Abstract

Background

Chronic low back pain is a common problem lacking highly effective treatment options. Small trials suggest that yoga may have benefits for this condition. This trial was designed to determine whether yoga is more effective than conventional stretching exercises or a self-care book for primary care patients with chronic low back pain.

Methods

228 adults with chronic low back pain were randomized to 12 weekly classes of yoga (n=92) or conventional stretching exercises (n=91) or a self-care book (n=45). Back-related functional status (modified Roland Disability Questionnaire, 23-point scale) and bothersomeness of pain (11-point numerical scale) at 12 weeks were the primary outcomes. Outcomes were assessed at baseline, 6, 12 and 26 weeks by interviewers unaware of treatment group.

Results

After adjustment for baseline values, 12-week outcomes for the yoga group were superior to those for the self-care group (mean difference for function = −2.5 [95% CI= −3.7 to −1.3; P<0.001]; mean difference for symptoms = −1.1 [95% CI= −1.7 to −0.4; P<0.001]). At 26 weeks, function for the yoga group remained superior (mean difference = −1.8 [95% CI= − 3.1 to −0.5; P<0.0001]). Yoga was not superior to conventional stretching exercises at any time point.

Conclusions

Yoga classes were more effective than a self-care book, but not stretching classes, in improving function and reducing symptoms due to chronic low back pain, with benefits lasting at least several months.

Despite the availability of numerous treatments for chronic back pain, none have proven highly effective and few have been evaluated for cost-effectiveness.1 Self-management strategies, like exercise, are particularly appealing because they are relatively safe, inexpensive, and accessible and may have beneficial effects on health beyond those for back pain.

One form of exercise with at least “fair” evidence for effectiveness for back pain is yoga.2 Yoga might be an especially promising form of exercise because it includes a mental component could enhance the benefits of its physical components. Although all studies of yoga for back pain we could identify found yoga effective,3–9 most had significant limitations including small sample sizes. Our own preliminary trial found yoga slightly more effective than a comprehensive program including aerobic, strengthening and stretching exercises and more effective than a self-care book.5 The current trial compares the effectiveness of yoga classes to stretching classes of comparable physical exertion, and to self-care for chronic non-specific low back pain. We hypothesized that yoga would be superior to both comparison groups.

METHODS

Design Overview

We conducted a 3-arm parallel group stratified controlled trial, allocating participants in a 2:2:1 ratio to yoga, stretching exercises, and self-care, respectively. Trial protocol and procedures were approved by the Group Health institutional review board. Participants gave oral informed consent before telephone eligibility screening. Those remaining eligible provided written informed consent prior to an in-person physical examination and study enrollment. The detailed trial protocol has been published previously10 and is briefly summarized herein.

Setting and Participants

Participants were recruited from Group Health, an integrated health care organization, and from the general population in the Puget Sound area. Seven cohorts of classes were conducted in six cities in Western Washington between June 2007 and May 2009. Recruitment methods included mailed invitations to Group Health members with back pain visits to primary care providers, advertisements in the health plan’s magazine, and direct-mail postcards. For four cohorts, we augmented these with outreach to the general population. The study was described as a comparison of three different approaches designed to decrease the negative effects of back pain on participants’ lives.

We excluded persons whose back pain was attributed to a specific cause (e.g., spondylolisthesis, or fractured vertebra), potentially due to an underlying medical condition (e.g., metastatic cancer, pregnancy), complex (e.g., sciatica, spinal stenosis, medicolegal issues or a previous back surgery), minimally painful at time of screening (less than 3 on a 11-point “bothersomeness” scale of 0 to 10), or not chronic (i.e., had lasted less than 3 months). We also excluded persons with medical conditions for which yoga or exercise were contraindicated (e.g., severe disc disease), with major depression, with inability to give informed consent or participate in our interviews due to mental or medical issues (e.g., dementia) or inability to speak English. Finally, we excluded persons who were unable to attend classes or unwilling to do home practice.

Randomization

After completing the baseline interview at Group Health facilities, participants within each recruitment cohort were randomized by a research assistant to the three treatment arms in a ratio of 2:2:1 (Yoga: Stretching: Self-Care). Treatment assignments were generated by a statistician (AJC) using R version 2.1011 with random block sizes of 5 or 10, which were then embedded in the computer-assisted telephone interviewing program by a programmer (KD) to be inaccessible by study staff prior to randomization.

Interventions

A series of 12 standardized weekly 75-minute yoga and stretching classes, held in Group Health facilities, designed for people with chronic low back pain unaccustomed to yoga or stretching. Participants were asked to practice 20 minutes on non-class days and were given handouts and CDs (yoga) or DVDs (stretching) to assist in this. All participants continued to have access to medical care covered by their insurance plan. One researcher (KJS) attended one class for each intervention for each cohort to evaluate adherence to the protocols.

Yoga

The yoga classes used the same protocol employed in our earlier trial5, developed using the principles of viniyoga and included 17 relatively simple postures, with variations and adaptations. Each class included breathing exercises, 5 to 11 postures (lasting approximately 45–50 minutes), and guided deep relaxation. Six distinct and progressive classes were taught in pairs. Classes were taught by instructors with at least 500 hours of viniyoga training, five years teaching experience, familiarity with the selected postures and who were briefed by our yoga consultant.

