Abstract

Lipids are important substrates for oxidation at rest and during exercise. Aerobic exercise mediates a delayed onset decrease in total and VLDL-triglyceride (TG) plasma concentration. However, the acute effects of exercise on VLDL-TG oxidation and turnover remain unclear. Here, we studied the acute effects of 90 min of moderate-intensity exercise in healthy women and men. VLDL-TG kinetics were assessed using a primed constant infusion of ex vivo labeled [1-14C]triolein VLDL-TG. Fractional VLDL-TG-derived fatty acid oxidation was measured from 14CO2 specific activity in expired air. VLDL-TG concentration was unaltered during exercise and early recovery, whereas non-VLDL-TG concentration decreased significantly.VLDL-TG secretion rate decreased significantly during exercise and remained suppressed during recovery. Total VLDL-TG oxidation rate was unaffected by exercise. However, the contribution of VLDL-TG oxidation to total energy expenditure fell from 14 ± 9% at rest to 3 ± 4% during exercise. We conclude that VLDL-TG fatty acids are quantitatively important oxidative substrates under basal postabsorptive conditions but remain unaffected during 90-min moderate-intensity exercise and, thus, become relatively less important during exercise. Lower VLDL secretion rate during exercise may contribute to the decrease in TG concentrations during and after exercise.

Keywords: very low density lipoprotein, tracer studies

elevated plasma triglycerides (TG) as well as lipoprotein subclass composition have been demonstrated to independently predict development of cardiovascular disease (CVD). In addition, hypertriglyceridemia is a prominent feature of diabetic dyslipidemia and strongly related to diabetes comorbidity (1, 12). Regular exercise, on the other hand, counteracts dyslipidemia and reduces the risk of CVD (13). However, the immediate effects of exercise on TG kinetics and subclass distribution are unknown.

Fatty acids are important oxidative substrates both at rest and during exercise (14). During exercise, fatty acid oxidation can increase 5–10 times above resting levels, with maximum oxidation rates observed at exercise intensities ∼65% of maximal oxygen uptake (V̇o2max) (14). Fatty acids for oxidation can originate from circulating free fatty acids (FFA), intramyocellular triacylglycerol, and plasma very low density lipoprotein-triacylglycerol (VLDL-TG)-derived fatty acids. Plasma FFA are the quantitatively most important contributor to lipid oxidation, but studies have shown that FFA oxidation measured with isotopic tracers and total lipid oxidation measured with indirect calorimetry differs (9), indicating oxidation of other lipid sources. We recently demonstrated that VLDL-TG contribute as much as 10–15% of the total energy expenditure (EE) in the resting postabsorptive state (7). However, it remains unknown to what extent VLDL-TG contributes to EE during exercise.

Previous studies have not been able to demonstrate any consistent changes in the plasma concentration of total TG during or immediately after exercise (22), but several studies have demonstrated a decrease in plasma TG the day after an exercise bout (2, 29). A single bout of exercise increases the removal of VLDL-TG from plasma on the following day (2, 19, 30). Only one study, however, has investigated the changes in VLDL-TG kinetics during exercise. The authors found an increase in the fractional catabolic rate of VLDL-TG but no differences in the VLDL-TG concentration (22), indicating that both VLDL-secretion and clearance were increased.

Measuring acute changes in VLDL turnover presents some difficult challenges, since most previous studies have involved precursor labeling with FFA (25) or glycerol (16) and subsequent blood sampling and mathematical modeling. Although these methods allow measurement of plasma clearance of VLDL-TG, they do not permit direct measurement of the amount of plasma VLDL-TG that is oxidized.

The purpose of this study was to determine the acute effects of moderate-intensity aerobic exercise on VLDL-TG kinetics in young, lean, healthy men and women. We used an ex vivo labeled VLDL-TG tracer that allowed us to directly measure the oxidation of VLDL-TG from measurements of 14CO2 specific activity (SA) in expired air (5) as well as plasma VLDL-TG kinetics. Our primary aim was to assess the acute effect of exercise on VLDL-TG fatty acid oxidation. As a secondary aim, we wanted to assess the acute effects of exercise on VLDL-TG secretion and clearance. A third aim was to test for any sex-specific differences in VLDL-TG kinetics.

METHODS

Participants

The study protocol was approved by the local Ethics Committee and written informed consent was obtained from all participants. Eight lean men and 8 lean women (age 20–30 yr, BMI <25 kg/m2) were recruited through posters at local educational institutions. The volunteers were recreationally active but untrained (participated in moderate-intensity physical activities ≤3 h/wk). All participants were normotensive, nonsmokers, used no medication except oral contraceptives, and had a normal blood count and chemistry panel.

