Abstract

Background

Visceral leishmaniasis (kala-azar) is an endemic disease in some areas of Iran. A cross- sectional study was conducted for sero-epidemiological survey of visceral leishmaniasis (VL) in Baft district from Kerman Province, southeast of Iran.

Methods

Blood samples were collected from children up to 12 years old and 10% of adult population from Baft villages with a multi-stage randomized cluster sampling. In addition, blood samples were collected from 30 domestic dogs from the same areas. All the collected blood samples were tested by direct agglutination test (DAT) for the detection of anti-Leishmania antibodies in both human and dog using the cut-off value of ≥1:3200 and ≥1:320, respectively. Parasitological, molecular, and pathological were performed on infected dogs. Chi-square and Fisher exact tests were used to compare sero-prevalence values.

Results

From 1476 collected human serum samples, 23 (1.55%) showed anti-Leishmania antibodies at titers of 1:800 and 1:1600 whereas 14 (0.95%) showed anti-Leishmania infantum antibodies at titers of ≥1:3200. No statistically significant difference was found between male (1.18%) and female (0.69%) sero-prevalence (P=0.330). Children of 5-8 years showed the highest sero-prevalence rate (3.22%). Seven out of 30 domestic dogs (23%) showed anti-Leishmania antibodies at titers ≥1:320. Leishmania infantum was identified in five infected dogs by nested – PCR assay.

Conclusion

It seems that visceral leishmaniasis is being endemic in southern villages of Baft district, southeast of Iran.

Keywords: Visceral leishmaniasis, Sero-epidemiology, Direct agglutination test, Human, Iran

Introduction

Leishmaniasis caused by protozoan parasite of the Leishmania spp. transmitted by phlebotomine sand flies (1, 2). VL is the most severe form of leishmaniasis in the world, which is responsible for an estimated 500,000 cases each year worldwide (3). The parasite migrates to the reticulo-endotelial organs such as liver, spleen, and bone marrow and if left untreated it will always result in the death in the host (3). Signs and symptoms of VL include on fever, weight loss, mucosal ulcers, fatigue, anemia, and substantial hyperplasia of the liver and spleen (4).

Visceral leishmaniasis is greatly widespread in the Middle East region caused by L. infantum and domestic dogs (Canis familiaris) are principal reservoir hosts of the disease (4).

The first case of VL in Iran was reported from the northern part of Iran in 1949. Increasing numbers of VL cases have been diagnosed from other parts of Iran (5–13). At least six endemic foci of VL have been known in some areas of Ardabil, East Azerbaijan, Fars, Boushehr and recently from Qom and northern Khorasan Provinces (5–13). Recently, sporadic cases of leishm-aniasis are reported from other parts of Iran (13).

In recent decades, 108 cases of VL have been reported and passively registered in Kerman Province (14). All cases have been referred from health houses and health clinics to pediatrics wards of Afzalipour Medical Center at Kerman University of Medical Sciences. Approximately half of these cases were registered from Baft (14, 15).

In children under 12 years old from Baft district, about 20% of collected serum samples were positive at titers ≥1:20 with IFAT and two of the children were positive at titers 1:320 (16). Based on the study that was performed on 126 carnivores for the detection of Leishmania infection in Baft district in 1994, 65.9% of dogs, 25.4% of jackals and 8.7% of foxes were sero-positive and amastigote forms were found in one stray dog (17). The fauna and monthly activity of sand flies are also reported in Baft district and the predominant species of Phlebotomus were identified P. papatasi (33.74%) and P. alexandri (29.82%) (18).

Serological methods are highly sensitive and non-invasive, so they are appropriate for use in field conditions (19). In this study, the DAT was used as sero-diagnostic tool because it is simple and valid test and does not require specialized equipments (7, 13, 20, 21, 28). The confirmation diagnostic method of VL in suspected dogs is biopsy tissue preparation from spleen, bone marrow, liver, lymphatic glands and demonstration of amastigote form of Leishmania spp. or culture of the biopsy samples in enriched culture media for the growth of promastigote forms of the parasite (4).

The objective of this study was to determine the sero-prevalence of VL in the Baft district and to identify the animal reservoir hosts of the disease for implementation of control program.