Stretching

The stretching classes were adapted from our previous trial5, which included aerobic exercises, 10 strengthening exercises and 12 stretches, held for 30 seconds each (total of 10.5 minutes of stretching). Classes consisted of 15 exercises designed to stretch the major muscle groups but emphasizing the trunk and legs (total of 52 minutes of stretching), and four strengthening exercises. Classes were led by licensed physical therapists who had previous experience leading classes and had completed a two hour teacher training program.

Self-care Book

Self-care participants received The Back Pain Helpbook,12 which provides information on the causes of back pain and advice on exercising, making appropriate life-style modifications and managing flare-ups.

Outcomes and Follow-up

Telephone interviews were conducted by masked interviewers at baseline, and at 6, 12, and 26-weeks post-randomization. Before randomization, information on sociodemographic characteristics, back pain history, and treatment-related beliefs was collected. Primary outcomes, were the validated 23-item Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire (RDQ)13 and self-rated symptom bothersomeness on a 0 to 10 scale.14 The 12-week follow-up was considered the primary end point. Secondary outcomes included activity restriction,15 patient global rating of improvement and patient satisfaction.16 Data on adverse events were collected at all follow-up interviews by asking participants if they had experienced any serious health events and anything harmful from the interventions.

Statistical Analysis

Following the a priori primary analysis plan10, primary outcomes, RDQ and symptom bothersomeness, were analyzed using regression with generalized estimating equations (GEE),17 assuming an independent working correlation structure and using robust standard error estimation. Follow-up times and treatment levels were included as categorical variables and all two-way interactions between the two were present in each model. All adjusted models included baseline measures of RDQ and bothersomeness scores, gender, age, body mass index (BMI), days of lower back pain in the last six months, pain travelling down the leg and employment-related exertion. Sensitivity analyses further adjusting for class cohort did not change results (data not shown). Another sensitivity analysis found that results were not affected by the method of analysis (GEE vs linear mixed effects model).

Similar methods were used to analyze secondary outcomes with modification of the estimating equations for use with binary outcomes. To facilitate understanding and interpretation, we present relative risks between treatment arms for all secondary outcomes using a modified Poisson regression approach assuming Poisson model-based estimating equations with robust standard errors.18

To control for multiple comparisons, we evaluated pairwise treatment comparisons for each time point only if the overall omnibus test was statistically significant at the 0.05-level. Mean differences, 95% confidence intervals, omnibus p-values for the effect of treatment group and pairwise significance are presented. Adjusted means and 95% CIs are presented graphically at each follow-up time.

All analyses were conducted assuming intent-to-treat principles using SAS® software version 9.2.19 All P-values and confidence intervals are two-sided with statistical significance at the 0.05 level.

Loss to Follow-Up

Per the study protocol, we conducted a secondary analysis using a single imputation method of Wang and Fitzmaurice for situations where non-response may be non-ignorable20 to evaluate the sensitivity of the complete-case results to differential loss to follow-up between the treatment arms. Results of this analysis for the primary study outcomes, which confirm the main findings, are presented as an online appendix.

RESULTS

Participants

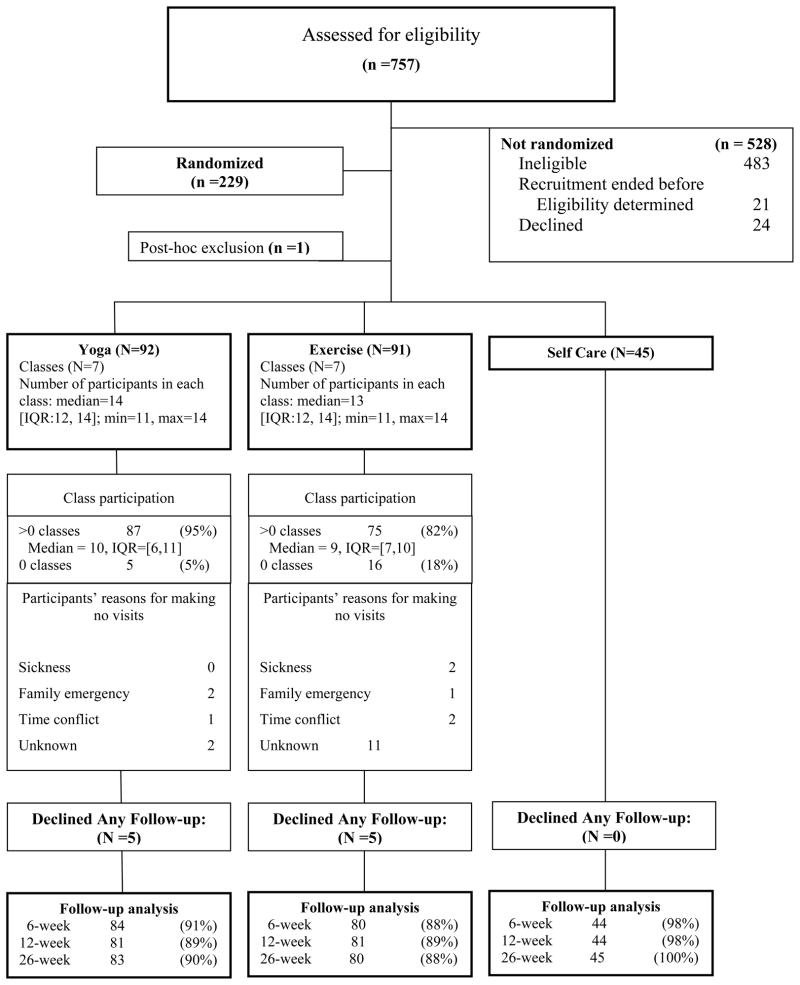

Of 757 individuals assessed for eligibility between March 2007 and March 2009, 229 were randomized, including 203 Group Health members (Figure 1). One inappropriately randomized individual, whose PHQ-9 score exceeded the eligibility threshold, was removed from the trial when the error was discovered after randomization but before classes began. Thus, 228 persons were included in the analyses (92 randomized to yoga, 91 to stretching, and 45 to self-care). Overall follow-up rates were 90 or 91% at all time points.

