we present the results testing the proposed model of effect in two stages. The first stage shows the formal test of mediation using cross-sectional data to maximize statistical power and detection of effects. However, to address concerns often raised when inferring causal relationships from cross-sectional associations, the second stage demonstrates tests of causal direction using longitudinal data.

3. Results

The baseline response rate was 61% for colorectal cancer participants, 68% for breast cancer participants, and 64% for prostate cancer participants at baseline. These response rates were calculated with the American Association for Public Opinion Research formula RR4 [35]. The raw response rates were 75% for colorectal cancer participants, 79% for breast cancer participants, and 77% for prostate cancer participants at follow-up. The distribution of the principal variables, demographics, and patient characteristics remained fairly stable upon applying weights and imputing values. The total final sample at baseline was 2013 and 1214 at follow-up after performing the multiple imputation procedure.

As seen in Table 1, the baseline sample mean score for self-perceived health status scale was 2.14 (S.D. = 0.87, range = 1 to 4). Table 2 shows that participants in the baseline sample reported moderately high levels of treatment decision satisfaction, indicated with a sample mean score of 3.36 (S.D. = 0.75, range = 1 to 4). The sample mean score for feeling informed was 13.03 (S.D. = 2.57, range = 1 to 16).

Table 2.

Primary Variables - Baseline versus Follow-Up Respondents

| Variables | Mean | S.D. | Mean | S.D. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline (N=2013) |

Follow-Up (N=1214) |

|||

| PCIE | 0.00 | 0.63 | 0.06 | 0.63 |

| Feeling Informed | 13.03 | 2.57 | 13.32 | 2.45 |

| Treatment Decision Satisfaction | 3.36 | 0.75 | 3.43 | 0.72 |

Referring again to Table 1, respondents at follow-up did not differ substantially on the variables which had been assessed at baseline. The sample mean score for self-perceived health status scale was 2.24 (S.D. = 0.86). In Table 2, we see that follow-up participants generally tended to indicate a moderately high level of treatment decision satisfaction seen with baseline participants, where the sample mean score for the treatment decision satisfaction scale was 3.43 (S.D. = 0.72). The sample mean score for feeling informed was 13.32 (S.D. = 2.45), similar to baseline participants. Additionally we see that participants at follow-up reported slightly higher PCIE than baseline participants (sample mean score for follow-up = 0.06, S.D. = 0.63; sample mean score for baseline = 0.00, S.D. = 0.63).

Table 3 provides information regarding how retained participants changed from baseline to follow-up on principal variables measured at both time points. Treatment decision satisfaction scores for retained participants remained relatively unchanged over time, however it should be noted that their feeling of being informed noticeably decreased from baseline to follow-up, falling from a mean of 13.32 (S.D. = 2.45; range 1 to 16) to a mean of 2.27 (S.D. = 1.20; range 1 to 4), perhaps because respondents were two years out from diagnosis at the follow-up and were less involved with information about their cancer. Table 4 shows the correlations among the primary variables. All primary variables were statistically significant at the 0.01 level or less and correlated in the expected direction.

Table 3.

Sample Characteristics of Retained Respondents (N=1214)

| Variables | Mean | S.E. | Mean | S.E. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline Scores | Follow-Up Scores | |||

| PCIE | 0.06 | 0.63 | 0.00 | 0.65 |

| Feeling Informed | 13.32 | 2.45 | 2.27 | 1.20 |

| Treatment Decision Satisfaction | 3.43 | 0.72 | 3.39 | 0.78 |

Table 4.

Correlation Matrix of Primary Variables (N=1214)

| PCIE (Baseline) |

PCIE (Follow- Up) |

Feeling Informed (Baseline) |

Feeling Informed (Follow-Up) |

Satisfaction (Baseline) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCIE (Follow-Up) | 0.43 | ||||

| Feeling Informed (Baseline) | 0.21 | 0.04 | |||

| Feeling Informed (Follow- Up) |

0.17 | 0.03 | 0.83 | ||

| Satisfaction (Baseline) | 0.11 | −0.03 | 0.39 | 0.33 | |

| Satisfaction (Follow-Up) | 0.05 | −0.03 | 0.28 | 0.24 | 0.45 |

All displayed variables are statistically significant at p < .01 or less.