Potentially eligible subjects visited the Clinical Research Laboratories after an overnight 10- to 12-h fast. Blood was obtained for determination of a lipid profile, Hb A1c, liver, kidney, and thyroid function, and complete blood count and chemistry panel. Medical history was taken and a physical examination performed including evaluation of inclusion/exclusion criteria.

Protocol

One week prior to the metabolic study day, volunteers came to the Research Laboratories after an overnight fast of 10–12 h. A 60-ml blood sample was drawn for ex-vivo labeling of VLDL-TG. V̇o2max was determined by an incremental (20 W/min) cycling protocol until exhaustion (Oxycon Pro, Erich Jaeger). At the same visit, a dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) scan was performed to determine body composition. Participants were then interviewed by a dietitian, who estimated their daily caloric intake. On the basis of the dietitian's calculations the participants were provided a weight-maintaining diet (55% carbohydrate, 15% protein, and 30% fat) provided by the hospital kitchen during the 3 days preceding the metabolic study.

Metabolic study day.

Volunteers were admitted to the Clinical Research Laboratories at 2200 the evening before the study. From this time point, only ingestion of tap water was allowed. The study day, starting at 0700, included a 5-h basal period (0–300 min), a 1.5-h cycling exercise period at 50% of V̇o2max (300–390 min) and a 2-h recovery period (390–510 min). On the morning of the study day, catheters were placed in an antecubital vein and a contralateral heated hand vein to obtain arterialized blood. The antecubital catheter was used for the primed constant infusion of [1-14C]triolein-labeled VLDL (priming with 20% of labeled VLDL) and a constant infusion of [9,10-3H]palmitate for 1 h in both the basal period (180–240 min) and during exercise (330–390 min). The other catheter was used for sampling of plasma VLDL-TG SA (t = 0, 180, 210, 240, 270, 300, 315, 330, 345, 360, 375, 390, 405, 420, 450, 480, and 510 min). Breath samples were obtained every 60 min during the basal period, every 15 min during the exercise period, and every 30 min during recovery period to determine 14CO2 SA. Indirect calorimetry was performed for 30 min from t = 210 min and continuously during the exercise period to determine the rate of CO2 production (V̇co2) and O2 consumption (V̇o2). After the blood sampling at 510 min, all catheters were removed.

VLDL-TG tracer preparation.

The ex vivo labeling procedure of VLDL-TG with radiolabeled triolein has previously been described in detail (5). Briefly, plasma obtained from a 60-ml blood sample was mixed with [1-14C]triolein (PerkinElmer), and sonicated in an incubator at 37°C for 6 h. To isolate the [1-14C]triolein-labeled VLDL particles, labeled plasma was then transferred to sterile Optiseal test tubes (Beckman Instruments), covered with a saline solution (d = 1.006 g/ml) and centrifuged in an ultracentrifugator (50.3 Ti rotor, Beckman Instruments) for 18 h at 40,000 rpm at 10°C. The supernatant containing the labeled VLDL fraction was removed with a sterile Pasteur pipette, filtered, and stored at 5°C. All samples were cultured to ensure sterility.

Plasma VLDL-TG concentration and SA.

VLDL particles were isolated from ∼3 ml of plasma by ultracentrifugation as described above. The top layer, containing VLDL, was obtained by slicing the tube ∼1 cm from the top using a tube slicer (Beckman Instruments). A small proportion was analyzed for TG content, and the plasma concentration of VLDL-TG was calculated. The remaining VLDL-TG was transferred to a scintillation glass vial, scintillation liquid was added, and the sample was measured for 14C activity using liquid scintillation counting to <2% counting error.

Breath 14CO2 activity.

Breath samples were collected in breath bags (IRIS-Breath-Bags, Wagner Analysen Technik). The exhaled air was passed through a solution containing benzethonium hydroxide (Sigma-Aldrich) with thymolphthalein (Sigma-Aldrich) in a scintillation vial. A color change occurred when exactly 0.25 mmol CO2 was trapped. Scintillation fluid was added, and 14C activity was measured by liquid scintillation counting to a <2% counting error.

Palmitate turnover.

Systemic palmitate flux was measured using the isotope dilution technique with a constant infusion of [9,10-3H]palmitate (Dept. of Nuclear Medicine, Aarhus University Hospital) (8). Plasma palmitate concentration and SA were measured at baseline and at 10-min intervals over the last 30 min of the infusion periods by HPLC using [2H31]palmitate as internal standard. Steady-state SA was verified for each individual. Palmitate flux (μmol/min) was calculated as [9,10-3H]palmitate infusion rate divided by the steady-state palmitate SA.

