Abstract

Eusociality, in which some individuals reduce their own lifetime reproductive potential to raise the offspring of others, underlies the most advanced forms of social organization and the ecologically dominant role of social insects and humans. For the past four decades kin selection theory, based on the concept of inclusive fitness, has been the major theoretical attempt to explain the evolution of eusociality. Here we show the limitations of this approach. We argue that standard natural selection theory in the context of precise models of population structure represents a simpler and superior approach, allows the evaluation of multiple competing hypotheses, and provides an exact framework for interpreting empirical observations.

For most of the past half century, much of sociobiological theory has focused on the phenomenon called eusociality, where adult members are divided into reproductive and (partially) nonreproductive castes and the latter care for the young. How can genetically prescribed selfless behavior arise by natural selection, which is seemingly its antithesis? This problem has vexed biologists since Darwin, who in The Origin of Species declared the paradox—in particular displayed by ants—to be the most important challenge to his theory. The solution offered by the master naturalist was to regard the sterile worker caste as a “well-flavored vegetable,” and the queen as the plant that produced it. Thus, he said, the whole colony is the unit of selection.

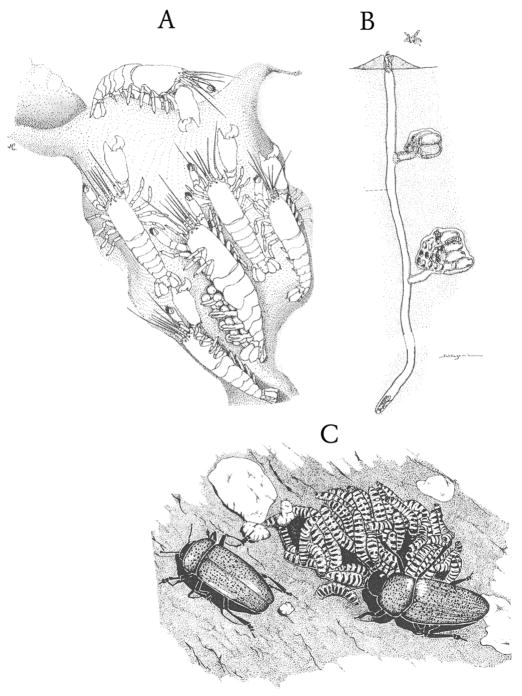

Modern students of collateral altruism have followed Darwin in continuing to focus on ants, honeybees, and other eusocial insects, because the colonies of most of their species are divided unambiguously into different castes. Moreover, eusociality is not a marginal phenomenon in the living world. The biomass of ants alone composes more than half that of all insects and exceeds that of all terrestrial nonhuman vertebrates combined1. Humans, which can be loosely characterized as eusocial2, are dominant among the land vertebrates. The “superorganisms” emerging from eusociality are often bizarre in their constitution, and represent a distinct level of biological organization (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. The ultimate superorganisms.

The gigantic queens of the leafcutter ants, one of whom (upper panel) is shown here, attended by some of her millions of daughter workers. Differences in size and labor specialization allows the ants to cut and gather leaf fragments (middle panel), and convert the fragments into gardens to grow fungi (lower panel). The species shown are respectively, top to bottom, Atta vollenweideri, A. sexdens, and A. cephalotes. (Photos by Bert Hölldobler.)

The rise and fall of inclusive fitness theory

For the past four decades kin selection theory has had a profound effect on the interpretation of the genetic evolution of eusociality and, by extension, of social behavior in general. The defining feature of kin selection theory is the concept of inclusive fitness. When evaluating an action, inclusive fitness is defined as the sum of the effect of this action on the actor’s own fitness and on the fitness of the recipient multiplied by the relatedness between actor and recipient, where “recipient” refers to anyone whose fitness is modified by the action.

The idea was first stated by J. B. S. Haldane in 1955, and a foundation of a full theory3 was laid out by W. D. Hamilton in 1964. The pivotal idea expressed by both writers was formalized by Hamilton as the inequality R > c/b, meaning that cooperation is favored by natural selection if relatedness is greater than the cost to benefit ratio. The relatedness parameter R was originally expressed as the fraction of the genes shared between the altruist and the recipient due to their common descent, hence the likelihood the altruistic gene will be shared. For example, altruism will evolve if the benefit to a brother or sister is greater than 2 times the cost to the altruist (R = 1/2) or 8 times in case of a first cousin (R = 1/8).

Due to its originality and seeming explanatory power, kin selection came to be widely accepted as a cornerstone of sociobiological theory. Yet it was not the concept itself in its abstract form that first earned favor, but the consequence suggested by Hamilton that came to be called the “haplodiploid hypothesis.” Haplodiploidy is the sex-determining mechanism in which fertilized eggs become females, and unfertilized eggs males. As a result, sisters are more closely related to one another (R = 3/4) than daughters are to their mothers (R = 1/2). Haplodiploidy happens to be the method of sex determination in the Hymenoptera, the order of ants, bees, and wasps. Therefore, colonies of altruistic individuals might, due to kin selection, evolve more frequently in hymenopterans than clades that have diplodiploid sex determination.

