Abstract

Purpose

Prior studies demonstrated that the effect of family-based economic empowerment intervention Suubi on reducing attitudes approving sexual risk taking among orphaned adolescents in Uganda. To understand mechanisms of change, the paper examines the effect of Suubi intervention on family support variables and their role in mediating the change in adolescents' attitudes toward sexual risk-taking.

Methods

The Suubi study utilized a cluster randomized experimental design with three waves and included 283 orphaned adolescents from 15 primary schools in Rakai, Uganda. First, using mixed effects models, the study tests for the effect of intervention on family support variables. Second, using mediation analysis, the study examines whether the change in sexual risk-taking attitudes was mediated by the change in family support.

Results

Compared to adolescents from the control group, at wave 2, adolescents in the treatment group reported higher levels of perceived support from caregivers, were more willing to talk to caregivers about their problems, and felt more comfortable talking about sexual risk behaviors with their caregivers. Mediation analysis demonstrated that the improvement in perceived support from caregivers at wave 2 accounted for 16.8% of the reduction in adolescents' attitudes toward sexual risk-taking at wave 3 (z = -2.21, p<.05).

Conclusions

A family-based economic empowerment intervention Suubi may have the potential to increase family support to orphaned adolescents. Interventions aimed at strengthening existing social networks and improving connectedness with surviving family members may be critical in preventing sexual risk-taking among orphaned adolescents in Uganda, which is characterized by low resources.

Keywords: family support, family communication, mediation analysis, attitudes toward sexual risk-taking, orphaned adolescents, Uganda, Suubi-Project, economic empowerment intervention, sub-Saharan Africa

Introduction

About 2.5 million children under the age of 17 in Uganda are orphans having lost one or both parents as defined by UNICEF [1]. An estimated 48% of these children are orphaned due to AIDS [1]. Orphaned adolescents in sub-Saharan Africa demonstrate higher sexual risk behaviors defined as early and unprotected sex [7] and are, therefore, at higher risk for early pregnancies, HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs), compared to non-orphans [2, 3].

Prior studies demonstrated that a family-based economic empowerment intervention Suubi had a positive effect on reducing orphaned adolescents' attitudes accepting sexual risk taking [4-6]. Attitudes approving early, unprotected, or forced sex [7] may serve as a proxy for future sexual risk behaviors among younger and sexually inactive youth [8]. To understand the mechanisms of the change process, and to be able to connect intervention components and outcomes, it is crucial to examine variables mediating behavioral change [9].

Resilience theory examining healthy behavior in the environment of risk exposure suggests that resources can balance the effects of risks and adversities [10, 11]. Resilience studies argue the positive role of resources and assets in helping adolescents to overcome consequences of risk exposure as well as to avoid negative trajectories associated with risk behaviors [10]. The Suubi intervention is positioned in asset theory suggesting that accumulation of assets produces “asset effects”[12] increasing adolescents' hopes and beliefs in their future and, thus, reduces their sexual risk-taking. Additionally, a positive relationship between the child and her/his caregiver can be an important resource playing a protective role and associated with reduced sexual risks among adolescents [13-16]. An ongoing caring relationship with an adult is one of the most important sources for resilience in children and can protect them from risk taking decisions when they experience stress and adversity [11]. The literature does not explain, however, the extent to which family support can reduce sexual risks specifically for orphaned youths in sub-Saharan Africa who are commonly cared for by extended family members [17].

Using a resilience theoretical framework—which suggests that resources can balance the effects of risks and adversities [10, 11]—this paper examines the role of family support as a mechanism through which the family-based economic empowerment program Suubi affects sexual risk-taking attitudes of orphaned adolescents. The paper aims to answer the following research questions:

Does family support change as a result of a family-based economic empowerment intervention Suubi?

Is there a relationship between the family support and orphaned adolescents' attitudes toward sexual risk taking?

Does family support play a mediating role in changing attitudes toward sexual risk-taking, as a primary outcome of the Suubi intervention?

Orphaned adolescents and sexual-risk taking

Studies suggest that orphaned adolescents are at a higher disposition for sexual risks compared to their non-orphan peers [2, 3]. A study of 1,694 South African youth found that 14-18 year-old orphans were 1.38 times more likely than non-orphans to have engaged in sex [2]. In Zimbabwe, a study of 15-18 year-old adolescents found no reported differences in the prevalence rates of HIV or STIs between orphaned and non-orphaned males. However, orphaned females were more likely than their non-orphan counterparts to report teenage pregnancy, experience STI symptoms and showed a higher prevalence of HIV [3]. In Uganda, a Sero-Behavioral Survey showed that more 15-17-year old orphaned females have had sex by age 15 compared to non-orphan females [18].

Adolescents from poor households are at an especially elevated risk for sexual risk-taking, including early onset of sexual intercourse and unprotected sex [19, 20]. Most of the households accommodating orphaned adolescents in rural Uganda are particularly susceptible to poverty due to loss of one or more income earners [21].