Figure 1.

Participant Flow Diagram

Baseline characteristics were well-balanced across groups, except the yoga group had greater back dysfunction (Table 1). 59% of participants were using medications at baseline, mostly non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications. Fewer than 12% of participants reported use of acetaminophen, muscle relaxants, opioids or anti-depressants.

Table 1.

Baseline description of study participants by treatment group

| Yoga | Stretching | Self-care | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TOTAL, N | 92 | 91 | 45 | 228 |

|

| ||||

| Demographics

| ||||

| Age, mean (SD), yrs | 46.6 (9.8) | 49 (9.91) | 50.8 (9.07) | 48.4 (9.79) |

|

| ||||

| Women, N (%) | 62 (67%) | 57 (63%) | 27 (60%) | 146 (64%) |

|

| ||||

| College graduate, N (%) | 54 (59%) | 59 (65%) | 28 (62%) | 141 (62%) |

|

| ||||

| White, N (%) | 80 (87%) | 76 (84%) | 43 (96%) | 199 (87%) |

|

| ||||

| Hispanic, N (%) | 2 (2%) | 3 (3%) | 2 (4%) | 7 (3%) |

|

| ||||

| Married, N (%) | 71 (77%) | 60 (66%) | 34 (76%) | 165 (72%) |

|

| ||||

| Family income > $45,000/yr, N (%) | 79 (87%) | 72 (83%) | 34 (80%) | 185 (84%) |

|

| ||||

| Employment, N (%)

| ||||

| None | 13 (14%) | 11 (12%) | 5 (11%) | 29 (13%) |

|

| ||||

| Lifts less than 20 lbs at job | 58 (64%) | 54 (60%) | 25 (56%) | 137 (61%) |

|

| ||||

| Lifts 20 lbs + at job | 20 (22%) | 25 (28%) | 15 (33%) | 60 (27%) |

|

| ||||

| Smoker, N (%) | 2 (2%) | 4 (4%) | 3 (7%) | 9 (4%) |

|

| ||||

| Obese (BMI>=30), N (%) | 26 (28%) | 28 (31%) | 15 (34%) | 69 (31%) |

|

| ||||

| MHI-5 score, mean (SD)

| ||||

| Mental health component | 45.6 (4.0) | 45.5 (4.3) | 45.3 (3.7) | 45.5 (4.0) |

|

| ||||

| Back Pain History

| ||||

| Began > 1 year ago, N (%) | 85 (92%) | 80 (89%) | 41 (91%) | 206 (91%) |

|

| ||||

| Lasted > 1 year, N (%) | 74 (81%) | 55 (63%) | 34 (76%) | 163 (73%) |

|

| ||||

| Years of low back pain, mean (SD) | 10.6 (10.6) | 11.1 (9.24) | 10.3 (10. 6) | 10.8 (10) |

|

| ||||

| Pain below knee, N (%) | 13 (14%) | 13 (14%) | 11 (24%) | 37 (16%) |

|

| ||||

| Days of back pain in last 6 months, mean (SD) | 147 (47.2) | 128 (53.5) | 143 (50.9) | 139 (51) |

|

| ||||

| > 7 days restricted activity due to LBP in the past month, N (%) | 24 (26%) | 19 (21%) | 14 (31%) | 57 (25%) |

|

| ||||

| > 1 Days in bed due to LBP in past month, % | 12 (13%) | 12 (13%) | 4 (9.0%) | 28 (12%) |

|

| ||||

| > 1 Day of work lost due to LBP in past month, N(%) | 8 (9%) | 8 (9%) | 3 (7%) | 19 (9%) |

|

| ||||

| Baseline Outcomes

| ||||

| Roland Disability Questionnaire (RDQ), mean (SD) | 9.8 (5.2) | 8.6 (4.0) | 9.0 (5.0) | 9.1 (4.7) |

|

| ||||

| Eligibility bothersomeness score, mean (SD) | 5.7 (1.7) | 5.4 (1.7) | 5.4 (1.8) | 5.5 (1.7) |

|

| ||||

| Baseline bothersomeness score, mean (SD) | 4.9 (1.9) | 4.5 (1.9) | 4.7 (2.5) | 4.7 (2.1) |

|

| ||||

| Pain Management

| ||||

| Hours of back exercise in past week, mean (SD) | 0.4 (0.6) | 0.3 (0.4) | 0.5 (0.5) | 0.3 (0.5) |

|

| ||||

| 3+ days of back exercise in past week, N (%) | 25 (27%) | 21 (23%) | 18 (41%) | 64 (28%) |

|

| ||||

| Hours of active exercise in past week, mean (SD) | 2.4 (3.3) | 2.4 (2.5) | 2.5 (2.5) | 2.4 (2.8) |

