Abstract

In Korea, many people enjoy eating raw or underkooked freshwater crayfish and crabs which unfortunately may cause paragonimiasis. Here, we describe a case of pulmonary and abdominal paragonimiasis in a 9-year-old girl, who presented with a 1-month history of abdominal pain, especially in the right flank and the right inguinal area, with anorexia. A chest radiograph revealed pleural effusion in both lungs, and her abdominal sonography indicated an inflammatory lesion in the right psoas muscle. Peripheral blood analysis of the patient showed hypereosinophilia (66.0%) and an elevated total serum IgE level (>2,500 IU/ml). The pleural effusion tested by ELISA were also positive for antibodies against paragonimiasis. Her dietary history stated that she had ingested raw freshwater crab, 4 months previously. The diagnosis was pulmonary paragonimiasis accompanied by abdominal muscle involvement. She was improved after 5 cycles of praziquantel treatment and 2 times of pleural effusion drainage. In conclusion, herein, we report a case of pulmonary and abdominal paragonimiasis in a girl who presented with abdominal pain and tenderness in the inguinal area.

Keywords: Paragonimiasis, crab, abdominal pain, pleural effusion, abdominal muscle

INTRODUCTION

Paragonimiasis is a parasitic disease caused by Paragonimus trematodes, commonly known as the lung fluke. More than 8 species of Paragonimus are known to infect humans worldwide. The most common species, Paragonimus westermani, is distributed mainly in South Korea, Japan, India, and other Southeast Asian countries. Human paragonimiasis is caused by ingestion of raw or incompletely cooked freshwater crabs or crayfish infected with metacercariae of the lung fluke [1-4]. Although the rate of infection and incidence are low in many countries; however, in Korea, patients still commonly present with paragonimiasis. Koreans, in general, enjoy eating raw freshwater crabs or crayfish, especially as a part of the traditional Korean dish, called 'Kejang', prepared by soaking freshwater crabs in soybean sauce, which may lead to paragonimiasis [5-7].

Patients with paragonimiasis are usually adults, presenting with signs and symptoms in their lower respiratory tract. The overriding symptoms are cough, hemoptysis, or dyspnea, some of which overlap with tuberculosis and other pulmonary disorders. While only a few pediatric cases have been described in the literature [8-10], we report a rare case of combined pulmonary and abdominal paragonimiasis in a 9-year-old Korean girl who suffered from abdominal pain and tenderness in the right inguinal area for 1 month.

CASE RECORD

A 9-year-old girl who lived in Inchon city, Korea, presented at a local hospital with a 2-day history of mild fever and a 1-month history of abdominal pain, in particular, pain in the right flank and right inguinal area. During this month, she experienced 2 kg weight loss with anorexia. The physician treating her at the local hospital suspected acute appendicitis, and, therefore, advised abdominal CT, in order to identify the cause of the abdominal pain. However, the results showed both pleural effusion and small amount of ascites in the abdominal and pelvic cavities. Therefore, she was referred to our hospital for further evaluation. She had previously been treated for allergic rhinitis and atopic dermatitis, and she visited a Sumjin River area and consumed 'Kejang', which was prepared using crabs from the Sumjin River, 4 months before. Other members of her family did not consume this traditional dish.