Family support as a protective factor in sexual risk-taking

Parents' importance in adolescents' socialization and protective role in influencing adolescents' sexual risk taking have been well documented [22]. Studies demonstrate that better quality of family relationships, including parental warmth, support, and connectedness between a child and his/her parent, is associated with lower engagement in sexual risk behaviors, including delayed onset of sexual activity [13-16]. Another important protective aspect of family support, and one that may be adversely affected by orphanhood, is parent-child communication. Adolescents with more frequent and open parent-child communication, including discussions about sexuality, have shown postponed sexual activity [23] and higher likelihood of condom use [24]. Orphaned adolescents, however, lack close parental support and supervision, which make them more susceptible to sexual risks [2, 25].

Family support for orphaned adolescents

In sub-Saharan Africa the growing number of orphaned youth are not able to count on the emotional and economic support of their caretakers, who are usually aging grandmothers overwhelmed and pre-occupied with the economic responsibility and demands of caring for and supporting these children [26].

Before the era of the HIV/AIDS pandemic, the “family unit” was the main social nucleus in most regions of Africa [27]. The family unit was the primary source of care and nurture and a crucial safety-net in times of hardship [21]. Unfortunately, the spread of HIV/AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa had detrimental effects on the family's role as the central support system [17]. Poverty accompanying the HIV/AIDS pandemic undermined not only a family's ability to physically care for children, but also their stability, functioning, and wellbeing [28]. As a result, a family's ability to provide quality care for orphaned children under their care was significantly compromised.

Based on the theory and literature review, we offer the following hypotheses:

Over time, participants in the Suubi intervention group will demonstrate stronger family support and improved family communication compared to participants in the control group;

Improvements in family support and family communication will be associated with the reduction in attitudes approving sexual risk taking behaviors;

Changes in family support and family communication will mediate the change in attitudes toward sexual risk-taking among adolescents impacted by the Suubi intervention.

Methods

Sample and study site

The paper uses data from the Suubi (Hope) study examining an economic empowerment model of care and support for orphaned adolescents within a family setting. The Suubi Project (2005-2008) was implemented in rural Rakai district of Uganda - the site of the first HIV infection in East Africa and one of the districts hardest hit by HIV/AIDS with a high number of AIDS orphaned youth [29]. We selected 15 geographically separatedpublic primary schools in Rakai District with comparable performance on national exams and similar socio-demographic composition of student body. The caregivers of orphaned adolescents at these schools had to contact the project team expressing their interest to participate in the project. Out of 289 screened adolescents, 283 met the inclusion criteria: (1) were between the ages 11 and 17, (2) had lost one or both parents to AIDS, and (3) were in the last two years of primary schooling [5, 6]. Adolescents and their primary caregivers provided informed consent separately to avoid possible coercion. The sample size at baseline included 146 participants in the control group and 137 participants in the treatment group (N=283). Due to attrition (2.1% at wave 2 and 7.4% at wave 3), the sample reduced to 256 participants at wave 3.

Study design and intervention

The study utilized a cluster randomized design. To minimize cross-arm contamination, randomization was conducted at the school level. Each of the fifteen schools was randomly assigned to either treatment or control condition. All participants within one school received the same condition assignment. Adolescents from the intervention and control conditions received the usual care for orphaned youth comprising of food aid (school lunches), scholastic materials (books and school supplies), counseling, and recreation activities such as sports, music and leisure activities. By virtue of being in school, all adolescents were exposed to a nationwide school-based curriculum on HIV prevention based on the ABC model (Abstinence, Be Faithful, and Only use a Condom if you must).

In addition to the usual care, adolescents and their primary caregivers in the intervention condition received Suubi intervention, which included: (1) a matched savings account for postprimary schooling; (2) twelve 1-hour workshops on financial education, asset-building, and future planning; and (3) monthly peer mentorship sessions for youth. The matched savings accounts held in the child's name were managed jointly by caregiver and the child, caregivers attended workshops jointly with their children, and any of the child's relatives were encouraged to contribute towards this account. Families in the intervention group saved, on average, USD$6.33 per month or USD$76 per year. After individual contributions were matched by the Suubi Project funds at a ratio 2:1 (with the match cap USD$10 per month per family), families on average accumulated USD$228 per year [5]. Uganda is one of 48 least developed countries, where this amount of money is substantial and sufficient to pay for two years of secondary public education. A detailed description of intervention is provided elsewhere (see [4-6]).

Measures

A 90-minute individual interview with adolescents was administered by an interviewer at the baseline (wave 1), 10-month follow-up (wave 2) and 20-month follow-up (wave 3). The questions were adapted from the Family Environment Scale / Family Assessment Measures (FES/FAM) scale [30] and instruments measuring youth attitudes toward sex [31]. All scales have been previously used in Africa with good psychometric properties [32]. Items for each scale are presented in Table 2.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics for sexual risk taking attitudes and family support and communication scales at baseline (N=283).