|

| ||||

| 3+ days of active exercise in past week, N (%) | 47 (51%) | 50 (55%) | 26 (58%) | 123 (54%) |

|

| ||||

| Medication, N (%)

| ||||

| Used any medication for LBP in past week, N(%) | 52 (57%) | 59 (65%) | 24 (53%) | 135 (59%) |

|

| ||||

| Used nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for back pain in past week, N(%) | 37 (40%) | 47 (52%) | 16 (36%) | 100 (44%) |

|

| ||||

| Used narcotic analgesics for back pain in past week, N (%) | 9 (10%) | 6 (7%) | 2 (4%) | 17 (7%) |

|

| ||||

| Injected medication, N (%) | 10 (11%) | 6 (7%) | 3 (7%) | 19 (8%) |

|

| ||||

| Very satisfied with overall care for LBP, N (%) | 15 (18%) | 17 (22%) | 8 (21%) | 40 (20%) |

|

| ||||

| Expectation of Helpfulness (11 point scale)

| ||||

| Yoga class, median | 8.0 | 8.0 | 8.0 | 8.0 |

| Exercise class, median | 8.0 | 8.0 | 8.0 | 8.0 |

| Self-care book, median | 4.0 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 4.0 |

|

| ||||

| Preferred Treatment

| ||||

| Yoga, N (%) | 24 (26%) | 29 (32%) | 12 (27%) | 65 (29%) |

| Exercise, N (%) | 19 (21%) | 15 (17%) | 10 (22%) | 44 (19%) |

| Other, N (%) | 49 (53%) | 47 (52%) | 23 (51%) | 119 (52%) |

|

| ||||

|

Prior Yoga Experience

| ||||

| Ever attended a yoga class, N (%) | 45 (49%) | 38 (42%) | 17 (38%) | 100 (44%) |

Abbreviations: LBP = Lower Back Pain; RDQ = Roland Disability Questionaire; SD = Standard Deviation; MHI = Mental Health Inventory.

Study Treatments

Participants randomized to yoga were more likely than those assigned to stretching to attend at least one class (95% versus 82%, respectively) (Figure 1). Attendance was more similar using two other measures of class adherence-- proportion attending at least 8 classes (65% for yoga and 59% for stretching) and proportion attending at least 3 of the first 6 and 3 of the last 6 classes (67% for yoga and 66% for stretching). The median number of classes attended among those attending at least one class was similar (10 versus 9).

Nine or more weekly home practice logs were completed by over 70% of class attendees. Sixty-three percent of yoga attendees versus 82% of stretching attendees reported home practice 3 or more days per week. At both 6- and 12-weeks, most participants reported practicing at home at least 3 days in the prior week. The median duration of weekly practice was 100 minutes at week 6 and 60 minutes at week 12 for the yoga group and 120 minutes at week 6 and 75 minutes at week 12 in the stretching group. By 26 weeks, 59% of the yoga group and 40% of the stretching group reported practicing at home at least 3 days in the prior week (median weekly practices of 35 and 30 minutes, respectively).

Participants in both classes rated median “connection” with their class instructor as 7, using a 0 (no connection) to 10 (extremely close connection) rating scale and rated median support from classmates at 5 on a similar scale. The percentage reporting they would definitely recommend the class to others was substantially higher in the yoga class (85% vs. 54%; RR=1.6 (95% CI = 1.1 to 2.3; p = 0.03).

Most self-care participants (86%) reported reading some of the book, with nearly half reading more than two-thirds.

Non-study Treatments

Compared to baseline, roughly a quarter to a third fewer participants in the yoga and stretching groups reported using any medications for back pain in the week prior to each interview. Medication use in the self-care group did not decrease until 26 weeks. Compared to self-care, twice as many participants in the yoga and stretching groups (roughly 40% vs. 20%) at the 12 and 26 week follow-up interviews reported decreasing their medication use since the previous interview.

Back pain-related visits to health care providers (mostly massage therapists and chiropractors) were reported by 30% of participants during the classes and 40% during the post-class follow-up period with no group differences.

Self-reported duration of active exercise in the week prior to interview was similar among the three groups at any follow-up period (P>0.50 for all comparisons).