Body composition.

Total body fat, leg fat, fat percentage, and fat-free mass were measured by DEXA (QDR-2000).

Indirect calorimetry.

REE and substrate oxidation rates were measured by indirect calorimetry (Deltatrac monitor, Datex Instruments). During exercise V̇co2and V̇o2 were measured by Oxycon Pro (Erich Jaeger).

Calculations

VLDL-TG secretion.

VLDL-TG SA steady state was reached during the last 3 h of the basal period, the last half-h of the exercise period, and the last half-hour of the recovery period. VLDL-TG Ra (μmol/min) was calculated by dividing the infusion rate by the plateau SA in each period:

VLDL-TG clearance.

VLDL-TG clearance (ml/min) was calculated by dividing the secretion rate by the average VLDL-TG concentration in each period:

VLDL-TG oxidation.

Fractional oxidation (%) of the infused [1-14C]VLDL-TG was calculated as follows:

where k is the volume of 1 mole of CO2 at 20°C and 1 atm. Pressure (22.4 l/mol) and Ar is the fractional acetate carbon recovery factor in breath CO2, and F is the tracer infusion rate. Sidossis et al. (24) have previously estimated Ar to be 0.56 for resting conditions (24). During exercise, we used a correction factor of 0.98 estimated by Van Loon et al. (31) with a preexercise infusion time of 4 h resembling our protocol.

Total VLDL-TG oxidation rate (μmol/min) was calculated as

Energy production (kcal/day) from VLDL-TG was calculated using the molecular weight of 282 g/mol of oleic acid and multiplied the caloric density by 9.1 kcal/g and 1,440 min/day.

Statistics

Data were analyzed with SPSS 17.0. Normality was tested with a Shapiro-Wilk normality test. Data are expressed as means ± SD or median (range). Differences between groups were evaluated using Student's t-test or Mann-Whitney test. Student's t-test for paired samples was used to evaluate the effect of exercise on oxidation. Analyses of effects of exercise and recovery on TG concentrations and VLDL turnover were performed using repeated-measures ANOVA with factors for sex and time. In the case of a time effect, comparison between the different periods was made with Student's t-test for paired samples. Significance was set at P = 0.05.

RESULTS

Baseline data of the subjects are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Basal characteristics

| Subjects | Male | Female | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 8 | 8 | |

| Age, yr | 22 (20–29) | 22 (21–27) | 1.00 |

| Weight, kg | 80.2 ± 6.7 | 64.9 ± 6.6 | <0.01 |

| Height, m | 1.86 ± 0.05 | 1.71 ± 0.03 | <0.01 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 23.1 ± 1.2 | 22.3 ± 1.9 | 0.33 |

| Waist-to-hip ratio | 0.84 ± 0.03 | 0.78 ± 0.05 | 0.02 |

| Lean body mass, kg | 62.1 ± 5.8 | 43.3 ± 3.0 | <0.01 |

| Total fat mass, kg | 13.0 ± 3.1 | 17.9 ± 4.6 | 0.03 |

| Fat, % | 16.6 ± 3.7 | 27.8 ± 4.2 | <0.01 |

| V̇o2max, ml · min–1 · kg–1 | 49.6 ± 5.8 | 39.3 ± 7.6 | <0.01 |

Values are means ± SD or median (range).

