Abstract

Objective

To explore conceptions of continuity of care among family physicians in traditional practices, family medicine–trained physicians working in episodic care, and family medicine residents to better understand the emotional effects on physicians of establishing long-term relationships with patients as a starting point for developing a tool to measure the qualitative connections between physicians and their patients.

Design

Qualitative descriptive study using focus groups.

Setting

Traditional family practice, family medicine residency training, and episodic-care settings in Kingston, Ont.

Participants

Three groups of first-year family medicine residents (n = 18), 2 groups of family physicians in established traditional practice (n = 9), and 2 groups of family physicians working in episodic-care settings (n = 10).

Methods

Using focus groups, a semistructured discussion guide, and a phenomenologic approach, we explored residents’ and practising physicians’ conceptions about continuity of care, predominantly exploring the emotional effects on physicians of providing care for a group of patients over time.

Main findings

Providing care for patients over time and developing a deep knowledge of, and often a deep connection to, patients affected physicians in various ways. Most of these effects were rewarding: feelings of connection, trust, curiosity, enhanced professional competence (diagnostically and therapeutically), personal growth, and being cared for and respected. Some, however, were distressing: anxiety, grief, frustration, boundary issues, and negative effects on personal life.

Conclusion

Family physicians experience myriad emotions connected with providing care to patients. Knowledge of what physicians find rewarding from their long-term connections with patients, and of the difficulties that arise, might be useful in further understanding interpersonal continuity of care and the therapeutic relationship, and in informing resident education about developing therapeutic relationships, evaluating resident educational experiences with continuity of care, and addressing physician burnout.

Résumé

Objectif

Déterminer ce que les médecins de famille en pratique traditionnelle, les médecins formés en médecine familiale œuvrant dans les soins épisodiques et les résidents en médecine familiale pensent de la continuité des soins afin de mieux comprendre les effets d’ordre émotionnel que subit le médecin qui établit une relation à long terme avec ses patients, comme point de départ pour l’élaboration d’un outil permettant de mesurer la relation qualitative entre le médecin et son patient.

Type d’étude

Étude qualitative descriptive à l’aide de groupes de discussion.

Contexte

Clinique familiale traditionnelle, programme de résidence en médecine familiale et contextes de soins épisodiques à Kingston, Ontario.

Participants

Trois groupes de résidents de première année du programme de médecine familiale (n = 18), 2 groupes de médecins de famille dans des cliniques traditionnelles bien établies (n = 9) et 2 groupes de médecins de famille travaillant dans des contextes de soins épisodiques (n = 10).

Méthodes

À l’aide de groupes de discussion, d’un guide de discussion semi-structuré et d’une approche phénoménologique, nous avons examiné l’idée que se font les résidents et les médecins en pratique de la continuité des soins, en insistant sur les effets émotionnels qu’éprouvent les médecins qui assurent le suivi d’un groupe de patients.

Principales observations

Le fait de traiter des patients pendant un certain temps, et de développer une profonde connaissance et souvent un lien significatif avec ceux-ci, avait divers effets sur les médecins. La plupart de ces effets étaient gratifiants : sentiment de liaison, de confiance, de curiosité, de compétence professionnelle accrue (pour le diagnostic et le traitement), de croissance personnelle, et d’être bien traité et respecté. Certains effets, par contre, étaient négatifs : anxiété, peine, frustration, connaissances insuffisantes et effets négatifs sur la vie privée.

Conclusion

Les médecins de famille éprouvent de nombreuses émotions en rapport avec les soins qu’ils prodiguent aux patients. Connaître ce que les médecins trouvent gratifiant et les difficultés qu’ils rencontrent dans leur relation à long terme avec les patients pourrait permettre de mieux comprendre la continuité interpersonnelle des soins et la relation thérapeutique, mais aussi de signaler l’importance pour le programme de formation de traiter de la relation thérapeutique, d’évaluer ce que les résidents apprennent sur la continuité des soins et de traiter de l’épuisement professionnel chez les médecins.

