Abstract

Tumor hypoxia is a negative prognostic factor and its precise imaging is of great relevance to therapy planning. The present review summarizes various strategies of probe design for imaging hypoxia with a variety of techniques such as PET, SPECT and fluorescence imaging. Synthesis of some important probes that are used for preclinical and clinical imaging and their mechanism of binding in hypoxia are also discussed.

Keywords: Hypoxia, Cancer, Molecular Imaging, Radiosynthesis, Fluorination, Fluorine-18, Copper-64, HIF-1, Carbonic Anhydrase IX, Positron Emission Tomography, Fluorescence, Single Photon Emission Computed Tomography

1. INTRODUCTION

In the 1950's two observations were made that have influenced the study of cancer biology and the clinical management of cancer in the half century since. Thomlinson and Gray noted the presence of regions of poor oxygenation with lung tumors, and associated these regions with ineffective vascular networks within the neoplasms [1]. Separately, Gray and others measured that tumor cells deprived of oxygen were resistant to radiation-induced killing by a factor of 2.5 – 3 relative to full oxygenated cells [2–4]. The incidence of poorly oxygenated or hypoxic cells within tumors and their prognostic significance has been a guiding principle for radiation and cancer biology in both the laboratory and the clinic in the following years. It has been noted that most tumors possess lower oxygen levels than their corresponding tissue of origin, as well as significant intra- and inter-tumoral variation in oxygen concentrations [5,6]. The resistance of hypoxic tumors to radiotherapy as well as a variety of types of chemotherapy has been repeatedly demonstrated [7,8]. In addition, hypoxic tumors have been shown to be associated with a more aggressive phenotype including increased potential for invasion, growth, and metastasis [9–16]. Hypoxia has therefore been well established as a key feature of the tumor microenvironment, one that significantly influences tumor behavior and can predict response to therapy.

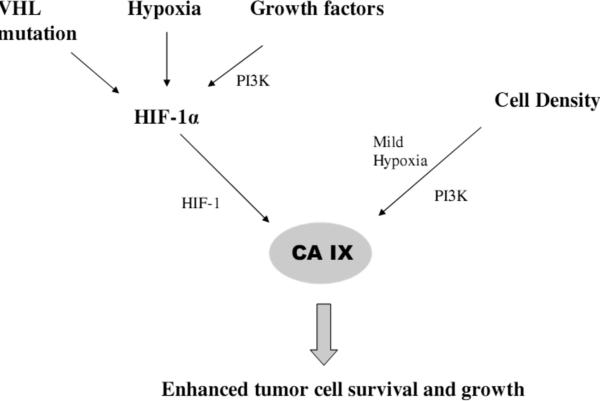

In addition to direct effects of oxygen on tumor response to therapy, hypoxia has been associated with several molecular signaling pathways that also influence tumor behavior. A key mediator of the ability of tumor cells to adapt to a low oxygen environment is the hypoxia-inducible factor 1 (HIF-1). HIF-1 is a composite protein consisting of an oxygen-regulated α subunit and a constitutively expressed β subunit. In the presence of oxygen, HIF-1α is hydroxylated and rapidly degraded by the proteasome [17]. The active transcription factor HIF-1 therefore only persists under hypoxic conditions, where it selectively activates transcription of genes bearing promoters containing HIF-1 binding hypoxia response elements (HREs). A number of clinical studies have shown that increased expression of HIF-1α is a significant negative prognostic indicator for many types of cancer, including brain [18,19], breast [20–22], cervix [23–25], esophagus [26], head and neck [27,28], and uterus [29]. Increased expression of HIF-1 and its downstream genes, including vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), glucose transporter 1 (GLUT-1), lysyl oxidase (LOX), and carbonic anhydrase IX (CA IX), appears to be at least partly responsible for the phenotype of increased aggressiveness, invasion, metastasis, and resistance to therapy associated with hypoxic tumor cells [30,31].

Given the strong association of hypoxia with tumor behavior and response to therapy, inclusion of this factor in cancer staging and treatment selection is of long-standing interest in oncology. In order to achieve such a hypoxia-guided clinical management strategy, a clinically-suitable method for identification and measurement of hypoxia within tumors must be realized. Previously invasive probe-based methods have been used, including the Eppendorf needle electrode [32] and optical needle probes such as the OxyLite [33]. Alternately, immunohistochemical methods have been applied to detect markers of hypoxia in biopsy samples taken from cancer patients. These markers include both exogenous, systemically-delivered probes that are administered to a patient, localize in hypoxic regions, and are detected by antibody techniques in tissue specimens, as well as endogenous proteins that are overexpressed under hypoxic conditions. However, the invasiveness of these procedures as well as their susceptibility to sampling error has encouraged the development of imaging-based methods for detecting and quantifying hypoxia within tumors.

While designing a hypoxia probe several factors must be considered. A good molecular probe for hypoxia should exhibit the following features:

-

1)

High accumulation in hypoxic tissues

-

2)

Rapid clearance of unbound tracer from normoxic tissues

-

3)

Low required dosage to eliminate any toxic effects

-

4)

Long retention time in hypoxic region

-

5)

Low metabolite formation

-

6)

Simple, rapid, high yield synthesis

-

7)

Low pharmacokinetic dependence on factors co-varying with hypoxia such as pH and blood flow

The pharmacokinetics and clinical data of most important hypoxia probes has been extensively reviewed [34–37]. It should be mentioned that even these guidelines are somewhat controversial; for example it has been argued that criterion #2, which generally implies a hydrophilic tracer with fast renal clearance, is unfeasible and that instead hypoxia probes should be hydrophobic with homogeneous distribution to all tissues, with probe accumulation in hypoxic areas increasing with time over background levels [38]. In this review we will discuss and evaluate a variety of molecular probes that have been developed for imaging hypoxia in tumors, with emphasis on the synthetic aspects. While imaging probes targeting hypoxia have been designed for a wide variety of imaging modalities, in this review we will focus on those in use in nuclear medicine and optical imaging applications.

2. STRATEGIES FOR IMAGING HYPOXIA

The most conceptually simple strategy for localizing an imaging probe within regions of low oxygenation is to induce accumulation through interaction between the molecule and oxygen and subsequent structural changes in the probe. This so-called “direct imaging” strategy is the most widely used method of detecting hypoxia technique and forms the basis of several imaging probes that are used clinically today.

However, as discussed above hypoxia triggers a cascade of signaling pathways in cells. The members of these pathways represent surrogates that can potentially be used as targets for imaging hypoxia. Such approaches are hereafter referred to as “indirect imaging” methods because they rely upon targets that are regulated by hypoxia, and not on oxygen directly. The extent to which these pathways correlate with hypoxia has been called into question, however many of these pathways have been strongly associated with clinical prognosis and they therefore remain significant targets for imaging tumor biology.