| Mean [95% Confidence Interval] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable (min-max) | Total | Control group | Treatment Group | Design-based F |

| OUTCOME VARIABLE | (N=283) | (n=146) | (n=137) | |

|

| ||||

| Sexual risk taking attitudes | 1.55 [1.35, 1.75] | 1.38 [1.2, 1.56] | 1.74 [1.51, 1.96] | 6.89* |

| It is OK for someone my age to have sex with someone they just met | 1.26 [1.14, 1.38] | 1.16 [1.07, 1.25] | 1.37 [1.16, 1.56] | 3.84 |

| It is OK for someone my age to have sex with someone they love | 1.92 [1.66, 2.17] | 1.85 [1.53, 2.17] | 1.99 [1.61, 2.36] | 0.33 |

| It is OK for someone my age to have premarital sex | 1.80 [1.35, 2.25] | 1.39 [1.17, 1.60] | 2.24 [1.63, 2.85] | 7.96* |

| It is OK to force girlfriend/boyfriend to have sex against their will | 1.28 [1.1, 1.46] | 1.1 [.99, 1.21] | 1.47 [1.24, 1.70] | 9.65** |

| It is OK to have sex without protection with someone you know | 1.51 [1.28, 1.74] | 1.45 [1.07, 1.83] | 1.57 [1.36, 1.79] | 0.37 |

|

| ||||

| MEDIATING VARIABLES | ||||

|

| ||||

| Perceived family support (min 1 – max 5) | 4.09 [4.0, 4.19] | 4.09 [4.01, 4.17] | 4.1 [3.92, 4.27] | 0.00 |

| Your parent/caregiver: | ||||

| Takes time to listen to you | 3.45 [3.33, 3.57] | 3.50 [3.41, 3.59] | 3.39 [3.19, 3.6] | 1.03 |

| Offers to help if you have a problem | 3.64 [3.52, 3.75] | 3.67 [3.59, 3.75] | 3.61 [3.39, 3.82] | 0.37 |

| Is available when needed | 4.15 [3.93, 4.36] | 4.26 [4.14, 4.37] | 4.03 [3.65, 4.41] | 1.50 |

| I tell my caregiver important things that happen to me | 4.21 [4.05, 4.37] | 4.30 [4.17, 4.43] | 4.12 [3.87, 4.36] | 2.12 |

| I let my caregiver know when I'm sad or upset | 3.32 [3.04, 3.6] | 2.99 [2.73, 3.24] | 3.67 [3.26, 4.08] | 9.29** |

| Helps me in practical ways | 4.06 [3.91, 4.21] | 4.01 [3.9, 4.13] | 4.11 [3.83, 4.39] | 0.45 |

| Makes me feel good about self | 4.57 [4.44, 4.69] | 4.63 [4.51, 4.74] | 4.5 [4.29, 4.71] | 1.23 |

| Is a good listener when I have problems | 4.49 [4.38, 4.61] | 4.5 [4.31, 4.68] | 4.49 [4.34, 4.63] | 0.00 |

| Often criticizes me | 2.18 [1.96, 2.41] | 2.25 [1.95, 2.55] | 2.12 [1.77, 2.46] | 0.30 |

| Has caused me a lot of problems | 1.27 [1.17, 1.36] | 1.28 [1.2, 1.35] | 1.26 [1.09, 1.42] | 0.06 |

| Helps me set rules for myself | 4.37 [4.24, 4.49] | 4.46 [4.35, 4.57] | 4.26 [4.08, 4.44] | 4.14 |

| Would help if I had problems in school | 4.33 [4.2, 4.46] | 4.32 [4.14, 4.49] | 4.34 [4.14, 4.55] | 0.04 |

| Family communication | ||||

| Family sexual risk communication, frequency (min 1 - max 4) | 2.15 [1.95, 2.35] | 2.13 [1.93, 2.33] | 2.17 [1.82, 2.51] | 0.04 |

| Parents talk about HIV/AIDS | 2.11 [1.88, 2.35] | 2.05 [1.76, 2.33] | 2.18 [1.85, 2.52] | .43 |

| Parents talk about having sex | 2.13 [1.91, 2.35] | 2.2 [1.98, 2.42] | 2.05 [1.65, 2.45] | .48 |

| Parents talk about STDs | 2.03 [1.85, 2.2] | 2.02 [1.81, 2.23] | 2.04 [1.76, 2.31] | .01 |

| Parents talk about bad friends | 2.36 [2.16, 2.57] | 2.32 [2.16, 2.48] | 2.41 [2.04, 2.78] | .21 |

| Parents talk about puberty | 2.10 [1.86, 2.35] | 2.06 [1.82, 2.3] | 2.15 [1.72, 2.58] | .16 |

| Family sexual risk communication, comfort level (min 1 - max 4) | 2.31 [1.96, 2.65] | 2.51 [2.0, 3.01] | 2.09 [1.62, 2.57] | 1.64 |

| Comfortable talking with parents about HIV/AIDS | 2.21 [1.86, 2.56] | 2.43 [1.94, 2.93] | 1.98 [1.49, 2.47] | 1.95 |

| Comfortable talking with parents about having sex | 2.17 1.82, 2.53] | 2.43 [1.91, 2.96] | 1.9 [1.45, 2.35] | 2.73 |

| Comfortable talking with parents about STDs | 2.24 [1.91, 2.56] | 2.46 [1.95, 2.96] | 2.0 [1.58, 2.42] | 2.27 |

| Comfortable talking with parents about bad friends | 2.4 [2.03, 2.78] | 2.55 [2.01, 3.08] | 2.25 [1.7, 2.8] | 0.70 |

| Comfortable talking with parents about puberty | 2.5 [2.15, 2.85] | 2.66 [2.18, 3.13] | 2.34 [1.81, 2.86] | 0.95 |