In the 1960s and 1970s, almost all the clades known to have evolved eusociality were in the Hymenoptera. Thus the haplodiploid hypothesis appeared to be supported, at least at first. The belief that haplodiploidy and eusociality are causally linked became standard textbook fare. The reasoning seemed compelling and even Newtonian in concept, traveling in logical steps from a general principle to a widely distributed evolutionary outcome4,5. It lent credence to a rapidly developing superstructure of sociobiological theory based on the presumed key role of kin selection.

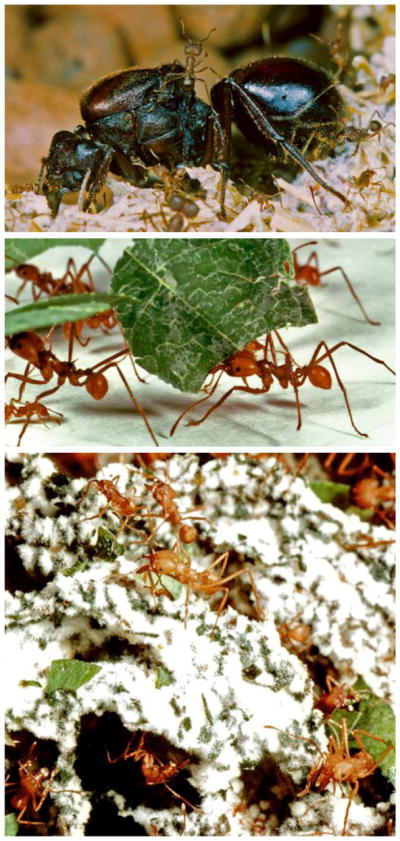

By the 1990s, however, the haplodiploid hypothesis began to fail. The termites had never fitted this model of explanation. Then more eusocial species were discovered that use diplodiploid rather than haplodiploid sex determination. They included a species of platypodid ambrosia beetles, several independent lines of Synalpheus sponge-dwelling shrimp (Fig. 2) and bathyergid mole rats. The association between haplodiploidy and eusociality fell below statistical significance. As a result the haplodiploid hypothesis was in time abandoned by researchers on social insects6–8.

Figure 2. Species on either side of the eusociality threshold.

A. A colony of a primitively eusocial Synalpheus snapping shrimp, occupying a cavity excavated in a sponge. The large queen (reproductive member) is supported by her family of workers, one of whom guards the nest entrance (from Duffy59). B. A colony of the primitively eusocial halictid bee Lasioglossum duplex, which has excavated a nest in the soil (from Sakagami and Hayashida60). C. Adult erotyid beetles of the genus Pselaphacus leading their larvae to fungal food (from Costa9); this level of parental care is widespread among insects and other arthropods, but has never been known to give rise to eusociality. These three examples illustrate the principle that the origin of eusociality requires the preadaptation of a constructed and guarded nest site.

Although the failure of the hypothesis was not by itself considered fatal to inclusive fitness theory, additional kinds of evidence began to accumulate that were unfavorable to the basic idea that relatedness is a driving force for the emergence of eusociality. One is the rarity of eusociality in evolution, and its odd distribution through the Animal Kingdom. Vast numbers of living species, spread across the major taxonomic groups, use either haplodiploid sex determination or clonal reproduction, with the latter yielding the highest possible degree of pedigree relatedness, yet with only one major group, the gall-making aphids, known to have achieved eusociality. For example, among the 70,000 or so known parasitoid and other apocritan Hymenoptera, all of which are haplodiploid, no eusocial species has been found. Nor has a single example come to light from among the 4,000 known hymenopteran sawflies and horntails, even though their larvae often form dense, cooperative aggregations6,9.

It has further turned out that selection forces exist in groups that diminish the advantage of close collateral kinship. They include the favoring of raised genetic variability by colony-level selection in the ants Pogonomyrmex occidentalis10 and Acromyrmex echinatior11—due, at least in the latter, to disease resistance. The contribution of genetic diversity to disease resistance at the colony level has moreover been established definitively in honeybees. Countervailing forces also include variability in predisposition to worker subcastes in P. badius, which may sharpen division of labor and improve colony fitness—although that hypothesis is yet to be tested12. Further, an increase in stability of nest temperature with genetic diversity has been found within nests of honeybees13 and Formica ants14. Other selection forces working against the binding role of close pedigree kinship are the disruptive impact of nepotism within colonies, and the overall negative effects associated with inbreeding15. Most of these countervailing forces act through group selection or, for eusocial insects in particular, through between-colony selection.

During its long history, inclusive fitness theory has stimulated countless measures of pedigree kinship and made them routine in sociobiology. It has supplied hypothetical explanations of phenomena such as the perturbations of colony investment ratios in male and female reproductives, and conflict and resolution of conflict among colony members. It has stimulated many correlative studies in the field and laboratory that indirectly suggest the influence of kin selection.