3. DIRECT IMAGING OF HYPOXIA WITH NITROIMIDAZOLES

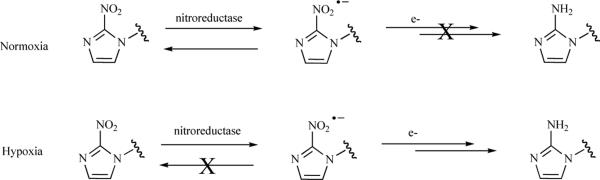

Molecules containing nitroimidazole groups have emerged as the most prevalent type of molecular hypoxia probe. The mechanism by which the nitroimidazole localizes within cells under hypoxic conditions has been thoroughly elucidated, and is summarized in Fig. (1). Cellular nitroreductase enzymes reduce the NO2 group to a nitro anion radical. This reversible process takes place in all cell types. In normoxia, adequate oxygen is present to oxidize the NO2 radical back to the original NO2 group. Thus the molecules shuttles between NO2 and NO2 anion as it circulates though tissues. The lack of oxygen in hypoxic cells prevents the radical anion from reverting back to the anion, and the radical is stabilized and further reduced to NHOH and subsequently NH2. The amine NH2 group is reactive and binds to cellular macromolecules, trapping it within the cell. Through this process the molecule accumulates in hypoxic tissues [35]. However the involvement of nitroreductase in the redox cycle of the nitroimidazole makes the NH2 formation and eventual intracellular trapping dependent on nitroreductase concentration in cells. This dependence on ancillary enzymes makes this strategy ”pseudo direct” as factors other than oxygen may influence probe accumulation.

Fig. (1).

Mechanism of intracellular retention of nitroimidazole-containing molecules.

While the nitroimidazole is the key molecular structure responsible for probe accumulation in hypoxia and is conserved among many hypoxia probes, the structure of the rest of the molecule attached to the nitroimidazole unit can be modified to alter the pharmacokinetics of the composite probe. Nitroimidazole-based probes are used for hypoxia detection through a number of techniques. Fig. (2) shows a selection of the major nitroimidazole-containing hypoxia markers for positron emission tomography (PET) [35], single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) [39] and immunohistochemistry [40–43].

Fig. (2).

Nitroimidazole-containing hypoxia probes.

3.1. Nitroimidazole-containing PET Probes

Positron emission tomography (PET) is a well-established molecular imaging modality that can report on the three-dimensional distribution of a positron-emitting probe with high spatial and quantitative accuracy. A hypoxia probe designed for detection with PET contains a positron emitting atom installed on a molecular structure that accumulates in hypoxia. PET imaging agents are commonly referred to as radiotracers because they can be administered and detected in trace doses. The positron emitter can be one of a number of isotopes including 13N, 11C, 18F, 64Cu, and 124I. Of these, radiotracers utilizing 18F and 64Cu will be discussed in this review. 18F and 64Cu have half lives of 109.8 and 762.1 minutes, which allow adequate time for the production of the tracer, transportation to the imaging facility, delivery to and circulation within a subject, and imaging.

3.1.1. [18F]-labeled Radiotracers

3.1.1.1. Nucleophilic Syntheses

Radiosynthesis of [18F]-labeled radiotracers targeting hypoxia commonly employ a nucleophilic route due to the reasonable availability of [18F]fluoride, relatively higher specific activity compared to an electrophilic route (discussed below), and ease of using radioactive fluoride compared to [18F]fluorine gas. The 18F-fluoride is generated by the nuclear reaction 18O(p,n)18F in a cyclotron (i.e. bombardment of H2 [18 O] by an accelerated proton beam). At the end of the bombardment a dilute solution of [18F]fluoride in H2 [18 O] is delivered from the cyclotron for immediate use in a radiosynthesis module. This solution is passed through a chromafix-18F cartridge that contains an ion exchange resin. The fluoride ions are retained by the resin while the H2 [18 O] and other water soluble impurities are passed through the cartridge and directed to waste. The resin-bound [18F]fluoride is eluted from the cartridge using a solution composed of acetonitrile, water, K2CO3 and Kryptofix 222 (K222). The eluent is evaporated to dryness by azeotropic removal of water with heat, vacuum, and a stream of helium gas. The dried [18F]fluoride complex, mostly in the form of potassium [18F]fluoride complexed with K222, remains in the reactor along with potassium carbonate. This anhydrous [18F]fluoride is used for the subsequent radiofluorination of the strategically designed precursor [44]. Crown ether can also be used in place of K222 to improve [18F]fluoride reactivity and sometimes eliminate K222's undesirable role of a competing nucleophile with [18F]fluoride [45–47]. In a similar fashion 18F-CsF can be produced using CsCO3 to offer some enhancement to fluoride solubility over potassium [18F]fluoride [48,49]. In the nucleophilic route a leaving group in the precursor is replaced by the fluoride ion. The presence of Kryptofix or crown ether renders the fluoride more soluble in the organic solvent of choice and improves its nucleophilicity. Some common leaving groups are often trimethyl ammonium salts, nitro groups, tosylates, mesylates, triflates, or halides. However, other more exotic reactions involving diazonium salts and click chemistry have also evolved to serve as useful tools for radiofluorination [50]. The precursor is conventionally heated with the dry fluoride in solvents like acetonitrile, dimethyl sulfoxide, dimethyl formamide for the reaction to take place. As in case of all radiochemical reactions, the precursor is in relatively larger excess over the [18F]fluoride; thus, the product must be separated from the precursor and other components (i.e., K222, inorganic [18F]fluoride) in the reaction which is typically achieved by using reverse phase HPLC and/or solid phase extraction.

3.1.1.2. Electrophilic Syntheses

In the electrophilic route the radioactive reagent is [18F]fluoride gas (18F2). Despite the notation “18F2”, the gas is in the form of 18F- 19F since labeling agent is made in the presence of carrier nonradioactive fluorine gas (19F2 ) which is in large excess. 18F2 with carrier fluorine gas is produced by bombarding deuterons with a mixture of 0.3% 19F2 in neon (20 Ne(d,α)18F). The carrier 19F2 is necessary to react with the produced 18F and also carry the 18F2 from the cyclotron to the radiosynthesis module. Since 18F2 can be only produced in “carrier added” form, electrophilic syntheses commonly result in lower product specific activity when compared to nucleophilc radiofluorination methods. The production of 18F2 requires significantly longer bombardment time as compared to that for the same activity of fluoride. In addition, due to the specific cyclotron target and deuteron-beam requirements for making 18F2, this labeling agent cannot be produced at all cyclotron facilities. Other drawbacks to use of 18F2 include the toxicity and corrosiveness of the F2 gas which over time causes damage to the reaction modules and demands efficient trapping of the exhaust gas to prevent it from release into the atmosphere.