Substrate Concentration And Palmitate Turnover

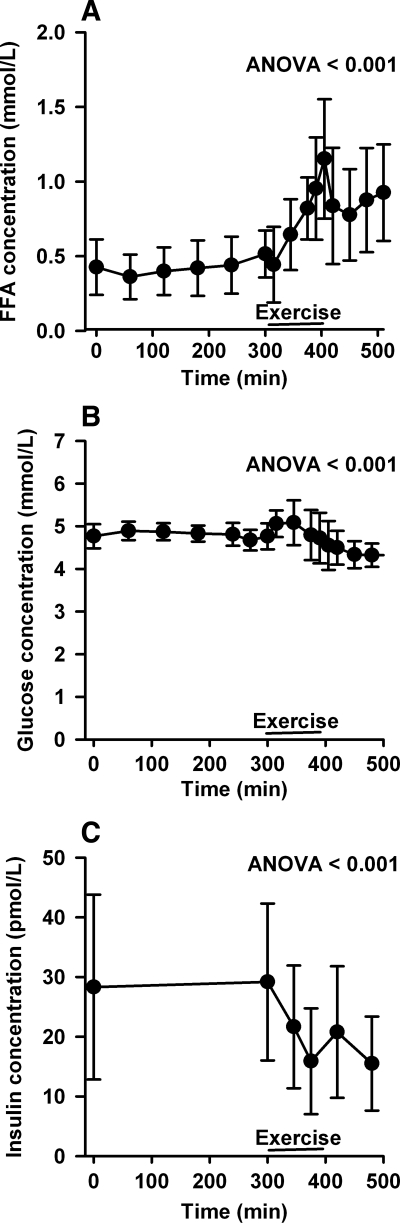

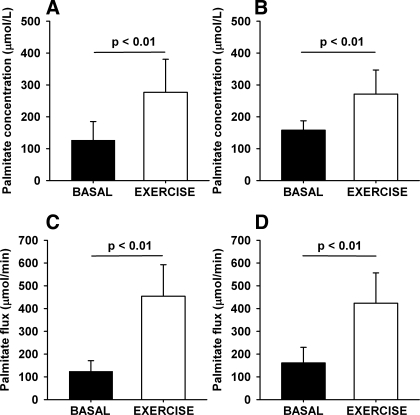

FFA, glucose, and insulin concentrations during the study day are shown in Fig. 1. As expected, during exercise, FFA and glucose concentration increased, whereas insulin concentration decreased. Basal palmitate concentration was comparable in men and women [men: 127 ± 59 μmol/l; women: 158 ± 29 μmol/l (P = 0.20)] and increased equally in men and women during exercise [men: 277 ± 104 μmol/l (P < 0.01); women: 271 ± 75 μmol/l (P < 0.01); Fig. 2, A and B]. Basal palmitate flux was comparable in men and women [men: 125 ± 46 μmol/min; women: 161 ± 68 μmol/min (P = 0.23)] and, as expected, increased dramatically during exercise [men: 454 ± 138 μmol/min (P < 0.01); women: 424 ± 133 μmol/min (P < 0.01); Fig. 2, C and D].

Fig. 1.

Substrate and hormone concentrations. A: free fatty acid (FFA) concentration (mmol/l). B: glucose concentration (mmol/l). C: insulin concentration (pmol/l). Error bars are SD.

Fig. 2.

Palmitate turnover. A and B: palmitate concentration (μmol/l). C and D: palmitate flux (μmol/min). A and C: men. B and D: women. Error bars are SD.

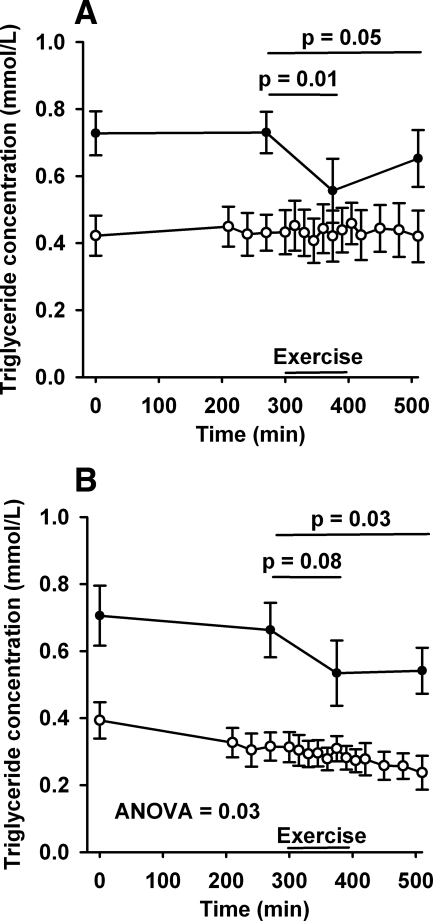

TG Concentration

Basal plasma total TG concentration was stable at 0.73 ± 0.18 mmol/l in men and 0.66 ± 0.22 mmol/l in women. During exercise, total TG concentrations decreased to 0.56 ± 0.27 mmol (P = 0.01) in men and trended toward a decrease in women to 0.53 ± 0.14 mmol/l (P = 0.08) in women (Fig. 3). After cessation of exercise, the total TG concentrations remained lower compared with basal levels at 0.65 ± 0.24 mmol (P = 0.05) in men and 0.54 ± 0.18 mmol/l (P = 0.03) in women. In contrast, VLDL-TG concentrations in men remained unchanged over the study day [basal: 0.43 ± 0.18 mmol/l; exercise: 0.43 ± 0.20; recovery: 0.43 ± 0.22 ANOVA (P = 0.95)], whereas a slight but significant decrease was observed in women [basal: 0.27 ± 0.15 mmol/l; exercise: 0.24 ± 0.10; recovery: 0.20 ± 0.11 ANOVA (P = 0.03)].