Material and Methods

Study area

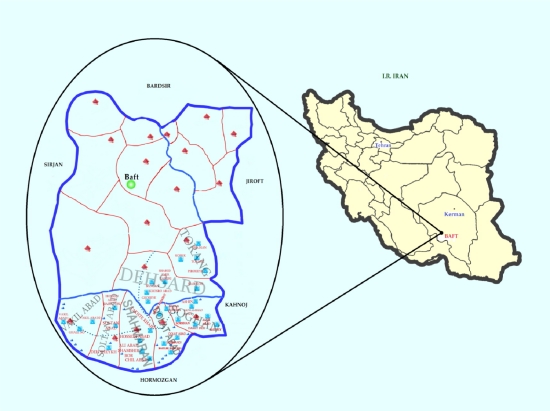

Baft district is located in the south-west of Kerman City, southeastern Iran (Fig. 1). The study area has moderate weather with an altitude of 2250 m above the sea level and approximately 13299.77 km2 with 4 urban centers, 634 villages and 145014 population. Almost 41.7 % of its population are living in urban areas, 56.8 % live in rural areas and 1.5 % of the else population have nomadic living (18). This investigation was carried out in the residents of 30 villages of Baft in a period of 12 months from April 2009 to March 2010.

Fig. 1.

Geographical locations where this study was carried out

Sampling

A cross-sectional study was conducted from April 2009 to March 2010 and a multi stage randomized cluster sampling method was used for the sample collection. Thirty villages (cluster) from 634 villages in Baft district where human VL was reported in 10 years ago were randomly selected. In each cluster, serum samples were taken from 50 children of ≤12 years old randomly.

Blood samples were collected from 1374 children under 12 years old (93%) and 102 adults (7%) in heparinized capillary tubes and processed them 4-10 h after collection. The collected blood samples were centrifuged at 10000 ×g for 5 min and the separated plasma samples were stored at −20°C. In addition, serum samples were prepared from two suspected patients who had been referred to the pediatric ward of the Afzalipour Medical Center (AMC), in Kerman Province.

In addition, samples were taken from 30 domestic dogs. All the selected dogs were physically examined by a doctor of veterinary medicine. Dogs' age was determined by interviewing dog owners. Blood samples were taken from the selected dogs with venapuncture in the same villages where human samples were taken, poured into 10 ml polypropylene tubes centrifuged at 800 ×g for 5-10 min within 4-10 h after their collection.

All the blood samples were tested by DAT in the parasitology laboratory at the School of Medicine, Kerman University of Medical Sciences.

The smears prepared from spleen and liver of suspected domestic dogs, stained by Giemsa and examined carefully by light microscope at high magnification (×1000) for the demonstration of amastigote forms of Leishmania spp. The culture samples in NNN were checked for promastigotes twice a week for 6 weeks. Necropsy was performed on all of the infected dogs for parasitological, molecular, and pathological examinations.

Serological tests

The L. infantum antigens were prepared in the protozoology unit of the School of Public Health, Tehran University of Medical Sciences.

The principal phases of the procedure for preparing DAT antigen were mass production of promastigotes of L. infantum Lon49 (Iranian strain) in RPMI1640 plus 10% fetal bovine serum, tripsinization of the parasites, fixing with formaldehyde 2% and staining with Coomassie brilliant blue (7, 13, 22, 23, 28).

The human and dog sera were tested by DAT, initially, for screening purposes; dilutions were made at 1:800 and 1:3200 for human's samples also 1:80 and 1:320 for dogs' samples. Samples with titers of 1:3200 in human and 1:320 in dogs were further diluted to end-point titer of 1:102400 in human's samples and 1:20480 in dog's samples. Negative control wells (antigen only on each plate) with confirmed negative and positive control sera were tested in each plate daily. The cut- off value was defined as the highest dilution which agglutination was visible, as blue dot, compared with negative control wells, which had clear blue dots. The positive standard control serum prepared from human and dogs with L. infantum infection in an endemic area and confirmed by parasitological methods.