3.1.1.3. [18F]-Fluoromisonidazole ([18F]-FMISO)

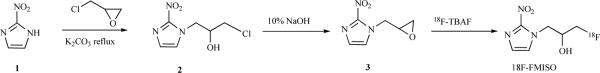

[18F]-fluoromisonidazole is hypoxia PET probe with the most history in preclinical and clinical use. The molecule is chiral and is used for injection as a racemic mixture. It has been shown that the biodistribution remains unaffected regardless of the enantiomeric purity. The original synthesis of FMISO was achieved as shown in Scheme 1. The nitroimidazole (1) opens the epoxide ring in epichlorohydrin to give the chlorohydrins 2. Reaction of 2 with aqueous NaOH produces the epoxide 3. The radiofluorination is carried out using 18F-tetrabutyl ammonium fluoride (18F-TBAF) as the labeling agent [51].

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of [18F]-FMISO.

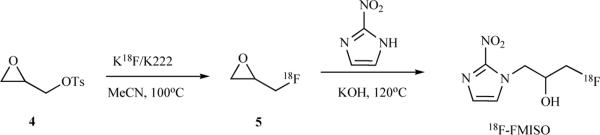

Another synthesis of FMISO has been reported that includes radiolabeling as a first step, followed by opening of the epoxide with the nitroimidazole (Scheme 2) The end of synthesis (EOS) radiochemical yield was 7–12 % [52].

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of [18F]-FMISO.

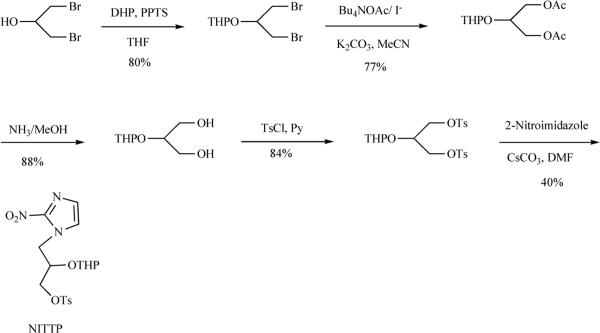

However, the dominant FMISO synthesis in use at present is that reported by Adamsen et al. [53], which has been automated using synthesis modules. The precursor NITTP can be prepared as shown in Scheme 3, and is also commercially available.

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of NITTP, a precursor for [18F]-FMISO.

NITTP is subjected to the labeling reaction in acetonitrile to give the THP protected product 6. The THP group is removed with aqueous HCl to produce [18F]-FMISO. The average radiochemical yield over these two steps has been reported to be 21% (n=5) at the end of synthesis (EOS) [52,53].

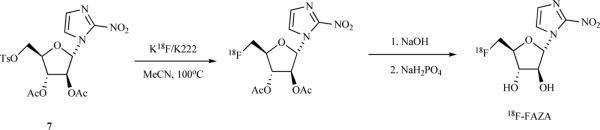

3.1.1.4. [18F]-Fluoroazomycin Arabinoside ([18F]-FAZA)

[18F]-FAZA is a second widespread PET radiotracer for imaging hypoxia that has been reported to offer improved contrast and reduced background signals relative to [18F]-FMISO. The automated synthesis of 18F-FAZA that is widely used is shown in Scheme 5. The precursor 7 is available commercially. After the radiolabeling step, the acetyl protecting groups are removed by basic hydrolysis followed by neutralization with NaH2PO4. The overall radiochemical yield is 20.7% (EOS).

Scheme 5.

Synthesis of 18F-FAZA.

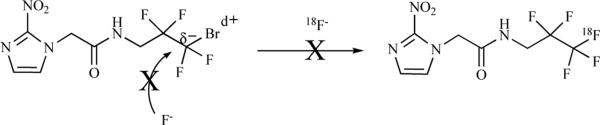

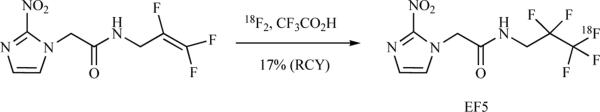

3.1.1.5. 2-(2-Nitro-1H-imidazol-1-yl)-N-(2,2,3,3,3-[18F]pentafluoropropyl)-acetamide ([18F]-EF5)

EF5 was originally developed as an immunohistochemical probe for hypoxia, however because of the fluorines within the compound it was subsequently developed as an [18F]-containing PET radiotracer. Attempts to radiolabel EF5 through a nucleophilic route have so far been unsuccessful [54]. Unlike other bromoalkanes, the bromine atom on polyfluoro alkane is partially positive and therefore cannot be displaced by a fluoride ion (Scheme 6).

Scheme 6.

Attempt of synthesis of 18F-EF5 using 18F−.

Since a preferred nucleophilic routed has not been achieved, radiosynthesis of [18F]-EF5 has been successfully made through an electrophilic reaction (Scheme 7) The tetrafluoro alkene precursor is dissolved in trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) and 18F2 is bubbled though it. The TFA is neutralized with NaOH, followed by extraction in a mixture of THF and chloroform. At this stage, radiochemical yield have been measured at 17% (EOS). The organic mixture is then further subjected to HPLC purification. Trifluoroacetic acid has been found to be the most effective solvent. An automated radiosynthesis of [18F]-EF5 has been recently reported with RCYs (6.1 ± 1.4%; n = 4) [55].

Scheme 7.

Synthesis of [18F]-EF5 using 18F2.

3.1.2. [64Cu]-containing Radiotracers

3.1.2.1. [64Cu(II)]-diacetyl-bis(N4-methylthiosemicarbazone) ([64Cu]-ATSM)

[64Cu]-ATSM is a non-nitroimidazole copper complex. The mechanism of hypoxia selectivity and retention of this molecule has been proposed in number of reports. A widely accepted mechanism is outlined in figure 3. 64Cu(II)-ATSM is reduced in both normoxic and hypoxic cells to unstable 64Cu(I)-ATSM. In normoxic cells this unstable species is oxidized back to 64Cu(II)-ATSM, whereas in hypoxic environment the unstable 64Cu(I) complex dissociates into 64Cu(I) ion and the ATSM ligand. The ionic 64copper moiety is trapped intracellularly. The hypoxia selectivity of ATSM-like copper(II) bis(thiosemicarbazones) complexes depend strongly upon the degree of alkylation of the ligand. A variety of alkyl substituents have been evaluated and Cu-ATSM has emerged as the most promising hypoxia imaging agent. Fig. (3) shows the positions and types of substituents used to vary the redox potential and hypoxia selectivity[56].

Fig. (3).

Cu-ATSM, its derivatives and proposed mechanism of action.

[64Cu]-ATSM is prepared by reacting [64Cu(II)]-acetate with the ATSM ligand in aqueous buffered DMSO solution. The reaction mixture is then passed over SepPak C 18 cartridge, and the cartridge is washed with water to remove unreacted copper(II) and DMSO. The cartridge is then eluted with ethanol to release the complex, and is formulated for use [57,58].