| Willingness to talk about problems (min 0 – max 3) | 2.46 [2.29, 2.63] | 2.51 [2.35, 2.68] | 2.4 [2.11, 2.69] | 0.52 |

| Would you talk about schoolwork? | 90.25 [84.34, 94.09] |

90.14 [86.31, 92.99] |

90.37 [76.63, 96.41] |

0.002 |

| Would you talk about boyfriend/girlfriend? | 75.45 [68.11, 81.56] |

77.46 [67.26, 85.19] |

73.33 [62.84, 81.73] |

0.46 |

| Would you talk about skipping school? | 80.14 [71.93, 86.41] |

83.0 [75.16, 88.87] |

77.04 [63.4, 86.66] |

1.01 |

p≤.05,

p≤.01,

p≤.001

Family support

Adolescents rated twelve items describing perceived support from caregivers on a 5-point scale (from ‘almost never’ to ‘almost always’). Two items in inverse direction were reverse-coded. An average score on the twelve items was created with higher value indicating higher level of perceived family support (α=.78).

Family communication

We measured two dimensions of family communication:

Family sexual risk communication included two subscales: frequency of conversations with caregiver about sex, HIV, STIs, and puberty; and level of comfort discussing these topics with caregiver. Both scales included five items and each item was measured on a 4-point scale (‘never’ to ‘a lot’ or ‘very uncomfortable’ to ‘very comfortable’, respectively). The average composite score was computed for both subscales with a higher score indicating a higher frequency (α=0.9) and a higher comfort level of family sexual risk communication (α=0.96).

Willingness to talk to caregivers about problems measure included three binary items. Positive answers were summed with a higher score indicating an adolescent's greater willingness to talk to his/her caregiver.

Attitudes toward sexual risk behaviors

Adolescents in this study reported low levels of sexual risk-taking behaviors. At Wave 3 less than 1 percent of youth participants (n=2) reported being sexually active. This could be due to young age of study participants as well as the social desirability bias common for interviewer-administered surveys [4, 6]. Indeed, collecting accurate information about sexual risk behaviors among youth in sub-Saharan African has been methodologically problematic [33]. Therefore, given the low levels of reported actual sexual risk-taking behaviors, this paper uses a measure of attitudes toward sexual risk behaviors as a proxy for actual sexual risk-taking behaviors. Studies indicate that attitudes to engage in sexual risk behaviors may be predictive of actual behaviors [8]. Outcome variable is a 5-item sexual risk attitudes scale with each statement rated on a 5-point scale from ‘disagree a lot’ to ‘agree a lot’. The average composite score has a moderate internal consistency (α=.58 at wave 1 and .7 at wave 2) and higher score indicates more approving sexual risk behaviors.

Socio-demographic measures included: youth participant's age, gender, religion and orphanhood type (double orphan, maternal orphan, and paternal orphan), type of male and female caregiver and primary caregiver's employment status.

Data analysis

Data analysis was performed in Stata 11. First, mixed-effects regression model approach was used to test for the effect of intervention on family support and family communication. The time by study group interaction served as a measure of intervention effect. The analysis accounted for clustering of individuals within schools and clustering of observations from three waves within individuals [34]. Models were adjusted for significant socio-demographic covariates.

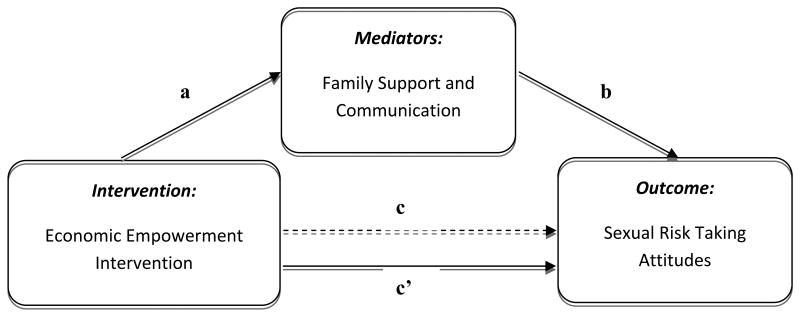

Second, using MacKinnon's approach to mediation analysis [35, 36], we examined whether changes in family support and family communication mediated the relationship between the Suubi intervention and changes in adolescents' attitudes toward sexual risk-taking as the intervention outcome (Figure 1). To account for the temporal factor, the difference in family support between wave 2 and wave 1 served as a measure of mediator and the difference in sexual risk-taking attitudes between wave 3 and wave 1 was used as a measure of outcome.

Figure 1.

Hypothesized mediation model between the family-based economic empowerment intervention Suubi and attitudes toward sexual risk-taking as its outcome.

The model described in Figure 1 includes the following:

a = direct effect of the Suubi intervention on perceived family support and family communication among orphaned adolescents;

b = direct effect of perceived family support and family communication on adolescents' sexual risk-taking attitudes;

c = total effect of intervention on outcome, including the direct effect of the intervention and indirect effect (through the mediator);

c' = effect of the Suubi intervention on adolescents' sexual risk-taking attitudes adjusting for the mediators -- perceived family support and family communication.