Quantitative results obtained with DAT are expressed as an antibody titer, the reciprocal of the highest dilution at which agglutination (large diffuse blue mats) was visible after 12-18 h incubation at room temperature (13, 20, 22, 23).The cut-off was based on previous studies (7–10, 13, 22, 23, 28).The anti-Leishmania antibody titers at ≥ 1:320 and ≥ 1: 3200 were considered positive for dog and human Leishmania infection, respectively.

Parasitological study

For confirm Leishmania infection in dogs, all the sero-positive dogs (≥1:320) were dissected after euthanasia and impression smears prepared from spleen of each the animal. All the prepared smears were fixed with methanol, stained with Giemsa, and examined microscopically for the demonstration of amastigotes.

Pathological study

To confirm any pathological changes caused by visceral leishmaniasis, the samples were prepared from the spleen and liver of all sero-positive dogs (≥ 1:320) after their dissection, placed in vial containing formalin10% and transferred to the pathology laboratory. The samples were examined after blocking and preparing cuts of 3µm by microtome (Leitz 1512) and stained with hematoxylin-eosin for the presence of amastigote stages and any pathological changes.

Molecular characterization

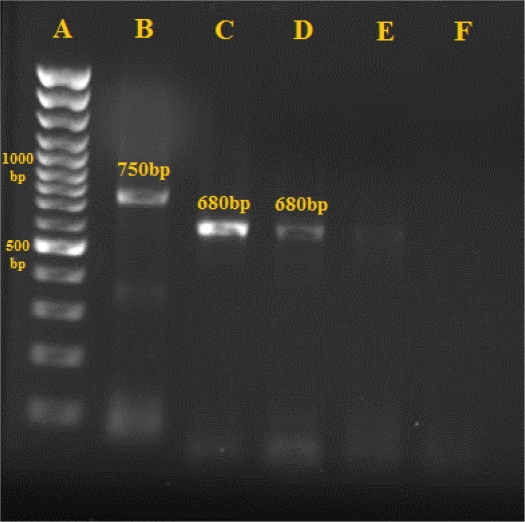

Biopsy specimens were collected aseptically from spleen of five sero-positives and autopsied dogs then cultured the samples in Novy–MacNeal–Nicolle (NNN) media and checked for promastigotes twice a week for 6 weeks. Leishmania promastigotes after mass production in RPMI 1640 media were identified by Nested-PCR assay.

Moreover, DNA was extracted from the prepared smear and Phenol- chloroform- Isoemil alcohol extraction method was used to extract DNAs according to Sambrook method (24).

The DNA samples were dissolved in 50 µl deionized distilled water and stored at 4° C (25). Specific primers related to variable regions of KDNA were used with External primers C1SB1XR (CCGAGTAGCAGAAACTCCCGTTGA) and CSB2XF (ATTTTTCGCGA TTTTCG CAGAACG) in the first-round PCR and internal primers LiR (TCGCAGGAA CGCAGAACG) and 13Z (ACTGGGGG TTGGTGTAAAATAG) in the second round were applied (26). PCR products of second –round of the PCR were loaded onto a 1.5% agarose gel and the results were compared with standard band markers of L. tropica, 750 bp and L. infantum, 680 bp.

Ethical approval

This study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committees of Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Iran. As well as it was reviewed and approved by the Kerman University of Medical Sciences as a joint research project.

Data analysis

Chi-square and Fisher exact tests were used to compare sero-prevalence values relative to gender, age, and clinical signs. Analyses were conducted using SPSS 16 (SPSS Inc. Headquarters USA) software with confidence interval of 0.95.

Results

Serological survey

Of the 1476 prepared plasma samples, 1374 (93.1 %) were collected from children ≤12 years old and 102 samples (6.9%) were from adults. Altogether, 758(51.3%) out of 1476 of the studied population were male and 718 (48.7%) were female (Table 1). Thirty-seven of the blood samples (2.5%) showed anti-Leishmania antibodies at titers ≥1:800 and only 14 (0.95%) showed anti-Leishmania antibodies at titers ≥1:3200 (Table 1). No statistically significant differences between human Leishmania infection (≥ 1:3200) and gender, were observed (P=0.330).

Table 1.