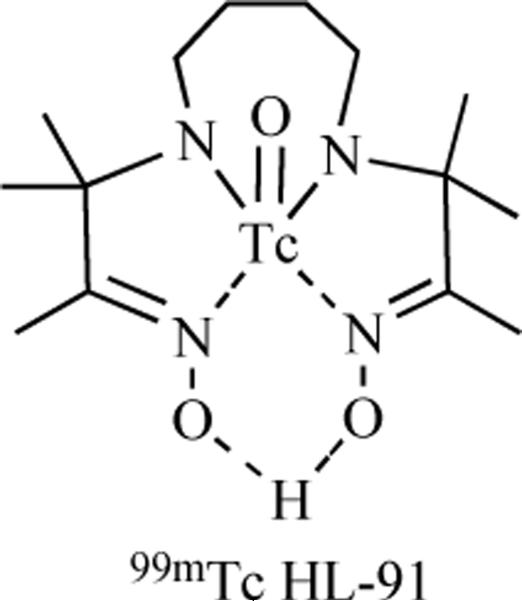

3.2. SPECT Probes for Hypoxia

Hypoxia-selective radiotracers incorporating nitroimidazoles have also been labeled with radioactive isotopes suitable for detection by single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT). [123I]-Iodoazomycin arabinoside has been prepared through an exchange reaction between the cold IAZA and Na[123I], and provides imaging performance similar to [18F]-FAZA. A distinct class of SPECT hypoxia-selective radiotracers are those incorporating 99mTc. Technetium-based SPECT agents are prepared by a general procedure as follows: radioactive 99mTc is obtained from 99mTc generator as a sodium pertechnate (NaTcO4) solution in saline. This solution is added to a solution of ligand and a reducing agent such as Sn2+ or Fe2+ in saline. The reducing agent reduces the 99mTc from its +7 oxidation state to a lower oxidation state which is then complexed with the ligand [59]. [99mTc]-HL91, also known as [99mTc]-BnAO, is a 99mTc SPECT hypoxia radiotracer that lacks a nitroimidazole unit [60,61]. Although the selectivity of this probe for hypoxia has been established, the mechanism of its accumulation in these regions has not been reported.

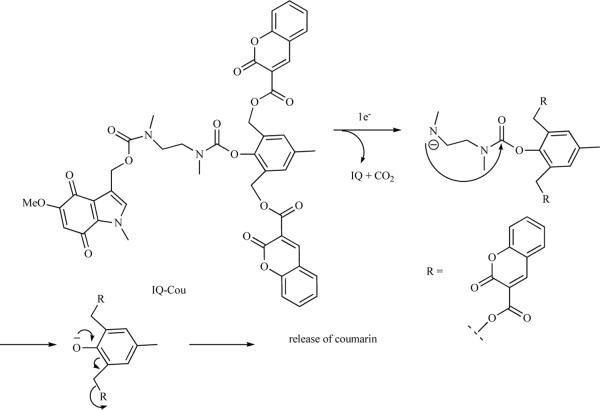

3.3. Fluorescent Probes for Hypoxia

The advantages of fluorescent probes relative to radioactive probes are reduced cost, capacity for indefinite storage, and the lack of ionizing radiation exposure for the chemist as well as the imaging subject. However, the ability of visible light to penetrate tissue limits their application to specific preclinical and clinical situations. A fluorescent probe consists of a chromophore attached to a compound of biologic interest. A fluorescent probe may be constitutive or activatable. A constitutive fluorescent probe is akin to a radioactive probe in that the release of fluorescent signal may occur at any time after production of the molecule. However, activatable fluorescent probes may be constructed in which the molecule becomes fluorescent only after a specific biochemical interaction. Activatable fluorescent hypoxia probes employ a fluorescent quenching group to suppress fluorescence under normoxic conditions. In a reductive environment the quencher unit is transformed into a nonquenching unit, or alternately is detached from the chromophore. The first reported probes employed a nitroimidazole unit that is known to quench the fluorescence [62]. In hypoxia the nitroimida zole is reduced to an aminoimidazole as described above, which does not quench the fluorescence of the rest of the molecule. In a recent report an indolequinone (IQ) has been used as the electron acceptor group linked to a coumarin-3-carboxylic acid (COU) as the chromophore. The molecule is non-fluorescent because IQ quenches the fluorescence of COU. Upon single electron reduction IQ undergoes a series of pi-bond shifts releasing Two COU units that show intense fluorescence at 420nM (Scheme 8) [63].

Scheme 8.

Mechanism of a coumarin based fluorescent hypoxia agent.

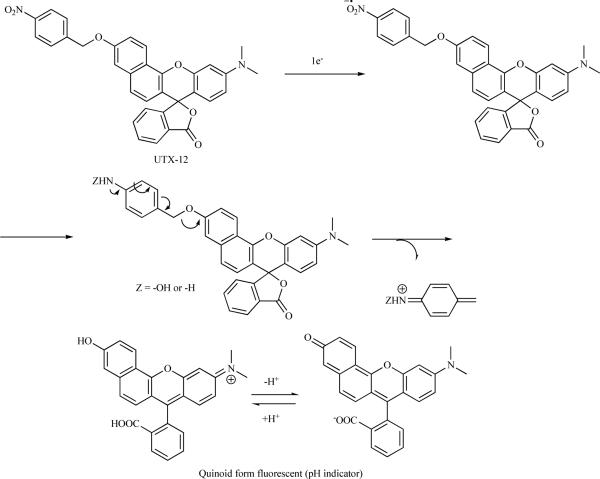

Nakata et al. reported the synthesis of a fluorescent probe that is sensitive to pH under hypoxia (Scheme 9). The probe is activated in hypoxia and shows a reversible dependence on pH. Another advantage of this probe is it shows fluorescence at longer wavelength than the previously reported probes, which is a desirable feature for in vivo studies as longer wavelengths of visible and infrared light propagate further through tissues [64].

Scheme 9.

A pH sensitive hypoxia probe.

4. INDIRECT IMAGING OF HYPOXIA

As discussed above, hypoxia triggers a cascade of signaling pathways in cells. These factors represent surrogates that can potentially be used as targets for imaging hypoxia. Hypoxia inducible factor (HIF1), xbox-binding protein 1 (XBP1) and carbonic anhydrase IX (CA IX) are such factors known to be overexpressed in hypoxia. While intracellular transcription factors such as HIF-1 and XBP1 are difficult to target with an imaging probe, CA IX, a target gene of HIF-1, has been further investigated as an imaging target. CA IX is a transmembrane protein with the catalytic binding site situated in the extracellular space. Overexpression of this enzyme in tumors may contribute to the reduced pH of the tumor extracellular space, which in turn expedites tumor growth and invasion by activating extracellular matrix metalloproteinases. Expression of CA IX is commonly used as a histologic marker of tissue hypoxia, although the extent to which this relationship holds has been called into question [65]. Figure 4 shows the relation between hypoxia, HIF-1 and CA IX. Although there are other factors responsible for expression of HIF-1 and CA IX, the contribution due to hypoxia remains significant.

Fig. (4).

[99mTc]-HL91, a non-nitroimidazole hypoxia SPECT radiotracer.