A total effect of the Suubi intervention on sexual risk-taking among adolescents was previously tested and demonstrated to be statistically significant [4]. If change in the outcome occurs through mediating variables, there will be a significant reduction in the effect of intervention in the presence of mediator (c'), compared to the total effect (c) [36]. Sobel's test was used to assess statistical significance of the mediating effect [37].

Results

Descriptive results

Table 1 presents information about socio-demographic characteristics of the sample. On average, participants were 13.7 years of age, 57% were girls and the majority was Christian. Over a third of participants reported having lost both biological parents. Along with surviving parent, extended family members (grandparents, aunts, uncles, and older siblings) were among key caregivers. There were no significant differences in the sample composition across waves.

Table 1. Descriptive characteristics of the sample at baseline.

| Percent, % [95% Confidence Interval] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Total (N=283) |

Control Group (n=146) |

Treatment Group (n=137) |

Design-based F |

| Age in years, mean | 13.71 [13.37, 14.05] | 13.6 [13.31, 13.89] | 13.82 [13.21, 14.42] | 0.47 |

| Female child | 56.89 [47.28,66.01] | 53.42 [43.05,63.51] | 60.58 [44.25,74.85] | 0.65 |

| Orphanhood status | 1.19 | |||

| Double orphan | 39.07 [33.41, 45.04] | 41.26 [32.44,50.67] | 36.76 [30.8,43.16] | |

| Maternal orphan | 19.0 [14.52, 24.45] | 16.08 [13.94,18.48] | 22.06 [14.21,32.59] | |

| Paternal orphan | 41.94 [36.45, 47.63] | 42.66 [33.05,52.86] | 41.18 [36.63,45.88] | |

| Religious affiliation | 0.62 | |||

| Christian (Catholic, Protestant, Born Again) | 92.58 [88.2, 95.42] | 91.1 [87.73, 93.61] | 94.16 [83.0, 98,16] | |

| Muslim | 7.42 [4.58, 11.8] | 8.9 [6.4, 12.27] | 5.84 [1.84, 17.0] | |

| Female caregiver | 0.53 | |||

| Biological mother | 39.58 [33.88, 45.57] | 36.99 [27.9, 47.09] | 42.34 [37.23, 47.62] | |

| Grandmother | 36.04 [28.71, 44.09] | 39.73 [28.03, 52.72] | 32.12 [25.1, 40.05] | |

| Other female relative (aunt, sister, step-mother) | 20.49 [15.67, 26.35] | 19.18 [12.62, 28.06] | 21.9 [15.64, 29.77] | |

| No female caregiver | 3.89 [1.81, 8.17] | 4.11 [1.9, 8.66] | 3.65 [.9, 13.66] | |

| Male caregiver | 4.98* | |||

| Biological father | 28.62 [22.87, 35.16] | 23.97 [20.18, 28.23] | 33.58 [24.62, 43.9] | |

| Grandfather | 13.78 [9.83, 18.99] | 12.33 [9.49, 15.87] | 15.33 [8.36, 26.42] | |

| Other male relative (uncle, brother, step-father) | 15.55 [12.45, 19.25] | 13.01 [10.53, 15.98] | 18.25 [13.78, 23.77] | |

| No male caregiver | 42.05 [35.6, 48.79] | 50.68 [47.56, 53.8] | 32.85 [26.57, 39.8] | |

| Employment status of primary caregiver | 4.51 | |||

| Self-employed | 62.99 [55.96, 69.51] | 68.75 [59.46, 76.74] | 56.93 [48.99, 64.54] | |

| Formally employed | 37.01 [30.49, 44.04] | 31.25 [23.26, 40.54] | 43.07 [35.46, 51.01] | |

At baseline, there were no significant differences between the treatment and control groups in the level of family support and communication (see Table 2). On average, adolescents reported moderate level of support from their caregivers and were willing to talk to them if faced with problems at school or in their personal lives. However, family sexual risk communication was rare and adolescents reported feeling uncomfortable talking about sexual topics with their caregivers.

Effect of the Suubi Intervention on Family Support and Family Communication

Table 3 shows the results of mixed effects models estimating the effect of Suubi intervention on family support and family communication variables. Compared to adolescents in the control group, adolescents in the treatment group reported significantly higher levels of perceived support from their caregivers at Wave 2 (B=.27, 95% CI=.12, .43).

Table 3. Mixed Effects Regression Models for Family Support and Family Communication across three waves.

| Explanatory Variables | Beta-coefficient (95 % Confidence Interval) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived family support | Family sexual risk communication (frequency) | Family sexual risk communication (comfort level) | Willingness to talk about problems | |

| Group assignment | ||||

| Control group | base | base | base | base |

| Treatment group | .01 [-.12, .14] | -.02 [-.35, .3] | -.57 [ -1.03, -.11]* | -.13 [-.35, .08] |

| Time | ||||

| Wave 1 | base | base | base | base |

| Wave 2 | -.1 [ -.22, .01] | .47 [.26, .68]*** | -.25 [-.49, -.01]* | .14 [-.01, .30] |

| Wave 3 | -.02 [ -.13, .1] | .37 [.15, .6]*** | -.23 [ -.5, .04] | -.08 [-.25, .09] |

