Abstract

A 5-month old puppy with muco-cutaneous lesions in the chin, around lips and eyes was examined physically and microscopically for leishmaniasis. Muco-cutaneous lesions containing a large number of amastigotes of Leishmania spp. were observed. Amastigotes were also detected in liver and spleen of the puppy. The animal was positive with Dipstick rK39 kit and high level of anti-Leishmania antibodies was detected by direct agglutination test (DAT). DNA, Using PCR-RFLP technique extracted from cultured Leishmania promastigotes and L. tropica was identified. This is the first report of concurrent mucosal and visceral involvement of L. tropica in a puppy from Iran.

Keywords: Disseminated leishmaniasis, Leishmania tropic, Dog, Iran

Introduction

Leishmaniasis is an infectious disease caused by various species of Leishmania parasites involving domestic and wild canines and humans. Visceral leishmaniasis (VL) is endemic in the Mediterranean basin including Iran (1–3).Domestic dogs (Canis familiaris) are the main reservoir hosts for Mediterranean type of visceral leishmaniasis (1).

Canine and Human VL are endemic in northwest and southern parts of Iran, with L. infantum as the main causative agent (4, 5). L. tropica is the principal agent of urban cutaneous leishmaniasis in Iran (6).

Leishmania tropica has been isolated from a few cases of human and canine VL in Africa and some parts of Middle East including Iran (3, 4, 7–9).

Case report

A 5-month old male mixed breed dog with several weeks’ history of muco-cutaneous lesions in the chin, around lips and eyes (Fig.1) from Karaj, central Iran, was referred to Small Animal Hospital, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, University of Tehran. It seemed the animal had borne and raised in Karaj as the owner had purchased him a few days ago from a breeder in this area.

Fig. 1.

Skin lesions in the chin and mucocutaneous junction of the lips

Clinical examinations showed generalized lymphadenopathy and various muco-cutaneous lesions including macules, papules, plaques, and nodules in the chin, mucocutaneous junction of the lips and around eyelids (Fig.1).The animal had no systemic signs such as weight loss, emaciation and other systemic clinical signs.

The blood sample was taken from the infected dog and centrifuged at 1000×g for 5–10 min and its serum was separated and tested for anti-Leishmania antibodies using Dipstick rK39 (10,11) and direct agglutination test (DAT) (11,12).

Several impression smears were taken from the lesions for parasitological examination. After finding high DAT titers of anti-Leishmania antibodies, the animal was dissected and a few thin smears were prepared from its spleen and liver. All prepared smears were fixed by methanol, stained with 10% Giemsa, and examined microscopically for the presence of amastigote forms of Leishmania spp.

Biopsy specimens were collected aseptically from spleen and liver and then cultured into biphasic (NNN) and monophasic culture media (RPMI 1640, Gibco, Karlsruhe, Germany). The inoculation cultures were incubated at 21°C and promastigotes were seen at least one-week post cultivation.

DNA, using FlexiGen DNA kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany), extracted from Leishmania promastigotes grown for at least one week in RPMI 1640 media (Gibco, Karlsruhe, Germany) and isolated originally from spleen and liver of the dog. Identification of Leishmania species was based on PCR-RFLP technique using nagt gene and ACC1 enzyme. The results were compared with standard species of L.infantum (MCAN/IR/96/LON49),L.tropica,(MHOM/IR/99/YAZ1) and L.major (MRHO/IR/75/ER) using 2 primers including L1 as forward (TCATGACTCTTGGCCTGGTAG) and L4 as reverse (CTCTAGCG-CACTTCATCGTAG) in the School of Public Health, Tehran University of Medical Sciences. The PCR products sent for sequence analysis (Hope Generation Foundation, Tehran, Iran; www.hopegen.org).

Hemogram of the animal was normal. Generalized and especially sub-mandibular lymphadenitis was the only abnormal finding at necropsy. The sizes of spleen and liver appeared normal.

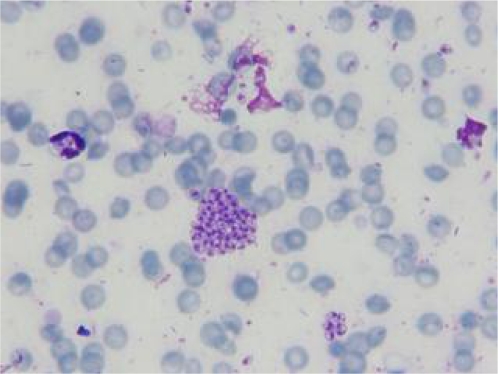

Anti-Leishmania antibodies using the cut-off value of 1:320 were detected at 1: 20480 by DAT. The result of Dipstick rk39 was also positive. A great number of amastigotes were observed in the cytoplasm of macrophages derived from mucosal lesions while scanty amastigotes of Leishmania were seen in the visceral macrophages (Fig. 2).The species of this isolate was identified as L. tropica by PCR-RFLP technique. The nucleotide sequence data were submitted to the GenBank database and registered with accession numbers HM234011 and HM234012 for both L. tropica isolated from mucosal and visceral involvement, respectively. These Leishmania isolates showed 99% homology with together.

Fig. 2.