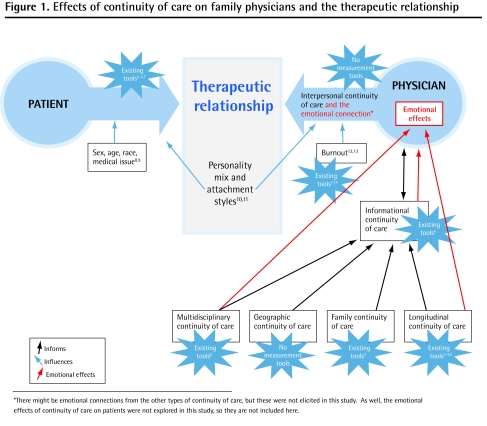

After developing a new continuity-of-care learning experience for family medicine residents at our institution, we wanted to measure its effectiveness in facilitating residents’ experiences with continuity of care. Continuity of care is not a single construct,1 but consists of various elements including longitudinal, family, geographic, multidisciplinary, informational, and interpersonal continuity of care (Table 1).2–6 Depending on the field or area of medicine studied, each of these is valued more or less.1,3,6 In family medicine, continuity of care has been described as a hierarchy, with interpersonal continuity of care identified as the key component and other aspects of continuity of care being necessary for its development.2 Evaluation of any family medicine learning experience with continuity of care therefore needs to measure appreciation of interpersonal continuity of care. Tools capturing the quantitative aspects of continuity of care exist (Table 1 and Figure 1),2–14 but no tools exist that capture the qualitative aspects of the interaction between physicians and patients. This has been identified as an important gap.2,4

Table 1.

Types of continuity of care and tools for measurement

| TYPE OF CONTINUITY OF CARE | DESCRIPTION | INFORMATION ACQUIRED OR CONNECTION ESTABLISHED THROUGH ... | EXAMPLES OF MEASUREMENT TOOLS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Interpersonal or relational | Enduring emotional connection of the physician to the patient | Caring for a patient over time, in situations that allow a unique body of knowledge about that patient to build and an emotional link to the patient to be established | Patient satisfaction surveys capture the connection of patient to physician2–5; no tool exists to capture the connection of physician to patient |

| Longitudinal | Care provided to a patient over time | Build-up of knowledge over time; seeing how the patient changes and the effects of care over time; familiarity | Duration of patient-provider affiliation (no. of visits from initial to final encounter); intensity of patient-provider affiliation (no. of visits in a defined interval); COC (no. of providers per patient); UPC (no. of visits in a given period compared with total no. of visits); COC Index (measures no. of different providers seen); K Index (known provider continuity; measures COC with different providers)2–4,6 |

| Geographic | Care provided to a patient in different settings (eg, office, hospital, home) | Seeing the environment patients establish for themselves; attending to and discussing personal mementos (eg, pictures, photographs) | No tool |

| Interdisciplinary | Care provided across disciplines (ie, 1 doctor providing different types of care) or coordination of care by 1 caregiver (ie, overseeing care of different specialists for the patient) | Putting together disparate pieces of information from many sources | Evidence of indicated follow-up for particular problems6 |

| Informational | Availability of patient’s past information | Connection builds as knowledge about the patient becomes more personalized | Evidence of information transfer (compare patient surveys with medical record)6 |

| Family | Care provided by 1 caregiver to different members of a family | Learning about patients in the unique context only family members can describe; understanding patients further through seeing how they assume different roles in the family | Proportion of immediate family members cared for by 1 provider; family Continuity of Care Index2 |

COC—concentration of care, UPC—usual provider of care.

Figure 1.

Effects of continuity of care on family physicians and the therapeutic relationship

Research about the effects on family physicians of interpersonal continuity of care is scant. Developing a sense of responsibility for patients and enhanced job satisfaction have been described,15 but many family doctors in traditional practice describe richer, more varied emotions than these. A British study16 explored these emotions more fully, also describing an increased sense of professional competence and challenges of worrying about making assumptions, delaying or missing diagnoses, overly dependent patients, and negative effects on personal life. In this project we asked what the emotional effects of continuity of care on family physicians were, with the intent to confirm and understand these emotions more fully and lay the groundwork for developing a tool to evaluate resident educational experiences with continuity of care. This could then be used with existing quantitative tools to fully assess all aspects of learning experiences with continuity of care.