| Group by Time Interaction | ||||

| Treatment group * Wave 2 | .27 [ .12, .43]*** | .22 [ -.07, .5] | .95 [.63, 1.28]*** | .23 [.01, .45]* |

| Treatment group * Wave 3 | .13 [ -.03, .29] | -.13 [ -.46, .19] | .60 [.24, .95]*** | .29 [.06, .53]* |

| Female child | .05 [ -.04, .14] | -.07 [ -.24, .11] | -.26 [ -.44, -.07]** | .30 [.19, .41]*** |

| Age in years | -.02 [-.05, .02] | .05 [ -.01, .12] | -.01 [-.07, .07] | -.01 [-.05, .03] |

| Orphanhood type | ||||

| Double orphan (both parents not living) | base | base | base | base |

| Maternal orphan (only mother not living) | -.12 [-.24, .01]† | -.18 [ -.42, .05] | -.01 [ -.26, .24] | .01 [-.15, .15] |

| Paternal orphan (only father is not living) | .05 [-.05, .14] | .06 [ -.12, .24] | .10 [-.10, .30] | -.08 [-.20, .04] |

| Constant | 4.29 [3.81, 4.77]*** | 1.5 [ .55, 2.45]** | 2.68 [1.61, 3.75]*** | 2.53 [1.91, 3.15]*** |

p≤.05,

p≤.01,

p≤.001

In regards to the frequency of family sexual risk communication, the main effect of time was significant at wave 2 and wave 3. However, the treatment group by time interaction was not statistically significant. This suggests that, over time, adolescents, regardless of their group assignment, talked more often about sexual risk taking with their caregivers.

However, compared to participants in the control group, participants in the treatment group reported feeling more comfortable talking about sexual risk behaviors with their caregivers and felt more willing to talk to caregivers about their problems both at wave 2 and wave 3. Compared to male adolescents, female adolescents were less comfortable with sexual risk communication, but were more willing to talk to their caregivers if faced with problems.

Mediation analysis

As illustrated by regression results in Table 4 (estimates a), assignment to Suubi treatment group was significantly associated with the change between wave 1 and wave 2 in perceived family support, comfort of family sexual risk communication and willingness to talk to caregivers. To meet one of the conditions of mediation analysis, the family support and family communication variables that changed significantly at wave 2 as a result of the Suubi intervention were further tested for the mediation effect.

Table 4.

Point estimates and standard errors (SEs) for mediation models assessing hypothesized processes of change of the Suubi intervention on adolescents' attitudes toward sexual risk-taking (N=256).

| Mediating Variables | Estimate a (SE) | Estimate b (SE) | Estimate c' (SE) | Estimate c (SE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family support | .28 (.08)*** | -.28 (.1)** | -.39 (.13)** | -.47 (.13)*** |

| Family sexual risk communication (frequency) | .24 (.15) | .09 (.05) | -.49 (.13)*** | -.47 (.13)*** |

| Family sexual risk communication (level of comfort) | .96 (.17)*** | .04 (.05) | -.50 (.14)*** | -.47 (.13)*** |

| Willingness to talk about problems | .26 (12)* | -.03 (.07) | -.46 (.13)*** | -.47 (.13)*** |

p≤.05,

p≤.01,

p≤.001

Further, we tested for the direct effect of mediating variables on sexual risk-taking attitudes (estimates b in Table 4). Estimates were significant only for family support variable suggesting that improvement in support from caregiver at wave 2 was associated with decreased sexual risk-taking attitudes at wave 3.

After adjusting for family support as the mediating factor, the magnitude of the Suubi intervention's effect on sexual risk-taking attitudes was reduced (c' estimates compared to estimate of the total effect c). The Sobel test demonstrated that the reduction in estimates was statistically significant (z = -2.21, p<.05). Thus, the mediation analysis showed that the improvement in perceived support from caregivers at wave 2 accounts for 16.8% of the total effect of Suubi intervention on reduction in attitudes toward sexual risk-taking among adolescents at wave 3. After the analysis was adjusted for participant's gender, age, and double orphanhood status, the mediation effect was reduced to 14.35% (z = 1.97, p<.05). In other words, as a result of the Suubi intervention, adolescents were less positive about engaging in sexual risk behaviors partially because they felt more connected and supported by their caregivers, which had also improved as a result of the Suubi intervention.

Discussion

The study indicates that in a low-resource country such as Uganda, where caregivers of orphaned adolescents are overwhelmed by the burden of financial hardship, a family-based economic empowerment intervention has the potential to strengthen family relations and facilitate caregiver support and guidance that orphaned adolescents need in order to succeed in their development and social adjustment. Probably, freed from worries of meeting basic financial needs—as a result of participating in an economic empowerment intervention—caregivers were able to find more time to be involved in the lives of the adolescents for whom they were caring. The findings demonstrate that orphaned adolescents whose families participated in Suubi intervention felt more emotionally connected to their caregivers, felt more comfortable communicating with them, and felt more supported by their caregivers. Notably, in families that were providing a caring and supportive environment to their orphaned adolescents, the youth became less approving of sexual risk-taking behaviors.