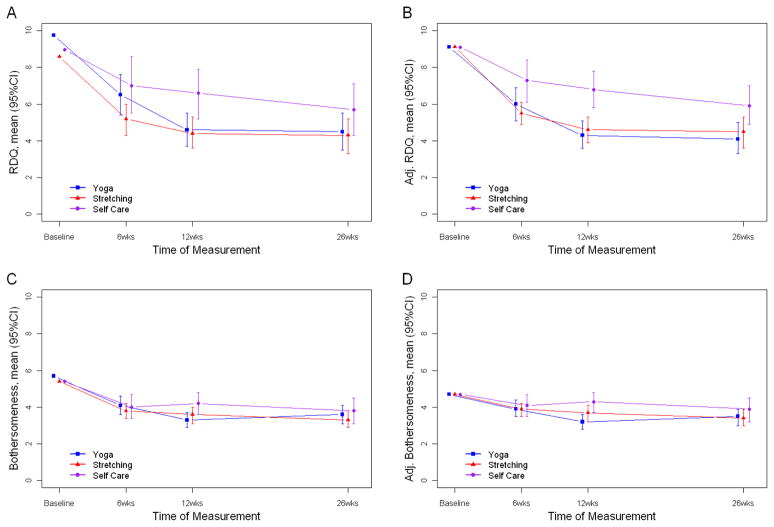

Back-related dysfunction and Symptoms

Back-related dysfunction (RDQ score) declined over time in all groups (Figure 1, Table 2), with significant differences in the adjusted analyses among the 3 groups at all follow-up interviews (6 weeks: P=0.04; 12 weeks: p<0.001; 26 weeks: p=0.026). Compared to self care, the yoga group reported superior function at 12 (mean difference [95%CI] = −2.5 [−3.7 to −1.3]) and 26 weeks (−1.8 [−3.1 to −1.5]) and the stretching group reported superior function at 6 (−1.7 [−3.0 to −0.4]), 12 (−2.2 [−3.4 to −1.0]), and 26 weeks (−1.5 [−2.8 to −0.2]) (Table 2). There were no statistically or clinically significant differences between the yoga and stretching groups.

Table 2.

Mean Estimates and 95% Confidence Intervals by Treatment Group and Mean Group Differences between groups

| Primary Outcomes estimate (95% CI) | Mean Estimates

|

Between-Group Differences

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yoga (Y) | Stretching (S) | Self-Care (SC) | Omnibus p-valuea | Yoga vs. Self Care | Stretching vs. Self Care | Yoga vs. Stretching | |

|

Unadjusted analysis

| |||||||

| RDQ | |||||||

| 6 weeks | 6.47 (5.37, 7.58) | 5.15 (4.33, 5.97) | 7.04 (5.49, 8.58) | 0.05 | −0.56 (−2.46, 1.34) | −1.88 (−3.63, −0.14) | 1.32 (−0.06, 2.70) |

| 12 weeks | 4.59 (3.66, 5.53) | 4.43 (3.60, 5.26) | 6.56 (5.17, 7.94) | 0.04 | −1.96 (−3.63, −0.29) | −2.12 (−3.74, −0.51) | 0.16 (−1.09, 1.41) |

| 26 weeks | 4.49 (3.51, 5.48) | 4.26 (3.30, 5.22) | 5.73 (4.33, 7.12) | 0.23 | -- | -- | -- |

| Bothersomeness | |||||||

| 6 weeks | 4.10 (3.63, 4.56) | 3.78 (3.38, 4.17) | 4.04 (3.43, 4.66) | 0.55 | -- | -- | -- |

| 12 weeks | 3.26 (2.85, 3.67) | 3.59 (3.14, 4.04) | 4.20 (3.61, 4.80) | 0.05 | −0.95 (−1.66, −0.23) | −0.61 (−1.36, 0.13) | −0.33 (−0.94, 0.27) |

| 26 weeks | 3.59 (3.12, 4.06) | 3.34 (2.86, 3.81) | 3.80 (3.14, 4.46) | 0.52 | -- | -- | -- |

|

| |||||||

|

Adjusted analysisb

| |||||||

| RDQ | |||||||

| 6 weeks | 6.02 (5.15, 6.89) | 5.51 (4.90, 6.13) | 7.26 (6.09, 8.43) | 0.04 | −1.24 (−2.70, 0.23) | −1.74 (−3.04, −0.44) | 0.50 (−0.57, 1.58) |

| 12 weeks | 4.31 (3.55, 5.08) | 4.61 (3.92, 5.30) | 6.79 (5.83, 7.76) | <0.001 | −2.48 (−3.70, −1.26) | −2.18 (−3.37, −1.00) | −0.30 (−1.33, 0.74) |

| 26 weeks | 4.12 (3.28, 4.97) | 4.47 (3.64, 5.30) | 5.93 (4.92, 6.95) | 0.03 | −1.81 (−3.12, −0.50) | −1.47 (−2.78, −0.17) | −0.35 (−1.52, 0.83) |

| Bothersomeness | |||||||

| 6 weeks | 3.95 (3.52, 4.38) | 3.87 (3.51, 4.24) | 4.09 (3.48, 4.71) | 0.83 | -- | -- | -- |

| 12 weeks | 3.18 (2.81, 3.56) | 3.67 (3.23, 4.12) | 4.26 (3.71, 4.81) | 0.01 | −1.07 (−1.75, −0.41) | −0.59 (−1.30, 0.11) | −0.49 (−1.06, 0.08) |

| 26 weeks | 3.48 (3.04, 3.92) | 3.42 (2.96, 3.87) | 3.85 (3.24, 4.46) | 0.51 | -- | -- | -- |

Abbreviations: RDQ = Roland Disability Questionnaire

Between Group Comparisons were only calculated if the omnibus p-value was <0.05 following the Least Significant Difference approach to control for multiple comparisons

Estimates adjusted for baseline RDQ and bothersomeness score, gender, age, BMI, days of lower back pain in the last six months, pain travelling down the leg and employment-related exertion.

Except at 12 weeks, there were no meaningful differences among the treatment groups for symptom bothersomeness (Figure 2). At 12 weeks, the yoga group was significantly less bothered by symptoms than the self-care group. (Table 2).

Figure 2.

Mean unadjusted (A and C) and adjusted (B and D) Roland Disability Questionnaire (RDQ) (A and B) and bothersomeness scores (C and D) at baseline, 6, 12, and 26 weeks by treatment group.