METHODS

Using focus groups, a semistructured discussion guide, and a phenomenologic approach,17 we explored residents’ and practising physicians’ conceptions about continuity of care, predominantly exploring the emotional effects on physicians of providing care for a group of patients over time. Focus groups provide the opportunity for group interaction to explore ideas, raise questions, share anecdotes, and comment on one another’s experiences and points of view, which can possibly lead to a deeper exploration of concepts.18

Setting and participants

Three cohorts of physicians with varying exposure to long-term doctor-patient relationships were included in order to capture diverse knowledge, experiences, and opinions: residents, of course, had the least experience; family physicians in long-standing practices and in episodic-care settings were included to contrast long-term with short-term relationships.

Residents

All first-year family medicine residents from Queen’s University finishing their 16-week family medicine blocks at the time of the study (during which each worked in a single clinic following a preceptor’s patients) were invited.

Family physicians in long-standing practice

Family physicians with long-standing practices were purposively sampled to ensure a mix of age and sex, and academic, community, urban (population 120 000), and rural physicians, including some providing in-hospital care, primarily obstetrics. Two of the participants provided intrapartum care, and most did housecalls and provided nursing home care. Most worked in group practices.

Family physicians in episodic care

A convenience sample of family physicians working primarily in emergency departments was used.

Participants were sent a single e-mail invitation to participate. Focus groups with the episodic-care physicians took place at a local hospital after a regular meeting, and the other focus groups occurred at the Queen’s Family Medicine Centre. The Queen’s University Research Ethics Board granted ethics approval.

Discussion guide and data collection

The discussion guide was developed, after a review of the literature, through consensus among the research team on items that would explore interpersonal relationships. The guide comprised the following questions:

What does continuity of care mean to you?

How would you describe the emotional aspects of providing care to a group of patients over time?

What are some of the difficult aspects of doing that?

What are some of the rewarding aspects?

What promotes continuity of care?

What are the barriers?

The research assistant explained the study, obtained informed consent for participation and audiotaping, and, using the guide, led the semistructured discussion. The researchers did not participate in the focus groups.

Focus groups were conducted until no new information or ideas were emerging from the discussions. This occurred after 7 focus groups. A meal and a $200 honorarium was provided to each participant.

Data analysis

The recorded focus group discussions were transcribed and verified by the research assistant. Using a phenomenologic approach, 2 of the researchers (J.K. and K.S.) independently reviewed the transcripts to identify common themes and preliminary codes. The codes were refined and tested iteratively until themes and patterns emerged. Discrepancies were discussed and consensus was reached. The third researcher (D.D.) then reviewed the transcripts and analysis and independently confirmed the final results. NVivo 2.0 was used for systematic data analysis and to identify key quotations reflecting the themes.

FINDINGS

Seven 1-hour focus groups (2 with physicians in longstanding practice, 3 with residents, and 2 with physicians in episodic care) of 4 to 7 participants each were held between May 2007 and February 2009 (Table 2). Various themes within interpersonal continuity of care were identified, each with distressing and rewarding components.

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics of focus group participants

| CHARACTERISTICS | RESIDENTS (N = 18) | TRADITIONAL FAMILY PRACTICE (N = 9) | EPISODIC CARE (N = 10) | TOTALS (N = 37*) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | ||||

| • 20–29 | 14 | 0 | 0 | 14 |

| • 30–39 | 4 | 0 | 6 | 10 |

| • 40–49 | 0 | 4 | 3 | 7 |

| • 50–59 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 5 |

| • ≥ 60 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Sex | ||||

| • Male | 6 | 3 | 4 | 13 |

| • Female | 12 | 6 | 6 | 24 |

| Years in practice | ||||

| • 0 | 18 | 18 | ||

| • 1–5 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| • 6–10 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 5 |

| • >10 | 0 | 8 | 5 | 13 |

| Practice setting | ||||

| • Rural | NA | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| • Small city | NA | 0 | 10 | 10 |

| • City | NA | 6 | 0 | 6 |

NA—not applicable.

For practice setting n = 19, as this characteristic was not assessed for residents.