Our findings are in line with previous research illustrating that greater family support, including parents' warmth, involvement and connectedness with a child, is associated with reduced risk of sexual risk taking [15, 16]. This is particularly important because the ABC HIV prevention and sex education program introduced in the Ugandan school system focuses primarily on building knowledge around safe sex and fails to incorporate a child's family environment [38].

Given that all adolescents in the study were exposed to the national school-based HIV prevention curriculum and frequency of family sexual risk communication improved over time regardless of the group assignment. However, this change was not significantly associated with the reduced sexual risk taking attitudes. In economically impoverished and religiously traditional rural communities in Uganda, having conversations in the family about sex, HIV, STIs, and other issues related to risk behaviors may not be sufficient, if the family cannot provide the support and guidance to the adolescent.

Further, the study revealed that even with the devastation of family structures created by HIV/AIDS, traditional African family networks are important and can still be relatively strong in providing care for orphaned adolescents. Even when orphaned adolescents are unable to rely on support from their biological parents, extended family members can provide protective family environment and effectively moderate the hardships elevating orphaned adolescents' approval of sexual risk behaviors. In countries with inadequate state systems of social support, it is especially important to invest in strengthening traditional safety nets, such as extended families.

The results reinforce the importance of integrating the family component in programs aiming to reduce orphaned adolescents' vulnerability to sexual risk taking. There is strong support for intervening with families to mitigate youth's risk-taking [39, 40]. Family-based prevention programs should be targeted at developing better relationships between adolescents, caregivers, and other family members, and attempt to bolster protective family processes and influences by creating family-level economic empowerment opportunities for those caring for orphaned and vulnerable adolescents.

The study has a number of limitations. The interviewer-administered nature of the data collection method may have affected the responses and the social desirability bias may have limited the data on sexual risk behaviors and attitudes. Further, the sample did not include out-of-school orphaned adolescents or orphans from child-headed households. Therefore, the findings are limited to in-school orphaned adolescents residing with at least one adult caregiver. Additionally, the findings confine to rural population. We refrain from making inferences about urban population, which may have different family relationship patterns. The study is not sufficiently powered to examine differences in mediation effects between boys and girls, which should be explored in the future studies.

More research is needed to explore specific components of family support and youth-caregiver relationships using data both from adolescents and their caregivers and the pathways that explain their protective effects on sexual risk-taking behaviors. The research should investigate further the relationship between attitudes and actual sexual risk-taking behaviors and track those relationships over time. Finally, it is important to explore and understand cultural and contextual factors such as gender norms, intergenerational family structure, and early marriages, affecting family support and sexual risks among orphaned youth.

Conclusions

A family-based economic empowerment intervention has the potential to strengthen family support available to orphaned adolescents. This has important programming and practice implications, especially given the increasing number of orphaned children in sub-Saharan Africa and the need for best practices in supporting and caring for such children and adolescents. Interventions strengthening existing social networks and improving connectedness with surviving family members are critical in reducing orphaned adolescents' vulnerability to sexual risk taking in low-resource communities.

Human Participant Protection

The study was approved by Columbia University Institutional Review Board (IRB #AAA5337) and Uganda National Council of Science and Technology (SS 1540). The study protocol is registered in the ClinicalTrial.Gov database (ID: NCT01163695).

Acknowledgments

Financial support for the Suubi-Uganda Research Project was primarily provided by the National Institute of Mental Health (R21 MH076475-01, Fred M. Ssewamala, Principal investigator). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Mental Health or the National Institutes of Health. Our thanks to co-investigators Professors Mary McKay (at Mt. Sinai School of Medicine) and Jane Waldfogel (at Columbia University); and to the Suubi Project staff in Rakai District (Uganda), especially to Ms. Proscovia Nabunya and Reverend Fr. Kato Bakulu for coordinating the study activities in Uganda. Our special thanks to the children and caregivers who participated in the study.

Footnotes

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Leyla Ismayilova, Associate Research Scientist, Columbia University School of Social Work.

Fred M. Ssewamala, Email: fs2114@columbia.edu, Associate Professor of Social Work and International Affairs, Columbia University.

Leyla Karimli, Email: lk2404@columbia.edu, Ph.D. Student, Columbia University School of Social Work.