Sero-prevalence of human visceral Leishmania infection by gender in Baft district, southeast of Iran (2009–2010)

| Gender | No. examined | Anti-Leishmania antibody titers | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1:800, 1:1600 | ≤1:3200 | ||||||

| No. | Prevalence (%) | No. | Prevalence (%) | No. | Prevalence (%) | ||

| Male | 758 | 10 | 1.3 | 9 | 1.2 | 19 | 2.5 |

| Female | 718 | 13 | 1.8 | 5 | 0.7 | 18 | 2.5 |

| Total | 1476 | 23 | 1.55 | 14 | 0.95 | 37 | 2.5 |

No statistically significant differences between human Leishmania infection (at titers ≥1:3200) and gender were observed

The highest proportion of sero-positivity was in children 5–8 years of age and the rate of the infection was decreased with the increasing of the age (Table 2). Anti-Leishmania antibodies were detected in only three >12 years old at titers 1:800 and higher. Two sero-positive children were found with previous history of kala-azar.

Table 2.

Sero-prevalence of human visceral Leishmania infection by age group in Baft district, southeast of Iran (2009–2010)

| Age groups (years) | No. examined | Anti-Leishmania antibody titers | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤1:3200 | ≥1:3200 | ||||||

| No. | Sero-prevalence (%) | No. | Sero-prevalence (%) | No. | Sero-prevalence (%) | ||

| < 0-4 | 447 | 7 | 1.56 | 4 | 0.9 | 11 | 2.46 |

| 5-8 | 495 | 9 | 1.81 | 7 | 1.41 | 16 | 3.22 |

| 9-12 | 432 | 5 | 1.15 | 2 | 0.47 | 7 | 1.62 |

| >12 | 102 | 2 | 1.96 | 1 | 0.98 | 3 | 2.94 |

| Total | 1476 | 23 | 1.55 | 14 | 0.95 | 37 | 2.5 |

No statistically significant differences between human Leishmania infection (at titers ≥1:3200) and age groups (≤ 12 and >12 year ages) were observed

Thirteen cases (0.95%) from the 1374 samples were from children ≤12 years old showed anti-Leishmania antibodies at the titers ≥1:3200 while only one of adult (>12 years old) showed this titer of anti- leishmania antibodies. In this study, six VL cases with clinical signs and symptoms including fever (5), splenomegaly (3) and anemia (4), were found.

VL cases were more frequent in rural areas and most sero-positive cases were found among Sarnei (3 cases), Dehsard (2 cases), Khosroabad (2 cases), Torang (2 cases), and Goshk (2 cases) villages from southern Baft district.

Altogether, seven of the 30 domestic dogs (23.3%) showed anti-Leishmania antibodies at titers of 1:320 and higher. Other characteristics of the studied dogs were summarized in Table 3 and 4.

Table 3.

Sero-prevalence of Leishmania infection by age group in domestic dogs in Baft district, southeast of Iran (2009–2010)

| Age groups (years) | No. examined (%) | DAT positivity (≥1:320) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Prevalence (%) | ||

| < 0-3 | 15 (50) | 3 | 26.6 |

| 4-7 | 10 (33.4) | 2 | 20 |

| ≤8 | 5 (16.6) | 1 | 40 |

| Total | 30(100) | 7 | 23.3 |

No statistically significant differences between canine Leishmania infection (at titers ≥1:320) and age groups (≤ 8 and >8 year ages) were found

Table 4.

Sero-prevalence of Leishmania infection by gender in domestic dogs in Baft district, southeast of Iran (2009-2010)

| Gender | No. examined (%) | DAT positivity ( ≥1:320) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Prevalence (%) | ||

| Male | 21 (70) | 5 | 23.8 |

| Female | 9 (30) | 2 | 22.2 |

| Total | 30(100) | 7 | 23.3 |

No statistically significant differences between canine Leishmania infection (and gender were found

Parasitological examination

In parasitology examinations, amastigotes were found in the smears prepared from the spleen of five dogs out of the 7 sero-positive dogs in the Dehsard, Khosroabad, Torang and Goshk villages.

Pathological study

Samples prepared from spleen of 5 out of 7 sero-positive dogs showed pathological changes including: hyperplasia of macrophage with amastigotes (Leishman bodies) within them and inflammatory cells that occupied sinusoids and splenic cords.