Familiarity or deep understanding of the patient

Rewarding

Physicians identified that a deep understanding of their patients resulted in more efficient and effective care, which led to an enhanced sense of professional competence. This was the result of an existing working knowledge of their patients, ability to interpret their patients’ nonverbal cues, and the ability to prioritize problems and provide personalized care. Improved care was also thought to occur because of an increased ability to use transference both diagnostically and therapeutically. Most thought the long-standing relationship could withstand addressing difficult issues, although some raised the concern that they might steer away from some sensitive issues for fear of upsetting patients. Knowing the patient well allowed the physician to predict how he or she might react in a particular situation, decreasing the anxiety related to gauging or anticipating those reactions. As one physician noted, “You have a thousand pieces of a puzzle; you start off with a 25-piece puzzle, but as the relationship grows and grows you get more and more pieces to clarify things more and more.” (FP*)

Distressing

Some physicians expressed anxiety caused by patients expecting them to recall a lot of details from memory. They also expressed a fear of complacency and missing diagnoses because of developing preconceived notions about their patients: “It makes me nervous at times because you get too comfortable.” (EP)

Connection to the patient

Rewarding

Feeling connected to their patients satisfied physicians’ desire for connection. They described interest in their patients’ lives and derived pleasure from good outcomes in both medical and nonmedical aspects of their patients’ lives. They often felt cared for by their patients and thought their patients were more tolerant of mistakes they might make: “You are touched in a way—not love, obviously, but very strong feelings of warmth and compassion.” (R)

Distressing

This deep connection to patients had its downsides. Physicians described a loss of anonymity. They experienced sadness and grief over poor outcomes in their patients’ lives. Although some patients were caring toward their physicians, some seemed more demanding and expected special treatment if they felt strongly connected to their physicians. For some there was “a sense of ownership from [patients] who feel you are their physician and therefore you should have to be at [their] beck and call.” (R) This raised boundary issues. Physicians worried about a loss of objectivity in the face of a strong connection to patients. They worried that if they felt strongly connected to and “went the extra mile” for patients that it would have negative effects on their personal lives.

Patients’ trust in the physician

Physicians described the trust patients developed in them through the in-depth knowledge gained and the connections made. Positively, this resulted in patients being more likely to disclose personal information that could assist in diagnosis and management. In addition, the trusting relationship and knowledge of patients’ fears allowed physicians to use the relationship therapeutically and led to adherence with treatment suggestions: “I think the relationship sometimes is a treatment.” (R) Adversely (as a result of creating extra appointments for the health care system), this could lead to patients requiring reassurance before embarking on a treatment advised by another physician and dependency of the patient on the physician.

Responsibility

Feeling in charge of patients’ care ranged from being rewarding (“I like running the show” [R]) to being anxiety-provoking and exhausting (“It can be exhausting … you can feel as if you have the weight of the world on your shoulders” [FP]).

Difficult patients

Distressing

Difficult patients could cause distressing feelings of anticipatory anxiety and, at times, fear: “[Y]ou see their name in your schedule and you say, ‘Oh God, I don’t want to see them again.’” (R) More time and effort was required to forge working relationships with these patients. If this was not successful and patients could not switch doctors, this could lead to feelings of frustration and, sometimes, anger.

Rewarding

Paradoxically, difficult patients could also engender rewarding emotions, particularly for the traditional family physicians. Physicians described satisfaction from understanding challenging patients and thereby developing a tolerance for their behaviour and forging good therapeutic relationships with them: “I don’t really have any heartsink patients because you’ve kind of figured them out.” (FP) They appreciated the personal growth they experienced through exploring their own values and the emotions evoked through caring for these patients.

Other types of continuity

In addition to interpersonal continuity of care, 2 other types of continuity of care, with their attendant rewarding and distressing aspects, were discussed.

Longitudinal continuity of care

As with deep knowledge of their patients, care over time improved physicians’ diagnostic and therapeutic abilities and enhanced their sense of professional competence. It afforded them the ability to see trends and diagnose slowly evolving conditions and gave them an increased ability to tie presentations together. They thought that patients were more likely to be compliant because there was no “hiding” from their physicians. Because of their interest in patients’ long-term health outcomes and because they knew they would be the ones subsequently seeing the patients, they thought they were less likely to use temporizing treatments and more likely to provide preventive care. They would use time as a diagnostic and therapeutic tool, as they could follow patients, could trust them to return, and were aware that some conditions take time to evolve. As one participant noted, “You’ll only see a change in that person if you see them for a very long time.” (FP) They thought this likely resulted in less need for consultations, tests, and medication. They believed themselves to be in a better position to implement and see the benefits of long-term plans, especially lifestyle changes and chronic disease management. Their sense of professional competence increased as they saw the positive outcomes of their management strategies. They described pleasure in seeing their patients grow and evolve on a personal level over time.