References

- 1.UNICEF. State of the World's Children 2009: Maternal and Newborn Health. United Nations Children's Fund [UNICEF]; New York: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thurman TR, et al. Sexual risk behavior among South African adolescents: is orphan status a factor? AIDS Behav. 2006;10(6):627–35. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9104-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gregson S, et al. HIV infection and reproductive health in teenage women orphaned and made vulnerable by AIDS in Zimbabwe. AIDS care. 2005;17(7):785–794. doi: 10.1080/09540120500258029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ssewamala FM, et al. Effect of economic assets on sexual risk-taking intentions among orphaned adolescents in Uganda. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100(3):483–8. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.158840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ssewamala FM, Ismayilova L. Integrating children's savings accounts in the care and support of orphaned adolescents in rural Uganda. Social Service Review. 2009;83(3):453–472. doi: 10.1086/605941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ssewamala FM, et al. Gender and the effects of an economic empowerment program on attitudes toward sexual risk-taking among AIDS-orphaned adolescent youth in Uganda. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2010;46(4):372–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Slonim-Nevo V, Ozawa M, Auslander W. Knowledge, attitudes and behaviors related to AIDS among youth in residential centers: results from an exploratory study. Journal of adolescence. 1991;14(1):17–33. doi: 10.1016/0140-1971(91)90043-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Terry D, Galligan R, Conway V. The prediction of safe sex behaviour: The role of intentions, attitudes, norms and control beliefs. Psychology & Health. 1993;8(5):355–368. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kraemer H, et al. Mediators and moderators of treatment effects in randomized clinical trials. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2002;59(10):877. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.10.877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fergus S, Zimmerman MA. Adolescent resilience: a framework for understanding healthy development in the face of risk. Annu Rev Public Health. 2005;26:399–419. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Walsh F. Family resilience: A framework for clinical practice. Family Process. 2003;42(1):1–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2003.00001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schreiner M, Sherraden MW. Can the Poor Save?: Saving & Asset Building in Individual Development Accounts. New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Buhi E, Goodson P. Predictors of adolescent sexual behavior and intention: A theory-guided systematic review. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2007;40(1):4–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McNeely C, et al. Mothers' influence on the timing of first sex among 14-and 15-year-olds. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2002;31(3):256–265. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(02)00350-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pearson J, Muller C, Frisco M. Parental involvement, family structure, and adolescent sexual decision making. Sociological Perspectives. 2006;49(1):67–90. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rose A, et al. The influence of primary caregivers on the sexual behavior of early adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2005;37(2):135–144. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Foster G. Safety nets for children affected by HIV/AIDS in southern Africa. A generation at risk. 2004:65–92. [Google Scholar]

- 18.MOH and ORC Macro. Uganda HIV/AIDS Sero-behavioural Survey 2004-2005. Ministry of Health MOH [Uganda] and ORC Macro; Calverton, Maryland, USA: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Madise N, Zulu E, Ciera J. Is poverty a driver for risky sexual behaviour? Evidence from national surveys of adolescents in four African countries. African journal of reproductive health. 2007;11(3):83–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Twa-Twa J. The role of the environment in the sexual activity of school students in Tororo and Pallisa districts of Uganda. 2004 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Foster G. The capacity of the extended family safety net for orphans in Africa. Psychology, Health & Medicine. 2000;5(1):55–62. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Perrino T, et al. The role of families in adolescent HIV prevention: A review. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2000;3(2):81–96. doi: 10.1023/a:1009571518900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Karofsky P, Zeng L, Kosorok M. Relationship between adolescent-parental communication and initiation of first intercourse by adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2001;28(1):41–45. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(00)00156-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Whitaker D, Miller K. Parent-adolescent discussions about sex and condoms: Impact on peer influences of sexual risk behavior. Journal of Adolescent Research. 2000;15(2):251. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nyambedha EO, Wandibba S, Aagaard-Hansen J. Changing patterns of orphan care due to the HIV epidemic in western Kenya. Soc Sci Med. 2003;57(2):301–11. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00359-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abebe T, Aase A. Children, AIDS and the politics of orphan care in Ethiopia: the extended family revisited. Soc Sci Med. 2007;64(10):2058–69. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ankrah EM. The impact of HIV/AIDS on the family and other significant relationships: the African clan revisited. AIDS Care. 1993;5(1):5–22. doi: 10.1080/09540129308258580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matshalaga N, Powell G. Mass orphanhood in the era of HIV/AIDS. British Medical Journal. 2002;324(7331):185. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7331.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Serwadda D, et al. Slim disease: a new disease in Uganda and its association with HTLV-III infection. The Lancet. 1985;326(8460):849–852. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(85)90122-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tolan P, et al. Evaluating process in child and family interventions: Aggression prevention as an example. Journal of Family Psychology. 2002;16(2):220–236. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.16.2.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Levy S, et al. Young adolescent attitudes toward sex and substance use: implications for AIDS prevention. AIDS Education and Prevention. 1993;5(4):340–351. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bhana A, et al. Children and youth at risk: Adaptation and pilot study of the CHAMP (Amaqhawe) programme in South Africa. African Journal of AIDS Research. 2004;3(1):33–41. doi: 10.2989/16085900409490316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mensch B, Hewett P, Erulkar A. The reporting of sensitive behavior by adolescents: a methodological experiment in Kenya. Demography. 2003;40(2):247–268. doi: 10.1353/dem.2003.0017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Raudenbush S, Bryk A. Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods. Sage Publications, Inc.; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 35.MacKinnon D. Introduction to statistical mediation analysis. Erlbaum Psych Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 36.MacKinnon D, Fairchild A, Fritz M. Mediation analysis. Annual Review of Psychology. 2007;58:593–614. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sobel M. Asymptotic confidence intervals for indirect effects in structural equation models. Sociological methodology. 1982:290–312. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Parikh SA. The political economy of marriage and HIV: the ABC approach, “safe” infidelity, and managing moral risk in Uganda. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(7):1198–208. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.088682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Donenberg G, Paikoff R, Pequegnat W. Introduction to the special section on families, youth, and HIV: Family-based intervention studies. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2006;31(9):869. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsj102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pequegnat W, Szapocznik J. Working with families in the era of HIV/AIDS. Sage Publications, Inc.; 2000. [Google Scholar]