Yet, considering its position for four decades as the dominant paradigm in the theoretical study of eusociality, the production of inclusive fitness theory must be considered meager. During the same period, in contrast, empirical research on eusocial organisms has flourished, revealing the rich details of caste, communication, colony life cycles, and other phenomena at both the individual-selection and colony-selection levels. In some cases social behavior has been causally linked through all the levels of biological organization from molecule to ecosystem. Almost none of this progress has been stimulated or advanced by inclusive fitness theory, which has evolved into an abstract enterprise largely on its own16.

Foundational weakness of inclusive fitness theory

Many empiricists, who measure genetic relatedness and use inclusive fitness arguments, think that they are placing their considerations on a solid theoretical foundation. This is not the case. Inclusive fitness theory is a particular mathematical approach that has many limitations. It is not a general theory of evolution. It does not describe evolutionary dynamics nor distributions of gene frequencies17–19. But one of the questions that can be addressed by inclusive fitness theory is the following: which of two strategies is more abundant on average in the stationary distribution of an evolutionary process? Here we show that even for studying this particular question, the use of inclusive fitness requires stringent assumptions, which are unlikely to be fulfilled by any given empirical system.

In the online material (Part A) we outline a general mathematical approach based on standard natural selection theory to derive a condition for one behavioral strategy to be favored over another. This condition holds for any mutation rate and any intensity of selection. Then we move to the limit of weak selection, which is required by inclusive fitness theory17,20–22. Here all individuals have approximately the same fitness and both strategies are roughly equally abundant. For weak selection, we derive the general answer provided by standard natural selection theory, and we show that further limiting assumptions are needed for inclusive fitness theory to be formulated in an exact manner.

First, for inclusive fitness theory all interactions must be additive and pairwise. This limitation excludes most evolutionary games that have synergistic effects or where more than two players are involved23. Many tasks in an insect colony, for example, require the simultaneous cooperation of more than two individuals, and synergistic effects are easily demonstrated.

Second, inclusive fitness theory can only deal with very special population structures. It can describe either static structures or dynamic ones, but in the latter case there must be global updating and binary interactions. Global updating means that any two individuals compete uniformly for reproduction regardless of their (spatial) distance. Binary interaction means that any two individuals either interact or they do not, but there cannot be continuously varying intensities of interaction.

These particular mathematical assumptions, which are easily violated in nature, are needed for the formulation of inclusive fitness theory. If these assumptions do not hold, then inclusive fitness either cannot be defined or does not give the right criterion for what is favored by natural selection.

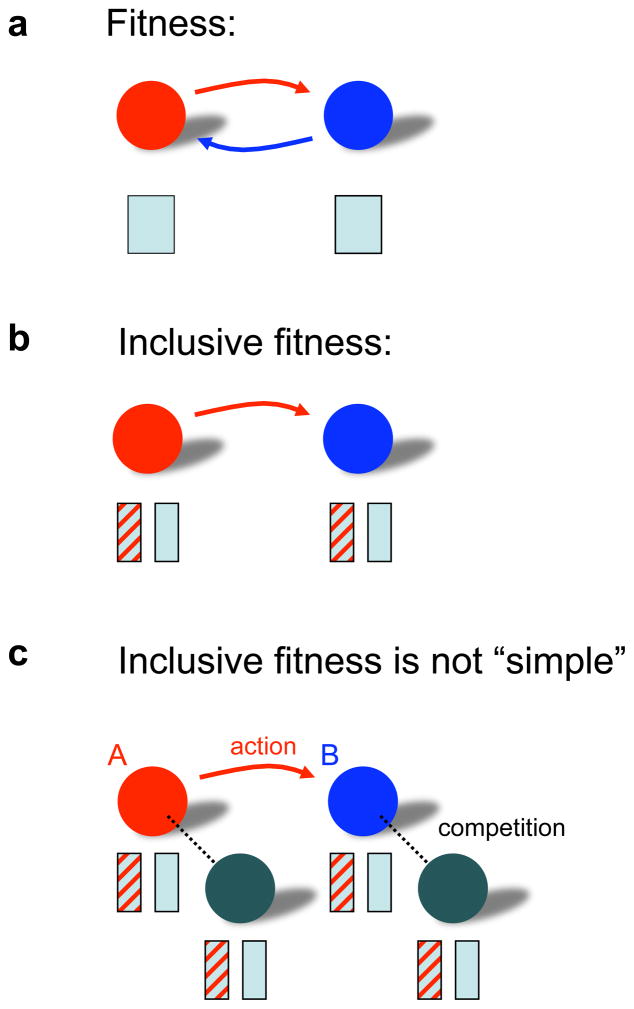

We also prove the following result: if we are in the limited world where inclusive fitness theory works, then the inclusive fitness condition is identical to the condition derived by standard natural selection theory. The exercise of calculating inclusive fitness does not provide any additional biological insight. Inclusive fitness is just another way of accounting3,20,24, but one that is less general (Fig 3).