3.1 Formal Test of Mediation

The proposed model of mediation effects presented in Figure 1 involved three specific propositions. Table 5 shows results of a series of regression models which provide tests for these propositions. The first proposition required that PCIE relate to feeling informed above and beyond the effects of demographic and disease variables. Model 1 shows the effect of demographic and patient characteristics on feeling informed. Model 2 adds the effect of PCIE and shows a significant effect of PCIE on feeling informed at the cross-sectional level, thus supporting the first proposition.

Table 5.

Formal Test of Mediation (N=2013)

| Predictor | Model 1 Feeling Informed |

Model 2 Feeling Informed |

Model 3 Satisfaction |

Model 4 Satisfaction |

Model 5 Satisfaction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | |||||

| Race | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.06 * | 0.06 * | 0.04 |

| Education | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.00 | −0.01 | −0.02 |

| Gender | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.06 | −0.06 | −0.06 |

| Age | −0.16 *** | −0.13 *** | −0.06 * | −0.05 | 0.00 |

| Marital Status | 0.00 | −0.01 | 0.08 ** | 0.08 ** | 0.08 ** |

| Treatments Received | −0.03 | −0.04 | −0.04 | −0.04 | −0.03 |

| Stage | −0.05 | −0.05 | −0.07 * | −0.07 * | −0.05 * |

| Breast | 0.04 | 0.02 | −0.06 | −0.07 * | −0.08 * |

| Prostate | 0.07 | 0.03 | −0.04 | −0.05 | −0.06 |

| Health Status | 0.26 *** | 0.26 *** | 0.22 *** | 0.22 *** | 0.13 *** |

| Step 2 | |||||

| PCIE | 0.15 *** | 0.06 * | 0.00 | ||

| Step 3 | |||||

| Feeling Informed | 0.35 *** | ||||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.12 | 0.14 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.18 |

p <.05;

p<.01;

p<.001.

Displayed values are standardized β coefficients, and explained adjusted variances (in bold).

Model 3 shows the effect of demographic and patient characteristics on treatment decision satisfaction, where we see that race, age, martial status, cancer stage and health status are significantly associated with treatment decision satisfaction. It should be noted that the effects of all but marital status are attenuated upon adding PCIE and feeling informed, suggesting that some of the effects of these background variables on TDS works through PCIE and/or feeling informed. Model 4 adds the effect of PCIE to test the second proposition that PCIE relates to treatment decision satisfaction. We see support for this proposition as PCIE is positively associated with treatment decision satisfaction at the cross-sectional level. However, upon adding feeling informed into the equation displayed in Model 5, we see that this association of PCIE with treatment decision satisfaction disappears. In contrast, feeling informed is strongly associated with treatment decision satisfaction adjusting for demographic and disease variables and PCIE. This effect of feeling informed on treatment decision satisfaction supports the third proposition requiring that feeling informed associate with treatment decision satisfaction over and above the effect of demographic and disease variables and PCIE. Taken together, these results suggest a partial mediation effect in which feeling informed explains in part the association between PCIE and treatment decision satisfaction. Additionally, according to Sobel's test the indirect effect of PCIE on treatment decision satisfaction through feeling informed was statistically significant (Sobel test, 5.10, p < .000) and provides further evidence for partial mediation effect. Interactions between the three different cancers and PCIE were also tested and showed no significant effect on either feeling informed or treatment decision satisfaction, supporting a claim that the effects reported here were independent of which cancer a patient had.

In sum, PCIE appears to have a positive and direct association with feeling informed and treatment decision satisfaction at the cross-sectional level. Upon adding feeling informed into the equation, the cross-sectional association between PCIE and treatment decision satisfaction disappears, suggesting an effect of partial mediation. However based on these results, the direction of causal influence among PCIE, feeling informed and treatment decision satisfaction remains unclear.

3.2 Establishing Causal Direction

We conducted a separate analysis (test of causal direction) using longitudinal data to establish if our contention that PCIE influenced feeling informed (proposition 4), which then in turn affected treatment decision satisfaction (proposition 5) was correct. Table 6 presents results of two regressions testing these points. Referring to Model 1, we see a significant effect of PCIE on feeling informed at follow-up, which lends support to the fourth proposition requiring that PCIE relates to feeling informed over and above the effects of demographic and disease variables and feeling informed at baseline. This shows that the observed cross-sectional association between PCIE and feeling informed does not merely reflect effects of feeling informed on reports of information engagement with physicians; the lagged effects is consistent with the causal direction of influence running from PCIE to feeling informed.