Carbonic anhydrase IX offers several features that make it a prime choice for targeting by molecular imaging techniques. CA IX is tightly regulated by HIF-1 and its significance in cancer has been established. The active site of CA IX is located on the extracellular domain of the protein, allowing targeting of the protein by probes that are not required to cross the cell membrane. Probe-based imaging methods for CA IX have therefore been developed employing several distinct strategies.

4.1. CA IX Imaging Probes

4.1.1. Antibodies

A number of antibodies to CA IX have been produced, including G250 and M75 [66,67]. A humanized chimeric form of G250 (cG250) has been radiolabeled and evaluated as an agent for imaging as well as radioimmunotherapy for CA IX-overexpressing renal cell cancers [68]. Studies of radiolabeled cG250 in rats bearing renal cell xenograft tumors have demonstrated that this agent achieves tumor to blood ratios of ~3 three days post-injection [69]. Preliminary clinical trials of [131I]-cG250 radioimmunotherapy have been conducted and exhibited a positive therapeutic effect in the treatment of renal cancers [70–72]. Radioimmunoscintigraphic imaging of this compound has demonstrated that at 2–3 days after injection cG250 selectively localizes in CA IX-expressing renal tumors while sparing other organs. This agent has recently been commercialized and is currently undergoing more widespread evaluation in the diagnosis and treatment of renal cancers. Engineered fragments of cG250 have also recently been developed and investigated as methods for targeting imaging and therapeutic agents, with similar pharmacokinetic profiles [73]. Chrastina and colleagues have studied M75 antibodies labeled with iodine-125 as a potential diagnostic and therapeutic agent [74]. The binding affinity of this antibody, which recognizes an epitope in the extracellular proteoglycan domain of CA IX, was measured to be 1.5 nM, with approximately 2.4 × 105 molecules of [125I]-M75 binding to a single hypoxic HT-29 colon adenocarcinoma cell in vitro. While antibodies facilitate the targeting of CA IX in tumors with high specificity, this method of localizing drugs and/or imaging probes requires circulation times on the order of 2 to 4 days in order to achieve optimal target-to-background ratios. This limits the type of labels that may be conjugated to the antibodies to generate CA IX imaging probes to long-lived radioactive isotopes ([64Cu], [124I]) or non-decaying signal-generating groups such as fluorophores.

4.1.2. Small Molecules

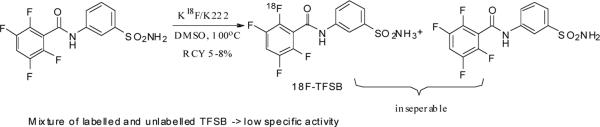

4.1.2.1. Radioactive Probes

Small molecule inhibitors of CA IX have also been investigated as vehicles for the development of CA IX-targeted imaging probes because of their more rapid pharmacokinetic uptake and clearance profiles relative to antibodies. A large number of CA IX inhibitors have been reported in the previous decade. [75–77] [78–80] Among these molecules containing a sulfonamide moiety have been found to be the most active. The compound 2,3,5,6-Tetrafluoro-3'-Sulfamoylbenzanilide (TFSB) is one of the most potent CA IX inhibitors reported to date, with an inhibitory coefficient of 0.8 nM[80]. Our group has labeled this molecule with [18F] to image CA IX in vivo. The labeling is done through a 19F-18F exchange reaction in DMSO at 140°C. Because the reactant and product are chemically identical the labeled product cannot be separated from unlabelled precursor, and as a result the reaction provides the tracer in a low specific activity (~250MBq/mmol). The probe exhibits high uptake in hypoxic cells in vitro compared to normoxic cells. In vivo microPET images obtained from mouse models of cancer are comparable in contrast to those obtained using [18F]-FAZA [81].

In order to improve the performance of a small molecule CA IX imaging agent it is necessary to design a probe that is comparably potent as TFSB but contains only one fluorine atom.

4.1.2.1. Fluorescent Probes

Recently Dubois et al. reported a fluorescent probe that has a fluorescent unit attached to sulfonamide. The molecule binds CA IX and accumulates in hypoxia in human HT-29 xenografts on mice. The accumulation was found to be reversible upon reoxygenation of the tumor (Fig. 6) [82].

Fig. (6).

A fluorescent CA IX probe.

5. CONCLUSIONS

A broad spectrum of imaging probes for the detection and localization of hypoxia have been synthesized and evaluated in both preclinical and clinical settings. These include probes that can be imaged through PET, SPECT, and fluorescence imaging. The mechanisms of localization of these probes range from those that interact directly with oxygen such as the nitroimidazoles, to those that target downstream products of hypoxia-activatable cellular pathways. While this arsenal of hypoxia probes has progressed to a degree where a large number are available for both laboratory and clinical investigations, evaluation of these probes, including a rigorous understanding of the biology they are designed to report on as well as demonstration of their clinical utility, is an ongoing effort.

Fig. (5).

Relation between hypoxia and CA IX.

Scheme 4.

Synthesis of [18F]-FMISO from NITTP.

Scheme 10.

Radiolabelling of [18F]-TFSB.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by NIH 1 R01 CA131199, NIH 1 P50 CA114747, and by a sponsored research agreement with Varian Biosynergy.