Figure 3. The limitation of inclusive fitness.

A. The standard approach of evolutionary dynamics takes into account the relevant interactions and then calculates the fitness of each individual. B. The inclusive fitness of an individual is the sum of how the action of that individual affects its own fitness plus that of any other individuals multiplied by relatedness. Inclusive fitness theory is based on the very limiting assumption that the fitness of each individual can be broken down into additive components caused by individual actions. This is not possible in general. C. For calculating inclusive fitness one has to keep track of all competitive interactions that occur in the population. Here A acts on B changing its payoff and fitness. If A or B compete with other individuals, then their fitness values are also affected by A’s action, although no action is directed towards them. Inclusive fitness theory is not a simplification over the standard approach. It is an alternative accounting method, but one that works only in a very limited domain. Whenever inclusive fitness does work, the results are identical to those of the standard approach. Inclusive fitness theory is an unnecessary detour, which does not provide additional insight or information.

The question arises: if we have a theory that works for all cases (standard natural selection theory) and a theory that works only for a small subset of cases (inclusive fitness theory), and if for this subset the two theories lead to identical conditions, then why not stay with the general theory? The question is pressing, because inclusive fitness theory is provably correct only for a small (non-generic) subset of evolutionary models, but the intuition it provides is mistakenly embraced as generally correct25.

Sometimes it is argued that inclusive fitness considerations provide an intuitive guidance for understanding empirical data in the absence of an actual model of population genetics. However, as we show in the online material, inclusive fitness arguments without a fully specified model are misleading. It is possible to consider situations where all measures of relatedness are identical, yet cooperation is favored in one case, but not in the other. Conversely, two populations can have relatedness measures on the opposite ends of the spectrum and yet both structures are equally unable to support evolution of cooperation. Hence, relatedness measurements without a meaningful theory are difficult to interpret.

Another commonly held misconception is that inclusive fitness calculations are simpler than the standard approach. This is not the case; wherever inclusive fitness works, the two theories are identical and require the measurement of the same quantities. The impression that inclusive fitness is simpler arises from a misunderstanding of which effects are relevant: the inclusive fitness formula contains all individuals whose fitness is affected by an action, not only those whose payoff is changed (Fig 3c).

Hamilton’s rule almost never holds

Inclusive fitness theory often attempts to derive Hamilton’s rule, but finds it increasingly difficult to do so. In a simplified Prisoner’s Dilemma the interaction between cooperators and defectors is described in terms of cost and benefit. For many models we find that cooperators are favored over defectors for weak selection, if a condition holds that is of the form26–31:

| (1) |

This result is a straightforward consequence of the linearity introduced by weak selection32 and has nothing to do with inclusive fitness considerations.

Inequality (1) is Hamilton’s rule if “something” turns out to be relatedness, R. In inclusive fitness theory we have R = (Q−Q̄)/(1−Q̄), where Q is the average relatedness of two individuals who interact, while Q̄ is the average relatedness in the population. If we are in a scenario where inclusive fitness theory works, then an inclusive fitness calculation might derive inequality (1), but typically find that “something” is not relatedness. This fact, which is often obfuscated, is already the case for the simplest possible spatial models33,34. Therefore, even in the limited domain of inclusive fitness theory, Hamilton’s rule does not hold in general.

Are there empirical tests of inclusive fitness theory?

Advocates of inclusive fitness theory claim that many empirical studies support their theory. But often the connection that is made between data and theory is superficial. For testing the usefulness of inclusive fitness theory it is not enough to obtain data on genetic relatedness and then look for correlations with social behavior. Instead one has to perform an inclusive fitness type calculation for the scenario that is being considered and then measure each quantity that appears in the inclusive fitness formula. Such a test has never been performed.

For testing predictions of inclusive fitness theory, another complication arises. Inclusive fitness theory is only another method of accounting, one that works for very restrictive scenarios and where it works it makes the same predictions as standard natural selection theory. Hence, there are no predictions that are specific to inclusive fitness theory.

In part B of the online material we discuss some studies, which explore the role of kinship in social evolution. We argue that the narrow focus on relatedness often fails to characterize the underlying biology and prevents the development of multiple competing hypotheses.

An alternative theory of eusocial evolution

The first step in the origin of animal eusociality is the formation of groups within a freely mixing population. There are many ways in which this can occur35–43. Groups can assemble when nest sites or food sources on which a species is specialized are local in distribution; or when parents and offspring stay together; or when migratory columns branch repeatedly before settling; or when flocks follow leaders to known feeding grounds; or even randomly by mutual local attraction. A group can be pulled together when cooperation among unrelated members proves beneficial to them, whether by simple reciprocity or by mutualistic synergism or manipulation44.