We explored two additional measures of clinical improvement: 30% improvement from baseline (representing minimal improvement)21 and 50% improvement from baseline (representing substantial improvement) (Table 3). Compared to self-care at 12 weeks, significantly more participants in both class groups improved by both criteria for both primary outcomes. For example, 52% to 56% of participants in the yoga and stretching groups improved by a least 50% on the RDQ compared with only 23% in the self-care group (P<0.0004). At 26 weeks, both yoga and stretching showed substantial benefits beyond self-care on the RDQ, while stretching showed substantial benefits on bothersomeness.

Table 3.

Secondary outcomes: mean estimates and relative risk for pairwise comparisons.

| Secondary outcome mean (95% CI) | Adjusted Mean Estimatesb |

Adjusted Relative Riska |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yoga (Y) | Stretching (S) | Self-Care (SC) | Omnibus p-valuea | Yoga vs. Self Care | Stretching vs. Self Care | Yoga vs. Stretching | |

|

Binary Variables

| |||||||

| RDQ 30% improvement | |||||||

| 6 weeks | 55% (46, 67) | 58% (48, 70) | 49% (37, 67) | 0.64 | -- | -- | -- |

| 12 weeks | 75% (66, 86) | 71% (63, 83) | 45% (32, 63) | 0.007 | 1.67 (1.17, 2.40) | 1.58 (1.10, 2.27) | 1.06 (0.87, 1.28) |

| 26 weeks | 66% (56, 78) | 72% (63, 83) | 55% (43, 72) | 0.18 | -- | -- | -- |

| RDQ 50% improvement | |||||||

| 6 weeks | 35% (26, 47) | 38% (29, 49) | 21% (12, 37) | 0.10 | -- | -- | -- |

| 12 weeks | 56% (46, 68) | 52% (41, 63) | 23% (14, 38) | <0.001 | 2.43 (1.40, 4.20) | 2.25 (1.29, 3.93) | 1.08 (0.81, 1.43) |

| 26 weeks | 60% (50, 72) | 51% (41, 63) | 31% (21, 48) | 0.007 | 1.90 (1.21, 2.99) | 1.63 (1.03, 2.59) | 1.17 (0.88, 1.54) |

| Bothersomeness 30% improvement | |||||||

| 6 weeks | 36% (27, 48) | 34% (26, 45) | 32% (23, 46) | 0.89 | -- | -- | -- |

| 12 weeks | 52% (42, 64) | 48% (38, 59) | 23% (15, 36) | <0.001 | 2.24 (1.36, 3.70) | 2.07 (1.26, 3.39) | 1.08 (0.80, 1.46) |

| 26 weeks | 52% (41, 64) | 44% (35, 56) | 29% (19, 43) | 0.03 | 1.80 (1.12, 2.84) | 1.52 (0.96, 2.43) | 1.72 (0.85, 1.62) |

| Bothersomeness 50% improvement | |||||||

| 6 weeks | 16% (10, 26) | 12% (7, 21) | 11% (6, 19) | 0.58 | -- | -- | -- |

| 12 weeks | 25% (17, 37) | 18% (12, 27) | 11% (6, 20) | 0.04 | 2.37 (1.14, 4.94) | 1.66 (0.78, 3.51) | 1.42 (0.81, 2.51) |

| 26 weeks | 22% (15, 34) | 29% (21, 39) | 11% (5, 21) | 0.01 | 2.13 (0.96, 4.73) | 2.73 (1.29, 5.78) | 0.78 (0.47, 1.31) |

| LBP better, much better or completely gone. | |||||||

| 6 weeks | 35% (26, 47) | 34% (26, 46) | 11% (5, 27) | 0.003 | 3.08 (1.26, 7.53) | 3.01 (1.24, 7.32) | 1.02 (0.67, 1.55) |

| 12 weeks | 60% (50, 72) | 46% (36, 58) | 16% (8, 31) | <0.001 | 3.78 (1.86, 7.66) | 2.90 (1.42, 5.93) | 1.3 (0.97, 1.75) |

| 26 weeks | 51% (42, 63) | 51% (41, 63) | 20% (11, 36) | <0.001 | 2.57 (1.39, 4.78) | 2.58 (1.39, 4.77) | 1 (0.75, 1.34) |

| Very satisfied with overall care for LBP | |||||||

| 6 weeks | 48% (39, 60) | 35% (26, 47) | 13% (6, 29) | <0.001 | 3.73 (1.62, 8.59) | 2.72 (1.16, 6.36) | 1.37 (0.96, 1.97) |

| 12 weeks | 60% (50, 73) | 42% (33, 55) | 15% (7, 31) | <0.001 | 3.95 (1.90, 8.21) | 2.77 (1.31, 5.89) | 1.42 (1.05, 1.93) |

Abbreviations: RDQ = Roland Disability Questionnaire; LBP = Lower Back Pain.

Between Group Comparisons (relative risks) were only calculated if the omnibus p-value was <0.05 following the Least Significant Difference approach to control for multiple comparisons.

Estimates adjusted for baseline RDQ and bothersomeness score, gender, age, BMI, days of lower back pain in the last six months, pain travelling down the leg and employment-related exertion.

Other Outcomes

At each follow-up interview, 2–6% of participants in the 3 groups reported 7 or more days of activity restrictions over the previous 4 weeks, 5–6% of participants reported any days in bed and 4–8% reported any work loss.

Compared to self-care, yoga and stretching participants were significantly more likely to rate their back pain as better, much better, or completely gone at all follow-up times (Table 3). More participants in the yoga and stretching groups were very satisfied with their overall care for back pain.