Table 6.

Test of Causal Direction (N=1214)

| Predictor | Model 1 Feeling Informed at Follow-Up |

Model 2 Satisfaction at Follow-Up |

|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | ||

| Age | −0.02 | 0.03 |

| Education | 0.13 *** | 0.02 |

| Marital Status | 0.01 | 0.03 |

| Race | 0.07 * | 0.02 |

| Gender | 0.03 | −0.02 |

| Health Status | 0.04 | 0.06 |

| Stage | −0.07 *** | −0.02 |

| Breast | 0.00 | −0.03 |

| Prostate | 0.01 | −0.02 |

| Treatments Received | −0.01 | −0.03 |

| PCIE (Baseline) | 0.04 * | 0.01 |

| Feeling Informed (Baseline) | 0.18 *** | 0.13 *** |

| Satisfaction (Baseline) | 0.37 *** | |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.19 | 0.21 |

p <.05;

p<.01;

p<.001.

Displayed values are standardized β coefficients, and explained adjusted variances (in bold).

In Model 2, the same predictors were regressed on treatment decision satisfaction at follow-up, supporting an argument that the direction of causal influence runs from feeling informed to treatment decision satisfaction. This provided support for the fifth proposition which required that feeling informed predict treatment decision satisfaction at follow-up adjusting for demographic and disease variables, PCIE, and treatment decision satisfaction at baseline. Additionally, a series of tests not presented here were performed in order to consider the possibility that the observed cross-sectional association might have been due to effects of TDS or feeling informed on PCIE rather than the effects of PCIE on those variables. One model tested if feeling informed at baseline predicted PCIE at follow-up controlling for PCIE at baseline and confounders, and another model tested if treatment decision satisfaction at baseline predicted feeling informed at follow-up controlling for feeling informed at baseline and confounders. The results from these tests failed to show significant evidence for reverse causation; this provides additional support for the claim that PCIE is the influential variable in these relationships. In sum, these results provide evidence for the direction of causal influence being such that PCIE positively predicts feeling informed, which then positively predicts treatment decision satisfaction, helping reduce concerns about the question of causal direction inherent in cross-sectional data.

4. Discussion and conclusion

4.1 Discussion

The main aim of this study was to investigate whether PCIE directly influences treatment decision satisfaction for cancer patients, through the feeling of being informed. The results presented here support our expectation that PCIE is related to treatment decision satisfaction and that this relation is partially mediated by feeling informed. Additionally, our results suggest that the direction of causal influence is such that PCIE predicts feeling informed, which then in turn predicts treatment decision satisfaction. This finding further supports cross-sectional associations seen between PCIE, feeling informed and treatment decision satisfaction.

Among all the variables tested in our model, PCIE emerged as the strongest predictor of feeling informed cross-sectionally as well as longitudinally. Other studies that investigated patients' perception of patient-clinician communication more broadly suggest that this can have profound effects on treatment decision satisfaction [19, 20]. In a similar way, feeling informed was the strongest predictor of treatment decision satisfaction. The feeling of having made an informed choice has been shown to be significantly associated with treatment decision satisfaction [26, 27]. There are also some results here to suggest that some populations may benefit from interventions aimed at improving information engagement in so far as it relates to feeling informed. Specifically, the results here show small but significant differences in treatment satisfaction based on race, age, cancer stage and health status, which weaken or disappear with PCIE and feeling informed.

Although the study presents a strong argument for causal order and partial mediation among the variables of interest, a few limitations within the study should be considered. First, the effect sizes as seen by the betas in our equations are rather small in magnitude [34]. Second, this study relied on self-reported data, and focused on patients with three common types of cancer. All subjects were residents of Pennsylvania. Thus, the applicability of results presented to other chronic illnesses and patient populations is not known. Third, the measure of PCIE was constructed specifically for the objectives of this study, and only measures whether engagement with information occurred and not the degree with which it occurred. In this sense it remains a measure of breadth rather than depth. Further investigation into factors not measured here, such as the level of patients' trust in their doctor or physician, and its role regarding PCIE, may further inform the theory tested in this study. Other avenues for research may entail the construction of a comprehensive model to predict the feeling of being informed and the investigation of treatment decision satisfaction in non-chronic or non-life threatening afflictions.