The way in which groups are formed, and not simply their existence, likely has a profound effect on attainment of the next stage. What counts then is the cohesion and persistence of the group. For example, all of the clades known with primitively eusocial species surviving (in aculeate wasps, halictine and xylocopine bees, sponge-nesting shrimp, termopsid termites, colonial aphids and thrips, ambrosia beetles, and naked mole rats) have colonies that have built and occupied defensible nests6 (Fig. 2). In a few cases, unrelated individuals join forces to create the little fortresses. Unrelated colonies of Zootermopsis angusticollis, for example, fuse to form a supercolony with a single royal pair through repeated episodes of combat45. In most cases of animal eusociality, the colony is begun by a single inseminated queen (Hymenoptera) or pair (others). In all cases, however, regardless of its manner of founding, the colony grows by the addition of offspring that serve as nonreproductive workers. Inclusive fitness theorists have pointed to resulting close pedigree relatedness as evidence for the key role of kin selection in the origin of eusociality, but as argued here and elsewhere46,47, relatedness is better explained as the consequence rather than the cause of eusociality.

Grouping by family can hasten the spread of eusocial alleles, but it is not a causative agent. The causative agent is the advantage of a defensible nest, especially one both expensive to make and within reach of adequate food.

The second stage is the accumulation of other traits that make the change to eusociality more likely. All these preadaptations arise in the same manner as constructing a defensible nest by the solitary ancestor, by individual-level selection, with no anticipation of a potential future role in the origin of eusociality. They are products of adaptive radiation, in which species split and spread into different niches. In the process some species are more likely than others to acquire potent preadaptations. The theory of this stage is, in other words, the theory of adaptive radiation.

Preadaptations in addition to nest construction have become especially clear in the Hymenoptera. One is the propensity, documented in solitary bees, to behave like eusocial bees when forced together experimentally. In Ceratina and Lasioglossum, the coerced partners proceed variously to divide labor in foraging, tunneling, and guarding48–50. Furthermore, in at least two species of Lasioglossum, females engage in leading by one bee and following by the other bee, a trait that characterizes primitively eusocial bees. The division of labor appears to be the result of a preexisting behavioral ground plan, in which solitary individuals tend to move from one task to another only after the first is completed. In eusocial species, the algorithm is readily transferred to the avoidance of a job already being filled by another colony member. It is evident that bees, and also wasps, are springloaded, that is, strongly predisposed with a trigger, for a rapid shift to eusociality, once natural selection favors the change51–53.

The results of the forced-group experiments fit the fixed-threshold model proposed for the emergence of the phenomenon in established insect societies54,55. This model posits that variation, sometimes genetic in origin among individual colony members and sometimes purely phenotypic, exists in the response thresholds associated with different tasks. When two or more colony members interact, those with the lowest thresholds are first to undertake a task at hand. The activity inhibits their partners, who are then more likely to move on to whatever other tasks are available.

Another hymenopteran preadaptation is progressive provisioning. The first evolutionary stage in nest-based parental care is mass provisioning, in which the female builds a nest, places enough paralyzed prey in it to rear a single offspring, lays an egg on the prey, seals the nest, and moves on to construct another nest. In progressive provisioning the female builds a nest, lays an egg in it, then feeds or at least guards the hatching larva repeatedly until it matures (Fig 4a).

Figure 4. Solitary and primitively eusocial waps.

A. Progressive provisioning in a solitary wasp. Cutaway view of a nest showing a female Synagris cornuta feeding her larva with a fragment of caterpillar. An ichneumonid wasp and parasite Osprynchotus violator lurks on the outside of the nest (from Cowan61) waiting for the right moment to attack the larva. B. A colony of the primitively eusocial wasp Polistes crinitus. Its workers, working together are able simultaneously to guard the nest, forage for food, and attend the larvae sequestered in the nest cells. (Photo by Robert Jeanne.)

The third phase in evolution is the origin of the eusocial alleles, whether by mutation or recombination. In preadapted hymenopterans, this event can occur as a single mutation. Further, the mutation need not prescribe the construction of a novel behavior. It need simply cancel an old one. Crossing the threshold to eusociality requires only that a female and her adult offspring do not disperse to start new, individual nests but instead remain at the old nest. At this point, if environmental selection pressures are strong enough, the springloaded preadaptations kick in and the group commences cooperative interactions that make it a eusocial colony (Fig 4b).

Eusocial genes have not yet been identified, but at least two other genes (or small ensembles of genes) are known that prescribe major changes in social traits by silencing mutations in preexisting traits. More than 110 million years ago the earliest ants, or their immediate wasp ancestors, altered the genetically based regulatory network of wing development in such a way that some of the genes could be turned off under particular influence of the diet or some other environmental factor. Thus was born the wingless worker caste56. In a second example, discovered in the fire ant Solenopsis invicta, new variants of the major gene Gp-9 greatly reduce or remove the ability of workers to recognize aliens from other colonies, as well as the ability to discriminate among fertile queens. The resulting “microgyne” strain forms dense, continuous supercolonies that have spread over much of the species range in the southern United States57.

These examples, and the promise they offer of improved theory and genetic analysis, bring us to the fourth phase in the evolution of animal eusociality. As soon as the parents and subordinate offspring remain at the nest, natural selection targets the emergent traits created by the interactions of colony members.