Adverse Events

Of the 87 yoga and 75 stretching class attendees, 13 in each group reported a mild or moderate adverse experience possibly related to treatment (mostly increased back pain) and 1 yoga attendee experienced a herniated disc. One of 45 persons randomized to self care reported increased pain after doing recommended exercises.

COMMENT

We found physical activity involving stretching, regardless of whether it is achieved using yoga or more conventional exercises, has moderate benefits in individuals with moderately impairing low back pain. Finding similar effects for both approaches suggests that yoga’s benefits were largely attributable to the physical benefits of stretching and strengthening the muscles and not to its mental components. Although the specific exercises differed, most of the yoga and stretching class was spent performing exercises designed to stretch and strengthen back and leg muscles (roughly 45 to 50 minutes for yoga versus 60–65 minutes for stretching). Elements unique to the yoga class were 1) breathing exercises and a guided deep relaxation, 2) explicitly asking participants if they had difficulties in performing the postures at home or had any questions and 3) explicit guidance and reminders to practice with awareness of their body. Unique to the stretching class were 5 minutes of warm-up exercises and attempts to create group cohesion through discussion of non-back related topics.

We found yoga was relatively safe. Similar to other kinds of physical movement, harmful outcomes from yoga were mostly temporarily increased back pain,

We were able to identify 8 published clinical trials of yoga for chronic back pain3–6, 8, 9, 22, 23 but no systematic reviews. All included fewer than 50 participants per arm, with five including fewer than 30. The interventions used in these studies differed in many ways, including style of yoga (hatha yoga, Iyengar or viniyoga), hours of class time (from 12 to 72 hours, typically 15 hours), class frequency (from a weeklong retreat of comprehensive yoga to weekly classes of 60 to 90 minutes), and duration of delivery (from 1 to 24 weeks, median=12 weeks). While all studies included postures, breathing exercises and deep relaxation, two added meditation practice. Various control groups included waiting lists (n=3), usual care (n=3), educational information (n=1), and exercise (n=2). Only five studies collected post-intervention follow-up data. Six trials contained serious flaws (e.g., small sample sizes coupled with large baseline imbalances on key outcomes,3, 4, 22 very poor class attendance,23 and high loss to followup8, 9). Despite their diversity, all trials concluded that yoga improved back-related function, symptoms, and/or reduced medication usage.

Recent meta-analyses of exercise for persons with chronic back pain have reported modest but clinically questionable effects of exercise compared with usual care.2, 24, 25 Further analyses found that stretching and strengthening exercises, supervised exercise, and individual tailoring of the exercises were associated with the best outcomes.24 Apart from tailoring, these features were part of our stretching classes.

Our self-care book was included in two trials evaluating slightly different group-based self-care educational interventions.26, 27 Both were found superior to usual care. However, we are unaware of studies that have evaluated it as a stand-alone intervention.

Principal strengths of our study are its relatively large size, well-characterized yoga intervention, inclusion of two comparison groups including one with exercise of comparable physical exertion, high follow-up rates, use of masked interviewers, and satisfactory adherence to the intervention. Moreover, our sensitivity analysis applying a non-ignorable imputation approach to handle missing data confirmed our conclusions.

This study had several limitations: disappointed self-care participants might have been more likely to report worse outcomes, participants were selected from a single site and were relatively well-educated and functional, there was no follow-up beyond 26 weeks, and the amount of stretching performed in the stretching class was substantially greater than typically found in publically available classes.

Yoga or stretching are reasonable treatment options for persons who are willing to engage in physical activities to relieve moderately-impairing back pain. Because yoga classes can vary enormously, clinicians are advised to recommend classes for beginners or that are therapeutically oriented with instructors who are comfortable modifying postures for persons with physical limitations. Clinicians recommending stretching classes should ensure that these contain sufficient back and leg-focused stretching. Patient preferences, availability of suitable classes and patient costs should also be considered. Future studies are needed to determine the usefulness of these interventions for more severely-impaired patients and those of lower socioeconomic status.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the following people for their assistance: study research specialists at Group Health Research Institute: Cheryl Duprey, John Ewing, Erika Holden, Sonia Hinz, Danielle Huston, Mary Lyons, Shirley Meyer, Melissa Parson, and Lisa Shulman; the yoga instructors: Hal Meng, Andrea Murray, Lulu Peele, Abby Staten, Virginia Wise, and an anonymous instructor (all in private practice); the stretching class instructors: Julea Edwards, PT, Martina Eschenburg, PT, Joe Jereczek, PT, John Maisano, PT, Lisa Metzler, PT, Alison Wigstrom-Hoseth, PT. (all with Group Health) and Ned Hartley, PT (private practice); Group Health study clinicians: Lindsay Fleischer, RN, Nancy Hill, RN, Connie Vos, RN. We also thank the interviewers and Staff of the Group Health Research Institute Survey Program for conducting all of the follow-up interviews. We thank Juanita Jackson (employed by Group Health Research Institute) for administrative assistance and Robin Rothenberg (private practice) for training the yoga instructors. All Group Health and private practice staff received compensation for their participation on our study team. We thank Dr. Partap Khalsa from the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine for participation in discussions related to the analysis and interpretation of the data. The principal investigator had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Funding/Support

This study was funded by Cooperative Agreement Number U01 AT003208 from the National Institute for Complementary and Alternative Medicine. Discussions with several NCCAM staff influenced the study design.