Molecular characterization

All the five Leishmania isolated from infected dogs were identified as L. infantum (680 bp) by nested-PCR assay (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Gel electrophoresis of PCR products in isolates related to a sero-positive dog in Baft district (2009–2010); A: Marker- 100 bp, B: L. tropica-750 bp, C. (Leishmania infantum standard=680 bp), D: sample, E, F: Negative Control.

Discussion

Visceral leishmaniasis (VL) is the most severe form of leishmaniasis (3, 4). It is the highly lethal parasitic diseases in the world, responsible for an estimated 500,000 cases each year, worldwide. Visceral leishmaniasis is endemic in some parts of Iran including Ardabil, Fars, East Azerbaijan, Bushehr and northern Khorasan provinces (5–13) and sporadic form of the disease occurred in other parts of the country (13).

In recent years, 108 cases of VL have been reported in Kerman Province. All cases have been referred from health houses and health clinics to pediatrics wards of Afzalipour Medical Center at Kerman University of Medical Sciences. Approximately half of these cases were from Baft district (14, 15). Since, no sero-epidemiological study had not been performed in last decade in Baft, this study was conducted to evaluate the epidemiological aspects of visceral leishm-aniasis in this area.

DAT was used in this study for detection of L. infantum infection in human and dogs because for its highly specificity and sensitivity.

Of the 1476 samples, 14 cases (0.95%) of human samples showed specific anti-Leishmania antibodies with titers ≥1:3200 and 23 individuals (1.55%) showed titers between 1:800 and 1:1600 by DAT. About 2.46% of sero-positive cases were detected in children of under 5 years old and 3.22% in children of between5–8 years ages. However, from 3 sero-positive cases with high titers of anti-Leishmania antibodies (≥1:3200) 2 were children in the age group 8-12 years old and only one of them was ≥12 years age.

A sero-epidemiological study was carried out by Mohebali et al. on 12144 human serum samples collected from four geographical zones of Iran; 168 (2.6%) of the samples were positive 93.6% of the VL infection were from children of under 5 years of age and only 6.4% of them were older than 5 years old (13). In endemic areas of Ardabil and Fars provinces more than 90% of patients were children up to 12 years old (6). In Qom province, majority of the cases were among children of 7–10 years of age (9). In northern Khorassan Province, almost 70% of the sero-positive cases were under 12 years and only one of infected individual had higher than 12 years age (11).

In our study 1.2% of the sero-positive cases (≥1:3200) were male and 0.7% female; No significant difference between male and female was seen. According to a study, no significant difference was observed in incidence rate of VL between males and females before puberty but after puberty, the incidence rate was significantly higher in males (30). In previous studies conducted in Iran there has been no agreement in consistency of the data between males and females (9, 13). These differences seem to be associated with method of sampling, number of population and the presence or absence of clinical symptoms.

In the current study, we found Leishmania infection in seven domestic dogs (23%) that showed anti-Leishmania antibodies with titers ≥1:320. Based on two studies designed for CVL sero-prevalence of canine visceral leishmaniasis in Iran, sero-positivity rate was achieved 21.6% and 14.2%, respectively (27, 28).

In this study, no statistically significant difference between canine Leishmania infections concerning the gender was found. Similar results were found by Bokai et al. and Mohebali et al. in 2005 (28, 29). In this survey, Leishmania species isolated from the spleen of five sero-positive dogs was identified as L. infantum by Nested-PCR method and domestic dogs (Canis familiaris) were had potential role in transmission of the parasites to human particularly children.

In addition, six VL patients were diagnosed that all of them were DAT -positive (titers ≥1:3200). Fever (83%), anemia (66%) and splenomegaly (50%) were the predominant signs and symptoms. These findings were the same clinical manifestations that reported by other investigators (6, 11, 13, 31, 32).