Fig. 3.

Triglyceride concentration. Plasma concentration of total TG (□) and VLDL-TG (○) (mmol/l). A: men; B: women. Error bars are SD.

VLDL Kinetics

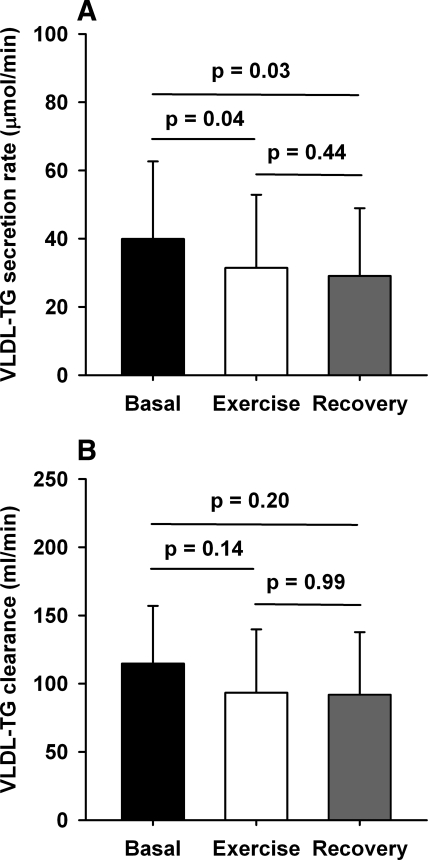

VLDL-TG turnover.

There were no sex-related significant differences in the secretion rates over the study day (ANOVA, P = 0.81); therefore, we used combined data for the analysis of VLDL kinetics. VLDL-TG secretion rate changed significantly from baseline during the study (39.9 ± 22.7 vs. 31.4 ± 21.5 vs. 29.1 ± 19.9 μmol/min in basal, exercise, and recovery periods, respectively, ANOVA, P = 0.03). The decrease during both exercise and recovery was significant compared with basal conditions (both P = 0.03; Fig. 4A). No significant differences were found in VLDL-TG clearance rates (115 ± 42 vs. 93 ± 46 vs. 92 ± 46 ml/min in basal, exercise, and recovery periods, respectively, ANOVA, P = 0.25), with no significant sex-related differences in clearance rates over the study day (ANOVA P = 0.85).

Fig. 4.

VLDL kinetics. A: VLDL-TG secretion rate (μmol/min) (ANOVA = 0.03). B: VLDL-TG clearance rate (ml/min) (ANOVA = 0.25). Error bars are SD.

VLDL-TG oxidation.

Total EE increased during exercise in both men [basal: 1.31 ± 0.13 kcal/min; exercise: 8.78 ± 1.27 kcal/min (P < 0.001)] and women [basal: 1.02 ± 0.09 kcal/min; exercise: 5.19 ± 0.97 kcal/min (P < 0.001)]. There was a decrease in respiratory exchange ratio (RER) in women [basal: 0.83 ± 0.05; exercise 0.74 ± 0.02 (P < 0.01)], demonstrating a shift to a proportionally greater total lipid oxidation. In men, RER did not decrease significantly [basal: 0.83 ± 0.04; exercise 0.81 ± 0.04 (P = 0.14)]. The proportion of total EE accounted for by lipid oxidation increased during exercise in both men [basal: 0.48 ± 0.14; exercise 0.64 ± 0.14 (P < 0.001)] and women [basal: 0.44 ± 0.17; exercise 0.87 ± 0.08 (P < 0.001)].