Footnotes

Disclaimer

The authors retain sole responsibility for the contents of this publication, which do not necessarily reflect the official views of NCCAM.

Presented at: Primary Care Musculoskeletal Research Congress, Rotterdam, Netherlands, October 12, 2010

References

- 1.Haldeman S, Dagenais S. What have we learned about the evidence-informed management of chronic low back pain? Spine J. 2008 Jan–Feb;8(1):266–277. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2007.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chou R, Huffman LH. Nonpharmacologic therapies for acute and chronic low back pain: a review of the evidence for an American Pain Society/American College of Physicians clinical practice guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2007 Oct 2;147(7):492–504. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-7-200710020-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Galantino ML, Bzdewka TM, Eissler-Russo JL, et al. The impact of modified Hatha yoga on chronic low back pain: a pilot study. Altern Ther Health Med. 2004 Mar–Apr;10(2):56–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Williams KA, Petronis J, Smith D, et al. Effect of Iyengar yoga therapy for chronic low back pain. Pain. 2005 May;115(1–2):107–117. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sherman KJ, Cherkin DC, Erro J, Miglioretti DL, Deyo RA. Comparing yoga, exercise, and a self-care book for chronic low back pain: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2005 Dec 20;143(12):849–856. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-143-12-200512200-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tekur P, Singphow C, Nagendra HR, Raghuram N. Effect of short-term intensive yoga program on pain, functional disability and spinal flexibility in chronic low back pain: a randomized control study. J Altern Complement Med. 2008 Jul;14(6):637–644. doi: 10.1089/acm.2007.0815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Groessl EJ, Weingart KR, Aschbacher K, Pada L, Baxi S. Yoga for veterans with chronic low-back pain. J Altern Complement Med. 2008 Nov;14(9):1123–1129. doi: 10.1089/acm.2008.0020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saper RB, Sherman KJ, Cullum-Dugan D, Davis RB, Phillips RS, Culpepper L. Yoga for chronic low back pain in a predominantly minority population: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Altern Ther Health Med. 2009 Nov–Dec;15(6):18–27. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Williams K, Abildso C, Steinberg L, et al. Evaluation of the effectiveness and efficacy of iyengar yoga therapy on chronic low back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2009 Sep 1;34(19):2066–2076. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181b315cc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sherman KJ, Cherkin DC, Cook AJ, et al. Comparison of yoga versus stretching for chronic low back pain: protocol for the Yoga Exercise Self-care (YES) trial. Trials. 2010;11:36. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-11-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.R Development Core Team. R: A Langage and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical COmputing; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moore JLK, Von Korff M, Gonzalez VM, Laurent DD. The Back Pain Helpbook. Reading, MA: Perseus Books; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bombardier C. Outcome assessments in the evaluation of treatment of spinal disorders: summary and general recommendations. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2000 Dec 15;25(24):3100–3103. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200012150-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sherman KJ, Hawkes RJ, Ichikawa L, et al. Comparing recruitment strategies in a study of acupuncture for chronic back pain. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2009;9:69. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-9-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reiss P. National Center for Health Statistics. DHHS publication PHS 86-1584, 1986. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 1984. Current estimates from the national health interview survey: United States. Vol Vital and health statistics. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cherkin DC, MacCornack FA. Patient evaluations of low back pain care from family physicians and chiropractors. West J Med. 1989 Mar;150(3):351–355. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liang KY, Zeger SL. Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika. 1986;73:13–22. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zou G. A modified poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am J Epidemiol. 2004 Apr 1;159(7):702–706. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.SAS Institute I. SAS/STAT® 9.2 User’s Guide. Cary, NC: SAS Institute, Inc; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang M, Fitzmaurice GM. A simple imputation method for longitudinal studies with non-ignorable non-responses. Biom J. 2006 Apr;48(2):302–318. doi: 10.1002/bimj.200510188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ostelo RW, Deyo RA, Stratford P, et al. Interpreting change scores for pain and functional status in low back pain: towards international consensus regarding minimal important change. Spine. 2008 Jan 1;33(1):90–94. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31815e3a10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jacobs BP, Mehling W, Avins AL, et al. Feasibility of conducting a clinical trial on Hatha yoga for chronic low back pain: methodological lessons. Altern Ther Health Med. 2004 Mar–Apr;10(2):80–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cox H, Tilbrook H, Aplin J, et al. A pragmatic multi-centred randomised controlled trial of yoga for chronic low back pain: trial protocol. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2010 May;16(2):76–80. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2009.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hayden JA, van Tulder MW, Malmivaara AV, Koes BW. Meta-analysis: exercise therapy for nonspecific low back pain. Ann Intern Med. 2005 May 3;142(9):765–775. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-142-9-200505030-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van Middelkoop M, Rubinstein SM, Verhagen AP, Ostelo RW, Koes BW, van Tulder MW. Exercise therapy for chronic nonspecific low-back pain. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2010 Apr;24(2):193–204. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2010.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Von Korff M, Moore JE, Lorig K, et al. A randomized trial of a lay person-led self-management group intervention for back pain patients in primary care. Spine. 1998 Dec 1;23(23):2608–2615. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199812010-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moore JE, Von Korff M, Cherkin D, Saunders K, Lorig K. A randomized trial of a cognitive-behavioral program for enhancing back pain self care in a aprimary care setting. Pain. 2000;88:145–153. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(00)00314-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.