REFERENCES

- [1].Thomlinson RH, Gray LH. The histological structure of some human lung cancers and the possible implications for radiotherapy. Br. J. Cancer. 1955;9:539–549. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1955.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Read J. Mode of action of x-ray doses given with different oxygen concentrations. Br. J. Radiol. 1952;25:651–661. doi: 10.1259/0007-1285-25-294-336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Gray LH, Conger AD, Ebert M, Hornsey S, Scott OCA. The concentration of oxygen dissolved in tissues at the time of irradiation as a factor in radiotherapy. Br. J. Radiol. 1953;26:638–648. doi: 10.1259/0007-1285-26-312-638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Wright EA, Howard-Flanders P. The influence of oxygen on the radiosensitivity of mammalian tissues. Acta Radiol. 1957;48:26–32. doi: 10.3109/00016925709170930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Höckel M, Vaupel P. Tumor Hypoxia, Definitions and Current Clinical, Biologic, and Molecular Aspects. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2001;93:266–276. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.4.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Brown JM, Wilson WR. Exploiting tumor hypoxia in cancer treatment. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2004;4:437–447. doi: 10.1038/nrc1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Teicher BA, Lazo JS, Sartorelli AC. Classification of antineoplastic agents by their selective toxicities toward oxygenated and hypoxic tumor cells. Cancer Res. 1981;41:73–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Teicher BA, Holden SA, al-Achi A, Herman TS. Classification of antineoplastic treatments by their differential toxicity toward putative oxygenated and hypoxic tumor subpopulations in vivo in the FSaII murine fibrosarcoma. Cancer Res. 1990;50:3339–3344. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Young SD, Marshall RS, Hill RP. Hypoxia induces DNA overreplication and enhances metastatic potential of murine tumor cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1988;85:9533–9537. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.24.9533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Brizel DM, Scully SP, Harrelson JM, Layfield LJ, Bean JM, Prosnitz LR, Dewhirst MW. Tumor oxygenation predicts for the likelihood of distant metastases in human soft tissue sarcoma. Cancer Res. 1996;56:941–943. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Höckel M, Schlenger K, Aral B, Mitze M, Schaffer U, Vaupel P. Association between tumor hypoxia and malignant progression in advanced cancer of the uterine cervix. Cancer Res. 1996;56:4509–4915. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Brizel DM, Sibley GS, Prosnitz LR, Scher RL, Dewhirst MW. Tumor hypoxia adversely affects the prognosis of carcinoma of the head and neck. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 1997;38:285–289. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(97)00101-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Cuvier C, Jang A, Hill RP. Exposure to hypoxia, glucose starvation and acidosis: effect on invasive capacity of murine tumor cells and correlation with cathepsin (L + B) secretion. Clin. Exp. Metastasis. 1997;15:19–25. doi: 10.1023/a:1018428105463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Sundfor K, Lyng H, Rofstad EK. Tumour hypoxia and vascular density as predictors of metastasis in squamous cell carcinoma of the uterine cervix. Br. J. Cancer. 1998;78:822–827. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1998.586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Höckel M, Schlenger K, Höckel S, Vaupel P. Hypoxic cervical cancers with low apoptotic index are highly aggressive. Cancer Res. 1999;59:4525–4528. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Walenta S, Wetterling M, Lehrke M, Schwickert G, Sundfor K, Rofstad EK, Mueller-Klieser W. High lactate levels predict likelihood of metastases, tumor recurrence, and restricted patient survival in human cervical cancers. Cancer Res. 2000;60:916–921. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Chan DA, Sutphin PD, Yen SE, Giaccia AJ. Coordinate regulation of the oxygen-dependent degradation domains of hypoxia-inducible factor 1a. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2005;25:6415–6426. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.15.6415-6426.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Birner P, Gatterbauer B, Oberhuber G, Schindl M, Rossler K, Prodinger A, Budka H, Hainfellner JA. Expression of hypoxia-inducible factor-1a in oligodendrogliomas: its impact on prognosis and neoangiogenesis. Cancer. 2001;92:165–171. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010701)92:1<165::aid-cncr1305>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Korkolopoulou P, Patsouris E, Konstantinidou AE, Pavlopoulos PM, Kavantzas N, Boviatsis E, Thymara I, Perdiki M, Thomas-Tsagli E, Angelidakis D, Rologis D, Sakkas D. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1a/vascular endothelial growth factor axis in astrocytomas. Associations with microvessel morphometry, proliferation and prognosis. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 2004;30:267–278. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.2003.00535.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Schindl M, Schoppmann SF, Samonigg H, Hausmaninger H, Kwasny W, Gnant M, Jakesz R, Kubista E, Birner P, Oberhuber G. Overexpression of hypoxia-inducible factor 1a is associated with an unfavorable prognosis in lymph node-positive breast cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2002;8:1831–1837. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Bos R, van der Groep P, Greijer AE, Shvarts A, Meijer S, Pinedo HM, Semenza GL, van Diest PJ, van der Wall E. Levels of hypoxia-inducible factor-1a independently predict prognosis in patients with lymph node negative breast carcinoma. Cancer. 2003;97:1573–1581. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Dales JP, Garcia S, Meunier-Carpentier S, Andrac-Meyer L, Haddad O, Lavaut MN, Allasia C, Bonnier P, Charpin C. Overexpression of hypoxia-inducible factor HIF-1a predicts early relapse in breast cancer: Retrospective study in a series of 745 patients. Int. J. Cancer. 2005;116:734–739. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Birner P, Schindl M, Obermair A, Plank C, Breitnecker G, Oberhuber G. Overexpression of hypoxia-inducible factor 1a is a marker for an unfavorable prognosis in early-stage cervical cancer. Cancer Res. 2000;60:4693–4696. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Burri P, Djonov V, Aebersold DM, Lindel K, Studer U, Altermatt HJ, Mazzucchelli L, Greiner RH, Gruber G. Significant correlation of hypoxia-inducible factor-1a with treatment outcome in cervical cancer treated with radical radiotherapy. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2003;56:494–501. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(02)04579-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Ishikawa H, Sakurai H, Hasegawa M, Mitsuhashi N, Takahashi M, Masuda N, Nakajima M, Kitamoto Y, Saitoh J, Nakano T. Expression of hypoxia-inducible factor 1a predicts metastasis-free survival after radiation therapy alone in stage IIIB cervical squamous cell carcinoma. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2004;60:513–521. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2004.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Kimura S, Kitadai Y, Tanaka S, Kuwai T, Hihara J, Yoshida K, Toge T, Chayama K. Expression of hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1a is associated with vascular endothelial growth factor expression and tumor angiogenesis in human oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Eur. J. Cancer. 2004;40:1904–1912. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2004.04.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Aebersold DM, Burri P, Beer KT, Laissue J, Djonov V, Greiner RH, Semenza GL. Expression of hypoxia-inducible factor-1a: a novel predictive and prognostic parameter in the radiotherapy of oropharyngeal cancer. Cancer Res. 2001;61:2911–2916. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Koukourakis MI, Giatromanolaki A, Sivridis E, Simopoulos C, Turley H, Talks K, Gatter KC, Harris AL. Hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF1A and HIF2A), angiogenesis, and chemoradiotherapy outcome of squamous cell head-and-neck cancer. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2002;53:1192–1202. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(02)02848-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Sivridis E, Giatromanolaki A, Gatter KC, Harris AL, Koukourakis MI. Association of hypoxia-inducible factors 1a and 2a with activated angiogenic pathways and prognosis in patients with endometrial carcinoma. Cancer. 2002;95:1055–1063. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Semenza GL. Targeting HIF-1 for Cancer Therapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2003;3:721–732. doi: 10.1038/nrc1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Erler JT, Bennewith KL, Nicolau M, Dornhofer N, Kong C, Le QT, Chi JT, Jeffrey SS, Giaccia AJ. Lysyl oxidase is essential for hypoxia-induced metastasis. Nature. 2006;440:1222–1226. doi: 10.1038/nature04695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Kallinowski F, Zander R, Höckel M, Vaupel P. Tumor tissue oxygenation as evaluated by computerized pO2-histography. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 1990;19:953–961. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(90)90018-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Griffiths JR, Robinson SP. The OxyLite: a fibre-optic oxygen sensor. Br. J. Radiol. 1999;72:627–630. doi: 10.1259/bjr.72.859.10624317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Krohn KA, Link JM, Mason RP. Molecular imaging of hypoxia. J. Nucl. Med. 2008;49:129S–48S. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.107.045914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Nunn A, Linder K, Strauss HW. Nitroimidazoles and imaging hypoxia. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. 1995;22:265–280. doi: 10.1007/BF01081524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Martin GV, Cerqueira MD, Caldwell JH, Rasey JS, Embree L, Krohn KA. Fluoromisonidazole. A metabolic marker of myocyte hypoxia. Circ. Res. 1990;67:240–4. doi: 10.1161/01.res.67.1.240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Minn H, Gronroos TJ, Komar G, Eskola O, Lehtio K, Tuomela J, Seppanen M, Solin O. Imaging of tumor hypoxia to predict treatment sensitivity. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2008;14:2932–2942. doi: 10.2174/138161208786404380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Tatum JL, Kelloff GJ, Gillies RJ, Arbeit JM, Brown JM, Chao KS, Chapman JD, Eckelman WC, Fyles AW, Giaccia AJ, Hill RP, Koch CJ, Krishna MC, Krohn KA, Lewis JS, Mason RP, Melillo G, Padhani AR, Powis G, Rajendran JG, Reba R, Robinson SP, Semenza GL, Swartz HM, Vaupel P, Yang D, Croft B, Hoffman J, Liu G, Stone H, Sullivan D. Hypoxia: importance in tumor biology, noninvasive measurement by imaging, and value of its measurement in the management of cancer therapy. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 2006;82:699–757. doi: 10.1080/09553000601002324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Chapman JD, Engelhardt EL, Stobbe CC, Schneider RF, Hanks GE. Measuring hypoxia and predicting tumor radioresistance with nuclear medicine assays. Radiother. Oncol. 1998;46:229–237. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8140(97)00186-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Arteel GE, Thurman RG, Yates JM, Raleigh JA. Evidence that hypoxia markers detect oxygen gradients in liver: pimonidazole and retrograde perfusion of rat liver. Br. J. Cancer. 1995;72:889–895. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1995.429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Evans SM, Jenkins WT, Joiner B, Lord EM, Koch CJ. 2-Nitroimidazole (EF5) binding predicts radiation resistance in individual 9L s.c. tumors. Cancer Res. 1996;56:405–411. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Raleigh JA, Calkins-Adams DP, Rinker LH, Ballenger CA, Weissler MC, Fowler WC, Jr., Novotny DB, Varia MA. Hypoxia and vascular endothelial growth factor expression in human squamous cell carcinomas using pimonidazole as a hypoxia marker. Cancer Res. 1998;58:3765–3768. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Russell J, Carlin S, Burke SA, Wen B, Yang KM, Ling CC. Immunohistochemical detection of changes in tumor hypoxia. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2009;73:1177–1186. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Cai L, Lu S, Pike VW. Chemistry with [18F]fluoride ion. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2008:2853–2873. [Google Scholar]