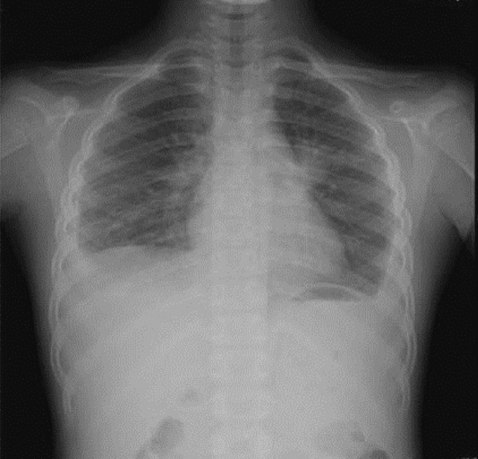

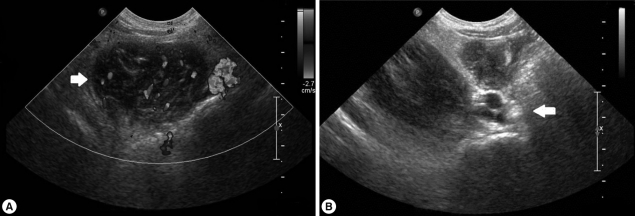

On admission, her vital signs were as follows: body temperature, 37.8℃; heart rate, 90/min; respiratory rate, 24/min; and blood pressure, 100/70 mmHg. On examination, she looked very ill and her breathing sounds were decreased on both sides of the lower chest. Moderate tenderness was detected in the right flank and the right inguinal area. A chest radiograph indicated pleural effusion (Fig. 1), and abdominal sonography revealed an inflammatory lesion in the right psoas muscle (Fig. 2). Her total white blood cell (WBC) count was 26,900 cells/mm3, hemoglobin level was 10.7 g/dl, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was 75 mm/hr, and C-reactive protein concentration was 71 mg/dl. The patient also presented with hypereosinophilia (66%), and the total serum IgE value higher than 2,500 IU/ml. Because her dietary history and laboratory findings were indicative of a parasitic infection, we performed a serum antibody test using ELISA and examined her stool, sputum, and pleural fluid specimens [11]. No evidence of parasite eggs in the stool or sputum specimen was obtained, but ELISA was positive for P. westermani in the serum, with an optical density (OD) of 0.619 (cut-off OD: 0.255). The pleural fluid obtained by thoracentesis revealed the following findings: WBC, 26,200 cells/mm3 (neutrophils, 25%; lymphocytes, 72%); pH, 7.129; proteins, 8.2 g/dl; albumin, 2.1 g/dl; glucose, 5 mg/dl; and turbid appearance. Gram staining, culture studies, and tuberculosis- PCR (TB-PCR) in the pleural fluid, however, were negative.

Fig. 1.

Chest radiograph on first admission. Pleural effusion is visible in both the lower lungs.

Fig. 2.

Abdominal sonogram on first admission. (A) A low-echoic lesion measuring 2 cm with inflammation of the surrounding fat in the medial right psoas lesion (arrow). (B) Swelling of the right inguinal area with enlarged lymph nodes (arrow).

Praziquantel therapy was initiated at a dose of 25 mg/kg, 3 times a day for 2 days. Two days after admission, fever subsided, the pleural effusion decreased, the abdominal pain improved, and the follow-up chest radiograph showed improvement. On the 6th day of hospitalization, she was discharged. However, at the next follow-up visit, her peripheral blood was still positive for hypereosinophilia (74.9%); therefore, an additional cycle of praziquantel therapy was recommended.

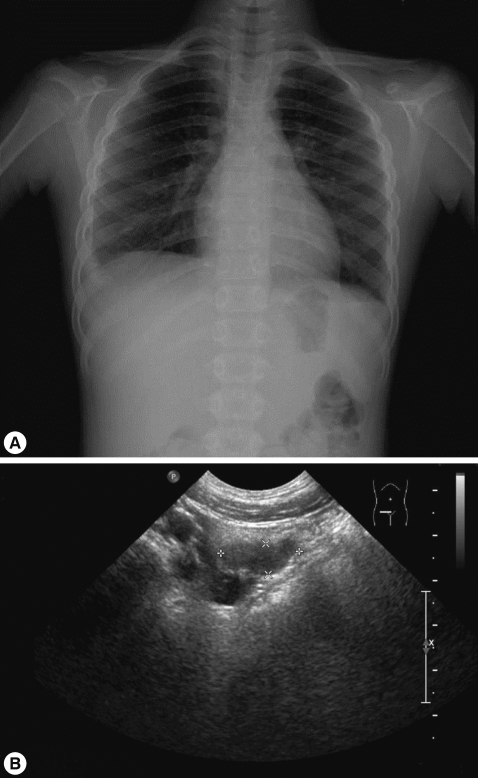

One month after the first admission, the eosinophil count in the peripheral blood and the total serum IgE value were still high (eosinophils, 37.4%; IgE, 1,094 IU/ml). The follow-up chest radiograph showed improvements of the left pleural effusion, but persistence of the right pleural effusion (Fig. 3A). She was, therefore, readmitted to the hospital, and the pleural fluid was drained using a pigtail catheter.

Fig. 3.

Chest radiograph and abdominal sonogram on the second admission. (A) Right pleural effusion is still present. (B) A slightly smaller lesion is visible in the right lower quadrant of the abdomen.