In conclusion, it seems that visceral leishmaniasis is endemic in southern villages of Baft district, southeast of Iran. To control VL in this area, we suggest the elimination of stray dogs, identifying suspected human cases and ownership dogs by periodic DAT and treatment of infected cases. Early detection and treatment of visceral leishmaniasis can reduce the incidence of severe illness and death. It is important for clinicians to change their perceptions of the population at risk.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by Teheran University of Medical Sciences (Research No: 88-03-27-9223) and Kerman University of Medical Sciences, Iran. We thank Dr. Dabiri for help in performance of Pathological examinations at Dept. of Pathology, Kerman University of Medical Sciences, Mr. Vahid jahanbakhsh for the performance of data analysis, Najmeh Soltani and the other staff of the District Health Centers in Baft, especially Shahmaran, Dehsard, Khosroabad, Torang and Sarnei. In addition, the authors thanks from Mrs.Soroor Charehdar for helps in providing laboratory facilities for preparation of DAT antigens in the School of Public Health, Tehran University of Medical Sciences. The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

References

- 1.Schmidt G, Roberts LS. Foundation of parasitology fourth edition. 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 2.James William D, Berger Timothy G. Diseases of the Skin: clinical dermatology. Saunders Elsevier. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Desjeux P. The increase of risk factors for leishmaniasis worldwide. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2001;95(3):239–243. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(01)90223-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization. The leishmaniases, Report of WHO Expert committee; Geneva: World Health Organizatiom; 1990. p. 793. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Edrissian GhH, Nadim A, Alborzi A, Ardehali S. Visceral leishmaniasis. The Iranian Experience. Arch Iranian Med. 1998;1(1):22–26. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Edrissian GhH, Ahanchin H, Gharachani AR, Ghorbani M, Nadim A, Ardehali S. Seroepidemiological studies of visceral leishmaniasis and search for animal reservoir in Fars province. J Iranian Med Sci. 1993;18:99–105. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Edrissian GhH, Hajjaran H, Mohebali M, Soleimanzadeh G, Bokaei S. Application and evaluation of direct agglutination test in ser-diagnosis of visceral leishmaniasis in man and canine reservoirs in Iran. Iranian J Med Sci. 1996;21:119–124. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mohebali M, Hamzavi Y, Edrissian GhH, Forouzani A. Seroepidemiological studies of visceral leishmaniasis in Bushehr province, south of IR of Iran. East Mediterr Health J. 2001;7:912–917. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fakhar M, Mohebali M, Barani M. Identification of Endemic focus of kala-azar and seroepidemiological study of visceral Leishmania infection in human and canine in Qom province, Iran. Armaghane Danesh (in Persian) 2004;9(33):43–52. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moshfe A, Mohebali M, Edrissian GhH, Hajjaran H, Akhoundi B, Zarei Z. Seroepidemiological study on canine visceral Leishmaniasis in Meshkin-Shahr district, Ardabil province, northwest of Iran during 2006–2007. Iranian J Parasitol. 2008;3(3):1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Torabi V, Mohebli M, Edrissian GhH, Keshavarz H, Hajjaran H, Akhoundi B, Mohajeri M, Zarei Z, Sanati A, Delshad A. Seroepidemiological study of visceral leishmaniasis (kala-azar) by direct agglutination in Bojnoord district, northern Khorasan province. Iranian J Epidemiol. 2008;4(3, 4):43–50. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Edrissian GhH, Hafizi A, Afshar A, Soleiman–zadeh G, Movahed-Danesh AM, Garoussi Z. An endemic focus of visceral leishmaniasis in Meshkin-Shahr, east Azerbaijan province, north-west part of Iran and IFA serological survey of the disease in this area. Bull Soc Pathol Exot. 1988;81(2):238–248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mohebali M, Edrissian GhH, Nadim A, Hajjaran H, Akhoundi B, Hooshmand B, Zarei Z, Arshi Sh, Mirsamadi N, Manouchehri Naeini K, Mamishi S, Sanati AA, Moshfe AA, Charehdar S, Fakhar M. Application of direct agglutination test (DAT) for the diagnosis and seroepidemiological studies of visceral leishmaniasis in Iran. Iranian J Parasitol. 2006;1(1):15–25. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Niknafs P, Daie Parizi M, Ahmadi A. Report of 40 cases of kala-azar from Kerman province. J Kerman Univ Med Sci. 1994;1:30–37. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barati M, Daie Parizi M, Sharifi I. Epidemiological and Clinical aspects of kala-azar in hospitalized children of Kerman province, during 1991–2006. J Kerman Univ Med Sci. 2008;15(2):148–155. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Keshavarz H, Zangiabadi M, Mamishi S. Serological study on visceral leishm-aniasis (kala-azar) in children under 12 years in Baft district by IFAT, 1994; 1997. p. 88. 7th National congress of parasitic disease in Iran. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sharifi I, Daneshvar H. The prevalence of visceral leishmaniasis in suspected canine reservoirs in southeastern Iran. Iranian J Basic Med Sci. 1996;21:130–134. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aghaie Afshar A, Rasi Y, Ebaie MR, Aghaie Afshar M. Determination of fauna and monthly activity of sandflies in the south of Baft district, Kerman province in 2004. J Kerman Univ Med Sci. 2004;12(2):136–141. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hailu A. Pre- and post-treatment antibody levels in visceral leishmaniasis. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1990;84(5):673–675. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(90)90141-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schallig HDFH, Schoone GJ, Kroon CCM, Hailu A, Chappuis F, Veeken H. Development and application of simple’ diagnostic tools for visceral leishmaniasis. Med Microbiol Immunol. 2001;190:69–71. doi: 10.1007/s004300100083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ozbel Y, Oskam L, Ozensoy S, Turgay N, Alkan MZ, Jaffe CL, Ozcel MA. A survey on canine leishmaniasis in western Turkey by parasite. Acta Trop. 2000;74:1–6. doi: 10.1016/s0001-706x(99)00047-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harith AE, Kolk AHJ, Leeuwenburg J, et al. Improvement of direct agglutination test for field studies of visceral leishmaniasis. J Clin Microbiol. 1988;26(7):1321–1325. doi: 10.1128/jcm.26.7.1321-1325.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harith A, Salappendel RJ, Reiter I, Knapen F, Korte P, Huigen E, Kolk RHG. Application of a direct agglutination test for detection of specific anti-Leishmania antibodies in the canine reservoir. J Clin Microbiol. 1989;27:2252–2257. doi: 10.1128/jcm.27.10.2252-2257.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sambrook J, Russel DW. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 3rd Ed. New York: CHSL press; 2001. Chapter 8. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Karamian M. A survey PCR utilization special primer in cutaneous leishmaniasis diagnosis and Leishmania species; Shiraz Univ Med Sci; 2001. pp. 69–90. (Msc. Thesis) [Google Scholar]