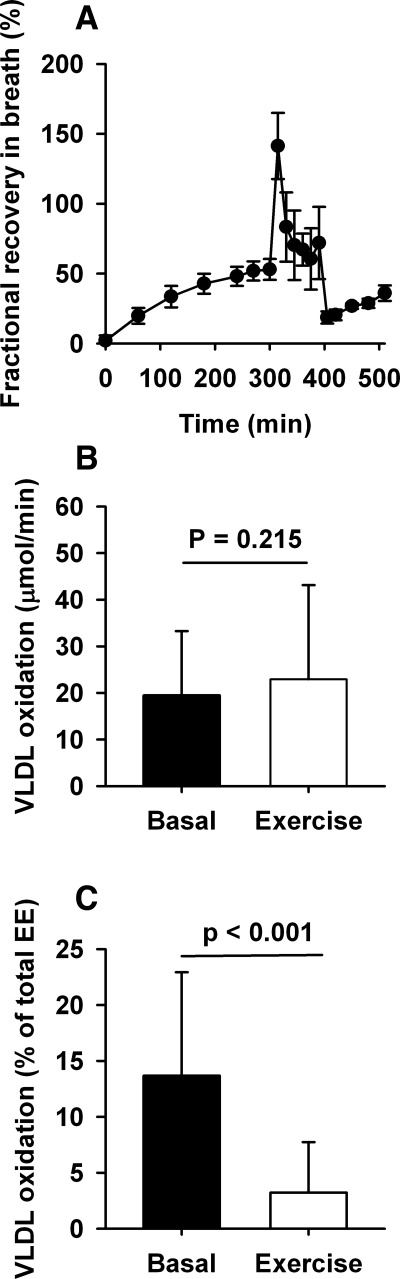

In the basal period, the proportion of the secreted VLDL-TG that was oxidized (fractional oxidation) was 50 ± 8%. Due to a release of fixated 14C label from other carbon pools in response to onset of exercise, there was an expected peak in fractional recovery immediately after the onset of exercise followed by a gradually reached plateau. In the plateau phase, a significantly greater proportion of the secreted VLDL-TG was oxidized [84 ± 35% (P < 0.01); Fig. 5A]. During the recovery, 14CO2 steady state was not achieved, and oxidation rates could not be calculated.

Fig. 5.

VLDL oxidation. A: proportion of secreted VLDL-TG oxidized (μmol/min). B: VLDL-TG oxidation rate (μmol/min) in the basal period and in the exercise period. C: contribution of VLDL-TG oxidation to total energy expenditure (EE; %) in the basal period and in the exercise period. Error bars are SD.

During exercise, absolute oxidation rates of VLDL-TG increased slightly compared with basal rates [basal: 20 ± 14 μmol/min; exercise: 23 ± 20 μmol/min (P = 0.22)], despite a grossly increased total EE (Fig. 5B). During the basal period, oxidation of VLDL-TG contributed with 14 ± 9% to total EE with no sex-related differences. Due to the absence of increase in the VLDL-TG oxidation rate during exercise, the contribution of VLDL-TG oxidation to total EE decreased to 3 ± 4% (P < 0.01) in the exercise period (Fig. 5C).

DISCUSSION

The main findings of these studies are that the oxidation rate of VLDL-TG-associated fatty acids contributes significantly to resting EE but remains unchanged during 1.5 h of moderate-intensity exercise in healthy, lean men and women despite a severalfold increase in lipid oxidation. Moreover, the VLDL-TG secretion rate decreases during exercise, a reduction that extends into early recovery. Finally, no sex-specific differences in VLDL kinetics are revealed.

As a novel finding, we demonstrate that, despite an exercise-induced sixfold increase in EE, the oxidation of VLDL-TG expressed in absolute terms remained unchanged. As expected, the palmitate flux increased three- to fourfold during exercise, delivering FFAs for the increased lipid oxidation. We confirmed previous reports of a greater decrease in RER during exercise in women compared with men (28). Measurements of a-v TG concentration differences during exercise suffer from the lack of reliability of TG assays to pick up the small concentration differences during high blood flow states as well as the assumption that all fatty acids removed in the leg are oxidized (10). We measured the oxidation directly, and we can therefore exclude VLDL-TG storage in muscle or adipose tissue from our calculations of VLDL-TG oxidation. During rest, VLDL-TG oxidation accounted for 14% of the total EE, decreasing to only 3% of the total EE during exercise. We have previously demonstrated that VLDL-TG oxidation contributes 10–15% of the total EE in lean and obese women and in obese and diabetic men (7, 26). We conclude that in lean healthy individuals on a low/normal-fat diet VLDL-TG does not play a significant role as substrate for the increased lipid oxidation during exercise. This does not, however, exclude VLDL-TG as an important substrate for oxidation during exercise in obese or exercise-trained individuals or during high-fat diets.

We found a significant decrease in VLDL-TG secretion rate during exercise and in accord with previous reports from our own group (6) as well as others (3, 17, 23), although not all (20, 21); we found no difference in basal VLDL-TG secretion between men and women. Moreover, we also noted a slight, although not significant decrease in VLDL-TG clearance rate. In the only other published study of VLDL kinetics during exercise, Morio et al. (22) found an increase in fractional catabolic rate during exercise, which is in contrast to our findings of a decrease in VLDL-TG secretion rate and a slight decrease in clearance. This discrepancy may relate to differences in workload and duration of exercise (45 min at 40% of V̇o2max vs. 90 min at 50% of V̇o2max in our study). Studies of VLDL-TG metabolism have shown that a single bout of exercise increases VLDL-TG removal from plasma the following day, whereas no changes in secretion rates are observed (18, 19, 30). It needs further studying to determine how long the reduction in secretion rate persists after an exercise bout and to what degree this influences the delayed onset decrease in VLDL-TG concentration seen after exercise.