Analysis of the drained pleural fluid showed the following results: WBC, 250 cells/mm3 (neutrophils, 8%; lymphocytes, 49%); pH, 7.164; protein, 9.8 g/dl; albumin, 2.7 g/dl; glucose, 4 mg/dl; and amber colored appearance. Gram staining and culture studies of the pleural fluid were negative, but P. westermani-specific IgG antibody was strongly positive in the pleural fluid, with an OD of 1.576 (cut-off OD: 0.002). Abdominal sonography revealed a smaller, albeit still existing, inflammatory lesion in the right psoas muscle (Fig. 3B). The patient was treated again with a third cycle of praziquantel therapy. After 4 days, the catheter for draining pleural fluid was removed, and she was discharged.

On the follow-up clinical visit, she received the fourth and fifth cycles of praziquantel therapy. Six months after the first admission, complete blood cell (CBC) revealed WBC count of 10,900 cells/mm3 and eosinophil proportion of 10.0%. A follow-up abdominal sonogram showed no abnormal lesions in the peritoneal cavity as well as an improvement in the omental lesion in the right lower quadrant (RLQ) of the abdomen. No other family members were ill, and their serum and stool samples tested negative for the infection. Following the fifth cycle of praziquantel therapy and pleural effusion drainage, all symptoms, including abdominal pain and tenderness in the right inguinal area, resolved, and the abnormal psoas muscle lesion also disappeared.

DISCUSSION

After the 1970s, the rate of infection and incidence of paragonimiasis decreased in many endemic countries. In South Korea, however, paragonimiasis persisted, and the major source of infection has been presumed to be soybean-sauced freshwater crabs (='Kejang'). In 1990, 11.8% of crabs purchased at markets in Seoul were positive with a mean of 2.1 metacercariae per positive crab [5-7]. In a recent study, the rate of infected crabs showed low frequency, but, only the crayfish collected at Haenam, Jeollanam-do, were positive for P. westermani metacercariae [12]. However, 'Kejang' is sold more in large cities than in rural areas, clinicians should include paragonimiasis as a possible diagnosis when the patient's chest radiograph shows pulmonary infiltration and peripheral blood eosinophilia even in metropolitan cities [13].

The major symptoms of paragonimiasis are cough, hemoptysis, and dyspnea; some of these overlap with symptoms of tuberculosis and other pulmonary disorders. Pulmonary infiltrates, effusion, nodules, or lesions are also very common [14, 15], and ectopic locations of flukes include the pleura, abdominal wall, viscera, and brain. In our case, the patient complained of abdominal pain, especially in the right flank and right inguinal area but had no cough, dyspnea, or chest pain. The chest radiograph revealed pleural effusion, and abdominal sonography showed a low-echoic lesion with inflammation of the surrounding fat in the psoas mucle. This lesion is presumed to be due to adult flukes, which are present in loosely formed cysts in the psoas muscle.

Diagnosis of paragonimiasis is established by detection of the characteristic eggs in the stool, tissues, sputum, or pleural fluid. In our case, Paragonimus eggs were not found in the stool, sputum, or pleural fluid. Instead, P. westermani-specific IgG antibody was detected in the serum by ELISA. It is well established that serologic testing for anti-Paragonimus IgG by ELISA has a sensitivity of 100% and a specificity of 91%-100% [8].

The recommended treatment for paragonimiasis is 25 mg/kg of praziquantel 3 times a day for 2 consecutive days [16]. Most papers have mentioned cure rates of around 90-100% using this regimen. However, recent studies have reported treatment failure after an initial cycle of praziquantel medication [17]. Radiographic abnormalities are shown to gradually improve over months; most resolving completely after 1 year [15]. Small pleural effusions generally clear with therapy, whereas larger effusions may require either thoracentesis or surgical decortications to prevent long-term pleural complications [18]. The degree of peripheral blood eosinophilia decreases when the disease shifts to its chronic phase. This chronicity of the disease could be a reason for the requirement of additional doses of praziquantel [4].

In the present case, the patient's CBC showed persistence of hypereosinophilia, and the chest radiograph revealed pleural effusion even after the first cycle of praziquantel. The patient improved after 5 cycles of praziquantel therapy and pleural fluid drainage. Last eosinophils (%) was 10.0%, which was still high; however, we surmised that this hypereosinophilia was due to allergic rhinitis and atopic dermatitis.