By focusing on the emergent traits, it is possible to envision a new mode of theoretical research. It is notable that the different roles of the reproducing parents and their nonreproductive offspring are not genetically determined. They are products of the same genes or ensembles of genes that have phenotypes programmed to be flexible58. As evidence from primitively eusocial species has shown, they are products of representative alternative phenotypes of the same genotype, at least that pertaining to caste. In other words, the queen and her worker have the same genes that prescribe caste and division of labor, but they may differ freely in other genes. This circumstance lends credence to the view that the colony can be viewed as an individual, or “superorganism”. Further, insofar as social behavior is concerned, descent is from queen to queen, with the worker force generated as an extension of the queen (or cooperating queens) in each generation. Selection acts on the traits of the queen and the extrasomatic projection of her personal genome. This perception opens a new form of theoretical inquiry, which we illustrate in Box 1.

Box 1. A mathematical model for the evolution of eusociality.

Consider a solitary insect species that reproduces via progressive provisioning. Mated females build a nest, lay eggs and feed the larvae. When the larvae hatch the offspring leave the nest. We assume that the dispersal behavior can be affected by genetic mutations. We postulate a mutant allele, a, which induces daughters to stay with the nest. In our model there are three types of females: AA and Aa daughters leave the nest, while aa stay at the nest with probability, q, and become workers. Because of the haplodiploid genetics, there are only two types of males, A and a, both of whom leave the nest. There are six types of mated females: AA-A, AA-a, Aa-A, Aa-a, aa-A and aa-a. The first two letters denote the genotype of the female, and the third letter denotes the genotype of the sperm she has received. Only Aa-a and aa-a mothers establish colonies, because half of the daughters of Aa-a and all daughters of aa-a have genotype aa.

What are the conditions for the eusocial allele, a, to be favored over the solitary allele, A? As outlined in Part C of the supplementary online material the fundamental consideration is the following. In the presence of workers, the eusocial queen is expected to have two fitness advantages over solitary mothers: she has increased fecundity and reduced mortality. While her workers forage and feed the larvae, she can stay at home, which reduces her risk of predation, increases her oviposition rate and enables her (together with some workers) to defend the nest. Nevertheless, we find that the eusocial allele can invade the solitary one, only if these fitness advantages are large and arise already for small colony size. Moreover the probability, q, that aa daughters stay with the nest must be within a certain (sometimes narrow) parameter range. On the other hand, once the eusocial allele is dominant, it is easier for it to resist invasion by the solitary one. Therefore, the model explains why it is hard to evolve eusociality, but easier to maintain it once it has been established.

In our model relatedness does not drive the evolution of eusociality. But once eusociality has evolved, colonies consist of related individuals, because daughters stay with their mother to raise further offspring.

The interaction between queen and workers is not a standard cooperative dilemma, because the latter are not independent agents. Their properties depend on the genotype of the queen and the sperm she has stored. Moreover, daughters who leave the nest are not simply “defectors”; they are needed for the reproduction of the colony.

Inclusive fitness theory always claims to be a “gene-centered” approach, but instead it is “worker-centered”: it puts the worker into the center of attention and asks why does the worker behave altruistically and raise the offspring of another individual? The claim is that the answer to this question requires a theory that goes beyond the standard fitness concept of natural selection. But here we show that this is not the case. By formulating a mathematical model of population genetics and family structure, we see that there is no need for inclusive fitness theory. The competition between the eusocial and the solitary allele is described by a standard selection equation. There is no paradoxical altruism, no payoff matrix, no evolutionary game. A “gene-centered” approach for the evolution of eusociality makes inclusive fitness theory unnecessary.

The fourth phase is the proper subject of combined investigations in population genetics and behavioral ecology. Research programs have scarcely begun in this subject in part due to the relative neglect of the study of the environmental selection forces that shape early eusocial evolution. The natural history of the more primitive, and especially the structure of their nests and fierce defense of them, suggest that a key element in the origin of eusociality is defense against enemies, including parasites, predators, and rival colonies. But very few field and laboratory studies have been devised to test this and potential competing hypotheses.

In the fifth and final phase, between colony selection shapes the life cycle and caste systems of the more advanced eusocial species. As a result, many of the clades have evolved very specialized and elaborate social systems.

To summarize very briefly, we suggest that the full theory of eusocial evolution consists of a series of stages, of which the following may be recognized:

The formation of groups.

The occurrence of a minimum and necessary combination of preadaptive traits, causing the groups to be tightly formed. In animals at least, the combination includes a valuable and defensible nest.

The appearance of mutations that prescribe the persistence of the group, most likely by the silencing of dispersal behavior. Evidently, a durable nest remains a key element in maintaining the prevalence. Primitive eusociality may emerge immediately due to springloaded preadaptations.

Emergent traits caused by the interaction of group members are shaped through natural selection by environmental forces.

Multilevel selection drives changes in the colony life cycle and social structures, often to elaborate extremes.