Several authors have reported a delayed decrease in TG concentration after exercise (19, 29) but have not demonstrated consistent changes in TG concentration during exercise or immediately after exercise. We found an ∼20% decrease in total TG concentration during 1.5 h of exercise that persisted during the 2 h of recovery. Previous reports have described elevated (11), unchanged (4), or decreased (15) concentrations of total TG immediately after exercise, whereas there is agreement regarding the unchanged levels of VLDL-TG (19, 22). This may relate to differences in exercise intensity in the studies as well as the physical fitness of the subjects investigated. In the present study, we used recreationally active but untrained men and women during moderate-intensity exercise (50% of V̇o2max) resembling everyday exercise, whereas others have studied extremely well-trained individuals after high-intensity exercise such as marathon runners after completing a marathon (11) and triathletes after an Ironman race (15).

A limitation to our study is the possibility of tracer recycling. However, the tracer recycling problem represents a minor problem in constant-infusion protocols, since recycled labeled VLDL-TG contributes a minor proportion to steady-state SA when final VLDL-TG Ra is calculated, as discussed in detail in a previous paper from our group (27).

In conclusion, fatty acids from VLDL-TG are quantitatively important substrates for lipid oxidation under basal postabsorptive conditions, but VLDL-TG oxidation rates remain unchanged during moderate-intensity exercise. We demonstrate a lower VLDL-TG secretion rate, which may contribute to postexercise hypotriglyceridemia. Finally, VLDL-TG kinetics appear similar in lean men and women.

GRANTS

This work was supported by grants from the Danish Medical Research Council, the Novo Nordic Foundation, and the Danish Diabetes Foundation (to S. Nielsen).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest are reported by the authors.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge the excellent technical assistance of Lone Kvist and Susanne Sørensen of the Medical Research Laboratorium, Aarhus University Hospital.