Paragonimiasis can be prevented easily. Public health education programs should warn people not to consume uncooked crabs or crayfish. The present case involved a girl who, after eating uncooked freshwater crabs, became infected with Paragonimus, but did not develop any respiratory symptoms. We, therefore, suggest that all patients presenting with eosinophilia, high levels of IgE antibody, and with a history of ingestion of uncooked crabs or crayfish, even without respiratory symptoms, should be evaluated for infection with Paragonimus sp.

References

- 1.Dainichi T, Nakahara T, Moroi Y, Urabe K, Koga T, Tanaka M, Nawa Y, Furue M. A case of cutaneous paragonimiasis with pleural effusion. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:699–702. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.2003.01892.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee SH, Chai JY, Hong ST. Synopsis of Medical Parasitology. Seoul, Korea: Korea Medical Publising Co; 1996. pp. 211–212. [Google Scholar]

- 3.DeFrain M, Hooker R. North American paragonimiasis: Case report of a severe clinical infection. Chest. 2002;121:1368–1372. doi: 10.1378/chest.121.4.1368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Choi DW. Paragonimus and paragonimiasis in Korea. Korean J Parasitol. 1990;28(suppl):79–102. doi: 10.3347/kjp.1990.28.suppl.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cho SY, Kang SY, Kong Y, Yang HJ. Metacercarial infections of Paragonimus westermani in freshwater crabs sold in markets in Seoul. Korean J Parasitol. 1991;29:189–191. doi: 10.3347/kjp.1991.29.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rim HJ, Lee JS, Chung HS, Hyun I, Jung KH. Epidemiological survey on paragonimiasis in Kang Hwa Gun. Korean J Parasitol. 1975;13:139–151. doi: 10.3347/kjp.1975.13.2.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hong YA, Joo CY, Pyun YS. Infestation status of Paragonimus westermani metacercariae in the second intermediate host in Ulchin county, Kyungpook Province. Korean J Parasitol. 1986;24:194–200. doi: 10.3347/kjp.1986.24.2.194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vidamaly S, Choumlivong K, Keolouangkhot V, Vannavong N, Kanpittaya J, Strobel M. Paragonimiasis: A common cause of persistent pleural effusion in Lao PDR. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2009;103:1019–1023. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2008.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Obara A, Nakamura-Uchiyama F, Hiromatsu K, Nawa Y. Paragonimiasis cases recently found among immigrants in Japan. Intern Med. 2004;43:388–392. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.43.388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mukae H, Taniguchi H, Matsumoto N, Iiboshi H, Ashitani J, Matsukura S, Nawa Y. Clinicoradiologic features of pleuropulmonary Paragonimus westermani on Kyusyu Island, Japan. Chest. 2001;120:514–520. doi: 10.1378/chest.120.2.514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cho SY, Hong ST, Rho YH, Choi SY, Han YC. Application of micro-ELISA in serodiagnosis of human paragonimiasis. Korean J Parasitol. 1981;19:151–156. doi: 10.3347/kjp.1981.19.2.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim EM, Kim JL, Choi SI, Lee SH, Hong ST. Infection status of freshwater crabs and crayfish with metacercariae of Paragonimus wertermani in Korea. Korean J Parasitol. 2009;47:425–426. doi: 10.3347/kjp.2009.47.4.425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sohn BS, Bae YJ, Cho YS, Moon HB, Kim TB. Three cases of paragonimiasis in a family. Korean J Parasitol. 2009;47:281–285. doi: 10.3347/kjp.2009.47.3.281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kagawa FT. Pulmonary paragonimiasis. Semin Respir Infect. 1997;12:149–158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boé DM, Schwarz MI. A 31-year-old man with chronic cough and hemoptysis. Chest. 2007;132:721–726. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-0712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Keiser J, Utzinger J. Food-borne trematodiases. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2009;22:466–483. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00012-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sumitani M, Mikawa T, Miki Y, Nisida K, Tochino Y, Kamimori T, Fujiwara H, Fujikawa T, Nakamura F. A case of chronic pleuritis by Paragonimus wetermani infection resistant to standard chemotherapy and cured by three additional cycles of chemotherapy. Nihon Kokyuki Gakkai Zasshi. 2005;43:427–431. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blair D, Xu ZB, Agatsuma T. Paragonimiasis and the genus Paragonimus. Adv Parasitol. 1999;42:113–222. doi: 10.1016/s0065-308x(08)60149-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]