Longitudinal continuity of care for complex patients, however, could lead to less preventive care, particularly if the focus was on chronic disease management. It also could lead to frustration or apathy if patients were unable or unwilling to follow advice. Residents were particularly concerned about this frustration. There could be a decreased sense of competence if treatment strategies were not working:

I guess that I can get frustrated as well because while sometimes you see that things you are doing are working well, you can also see that all the various things that you are trying are doing absolutely nothing.

(R)

Interdisciplinary care

This aspect of continuity of care afforded physicians increased variety and intellectual stimulation:

[Y]ou might be delivering a baby, or you might be bringing [a patient] in for a biopsy or doing [cognitive behavioural therapy] .... In some situations people would be seeing a variety of care providers for all these different things and you can provide them all to the patient.

(FP)

However, particularly for residents, the interdisciplinary aspects of continuity could also at times create a feeling of an overwhelming amount of knowledge needed, causing anxiety and a sense of ineptitude:

I think it is very overwhelming because you are not in a specialty, so your amount of knowledge that you feel you need to uphold, and people expect you to uphold, is much larger than if you are in a specialty … and more pressure is added.

(R)

Differences between groups

The traditional family physicians described the importance of long-term relationships as a core value in their practices:

[W]ith continuity you really become part of the patient’s life; you’re not just somebody that they’re coming to consult, but you’re really a player—in the money—and that’s when the relationship, both ways, is very rewarding.

(FP)

This differed from the importance placed on informational continuity by the emergency physicians, who spoke of valuing the limits shift work placed on their responsibilities: “A lot of people [work in the emergency department] to not have continuity of care. There is a great relief in not having responsibility for long-term follow-up.” (EP)

While traditional family physicians focused on the rewards of establishing effective therapeutic relationships with difficult patients, residents were most likely to discuss the distressing challenges of difficult clinician-patient interactions:

[O]ne other downside of continuity of care is when you have a patient you do not like—you know, the one who makes you feel uncomfortable or something every time you are looking after them, and you see them anyway—you just dread them coming in.

(R)

DISCUSSION

The findings from this study further our understanding of the effects of continuity of care on family physicians. They support and add to the literature from other countries,16,19 suggesting that the dynamics of the long-standing family physician–patient relationship transcend national boundaries. The previously postulated concept of continuity of care as a unidirectional hierarchy2 is redefined by this study (Figure 1).2–14 Within the physician, the emotional effect of continuity of care appears to result from the unique information built up about individual patients through longitudinal, multidisciplinary, family, and geographic continuity, with longitudinal and multidisciplinary continuity also having independent emotional effects on the physician. Emotional effect is an important base for the emotional connection to the patient, which we propose underlies interpersonal continuity of care. This study also illustrates that emotional effects feed back into information about the patient if the physician attends to them.

What is the connection for family physicians between different types of continuity of care and the therapeutic relationship? We propose that interpersonal continuity of care differs from the therapeutic relationship (Figure 1).2–14 It is a state contained within the physician that results from caring for and coming to uniquely understand a patient, whereas the therapeutic relationship is the state that exists between physician and patient. Other factors can contribute to what each brings to this therapeutic relationship. For physicians, attachment style10,11 and burnout12,13 might moderate the emotional connection and thus affect the therapeutic relationship. Teasing out the distinction between the therapeutic relationship and interpersonal continuity of care opens up new areas of research. Two potential applications of these findings are evaluation of the teaching of continuity of care in family medicine residency programs and furthering our understanding of how to develop resilience and prevent burnout.