- [45].Chin FT, Morse CL, Shetty HU, Pike VW. Automated radiosynthesis of [18F]SPA-RQ for imaging human brain NK1 receptors with PET. J. Labelled Compd. Rad. 2006;49:17–31. [Google Scholar]

- [46].Block D, Klatte B, Knochel A, Beckmann R, Holm U. No-carrier-added fluorine-18-labeling of aliphatic compounds in high yields via aminopolyether-supported nucleophilic substitution. J. Labelled Compd. Rad. 1986;23:467–477. [Google Scholar]

- [47].Briard E, Zoghbi SS, Simeon FG, Imaizumi M, Gourley JP, Shetty HU, Lu S, Fujita M, Innis RB, Pike VW. Single-Step High-Yield Radiosynthesis and Evaluation of a Sensitive 18F-Labeled Ligand for Imaging Brain Peripheral Benzodiazepine Receptors with PET. J. Med. Chem. 2009;52:688–699. doi: 10.1021/jm8011855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Becaud J, Mu L, Karramkam M, Schubiger PA, Ametamey SM, Graham K, Stellfeld T, Lehmann L, Borkowski S, Berndorff D, Dinkelborg L, Srinivasan A, Smits R, Koksch B. Direct one-step 18F-labeling of peptides via nucleophilic aromatic substitution. Bioconjug. Chem. 2009;20:2254–2261. doi: 10.1021/bc900240z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Lee SJ, Oh SJ, Chi DY, Kil HS, Kim EN, Ryu JS, Moon DH. Simple and highly efficient synthesis of 3'-deoxy-3'-[18F]fluorothymidine using nucleophilic fluorination catalyzed by protic solvent. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging. 2007;34:1406–1409. doi: 10.1007/s00259-007-0391-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Mamat C, Ramenda T, Wuest FR. Recent applications of click chemistry for the synthesis of radiotracers for molecular imaging. Mini Rev. Org. Chem. 2009;6:21–34. [Google Scholar]

- [51].Hwang DR, Dence CS, Bonasera TA, Welch MJ. No-carrier-added synthesis of 3-[18F]fluoro-1-(2-nitro-1-imidazolyl)-2-propanol. A potential PET agent for detecting hypoxic but viable tissues. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 1989;40:117–126. doi: 10.1016/0883-2889(89)90186-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Kaemaeraeinen E-L, Kylloenen T, Nihtilae O, Bjoerk H, Solin O. Preparation of fluorine-18-labeled fluoromisonidazole using two different synthesis methods. J. Labelled Compd. Rad. 2004;47:37–45. [Google Scholar]

- [53].Adamsen TCH, Grierson JR, Krohn KA. A new synthesis of the labeling precursor for [18F]-fluoromisonidazole. J. Labelled Compd. Rad. 2005;48:923–927. [Google Scholar]

- [54].Dolbier WR, Jr., Li AR, Koch CJ, Shiue CY, Kachur AV. [18F]-EF5, a marker for PET detection of hypoxia: synthesis of precursor and a new fluorination procedure. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 2001;54:73–80. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8043(00)00102-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Chin FT, Subbarayan M, Sorger J, Gambhir SS, Graves EE. Automated Radiosynthesis of [F-18]EF-5 for Imaging Hypoxia in Human. J. Labelled Compd. Rad. 2009;52:S274. [Google Scholar]

- [56].Vavere AL, Lewis JS. Cu-ATSM: A radiopharmaceutical for the PET imaging of hypoxia. Dalton Trans. 2007:4893–4902. doi: 10.1039/b705989b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Gingras BA, Suprunchuk T, Bayley CH. Preparation of some thiosemicarbazones and their copper complexes. III. Can. J. Chem. 1962;40:1053–1059. [Google Scholar]

- [58].Bonnitcha PD, Vavere AL, Lewis JS, Dilworth JR. In vitro and in vivo evaluation of bifunctional bisthiosemicarbazone 64Cu-complexes for the positron emission tomography imaging of hypoxia. J. Med. Chem. 2008;51:2985–2991. doi: 10.1021/jm800031x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Nosco DL, Beaty-Nosco JA. Chemistry of technetium radiopharmaceuticals 1: Chemistry behind the development of technetium-99m compounds to determine kidney function. Coordin. Chem. Rev. 1999;184:91–123. [Google Scholar]