4.2 Conclusion

In conclusion, this study highlights the importance of PCIE and offers a relevant initial analysis of the way in which PCIE potentially impacts the feeling of being informed, and ultimately treatment decision satisfaction. Although the study focuses on cancer, it also might provide useful insights into the feeling of being informed and treatment decision satisfaction of patients with other chronic diseases. Future studies may seek to investigate the applicability of these findings to other health contexts.

4.3 Practice Implications

The recent shift towards patient empowerment in medical-decision making has spawned much interest in ways to maximize overall patient satisfaction. In a more specific context, treatment decision satisfaction carries many implications for improving health care delivery and aiding health care providers more effectively treat patients with chronic diseases, such as cancer. While the importance of fulfilling the informational needs of patients has been proclaimed in many studies, none have proposed a mechanism for how the way patients engage with information about their cancer impacts treatment decision satisfaction. Based on the findings presented here, physicians and health professionals may consider increasing patients' engagement with information about their cancer as it may help patients feel more informed and increase treatment decision satisfaction.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Katrina Armstrong, Stacy Gray, Angel Ho, Bridget Kelly, Chul-joo Lee, Nehama Lewis, Rebekah Nagler, Susana Ramirez, Anca Romantan, Aaron Smith-McLallen, and Norman Wong for their insightful comments on earlier drafts of the manuscript and/or contributions to instrument development, data collection, and coding, and to Robin Otto, Craig Edelman and personnel at the Pennsylvania Cancer Registry for collaboration on sample development. The Pennsylvania Department of Health specifically disclaims responsibility for any analyses, interpretations or conclusions. The authors wish to acknowledge the funding support of the National Cancer Institute's Center of Excellence in Cancer Communication (CECCR) located at the Annenberg School for Communication, University of Pennsylvania (P50-CA095856-05).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Less than 1% of non-white respondents were of Asian, American Indian, Native Hawaiian or other descent. Among all respondents, 3% considered themselves to be Hispanic or Latino, and of these respondents the majority also identified themselves as white.

Contributor Information

Lourdes S. Martinez, Annenberg School For Communication University of Pennsylvania, USA.

J. Sanford Schwartz, Department of Medicine and The Wharton School University of Pennsylvania, USA.

Derek Freres, Annenberg School For Communication University of Pennsylvania, USA.

Taressa Fraze, Annenberg School For Communication University of Pennsylvania, USA.

Robert C. Hornik, Annenberg School For Communication University of Pennsylvania, USA