We have not addressed the evolution of human social behavior here, but parallels with the scenarios of animal eusocial evolution exist, and they are, we believe, well worth examining.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Kathleen M. Horton for advice and help in preparing the manuscript. MAN and CET gratefully acknowledge support from the John Templeton Foundation, the NSF/NIH joint program in mathematical biology (NIH grant R01GM078986), the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (Grand Challenges grant 37874), and J. Epstein.

References

- 1.Hölldobler B, Wilson EO. The Ants. Harvard Univ. Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Foster KR, Ratnieks FLW. A new eusocial vertebrate? Trends Ecol Evol. 2005;20:363–364. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2005.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hamilton WD. The genetical evolution of social behaviour, I, II. J Theor Biol. 1964;7:1–52. doi: 10.1016/0022-5193(64)90038-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilson EO. The Insect Societies. Harvard Univ. Press; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wilson EO. Sociobiology: The New Synthesis. Harvard Univ. Press; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilson EO. One giant leap: How insects achieved altruism and colonial life. BioScience. 2008;50:17–25. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Linksvayer TA, Wade MJ. The evolutionary origin and elaboration of sociality in the aculeate Hymenoptera: maternal effects, sib-social effects, and heterochrony. Q Rev Biol. 2005;80:317–336. doi: 10.1086/432266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Queller DC, Strassmann JE. Kin selection and social insects. Bioscience. 1998;48:165–175. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Costa JT. The Other Insect Societies. Harvard Univ. Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cole BJ, Wiernacz DC. The selective advantage of low relatedness. Science. 1999;285:891–893. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5429.891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hughes WOH, Boomsma JJ. Genetic diversity and disease resistance in leaf-cutting ant societies. Evolution. 2004;58:1251–1260. doi: 10.1554/03-546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rheindt FE, Strehl CP, Gadau J. A genetic component in the determination of worker polymorphism in the Florida harvester ant Pogonomyrmex badius. Insectes Sociaux. 2005;52:163–168. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jones JJ, Myerscough MR, Graham S, Oldroyd BP. Honey bee nest thermoregulation: Diversity supports stability. Science. 2004;305:402–404. doi: 10.1126/science.1096340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schwander T, Rosset H, Chapuisat M. Division of labour and worker size polymorphism in ant colonies: The impact of social and genetic factors. Behav Ecol & Sociobiol. 2005;59:215–221. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wilson EO, Hölldobler B. Eusociality: Origin and consequence. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:13367–13371. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505858102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fletcher JA, Zwick M, Doebeli M, Wilson DS. What's wrong with inclusive fitness? Trends Ecol Evol. 2006;21:597–598. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2006.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Traulsen A. Mathematics of kin- and group-selection: Formally equivalent? Evolution. 2010;64:316–323. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2009.00899.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Doebeli M, Hauert C. Limits to Hamilton's rule. J Evol Biol. 2006;19:1386–1388. doi: 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2006.01157.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wolf JB, Wade MJ. On the assignment of fitness to parents and offspring: whose fitness is it and when does it matter? J Evol Biol. 2001;14:347–356. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grafen A. In: Behavioural Ecology. Krebs JR, Davies NB, editors. III. Blackwell Scientific Publications; 1984. pp. 62–84. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Frank SA. Foundations of Social Evolution. Princeton Univ. Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rousset F. Genetic Structure and Selection in Subdivided Populations. Princeton Univ. Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 23.van Veelen M. Group selection, kin selection, altruism and cooperation: When inclusive fitness is right and when it can be wrong. J Theor Biol. 2009;259:589–600. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2009.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fletcher JA, Doebeli M. A simple and general explanation for the evolution of altruism. Proc R Soc Lond B. 2009;276:13–19. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2008.0829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.West SA, Griffin AS, Gardner A. Evolutionary explanations for cooperation. Curr Biol. 2007;17:R661–R672. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nowak MA. Five rules for the evolution of cooperation. Science. 2006;314:1560–1563. doi: 10.1126/science.1133755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ohtsuki H, Hauert C, Lieberman E, Nowak MA. A simple rule for the evolution of cooperation on graphs and social networks. Nature. 2006;441:502–505. doi: 10.1038/nature04605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Traulsen A, Nowak MA. Evolution of cooperation by multilevel selection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:10952–10955. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602530103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Taylor PD, Day T, Wild G. Evolution of cooperation in a finite homogeneous graph. Nature. 2007;447:469–472. doi: 10.1038/nature05784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Antal T, Ohtsuki H, Wakeley J, Taylor PD, Nowak MA. Evolution of cooperation by phenotypic similarity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:8597–8600. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902528106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tarnita CE, Antal T, Ohtsuki H, Nowak MA. Evolutionary dynamics in set structured populations. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:8601–8604. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903019106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tarnita CE, Ohtsuki H, Antal T, Fu F, Nowak MA. Strategy selection in structured populations. J Theor Biol. 2009;259:570–581. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2009.03.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ohtsuki H, Nowak MA. Evolutionary games on cycles. Proc R Soc B. 2006;273:2249–2256. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2006.3576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grafen A. An inclusive fitness analysis of altruism on a cyclical network. J Evol Biol. 2007;20:2278–2283. doi: 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2007.01413.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hunt JH. The Evolution of Social Wasps. Oxford Univ. Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gadagkar R. The Social Biology of Ropalidia marginata: Toward Understanding the Evolution of Eusociality. Harvard Univ. Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thorne BL, Breisch NL, Muscedere ML. Evolution of eusociality and the soldier caste in termites: Influence of accelerated inheritance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:12808–12813. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2133530100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Khila A, Abouheif E. Evaluating the role of reproductive constraints in ant social evolution. Phil Trans R Soc B. 2010;365:617–630. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2009.0257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pepper JW, Smuts B. A mechanism for the evolution of altruism among nonkin: Positive assortment through environmental feedback. American Naturalist. 2002;160:205–213. doi: 10.1086/341018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fletcher JA, Zwick M. Strong altruism can evolve in randomly formed groups. J Theor Biol. 2004;228:303–313. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2004.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wade MJ. Group selections among laboratory populations of tribolium. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1976;73:4604–4607. doi: 10.1073/pnas.73.12.4604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Swenson W, Wilson DS, Elias R. Artificial ecosystem selection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:9110–9114. doi: 10.1073/pnas.150237597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wade MJ, Wilson DS, Goodnight C, Taylor D, Bar-Yam Y, de Aguiar MAM, Stacey B, Werfel J, Hoelzer GA, Brodie ED, Fields P, Breden F, Linksvayer TA, Fletcher JA, Richerson PJ, Bever JD, Van Dyken JD, Zee P. Multilevel and kin selection in a connected world. Nature. 2010;463:E8–E9. doi: 10.1038/nature08809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Clutton-Brock T. Cooperation between non-kin in animal societies. Nature. 2009;462:51–57. doi: 10.1038/nature08366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Johns PM, Howard KJ, Breisch NL, Rivera A, Thorne BL. Nonrelatives inherit colony resources in a primitive termite. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:17452–17456. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907961106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wilson DS, Wilson EO. Rethinking the theoretical foundation of sociobiology. Quart Rev Biol. 2007;82:327–348. doi: 10.1086/522809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wilson DS, Wilson EO. Evolution “for the good of the group. American Scientist. 2008;96:380–389. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sakagami SF, Maeta Y. In: Animals and Societies: Theories and Facts. Itô Y, Brown JL, Kikkawa J, editors. Japan Scientific Societies Press; 1987. pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wcislo WT. Social interactions and behavioral context in a largely solitary bee, Lasioglossum (Dialictus) figueresi (Hymenoptera, Halictidae) Insectes Sociaux. 1997;44:199–208. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jeanson R, Kukuk PF, Fewell JH. Emergence of division of labour in halictine bees: Contributions of social interactions and behavioural variance. Anim Behav. 2005;70:1183–1193. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Toth AL, Varala K, Newman TC, Miguez FE, Hutchison SK, Willoughby DA, Simons JF, Egholm M, Hunt JH, Hudson ME, Robinson GE. Wasp gene expression supports an evolutionary link between maternal behavior and eusociality. Science. 2007;318:441–444. doi: 10.1126/science.1146647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hunt JH, Kensinger BJ, Kossuth JA, Henshaw MT, Norberg K, Wolschin F, Amdam GV. A diapause pathway underlies the gyne phenotype in Polistes wasps, revealing an evolutionary route to caste-containing insect societies. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:14020–14025. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705660104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hunt JH, Amdam GV. Bivoltinism as an antecedent to eusociality in the paper wasp genus. Polistes Science. 2005;308:264–267. doi: 10.1126/science.1109724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Robinson GE, Page RE. In: The Genetics of Social Evolution. Breed MD, Page RE Jr, editors. Westview Press; 1989. pp. 61–80. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bonabeau E, Theraulaz G, Deneubourg JL. Quantitative study of the fixed threshold model for the regulation of division of labor in insect societies. Proc Roy Soc Lond B. 1996;263:1565–1569. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Abouheif E, Wray GA. Evolution of the gene network underlying wing polyphenism in ants. Science. 2002;297:249–252. doi: 10.1126/science.1071468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ross KG, Keller L. Genetic control of social organization in an ant. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:14232–14237. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.24.14232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.West-Eberhard MJ. Developmental Plasticity and Evolution. Oxford Univ. Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Duffy JE. In: Evolutionary Ecology of Social and Sexual Systems: Crustaceans as Model Organisms. Duffy JE, Thiel M, editors. Oxford Univ. Press; 2007. pp. 387–409. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sakagami SF, Hayashida K. Biology of the primitively social bee, Halictus duplex Dalla Torre, II: Nest structure and immature stages. Insectes Sociaux. 1960;7:57–98. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cowan DP. In: The Social Biology of Wasps. Ross KG, Mathews RW, editors. Comstock Pub. Associates; 1991. pp. 33–73. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.