- [60].Cook GJ, Houston S, Barrington SF, Fogelman I. Technetium-99m-labeled HL91 to identify tumor hypoxia: correlation with fluorine-18-FDG. J. Nucl. Med. 1998;39:99–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Zhang X, Melo T, Ballinger JR, Rauth AM. Studies of 99mTc-BnAO (HL-91): a non-nitroaromatic compound for hypoxic cell detection. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 1998;42:737–740. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(98)00301-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Hodgkiss RJ, Middleton RW, Parrick J, Rami HK, Wardman P, Wilson GD. Bioreductive fluorescent markers for hypoxic cells: a study of 2-nitroimidazoles with 1-substituents containing fluorescent, bridgehead-nitrogen, bicyclic systems. J. Med. Chem. 1992;35:1920–1926. doi: 10.1021/jm00088a030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Liu Y, Xu Y, Qian X, Liu J, Shen L, Li J, Zhang Y. Novel fluorescent markers for hypoxic cells of naphthalimides with two heterocyclic side chains for bioreductive binding. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2006;14:2935–2941. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2005.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Nakata E, Yukimachi Y, Kariyazono H, Im S, Abe C, Uto Y, Maezawa H, Hashimoto T, Okamoto Y, Hori H. Design of a bioreductively-activated fluorescent pH probe for tumor hypoxia imaging. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2009;17:6952–6958. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2009.08.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Sobhanifar S, Aquino-Parsons C, Stanbridge EJ, Olive P. Reduced expression of hypoxia-inducible factor-1a in perinecrotic regions of solid tumors. Cancer Res. 2005;65:7259–7266. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Oosterwijk E, Ruiter DJ, Hoedemaeker PJ, Pauwels EK, Jonas U, Zwartendijk J, Warnaar SO. Monoclonal antibody G 250 recognizes a determinant present in renal-cell carcinoma and absent from normal kidney. Int. J. Cancer. 1986;38:489–494. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910380406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Pastoreková S, Zavadova Z, Kostal M, Babusikova O, Zavada J. A novel quasi-viral agent, MaTu, is a two-component system. Virology. 1992;187:620–626. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(92)90464-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Velders MP, Litvinov SV, Warnaar SO, Gorter A, Fleuren GJ, Zurawski VR, Coney LR. New chimeric anti-pancarcinoma monoclonal antibody with superior cytotoxicity-mediating potency. Cancer Res. 1994;54:1753–1759. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Brouwers A, Verel I, Van Eerd J, Visser G, Steffens M, Oosterwijk E, Corstens F, Oyen W, Van Dongen G, Boerman O. PET Radioimmunoscintigraphy of Renal Cell Cancer Using 89Zr-Labeled cG250 Monoclonal Antibody in Nude Rats. Cancer Biother. Radiopharm. 2004;19:155–163. doi: 10.1089/108497804323071922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Divgi CR, O'Donoghue JA, Welt S, O'Neel J, Finn R, Motzer RJ, Jungbluth A, Hoffman E, Ritter G, Larson SM, Old LJ. Phase I Clinical Trial with Fractionated Radioimmunotherapy using 131I-labeled Chimeric G250 in Metastatic Renal Cancer. J. Nucl. Med. 2004;45:1412–1421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Brouwers AH, Dörr U, Lang O, Boerman OC, Oyen WJG, Steffens MG, Oosterwijk E, Mergenthaler HG, Bihl H, Corstens FHM. 131I-cG250 monoclonal antibody immunoscintigraphy versus [18F]FDG-PET imaging in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma: a comparative study. Nucl. Med. Commun. 2002;23:229–236. doi: 10.1097/00006231-200203000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Brouwers AH, Buijs WCAM, Mulders PFA, de Mulder PHM, van den Broek WJM, Mala C, Oosterwijk E, Boerman OC, Corstens FHM, Oyen WJG. Radioimmunotherapy with [131I]cG250 in Patients with Metastasized Renal Cell Cancer: Dosimetric Analysis and Immunologic Response. Clin. Cancer Res. 2005;11:7178s–7186s. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-1004-0010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Brouwers A, Mulders P, Oosterwijk E, Buijs W, Corstens F, Boerman O, Oyen W. Pharmacokinetics and Tumor Targeting of 131I-Labeled F(ab')2 Fragments of the Chimeric Monoclonal Antibody G250: Preclinical and Clinical Pilot Studies. Cancer Biother. Radiopharm. 2004;19:466–477. doi: 10.1089/cbr.2004.19.466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Chrastina A, Závada J, Parkkila S, Kaluz Š, Kaluzová M, Rajcáni J, Pastorek J, Pastoreková S. Biodistribution and Pharmacokinetics of 125I-labeled Monoclonal Antibody M75 Specific for Carbonic Anhydrase IX, an Intrinsic Marker of Hypoxia, in Nude Mice Xenografted with Human Colorectal Carcinoma. Int. J. Cancer. 2003;105:873–881. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Thiry A, Delayen A, Goossens L, Houssin R, Ledecq M, Frankart A, Dogne J-M, Wouters J, Supuran CT, Henichart J-P, Masereel B. Synthesis and biological evaluation of a new family of anti-benzylanilinosulfonamides as CA IX inhibitors. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2009;44:511–518. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2008.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Thiry A, Ledecq M, Cecchi A, Dogne JM, Wouters J, Supuran CT, Masereel B. Indanesulfonamides as carbonic anhydrase inhibitors. Toward structure-based design of selective inhibitors of the tumor-associated isozyme CA IX. J. Med. Chem. 2006;49:2743–2749. doi: 10.1021/jm0600287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Thiry A, Ledecq M, Cecchi A, Frederick R, Dogne J-M, Supuran CT, Wouters J, Masereel B. Ligand-based and structure-based virtual screening to identify carbonic anhydrase IX inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2009;17:553–557. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2008.11.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Abbate F, Casini A, Owa T, Scozzafava A, Supuran Claudiu T. Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors: E7070, a sulfonamide anticancer agent, potently inhibits cytosolic isozymes I and II, and transmembrane, tumor-associated isozyme IX. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2004;14:217–23. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2003.09.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Pastorekova S, Casini A, Scozzafava A, Vullo D, Pastorek J, Supuran Claudiu T. Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors: the first selective, membrane-impermeant inhibitors targeting the tumor-associated isozyme IX. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2004;14:869–73. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2003.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Vullo D, Scozzafava A, Pastorekova S, Pastorek J, Supuran CT. Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors: inhibition of the tumor-associated isozyme IX with fluorine-containing sulfonamides. The first subnanomolar CA IX inhibitor discovered. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2004;14:2351–2356. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2004.01.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Zhang L, Cecic I, Cheng Z, Gambhir SS, Graves EE. 4th Annual Meeting of the Society for Molecular Imaging; Cologne, Germany. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- [82].Dubois L, Lieuwes NG, Maresca A, Thiry A, Supuran CT, Scozzafava A, Wouters BG, Lambin P. Imaging of CA IX with fluorescent labelled sulfonamides distinguishes hypoxic and (re)-oxygenated cells in a xenograft tumour model. Radiother. Oncol. 2009;92:423–428. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2009.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]