References

- 1.Nagler RH, Gray SW, Romantan A, Kelly BJ, DeMichele A, Armstrong K, Schwartz JS, Hornik RC. Early stage colorectal cancer patients less prone to seek cancer information than breast and prostate cancer patients: Results from a population-based survey. under review. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rutten LJF, Arora NK, Bakos AD, Aziz N, Rowland J. Information needs and sources of information among cancer patients: A systematic review of research (1980-2003) Patient Educ Couns. 2005;57:250–61. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2004.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hoffman RM, Hunt WC, Gilliland FD, Stephenson RA, Potosky AL. Patient satisfaction with treatment decisions for clinically localized prostate carcinoma. Results from the prostate cancer outcomes study. Cancer. 2003;97:1653–62. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Albrecht G, Hoogstraten J. Satisfaction as a determinant of compliance. Comm Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1998;26:139–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1998.tb01940.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCracken LM, Klock A, Mingay DJ, Asbury JK, Sinclair DM. Assessment of satisfaction with treatment for chronic pain. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1997;14:292–9. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(97)00225-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weaver M, Patrick DL, Markson LE, Martin D, Frederic I, Berger M. Issues in the measurement of satisfaction with treatment. Am J Manag Care. 1997;3:579–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kovac JA, Patel SS, Peterson RA, Kimmel PL. Patient satisfaction with care and behavioral compliance in end-stage renal disease patients treated with hemodialysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2002;39:1236–44. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2002.33397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wright S. Patient satisfaction in the context of cancer care. Irish J Psychol. 1998;19:274–82. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hart SL, Latini DM, Cowan JE, Carroll PR. Fear of recurrence, treatment satisfaction, and quality of life after radical prostatectomy for prostate cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2008;16:161–9. doi: 10.1007/s00520-007-0296-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Houston TK, Ehrenberger HE. The potential of consumer health informatics. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2001;17:41–8. doi: 10.1053/sonu.2001.20418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grove A. The X-factor. J Amer Med Assoc. 1998;280:1294. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Levine SR. Consumer-driven health care: A path to achieving shared goals. Physician Exec. 2000;26:10–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rossiter J. Web watch. Health Manag Technol. 2000;21:76. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnson JD. Cancer-related information seeking. Hampton Press, Inc; Cresskill, NJ: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Siminoff LA, Fetting JH, Abeloff MD. Doctor-patient communication about breast cancer adjuvant therapy. J Clin Oncol. 1989;7:1192–200. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1989.7.9.1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Epstein RM, Street RL. Patient Centered Communication in Cancer Care. Promoting Healing and Reducing Suffering. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. NIH. NCI. 2007 Accessed April 18, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cecil DW, Killeen I. Control, compliance, and satisfaction in the family practice encounter. Fam Med. 1997;29:653–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rao JK, Weinberger M, Kroenke K. Visit-specific expectations and patient-centered outcomes: a literature review. Arch Fam Med. 2000;9:1148–55. doi: 10.1001/archfami.9.10.1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wong F, Stewart DE, Dancey J, Meana M, McAndrews MP, Bunston T, Cheung AM. Men with prostate cancer: Influence of psychological factors on informational needs and decision making. J Psychosom Res. 2000;49:13–9. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(99)00109-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Armstrong K, Weber B, Ubel PA, Peters N, Holmes J, Schwartz JS. Individualized survival curves improve satisfaction with cancer risk management decisions in women with brca1/2 mutations. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:9319–28. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.06.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rimer B, Jones WL, Keintz ML, Catalano RB, Engstrom PF. Informed consent: A critical step in cancer patient education. Health Educ Q. 1984;10(Suppl):S30–S42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Degner LF, Kristjanson LJ, Bowman D, Sloan LA, Carriere O'Neil KC, Bilodeau B, Watson P, Mueller B. Information needs and decisional preferences in women with breast cancer. J Amer Med Assoc. 1997;277:1485–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ravdin PM, Siminoff LA, Harvey JA. Survey of breast cancer patients concerning their knowledge and expectations of adjuvant therapy. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:515–21. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.2.515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee RG, Garvin T. Moving from information transfer to information exchange in health and health care. Soc Sci Med. 2003;56:449–64. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00045-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Berry DL, Ellis WJ, Russell KJ, Blasko JC, Bush N, Blumenstein B, Lange PH. Factors that predict choice and satisfaction with decision in men with localized prostate cancer. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2006;5:219–26. doi: 10.3816/CGC.2006.n.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.O'Conner A, O'Brien-Pallas L. Decisional Conflict. In: McFarland G, McFarlane E, editors. Nursing Diagnosis and Intervention. CV Mosby; Ontario, Canada: 1989. p. 573. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Holmes-Rovner M, Kroll J, Schmitt N, Rovner DR, Breer ML, Rothert ML, Padoni G, Talaczyk G. Patient satisfaction with health care decisions: The satisfaction with decision scale. Med Decis Making. 1996;16:58–64. doi: 10.1177/0272989X9601600114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dillman DA. Mail and Internet Surveys: The Tailored Design Method. Wiley; New York: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Allison PD. Sage University Papers Series on Quantitative Applications in the Social Sciences, 7-136. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2000. Missing data. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Royston P. Multiple imputation of missing values. Stata Journal. 2004;4:227–41. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mackinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffmann JM, West SG, Sheets V. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychol Methods. 2002;7:83–104. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986;51:1173–82. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sobel ME. Asymptotic confidence intervals for indirect effects in structural equations models. In: Leinhart S, editor. Sociological methodology 1982. Jossy-Bass; San Francisco: 1982. pp. 290–312. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd edition Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Hillsdale, NJ: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 35.American Association for Public Opinion Research (AAPOR) Standard Definitions: Final Dispositions of Case Codes and Outcome Rates for Surveys. 4th ed. AAPOR; Lenexa, Kansas: 2006. [Google Scholar]