Having asked focus group participants to reflect on the effects of long-term relationships with patients, and taking into consideration the differences between the 3 different physician groups (discussed in more detail in a companion article20), we postulate that the emotions described by physicians in this study can be considered markers of interpersonal continuity of care for physicians. Using these as markers, the missing tool could be developed for capturing the quality of the doctor-patient relationship and assessing if a resident has understood both the positive and distressing aspects of long-term relationships with patients. If found to be valid, reliable, and sensitive, this tool, in conjunction with the existing quantitative tools2,6 and the effects from the patient’s perspective, could be used to assess continuity-of-care learning experiences.

Literature on job satisfaction and prevention of burnout points to the importance of positive interactions with patients.21,22 Understanding the rewarding and distressing aspects of interpersonal relationships with patients that are identified by this study and putting in place strategies to enhance the former and minimize the latter (eg, time to explore nonmedical aspects of patients’ lives, care to ensure contact with patients is not diluted as health care teams are put in place,23 skills to deal with difficult patients) could help to enhance job satisfaction.

Strengths and limitations

Most studies of continuity of care focus on patient satisfaction, with few dealing with physician perspectives. This study explores the effect of continuity of care on family physicians with various levels of experience.

This study was conducted in a single primary care setting with a limited number of participants. The access to care and patterns of practice might not reflect the situation in other jurisdictions. Focus groups might have inhibited some members from expressing opinions. Despite these limitations, the participants in this study had a range of views and opinions about continuity of care. Although the researchers did not conduct the focus groups, their backgrounds—one author (J.K.) was a second-year family medicine resident at the time of the study and the others are academic family physicians with more than 20 years in practice—might have influenced the interpretations. Careful review of transcripts for supporting and disconfirming themes and independent analysis minimized this risk.

Conclusion

Providing care for patients over time and developing a deep knowledge of, and often a deep connection to, patients affected physicians both positively (feelings of connection, trust, curiosity, enhanced diagnostic and therapeutic professional competence, personal growth, and a feeling of being cared for and respected) and negatively (anxiety, grief, frustration, boundary issues, and negative effects on personal life). This information might be useful in further understanding interpersonal continuity of care and the therapeutic relationship, evaluating resident educational experiences with continuity of care, informing resident education about developing therapeutic relationships, and adding to the literature on job satisfaction.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jane Yealland for running the focus groups. Financial assistance was received from the Physicians’ Services Incorporated Foundation through a Resident Research Grant.

EDITOR’S KEY POINTS

Research about the effects of interpersonal continuity of care on family physicians is scant and no tools exist to measure the qualitative connections between physicians and their patients.

The authors wanted to understand the emotional effects of continuity of care on family physicians in order to lay the groundwork for developing a tool to evaluate resident educational experiences with continuity of care. This could then be used with existing quantitative tools to fully assess all aspects of learning experiences with continuity of care.

Providing care for patients over time and developing a deep knowledge of—and often a deep connection to—patients affected physicians both positively and negatively. Residents were more likely to describe negative effects of continuity of care than physicians in long-standing practice were.

POINTS DE REPÈRE DU RÉDACTEUR

Peu d’études ont porté sur les effets de la continuité des soins interpersonnels sur le médecin de famille et il n’existe pas d’outil pour mesurer la qualité des liens entre le médecin et ses patients.

Les auteurs voulaient comprendre l’impact émotionnel de la continuité des soins sur le médecin de famille, de façon à poser les bases pour mettre au point un outil permettant d’évaluer ce que les résidents ont reçu comme enseignement sur la continuité des soins. Cela pourrait alors être utilisé conjointement avec les outils quantitatifs existants pour évaluer tous les aspects de ce que les résidents apprennent de la continuité des soins.

Le fait de traiter des patients pendant un certain temps et de développer une meilleure connaissance - et souvent des liens plus profonds - avec ceux-ci avait des effets tant positifs que négatifs sur le médecin. Les résidents étaient plus susceptibles de rapporter des effets négatifs de la continuité des soins que les médecins de famille pratiquant depuis longtemps.

Footnotes

Quotations are identified as coming from family physicians in long-standing practice (FP), episodic-care physicians with family medicine training (EP), or residents (R).

This article has been peer reviewed.

This article is eligible for Mainpro-M1 credits.

To earn credits, go to www.cfp.ca and click on the Mainpro link.

Cet article a fait l’objet d’une révision par des pairs.