- 26.Noyes HA, Belli AA, Maingon R. Appraisal of various random amplified polymorphic DNA-polymerase chain reaction primers for Leishmania identification. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1996;55(1):98–104. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1996.55.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gavgani AS, Mohite H, Edrissian GH, Mohebali M, Davies CR. Domestic dog ownership in Iran is a risk factor for human infection with Leishmania infantum . Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2002;67(5):511–515. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2002.67.511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mohebali M, Hajjaran H, Hamzavi Y, Mobedi I, Arshi S, Zarei Z, Akhoundi B, Manouchehri Naeini K, Avizeh R, Fakhar M. Epidemiological aspects of canine visceral leishmaniosis in the Islamic Republic of Iran. Vet Parasitol. 2005;129(3–4):243–251. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2005.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bokai S, Mobedi I, Edrissian Gh.H, Nadim A. Seroepidemiological study of canine visceral leishmaniasis in Meshkin-Shahr, northwest of Iran. Arch Inst Razi. 1998;48–49:41–6. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sharma MC, Gupta AK, Saran R, Sinha SP. The effect of age and sex on incidence of kala-azar. The Journal of Communicable Diseases. 1990;22:277–278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Soleimanzadeh G, Edrissian GHH, Movahhed-Danesh AM, Nadim A. Epidemiological aspects of kala-azar in Meshkin-Shahr, Iran: human infection. Bull World Health Org. 1993;71(6):759–762. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mohebali M, Edrissian GhH, Shirzadi MR, Akhoundi B, Hajjaran H, Zarei Z, Molaei S, Iraj Sharifi, Setareh Mamishi, Hossein Mahmoudvand, Vahid Torabi, Abdolali Moshfe AA, Malmasi AA, Motazedian MH. An observational study for current distribution of visceral leishm-aniasis in different geographical zones of Iran for implication of health policy. Travel Med Inf Dis. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2011.02.003. in Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]