REFERENCES

- 1. Adler AI, Stevens RJ, Neil A, Stratton IM, Boulton AJ, Holman RR. UKPDS 59: hyperglycemia and other potentially modifiable risk factors for peripheral vascular disease in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 25: 894–899, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Annuzzi G, Jansson E, Kaijser L, Holmquist L, Carlson LA. Increased removal rate of exogenous triglycerides after prolonged exercise in man: Time course and effect of exercise duration. Metabolism 36: 438–443, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Carpentier A, Patterson BW, Leung N, Lewis GF. Sensitivity to acute insulin-mediated suppression of plasma free fatty acids is not a determinant of fasting VLDL triglyceride secretion in healthy humans. Diabetes 51: 1867–1875, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ferguson MA, Alderson NL, Trost SG, Davis PG, Mosher PE, Durstine JL. Plasma lipid and lipoprotein responses during exercise. Scand J Clin Lab Invest 63: 73–79, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gormsen LC, Jensen MD, Nielsen S. Measuring VLDL-triglyceride turnover in humans using ex vivo-prepared VLDL tracer. J Lipid Res 47: 99–106, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gormsen LC, Jensen MD, Schmitz O, Moller N, Christiansen JS, Nielsen S. Energy expenditure, insulin, and VLDL-triglyceride production in humans. J Lipid Res 47: 2325–2332, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gormsen LC, Nellemann B, Sorensen LP, Jensen MD, Christiansen JS, Nielsen S. Impact of body composition on very-low-density lipoprotein-triglycerides kinetics. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 296: E165–E173, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Guo Z, Nielsen S, Burguera B, Jensen MD. Free fatty acid turnover measured using ultralow doses of [U-13C]palmitate. J Lipid Res 38: 1888–1895, 1997 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Heiling VJ, Miles JM, Jensen MD. How valid are isotopic measurements of fatty acid oxidation? Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 261: E572–E577, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Helge JW, Watt PW, Richter EA, Rennie MJ, Kiens B. Fat utilization during exercise: adaptation to a fat-rich diet increases utilization of plasma fatty acids and very low density lipoprotein-triacylglycerol in humans. J Physiol 537: 1009–1020, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kobayashi Y, Takeuchi T, Hosoi T, Yoshizaki H, Loeppky JA. Effect of a marathon run on serum lipoproteins, creatine kinase, and lactate dehydrogenase in recreational runners. Res Q Exerc Sport 76: 450–455, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Koskinen P, Manttari M, Manninen V, Huttunen JK, Heinonen OP, Frick MH. Coronary heart disease incidence in NIDDM patients in the Helsinki Heart Study. Diabetes Care 15: 820–825, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kraus WE, Houmard JA, Duscha BD, Knetzger KJ, Wharton MB, McCartney JS, Bales CW, Henes S, Samsa GP, Otvos JD, Kulkarni KR, Slentz CA. Effects of the Amount and Intensity of Exercise on Plasma Lipoproteins. N Engl J Med 347: 1483–1492, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Krogh A, Lindhard J, Liljestrand G, Andresen KG. The relative value of fat and carbohydrate as sources of muscular energy. With appendices on the correlation between standard metabolism and the respiratory quotient during rest and work. Biochem J 14: 290–363, 1920 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lamon-Fava S, McNamara JR, Farber HW, Hill NS, Schaefer EJ. Acute changes in lipid, lipoprotein, apolipoprotein, and low-density lipoprotein particle size after an endurance triathlon. Metabolism 38: 921–925, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lemieux S, Patterson BW, Carpentier A, Lewis GF, Steiner G. A stable isotope method using a [2H5]glycerol bolus to measure very low density lipoprotein triglyceride kinetics in humans. J Lipid Res 40: 2111–2117, 1999 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lewis GF, Uffelman KD, Szeto LW, Steiner G. Effects of acute hyperinsulinemia on VLDL triglyceride and VLDL apoB production in normal weight and obese individuals. Diabetes 42: 833–842, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Magkos F, Tsekouras YE, Prentzas KI, Basioukas KN, Matsama SG, Yanni AE, Kavouras SA, Sidossis LS. Acute exercise-induced changes in basal VLDL-triglyceride kinetics leading to hypotriglyceridemia manifest more readily after resistance than endurance exercise. J Appl Physiol, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Magkos F, Wright DC, Patterson BW, Mohammed BS, Mittendorfer B. Lipid metabolism response to a single, prolonged bout of endurance exercise in healthy young men. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 290: E355–E362, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mittendorfer B, Patterson BW, Klein S. Effect of sex and obesity on basal VLDL-triacylglycerol kinetics. Am J Clin Nutr 77: 573–579, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mittendorfer B, Patterson BW, Klein S, Sidossis LS. VLDL-triglyceride kinetics during hyperglycemia-hyperinsulinemia: effects of sex and obesity. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 284: E708–E715, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Morio B, Holmback U, Gore D, Wolfe RR. Increased VLDL-TAG turnover during and after acute moderate-intensity exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc 36: 801–806, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Nikkila EA, Kekki M. Polymorphism of plasma triglyceride kinetics in normal human adult subjects. Acta Med Scand 190: 49–59, 1971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sidossis LS, Coggan AR, Gastaldelli A, Wolfe RR. A new correction factor for use in tracer estimations of plasma fatty acid oxidation. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 269: E649–E656, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sidossis LS, Magkos F, Mittendorfer B, Wolfe RR. Stable isotope tracer dilution for quantifying very low-density lipoprotein-triacylglycerol kinetics in man. Clin Nutr 23: 457–466, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sørensen LP, Andersen IR, Søndergaard E, Gormsen LC, Schmitz O, Christiansen JS, Nielsen S. Basal and insulin mediated VLDL-triglyceride kinetics in type 2 diabetic men. Diabetes 60: 88–96, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sorensen LP, Gormsen LC, Nielsen S. VLDL-TG kinetics: a dual isotope study for quantifying VLDL-TG pool size, production rates, and fractional oxidation in humans. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 297: E1324–E1330, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tarnopolsky MA, Atkinson SA, Phillips SM, MacDougall JD. Carbohydrate loading and metabolism during exercise in men and women. J Appl Physiol 78: 1360–1368, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Thompson PD, Cullinane E, Henderson LO, Herbert PN. Acute effects of prolonged exercise on serum lipids. Metabolism 29: 662–665, 1980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Tsekouras YE, Magkos F, Prentzas KI, Basioukas KN, Matsama SG, Yanni AE, Kavouras SA, Sidossis LS. A single bout of whole-body resistance exercise augments basal VLDL-triacylglycerol removal from plasma in healthy untrained men. Clin Sci (Lond) 116: 147–156, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. van Loon LJC, Koopman R, Schrauwen P, Stegen J, Wagenmakers AJM. The use of the [1,2–13C]acetate recovery factor in metabolic research. Eur J Appl Physiol 89: 377–383, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]