Competing interests

None declared

Contributors

All authors contributed to the concept and design of the study; data gathering, analysis, and interpretation; and preparing the manuscript for submission.

References

- 1.Haggerty JL, Reid RJ, Freeman GK, Starfield BH, Adair CE, McKendry R. Continuity of care: a multidisciplinary review. BMJ. 2003;327(7425):1219–21. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7425.1219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saultz JW. Defining and measuring continuity of care. Ann Fam Med. 2003;1(3):134–43. doi: 10.1370/afm.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Starfield B. Primary care: balancing health needs, services, and technology. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jee SH, Cabana MD. Indices for continuity of care: a systematic review of the literature. Med Care Res Rev. 2006;63(2):158–88. doi: 10.1177/1077558705285294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stewart M, Brown JB, Weston WW, McWhinney IR, McWilliam CL, Freeman TR. Patient-centered medicine. Transforming the clinical method. 2nd ed. Abingdon, UK: Radcliffe Medical Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reid R, Haggerty J, McKendry R. Defusing the confusion: concepts and measures of continuity of healthcare. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Health Services Research Foundation; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stress Management from Mind Tools [website] Burnout Self-Test—stress management techniques from Mind Tools. Mind Tools Inc; 1996. Available from: www.mindtools.com/stress/Brn/BurnoutSelfTest.htm. Accessed 2011 Dec 8. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kearley KE, Freeman GK, Heath A. An exploration of the value of the personal doctor-patient relationship in general practice. Br J Gen Pract. 2001;51(470):712–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pereira AG, Pearson SD. Patient attitudes toward continuity of care. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(8):909–12. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.8.909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ciechanowski PS, Russo JE, Kabon WJ, Walker EA. Attachment theory in health care: the influence of relationship style on medical student’s specialty choice. Med Educ. 2004;38(3):262–70. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2004.01767.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Adshead G. Becoming a caregiver: attachment theory and poorly performing doctors. Med Educ. 2010;44(2):125–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03556.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Visser MR, Smetz EM, Oort FJ, De Haes HC. Stress, satisfaction and burn-out among Dutch medical specialists. CMAJ. 2003;168(3):271–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leiter MP, Frank E, Matheson TJ. Demands, values and burnout. Relevance for physicians. Can Fam Physician. 2009;55:1224–5. e1–6. Available from: www.cfp.ca/content/55/12/1224.full.pdf+html. Accessed 2011 Dec 8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maslach C, Jackson SE. The measurement of experienced burnout. J Organ Behav. 1981;2(2):99–113. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saultz JW, Albedaiwi W. Interpersonal continuity of care and patient satisfaction: a critical review. Ann Fam Med. 2004;2(5):445–51. doi: 10.1370/afm.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ridd M, Shaw A, Salisbury C. “Two sides of the coin”—the value of personal continuity to GPs: a qualitative interview study. Fam Pract. 2006;23(4):461–8. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cml010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reeves S, Albert M, Kuper A, Hodges BD. Why use theories in qualitative research? BMJ. 2008;337:a949. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kitzinger J. Qualitative research. Introducing focus groups. BMJ. 1995;311(7000):299–302. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.7000.299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stokes T, Tarrant C, Mainous AG, 3rd, Schers H, Freeman G, Baker R. Continuity of care: is the personal doctor still important? A survey of general practitioners and family physicians in England and Wales, the United States, and the Netherlands. Ann Fam Med. 2005;3(4):353–9. doi: 10.1370/afm.351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Delva D, Kerr J, Schultz K. Continuity of care. Differing conceptions and values. Can Fam Physician. 2011;57:915–21. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Daghio MM, Ciardullo AV, Cadioli T, Delvecchio C, Menna A, Voci A, et al. GP’s satisfaction with the doctor-patient encounter: findings from a community-based survey. Fam Pract. 2003;30(3):283–8. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmg309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee FJ, Stewart M, Brown JB. Stress, burnout, and strategies for reducing them: what’s the situation among Canadian family physicians? Can Fam Physician. 2008;54:234–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wagner EH, Reid RR. Are continuity of care and teamwork incompatible? Med Care. 2007;45(1):6–7. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000253165.03466.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]