Macrophages containing amastigotes of L. tropica isolated from liver and spleen of the infected puppy (Giemsa stain, X1000)

Discussion

Leishmania tropica is the main causative organism of urban cutaneous leishmaniasis in Iran (13) and it has been recently isolated from a few cases of CVL and HVL in Africa and some parts of Middle East including Iran (2,3,7,9). In 1992, L. tropica has caused HVL in American soldiers returning from Persian Gulf (1,8). Mohebali et al.(2005) described VL with isolation of L. tropica in a domestic dog without any cutaneous involvement (4). In the present report, L. tropica has been isolated concurrently from mucosal and visceral lesions of a puppy which confirms that L. tropica is not only able to induce cutaneous lesions but also potentially able to be disseminated into viscera of dogs.

In contrast to cutaneous leishmaniasis, which antibody response is low or absent, detection of high antibody titers is expected in visceral leishmaniasis caused by L. tropica (8). DAT titer in the present case was 1:20480 which looks very high and in agreement with the findings of Hajjaran et al. (2007) who observed the same titer in an 8-year old dog infected with visceral leishmaniasis caused by L. tropica (3).

CVL is usually a chronic disease and clinical signs depending on virulence of protozoan species and genetic susceptibility of the host may appear 3 months to 7 years post infection (1). This disease mainly observed in adults (1-3 years) or old dogs (8-10 years) and its report in juveniles, is quite rare (14). CVL has been mostly prevalent in dogs of 8-years or even older and less prevalent in dogs younger than 3-years in Iran (4). The isolation of L. tropica from visceral organs of a 5-month old puppy with high DAT titer is for the first time to be reported, however despite cutaneous lesions in this case, as there was no systemic clinical signs suggestive of CVL, until finding more clinical evidences and clues we assume it as disseminated leishmaniasis caused by L. tropica rather than classic visceral leishmaniasis. The frequency rate of canine visceral leishmaniasis caused by L. tropica and role of infected dogs as the sources for human infection, need further studies.

Acknowledgements

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests.

References

- 1.Baneth G. Missouri; Saunders Elsevier. 2006. Leishmaniases; pp. 685–698. Greene CE, Infectious Diseases of the Dog and Cat. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mohebali M, Edrissian GhH, Nadim A, Hajjaran H, Akhoundi B, Hooshmand B, Zarei Z, Arshi Sh, Mirsamadi N, Man-ouchehri Naeini K, Mamishi S, Sanati AA, Moshfe AA, Charehdar S, Fakhar M. Application of Direct Agg-lutination Test (DAT) for the Diagnosis and Seroepidemiological Studies of Visceral leishmaniasis in Iran. Iranian J Parasitol. 2006;1(1):15–25. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hajjaran H, Mohebali M, Zarei Z, Edrissian GH. Leishmania tropica: Another Etiological Agent of Canine Visceral leishmaniasis in Iran. Iranian J Publ Health. 2007;36:85–88. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mohebali M, Hajjaran H, Hamzavi Y, Mobedi I, et al. Epidemiological aspects of canine visceral leishmaniasis in the Islamic Republic of Iran. Vet Parasitol. 2005;129:243–251. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2005.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Akhoundi B, Mohebali M, Babakhan L, Edrissian GhH, Eslami MB, Keshavarz H, Malekafzali H. Rapid detection of human Leishmania infantum infection: A comparative field study using the fast agglutination screening test and the direct agglutination test. Travel Med Inf Dis. 2010;8:305–310. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2010.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yaghoobi-Ershadi MR, Hanafi-Bojd AA, Javadian E, Jafari R. A new focus of cutaneous leishmaniasis caused by Leishmania tropica . Saudi Med J. 2002;23:291–294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lemrani M, Nejjar R, Pratlong F. A new Leishmania tropica zymodeme—causative agent of canine visceral leishmaniasis in northern Morocco. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2002;96(6):637–638. doi: 10.1179/000349802125001645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stratton CW. Visceral leishmaniasis Caused by Leishmania tropica in American military personnel deployed to Southwest Asia during Operation Desert Storm. Infect Dis Newsletter. 1992;11:9–12. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jafari S, Hajiabdolbaghi M, Mohebali M, Hajjaran H, Hashemian H. Disseminated leishmaniasis caused by Leishmania tropica in HIV-positive patients in the Islamic Republic of Iran. Eastern Mediterr Health J. 2010;16(3):340–343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Edrissian GH, Shamssi S, Mohebali M, Hajjaran H, Mamishi S, Desjeux P. Evaluation of rapid “Dipstick RK39” test in diagnosis and serological survey of visceral Leishmaniasis in humans and dogs in Iran. Arch Iranian Med. 2003;6(1):29–31. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mohebali M, Taran M, Zareii Z. Rapid detection of Leishmania infantum infection in dogs: Comparative study using immunochromatographic dipstick rK39 test and direct agglutination. Vet Parasitol. 2004;121:139–145. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2004.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harith A, Salappendel RJ, Reiter I, Knapen F, et al. Application of a direct agglutination test for detection of specific anti-Leishmania antibodies in the canine reservoir. J Clin Microbiol. 1989;27:2252–2257. doi: 10.1128/jcm.27.10.2252-2257.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nadim A, Javadian E, Mohebali M, Momeni A. Leishmania parasites and leishmaniasis. 3rd. Edition. Nashre Daneshgahi Press (in persian); 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Santos M, Marcos R, Assunção M, Matos AJF. Polyarthritis associated with visceral leishmaniasis in a juvenile dog. Vet Parasitol. 2006;141:340–344. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2006.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]